Introduction

Globally, the prevalence, severity and complexity of mental health issues among students in higher education institutions (HEIs) have increased in the last decade (Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Lattie and Eisenberg2019). HEIs are struggling to meet growing demands for mental health services (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Carney, Youn, Janis, Castonguay, Hayes and Locke2017; Fox et al., Reference Fox, Byrne, Surdey, Team, Woods and O'Donovan2020). A World Health Organisation (WHO) report found that 35% of first year university students screened positive for at least one psychological disorder, with anxiety and depression the most common conditions reported (Auerbach et al., Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet and Cuijpers2018). Anxiety and depression are often associated with suicidality and self-harm, which are also prevalent in university students (Mortier et al., Reference Mortier, Cuijpers, Kiekens, Auerbach, Demyttenaere and Green2018).

Although higher education can offer opportunities for growth and maturation, it can expose individuals to stressors including living away from home, managing increased social and financial independence, balancing work/family/student responsibilities, experimenting with drugs/alcohol/sexual behaviours and experiencing pressures to succeed in competitive job markets (Bewick et al., Reference Bewick, Koutsopouloub, Miles, Slaad and Barkham2010; Cleary et al., Reference Cleary, Walter and Jackson2011; Auerbach et al., Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet and Cuijpers2018). It is therefore unsurprising that third-level students generally demonstrate higher levels of psychological distress compared to non-university age-matched peers (Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Keane, Houghton and Dunne2010; Karwig et al., Reference Karwig, Chambers and Murphy2015; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Bira, Gastelum, Weiss and Vanderford2018). This is problematic, not only because of the adverse psychological and socioemotional outcomes associated with mental ill health, but also the negative influence that poor mental health has on course completion and academic performance (Collins & Mowbray, Reference Collins and Mowbray2005; Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Lattie and Eisenberg2019).

HEIs may be well placed to address students’ mental health concerns as they constitute single settings that integrate many important aspects of students’ lives including academic and social life, health/support services and residences (Hunt & Eisenberg, Reference Hunt and Eisenberg2010). Efforts to promote student mental health need to be guided by robust and comprehensive data on risk and protective factors across various student cohorts (Orygen, 2017).

Established risk factors for poorer student mental health include being female (Bayram & Bilgel, Reference Bayram and Bilgel2008), younger (first year undergraduate student; Dyson & Renk, Reference Dyson and Renk2006), an international student (Hefner & Eisenberg, Reference Hefner and Eisenberg2009), socioeconomically disadvantaged (Stallman, Reference Stallman2010), having a disability/mental health difficulty (Association for Higher Education and Disability [AHEAD], 2018) and belonging to a sexual or gender minority (Smithies & Byrom, Reference Smithies and Byrom2018; Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, McGuire, Busby, Eisenberg, Zheng and Pistorello2020b). Alcohol and drug use (Lanier et al., Reference Lanier, Nicholson and Duncan2001) and risky sexual behaviours (e.g., unprotected sex) are also associated with poorer mental health outcomes in students. Peer risks include experiencing non-consensual touching/sex (Pinsky et al., Reference Pinsky, Shepard, Bird, Gilmore, Norris and Davis2017), while family risks include having a parent with a mental health difficulty and/or addiction (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Brewer and Rankin2012).

Less research has focused on protective factors among students, which are assets that can support an individual’s capacity to successfully respond to life’s stresses (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Pereira and Relvas2015). However, resilience (Hartley, Reference Hartley2013), optimism (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Mergler and Boman2014), life satisfaction (Renshaw & Cohen, Reference Renshaw and Cohen2014), self-esteem (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Liu, Hua, Lv, Wang and Yan2010), social support (Hefner & Eisenberg, Reference Hefner and Eisenberg2009), low avoidance coping and high problem-focused coping (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Liu, Hua, Lv, Wang and Yan2010) have been identified as protective factors in third-level students. Help-seeking behaviour is another protective factor, yet many students fail to disclose disabilities/mental health difficulties, and as many as half of students fail to seek help for their mental health concerns (Thorley, Reference Thorley2017). Therefore, identifying ways to enhance protective factors for mental health is important for directing preventative action in the area of student mental health (Shortt & Spence, Reference Shortt and Spence2006).

While many risk/protective factors have been identified, little research has investigated how these factors profile across different student cohorts. Given the diversification of the student profile in recent years due to national policies endorsing equity of access to higher education, and the putative role of diversification in the growth of student mental health issues (Said et al., Reference Said, Kypri and Bowman2013; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Farrelly, Clarke and Cannon2020), it is important to document mental health across cohorts, so that service provision can accurately address students’ mental health needs and target more “at risk” groups (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Byrne, Surdey, Team, Woods and O'Donovan2020).

There is an emerging body of research examining differences in mental health, risk and protective factors across student cohorts, including undergraduates, postgraduates, “at risk” student groups and students attending varying institution types. There is some evidence to suggest that postgraduate taught (PGT) and postgraduate research (PGR) students exhibit greater help-seeking behaviours than undergraduates, but they are less likely to disclose mental health difficulties. Postgraduates also experience particular stressors such as poor work-life balance, unsupportive relationships with supervisors and high workload/expectations, but their ability to cope with stressors tends to exceed that of undergraduates (Wyatt & Oswalt, Reference Wyatt and Oswalt2013; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Bira, Gastelum, Weiss and Vanderford2018). A finding by the Higher Education Authority (HEA, 2015), suggests that in Ireland, students on access routes that facilitate admission to higher education among students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds (Higher Education Access Route; HEAR) and students whose disabilities have impacted their second-level education (Disability Access Route to Education; DARE) are at increased risk of mental health difficulties. Additionally, mature students, defined by the HEA as students aged 23 years and above, are a cohort that may face additional pressures of managing their studies alongside family/caregiver responsibilities and finances (Tones et al., Reference Tones, Fraser, Elder and White2009). Furthermore, there is evidence internationally that students in community colleges report more severe psychological concerns than traditional university students (Katz & Davison, Reference Katz and Davison2014). Therefore, it is worth investigating whether there are differences in risk and protective factors for mental health between the two main third-level institution types in Ireland – universities and Institutes of Technology (IoTs) – which differ in educational aims, student profiles, size, culture, resources, strategic priorities, models of care and supports for student mental health (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Sheils, Carroll, Frawley, Patterson and Pigott2020; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Farrelly, Clarke and Cannon2020).

The literature cites an emerging “crisis” in student mental health and the extent of mental health problems in undergraduates versus postgraduates is widely contested (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Bira, Gastelum, Weiss and Vanderford2018), yet there are little robust data to inform these debates (Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Wilson and Levecque2018). Current studies also fail to incorporate a wide range of risk/protective factors together in a single study and provide a less comprehensive understanding of the range of factors involved in mental health (Shortt & Spence, Reference Shortt and Spence2006). Finally, data on student mental health in Irish universities and IoTs are limited (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Farrelly, Clarke and Cannon2020) and little is known about the risk/protective factors for mental health relevant to potentially vulnerable student cohorts including HEAR, DARE or mature students.

This study sought to address these gaps by profiling a wide range of risk and protective factors for mental health across degree type (undergraduate, PGT, PGR), access route (HEAR, DARE, mature, traditional entry) and institution type (universities, IoTs) in a large sample of third-level students in Ireland.

Method

Sample

This was a convenience sample of 9935 students aged 18–65+ years, drawn from the post-second level subset of the national cross-sectional study My World Survey 2 (MWS2-PSL). Data from the MWS-PSL were collected from 12 third-level institutions across Ireland, including 5 out of 14 IoTs (37.5%) and 7 out of 7 universities (100%).Footnote 1

Procedure

On receiving ethical approval from the researcher’s host institution, Registrars (or equivalent) of all third-level institutions were contacted about the research. If the Registrar was agreeable to the study, a designated member of staff within the institution was appointed to send an email to all registered students informing them of the study and inviting them to participate. The email contained a weblink to the information sheet, consent form and survey, which was administered using Qualtrics software. Participants were required to provide consent before proceeding to the survey and were debriefed and thanked on completion.

Measures

College and socio-demographic factors

Participants were asked to indicate their institution status (university or IoT), degree type (undergraduate, PGT or PGR) and access route (HEAR, DARE, traditional entry or mature). Participants were also asked to provide their gender, age, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Mental health

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995) measures the frequency and severity of participants' experiences of negative emotions in the past week. The depression and anxiety subscales of the DASS were used. Frequency ratings are made on a 4-point Likert scale. Recommended cut-off scores classify participants as displaying low, mild, moderate, severe or very severe levels of depression and anxiety. The DASS has consistently been found to be reliable and valid (Crawford & Henry, Reference Crawford and Henry2003; Tully et al., Reference Tully, Zajac and Venning2009).

Suicidality was measured using three items (see supplementary materials), that assessed whether participants had ever had thoughts that life was not worth living, engaged in self-harm or had made a suicide attempt.

Risk factors

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fuente and Grant1993) is an 11-item scale that screens for hazardous alcohol consumption. Responses are indicated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never” to 4 “almost daily”. Recommended cut-off scores classify alcohol behaviour as low-risk drinking (<8), problem drinking (8–15), harmful/hazardous drinking (16–19) or possible alcohol dependence (≤20). The reliability and validity of the AUDIT has been demonstrated in numerous studies (Reinert & Allen, Reference Reinert and Allen2002).

The Drug Abuse Screen Test (DAST-10; Skinner, Reference Skinner1982) assesses drug use in the past 12 months. Items require a “yes/no” response. Recommended cut-offs are (0) no problems, (1–2) low-level problems, (3–10) moderate/severe problems. The DAST has moderate to high levels of validity, sensitivity and specificity (Yudko et al., Reference Yudko, Lozhkina and Fouts2007).

Additional risk items

A series of single-item questions assessed risk, including top stressors, cannabis use, sexual coercion, risky sexual behaviours, numbers of days absent from college/university in the last month, presence of a long-term mental and/or physical health difficulty and parent mental health/addiction status (see supplementary materials).

Protective factors

The Adapted Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI-15; Amirkhan, Reference Amirkhan1990) assesses dimensions of coping strategies using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “never” to 6 “always”. Two subscales, problem-focused (regarded as a positive method of coping) and avoidance coping (regarded as a negative method), were used. The CSI shows good test–retest reliability and construct validity (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Bormann, Cropanzano and James1995).

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Dalen, Wiggins, Tooley, Christopher and Bernard2008) is a 6-item scale that measures resilience. Responses are indicated on a scale of 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicate greater resilience. A methodological review of resilience measures rated the BRS as having one of the best psychometric ratings (Windle et al., Reference Windle, Bennett and Noyes2011).

The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-r; Scheier et al., Reference Scheier, Carver and Bridges1994) measures dispositional optimism using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. The LOT-r demonstrates good test–retest reliability (Carver & Gaines, Reference Carver and Gaines1987).

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965) assesses self-evaluations of worthiness using 4-point Likert scales ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree” Studies have found the RSE to demonstrate strong psychometric properties (Schmitt & Allik, Reference Schmitt and Allik2005).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985) measures global cognitive judgements of one’s life using a 7-point Likert scale where responses range from 1 "very strongly disagree" to 7 “very strongly agree”. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction. The five-item scale demonstrates good psychometric properties (Arrindell et al., Reference Arrindell, Heesink and Feij1999; Di Fabio & Gori, Reference Di Fabio and Gori2016).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988) is a 12-item scale that assesses perceived social support from family, friends and a significant other. Responses are given on a seven-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater levels of support. The scale’s construct validity has been supported and internal consistency and test–retest reliability are considered good (Zimet et al., Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988).

Additional protective items

Several single-item questions assessed protective variables including help-seeking (intentions and behaviours), disclosure of mental health difficulty to college disability services, receipt of college educational supports, perceived coping capacity and presence of a supportive adult (see supplementary materials).

Statistical analysis

Separate student mental health profiles were produced for 1. Degree status (UG, PGR, PGT), 2. Access route (HEAR, DARE, mature, traditional entry) and 3. Institution type (University, IoT). Participants who fell into overlapping categories (e.g., HEAR and DARE; n = 154) were removed to facilitate analyses. Initial analyses were conducted using both full and random samples adjusting for unequal sample sizes in different cohorts. Statistical outcomes did not differ using these sampling procedures. Therefore, full cohorts are reported. Comparisons across institutions were conducted for undergraduate students only, given the smaller number of postgraduate responses from IoT students. Data were not missing completely at random and level of missingness per item ranged from 2.2 to 22.2%, with percentages of missingness increasing towards the end of the survey, possibly indicating response fatigue. We have included information on item-level response missingness for variables included in the analysis in supplementary materials. One-way analysis of variance tests (ANOVAs) were used to identify significant differences in continuous variables across student cohorts and Scheffe post-hoc tests identified the source of these differences. To control for type 1 error in multiple comparisons, only values of p < 0.01 were reported as statistically significant. Chi-square tests of Independence were conducted for categorical variables and standardised residuals were evaluated to indicate sources of significance. Only Chi values of p < 0.01 and standardised residuals ± 2 were reported as significant. Given the potential moderating role of age, gender and international status on student mental health, Analysis of Covariance tests (ANCOVAs) controlling for the effects of age, gender and international status were also conducted to determine whether potential differences between cohorts remained significant. The statistical outcomes observed when controlling for these variables did not largely depart from the outcomes seen when these covariates were not controlled. To ensure parsimony, analyses without controlling for covariates are presented, except for analyses by degree type, where ANCOVA controlling for age is presented, given age differences between postgraduates and undergraduates. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26. Reliability analyses for standardised scales and Chi-square analyses are presented in supplementary materials.

Results

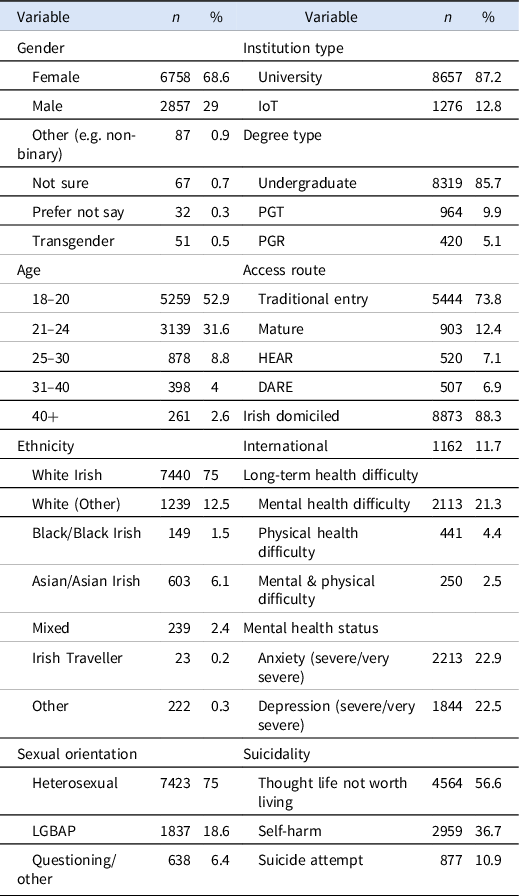

Socio-demographic characteristics, depression, anxiety and suicidality for the overall sample are summarised in Table 1. The sample contained 1276 IoT students (2.2% response rate) and 8657 university students (10.6% response rate); 71% of the sample were female, 85% were aged 23 and under. For each cohort (degree type, access route, institution type), mental health variables will be presented, followed by risk and protective factors.

Table 1. Characteristics of study sample (N = 9935)

LGBAP = Lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, pansexual; PGT = postgraduate taught; PGR = postgraduate research; HEAR = Higher Education Access Route; DARE = Disability Access Route to Education.

Degree type

Undergraduates exhibited significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety (see Table 2), and were more likely to have engaged in self-harm (χ2 = 41.51, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (χ2 = 12.53, p < 0.001) and had more days absent from college (χ2 = 181.32, p < 0.001) than PGR and PGTs.

Table 2. Summary of one-way analysis of covariance for continuous variables across undergraduate, postgraduate taught and postgraduate research students

UG = Undergraduate; PGT = Postgraduate taught; PGR = Postgraduate research.

Undergraduates demonstrated higher levels of alcohol use than PGRs and PGTs and higher drug use than PGRs (Table 2), but PGR and PGT students were more likely to have engaged in risky sexual behaviours (χ2 = 36.25, p < 0.001) and to have been forced/pressured to have sex against their will (χ2 = 24.69, p < 0.001). Postgraduates also experienced more cumulative stressors (χ2 = 127.64, p < 0.001): PGTs were more likely to be highly stressed about their current financial situation (χ2 = 19.22, p = 0.004) and to rate the future, finances and their job as top stressors. PGRs reported the future as a top stressor, while undergraduates were more likely to report exams and friends as top stressors (see supplementary materials).

As Table 2 shows, PGR and PGT students exhibited higher levels of resilience, self-esteem, social support, problem focused coping, life satisfaction and lower avoidant coping than undergraduates. With regard to help-seeking, PGR and PGT students were less likely to report a long-term health difficulty to college disability services (χ2 = 74.91, p < 0.001) and PGRs were less likely to seek professional help for mental health problems, even when they felt help was needed (χ2 = 21.22, p = 0.002). Nonetheless, PGR and PGT students reported that they were more likely to report intentions to talk about (χ2 = 38.88, p < 0.001) and avail formal supports for mental health concerns, particularly doctors/General Practitioners (GPs) (χ2 = 105.37, p < 0.001) and psychiatrists (χ2 = 48.22, p < 0.001).

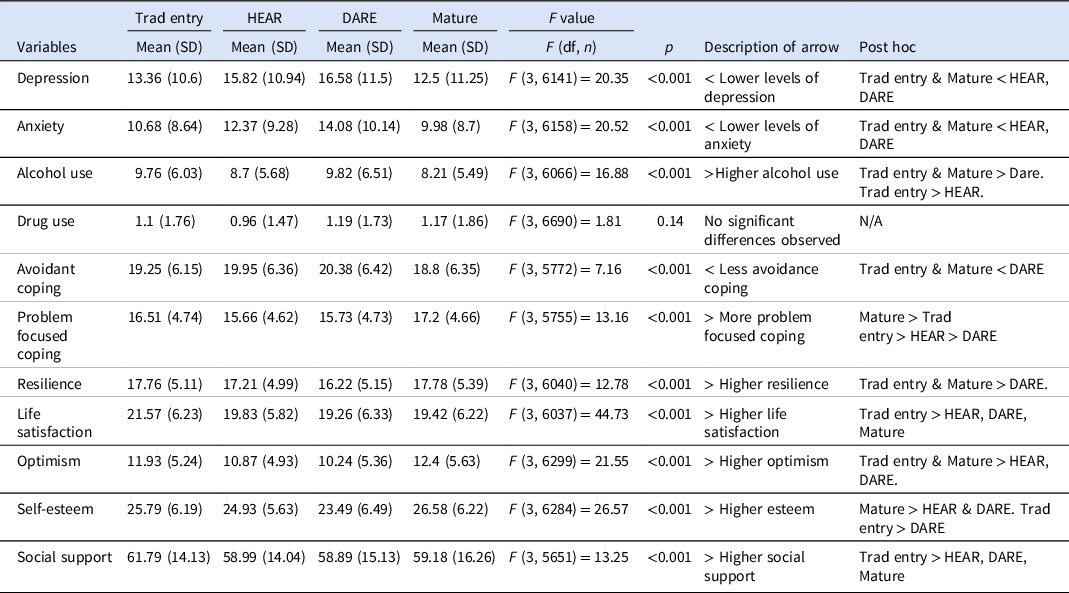

Access route

HEAR and DARE students exhibited significantly higher levels of depression and anxiety (see Table 3), greater likelihood of self-harm (χ2 = 94.78, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (χ2 = 49.99, p < 0.001), and higher absenteeism from college (χ2 = 41.96, p < 0.001) than mature and traditional entry students. HEAR, DARE and mature students were more likely to report having made a suicide attempt (χ2 = 221.74, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Summary of one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables across traditional entry, HEAR, DARE and mature access routes

Trad Entry = Traditional Entry; HEAR = Higher Education Access Route; DARE = Disability Access Route to Education; N/A = not applicable.

Traditional entry and DARE students exhibited greater alcohol use than other access routes (see Table 3), but mature students were more likely to have smoked cannabis (χ2 = 46.04, p < 0.001). Mature and HEAR students were more likely to report that they had engaged in risky sexual behaviour (χ2 = 162.77, p < 0.001) and to have been forced/pressured to have sex against their will (χ2 = 31.11, p < 0.001). HEAR and mature students reported greater exposure to cumulative stressors (χ2 = 414.06, p < 0.001) and were more likely to be highly stressed about financial pressure (χ2 = 67.35, p < 0.001). HEAR students also reported greater pressure to work outside of college (χ2 = 36.23, p < 0.001). Although all groups reported college, exams and finances as top stressors, traditional entry and DARE students were more likely to report friends as a top stressor, while HEAR, DARE and mature students were more likely to report family as a top stressor and to have a parent with a long-term mental health and/or addiction problem (χ2 = 206.71, p < 0.001; see supplementary materials).

As Table 3 shows, traditional entry and mature students scored higher than HEAR and DARE students on resilience, optimism and scored lower in avoidant coping. Traditional entry students scored highest on life satisfaction and social support, while mature students scored highest on self-esteem and problem-focused coping. In terms of help-seeking, mature and DARE students were more likely to avail of college educational supports (χ2 = 935.19, p < 0.001), and seek professional help for mental health difficulties when needed (χ2 = 200.87, p < 0.001), from doctors/GPs (χ2 = 233.77, p < 0.001) and psychiatrists (χ2 = 178.00, p < 0.001). Mature and DARE students were more likely to report having a long-term mental health difficulty (χ2 = 10005.20, p < 0.001), and DARE students were more likely to disclose this to college disability services (χ2 = 3256.21, p < 0.001).

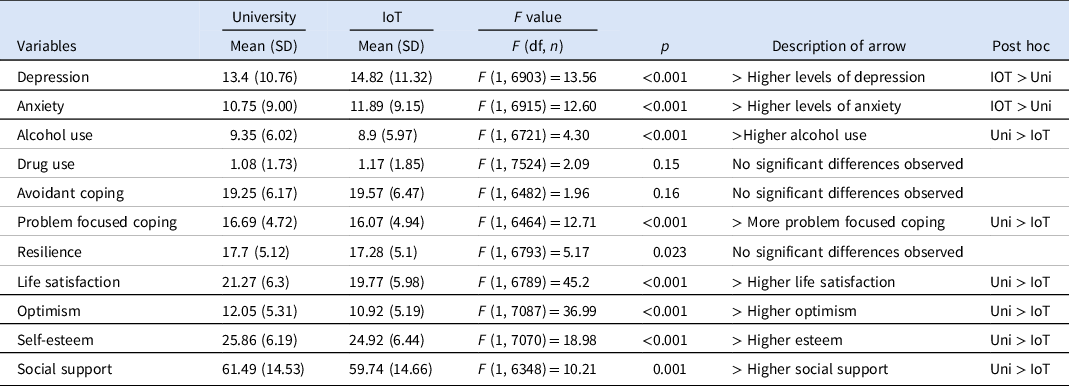

Institution type

Students attending IoTs showed higher levels of depression and anxiety (see Table 4) and were more likely to have made a suicide attempt (χ2 = 12.49, p < 0.001) than university students.

Table 4. Summary of one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables across university and institute of technology students

Uni = University; IoT = Institute of Technology.

University students showed higher levels of alcohol use, but there were no observed differences in drug use across institution type. IoT students reported greater financial stress (χ2 = 67.35, p < 0.001) and pressure to work outside of college (χ2 = 36.23, p < 0.001). IoT students were also more likely to have a parent with a mental health and/or addiction problem (χ2 = 31.13, p < 0.001) and to have engaged in risky sexual behaviours (χ2 = 34.23, p < 0.001).

University students scored higher than IoT students across all protective factors, except for resilience and avoidance coping where no significant differences were observed (Table 4). Analyses indicated there were no differences in the likelihood of using college educational supports or in the reporting of long-term health difficulties to college disability services, but IoT students were more likely to report having a long-term mental/physical health difficulty (χ2 = 13.29, p < 0.001). There were also no observed differences in the likelihood of reporting help-seeking, but for help-seeking intentions, IoT was students less likely to avail of all sources of support/information for mental health, except for Jigsaw and college lecturers (see supplementary materials).

Discussion

Poor student mental health is globally recognised as a pervasive and problematic issue (Hunt & Eisenberg, Reference Hunt and Eisenberg2010; Auerbach et al., Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet and Cuijpers2018). Aligning with international research, our findings concur that many Irish students experience mental health difficulties, with about one-fifth experiencing severe/very severe depression and anxiety and over 10% reporting a suicide attempt. It is important to note that these data were collected before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020. Research conducted since the pandemic indicates further deteriorations in student mental health (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, McGinnis, Bai, Adams, Nardone and Devadanam2020). This underscores the importance of identifying ways to effectively support student mental health through the comprehensive identification of risk and protective factors.

Consistent with some previous research, PGT and PGR students exhibited lower levels of depression and anxiety, self-harm and suicidal ideation than undergraduates (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Gollust, Golberstein and Hefner2007; Wyatt & Oswalt, Reference Wyatt and Oswalt2013). This finding might be anticipated, given that mental health difficulties tend to peak in late-adolescence/early adulthood – a time which coincides more so with undergraduate education (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Üstün2007). Additionally, while postgraduates reported greater exposure to stressors, they evidenced lower absenteeism from college than undergraduates, scored higher across all protective factors and exhibited more adaptive coping. Of note, undergraduates were more likely to score in problematic ranges for alcohol consumption. Given associations between maladaptive coping and alcohol use (Metzger et al., Reference Metzger, Blevins, Calhoun, Ritchwood, Gilmore, Stewart and Bountress2017), findings suggest that undergraduates may not have developed the coping resources to deal with stressors in the same way postgraduates have (Towbes & Cohen, Reference Towbes and Cohen1996).

Consistent with the literature on help-seeking, while postgraduates were more likely to use mental health supports, they were less likely to report mental health difficulties to college disability services. This was particularly evident for PGRs, who were less likely to seek professional help for problems even when they felt it was needed; this has been attributed to the academic culture of high achievement which often impedes help-seeking among this cohort (Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Wilson and Levecque2018). Other differences between postgraduate cohorts were minimal, except that PGRs had fewer financial concerns than PGTs, which might be expected given limited scholarship funding available for taught postgraduate programmes.

Analysis of access routes indicated that DARE students were a particularly vulnerable group. They demonstrated higher levels of depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicidal ideation and were more likely to have made a suicide attempt. DARE students also scored lowest on protective factors and tended to score in harmful ranges for alcohol use. This might be expected given that mental and/or physical disabilities increase the risk of mental health difficulties (Coduti et al., Reference Coduti, Hayes, Locke and Youn2016; AHEAD, 2018). Research suggests that stressors including stigma or negative attitudes towards disabilities and fewer psychological or environmental supports/accommodations may also contribute to heightened psychological distress of students with disabilities (Coduti et al., Reference Coduti, Hayes, Locke and Youn2016; Seidman, Reference Seidman2005). However, on a more positive note, DARE students were more likely to report that they would use formal supports for information/support regarding their mental health when needed, which supports previous findings that students with greater distress are more likely to know about and use services when needed (Rosenthal & Wilson, Reference Rosenthal and Wilson2008; Yorgason et al., Reference Yorgason, Linville and Zitzman2008). Considering this finding, it is important to note that as DARE students are linked up with college support services on enrolment, this may make accessing ongoing or future mental health supports easier or more acceptable.

Students on the HEAR access route were also vulnerable, as they were more likely to be in the severe ranges for depression and exhibited elevated levels of self-harm and suicidal ideation. They reported high levels of financial concerns and pressures to work outside of college, which can negatively impact mental health (McLafferty et al., Reference McLafferty, Lapsley, Ennis, Armour, Murphy and Bunting2017; Stallman, Reference Stallman2010). Additionally, HEAR students exhibited greater cumulative stressors, which may be indicative of the broader risks associated with lower socioeconomic status and not just financial pressures alone (Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, Berona, Busby, Eisenberg, Zheng and Pistorello2020a). HEAR students were also less likely to talk about or seek help for problems, even when they felt professional help was needed. This is consistent with the literature which finds that students from lower socioeconomic status groups tend to be less financially resourced, receive less familial support and exhibit poorer help-seeking (Thomas, Reference Thomas2014).

The literature suggests that mature students may be at increased risk of poor mental health because of pressures associated with balancing college work with family/work responsibilities (Tones et al., Reference Tones, Fraser, Elder and White2009). Although mature students in this study experienced greater numbers of stressors, they appeared to successfully manage those stressors through help-seeking and adaptive coping. Mature students were more likely to be in normal ranges for depression and anxiety and less likely to self-harm or have suicidal ideations. They also tended to score in low risk ranges for drug and alcohol use and to score highly on protective factors. Nonetheless, financial and family concerns, which were rated as top stressors in this study, are consistently reported to negatively impact on the mental health of mature students and should be taken into consideration (Creedon, Reference Creedon2015; Tones et al., Reference Tones, Fraser, Elder and White2009).

Students attending IoTs were more likely to have a mental or physical health difficulty, to score in severe ranges for depression and anxiety and to have made a suicide attempt than university students. IoT students also experienced greater numbers of stressors and with the exception of self-esteem, they scored lower across all protective factors and were less likely to avail of most mental health supports. Although research has not directly compared mental health status of Irish students across institution type before, findings are consistent with international literature, where students at community colleges have more severe psychological concerns than university students. This has been attributed to differences in student demographics, cultural issues, motives for attending community college and institutional mental health resources which are somewhat reflected in this study (Katz & Davison, Reference Katz and Davison2014).

Limitations and future directions

Compared to national data provided by HEAs in the Irish Student Survey (2020), this sample contained an overrepresentation of females (71% of our respondents were female, while nationally 53% of students are females) and younger students (85% of our participants were aged 23 and under, while 56% of all students nationally are aged 23 and under) which may have introduced selection bias. There were also disproportionately fewer IoTs (we sampled from 5/14 IoTs; 37.5% response rate) than Universities (we sampled from 7/7 universities; 100% response rateFootnote 2) in this convenience sample. Findings may be particularly impacted by the over-representation of females who are at increased risk of mental health difficulties (Bayram & Bilgel, Reference Bayram and Bilgel2008). Additionally, the inferences that can be drawn about IoT students may be limited given their disproportionately low representation in this sample (12% IoT versus 87% University students). Furthermore, as these data reflect a response rate of 11% for University students and 2% for IoTs, findings might not be generalisable to the entire Irish student population despite the large sample. The data were self-report and contained missing data, particularly towards the end of the survey, which may have also introduced elements of bias into the study.

There were other demographic differences between student cohorts which may have increased the risk of mental health difficulties; for example, HEAR students were more likely to belong to ethnic minority groups and DARE students were more likely to belong to gender and sexual minorities which have been associated with increased risk of mental ill-health (Hefner & Eisenberg, Reference Hefner and Eisenberg2009; Smithies & Byrom, Reference Smithies and Byrom2018). Further research is required to parse out the intersection of relationships between disability, socioeconomic status, ethnic and gender identities and mental health outcomes. Future research should also incorporate institutional factors (e.g., institute culture, academic requirements, service availability) which were not captured by this study but can influence mental health outcomes (Wyatt & Oswalt, Reference Wyatt and Oswalt2013). Additionally, study findings were largely descriptive, but future work could extend these findings by building models that predict the extent to which these risk/protective factors contribute to mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety. Further research on IoT student mental health is also required to build on our exploratory findings. Recruiting IoT students to participate was more challenging because of structural differences in how IoTs centralise data and communicate with students versus universities, therefore future studies should adopt diverse sampling strategies to recruit representative samples from IoTs. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal relationships or time trends to be established. Further waves of data collection are required to develop a robust evidence base and to track trends in student mental health over time.

Recommendations

To support student mental health, it is important to consider the risk and protective factors salient across degree type, access route and institution type. While supporting the mental health of all students is important, findings suggest that students attending IoTs and those on HEAR and DARE admission routes are particularly vulnerable groups that may need to be prioritised in terms of services to support student mental health. As noted in the National Suicide Prevention Framework (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Byrne, Surdey, Team, Woods and O'Donovan2020), there is a need not only to provide universal mental health supports for students, but also to establish systems to support students with more acute needs. Findings also point to the protective role of adaptive coping strategies and highlight the potential benefit of stress management and self-regulation skills workshops that teach ways to reframe unhelpful thoughts and cope effectively with stress (Saber et al., Reference Mahmoud, Staten, Hall and Lennie2012; Shigeto et al., Reference Shigeto, Laxman, Landy and Scheier2021). Continued signposting of student mental health supports, help-seeking campaigns and provision of education/training on student mental health to academic staff and supervisors could also help improve help-seeking and disclosure of mental health concerns among students (Wyatt & Oswalt, Reference Wyatt and Oswalt2013; Metcalfe et al., Reference Metcalfe, Wilson and Levecque2018).

Conclusion

This research has comprehensively profiled risk and protective factors and detailed levels of mental health difficulties and suicidality across student cohorts. Findings suggest that differing vulnerabilities and strengths across student cohorts need to be considered to ensure effective student support and service provision.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Cliodhna O Connor and the research assistants involved in data collection.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the host institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Financial support

This project was funded by Jigsaw – The National Centre for Youth Mental Health (CHY 17439) and the ESB Energy for Generations Fund.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2021.85