Introduction

Irish Travellers are an indigenous minority group in Ireland, first officially recognised by the Irish Government in March 2017 (Joint Committee on Justice and Equality, 2017). They are distinct in their culture, language, value system originating from their nomadic tradition (Gmelch & Gmelch, Reference Gmelch and Gmelch1976; Ni Shuinear, Reference Ni Shuinear, McCann, Siochain and Ruane1994). The Equal Status Acts (Government of Ireland, 2016) defines Travellers as: ‘The community of people who are commonly called Travellers and who are identified (both by themselves and others) as people with a shared history, culture and traditions, including an affinity to a nomadic way of life on the island of Ireland’.

Travellers are a marginalised group in Ireland and suffer disadvantage and social exclusion due to discrimination, poverty and unemployment. They have known poorer outcomes and health status than the general population, as highlighted in the findings of the All Ireland Traveller Health Study (AITHS). The overall Traveller life expectancy was 66 years, that is, 15 years less for Traveller men and 11 years less for Traveller women. The Traveller mortality rate is 3.5 times higher and the infant mortality rate is 4 times higher than the general population (All Ireland Traveller Health Study Team, 2010).

Whilst several review studies have looked at the health of Travellers, the focus has by and large been on physical health, vaccine uptake and outreach programmes with little emphasis on mental health and suicide. Yet, the findings from AITHS show high levels of mental ill-health, and frequent mental distress (FMD) has shown to be associated with key life events including experience of discrimination and bereavement (McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Hamid, Fitzpatrick, Daly, Malone and Kelleher2013). There has been some research done by Mac Greil (Reference Mac Gréil1996, Reference Mac Gréil2010) which shows that Irish Travellers are exposed to the risk of discrimination on a daily basis in all aspects of their lives. This was further confirmed by a recent report commissioned by the Economic, Social and Research Institute where they found that Travellers were 22 times more likely to experience discrimination. (McGinnity et al. Reference McGinnity, Grotti, Kenny and Russell2017). There is a wide range of international publications (Karlsen, Reference Karlsen2007; Paradies et al. Reference Paradies, Ben, Denson, Elias, Priest and Pieterse2015) which highlight the association between the experience of discrimination and low self-esteem, suicidal tendencies, mental health and psychological stress. We explore the links between experience of discrimination in Travellers and engagement with Mental Health Services in an accompanying paper (Quirke et al. Reference Quirke, Heinen, Fitzpatrick, McKey, Malone and Kelleher2020).

Rapid reviews are best designed for new or emerging research topics (Ganann et al. Reference Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2010). Here, we present a rapid review of Traveller mental health and suicide, exploring the extent, type and nature of research to date, from a psycho–socio–anthropological perspective (as per the IJPM special edition brief).

Methods

A rapid review is described as a form of knowledge synthesis in which components of the systematic review are simplified with a rapid analysis and dissemination of the topic that still allows for a comprehensive literature exploration. It speeds up the systematic approach by omitting some stages, making it valuable but less rigourous.

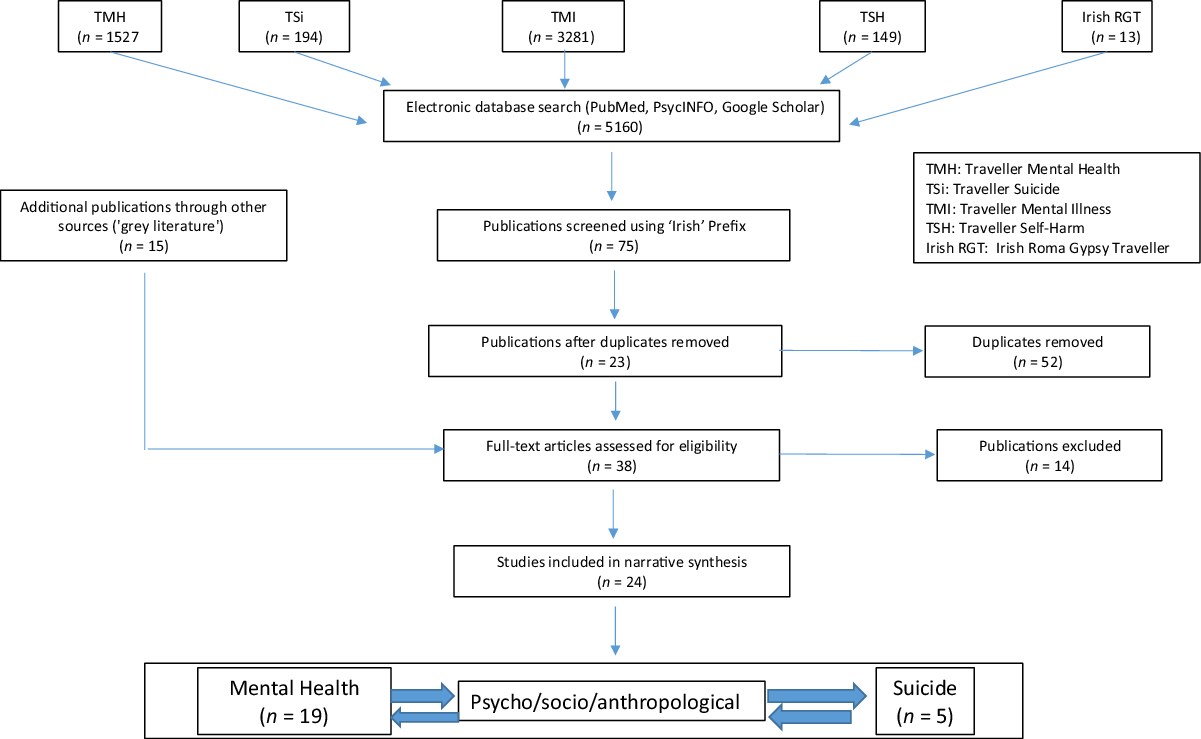

The analysis broadly followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). Electronic searches of PubMed, PsycINFO and Google Scholar were performed with earliest records till January 2020. Search words included (‘Traveller’ OR OR ‘Gypsy Travellers’) and (‘Mental health’ OR ‘Mental illness’ OR ‘Suicide’ OR ‘Self-harm’). A further search of ‘Irish Traveller in United Kingdom/UK’ was also included. Given the broad initial scope, including International Infectious Disease and Traveller health, ‘Irish’ was added as a prefix.

For PubMed publications, searches were sorted by ‘best match’ rather than ‘most recent’ to optimise the search. Once read, all articles were then screened for search words including ‘mental health’ ‘mental illness’, ‘suicide’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘stress’ and ‘nerves’. Initially, three reviewers (SM, KMM, CCK) independently read all identified titles and abstracts. Duplicates were removed. Selected articles were then reviewed by two reviewers, with disagreements being arbitrated between three (SM, KMM, CCK) and final adjudicator KMM. Reference lists of all articles were checked for additional relevant publications (including grey literature).

Eligibility study criteria included:

(i) Individuals identifying as Irish Travellers in Ireland or the United Kingdom and or/Gypsy Travellers,

(ii) Information relevant to mental health/mental illness/suicide/self-harm,

(iii) Psychosocial anthropological perspectives on indices of mental health.

a. Studies were rated as having an anthropological perspective based on whether they referenced cultural or societal meaning and a holistic approach in their recruitment, design or findings.

b. Indices of mental health are the following:

i. Depression,

ii. Anxiety,

iii. Suicide,

iv. FMD,

v. Alcohol and substance misuse,

vi. Morbid grief.

(iv) Publication in english.

A flowchart of the literature screening is presented in Fig. 1. Data, including study characteristics (e.g. authors, date of publication), study methodology (e.g. recruitment, measures used), participant characteristics and study results (e.g. prevalence or incidence data and associations between variables of interest) were extracted using a spreadsheet template (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Rapid review of peer-reviewed publications in the scientific literature: study selection.

Table 1. Peer-reviewed published scientific studies related to Traveller mental health and suicide (n = 5)

Results

Twenty-four papers fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in the review from the initial 5160 references (Fig. 1). Due to the small sample size and considerable heterogeneity in study design, a meta-analysis was not used. Results were synthesised narratively to produce a descriptive, hypothesis-generating study of mental health and suicide in Irish Travellers. Results were grouped into those that included a reference to Traveller mental health (n = 19) (Table S1, in Supplementary material) and those that referred specifically to suicide amongst Travellers (n = 5), (Table 1). The studies included quantitative (n = 10), qualitative (n = 12) and mixed-method studies (n = 2), with the majority being qualitative; as well as whether studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 14) or Ireland-based (n = 10).

As shown in Table 1, participant numbers ranged from 7 to 1947, with a large range in age group across studies, and the majority of studies ranging from teen to older adult. Gender was commented on frequently; with the majority of participants in each study being female. One study focused primarily on males in relation to their social attitudes to healthcare inequality, however, the study still included a female focus group (Hodgkins & Fox, Reference Hodgins and Fox2014).

A variety of recruitment strategies were identified. These included ‘snowballing’ where participants are selected by word of mouth; quota sample; specialist health visitor; general practitioner records and public health records. Some used a combination approach (such as agency introduction and health visitor) or incorporated a predevelopment phase to increase trust and participation with the study. Interview, including structured, semi-structured, non-directive and explorative was a common method of data collection, with the majority being subsequently transcribed from recordings.

Out of all the 24 studies, the majority discussed mental health with a focus mainly on depression and anxiety (n = 19), (Table S1, in Supplementary material). Five studies included specific mention of suicide in their findings (Table 1), predominantly in the qualitative analysis versus quantitative; with one study looking at the in-depth experience of suicide in using science–arts methodology (Malone et al. Reference Malone, McGuinness, Cleary, Jefferies, Owens and Kelleher2017). All studies were considered to have an anthropological approach (n = 24) in their recruitment, design or overall findings. Five studies included all three (mental health, suicide and an anthropological perspective) (Table 1).

Of the 10 quantitative papers, form both tables, 2 focused primarily on mental health with an inclusion of suicide in Travellers. The remainder concentrated on overall health status, including depression and anxiety, access to health services, injury and addiction

The largest of the studies examined was the AITHS; it was a community-based cross-sectional census survey of all Traveller households on the island of Ireland in 2008 and 2009. (All Ireland Traveller Health Study Team, 2010). The AITHS included an overall census of 7042 Traveller families followed by a random selection of an individual member of the family to answer either a health status or a health utilisation questionnaire. A paper based on the health utilisation survey comprised a sub-sample of 1947 Traveller participants. Respondents were found to have adequate access to care, with increased use of the accident and emergency services including mental health services, but overall reported significantly poorer quality healthcare experiences and trust in healthcare professionals compared to national survey data (McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Frazer, Daly, Moore, Turner and Sweeney2012).

The second AITHS paper focused on disparities in fatal and non-fatal injuries in the Traveller population compared with the general public. Findings showed increased intentional injury, including suicide and self-harm in the Traveller population. Men were 6 times and women 4 times more likely to have an intentional injury, of which the majority were suicide deaths (Abdalla et al. Reference Abdalla, Kelleher, Quirke and Daly2013).

FMD was utilised as an outcome for poor mental health in the context of known variables of mental health. Travellers were found to have 2.5 times higher rates of FMD than the general population. Significant associations with FMD included poor physical health or inability to partake in regular activity due to illness, death of a family member, as well as the experience of discrimination and perceived discrimination, psychosocial factors that are predictive of FMD. Those with higher educational attainment also proved to have a higher risk of FMD (McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Hamid, Fitzpatrick, Daly, Malone and Kelleher2013).

Three studies in the United Kingdom looked at overall health status in Travellers compared to lower sociodemographic groups and other ethnic groups (including African Caribbean, Pakistani Muslim and White residents) (Van Cleemput et al. Reference Van Cleemput and Parry2001; Parry et al. Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Parry, Van Cleemput, Moore, Cooper and Walters2009). The largest of these (n = 293) found that depression and anxiety were two and three times higher, respectively, than that of the general population (Parry et al. Reference Parry, Van Cleemput, Peters, Walters, Thomas and Cooper2007). Travellers were at increased risk of accidents, long-term illness, pain/discomfort and decreased activity relative to the comparison group. All studies adjusted their design using colloquial terminology of ‘nerves’ and ‘fed up’ as substitutes for ‘anxiety’ and ‘depression’ as an approach to consider cultural context, and showed increased levels of same than when using the formal terms.

Travellers were noted to be overrepresented in forensic psychiatry admissions as well as in addiction services (Linehan et al. Reference Linehan, Duffy, O’Neill, O’Neill and Kennedy2002; Van Hout & Connor, Reference Van Hout and Connor2008; Carew et al. Reference Carew, Cafferty, Long, Bellerose and Lyons2013). One study focused primarily on Traveller males’ social position as a determinant for health inequality and described a strong fear of not being able to provide for their family as a result of poor prospects (Hodgins & Fox, Reference Hodgins and Fox2014). Addiction attitudes were noted to be the same as the general population but Travellers described lower levels of education of services available (Hodgkins & Fox, Reference Hodgins and Fox2014).

Of the five studies that made specific reference to suicide (Table 1), four were conducted in Ireland. Of these, the leading quantitative study calculated a Standardised Mortality Ratio for suicide amongst Travellers in Ireland, and reported an SMR of 6.6 for young adult males (Abdalla et al. Reference Abdalla, Kelleher, Quirke and Daly2013). The qualitative studies focussed on aspects of mental illness and postvention themes and impacts of bereavement, grief and loss through suicide ((McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Hamid, Fitzpatrick, Daly, Malone and Kelleher2013; Malone et al. Reference Malone, McGuinness, Cleary, Jefferies, Owens and Kelleher2017; Tobin et al. Reference Tobin, Lambert and McCarthy2018; Millan & Smith, Reference Millan and Smith2019).

Narrative synthesis

The majority of the qualitative literature examined Travellers’ and Gypsies’ attitudes to health and services is summarised in Table 1. The resulting narrative synthesis (Fig. 2) yielded 21 broad recurring themes, which fell into three interrelated strands, including ‘Traveller traits’, ‘perceived social impacts’ and ‘psycho/socio/anthropological consequences’. Each of these strands provided insights into ‘the life struggle’ which is common to indigenous ethnic minorities. Within and across each of the strands there are also insights into life-affirming qualities and behaviours, which are also common (and not always recognised) within indigenous ethnic minorities, and this is very apparent in this literature.

Fig. 2. Narrative synthesis of qualitative papers (n = 12) on Traveller mental health and suicide.

Discussion

This rapid review identified a very small number of published peer-reviewed scientific studies that have addressed the issue of mental health and suicide in Irish Travellers. Despite there being a burgeoning mainstream scientific literature on many biological, psychological and social facets associated with understanding suicide in society (Mann et al. Reference Mann, Waternaux, Haas and Malone1999; Fazel & Runeson, Reference Fazel and Runeson2020), this rapid review identified only 24 peer-reviewed scientific publications over the past 20 years examining Traveller mental health. Of those, five have examined determinants of mental health and included the word ‘suicide’. Only a handful of studies included a mention or consideration of combined psychiatric, psychological and anthropological perspectives, all of which make this rapid review timely. All studies report that this is a serious issue, but it is both under-researched and to date under-resourced, with formidable service delivery challenges in a hard-to-reach and economically marginalised community (Walker, Reference Walker2008; McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Hamid, Fitzpatrick, Daly, Malone and Kelleher2013). Although less nomadic on the island of Ireland than in the past, there is still much movement between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. It is now a decade since the large-scale government-commissioned census AITHS first reported its findings and there has been little systematic peer-reviewed research published since, based on this review.

A psycho/socio/anthropological perspective

Science is one of the most important channels of knowledge. It has a specific role, as well as a variety of functions for the benefit of our society: creating new knowledge, improving education and increasing the quality of our lives. Science must respond to societal needs and global challenges, (UNESCO.org). Travellers are an indigenous minority group in Ireland, with poorer life expectancy and health status than the general population (All Ireland Traveller Health Study Team, 2010). The Irish Travellers show many features in common with other indigenous ethnic minority (IEM) populations. Mental health is interrelated with incarceration, substance misuse, bereavement, domestic violence and social supports, which have been identified as contributing factors in the general population, however, Travellers often experience increased levels of such (Goward et al. Reference Goward, Repper, Appleton and Hagan2006; AITHS, 2010, Van Hout, Reference Van Hout2010; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Richer and Harper2016; Tobin et al. Reference Tobin, Lambert and McCarthy2018; Dickson et al. Reference Dickson, Cruise, McCall and Taylor2019). Discrimination, educational disadvantage and social exclusion are increasingly prevalent in this community (Pavee Point, 2013), all of which have been implied as aggravating factors of poor mental health (O’Shea, Reference O’Shea2011).

Elevated suicide rates in young male Irish Travellers appear to be a relatively modern phenomenon which has developed over the past two decades or so (AITHS, 2010; McLoughlin et al. Reference McLoughlin, Gould and Malone2015). However, as with the Irish general population, this may have been under-reported due to stigma (Walker, Reference Walker2008; AITHS, 2010; Carew et al. Reference Carew, Cafferty, Long, Bellerose and Lyons2013) particularly in a country and community with strong religiosity. The topic of suicide has appeared in some published reports conducted by local authorities or local community health services (more so in the UK), but the findings from these reports rarely subsequently appear in the scientific literature, and therefore don’t appear in literature searches. Even our exploration of the grey literature did not shed much additional light on our search for data related to suicide risk observed amongst this particular IEM.

It is not altogether surprising that suicide is a problem in Travellers, as similar patterns have been observed in other indigenous ethnic minorities globally (Inuits, Sami, Aboriginals, Maoris, Torres Straits Islanders, First-Nation Canadians), where the experience of discrimination is a common thread. (Elliott-Farrelly, Reference Elliott-Farrelly2004; Bellamy and Hardy, Reference Bellamy and Hardy2015, Chachamovich et al. Reference Chachamovich, Kirmayer, Haggarty, Cargo, McCormick and Turecki2015, Kral, Reference Kral2016; Pollock Reference Pollock, Healey, Jong, Valcour and Mulay2018a, Reference Pollock, Healey, Jong, Valcour and Mulay2018b). The usual issues of alcohol and substance abuse have significant impacts for health and mental health including suicide in young Traveller men (Van Hout & Connor Reference Van Hout and Connor2008), but they cannot account solely for such an elevated SMR (AITHS, 2010).

When a tribe (www.brittanica.com) experiences a multigenerational and not entirely implausible fear of extinction, secondary to discrimination, inequality, prejudice, exclusion, stigma, and racism experienced from the outset, fear and anxiety will be apparent. In these circumstances, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness and accelerated social fragmentation could move suicide to the fore (Van Orden et al. Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010; Hatcher & Stubbersfield, Reference Hatcher and Stubbersfield2013; Hatcher, Reference Hatcher2016). There is a substantial cultural taboo around suicide within the Travelling community, with such an event being perceived and experienced as a betrayal of the tribe, especially when deep spirituality is such a cornerstone of their cultural beliefs (Walker, Reference Walker2008) and yet it happens in significant numbers, bringing with it significant individual and community bereavement, with young peer grief in particular (Sweeney et al. Reference Sweeney, Owens and Malone2014). This, in turn, may contribute to a post-modern suicide contagion impacted by over-identifying with the counterculture anti-hero image which may be ascribed to the deceased, and which may influence young adult (and adolescent) peers, in particular, becoming inscribed in the tribal code, sometimes referred to as ‘peer deviant affiliation’ (Gillies et al. Reference Gillies, Boden, Friesen, Macfarlane and Fergusson2017).

The Science–Arts Lived Lives project (Malone et al. Reference Malone, McGuinness, Cleary, Jefferies, Owens and Kelleher2017) brought Travellers, clinical scientists and policymakers together towards confronting suicide in their community, allowing Travellers to open up and speak about their suicide bereavement experience and calling for action to intervene by whatever means possible. Indeed, recently, it has been reported anecdotally by Travellers that the problem has now ‘spread’ to female Travellers in increased numbers also, further supporting the possibility of contagion. Such is the level of anxiety amongst Travellers that they themselves are known to organise community suicide watch rotas, whereby designated Travellers will take turns to call and check in each night and morning with any Traveller family members in the site who express or are known to have expressed suicidal ideation or tendencies. Culturally competent services need to be developed in this regard. This was a key recommendation from the original AITHS and remains pertinent today.

Due to chronic under usage of mainstream health services (and the attendant obstacles that exist for Travellers accessing healthcare), the Traveller health response seems to focus on emergency department (ED) assessment and input, where the ED is seen as the only resort as well as the last resort for their health (and mental health) needs. On the other hand, the ED is configured to triage and prioritise the most ill, and may not understand the crisis-led life and death culture observed in Travellers, contributing to communication breakdown and mutual mistrust (Beach, Reference Beach2006; McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Frazer, Daly, Moore, Turner and Sweeney2012). This is a further opportunity where cultural competence can impact.

Research is urgently required to understand the cultural, community and healthcare reverberations of suicidality in Travellers, drawing on what is known from studies in other IEMs, and also designing scientifically robust community health studies in Ireland to better inform policy (locally and internationally). The problem of such elevated suicide rates in Travellers must be included in studies of cultural competence, which can inform obstacles to healthcare, and mental healthcare in particular (Francis, Reference Francis2013) and to understand more about why Travellers have such a fear of mental illness, and of psychiatric care (O’Shea, Reference O’Shea2011). The AITHS suggested the need for inclusion of ethnic identifiers in mental health data sets, both inpatients and outpatients, so we can get accurate disaggregated data on mental health diagnosis, referrals, treatments, admissions and mortality rates for Travellers, particularly suicide. It would also make doing research in this area more feasible.

Evidence from our review suggests that current research strategies tend towards qualitative research, and themes appear to have become saturated around recurrent findings and are consistent even when asked in different contexts including maternal care, health attitudes and addiction services. The ‘travelling way’, stoicism, self-reliance, discrimination, loss of identity and powerlessness are notable and prominent. Low institutional trust featured less prominently, but is often represented in the analysis of other studies (Heaslip, Reference Heaslip, Hean and Parker2016, 2018).

Interestingly, in multiple studies, Travellers speak of the ‘loss’ of freedom and nostalgia of a slower pace of life with an inability to travel and be ‘out in the fresh air’ and this loss has been correlated with increased anxiety and depression (Van Cleemput et al. Reference Van Cleemput, Parry, Thomas, Peters and Cooper2007). This has been suggested to be indicative of a loss of cultural identity, embedded in their ability to move but also possibly suggestive of a community which is relatively quickly being asked to transition from an isolated community into a global, expanding and faster-paced sphere. Similar themes have been described in other ethnic minorities. Novel strategies for engaging Travellers in research about Traveller health, ranging from the FMD study method to the science–art Lived Lives community intervention project can enhance the impact and add value, community ownership and authenticity (McGorrian et al. Reference McGorrian, Hamid, Fitzpatrick, Daly, Malone and Kelleher2013; Malone et al. Reference Malone, McGuinness, Cleary, Jefferies, Owens and Kelleher2017).

The cultural isolation, however, is not attributable only to discrimination from outsiders, as Travellers themselves have a tradition of separateness from the general population. It was interesting to note we originally identified over 5000 references by searching the term ‘Traveller’, indicating that ‘Traveller’ is a very generic description of a nomadic people living with their own culture but being inextricably linked to Ireland, and being proud of being both different and Irish. It was only when we qualified the search term to include ‘Irish’ did the Traveller-related studies appear. The term ‘Traveller’ is a generic translation from old Gaelic of how they were in older times – ‘an lucht siúil’, which directly translates to ‘the walking community’. Travellers have been called by many derogatory names (such as pikey, knacker, tinker, itinerant), and so maybe settling on a neutral/generic naming of their community in English was an acceptable compromise to both Travellers and to the society around them. Nevertheless, when identity and heritage are of such importance to indigenous ethnic minorities, a unique tribal name has added significance. Some Travellers refer to themselves in their Shelta language as ‘Minceir’ or ‘Pavee’ (Ni Shuinear, Reference Ni Shuinear, McCann, Siochain and Ruane1994; Binchy, Reference Binchy, Ni and O’Riain1995; Helliner, Reference Helleiner2000).

There is a lack of published suicide data on indigenous populations in low- and middle-income countries. Travellers were not included in a recent global systematic review of suicide in indigenous ethnic minorities (Pollock Reference Pollock, Naicker, Loro, Mulay and Colman2018b). Their study identified 13,736 papers and 99 eligible studies across 5 continents from which suicide rates amongst IEMs in 30 countries and territories were examined. This in-depth systematic review identified some of the difficulties germane to our work. Similar to other international IEMs, until recently, Irish Travellers were excluded from being linked by an ethnic identifier to the national census. Irish Traveller mental health and suicide did not feature in the global literature search for suicide in IEMs applied in the Pollock et al. systematic review (Pollock Reference Pollock, Healey, Jong, Valcour and Mulay2018a). The omission of Travellers (and Gypsy Travellers) in the systematic review also supports our call for more specific and focussed scientific research and peer-reviewed publications about Irish Traveller mental health and suicide to gain visibility, recognition and understanding at an international science level beyond our traditional borders (Ogedegbe, Reference Ogedegbe2020).

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. Small numbers/sample size; lack of ‘probability’ sample; the majority are quota; limited data on sociodemographic status; recruitment bias with low male representativeness and the majority of studies are self-reporting. Compared with a systematic review, a rapid review allowed for an expedited analysis, within 6 months of the peer-reviewed literature, augmented and expanded by the inclusion of ‘grey literature’. Initially, studies were screened by title and abstract. Given the heterogeneity of the initial yield, a retrospective analysis of all grey literature on Traveller health were reviewed and read in full. Non-peer-reviewed publications such as policies and reports were not included in the narrative analysis. This proved to be unavoidable, due to PRISMA criteria, and yet a significant limitation, as policy to date has been driven by invited submissions and commissioned research reports.

Conclusions

This paper draws together strands from the disciplines of psycho/socio/anthropological perspectives to gain deeper insights into mental health and suicide in Irish Travellers. An analysis of peer-reviewed scientific publications since the 1980s reveals our lack of knowledge around this most sensitive topic and foregrounds the likelihood of stigma contributing to this knowledge gap. In a relative knowledge vacuum, it behoves the scientific community to explain the value of scientific rigour to both policymakers as well as Travellers, embracing psychological, social and anthropological domains, and shifting the existing discourse towards new knowledge and understanding of mental health and suicide in Travellers.

Conflict of interest

The authors individually and collectively declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this rapid review was not required by their Local Ethics Committee.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.108