Introduction

In January 2021, a group of people stormed the United States Capitol in Washington DC, in a clumsy and theatrical attempt to overturn Donald Trump's electoral defeat. Some of the demonstrators vandalized and looted the building, before being evacuated by the police. The clashes resulted in five deaths. According to the press, among the people participating in the demonstration, there were many believers of ‘QAnon’, a conspiracy theory about American politics, whose network of adherents contributed to organizing the protest (Biesecker et al., Reference Biesecker, Kunzelman, Flaccus and Mustian2021; Kuznia et al., Reference Kuznia, Devine, Bronstein and Ortega2021). Less than 2 years earlier, in May 2019, the Phoenix Field Office of the FBI released an ‘Intelligence Bulletin’ memo entitled ‘Anti-Government, Identity Based, and Fringe Political Conspiracy Theories Very Likely Motivate Some Domestic Extremists to Commit Criminal, Sometimes Violent Activity’, which lists a number of cases reported from different law enforcement agencies where individuals committed or planned violent crimes (including multiple homicides) motivating their actions with known political conspiracy theories such as the ‘Zionist Occupation Government’, ‘Pizzagate’, the ‘New World Order’, ‘HAARP’, as well as QAnon itself.Footnote 1

As of 2021, there is no doubt that conspiracy theories can have important political implications. Research in Europe and in the US shows that belief in conspiracies is associated with political support, ideological identity and populist attitudes (see Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Walter and Drochon, Reference Walter and Drochon2020). However, as the two examples above illustrate, the correlates of conspiracy belief may go well beyond electoral support and opinions, concerning the modes of political action as well: specifically, conspiracy theories may be associated with violent behaviors and attitudes. In part, this can be related to a change in the way citizens participate in politics. While electoral participation is declining in many industrialized countries, contentious politics is on the rise (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012; Blais and Rubenson, Reference Blais and Rubenson2013). As a recent report shows, from 2009 to 2019, anti-government protest events increased on average about 12% every year in Europe, and 17% in North America (Brannen et al., Reference Brannen, Stirling Haig and Schmidt2020). In other words, politics worldwide is becoming more physical: democratic citizens are relying more and more on alternative forms of participation, often not peaceful, to make their political point. In this scenario, communities of conspiracy believers might play a role in mobilizing the citizens. For instance, more than half of QAnon-related accounts on Twitter mentioned the date of the Capitol Hill riots in the days ahead of the event, suggesting an active role in organizing the demonstration (Lytvynenko and Hensley-Clancy, Reference Lytvynenko and Hensley-Clancy2021). However, this does not account for all the cases in which individuals commit violent crimes motivated by conspiracy theories. The question remains what is the nature of the link between conspiracy beliefs and political violence – whether springing from protest events or not. Do networks of conspiracy adherents merely provide an infrastructure for the organization of violent events? Or is there something in the narrative promoted by conspiracy theories that triggers violence?

In this article, we investigate the association between belief in conspiracies and endorsement of political violence. We propose that conspiracy narratives are part of a worldview that sees the official political institutions as the ultimate scapegoat for societal problems. By constructing a system of mutually-reinforcing beliefs about the (dishonest) nature and the (malevolent) aims of the forces that regulate politics and society, conspiracy theories provide a foundation for a worldview that fuels people's animosity toward the institutions, the procedures, and the actors that are central to representative democracies. Some existing studies suggest that believing in conspiracy theories promotes political action (Imhof and Bruder, Reference Imhoff and Bruder2014; Kim Reference Kim2019), others that it suppresses it (Jolley and Douglas, Reference Jolley and Douglas2014), and others that it bolsters only non-normative forms of participation (like refusing to pay taxes, see Imhoff et al., Reference Imhoff, Dieterle and Lamberty2021). The focus of this study is on the support of specifically violent means to convey political messages.

Building on ‘pathway’ theories of radicalization, we propose a model in which conspiracy theories channel individuals' resentments toward political goals, making them more likely to support the use of violence for political purposes. By using this theoretical background, we do not mean to lump together political protest and terrorism (as the latter is the main focus of research on radicalization). Reasons to protest are often legitimate, and violent outbursts can be an inevitable outcome in cases when protests are repressed, or protesters' demands are systematically ignored. However, we do not claim to provide an explanation for people's use of violence in political protests. We rather focus on people's attitudes toward violent acts, noting that they often are a middle step in the process of individual radicalization (see McCauley and Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2008; King and Taylor, Reference King and Taylor2011; Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014). In the empirical part of the article, we provide some evidence of the association between belief in conspiracies and endorsement of political violence using data collected from Amazon Mechanical Turk in the US in March 2014.

Belief in conspiracy theories

Definitions of conspiracy theories in the literature are multiple, and vary according to the focus of the studies defining them. Here we take up Byford's (Reference Byford2011) conceptualization, and define the conspiracy theory as a narrative, an account of observed events that is characterized by some specific characteristics. First, it is based on the assumption that observable facts are the product of deliberate actions of a group of people, regardless of how complex their realization may appear. Such a monistic and intrinsically deterministic view assigns immense power and control to an invisible elite whose purposes are the true driving forces behind all political events (Keeley, Reference Keeley1999; Clarke, Reference Clarke2002). Second, because of the almightiness and secrecy of the actors to which they attribute the cause of all things, conspiracy theories are in fact unfalsifiable. Any piece of evidence disconfirming them, or any lack of evidence supporting them, will be interpreted by the believers as a proof of the hidden power of the conspirators, hence becoming an integrating part of the narrative (Keeley, Reference Keeley1999). Thus, conspiracy theories differ from other types of accounts (including scientific explanations) in their systematic exclusion of alternative, non-conspiratorial explanations, even in the face of evidence or greater plausibility (Aaronovitch, Reference Aaronovitch2009).

Believing in conspiracy theories implies endorsing a specific mindset, as it would be to subscribe to a certain ideology. Ideological thinking implies a certain amount of constraint in the positions taken on single political issues (see Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964), and belief in different conspiracies also appears to be remarkably consistent. As Goertzel (Reference Goertzel1994) suggests, different conspiracy narratives are often used to provide mutually-reinforcing evidence in support of one another. Moreover, one of the best empirical predictors of a person's belief in one conspiracy is the fact that s/he believes in other conspiracies. Empirical studies show that this pattern applies even when people are asked about fictitious conspiracies (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Coles, Stieger, Pietschnig, Furnham, Rehim and Voracek2011) or when the stories clearly contradict each other: in a survey study conducted by Wood et al. (Reference Wood, Douglas and Sutton2012), respondents who believed that Princess Diana was murdered were also more likely to believe that she had faked her own death. This suggests that people do not necessarily evaluate the content of every single conspiracy theory on its own merits, but they buy the full package instead (Brotherton et al., Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013). In other words, conspiracy theories collectively form a system of mutually-reinforcing beliefs that conform to the same narrative about the processes regulating political events.

But what is the content of this narrative? A recurring theme in conspiracy theories is that the decisional power and control over the mechanisms that regulate the political world are held by elites typically driven by cynical purposes, in collusion with other public institutions. Wood et al. call this narrative ‘deceptive officialdom’, that is, ‘the idea that authorities are engaged in motivated deception’ (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Douglas and Sutton2012: 768). This view is reinforced by studies showing a significant association between conspiracy belief, political cynicism, and negative attitudes toward the authority (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Coles, Stieger, Pietschnig, Furnham, Rehim and Voracek2011).Footnote 2

What are the factors making some individuals more likely to buy into conspiracy narratives than others? Research in this domain is vast, however some common threads can be identified. Early explanations have regarded conspiracy belief as a form of collective paranoia. According to Hofstadter (Reference Hofstadter1965), one of the central aspects of conspiratorial narratives is the ‘feeling of persecution’ that they entail. However, whereas paranoia is a clinical condition affecting individuals, conspiracy theories imply a collective dimension that separates them from individual delusions (Zonis and Joseph, Reference Zonis and Joseph1994; Bale, Reference Bale2007; Byford, Reference Byford2011). While people suffering from paranoia tend to see hostile plots perpetrated against themselves, conspiracy theory believers typically describe machinations against their own group (Bartlett and Miller, Reference Bartlett and Miller2010; Sapountzis and Condor, Reference Sapountzis and Condor2013).Footnote 3 The collective dimension of conspiracy belief has been emphasized by recent political behavioral research, which found an empirical association with factors reflecting a group-centered mindset, such as partisanship (Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014), political extremism (van Prooijen et al., Reference Van Prooijen, Krouwel and Pollet2015), and populism (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017).

Researchers have been looking also at the association between conspiracy belief and different dispositional traits and cognitive styles. For instance, some traits that are strongly connected to conspiracy belief are the tendency to make causal attributions of phenomena to hidden forces, and a preference for Manichean narratives (Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014). Consistently, studies found significant correlations between belief in conspiracies and belief in paranormal or supernatural forces (Brotherton et al., Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013; Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Heffke, Neave, Nouripanah and Imhoff2013). Researchers have also focused on the impact of Big Five personality traits on individual differences in conspiracy belief. Empirical findings suggested a negative correlation between belief in conspiracies and agreeableness (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham2010, Reference Swami, Coles, Stieger, Pietschnig, Furnham, Rehim and Voracek2011; Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Heffke, Neave, Nouripanah and Imhoff2013) and a positive association with openness to experience (Swami et al., Reference Swami, Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham2010), although other studies could not replicate the same results, suggesting that the relationship between personality on conspiracy belief is somewhat complex and possibly mediated by neglected factors (Brotherton et al., Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013).

Finally, and importantly, belief in conspiracy theories is associated with different factors signaling a lack of personal significance. According to Kruglanski et al., individuals experience loss of significance (defined as the ‘fundamental desire to matter, to be someone, to have respect’, Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014: 73) when they experience failure, humiliation, or other negative or traumatic circumstances to which they or their group are exposed (see also Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Jasko, Webber, Chernikova and Molinario2018). Such experiences may trigger feelings of powerlessness and resentment, which have been found to relate to belief in conspiracies. Uscinski and Parent (Reference Uscinski and Parent2014) show that conspiracy theories flourish among ‘political losers’, that is, among people who are subdued in a power asymmetry, like Republican supporters under a Democratic president and vice versa. In the very first study on conspiracy theories in American politics, Hofstadter (Reference Hofstadter1965) argues that a ‘paranoid’ outlook to politics is more likely to occur among people who feel powerless because systematically excluded from political decision making (see Abalakina-Paap et al., Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Gregory1999). Such feelings of deprivation and impotence can turn into resentment and hostility against the individuals or groups that are perceived to be the culprit. As Moscovici (Reference Moscovici, Graumann and Moscovici1987) points out ‘[w]hoever feels deprived of something instinctively looks for a cause of the deprivation’, and conspiracy narratives easily offer a scapegoat for that. Likewise, Robins and Post (Reference Robins and Post1997) argue that paranoia (which they define as a ‘political disease’) prompts individuals to project their own hostility outwards, effectively helping those who suffer from it maintain high self-esteem. Imhoff and Bruder (Reference Imhoff and Bruder2014) argue that conspiracy thinking simplifies complex issues by offering a target to blame, and in doing so they may help members of disadvantaged groups feel empowered. These intuitions have been corroborated by empirical studies showing that conspiracy belief is related to indicators such as powerlessness, external locus of control, low self-esteem, uncertainty, anomie, low interpersonal trust, and hostility (Goertzel, Reference Goertzel1994; Abalakina-Paap et al., Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Gregory1999; Grzesiak-Feldman and Irzycka, Reference Grzesiak-Feldman and Irzycka2009; Van Prooijen and Jostmann, Reference Van Prooijen and Jostmann2013). This point is important because loss of significance is thought to provide the motivational basis for personal enhancement through radical actions (see Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Bélanger, Gelfand, Gunaratna, Hettiarachchi, Reinares, Orehek, Sasota and Sharvit2013, Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014).

Conspiracy theories in the pathway to radicalization

Research on radicalization mostly focuses on forms of violent extremism, such as terrorism (Moghaddam, Reference Moghaddam2005; Wilner and Dubouloz, Reference Wilner and Dubouloz2010; Borum, Reference Borum2011; King and Taylor, Reference King and Taylor2011; McCauley and Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2011; Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014). In virtually all recent accounts, radicalization is conceptualized as a process, or a pathway, that starts with common citizens and ends with individuals who are willing to take many lives, sometimes including their own, to pursue a political ideal. For instance, according to a recently proposed pathway model called ‘Significance Quest Theory’ (e.g. Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Jasko, Webber, Chernikova and Molinario2018), all individuals share a need for personal significance, which may be frustrated as a consequence of humiliating or traumatic circumstances. When this happens, people tend to enact behaviors to restore their sense of purpose. While they are on this path, they might encounter a narrative that helps them making sense of how the world works, and what goals are worth pursuing to affirm themselves. These narratives can be provided by religion or other ideologies. Conspiracy theories surely provide an explanation of how the world works, and while they do not propose violence as a solution, they do tend to create communities of people who share the same worldview and goals. The presence of such networks is another factor that can contribute to radicalization.

While enacting violence is the extreme outcome of this process, the acceptance of violence is regarded as a middle step in the path of individual radicalization. As Kruglanski et al. argue, radical behavior is a means to reach a focal goal (such as e.g. making a political statement), which coexists with other alternative goals (e.g. going about everyday life). The more the focal goal is important, to the detriment of alternative goals (quite literally, as it can even overshadow the goal to survive), the greater is the degree of radicalization (Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014). In this view, supporting or justifying political violence implies that the focal goal is important, but not that important to dominate other goals in a person's life. Nevertheless, the focal goal is there, and in the right circumstances, it might become so central to determine behavior. As Jackson et al. point out, ‘[p]eople who think it is morally acceptable to use violence to achieve certain goals may be more likely to engage in the act if the situation arose, less likely to condemn other people's behavior, and less likely to assist legal authorities in the detection and prosecution of violent acts’ (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Huq, Bradford and Tyler2013: 480).

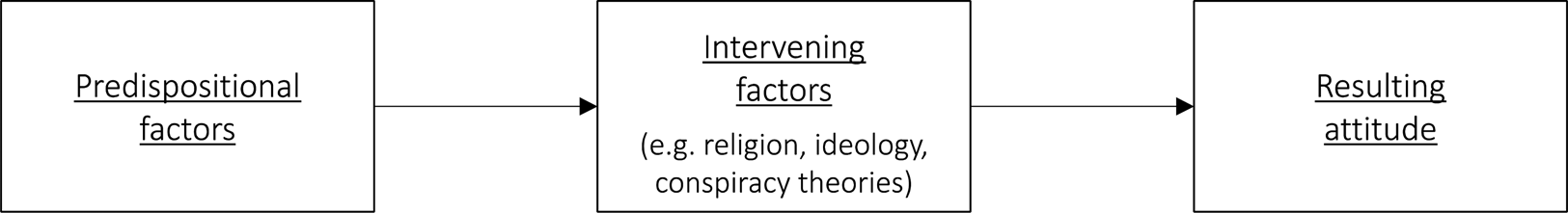

In a pathway model of the radicalization process (see e.g. King and Taylor, Reference King and Taylor2011; Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Jasko, Webber, Chernikova and Molinario2018), the path starts with a set of predispositional factors, which may stem from a person's current life conditions as well as dispositional traits, and ends with a resulting attitude or behavior. In between the two, there are one or more intervening factors, like a narrative or the active recruitment by extremist organizations, that play a crucial role in the chance of radicalization (see Figure 1). The starting point lies in a number of factors that make some individuals more likely than others to embark on a pathway toward radicalism. Interestingly, many common factors have been identified independently by research on radicalization and conspiracy theory beliefs. Most of them revolve around the presence of an individual crisis, or again, loss of significance (Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014). While research on terrorism usually focuses on relative deprivation, moral outrage, and identity-related issues (Moghaddam, Reference Moghaddam2005; Sageman, Reference Sageman2008; Wilner and Dubouloz, Reference Wilner and Dubouloz2010; King and Taylor, Reference King and Taylor2011), research on conspiracy belief emphasizes anomie, lack of self-esteem, lack of control, uncertainty, hostility, social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism, and feelings of powerlessness as important correlates of conspiracy belief (Goertzel, Reference Goertzel1994; Abalakina-Paap et al., Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Gregory1999; Swami et al., Reference Swami, Coles, Stieger, Pietschnig, Furnham, Rehim and Voracek2011; Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Heffke, Neave, Nouripanah and Imhoff2013; Van Prooijen and Jostmann, Reference Van Prooijen and Jostmann2013). In general, a common factor that seems to be central to both literatures is a heightened sense of resentment for one's own conditions, which can result in plain hostility toward the enemy when activated. In the case of conspiracy theories, the enemies are the governing elites, which are perceived as the reason why the world, as well as one's own life, are not going in the way they should. In fact, as Abalakina-Paap et al. (1999) argue, conspiracy theories often provide an outlet for hostility and aggression. Moreover, as individuals endorsing conspiracy theories are likely to embrace populist attitudes (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017), which have been shown to build in part upon feelings of anger (Rico et al., Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017), it is reasonable to expect aggression to be a relevant factor in a path toward radicalization fueled by conspiracy theories.

Figure 1. Pathway from predispositions to attitudes.

Once a predisposition is there, the presence of intervening factors that point the individual toward radicalism is a crucial element. In the case of research on homegrown terrorism, which is typically focused on members of Muslim minorities in Western countries, two important sources are religion and established extremist organizations. In the case of research on conspiracy belief, the emphasis is on the monistic causal explanations offered by many conspiracy theories, which helps people see reality as something understandable and predictable (Van Prooijen and Jostmann, Reference Van Prooijen and Jostmann2013). Like religions, conspiracy theories offer simplified and intuitive accounts for events, often presenting them as conflicts over sacred values (Franks et al., Reference Franks, Bangerter and Bauer2013). Moreover, like religious faith, conspiracy belief defines the borders of a community (Byford, Reference Byford2011). By granting individuals a source of social self-categorization, a membership to the group of believers, both religion and conspiracy theories can provide a sense of perceived external approval, therefore and again contributing to uncertainty reduction (Hogg, Reference Hogg2000).

Scholars seem to agree that the structure of conspiracy belief resembles ideology in that beliefs in different conspiracies reinforce one another into a general monological narrative. Believing in different conspiracies does not mean that they must logically imply one another – as the study by Wood et al. (2012) cleverly shows – but that they resonate with the same underlying narrative. This narrative is that official power institutions secretly colluded with one another, and they act not in the interest of the citizens, whom they are meant to serve and/or represent, but of some secret and powerful elites. This narrative resembles the one given by many radical Muslim groups, which describes a war between the West, as a singular monolithic entity, and Islam (Sageman, Reference Sageman2008). More generally, both extremist narrations and conspiracy theories identify and point at precise enemies. In this way, they both fulfill the function of displacing individuals' resentment and aggression onto out-groups by making them scapegoats (Young, Reference Young1990; Abalakina-Paap et al., Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Gregory1999; Goertzel, Reference Goertzel1994; Moghaddam, Reference Moghaddam2005). Group dynamics play a similar role. Conspiracy believers like to be ‘in the know’, share precious non-mainstream information with other believers, and by doing so increase their own popularity in the community (Byford, Reference Byford2011). However, when group boundaries are established, they can lead to the isolation of the members, attitudinal polarization, and increasing despise for the out-groups (McCauley and Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2008). Both these factors may prompt individuals to think that political adversaries are enemies, that standard forms of political action may be not effective to defeat them, and therefore that violence is a justifiable or even necessary undertaking to bring political justice.

In sum, pathway models of radicalization emphasize the central role of narrative, whether religious or ideological, in channeling the frustration of individuals in crisis toward more or less symbolic political targets. In this framework, we find that conspiracy theories could fit right in. Research on conspiracy belief identifies several factors that explain people's susceptibility to conspiratorial narratives, many of which resemble the symptoms of significance crisis proposed in the literature on radicalization. Given these premises, an association between belief in conspiracies and the tendency to legitimize political violence is warranted. In the next sections, we offer some empirical corroboration for this association.

Empirical evidence

We provide here some empirical evidence of the association between the factors discussed above with an observational study based on individual survey data. Our main goal is to assess the association between people's belief in conspiracies and their endorsement of political violence; however, we wish to take into account also the role of some potential predispositional factors that may put individuals onto the pathway. We offer two types of empirical evidence. First, we simply show the correlation between a measure of conspiracy belief and two indicators of respondents' endorsement of political violence, as well as other variables that might be associated with either construct. Second, we run a set of regressions in which attitudes toward political violence are predicted by people's degree of conspiracy belief as well as several attitudinal, political, and socio-demographic controls.

Data and variables

We use data collected by the Political Behavior Research Group (PolBeRG) at the Central European University, with Amazon's service Mechanical Turk in March 2014. In total, 645 American citizens of voting age volunteered to participate in the survey that contains several experiments and a multitude of batteries of questions designed to tap into the demographic, psychological, sociological, and political characteristics of individuals.Footnote 4 Financial incentives were offered as rewards for decisions that the respondents made in some of the experiments, and several attention checks were included throughout the survey (see Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Meyvis and Davidenko2009), likely contributing to the quality of our data.

As for the sample composition, 52.7% of the respondents are women, the age ranges from 18 to 77, with an average of 35.7 and a median of 32, 5.7 years lower than the national median.Footnote 5 The sample is markedly more educated than a nationally representative sample, as 92% of the respondents reported having more than 12 years of formal education. Also, the sample has a noticeable skew toward the liberal side of the ideological spectrum, with 52.4% of the respondents reporting to be slightly or very liberal, and only 24.8% slightly or very conservative. Regarding race, whites are clearly oversampled, with a prevalence of 82%, while 5.5% identify as African-American, 3.8% as Hispanics, and 3.6% as Asian. We are aware that, being a convenience sample, our pool of respondents looks rather different from the US general population in 2014, at least in terms of the observable demographic characteristics reported above. This would likely produce biased assessments of the endorsement of political violence and conspiracy belief in the population if we were to present univariate results (for instance, this has been documented with respect to several clinical-psychological phenomena, see Arditte et al., Reference Arditte, Çek, Shaw and Timpano2016). However, our goal here is not to assess the prevalence of the phenomena that we observe in the general population, but rather to assess the patterns of associations between them. To do so, we include in our models all the demographic covariates discussed above, to control for sample composition. Moreover, MTurk samples have been found to provide reasonably valid estimates of correlational patterns (Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015) and treatment effects (Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015). Hence, granted that we do not wish to make general claims about the entire US population, we believe that the results of our empirical analyses can provide a useful piece of evidence with respect to the association between conspiracy belief and endorsement of political violence.

We measure respondents' attitudes toward political violence using two batteries of questions. The first is a 4 item scale by Jackson et al. (Reference Jackson, Huq, Bradford and Tyler2013) measuring people's principled ‘justification of violence’ as an adequate response to perceived injustice or unfairness (JPV). The second is a battery developed by us, called ‘Legitimate Radical Political Action’ (LRPA). It contains five items inquiring about the respondents' willingness to accept violence as a justified mean to achieve political ends. Because this is a new instrument, we report here the wording of the items.Footnote 6

1. In extreme circumstances, it is acceptable for someone in your community to physically harm a government official to express political discontent.

2. In extreme circumstances, it is acceptable for someone in your community to protest violently to express political discontent.

3. In extreme circumstances, it is acceptable for someone in your community to destroy property to express political discontent.

4. In extreme circumstances, it is acceptable for someone in your community to call for violence to express political discontent.

5. In extreme circumstances, it is acceptable for people in your community to arm and isolate themselves to express political discontent.

The other key indicator that we are interested in is the respondents' belief in conspiracies. Following Brotherton et al. (Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013), the subjects were asked to assess the veracity of 15 conspiratorial statements on topics ranging from government and global organized malevolence to extraterrestrial cover-ups. The index is made of different facets exploring different kinds of conspiratorial thinking, however since we do not expect different facets to have different effects on our outcome variables, we keep all items together in one latent construct of general conspiracy belief.

We also observe other psychological constructs that we include in our regression models as controls. We measure the respondents' level of dispositional aggression using the well-known and validated aggression scale by Buss and Perry (Reference Buss and Perry1992) comprising 28 items.Footnote 7 We include 10 items of trust in institutions, adapted from the European Social Survey. This controls for an important confounder in our analyses: the tendency to despise the political system, which might affect both the likelihood to embrace conspiracy theories and to endorse violent political actions. To be sure, this is an imperfect measure for a generalized anti-systemic attitude (which could be captured by recently-developed instruments such as the ‘need for chaos’ scale, see Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Osmundsen and Arceneaux2020); however, it well reflects the respondents' attitudes toward the actors that make the system, which are the main target of both conspiracy theories and many violent political demonstrations. We also include right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) with 19 items on a scale proposed by Altemeyer (Reference Altemeyer2007) and social dominance orientation (SDO), measured with 16 items, following Sidanius and Pratto (Reference Sidanius and Pratto2001). These two factors capture the two major facets of political ideology, and have been shown to correlate with belief in conspiracies (see Bruder et al., Reference Bruder, Heffke, Neave, Nouripanah and Imhoff2013). Finally, we include 8 items to measure the respondents' sense of internal self-efficacy (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Gully and Eden2001), or their perception of their personal ability to carry out tasks and bring about desirable outcomes. This is a rough (inverse) proxy for lack of control, a variable that has been identified in several studies as a determinant of conspiracy belief.Footnote 8

For the regression models, we also include other demographic and political controls: gender (a dummy variable taking value 1 for female respondents), education (three ordered categories: no degree, up to Bachelor's degree, and Master's degree or higher; centered around the middle category), age (standardized), race (a dummy indicating whether the respondent is not white), and ideological identity (the classic 7-point scale ranging from extremely liberal to extremely conservative, centered around 4 which indicates ‘moderate, middle of the road’).

Some of the batteries that we use in this study had to be abbreviated to keep the length of the survey within tolerable limits and avoid respondent fatigue. This was done by assigning to each respondent only a subset of all the items considered for the measurement of any given trait (see Littvay, Reference Littvay2009). However, as the selection of items assigned to each respondent was random, the system missing data can be considered completely at random. This allows an efficient handling of the missing observations via a full information maximum likelihood technique (see Enders, Reference Enders2010).Footnote 9

We extract the respondents' individual scores on the latent constructs measured by our multi-item batteries by fitting a confirmatory factor analysis model.Footnote 10 All the included items load well on the latent factors, and all batteries have good reliability, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Reliability score of 8 multi-item batteries

Correlation analysis

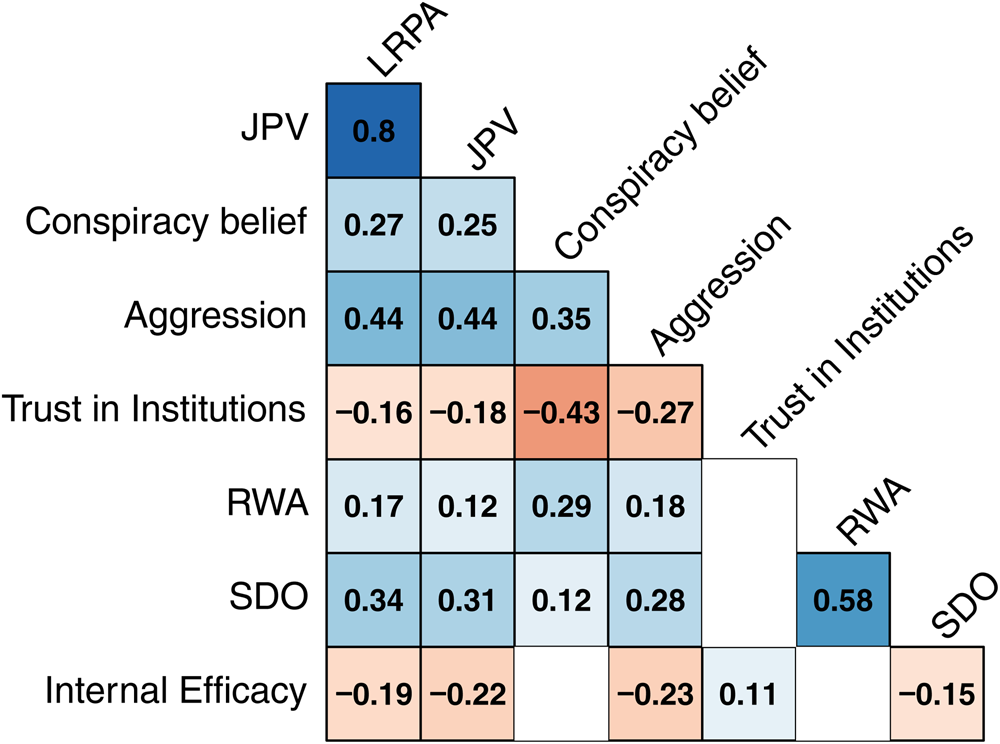

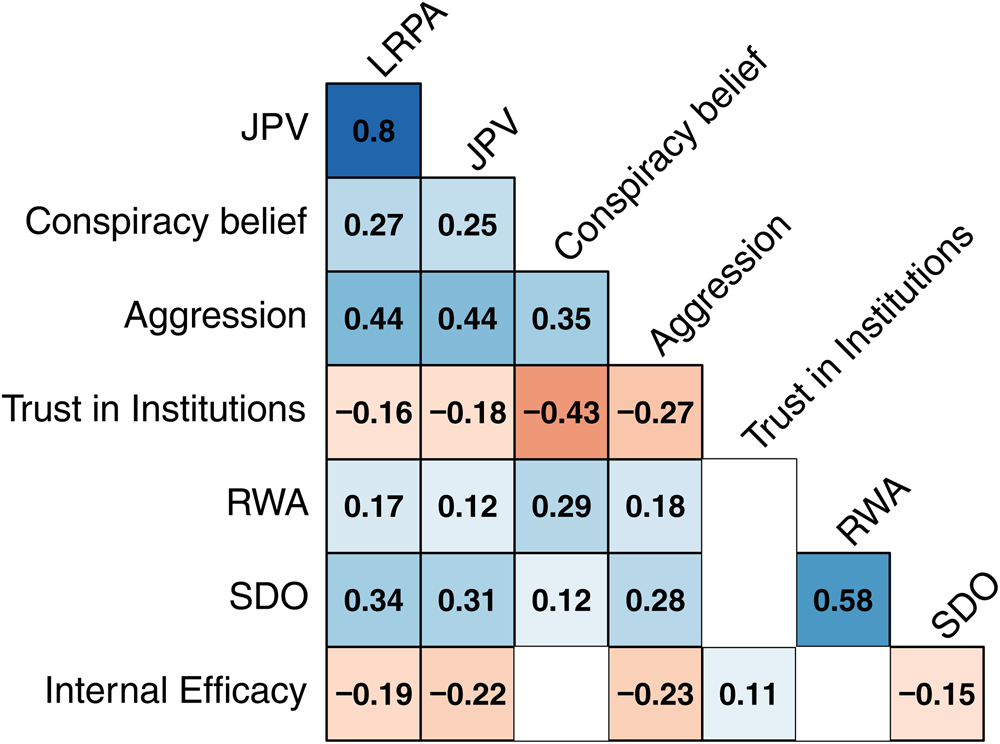

Figure 2 shows the Pearson's correlation between the extracted latent scores in the data. The figure shows some interesting patterns of associations between the variables. The first point worth noting is that the two indicators of endorsement of political violence are very highly correlated. This provides some convergent validation to our LRPA battery. The two indicators are also positively correlated with aggression and with the SDO scale. The first finding is not surprising, as it makes intuitive sense that people who are more likely to support political violence are also more aggressive. The positive association with SDO is somewhat more surprising, as social dominance orientation should be associated with a preference for violence only when it implies maintaining the social hierarchies (see Henry et al., Reference Henry, Sidanius, Levin and Pratto2005), whereas our indicators of endorsement of political violence describe situations in which violence is used as a form of protest or generally a disruptive behavior. Finally, the two indicators correlate negatively with both trust in institutions and internal efficacy.

Figure 2. Correlation plot of latent factors. Blank cells indicate non-significant correlations.

Looking at conspiracy belief, the variable is positively and significantly correlated with both indicators of endorsement of political violence, even though the associations are not very strong (0.27 with the LRPA index and 0.25 with the JPV index). In comparison, the variable correlates more with aggression (0.35), trust in institutions (−0.43, meaning that higher trust in institutions corresponds to lower tendency to believe in conspiracies and vice versa), and the RWA scale (0.29). The correlation with SDO is weak, and the one with internal efficacy is not even significant, indicating that the latter variable is a poor proxy for a low sense of control, which has been repeatedly shown in past research to correlate with conspiracy belief.

All in all, the correlation analysis shows a positive association between the tendency to believe in conspiracy theories and to endorse violent or radical political actions, even though the observed correlations are not very strong. Yet, this provides some basic support for our expectation, namely that conspiracy theories might act as an intervening factor in the individual pathway to radicalization. Granted that our observational design does not allow us to tell whether conspiracy belief causes radicalization, nor does it provide any information regarding the dynamics of the process, the presence of a positive and significant association between belief in conspiracies and support for political violence is the first necessary step in supporting our model. The next step will be to assess the robustness of this association when controlling for other individual characteristics in a multivariate regression.

Regression analysis

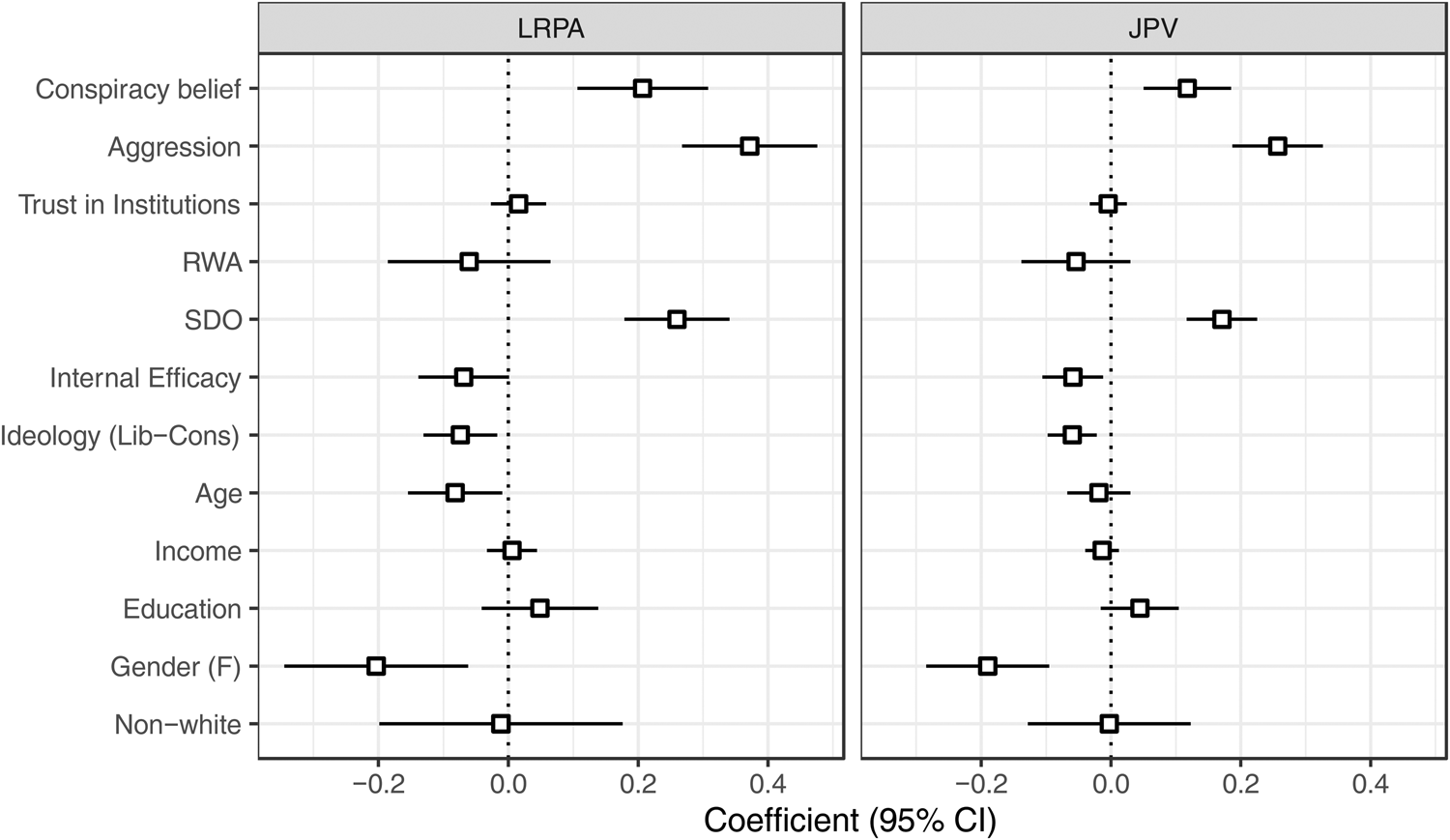

To determine whether the association between belief in conspiracies and endorsement of political violence is robust to the inclusion of control variables, we run two linear regressions with LRPA and JPV as dependent variables. We include in our models all the latent predictors as well as the manifest socio-demographic and political characteristics discussed above. The results are shown in the coefficient plots in Figure 3.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Coefficient plots for linear regression models of LRPA and JPV.

As the figure shows, the regression models confirm the positive and significant association between belief in conspiracy theories and endorsement of political violence. Because the dependent variables and all the continuous predictors are standardized (with the exception of liberal-conservative ideology, that we kept on the original 7-point scale centered around the middle), the coefficients are comparable to the correlation coefficients discussed above. Here we can clearly see that, when controlling for other predictors, the effect of conspiracy belief drops, however it does to a greater degree in the model for JPV than in the one for LRPA. In fact, the coefficient of conspiracy belief in the LRPA model is almost double as large as the one in the JPV model (0.21 vs. 0.12). This difference can be observed also with other variables, such as aggression and SDO, which are both more strongly associated with LRPA than with JPV. Otherwise, the two models are remarkably similar, including the fit: in both cases, the adjusted R 2 is 0.29.

Looking at the coefficients of the other latent variables, this analysis confirms the pattern observed in Figure 2, with the exception of trust in institutions and RWA, which are now non-significant. What remains to be discussed are the coefficients of the other control variables. One indicator which has a robust and negative effect is gender: females are consistently less likely than males to endorse violent political actions. Age is also negative and significant in the LRPA model, indicating that older subjects are less likely to legitimize radical political behaviors. Finally, and interestingly, ideology has a negative and significant coefficient in both models. As the variable ranges from ‘extremely liberal’ to ‘extremely conservative’, a negative coefficient implies that more conservative respondents in our sample are less likely to endorse political violence than the more liberal ones. This is not likely to be due to the ‘challenger’ status of respondents identifying as liberals, as at the time the data were collected, the White House was still controlled by the Democrat president Barack Obama. Our data do not allow us to investigate the nature of this relationship any further; however, we find it particularly interesting and potentially worthy of further investigation in the future.

All in all, the regression models confirm our expectation: belief in conspiracies is associated with the endorsement of violent political behaviors, even after controlling for some factors that are likely to occur earlier in the individual pathway toward radicalization (such as aggression). While these analyses do not tell anything regarding the direction of the causal path between the two indicators, theoretical models of radicalization place narrative and community, two factors that are usually found in religion and/or ideology, in a position prior to radicalization in a hypothetical causal path. It will be the task of future research to investigate the dynamics of this process more carefully, to identify the potential role of conspiracy theories for individuals' acceptance of violence as a means to reach political goals.

Concluding remarks

In the last decade, violent political events, often but not always triggered in the context of protests, have been rising in Western democracies. At the same time, there has been a steady increase in the diffusion of conspiracy theories in political communication, a phenomenon that has captured the interest of scholars for its growing political relevance. In this article, we investigate the association between the two phenomena, focusing on citizens' attitudes toward political violence. Drawing from psychological literature conceptualizing the process of radicalization as a pathway from individual predispositions to radicalism, we theorize that conspiracy theories act as an intervening factor channeling people's frustration toward political goals. We provide some descriptive evidence in support of our expectations by looking at the association between individual belief in conspiracies and endorsement of political violence using MTurk data collected in the US in 2014.

Pathway models of radicalization are not the only way to explain politically violent behavior, but they have two features that are important for our purpose. First, at the starting of the path that they describe, there are typically non-violent individuals who experience some sort of personal crisis, what Kruglanski et al. call a loss of ‘personal significance’ (see Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014, Reference Kruglanski, Jasko, Webber, Chernikova and Molinario2018). In this view, all people share a fundamental need for consideration, which contributes to their self-esteem as well as to their feeling to be in power and control of the events that determine their own life. However, people often experience failure, humiliation, or other traumatic circumstances, which might target them as individuals or as part of a group. These negative experiences may trigger feelings of powerlessness and resentment, and prompt a need to react, to do something to re-establish a sense of self-worth. This leads to the second reason why pathway models of radicalization are useful for our purpose: the importance that they place on a narrative that identifies the nature of the problem and possibly a resolution, or at least a scapegoat. In many theoretical accounts of radicalization, individuals in crisis are drawn toward a narrative. Given that this literature is mainly interested in terrorism, the narrative that is typically considered is religion. However, conspiracy theories share the same characteristics that make religions good narratives. It has been shown that belief in conspiracies is not necessarily based on a logical evaluation of their content, but rather on their fit with a wider, more abstract worldview according to which some powerful individuals are in control of the major (and usually negative) events occurring in the world. In other words, conspiracy theories offer an interpretation of reality, and they identify a cause for people's distress, usually an enemy. Moreover, very much like religion, conspiracy theories set the borders of a community of believers. Hence, conspiracy theories can be so attractive and all-encompassing that individuals who believe in them might start losing sight of their life goals that are not the ‘focal goal’ identified by them (see Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Gelfand, Bélanger, Sheveland, Hetiarachchi and Gunaratna2014).

How does this relate to attitudes toward political violence? First of all, conspiracy theories are political in nature. Most of them seek to explain politically-relevant events, and they point to an enemy that is typically institutional. In these terms, the process of radicalization that we have described here is rather different from the one of religious terrorists. In our case, we focused on non-conventional and hostile political behaviors because they are arguably the ‘easiest’ form of political violence. Moreover, we looked at attitudes, as they represent a middle step before eventual behaviors. Our outcome is measured using a battery of justification of political violence (JPV – Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Huq, Bradford and Tyler2013) as well as a brand-new scale of legitimization of radical political action (LRPA) developed by us. Our findings support our theoretical expectations. Belief in conspiracies, measured using the ‘generic’ scale by Brotherton et al. (Reference Brotherton, French and Pickering2013) is associated with both our indicators of endorsement of political violence. This association holds even controlling for factors that are expected to intervene at different stages of the radicalization process. One such factor is aggression, which has been argued to explain why people tend to believe in conspiracy theories.

By positing this association, we are not arguing that people who believe in conspiracy theories are potential terrorists, nor that they all support violent political acts, very much in the same way as nobody would argue that fervent religious people are potential suicide bombers or supporters of terrorist organizations. Our goal is rather to systematize an association for which anecdotical evidence is mounting – see the presence of QAnon believes in the storming of the Capitol Hill in January 2021. However, the present analysis is just a first step on this path, and as such it has several weaknesses. First, our correlational analyses say nothing about the causal direction between belief in conspiracies and endorsement of political violence. Second, despite controlling for several socio-demographic and political factors, our analyses are conducted on a convenience sample that is not adequately representative of the overall US population. A potential direction for future research would therefore be to show precisely how the individual pathways toward radicalization are structured. Do factors such as powerlessness and resentment really cause people to look at conspiracy theories to make sense of reality? And what about the effect of such conspiracies on the final attitudes? These are difficult questions to answer, given the nature of the topic, as well as the long timeframe in which radicalization processes develop. However, as recent history suggests, these questions are becoming increasingly important.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.17

Funding

The data used in this article have been funded by the Research Support Scheme (RSS) of the Central European University.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erin Jenne for helping develop the ‘Legitimate Radical Political Action’ (LRPA) scale used here. We also thank the present and past members of the Political Behavior Research Group (PolBeRG) at the Central European University, some of whom provided helpful feedbacks on earlier versions of this paper. In particular, we thank Krisztián Pósch, who pointed us to the ‘Justification of Political Violence’ (JPV) scale used in the analyses, and Paul Weith, who participated in early iterations of this project.