Introduction

The Irish Mental Health Act 2001 (MHA 2001) was enacted in November 2006 and it introduced significant changes to the process of involuntary admission for an individual affected by a mental health disorder (Kelly, Reference Kelly2002), such as a review by an independent tribunal. The objectives behind the introduction of the MHA 2001 were to provide better protection of patients’ rights and to bring practice more in line with the United Nation’s Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (United Nations, 1991; Kelly, Reference Kelly2007).

Following the introduction of the MHA 2001, a study was conducted to evaluate service user’s perspective towards their involuntary admission. The study found that before discharge, 72% of service users perceived that their involuntary admission had been necessary (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, Larkin, Feeney and O’callaghan2010) and this reduced to 60% after 1 year (O’Donoghue et al. 2011 Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, O’rourke, Daly, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghanb ). In the year following discharge, nearly two-thirds of service users engaged with their treating team and 43% were readmitted within 1 year, half of which, were involuntary (O’Donoghue et al. 2011 Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, O’rourke, Daly, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghanb ). A large study had been conducted in the United Kingdom at a similar time and this found that only 40% of individuals admitted involuntarily perceived that their admission was justified (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Amos, Leese, Morriss, Rose, Wykes and Yeeles2009). There also appears to be a wide discrepancy across Europe as to how service users reflect upon their involuntary admission, as a study conducted in 11 countries found that positive perspectives towards involuntary admissions ranged from 39% to 71% 1 month after admission and 46–86% after 3 months (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Glockner, Dembinskas, Fiorillo, Karastergiou, Kiejna, Kjellin, Nawka, Onchev, Raboch, Schuetzwohl, Solomon, Torres-Gonzalez, Wang and Kallert2010). Furthermore, there were considerably less readmissions in the UK cohort, with 26% readmitted (15% involuntary and 11% voluntary) in the year following discharge (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Amos, Leese, Morriss, Rose, Wykes and Yeeles2009).

Although the study conducted in Ireland delivered important insights into the perspectives of service users’ towards their involuntary admission, it highlighted significant discrepancies in comparison with international findings and also raised important further research and clinical questions. The more positive reflections of the involuntary admission could have been biased by the interviews having been conducted by doctors. The high readmission rate also required further investigation. The Irish study found that individuals who experienced low levels of procedural justice (i.e. those who felt unfairly treated or uninvolved in their treatment) were less willing to engage in care following their admission (O’Donoghue et al. 2011 Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, Larkin, Feeney and O’Callaghana ), suggesting that the experience of admission could subsequently influence engagement, which could lead to a higher risk of readmission. In addition, as readmission rates are an important outcome measure, other outcomes such as quality of life have been given a higher priority by service users (Renwick et al. Reference Renwick, Drennan, Sheridan, Owens, Lyne, O’Donoghue, Kinsella, Turner, O’Callaghan and Clarke2015). Finally, the research to date had tended to focus on involuntarily admitted services users, yet it is recognised that legal status is a poor proxy measure of the level of coercion perceived and experienced (Monahan et al. Reference Monahan, Hoge, Lidz, Roth, Bennett, Gardner and Mulvey1995) and therefore involvement of voluntarily admitted service users could also deliver important insights into the perception of coercion.

Therefore, in order to address the issues highlighted by the original study, a further study entitled ‘Service users perspectives’ towards their admission’ (SUPA) was conducted and the broad aims of this study were to (i) determine the proportion of service users who experience physical coercion, specifically restraint, seclusion or the administration of medication without consent; (ii) determine the level of perceived coercion, perceived pressures and procedural justice of service users admitted voluntarily or involuntarily; (iii) determine whether services users’ account of their admission varied dependent on whether the interview was conducted by a clinician or a service user researcher; (iv) identify whether there is a subgroup of voluntarily admitted service users who report high levels of perceived coercion on admission and if such a group exists, identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with this group; (v) the longer term outcomes of functioning, engagement and quality of life in the cohort.

The results of the above objectives have been published elsewhere individually and the purpose of this report is to summarise the main findings of the project, to compare the findings with international studies and to discuss possible directions for future research.

Methodology

Participants and study setting

Eligible individuals aged 18 years and who were involuntarily admitted to three psychiatric in-patient units in Dublin and Wicklow between 1 May 2010 and 30 June 2011, were invited to participate in the study. In order to have a comparable number of voluntarily admitted participants, the next voluntarily admitted service user after each involuntary admission was invited to participate. Caregivers of the service users who were admitted to two of the above psychiatric inpatients units were also invited to participate in an interview (if the service user provided consent for them to be contacted). Another cohort of caregivers were also interviewed, specifically caregivers of service users who were participants in another study entitled the ‘Prospective Evaluation of the Operation and Effects of the Mental Health Act from the viewpoints of Service Users and Health Professionals’, which included service users brought to hospital under the MHA legislation to the acute psychiatric in-patient units in University College Hospital Galway, St Brigids Hospital, Ballinasloe and the Department of Psychiatry, Roscommon County Hospital.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The MHA 2001 stipulates that individuals with a sole diagnosis of a personality disorder or substance misuse cannot be admitted involuntarily. Therefore, to have comparable samples, we excluded voluntarily admitted service users with either a sole diagnosis of a personality disorder or substance misuse. We also excluded individuals with dementia and intellectual disabilities; those with a first episode of psychosis were excluded because they were involved in another study protocol.

Assessors/interviewers

One of the aims of this study was to determine whether service users would give a different account of their admission according to the discipline of the interviewer. Therefore, participants were randomised to be interviewed by either a clinician (doctor or nurse) or service user research. Service users researchers had lived experience of mental health difficulties and had qualifications in either research methods or health sciences. The MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (AES) and the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) were conducted by the interviewer assigned by randomisation, while any of the clinical assessments [(such as the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (SCID)] were performed by a clinician. If a participant was assigned to a service use researcher by randomisation, the participant had a subsequent interview with a clinician to undertake the clinical assessments. All assessors underwent training in the instruments and inter-rater reliability was performed on the MacArthur AES and reliability (κ) ranged from 0.77 to 1.00, which is considered to be highly acceptable.

The initial baseline interviews were conducted before discharge and participants were reinterviewed 1 year after discharge and these interviews took place in the outpatient clinic.

Instruments

Diagnoses were determined using the SCID and was conducted by trained clinicians (First et al. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002). The MacArthur AES was used to determine the level of perceived coercion (scored 0–5 with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived coercion), perceived pressures (scored 0–4 with higher scores representing higher levels) and procedural justice (scored 1–4 with higher scores representing higher levels) experienced by an individual on admission to the hospital (Monahan et al. Reference Monahan, Hoge, Lidz, Roth, Bennett, Gardner and Mulvey1995). A modified version of the MacArthur AES was used for caregivers (Hoge et al. Reference Hoge, Lidz, Eisenberg, Monahan, Bennett, Gardner, Mulvey and Roth1998).

An accumulated coercive events algorithm was developed by Iversen et al. (Reference Iversen, Hoyer and Sexton2007) and it reflects a total level of coercion experienced by an individual during their admission and is based on their legal status, level of perceived coercion and the number of episodes of physical coercion (restraint, seclusion or medication without consent). The algorithm was adapted for use in an Irish setting, the main difference being that the original scale had a section for involuntarily treatment in the community and this does not apply to an Irish setting.

The CSQ-8 was used to measure the level of satisfaction of services received and it is a self-report instrument with eight items (Attkisson & Greenfield, Reference Attkisson and Greenfield2004). Engagement was measured using the Service Engagement Scale that was completed by the participants keyworker and it has four subscales measuring availability, collaboration, help seeking and adherence (Tait et al. Reference Tait, Birchwood and Trower2002). The Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised was used to measure therapeutic relationship and this is a 12 item self-report questionnaire with scores ranging from 12 to 84, with higher scores representing a better therapeutic relationship (Munder et al. Reference Munder, Wilmers, Leonhart, Linster and Barth2010).

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) was used to determine the level of functioning (Soderberg et al. Reference Soderberg, Tungstrom and Armelius2005). Subjective quality of life was assessed using the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Huxley, Knight and Evans1999) and objective quality of life using the objective social outcomes index (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Watzke, Hansson and Burns2008).

Information on the use of restraint and seclusion were obtained from the registers, in which it is a mandatory obligation to record each episode of physical coercion. Information relating to the occurrence of the administration of medication without consent was obtained from the medical records.

Statistical tests

Statistical analysis was performed using the PASW version 18 Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, 2009). Descriptive statistics were used to summarise and describe the data, t-tests were performed to determine whether continuous, parametric data differed and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used as the non-parametric equivalent. χ 2 Were performed to determine if differences exist between groups for categorical variables. Paired t-tests were used to determine if the means of repeated measures differed significantly. Further description of the statistics employed in each study is available in each of the published manuscripts.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and ethical approval was granted at each for each of the study centres.

Results

Description of participants and follow-up

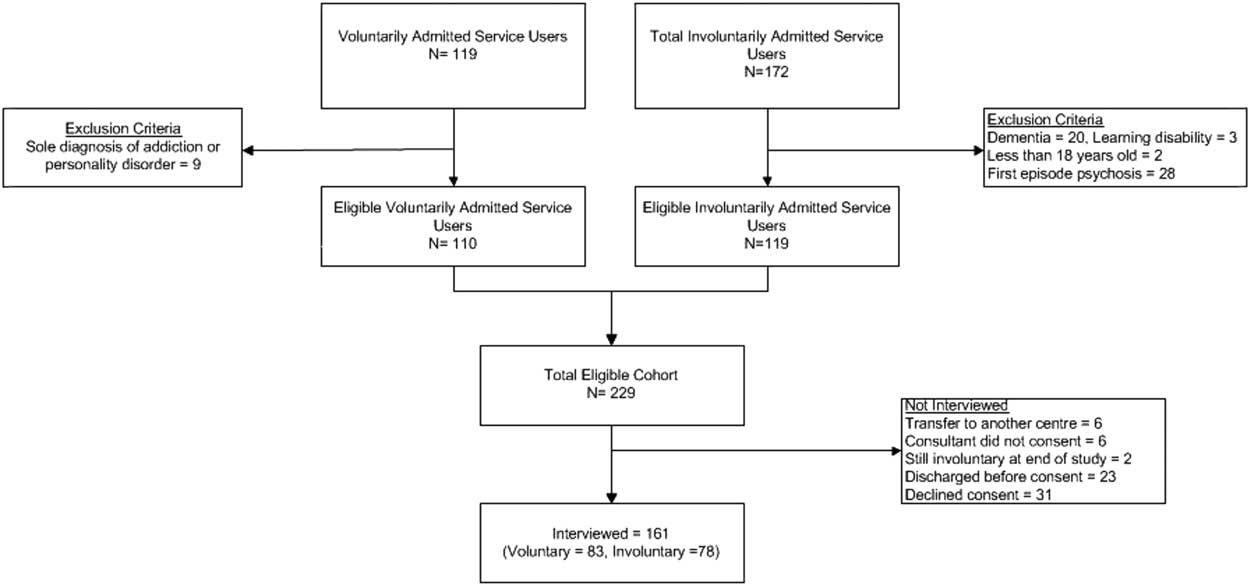

A total of 229 service users were eligible to participate in the study, of whom, 70% (n=161) consented to participate and were interviewed. A flow diagram of the recruitment and follow-up of participants is presented in Fig. 1. A description of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants is provided in Table 1. In summary, 53% were male, 63% were single and 47% had a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. The mean age was 43.7 (s.d.±13.3) years and the mean level of functioning, as determined by the GAF, was 47.1 (s.d.±11.5). Findings from the study will be presented in a descriptive manner in the subsequent sections with summaries of the statistics presented in Tables 2–4. A comparison of the level of perceived coercion, perceived pressures and procedural justice reported by the total cohort and according to legal status is presented in Table 2. The changes in functioning, quality of life, satisfaction with services and the therapeutic alliance from baseline to follow-up are presented in Table 3 and the correlations between the above factors are presented in Table 4.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of participants in the study.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total cohort and the voluntarily and involuntarily admitted service users subgroups

GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Table 2 Comparison of the level of perceived coercion, perceived pressures and procedural justice reported by in the total cohort and according to legal status

Table 3 Comparison of the therapeutic alliance, satisfaction with services, functioning and objective quality of life from baseline to follow-up

Table 4 Correlations between the experience of admission (perceived coercion, procedural justice and perceived pressures) and factors including satisfaction with services, therapeutic alliance, functioning and objective quality of life (QoL)

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Use of physical coercive measures

A total of 37% of involuntarily admitted service users experienced the use of restraint during their admission, 30% experienced seclusion and 29.4% were administered medication without consent. Overall, 42.3% of individuals admitted involuntarily experienced at least one form of physical coercion. No individual admitted voluntarily experienced physical coercion.

Perceptions of admission and coercion

Involuntarily admitted service users reported higher levels of perceived coercion, perceived pressures and lower levels of procedural justices compared with voluntarily admitted service users. Over half (59.2%) of involuntarily admitted service users reflected that their admission had been necessary.

There was no difference in the level of perceived coercion, perceived pressures, procedural justice and perceived necessity of the admission or satisfaction with services dependant on whether the interviewer was a service user research or clinician (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue, Roche, Ranieri, Shannon, Crummey, Murray, Smith, O’loughlin, Lyne, Madigan and Feeney2013). As a secondary outcome, it was found that service users were more likely to decline to participate if consent was sought by a service user researcher compared with a clinician (24% v. 8%, p=0.03).

Perceived coercion in voluntarily admitted service users

A total of 80% of service users admitted involuntarily reported experiencing at least four of the five components of the MacArthur perceived coercion scale (i.e. they had a score of 4 or greater) and therefore this level was taken to correspond to a ‘high level of perceived coercion’ (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue, Roche, Shannon, Lyne, Madigan and Feeney2014). It was found that 22% of voluntarily admitted service users experienced comparable levels of perceived coercion with that of involuntarily admitted service users (i.e. a score of 4 or greater on the MacArthur perceived coercion scale). Voluntarily admitted service users who experienced high levels of perceived coercion (‘coerced voluntary’) were more likely to have more severe psychotic symptoms, have experienced more negative pressures and perceive less procedural justice on admission. Service users who were brought to hospital under mental health legislation but who subsequently agreed to remain as a voluntary patient and those who were treated on a secure, locked ward despite being voluntary were more likely to report high levels of perceived coercion.

Caregiver’s perception of the admission experience

A total of 66 caregivers were interviewed about their relative’s admission and it was found that caregivers perceived the admission overall more positively than service users (Ranieri et al. Reference Ranieri, Madigan, Roche, Bainbridge, Mcguinness, Tierney, Feeney, Hallahan, Mcdonald and O’Donoghue2015). Caregivers tended to perceive that their relative experienced less coercion and perceived pressures than the relative/service users reported themselves, although these were significantly different only for those who were admitted involuntarily. Caregivers perceived that their relative was treated more fairly and that their admission was more ‘procedurally just’ compared with what their relative/service user reported. Interestingly, only 50% of service users provided consent for their caregivers or relative to be interviewed, demonstrating the reluctance of service users for their caregivers to be involved in research.

Satisfaction with services and therapeutic alliance

The SUPA study evaluated the therapeutic relationship and treatment satisfaction in those who were admitted voluntarily or involuntarily to hospital (Roche et al. Reference Roche, Madigan, Lyne, Feeney and O’Donoghue2014; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Roche, O’Loughlin, Brennan, Madigan, Lyne, Feeney and O’Donoghue2014). Service users who were admitted involuntarily reported a poorer therapeutic relationship, as measured by the Working Alliance Inventory, with their treating consultant psychiatrist and involuntarily admitted service users with low insight reported the poorest therapeutic relationship. In addition, the study found, somewhat unexpectedly, that the therapeutic relationship had no significant association with the level of perceived coercion, however, it was moderately associated with procedural justice. That is, higher ratings of the therapeutic relationship were significantly associated with the belief that the admission process was fair and justified, but un-related to whether or not the individual perceived the admission process to have been coercive.

Service users reported good overall levels of satisfaction with services, measured by the CSQ-8, with the subgroup of voluntarily admitted service users reporting greater satisfaction than involuntarily admitted service users. The level of satisfaction with treatment was only weakly associated with the level of perceived coercion but moderately associated with procedural justice. Overall, a better therapeutic relationship and having not been secluded during the admission were the two strongest factors in predicting higher levels of treatment satisfaction.

Quality of life and functioning at 1 year after discharge

At 1 year following discharge, 70% of individuals experienced an improvement in their level of functioning (Shannon et al. Reference Shannon, Roche, Madigan, Renwick, Dolan, Devitt, Feeney, Murphy and O’Donoghue2015). An improvement in functioning was associated with a higher number of accumulated coercive events during the admission; however, this association became non-significant when controlled for other factors associated with functioning, such as quality of life and severity of symptoms. The level of accumulated coercive events was not associated with either subjective or objective quality of life at 1 year following discharge.

Engagement with services 1 year after discharge

Hospital admission tends to address the acute needs of the service user; however, the majority of services are delivered in the community. It could be hypothesised that the experience of hospital admission could influence whether a service user engages with the service following discharge. To evaluate this, the level of engagement at 1 year following discharge was compared amongst the three groups previously described (involuntary, ‘coerced voluntary’ and ‘uncoerced voluntary’) (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue, Roche, Shannon, Creed, Lyne, Madigan and Feeney2015). A total of 94 participants were interviewed at 1 year following discharge, reflecting a follow-up rate of 58.4%. No difference in the level of engagement was found between the three groups and there was also no difference in the components of engagement that were measured; specifically, availability; collaboration; help seeking and adherence.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This review collates the findings of a project examining the perceptions of coercion by service users and the association between the experiences of coercion and outcome measures. Over half of involuntarily admitted service users reflected that their involuntary admission had been necessary and a minority of voluntarily admitted service users reported levels of perceived coercion comparable with that of involuntarily admitted service users. The level of procedural justice perceived by the service user was moderately associated with satisfaction with services and the therapeutic relationship, more so than the level of perceived coercion. The accumulated level of coercion experienced during the in-patient admission did not appear to influence outcomes such as functioning and quality of life 1 year following discharge.

Comparison of findings with previous literature

At the time of the design of the SUPA study, there was a relative paucity of research on coercion; however, in the last 5 years the research in this area has grown substantially. This is due, in part, to the EUNOMIA study; a European wide study that examined rates of coercion, associated factors and outcomes (Fiorillo et al. Reference Fiorillo, De Rose, Del Vecchio, Jurjanz, Schnall, Onchev, Alexiev, Raboch, Kalisova, Mastrogianni, Georgiadou, Solomon, Dembinskas, Raskauskas, Nawka, Nawka, Kiejna, Hadrys, Torres-Gonzales, Mayoral, Bjorkdahl, Kjellin, Priebe, Maj and Kallert2011). In addition, a number of research groups, including a service user research group, conducted similar studies and allows the findings of the SUPA study to be placed in an international context.

Rose et al. (Reference Rose, Leese, Oliver, Sidhu, Bennewith, Priebe and Wykes2011) conducted a study examining whether service users disclose different perspectives on their admission depending on the discipline of the interviewer. Service users were interviewed during their first week of admission by either a disclosing service user researcher, non-disclosing service user researcher or non-service user researcher. Participants were not randomised and were allocated sequentially to the different interviewers. Similar to the SUPA study, no difference was found in the level of perceived coercion reported by the service user according to the discipline of the interviewer. This is an important finding, as previous research has indicated that a majority of service users can report positive perspectives on their involuntary admission retrospectively (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Glockner, Dembinskas, Fiorillo, Karastergiou, Kiejna, Kjellin, Nawka, Onchev, Raboch, Schuetzwohl, Solomon, Torres-Gonzalez, Wang and Kallert2010) and the findings of Rose et al. and the SUPA study, can conclude at least that this is not due to a reporting bias. Furthermore, it means that the results of studies conducted by clinicians and service-user researchers could potentially be combined, for example, for meta-analyses.

A further important finding of the SUPA study was that approximately one in five voluntarily admitted service users reported levels of perceived coercion comparable with that of involuntarily admitted service users. It is now well recognised that legal status is not synonymous with the level of coercion experienced and more is being learnt about the ‘coerced voluntary’ group. Katsakou et al. (Reference Katsakou, Marougka, Garabette, Rost, Yeeles and Priebe2011) identified that over one-third of voluntarily admitted service users felt coerced into hospital (using a cut-off of 3 on the MacArthur perceived coercion scale) and undertook qualitative interviews with 36 of these service users (Katsakou et al. Reference Katsakou, Marougka, Garabette, Rost, Yeeles and Priebe2011). A number of themes associated with high levels of perceived coercion emerged, including service users viewing the admission and treatments as ineffective not participating in the admission and not feeling respected. A review of this literature concluded that fear of involuntary admission on behalf of the service user is perceived as a key source of coercion (Prebble et al. Reference Prebble, Thom and Hudson2014). The review concluded that the limited research conducted to date on this ‘coerced voluntary’ group raises important ethical and legal issues that should be the focus for future research.

The therapeutic relationship emerged as a central factor for service users influencing their level of satisfaction with services; an important outcome measure. Interestingly, the therapeutic relationship appeared to be a stronger predictor than the level of coercion experienced by the service user. However, this finding is not fully consistent with the international literature, as two previous studies found that the level of perceived coercion was associated with the therapeutic relationship (Sheehan & Burns, Reference Sheehan and Burns2011; Theodoridou et al. Reference Theodoridou, Schlatter, Ajdacic, Rossler and Jager2012). It could be argued that these are more conceivable results, as it is understandable that exposure to practices that are perceived as coercive could negatively impact the longer term therapeutic relationship. Yet, the findings from the SUPA study demonstrate that this is not inevitable and it is possible that the therapeutic relationship can be preserved. The identification of factors that preserve, or even strengthen, the therapeutic relationship following an episode of coercion (that was deemed unavoidable) should also be a focus for future research.

The SUPA study found that caregivers tended to underestimate the level of coercion that their relative perceived at the time of admission compared with the service user’s account. These findings are broadly consistent with that of previous studies: Giacco et al. (2012) as part of the EUNOMIA study found that caregivers perception of the involuntary admission process was more positive compared with service users. An older study also indicated that caregivers perceived their relative’s admission as less coercive and more procedurally just than the service users (Hoge et al. Reference Hoge, Lidz, Eisenberg, Monahan, Bennett, Gardner, Mulvey and Roth1998). These discrepancies of perspectives could lead to future tensions between service users and their caregivers, as it may lead to a lack of understanding of why service users could be reluctant to be readmitted.

Future research

In addition to the areas suggested above as future foci for research, there are a number of key areas that could be addressed. The majority of research to date has been descriptive and observational and while this has delivered important insights and associations, the focus should now be on interventional studies.

Interventions to improve the level of procedural justice at the time of admission could be developed, as this has been demonstrated to be a key factor influencing longer term factors such as the therapeutic relationship and the level of engagement. However, the improvement of procedural justice is challenging, as the first experience in the admission process determines the level of procedural justice perceived (Cascardi et al. Reference Cascardi, Poythress and Hall2000) and often it is non-mental health clinicians with whom service users have the first contact, such as the police or emergency department staff (McKenna et al. Reference McKenna, Simpson and Coverdale2000). Therefore, improvements in the admission experience would have to incorporate a number of disciplines.

The ‘coerced voluntary’ group should also be a focus for future research. At present, it is not known what is the most ethical and appropriate course of action; the dilemma is that the use of persuasion or ‘treatment pressures’ could avoid an involuntary admission but this action denies the service user the protective provisions under MHA legislation, such as an independent review. On the other hand, the use of an involuntary admission is a more restrictive practice and is associated with poorer outcomes. It might be possible to trial interventions in this group specifically targeting voluntarily admitted service users admitted to secure wards or those who are informed that if they attempt to leave hospital, they will be detained under mental health legislation.

Finally, the provision of psychoeducation for caregivers for individuals with a first episode of psychosis has been demonstrated to reduce relapse rates and admission rates for the service user (Bird et al. Reference Bird, Premkumar, Kendall, Whittington, Mitchell and Kuipers2010). Therefore, it is plausible that psychoeducation or another intervention directed at caregivers of individuals admitted involuntarily could reduce involuntary readmission rates, yet to our knowledge, such a trial has not yet been performed.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study are that it included a large, representative cohort of individuals admitted from three community mental health services. An additional strength is the inclusion of individuals admitted voluntarily, a group often neglected in research examining perceived coercion. However, the findings must be considered within the limitations of the study. The exclusion of individuals with a first episode of psychosis, due to their involvement in a different study, reduces the representativeness of the cohort. Furthermore, the moderate follow-up rate may have also introduced a selection bias, as service users who subsequently disengaged may not have participated in the follow-up interview. Finally, the low consent rate of service users to permit their caregivers to be contacted may have also introduced a bias.

Conclusions

The SUPA study has provided valuable insights into the perceptions of coercion of service users admitted both voluntarily and involuntarily. The study can help inform future interventional studies aimed at reducing coercion in mental health services, which may impact positively on outcomes for service users.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Professor Colm McDonald, Dr Brian Hallahan, Dr Emma Bainbridge and David McGuiness from the Clinical Science Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway who collaborated on the caregiver study. Stephen Shannon, Veronica Ranieri, Damian Smith, Kieran O’Loughlin, Ciaran Crummey and Darach Murphy for conducting interviews for this study. The authors are grateful to Karen Cobbe for her administrative work during the project. The authors are also grateful to the clinical directors of the services for supporting the study: Dr Siobhan Barry, Dr Justin Brophy and Dr Anthony McCarthy.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Financial Support

This study was partially funded by a grant from the Mental Health Commission (no grant number).