Article contents

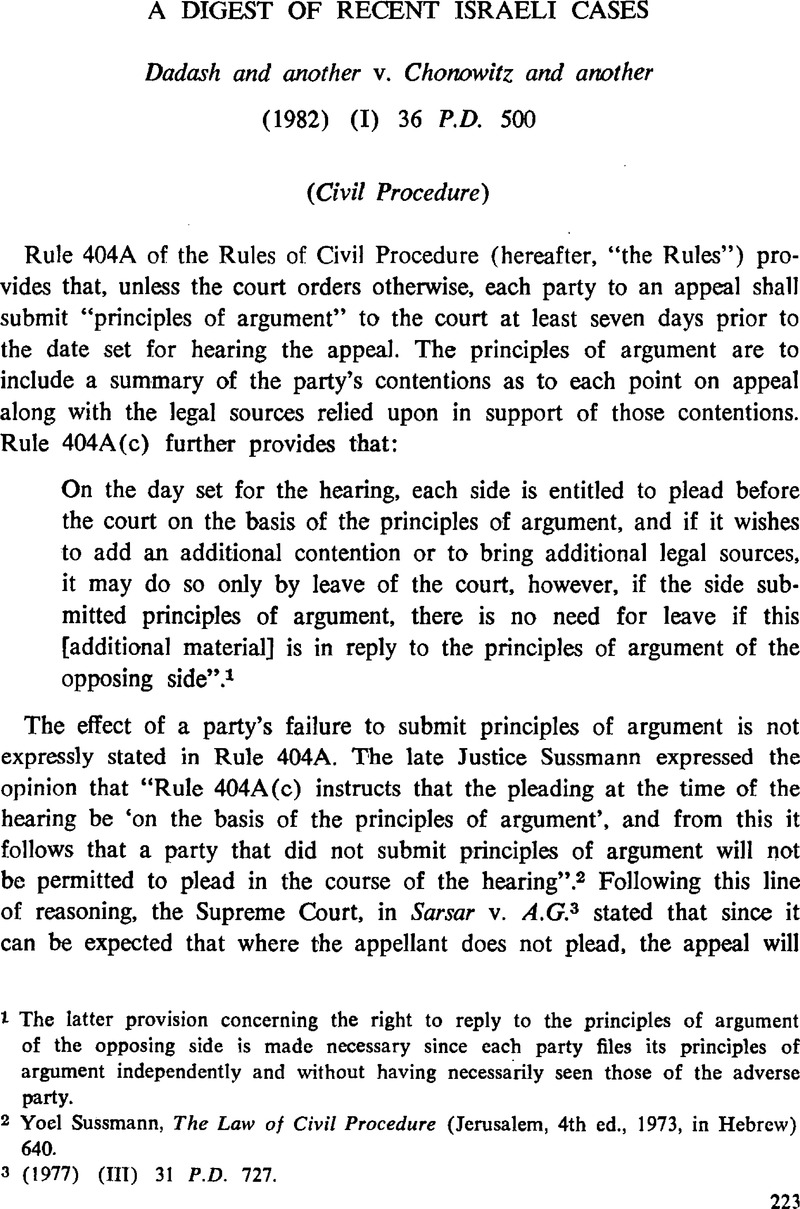

A Digest of Recent Israeli Cases

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press and The Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1982

References

page 223 note 1 The latter provision concerning the right to reply to the principles of argument of the opposing side is made necessary since each party files its principles of argument independently and without having necessarily seen those of the adverse party.

page 223 note 2 Sussmann, Yoel, The Law of Civil Procedure (Jerusalem, 4th ed., 1973, in Hebrew) 640.Google Scholar

page 223 note 3 (1977) (III) 31 P.D. 727.

page 224 note 4 (1981) (III) 35 P.D. 527.

page 224 note 5 D. Levin J., concurring, stressed the importance of submitting principles of argument reiterated the note of caution expressed by S. Levin J. in Lehem. However, Landau P., concurring, stated that opposed to the dangers inherent in permitting parties to plead absent principles of argument, stood the consideration that the court should not close its doors to the adjudication of a conflict on the merits, as a result of a mistake made by a party or his counsel in a matter of procedure.

page 225 note 6 Rule 408: “Concerning appearance on the date set for the hearing of an appeal or an adjourned hearing, the court shall act thus:

(1) …

(2) …

(3) Where the respondent appeared, and the appellant failed to appear after receiving notice of the date of the hearing, the appeal shall be heard, or dismissed without prejudice, or adjourned, as the court shall decide”.

page 226 note 1 Eavesdropping Law, 1979: 6. (a) The President of a District Court or, in his absence, a Relieving President of a District Court, may, on the application of a competent police officer, by order, permit eavesdropping if he is satisfied that it is necessary so to do to prevent offences or detect offenders.

(b) …

(c) If the Judge refuses to grant the permit applied for, the Attorney General or his representative may appeal to the President of the Supreme Court or to a Judge of the Supreme Court appointed for this purpose by the President thereof”.

page 226 note 2 A complete translation of the law appears in (1980) 15 Is.L.R. 150.

page 226 note 3 Evidence Ordinance (New Version), 1971: “48. (a) An advocate is not bound to submit as evidence any matters or documents which have passed between hint and his client or a person acting on behalf of his client and which are substantively connected with the professional service rendered by him to his client, unless the client has waived the privilege. The same applies to an advocate's employee whom any matters or documents communicated to the advocate reached during his work in the service of the advocate”. (2 L.S.I. [N.V.] 209).

page 226 note 4 Supra n. 1.

page 226 note 5 Abuhatzeira v. State of Israel (1981) (III) 35 P.D. 681, 692. In this case a lawyer testified as to an attempt to solicit him to commit perjury. The defence urged that the testimony was inadmissible pursuant to sec. 48 of the Evidence Ordinance and sec. 90 of the Chamber of Advocates Law, 1961 (5 L.S.I. 196). The Supreme Court ruled, per Beisky J., that not all communications between a lawyer and client are privileged, stating: “No one would imagine—and I find flaw in the very assertion—that such matters bear a substantive connection to the professional service rendered by a lawyer to his client… this is exclusively a criminal matter, far, far away from what the legislator intended to protect by granting privilege between a client and a lawyer and his employees”. Cf. Clark v. States of Texas, 159 Tex. Crim. 187, 261 S.W.2d 339, certiorari denied 74 S. Ct. 69, 344 U.S. 855, holding that a lawyer's advice to his client to dispose of evidence is not privileged, and Clark v. United States 289 U.S.1, (at 15), 77 L. Ed. 993, 53 S. Ct. 465, 469 per Cardozo J.: “There is a privilege protecting communications between attorney and client. The privilege takes flight if the relation is abused…” and see generally: Am. Jur. 2d, Witnesses s. 207 et seq.

page 227 note 6 Cf. 18 U.S.C.A. s. 2517 (4) : “No otherwise privileged wire or oral communication intercepted in accordance with, or in violation of, the provisions of this chapter shall lose its privileged character”, and cf. 50 U.S.C.A. s. 1806.

page 227 note 7 Cf. Standards Relating to Electronic Surveillance (A.B.A., 1971) Approved Draft, 1971, sees. 5.10–5.11, and see, generally, commentary in Tentative Draft, 1968, pp. 152–158.

page 228 note 1 Road Accident Victims Compensation Law, 1975 (29 L.S.I. 311):

Chapter One: Interpretation

Definitions. 1. In this Law—

“road accident” means an occurrence in which bodily damage is caused to a person in consequence of the use of a motor vehicle, whether while the same is moving or stationary; “bodily damage” means death, illness, injury or a physical, psychological or intellectual defect;

“victim” means a person to whom bodily damage has been caused in a road accident; “the Insurance Ordinance” means the Motor Vehicle Insurance (Third-Party Risks) Ordinance (New Version) 5730—1970; “insurer” has the same meaning as in the Insurance Ordinance and includes a person exempt from the duty of insurance under sections 4 to 6 thereof;

“motor vehicle” or “vehicle” means a vehicle propelled by mechanical power and includes a motor bicycle with a side-car, a motor tricycle, a bicycle or tricycle assisted by a motor, and a vehicle drawn or supported by a motor vehicle.

Chapter Two: Liability

Liability of 2. driver of vehicle. (a) A person using a motor vehicle (hereinafter referred to as “the driver”) shall compensate a victim for bodily damage caused to him in a road accident in which the vehicle was involved.

(b) Where the vehicle was used with the permission of the owner or possessor, liability shall also be incurred by the person who permitted its use.

(c) The liability is absolute and entire and it shall be im material whether or not there was fault on the part of the driver and whether or not there was fault or contributory fault on the part of others.

Remedy for 4. bodily damage. (a) The provisions of sections 19 to 22, 76 to 83, 86, 88 and 89 of the Civil Wrongs Ordinance (New Version) (herein-after referred to as “the Civil Wrongs Ordinance”) shall apply to the right of a victim to compensation for bodily damage, but…

page 229 note 2 ibid.:

Exclusivity 8. of cause of action. (a) A person whom a road accident has vested with a cause of action under this Law, including an insurance claim under section 3(a)(2) of the Insurance Ordinance, shall not have a cause of action for bodily damage under the Civil Wrongs Ordinance unless the accident was caused intentionally by another person.

(b) The provision of subsection (a) shall not derogate from a claim under the Civil Wrongs Ordinance by a person who has no cause of action under this Law.

page 229 note 3 (1979) (II) P.M. 181.

page 229 note 4 (1981) (I) P.M. 214.

page 230 note 5 Supra n. 1.

page 230 note 6 Civil Wrongs Ordinance (New Version), (2 L.S.I. [N.V.] 5) Sec. 76: Compensation may be awarded either alone, or in addition to or in substitution for, an injunction: Provided that—

(1) Where the plaintiff has suffered damage, compensation shall only be awarded in respect of such damage as would naturally arise in the usual course of things and which directly arose from the defendants civil wrong;…

page 230 note 7 Supra n. 1.

page 231 note 8 Englard, I., Road Accident Victim Compensation (Jerusalem, 1978, in Hebrew), 14.Google Scholar

page 231 note 9 Cf. Englard at p. 15: “The general condition of entitlement is composed of two premises: the use of a motor vehicle and the causing of the damage in consequence of the use. The first refers to activity related to the purpose of the vehicle, the other is related to the causal connection between the activity and the damage inourred by the injured party”.

page 232 note 10 (1981) (III) 35 P.D. 197.

page 232 note 11 Op. cit., at 204 and cf. Yanis v. Texaco, Inc. (1975) 375 N.Y.S. 2d 570, at 572: “Any on-going activity relating to the vehicle, which is in conformity with its normally intended purpose, should constitute a ‘use’ of such vehicle…“

page 232 note 12 Op. cit., at 210.

page 232 note 13 Englard, at 19.

page 232 note 14 Supra n. 10.

page 232 note 15 Road Accident Victims Compensation Law (Amendment no. 4); 5741–1981, H.H. 453.

page 233 note 16 Cf. Englard, at 32: “However, it should be emphasized that this section [76] of the Civil Wrongs Ordinance concerns the extent of the liability and not the question of its existence. In the framework of the Road Accident Victims Compensation Law the section will therefore apply after it has been determined that there was a road accident as defined in the law…section 76 will, therefore, be of significance in cases in which the original damage is aggravated as a result of later causes, such as medical negligence…”.

page 233 note 17 S.H. 163.

- 1

- Cited by