Introduction

The advent of interactive social networking site (SNS) has reopened the debate on whether the web can become an uncoerced public sphere (e.g. Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2005) that enhances accountability and responsiveness. Indeed, due to their potential interactivity, SNS like Facebook (FB) and Twitter could favor participatory and transparent democracy (Waters and Williams, Reference Waters and Williams2011; Avery and Graham, Reference Avery and Graham2013), allowing citizens to play a role in the development of the democratic polity (Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2005).

So far, the literature has investigated whether the interactions that take place on SNS influence the attitudes and behavior of individual citizens (Kushin and Yamamoto, Reference Kushin and Yamamoto2010; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Johnson, Seltzer and Bichard2010; Effing et al., Reference Effing, van Hillegersberg and Huibers2011; Bond et al., Reference Bond, Fariss, Jones, Kramer, Marlow, Settle and Fowler2012). After the Arab Spring the role of SNS in undermining authoritarian regimes has also been widely studied (Shirky, Reference Shirky2011; Howard and Parks, Reference Howard and Parks2012). Conversely, in democratic regimes, scholars have mainly paid attention to how online activism can influence public policy (for a review: Dekker and Bekkers, Reference Dekker and Bekkers2015), while the effect of SNS on ‘politics’ (specifically, legislative politics) has been less investigated.

Starting from the literature on ‘competing principals’ (e.g. Carey, Reference Carey2007; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015), the present paper attempts to fill this gap. The literature on legislative politics highlights that the party leadership is the first principal able to affect the behavior of Members of Parliament (MPs). However, depending on the institutional context, legislators can be influenced by other rival principals such as their constituency or factional leaders. In light of this, the interaction between politicians and SNS users that occurs on Web 2.0 platforms can expose MPs to pressure from such virtual public sphere, which can act as another ‘competing principal’ consisting of the audience of the politicians’ Facebook ‘friends’ (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015).

SNS conversations allow users to directly express their opinions to the MP, who becomes aware of the ideas of his/her Facebook friends. In turn, this online interaction may enhance the responsiveness of MPs to activated public opinion.

To assess whether parliamentary behavior can be affected by the power of Facebook, we focus on the selection of the Italian Head of State that took place in mid-April 2013. This election dramatically revealed the potential of SNS to exert pressure on MPs and led to a heated debate over whether the power of Facebook contributed to the failure of the candidacy of Franco Marini as Head of State.

Many influential journalists, politicians, and political analysts such as Luca Sofri, Giuliano Ferrara, or Bruno Vespa argued that the pressure exerted through SNS by the PD rank-and-file on their elected officials led to the defeat of Marini (for a review of these comments: Chiusi, Reference Chiusi2013; Pennisi, Reference Pennisi2013). For instance, Di Traglia and Geloni (Reference Di Traglia and Geloni2013) claimed that the PD fell under the fire of tweets and unprecedented spamming (with ~110,000 serial messages sent to the e-mail addresses of PD deputies). Roberto Cota, member of the Northern League, complained about the fact that the Head of State was being elected through Twitter. Prominent PD politicians agreed with this assessment: the former party leader Dario Franceschini observed that for the first time, the party had experienced the power of Facebook and Twitter as a source of influence in the political debate, and the behavior of the parliamentary party group selected through party primaries was affected by pressure from the voters exerted through SNS. Other PD politicians retained the same view arguing that, through Facebook and Twitter, MPs are in contact with the rank-and-file and therefore they are less autonomous than they used to be (Chiusi, Reference Chiusi2013). Stefano Fassina, who eventually became junior minister, expressed an even more negative judgment, as he claimed that, to preserve their credibility, the political class should not surrender to ultimatums coming from a dozen of tweets or a hundred ‘likes’ on Facebook, and he criticized those MPs that followed the messages of their Facebook friends because doing so meant that they were no longer part of the ‘ruling class’ and had simply become ‘followers’ of such vocal minority (Di Traglia and Geloni, Reference Di Traglia and Geloni2013).

Not all the political analysts, however, shared the same view. Others emphasized that MPs, in fact, did not surrender to the pressure coming from the Web (Chiusi, Reference Chiusi2013; Sentimeter, Reference Sentimeter2013; Zampa, Reference Zampa2013) as MPs did not took into consideration other candidates, such as Emma Bonino or Stefano Rodotà, whose approval on Facebook and Twitter was rather strong (Chiusi, Reference Chiusi2013; Sentimeter, Reference Sentimeter2013). As a consequence, their choice to boycott the candidacy of Franco Marini could have been driven by other factors.

The present paper sheds light on this puzzle. While the Head of State is elected by secret ballot, we will focus on the expression of public dissent to investigate the determinants of party unity. Using a novel and original data set constructed by gathering the data available on SNS, we analyze 12,455 comments published on the Facebook walls of 423 Italian MPs. Based on these comments, we assess the degree of pressure placed on MPs belonging to the Democratic Party by internet users who opposed Marini, measured as the number of Facebook messages posted to criticize this choice.

In so doing, we will evaluate whether this pressure affected an MP’s likelihood to express public dissent against the candidacy of Marini, while controlling for a number of potentially confounding factors and alternative explanations provided by the literature on legislative behavior (Carey, Reference Carey2007; Kam, Reference Kam2009; Tavits, Reference Tavits2009; Curini et al., Reference Curini and Zucchini2011; Eggers and Spirling, Reference Eggers and Spirling2014; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015) and intra-party dissent (Bernauer and Braüninger, Reference Bernauer and Braüninger2009; Giannetti and Laver, Reference Giannetti and Laver2009; Spirling and Quinn, Reference Spirling and Quinn2010; Haber, Reference Haber2015; Ceron, Reference Ceron2015a).

The results of our statistical analysis reveal that SNS pressure did not increase an MP’s likelihood of expressing public dissent, which was instead affected by elements that traditionally affect party cohesion in parliamentary votes, such as experience, the selection of legislators through primary elections, and affiliation with a minority faction.

Notably, due to the substantial pressure exerted through SNS in 2013, this context represents the most likely case for finding evidence of an effect of SNS. In turn, it represents a stringent test for hypotheses concerning the lack of internet effects. Even in a favorable environment, we did not find any SNS effect. Accordingly, we can reasonably expect to observe the lack of any SNS effect even under less favorable conditions.

The paper is organized as follows. First section summarizes the literature on social media and politics. Second section discusses the role of SNS as a competing principal and offers corresponding hypotheses. Third section introduces the political context in April 2013, when the Parliament had to select the President. Fourth section describes the measurement of the dependent and independent variables. Fifth section reports the results of the analysis. Sixth section concludes.

Social media and politics in Italy (and beyond)

The role of social media in politics is a highly debated topic in Italy (e.g. Bentivegna, Reference Bentivegna2014) as this country represents – for several reasons – a critical case. As a matter of fact, Italy ranks at the top levels for trust in the internet.Footnote 1 Furthermore, both the current Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi (leader of the Democratic Party), and the main opposition party (Five Stars Movement) have built their fortunes on the use of the internet and emphasize the role of the web as a source to promote political participation. As a consequence, several scholars have analyzed SNS to study Italian electoral campaigns (Vaccari et al., Reference Vaccari and Valeriani2013; Ceron and d’Adda, Reference Ceron, Curini and Iacus2015; Ianelli and Giglietto, Reference Ianelli and Giglietto2015) or Italian leaders (Ceron et al., Reference Ceron and Negri2014; Vaccari and Valeriani, Reference Vaccari, Valeriani, Barberá, Bonneau, Jost, Nagler and Tucker2015). Focusing on Italy, many other studies investigated the link between SNS and public policy (Ceron and Negri, Reference Ceron, Curini, Iacus and Porro2016), political trust (Monti et al., Reference Monti, Rozza, Zappella, Zignani, Arvidsson and Colleoni2013; Ceron, Reference Ceron2015b), or political news (Giglietto and Selva, Reference Giglietto and Selva2014; Ceron et al., Reference Ceron and d’Adda2016).

In Italy and outside Italy, the literature on social media and politics has mainly investigated the topics described above, focusing on electoral campaigns and electoral forecasts or analyzing the effect of online activism on public policy, though citizen-initiated online participation has been understudied (Dekker and Bekkers, Reference Dekker and Bekkers2015: 9; Ceron and Negri, Reference Ceron, Curini, Iacus and Porro2016). Apart from agenda-setting studies (e.g. Bekkers et al., Reference Bekkers, Beunders, Edwards and Moody2011), little attention has been devoted to the effect of SNS on ‘politics’, rather than ‘policy’ and to the interaction between politicians and citizens.

In recent years, however, the growth in the use of social media has created a wide online audience and has made the web attractive to parties and candidates. As a consequence, a growing number of politicians are now active on SNS to communicate with citizens or reach new voters;Footnote 2 such online interaction can dramatically alter citizens-elite communication (Parmelee and Bichard, Reference Parmelee and Bichard2012; Gainous and Wagner, Reference Gainous and Wagner2014; Ecker, Reference Ecker2015) and deserves further investigation.

It has been argued that this relationship could be asymmetrical and unidirectional if politicians are primarily interested in spreading their message and rely on a top-down style of communication, looking at citizens more as ‘followers’ than as ‘friends’ (Sæbo, Reference Sæbo2011; Larsson, Reference Larsson2013).

The interactive nature of SNS, however, makes it difficult to ignore another person’s opinions. Given that SNS allow voters to dialogue online with their representatives (Mackay, Reference Mackay2010), politicians are ultimately exposed to citizens’ viewpoints and to the changing climate of opinion broadcast by other SNS users (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Broersma, Hazelhoff and van ‘t Haar2016). Indeed, recent studies attest a growth in the online interaction between politicians and citizens (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Jackson and Broersma2013; Larsson and Ihlen, Reference Larsson and Ihlen2015), which is perceived by citizens as real interpersonal contact and conversation (Lee and Jang, Reference Lee and Jang2011).

Competing principals in the age of SNS: literature and hypotheses

We know that the online behavior is publicly observable, therefore politicians may be affected by the need to display loyalty to preserve party unity and avoid being punished by the party leadership. As such, they could decide to act in accordance with the party line and broadcast content that is coherent with it.

However, SNS provide them with the extraordinary opportunity to communicate directly with voters. On the one hand, politicians can spread messages tailored to their supporters with a content that differs from the official party line, particularly in contexts where intra-party competition provides incentives to do so (Skovsgaard and Van Dalen, Reference Skovsgaard and Van Dalen2013; Vergeer et al., Reference Vergeer, Hermans and Sams2013; Adi et al., Reference Adi, Erickson and Lilleker2014). On the other hand, as long as politicians are exposed to the opinions expressed on SNS (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Broersma, Hazelhoff and van ‘t Haar2016), they can feel a pressure to conform to such opinions in order to make citizens and voters happy. Indeed, when politicians engage with voters their evaluations can improve and politicians can get some electoral benefits (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Moon and Grant2010; Vergeer and Hermans, Reference Vergeer and Hermans2013).

The importance of interacting on SNS is even more crucial in light of the recent change in the organization of political parties. To explain such change, Scarrow (Reference Scarrow2015) introduced the concept of ‘Multi‐Speed membership’ highlighting that nowadays parties are composed of multiple categories of affiliates. In order to respond to the membership decline, parties blurred the boundaries between members and ‘self‐identified supporters’ (those who want some kind of party contact but are not interested in formal membership) allowing such networks of ‘friends’ and ‘followers’ to participate in intra-party decision-making (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015). The interactive Web 2.0 plays a key role in this process. Indeed, ‘friends’ and ‘followers’ use SNS to freely join a party‐led communication network and to interact with politicians. On the one hand, citizens receive party messages via Twitter or Facebook (Vaccari and Valeriani, Reference Vaccari, Valeriani, Barberá, Bonneau, Jost, Nagler and Tucker2015). On the other, they have the opportunity to speak back by commenting on texts posted by politicians or by sending them direct messages (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015). In light of this, SNS can be viewed as a new ‘competing principal’ with which politician have to deal.

Research Question 1 Does the interaction with the opinions of ‘friends’ and ‘followers’ affect the behavior of politicians?

The literature on legislative behavior points to the relevance of the party leadership, which sets the party line and is the first and foremost principal responsible for ensuring that the parliamentary behavior of MPs will conform to that line. When the individual career of each MP primarily depends on the support of the leadership, or when an MP requires the leader’s aid to realize a goal (e.g. be re-elected, pass a law, or be appointed to office), we can expect to observe a higher degree of loyalty toward the party line. The same outcome is observed when MPs closely share the leadership’s ideological position or when the leader is stronger and able to impose discipline (e.g. through sanctions) even on reluctant MPs.

Beside the party leadership, however, the literature underlined the existence of many other ‘competing principals’ (e.g. Carey, Reference Carey2007; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015). Scholars highlighted that important sources of loyalty and dissent are linked with the electoral system (e.g. Carey, Reference Carey2007; Tavits, Reference Tavits2009; Curini et al., Reference Curini and Zucchini2011; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015), the intra-party structure (Bernauer and Braüninger, Reference Bernauer and Braüninger2009; Giannetti and Laver, Reference Giannetti and Laver2009; Spirling and Quinn, Reference Spirling and Quinn2010; Haber, Reference Haber2015; Ceron, Reference Ceron2015a) or personal characteristics of the MP such as expertise (Eggers and Spirling, Reference Eggers and Spirling2014). Depending on the institutional and electoral contexts and on the organizational structure of the party, MPs can directly rely on the consent of voters to be re-elected and improve their status. Alternatively, in internally divided parties, MPs may rely on the support of their factional leader, who trades rewards for loyalty. Thus, in addition to the party leadership, MPs can also be exposed to the demands of their constituency or intra-party faction, which may conflict with the party line.

After the change in party organization discussed above, the advent of interactive SNS can extend the concept of ‘competing principals’ further. Online public opinion can represent an additional competing principal beyond the party leadership and the MP’s faction or constituency. The users of SNS can provide the MP with resources such as their network of contacts, which can enhance the MP’s visibility at little or no cost (Gueorguieva, Reference Gueorguieva2008; Vergeer et al., Reference Vergeer, Hermans and Sams2013), and their own support, which can translate into online popularity provided that several users support the MP in online conversations.

In turn, online popularity can imply media popularity whenever the MP becomes sufficiently famous online that mass media begin to provide him/her with coverage in more traditional channels such as television or newspapers. For the same reasons, an MP should be concerned by negative online popularity and should have an incentive to avoid instances in which the users of SNS give him/her negative exposure.

Finally, the SNS audience can also become a potential source of information for micro-targeting, fundraising, and online campaigning (Gueorguieva, Reference Gueorguieva2008; Vergeer et al., Reference Vergeer, Hermans and Sams2013). In summary, for all of the abovementioned reasons, an MP could be interested in cultivating a positive relationship with his/her SNS audience (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Moon and Grant2010; Vergeer and Hermans, Reference Vergeer and Hermans2013) and consider their demands, particularly those that are more salient for the audience. Accordingly, MPs will become increasingly responsive as the pressure placed on them by their Facebook friends grows.

Hypothesis 1 MPs exposed to higher levels of pressure from their Facebook friends are more likely to express dissent from the party line.

Moreover, the SNS environment can become a useful tool that allows the MP to interact with a more traditional ‘principal’, that is, his/her constituency of voters and rank-and-file members. Because MPs have an interest in being re-elected, they will behave according to the desires of those who can grant them the re-election. When the candidate selection process primarily depends on the support of their constituencies, MPs have an incentive to consider their requests and, in this context, SNS are useful for revealing the true preferences of voters and allowing the rank-and-file to have their voices heard. Provided that the MP can cultivate a direct relationship with his/her constituents through SNS, the incentive to cultivate personal loyalties to him/her among voters by heeding his/her constituents’ desires should increase the likelihood of expressing dissent from the party line, whenever this line diverges from the constituency’s stance. For instance, when MPs are selected through party primaries, they will become increasingly responsive to requests from SNS as the pressure placed on them by their Facebook friends grows, compared with cases in which the party leader has the final say on the party list.

Hypothesis 2 MPs exposed to higher levels of pressure from their Facebook friends are more likely to express dissent from the party line when they were selected through party primaries.

The selection of the Italian Head of State in 2013 and the failure of Franco Marini: all because of Facebook?

In April 2013, the renewed Italian parliament had to select a successor to Giorgio Napolitano as Head of State. In accordance with the Constitution, the election of the Head of State is the responsibility of a number of delegates, consisting of MPs (members of the Chamber of Deputies and senators) and representatives selected by the 20 Italian regions, who elect him/her by secret ballot.Footnote 3 Through the third ballot, a qualified two-thirds majority is required; thereafter the Head of State can be selected by an absolute majority. In 2013, there were 1007 delegates, including 630 deputies, 315 senators, four senators for life, and 58 regional representatives (three per region except for the small Valle D’Aosta, which only sends one). The threshold required to elect the President in one of the first three ballots was 672 and fell to 504 beginning with the fourth ballot.

While reaching a qualified majority is already a difficult task, the astonishing results of the 2013 Italian general election, in which no coalition won a majority of seats, further complicated the bargaining process. The center-left coalition only retained 493 delegates, a number insufficient to elect the new President, and hence it was crucial to compromise with rival parties. In an attempt to reach an agreement with the center-right coalition, the Democratic Party suggested the election of Franco Marini.

Marini started his political career in the Christian Democracy (DC) and, after the dissolution of the DC, he became the leader of the Italian Popular Party, the center-left heir of the DC. Marini has always retained policy positions in line with the catholic democratic tradition and, within the PD, he was considered one of the most moderate and influent politicians. As a moderate, he was deemed suitable to get elected by a wide majority after reaching a compromise with other parties.

Although intended to establish an inter-party agreement with potential partners to surpass the threshold of votes required to elect the President, this choice was problematic and disputed at the intra-party level. The nomination of Marini, in fact, was also seen as an attempt to build a bridge between the center-left PD and the center-right People of Freedom (PDL), in order to form a Grosse Coalition including these two parties. Such Grosse Coalition would have overcome the political instability generated after the elections allowing the PD leadership to gain the premiership.

Driven by personal career ambitions or by the will to halt the negotiation with the PDL, several senior politicians and rank-and-file members of the highly factionalized Democratic Party criticized the candidacy of Marini, and some factional leaders refused to endorse him. Matteo Renzi, head of the minority faction Renziani and destined to eventually become the party leader, was one such individual, and he argued that the election of Marini would have been damaging for the country.

To resolve this dispute, on 17 April, the day before the first ballot, the party organized a meeting with all center-left delegates entitled to select the Head of State. The PD leader, Pierluigi Bersani, officially nominated Marini and demanded the support of the delegates, many of whom immediately refused to do so. In the heated debate that followed, several delegates declared their refusal to toe the party line, while others (including those belonging to the left-wing ally of the PD) left the room before a final decision was made. Simultaneously, several PD members, activists, and sympathizers were protesting outside the building in which the meeting was held, and many others had already been mobilizing online through SNS over the preceding days to demonstrate their opposition to the Marini candidacy and to any other cooperation with the center-right. During the meeting, many delegates received numerous e-mails, SMS messages, or messages posted on Facebook and Twitter sent by rank-and-file members unwilling to accept Marini as the new President. This was only the tip of an iceberg of dissent, expressed both online (on SNS) and offline (by young PD members who occupied many local headquarters of the party), which had affected the party for a few days, that is, beginning when Marini was first mentioned as a candidate and the idea of a ‘Grosse coalition’ between the center-left and the center-right was at stake.

Ultimately, among the 423 delegates belonging to the PD, only 342 casted a vote during the meeting, but the assembly finally approved the proposal by majority decision, with 222 PD delegates voting in favor, 90 opposed and 30 abstentions.

However, in the first parliamentary ballot held on the subsequent day (18 April), Marini failed to pass the threshold and obtained only 521 votes, well below the potential total of delegates (716) belonging to the three groups that supported his/her candidacy, that is, the PD, the center-right coalition (People of Freedom and minor allies), and the centrist electoral cartel Civic Choice. The secret ballot highlighted tremendous dissent over the nomination of Marini, who received 195 fewer votes than expected, and the PD withdrew his/her candidacy. On the fourth ballot, another PD candidate, Romano Prodi, witnessed the same fate, and the party, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, ultimately decided to support the re-election of Napolitano, who was confirmed President on 22 April, on the sixth ballot, by a substantial majority (738 votes).

The failure of Marini, dismissed by no fewer than 195 rebels, and the subsequent failure of Prodi, buried by 101 dissenters, generated heated debate in the media, which began to speculate on the role of SNS in promoting intra-party division.

SNS pressure and dissent on Marini’s candidacy

Dependent variable

Studies on party unity usually relies on roll call votes as a direct and observable indicator of cohesion. Recently, scholars have also analyzed the propensity for dissent in parliamentary votes of individual MPs (Tavits, Reference Tavits2009; Curini et al., Reference Curini and Zucchini2011; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015). Here we will focus on dissent as the dependent variable and we will scrutinize the determinants of the expression of public dissent on the candidacy of Marini. To do so, we construct a new data set that contains information on the 423 Democratic Party delegates responsible for selecting the new Head of State. PD delegates account for 293 members of the Chamber of Deputies, 105 senators, and 25 regional delegates. By analyzing this case study, we will be able to assess the impact of SNS by contrasting the behaviors of PD delegates while holding country-specific and party-specific factors constant. Furthermore, we exploit two peculiarities of the PD that allow us to test our hypotheses: we can distinguish MPs selected by the leadership from those selected through primary elections, and we can account for the role of intra-party minority factions, which exist within many parties but are clearly identifiable and observable within the PD.

The election of the Head of State is held through secret balloting, a feature typical of Italian politics, at least until 1988, when it was eliminated except in certain votes such as this one. Secret voting played a crucial role in several key parliamentary votes during the First Italian Republic (1948–93), and party factions have typically exploited the secret ballot as a shield to halt unwanted bills and to defeat governments, thereby fostering a cabinet reshuffle to alter the distribution of ministers among factions (Giannetti, Reference Giannetti2010). Secret voting, by definition, does not allow us to track the actual behavior of MPs. As a consequence, we analyze party dissent by focusing on public declarations of MPs, which sometimes can provide more direct insights into legislative decision-making (for a similar view: Ecker, Reference Ecker2015; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2015). Therefore, we measure the propensity to manifest public dissent against the candidacy of Marini before the end of the first ballot (18 April).

This includes MPs who did not vote in favor of Marini during the PD assembly held on 17 April (i.e. voted against, abstained, or left the room in protest of his selection)Footnote 4 and those who expressed, through traditional media (e.g. press releases and interviews) or through social media (Facebook, Twitter), their intention to not vote for Marini in the ballot (either by voting for someone else, remaining home, or casting a blank vote).Footnote 5

This task has been facilitated by the fact that several politicians also declared their preferences through SNS during the days before the first ballot. For instance, some delegates said, ‘I will vote Rodotà’, and others expressed dissent by remarking, ‘I say in a clear and transparent manner that I will not vote for Marini’. Conversely, others said ‘I will toe the line, as I usually do in relevant parliamentary votes like this’.

In summary, the dependent variable, Dissent, is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when the MP expressed public dissent and declared his/her unwillingness to support Marini. Although the true vote cast by each politician is unknown (being secret), this variable represents a good proxy for it: in our data set, we detect 158 PD delegates that clearly expressed their intention to defect. The total number of defections on the secret ballot was 195, but some of these defections likely came from centrist and center-right parties, as several center-right politicians had also declared their intention to defect from the agreement. Accordingly, we have been able to provide a nearly comprehensive picture of the PD dissenters.

Notwithstanding any potential link between (visible) public declarations and (unobservable) secret behavior, the variable Dissent is even more interesting per se. If compared with the secret ballot, the decision to publicly manifest dissent is both more costly, in terms of punishment and potential sanctions enacted by the party leadership, and more rewarding, in terms of approval granted by the competing principals such as the factional leader, the real constituency of voters, or the virtual constituency of the users of SNS and Facebook friends. As such, only MPs that explicitly manifest dissent will pay the cost associated with this public declaration, but only they can reap the major benefits of their defection (e.g. the gratitude of factional leaders and the support of dissenting voters and the users of SNS). In this regard, to double check the robustness of our findings, we will also consider an additional dependent variable, Explicit Dissent, which represents a subset of the previous one. Explicit Dissent is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 when the MP expressed a publicly visible dissent and declared his/her unwillingness to support Marini on traditional media or on social media (and not only in the PD Assembly, which was a rather private meeting). Overall, 147 MPs expressed Explicit Dissent. By considering this additional variable we can more directly test our theoretical framework as MPs could gain recognition by their constituents and could claim credit for the dissenting behavior only if they publicly communicate it on the media.

Independent variable

The main independent variable, used to test Hypotheses 1 and 2, is related to the pressure placed on MPs through SNS and the extent of such pressure. To measure SNS pressure, we focused on Facebook for a number of reasons. First, the comments published by Facebook users and the Facebook friends of politicians are usually publicly available (for those politicians who make their profiles public) or can be easily accessed by sending a friend request to the politician, whereas we do not have access to private e-mails or SMS messages. Moreover, on Facebook we need, at most, to become the friend of a politician to view the public messages sent to him/her, whereas on Twitter observing direct messages such as ‘@matteorenzi you should not vote for Marini’ is complicated because we would have to be a follower of both the sender and receiver of the message. The tweets sent to politicians do not appear on his/her Twitter page.

It could be argued that the official profile of politicians are managed by their staff and politicians may not have been informed of such pressure. For this reason, whenever available, we focused on the private Facebook profile of each politician, which is usually managed by himself and not by his/her staff. In very few cases, the private profile was not available and we reverted to his/her public page. Even so, the online pressure and off-line demonstrations generated a heated debate, not only on social media but also in the media and in the political agenda. Therefore, it is very likely that each staff has at least informed the politician on the mood of his/her Facebook friends, summarizing the degree of pressure put on the Facebook profile.

The variable FB Pressure has been measured as follows. For each politician, we counted the total number of comments posted on his/her Facebook wall that contain an incitement to not vote for Marini or suggested to vote for another candidate (e.g. Emma Bonino, Romano Prodi, Stefano Rodotà).Footnote 6 For instance, several comments that have been coded as ‘pressure’ criticized the choice of Marini by merely saying ‘Marini no!’ or ‘Beware that voters want change, while voting for Marini is not a change’ and ‘Please, promise not to support this candidate jointly with the center-right’. Other comments asked MPs to support another candidate: ‘Listen to voters: choose Rodotà’ or ‘By voting Prodi we can get rid of Berlusconi. Alternatively if voting Prodi is unfeasible vote Rodotà’.Footnote 7 Conversely, we did not find comments supporting Marini.

We considered all comments written between 12 April (1 week before the first ballot) and the day on which the MP’s choice was observed. This date corresponds to 17 April (at midnight) when the PD assembly ended and the MPs were forced to make a choice, while we also considered the comments published thereafter for those MPs that were uncertain and openly expressed their position only on 18 April.Footnote 8 A total of 5861 comments were written by Facebook users either to criticize Marini (3810) or in support of someone else (2051).

FB Pressure takes the value of zero when the delegate does not have a Facebook profile. This operationalization appears reasonable, as the MPs who are not active on Facebook, by definition, are not exposed to pressure coming from that social networks. Furthermore, the absence of a Facebook profile may also signal that the MP has a rather limited familiarity with internet and new technologies; hence he is likely detached from SNS pressure and less subject to the impact of the internet.

Control variables

In addition to SNS pressure, we also account for the role played by more traditional competing principals. The Italian electoral system at the time was based on closed-list PR; however, 2 months before the election, the PD organized a party primary to select its candidates. While a majority of PD MPs was selected through primary election, not all of them ran in the primary. The party leadership decided to select 100 candidates who were appointed through a type of reserved party list. Analogously, the 25 PD regional delegates were indirectly selected by the members of the regional councils rather than by the rank-and-file and should therefore be more responsive to the party line. To account for this, we create the variable Party Primary, which allows us to distinguishing between MPs that ran in the primary election (value one) and those who were appointed via the reserved party list or selected by the regional party leadership (value zero), who should be more loyal.

We control for the role of factional affiliation focusing on the Renziani faction, which was the main minority faction at that time. The factional leader, Renzi, opposed the candidacy of Marini and this is a further rationale for such choice. The variable Minority Faction, therefore, takes the value of 1 when the MP belongs to this faction and the value of zero otherwise.Footnote 9 We assessed factional membership based on the expert judgments of two of that faction’s leaders. According to their judgment, the share of Renziani delegates (12.3%) closely approximates the number of Renziani MPs (13%) as estimated by other external sources (Catone, Reference Catone2013).

The variable Seniority, which records the number of years that each politician had spent in parliament, controls for the impact of experience, which should enhance loyalty (e.g. Eggers and Spirling, Reference Eggers and Spirling2014). A set of socio-demographic variables like age, gender (using the variable Female that takes the value of one for female delegates), and education (using an ordinal variable that assesses the delegate’s level of education, ranging from zero for those who only attended primary school to five for those who hold a PhD) has been included too.

Finally, we control for other potential confounding factors. First, we identify the affiliation of each MP based on the chamber to which they belong: we include the dummy variables House (equal to one for deputies) and Senate (equal to one for senators), with regional delegates being the omitted category. Second, we include regional dummies to control for the constituency of each delegate, as MPs elected from a given region may decide to dissent or not for peculiar reasons. Third, we control for the number of Facebook friends (FB Friends) that each MPs has. On the one hand, politicians with a higher number of friends can receive more comments (and therefore also more negative comments) than those with a limited number of friends. On the other hand, this measure is also a proxy for popularity and allows us to control for the possibility that Facebook users might be more willing to contact famous and prominent politicians who can be more influential inside the party. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the variables included in the analysis.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

Analysis and results

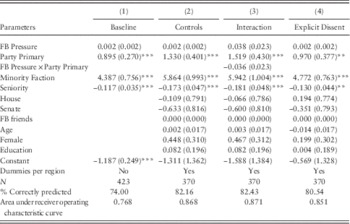

We analyze Dissent, which is a binary dependent variable, using logistic regression. To test our hypotheses, we estimate four models. In Model 1, we include only the variables directly related the competing principals theory. In Model 2, we replicate Model 1 but include all of the controls. In Model 3, we test Hypothesis 2 through the interaction between FB Pressure and Party Primary. Finally, in Model 4 we replicate Model 2 using Explicit Dissent as a dependent variable. Table 2 displays the results. Table 3 provides additional robustness checks by replicating Model 2 using alternative operationalizations of the main independent variable (FB Pressure).Footnote 10

Table 2 Logistic regression of dissent

Standard errors in parentheses.

Significance (two tailed): *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

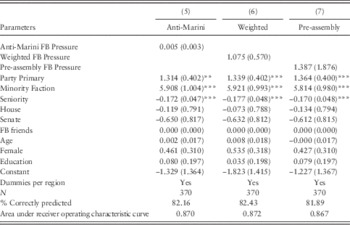

Table 3 Robustness checks: logistic regression of dissent

Standard errors in parentheses.

Significance (two tailed): *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

The results suggest no effect of SNS on Dissent (even when we only consider the dissent publicly expressed on the media). The coefficient of FB Pressure is never statistically different from 0. We can reject Hypothesis 1, as that the pressure exerted by Facebook users did not affect the likelihood that an MP would express dissent from the party line. The interaction term involving FB Pressure and Party Primary is not statistically significant as well. Therefore, contrary to Hypothesis 2, we do not observe differences in the effect of Facebook pressure when we consider delegates selected through party primary or selected by the leadership: in both cases such effect is null.

As such, the public opinion active on SNS does not yet appear to act like a ‘competing principal’, and although SNS potentially allow voters and the rank-and-file to exercise their ‘voice’ (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970), there is no guarantee that MPs will heed their requests.

Conversely, all the traditional ‘competing principals’ seem to matter. First, the electoral rules are crucial. The coefficient of Party Primary is positive and statistically significant, indicating that MPs selected through primary election are more likely to dissent from the position established by the leadership. These MPs are likely to comply with the wishes of another principal, that is, the rank-and-file members in their local constituency. The coefficient of the variable Minority Faction is also consistently positive and statistically significant. Overall, the members of the Renziani faction were loyal to their factional leader, Renzi, who behaved as a real competing principal asking them to defect from the party line. Seniority has a negative and significant effect on Dissent. Despite the secret ballot, the election of the Head of State is a publicly visible, key vote from which voters can infer party unity, in the aggregate, by measuring the overall number of defections or the number of declarations by MPs who express dissent. In such a crucial event, delegates with greater parliamentary experience who have internalized the need for party unity and the mechanisms of party loyalty were less likely to express public dissent in an effort to avoid damaging the party. Finally, none of the other control variables appears to affect Dissent. In summary, these results confirm the findings of the existing literature and extend them from the realm of parliamentary voting behavior to that of the public expression of dissent against the party leadership.

Several robustness checks are provided in Table 3. First, as pressure, we consider only the comments that strictly argue against voting for Marini (Model 5). Second, we report a weighted measure of FB Pressure, that is, the number of user comments promoting dissent divided by the total number of comments received by the delegate over the same period of time (Model 6). Third (Model 7), we measure Dissent and FB Pressure by exclusively focusing on data available before the PD assembly (17 April). None of these changes alters our results.Footnote 11

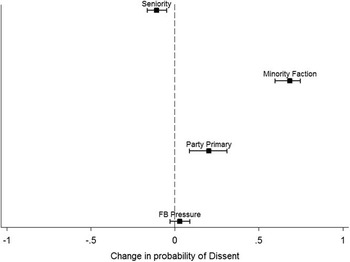

Figure 1, based on Model 1, sheds light on the substantive effects and reports the variation in the probability of Dissent when each continuous independent variable increases by 1 std. dev. from its mean, or when each dummy variable changes from 0 to 1 (while all other variables are held at their means). The effect of FB Pressure is not statistically different from zero, whereas Minority Faction increases the likelihood of Dissent by 68.4 points and Party Primary increases it by 20.4 points. Conversely, Dissent is 43.9 points less likely among more experienced legislators.

Figure 1 Substantive effects of the main independent variables on Dissent.

Discussion

There is an ongoing debate among scholars interested in the relationship between the internet and politics regarding the effect of SNS with respect to accountability, responsiveness and the quality of democracy (e.g. Dekker and Bekkers, Reference Dekker and Bekkers2015). While some scholars argue that SNS can narrow the gap between voters and elected officials, thereby increasing accountability and responsiveness, others hold a more skeptical view. The present paper contributes to this literature by analyzing 12,455 comments posted by the users of SNS on the Facebook walls of Italian MPs to assess whether the pressure exerted on SNS played a role in the selection of the Italian Head of State in April 2013. This election generated a heated debate on the alleged ability of SNS to act as a ‘competing principal’ beyond the party leadership. Several journalists and analysts argued that voters’ and party activists’ comments published on SNS influenced the behavior of MPs, increasing the latter’s likelihood of defecting and sinking Marini’s presidential candidacy. Some of these commentators declared that, for the first time, Italy was experiencing the power of Facebook and Twitter. Conversely, others de-emphasized the role of SNS and stressed the importance of party factionalism and factional loyalties. We solve this puzzle by demonstrating that the pressure exerted online by the ‘activated public opinion’ on PD delegates did not influence their propensity to express public dissent over the candidacy of Marini.

Notwithstanding the risk of inflating the SNS effect (due to the huge amount of pressure exerted through SNS or because Facebook pressure could be endogenous, if SNS users attempt to influence MPs who are already considering the opportunity to defect and just need to be pushed to do that), our findings highlight a null impact of Facebook.

As such, Facebook per se has yet to become a new ‘competing principal’ that politicians must address. Our findings represent unwelcome tidings for those optimistic of the potential of the internet. In autocratic regimes SNS can serve a mirror holding function enhancing demands for democracy and promoting protests and uprisings (Shirky, Reference Shirky2011; Howard and Parks, Reference Howard and Parks2012). Conversely, the ability of SNS to affect democratic political systems by facilitating the interaction between citizens and voters seems, thus far, appears substantially limited, even in a context where SNS allowed citizens to voice and exert substantial pressure.

The results have implications for the role of SNS in enhancing responsiveness and for the understanding of the web as a site for participatory e-democracy and deliberation. Although SNS theoretically provide room for debate and interaction between citizens and elites (followers and leaders), in this case politicians did not feel the need to become responsive to the demands of users of SNS. This could have happened also because MPs were just been elected and therefore the need to show a responsive behavior towards voters was lower; at the same time, MPs felt that the election of the Head of State was a good opportunity to send signals to the leadership in view of the future negotiations around the allocation of office payoffs.

In this regard, our analysis confirms the findings of the literature on party unity, which indicates that the political behavior of MPs is still oriented towards the desires of other and more traditional principals: the party leadership, the MP’s constituency and the party faction.

While we can exclude the possibility that SNS played a direct role in hampering the candidacy of Marini, we cannot test whether, through hybrid logic (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2013), SNS pressure may have affected traditional media or off-line citizens’ dissent. Similarly, we did not consider the impact of off-line protests and private correspondence/SMS. However, their hypothetical effect should not be fully attributable to social media and could be more related to off-line personal contact.

Nevertheless, future research could improve the present study by investigating the effect of SNS across parties and countries and in different environments to evaluate whether social media are indeed changing the power relationship between citizens and politicians or, to the contrary, politics continue as usual.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Alberto Fragapane and Alessandra Cremonesi for their contribution to data collection. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the XXVII Convention of the Italian Political Science Association (SISP), Perugia, 11–13 September 2014. The author thanks the discussant and the participants at that meeting for their useful comments.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2016.14