Introduction

In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro brought to the international fore the need to rethink the processes of economic and social development in terms of environmental sustainability. After three decades, a paradigm shift towards a model of growth which is compatible with the natural resources available and respectful of the ecosystem gained salience once again, and it has been endorsed by international and national initiatives. For instance, the EU Commission allocated a large share of the Next Generation EU to environmental issues and committed its efforts to become a carbon-neutral continent by 2035. Despite such intentions, the specialized literature invariably shows that Western liberal democracies suffer of a lack of effective policies to promote sustainability (Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan, Lenschow, Jordan and Lenschow2008, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010; Baker, Reference Baker2016; Scoones, Reference Scoones2016). The underlying reasons of such deficiencies are manifold, varying from case to case (Bruyninckx, Reference Bruyninckx, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006; Steurer, Reference Steurer, Jordan and Lenschow2008; Heinrichs and Schuster, Reference Heinrichs and Schuster2017; Tingley and Tomz, Reference Tingley and Tomz2020).

Why successful ideas remain under-implemented constitutes a permanent puzzle for policy studies. As noted by Blyth (Reference Blyth2013), a paradigmatic change does not necessarily has a follow up due to political and institutional conditions hindering the entrenchment of a new policy regime. Such an analytical problem has been recently addressed by a strand of literature aimed at understanding the conditions allowing a policy to be viable (Béland and Schlager, Reference Béland and Schlager2019; Patashnik, Reference Patashnik2019; Patashnik and Weaver, Reference Patashnik and Weaver2021). More specifically, these authors stress the idea that choosing the most appropriate instruments to cope with the collective problem is an essential but insufficient feature of a sound a policy design, as political feasibility and endurance represent essential evaluation criteria. In this sense, the traditional attention on whether ideas matter or not can be reformulated in a more specific and testable proposition asking: Under what conditions do ideas have impact in policy-making ushering in durable change?

This contribution aims at answering this question by analysing how and to what extent the paradigm of sustainable development (SD) has been embodied in Italian policy-making at the national level. Italy is nowadays experiencing a new wave of policy-making aimed at institutionalizing the SD paradigm: the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) adopted in 2021 is explicitly committed to push the country towards a ‘radical ecological transition’ and SD. Yet so far Italy can still be considered a remarkable example of failed institutionalization of SD: the process launched at the mid of the 1990s abruptly stopped at the beginning of the Millennium and no significant initiatives in the field were adopted until recent years (Domorenok, Reference Domorenok2019). Hence, a longitudinal study on the previous attempts at institutionalizing such a policy area provides insightful lesson to be learned to incorporate the SD paradigm into effective and feasible policy design and within a structured institutional framework.

From the theoretical standpoint, this work combines the ideational approach (Hall, Reference Hall1993; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith, Reference Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith1993; Surel, Reference Surel2000; Campbell, Reference Campbell2002) with the political system perspective elaborated by Jordan and Lenschow (Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010) for the study of Environmental Policy Integration. We develop a framework which identifies the causal chain linking the ideational dimension of a policy area to the political system where it operates. Hence, we start from the consideration that policy paradigms can sometimes change, but such change can be ephemeral since ideas are likely to be implemented only if they have some potential (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; Genieys and Smyrl, Reference Genieys and Smyrl2017). Our argument posits that ideas do have impact only if the underlying political system underpins them in terms of both political commitment and administrative congruence. Our empirical investigation analyses the initiatives promoted by Italian national governments covering a time span of over 20 years (1992–2020). Using a thick historical description and process tracing (Collier, Reference Collier2011; Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2014) the article shows how the SD paradigm had over time failed to be effectively incorporated in the Italian policy-making due to lack of political commitment, administrative coherence or both. The added value of this effort is twofold: First, it offers an in-depth analysis of the Italian case, which has been understudied to date; secondly, it provides an analytical framework that may travel across ideas and across cases.

The contribution is structured as it follows. In the first section, we introduce the foundations of the analytical framework. Data and method will be presented in the second section. In the third section we engage with the analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the paradigm of SD. The study of the Italian case (fourth and fifth sections) is used to explore the plausibility of our conceptual framework. In the conclusive section, we pinpoint the trajectories of the failed process of institutionalization.

The analytical framework

The ideational approach and the political system perspective

During the 1990s, ‘ideas’ came to be seen as useful tools to investigate both institutional and policy change (Hall, Reference Hall1993; Sabatier and Jenkins Smith, Reference Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith1993; Capano, Reference Capano1995; Yee Reference Yee1996; Campbell Reference Campbell1998). A growing number of scholars stressed how values, beliefs systems, norms, paradigms and frames are relevant factors in shaping decision-makers' positions (King, Reference King2005). While the importance of interests and power relations was not neglected, the inclusion of ideational drivers among policy determinants broadened the established analytic perspectives.

To frame SD in ideational terms, we resort to the concept of ‘policy paradigm’, that is a set of world views, values, principled beliefs and causal representations of reality that decision-makers adopt to define public problems as well as the related policy strategies, approaches and instruments (Hall, Reference Hall, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992, Reference Hall1993; Surel, Reference Surel2000). To date little attention has been paid to the impact of policy paradigms' ideational properties in determining their political fortunes (Blyth, Reference Blyth2002, Reference Blyth2013). We define these properties as the ideational potential of policy paradigms. According to Surel (Reference Surel2000), the constitutive elements of policy paradigms can be placed at different levels. At a macro level, we find the underpinning world views, principled beliefs, norms and values, which represent paradigm's epistemology. At a meso level, we observe the strategies set to achieve paradigm's general goals, including the institutional pre-conditions that are supposed to favour their implementation. Finally, at a micro level the policy instruments and their specific calibration should be identified. By resorting to Sartori's (Reference Sartori2011) logic for conceptual analysis, policy paradigms can thus be placed along a ‘ladder of abstraction’, depending on the internal balance between world views, policy strategies and instruments.

For the policy-maker, such understanding configures a nexus of trade-offs. In fact, the more abstract is the paradigm, the more it will be difficult to translate its logic into policy design. Conversely, as policy-making strategy choose the micro level – focusing on circumscribed programmes – the more it will be difficult to institutionalize specific intervention within a coherent and structured policy area. Hence, the ideational potential of a paradigm refers to the viability of policy ideas. These become ‘programmatic ideas’ (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002; see also Genieys and Smyrl, Reference Genieys and Smyrl2017) when they embody precise guidelines and orientations about how institutional settings and policy instruments should be shaped and mobilized to pursue the paradigm's general goals and strategies, in a large sample of domains of intervention.

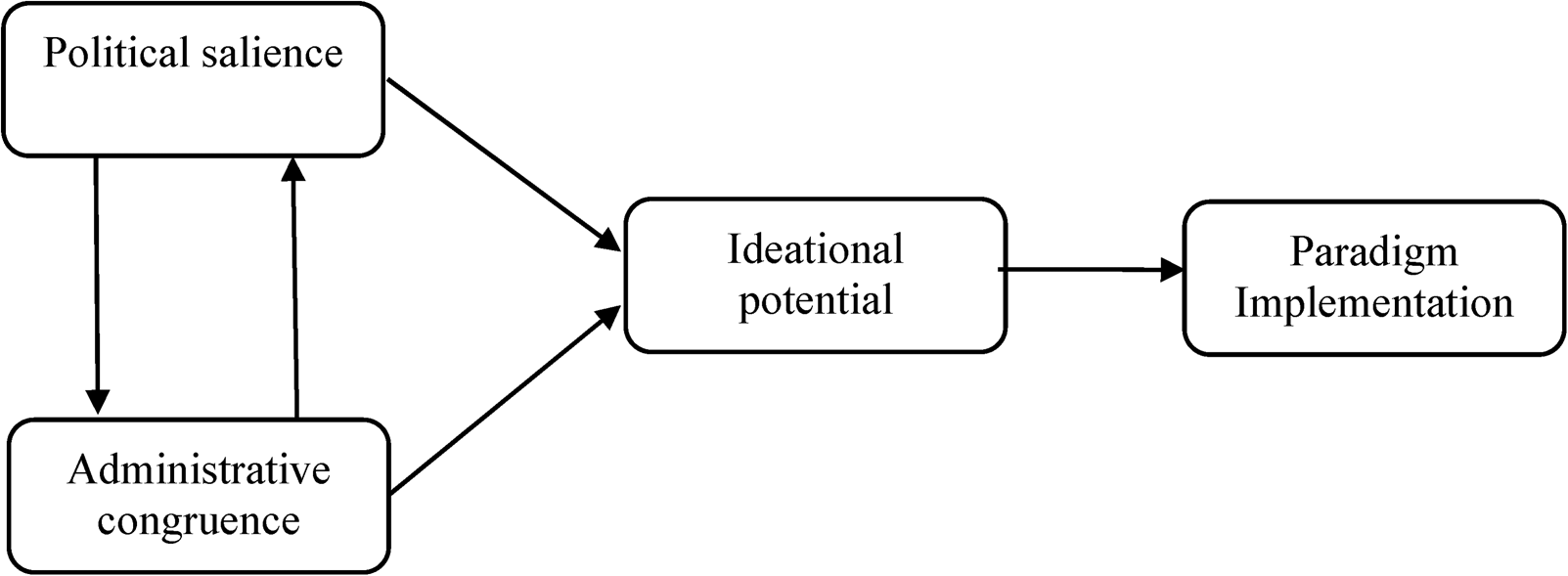

The literature on public policy has shown that the probability that a given paradigm is effectively implemented largely depends on the capacity a given idea has to generate positive feedback among political parties, bureaucratic elites, interest groups and the mass public (Béland Reference Béland2009; Hacker and Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2018; Patashnik, Reference Patashnik2019). Accordingly, the ideational approach in the study of SD could be profitably integrated with a political system perspective (Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan, Lenschow, Jordan and Lenschow2008, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010), which enhances (1) the relevance of cognitive factors and shared societal values in shaping decision-makers' framing process and orientations; (2) the role played by existing institutions; (3) the weight of policy legacies; and (4) the predominant policy preferences. On the one hand the cognitive predispositions of a community limit the range of suitable policy paradigms that decision-makers may consider expendable or appealing; on the other hand, institutional and political constraints mediate the intensity through which actors strive to promote or prevent paradigms in the policy arenas. Figure 1 outlines the nexus between the political system, the ideational potential of a paradigm and the probability that the paradigm is effectively implemented. The main idea is that ideational potential, other things being equal, needs to be politically feasible.

Figure 1. Political system, ideational potential and policy outcomes: a framework.

The contextual factors can be operationalized into two different, albeit interrelated conceptual dimensions. The first, administrative congruence, refers to the degree to which the ideational potential of a paradigm fits with the cognitive and institutional premises of the analysed political system (the prevailing policy paradigms; the organizational set-up of government; the existing administrative practices and traditions). This dimension also includes policy-makers' capacity of building coalitions with societal actors in order to institutionalize a new paradigm (Patashnik and Weaver, Reference Patashnik and Weaver2021). The possibilities that a policy paradigm has to turn into programmatic ideas heavily depends also on its political salience (our second dimension), understood as its attractiveness for the relevant actors of the political system. We maintain that political parties in government are the key actors in promoting the process of institutionalization of a policy paradigm, whose success depends on their attitudes and commitment.

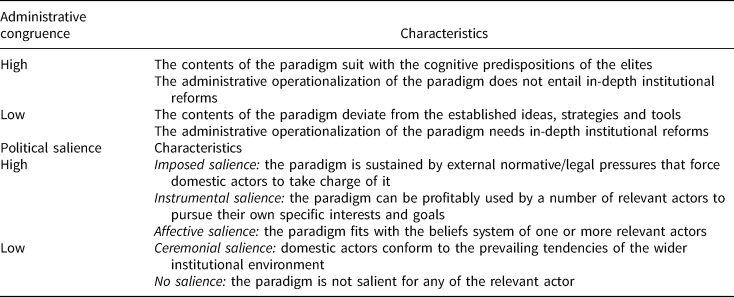

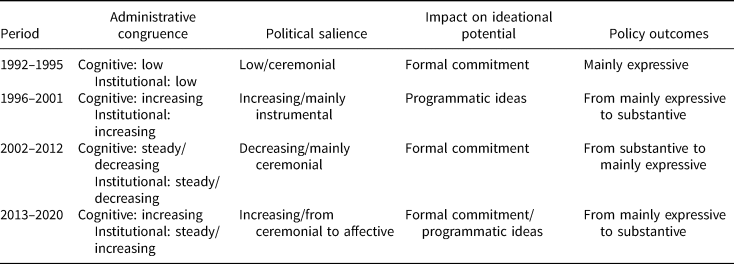

To heuristic aims we distinguish between high and low administrative congruence and political salience. Moreover, since salience varies not only in degree, but also in kind, we also provide a classification of this concept (see Table 1).

Table 1. A classification of administrative congruence and political salience

Combining the approaches

By building on this rationale, our analytical framework rests on the conceptual dimensions previously introduced. Each dimension is considered independent of the others. The analytical framework is built upon a steady representation of policy paradigms and a dynamic configuration of administrative congruence and political salience. Different configurations in their relationships are expected to lead the institutionalization of a paradigm along different paths (Hall, Reference Hall2013). By combining the conceptual dimensions, we obtain a typology of different possible paradigm's development (Table 2).

Table 2. Dimensional configurations' impacts on institutionalization

According to the political system approach, programmatic ideas are likely to emerge when the paradigm is highly salient for the parties in government and its contents are highly congruent with the administrative cognitive pool, the institutional settings as well as the prevailing policy styles and instruments. We argue that a policy paradigm is likely to shape concrete outcomes if both political parties are committed to the realization of the main goals and the administrative system, understood both as bureaucratic structures and the main interest groups, do have resources and incentives to cooperate to reach these goals. If the administrative settings are congruent with the paradigm, but its salience is merely ceremonial or there is a lack of any real political commitment, it will be plausible to observe ideas to be used in bureaucratic politics. That means that such ideas are mainly used by bureaucratic elites to pursue policies on which they have a certain degree of autonomy from politics (Genieys and Smyrl, Reference Genieys and Smyrl2017). Moving to the cells placed on the right side of the figure, if a paradigm is highly salient but poorly congruent in administrative terms, we expect the paradigm to be object of politicization among the main political forces. In this scenario, political parties use ideas to compete for votes thus it is very likely that if a party or a coalition endorse a paradigm their challenger would reject it. When a paradigm is scarcely congruent and salient, we expect to observe formal commitment, providing only symbolic reassurances for those actors interested in the paradigm (Blühdorn and Welsh, Reference Blühdorn and Welsh2007).

Data and methods

By building on Heinrichs and Schuster (Reference Heinrichs and Schuster2017), we argue that the institutionalization of SD can be interpreted as the systematic promotion and implementation of the paradigm in political culture, government structures and administrative procedures, within a given political system. More specifically, we search for the mechanisms related to the above mentioned dimensions, which are likely to underpin the ideational potential of the paradigm, and bring about a paradigmatic shift towards SD. We first introduce the building blocks of SD paradigm to pinpoint its strengths and weaknesses in terms of its institutional and political feasibility: Our reconstruction is based on both primary and secondary sources. The empirical research will then focus on the Italian case, which is considered as a pilot to illustrate some of the main assumptions derived from the comparative literature (Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010; Heinrichs and Laws, Reference Heinrichs and Laws2014; Heinrichs and Schuster, Reference Heinrichs and Schuster2017) and, more specifically, to prove the plausibility of the connections between the building blocks of our framework. The time-span covered by our research starts in 1992 – when a delegation of the Italian government participated in the UNCED – and ends in 2020 – the year preceding the adoption of the PNRR.

The evolution of SD policies in Italy is divided into four temporal sequences: for each temporal sequence we adopt the same analytical scheme as we observe the evolution of both administrative congruence and political salience. Concerning the former, we reconstruct the cognitive predispositions of the policy-makers involved through a combination of information gathered with a qualitative content analysis of primary and secondary sources (see Appendix); and eight in-depth interviews to public officials employed at the Ministry of the Environment, a former Minister of the Environment and national representatives of both Confindustria and Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL). We build upon a qualitative approach based on thick historical description and process tracing (Collier, Reference Collier2011; Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2014). Resorting to process tracing and causal-process observations – rather than variables – allows us to combine the ideational approach and the political system perspectives. The ‘diagnostic pieces of evidence’ (Collier, Reference Collier2011) raised by process tracing provide an in-depth reconstruction of the dynamics leading the analysed process to the observed outcomes (Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2014). Our analysis rests on a thematic matrix (Kuckartz, Reference Kuckartz2014; see Appendix), which allows to identify three fundamental aspects: the prevailing interpretation of the paradigm, its institutional absorption and specific mentions to its practical translation. We integrate this information with an analysis of the Italian institutional and policy context, which is based on primary sources (laws, decrees, plans, ministerial reforms; see Appendix).

The political salience of the paradigm is investigated by resorting to the information provided by the Manifesto Project Database, to verify the extent to which SD is explicitly mentioned in the electoral manifestos (N = 65) of the relevant parties that have participated in the national elections during the analysed period. This will also allow us to assess whether differences in the political composition of the ruling parties in government matter in promoting/hindering sustainability.

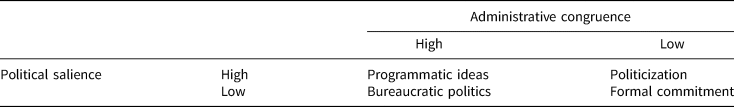

Table 3 provides an operationalization of the two mechanisms scrutinized in line with the literature on process tracing (Beach and Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2014: 112–113): each mechanism is associated with actors and predicted evidence about the direction towards which the mechanism is supposed to operate in order to bring about the expected outcome.

Table 3. Conceptualization and operationalization of the two mechanisms for process tracing analysis

Source: Authors' elaboration, based on Beach and Pedersen (Reference Beach and Pedersen2014: 112–113).

The ideational potential of sustainable development

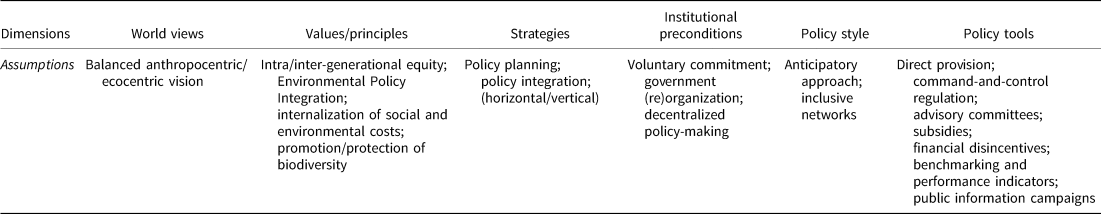

While searching for a precise definition of sustainability may be ‘pointless’ (Adger and Jordan, Reference Adger, Jordan, Adger and Jordan2009), the foundations of SD as a policy paradigm can be identified by analysing its ideational potential (Table 4).

Table 4. The paradigmatic frame of sustainable development

The general consensus on SD can be interpreted as a result of the overall compromissory perspective through which the relationships between human development and the environment have been framed since its launch (Adger and Jordan, Reference Adger, Jordan, Adger and Jordan2009). Until the mid-1980s, the debate on the ‘limits to growth’ tended to place the relations between environmental protection and anthropic systems within a general criticism towards capitalism (Stevis, Reference Stevis, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006; Carter, Reference Carter2021). The issue was framed as a clash of opposite world views, beliefs and values between an ecocentric vision of development and the predominant anthropocentric approach, supporting economic growth (Bruyninckx, Reference Bruyninckx, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006). Over time, this radical contrast has been toned down in parallel to the spread of an environmental consciousness among citizens of advanced liberal democracies (Dobson, Reference Dobson2003; Barnes and Hoerber, Reference Barnes, Hoerber, Barnes and Hoerber2013). These more favourable conditions were conducive for the ascendancy of SD as a policy paradigm. In fact, despite environmental concerns are prior to any other consideration (Lafferty, Reference Lafferty and Lafferty2004), SD aims at keeping together both the anthropocentric and the ecocentric visions of human–environment relationships, by relying on a capitalistic mode of production only constrained by limits to the exploitation of natural resources (Lafferty and Meadowcroft, Reference Lafferty and Meadowcroft2000). The combination between human needs and environmental concerns, along with a specific focus on intra- and inter-generational equity and solidarity, have also imprinted sustainability with a marked ethic connotation (Wetlesen, Reference Wetlesen, Lafferty and Meadowcroft2000): SD is a ‘fundamental normative idea’ (Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft2000: 371) and ‘hardly anybody could be against the basic ideas behind the concept as such’ (Bruyninckx, Reference Bruyninckx, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006: 268).

The governance of SD has always constituted a focal point in the international debate (Adger and Jordan, Reference Adger, Jordan, Adger and Jordan2009; Baker, Reference Baker2016; Domorenok, Reference Domorenok2019; Russel, Reference Russel, Russel and Kirspo-Taylor2022), as ‘sustainability requires cross-cutting structures, introducing new instruments and finally changes in organisational culture and practices that promote the willingness and the ability to innovate organisationally’ (Heinrichs and Schuster, Reference Heinrichs and Schuster2017: 550). Depending on the different interpretations of the core elements of SD, its positive translation into policy strategies and instruments greatly varies (Steurer, Reference Steurer, Jordan and Lenschow2008; Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010). The strategies set to pursue SD rest on two main pillars: policy planning and policy integration. These are associated with a commitment by governments to proceed to a general re-organization of administrative structures towards the decentralization of policy-making processes and cross-jurisdictional coordination, by promoting the active inclusion of non-governmental actors. The orientation towards multi-level governance intertwines with the suggested adoption of a negotiated approach to planning – meaning that national governments are mainly responsible for the coordination of the initiatives promoted from below. Within this framework, the issues related to policy integration – whether vertical or horizontal – arise. Since the policy fields covered by SD are numerous their integration is crucial (Betsill, Reference Betsill, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006; Baker, Reference Baker2016; Howlett, Reference Howlett, Russel and Kirspo-Taylor2022): environmental concerns should inform every single public intervention, while any ecologicalization of the paradigm should be avoided. This strategy implies an effective coordination (and often an in-depth re-organization along new organizational lines) between different bureaucracies, administrative procedures and cultures, which are expected to share general goals and specific objectives (Lanzalaco, Reference Lanzalaco2010).

As for policy style and tools (Howlett, Reference Howlett, Russel and Kirspo-Taylor2022), an anticipatory approach to problem solving is privileged, as well as a clear preference for inclusive policy networks. The inclusion of civil society in the decision-making processes represents another pillar of sustainability (Adger and Jordan, Reference Adger, Jordan, Adger and Jordan2009; Baker, Reference Baker2016): public institutions ought to be supported by a number of actors (such as experts, trade unions, business-firms associations, NGOs, social movements, etc.) to be involved in both policy planning and implementation.

The description provided suggests that, along the ladder of abstraction, the ideational potential of SD can be placed at a rather high level, as little precision characterizes its operational dimensions. While favouring the rapid ascendancy of the paradigm, this vagueness allowed the spread of alternative interpretations ranging from extremely weak to extremely strong approaches to sustainability (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Kousis, Young and Richardson1997; O'Riordan, Reference O'Riordan, Lafferty and Meadowcroft2000; Barnes and Hoerber, Reference Barnes, Hoerber, Barnes and Hoerber2013; Baker, Reference Baker2016). Already at the end of the 1990s, Richardson (Reference Richardson, Baker, Kousis, Richardson and Young1997) claimed that SD was a ‘catch-all definition’, a contradictory idea whose relevance rested mainly on its symbolic and evocative power. Similar conclusions have been reached by a number of scholars over time (Orbán, Reference Orbán2005; Heinrichs and Laws, Reference Heinrichs and Laws2014). These peculiar traits made SD appealing for national governments that mostly used the paradigm as a label to stick to heterogeneous public programmes. According to Blüdhorn and Welsh (Reference Blühdorn and Welsh2007), the formal commitment to pursue SD represented a ‘performance of seriousness’ played by the elites of industrialized countries, which actually adopted a weak or even extremely weak approach to sustainability (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Kousis, Young and Richardson1997; Baker, Reference Baker2016). The symbolic value of the paradigm has overwhelmed its substantive implications indeed. Unsurprisingly, most of the problems faced by SD in its translation into substantive policy outcomes worldwide depend on the puzzling issues of governance (Lafferty, Reference Lafferty and Lafferty2004; Adger and Jordan, Reference Adger, Jordan, Adger and Jordan2009; Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010). First, at the international level, the promotion of SD has mainly rested on agreements of a voluntary nature (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Kehoane and Levy1993; Domorenok, Reference Domorenok2019; Genovese, Reference Genovese2019; Tingley and Tomz, Reference Tingley and Tomz2020). As no binding agreements have been set, each country defined its own model of SD. As a consequence, national administrative cultures and the prevailing policy styles and instruments heavily affected the strategies to pursue SD (Steurer, Reference Steurer, Jordan and Lenschow2008; Jordan and Lenschow, Reference Jordan and Lenschow2010). To complicate matters further, the long-term and cross-sectoral strategies implied by the paradigm impose challenging integration and coordination problems to traditional bureaucratic settings (Heinrichs and Laws, Reference Heinrichs and Laws2014; Heinrichs and Schuster, Reference Heinrichs and Schuster2017). Second, rather than being considered an overarching principle, SD has been largely identified with environmental protection tour court: the ecologicalization of SD has determined the locus of its institutionalization and the types of actors involved (Bruyninckx, Reference Bruyninckx, Betsill, Hochstetleer and Stevis2006). Moreover, this partial interpretation of sustainability restricted its political salience to the Greens' domain, thus hanging the paradigm to the (fluctuating) electoral fortunes of these parties.

The Italian case

The evolution of SD policies in Italy can be divided into four different temporal sequences. The first covers the genetic moment of the process (1992–1995), where the new ideas about SD started to circulate among national policy-makers; the second sequence (1996–2001) saw a rising attention to SD issues, the design and implementation of some programmes and the attempt to institutionalize SD in the national government. Thereafter (2002–2012), governments systematically undermined and occasionally dismantled SD policies up until 2012. The last sequence starts in 2013, when political salience for SD rose once again; this could be taken as the beginning of a new policy cycle, which has been further reinforced with the Next Generation EU and its implementation at the national level.

The systemic transition (1992–1995)

At the beginning of the 1990s, the reflections in the field of SD were rather poor compared to the on-going international debate (Pizzimenti, Reference Pizzimenti2009). According to a later report elaborated by the Italian Institute for Sustainable Development (2005: 47) ‘In the years of Rio, in Italy it did not exist any kind of programmatic platform integrating environmental, economic and social concerns […]’. This backwardness had both cognitive and institutional roots, reflected also at the political level.

As for the administrative congruence of SD at the cognitive level, the Italian environmental underdevelopment (Pridham and Konstadakopulos (Reference Pridham, Konstadakopulos, Baker, Kousis, Richardson and Young1997); Freddi, Reference Freddi, Di Palma, Fabbrini and Freddi2000) was a well-known reality. The bureaucratic elites have always been uninterested in the environmental consequences of socio-economic policies (De Benetti, Reference De Benetti1995; Lewanski, Reference Lewanski1997) since ‘growth at any cost’ was perceived as the main goal of development policies (Ginsborg, Reference Ginsborg1996). In 1989, the Minister for the Environment maintained that ‘[…] there is a cultural resistance against the acceptance of the concept of SD’. From an interview with a public official (PO1) at the time employed at the Ministry for Environment (MA): ‘At the MA sustainability was perceived as a marginal issue belonging to the abstract category of ethic: something that could put the brakes to development’. Sustainability was mainly framed as an environmental constraint to development, something that ‘should have been included’ in the official documents in homage to the international debate. Another public official interviewed (PO3) claimed: ‘[…] the idea was scarcely rooted within the Ministry, there was a lack of expertise: it was a cultural gap […]’. The bureaucratic elites were not the only collective actors scarcely committed to sustainability. Other relevant players in the field of development policies – such as Confindustria and the major trade unions (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (CGIL), Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori (CISL), Unione Italiana del Lavoro (UIL)) – contributed to marginalize the paradigm. From the analysis of the documents adopted by both Confindustria and the trade unions in the period, it clearly emerges how sustainability was perceived as an ‘environmental constraint’ to development. This is what the national coordinator of the Department for Environment and Territory of the CGIL told us during an interview (TU1): ‘Trade Unions are strange animals: we have fought glorious battles for workers' health and safety, but when the problem of environmental impact of industrial policies arose there was a ‘closure’’.

This widespread cognitive aversion combined with enduring institutional limits as it coupled with the absence of any theorization about which role the State should play in regulating economic development (Valli, Reference Valli1998). The Italian economy was characterized by a huge territorial unbalance between northern and southern regions, which brought governments to adopt different strategies that turn into structural distortions (Bagnasco, Reference Bagnasco1977); moreover, economic development was underpinned on the widespread diffusion of family-lead micro enterprises, which hindered innovation and any top-down coordination efforts (Trigilia, Reference Trigilia1986). Hence, there was a lack of consolidated administrative structures aimed at promoting economic and territorial planning (Ministero dell'Ambiente, 1989), while an extreme fragmentation of institutional responsibilities characterized the policy fields embraced by SD – as the Inter-ministerial Committee for Economic Planning (CIPE) was a marginal agency managed by the Treasury. Within this picture, the MA was created in 1986, but it was not provided with effective powers nor sufficient human or financial resources (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani1998). The sudden ecologicalization of sustainability represented the easiest way to marginalize the paradigm. From an organizational point of view, the Ministry was not conceived to favour horizontal coordination among institutional actors, as it was built upon ‘[…] hierarchical ‘generalism’ and transitive asymmetry […], along logical-deductive guidelines’ (Freddi, Reference Freddi, Di Palma, Fabbrini and Freddi2000: 414 our translation). A public official of the MA (PO2) on this point: ‘[Environmental policy was] characterized by a massive and confused legislation, a lack of implementation and low levels of enforcement’. Policy interventions were mainly reactive and poorly coordinated (Diani, Reference Diani1988; Lewanski, Reference Lewanski1997), and the relating policy networks were rather closed, in the absence of any form of consultancy with non-institutional actors.

Concerning the political salience of SD, the collapse of the established political system between 1992 and 1993 (Jones and Pasquino, Reference Jones and Pasquino2015) complicated matters further. The already limited attention towards sustainability almost vanished from the political discourse, being the Green Federation (Vannucci, Reference Vannucci, Bardi, Ignazi and Massari2007) politically isolated. Indifference was well represented by the references to the paradigm reported in parties' manifestos, in both 1992 and 1994 general elections. Data derived from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, Regel, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2022) show that, in 1992, among the nine relevant parties for which manifestos are available, only in four cases SD is explicitly mentioned. Things further worsened in 1994. In the manifestos of the eight parties analysed, only two contain explicit references to sustainability.

Towards sustainability? (1996–2001)

In the second half of the 1990s, the process of institutionalization of SD unexpectedly accelerated by following the changing orientations in both development and environmental policies promoted by centre-left governments, in power from May 1996 until the end of the legislature. At the cognitive level, the administrative congruence of SD increased as the government and the bureaucratic elites, as well as Confindustria and the trade unions, adopted a rather different approach. In his inaugural speech, the Prime Minister R. Prodi called for the need to promote ‘an effective and civil capitalism’ in the name of ‘economic democracy and SD’. An ecologist, E. Ronchi, was appointed as Minister for the Environment, to give new impetus to environmental policy and to favour the administrative ‘absorption’ of environmentalism. During an interview, Ronchi told us that ‘[…] I would not say that there was a radical change in the policies promoted by the government. I may say that a debate began […]. To some extent these issues entered into the institutional agenda’. Also, Confindustria relaxed its past hostility by increasingly asking for the introduction of fiscal tools rewarding firms' virtuous behaviour, as well as for the promotion of environmental certification schemes and ecolabels. As confirmed by a top level representative of Confindustria (CO1) ‘The positions we represent are multifaceted, the approach to the issue is complex. In theory, we can only be in favour of SD, because we are all aware that the territory where we produce must not be defaced […]’. The trade unions improved their relations with the ecologist movements, pledging towards an in-depth integration between socio-economic and environmental concerns. From the proceedings of a national seminar held in Rome by the CGIL, in April 1996: ‘[…] for the first time, the Trade Unions bind their economic policy proposals to environmental concerns, which are seen as concrete opportunities to create new employment’.

The administrative congruence of the paradigm (at least apparently) increased also at the institutional level. The policy transfers (Page Reference Page2000) coming from the EU favoured the progressive absorption of general guidelines, organizational and managerial practices, techniques and tools set for the planning of structural funds (Fargion et al., Reference Fargion, Fargion, Morlino and Profeti2006). The so-called ‘New Planning’ (Viesti and Prota, Reference Viesti and Prota2004) was based on the principles of sustainability, consultation and inclusiveness of decision-making processes. Moreover, the 2001 Constitutional ReformFootnote 1 included the environment among the foundational values of the Republic, by fixing a two-tier regime of ‘concurring responsibilities’ in the promotion of sustainability. In both the development and environmental field, the approach centred on the (ill-defined) role of the State shifted towards the regionalization of competences. The government was supported by the National Agency for Environmental Protection (ANPA) and was provided with general regulative and coordinating powers. Regions were responsible for the promotion and implementation of SD policies and were empowered – albeit through a confused and patchy approach (Freddi, Reference Freddi1997; Reference Freddi, Di Palma, Fabbrini and Freddi2000) – with a network of Regional Environmental Protection Agencies (ARPAs). At the same time, the MA gained an unprecedented political role. Ronchi promoted changes in environmental policy strategies, style and instruments (Pizzimenti, Reference Pizzimenti2008); most important, in 1999 the Minister pushed for an in-depth organizational reform of the Ministry,Footnote 2 which was assigned increasing resources and expertise (La Camera, Reference La Camera2005). A number of leading figures of Italian ecologism were appointed in relevant ministerial posts, as well as in the public institutions supporting the MA.

Concerning political salience, during the 1996 electoral campaign parties had already shown an increasing interest towards sustainability: by analysing the manifestos of nine relevant parties, five explicitly mentioned sustainability (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, Regel, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2022). Furthermore, the participation of the Green Party in the national government was conducive. Its coalition potential somewhat forced the other governing parties to converge on the issues raised by ecologism. The political salience of the paradigm among parties in government thus shifted from merely ceremonial to a peculiar mix of (mainly) instrumental and (limited) affective salience.

Backlash and crisis (2002–2012)

This phase is characterized by both political instability and economic crisis. After the governments led by S. Berlusconi (2001–2006), the 2006 general elections were won by a centre-left coalition, but the lack of any stable majority brought to early elections in 2008, when a new centre-right government was formed. To complicate matters further, since 2009 Italy was heavily hit by the world economic crisis (OECD, 2012). As far as the crisis worsened during 2010–2011, EU institutions fastened their pressing on the Italian government to adopt drastic measures for deficit containing and economic restructuring. In November 2011, the new ‘technical’ government lead by former EU Commissioner M. Monti decidedly addressed financial and economic issues, while development and environmental policies were declassified.

Concerning administrative congruence at the cognitive level, the centre-right governments led by S. Berlusconi openly pledged ‘to break up’ with the policies launched by their predecessors. The ‘blue environmentalism’ (Pizzimenti, Reference Pizzimenti2009) promoted by the government rested upon the traditional paradigm of economic growth ‘at any cost’. The parliamentary sessions dedicated to the approval of the Kyoto Protocol, in sight of the 2002 Earth Summit in Johannesburg, were indicative of a simple ‘performance of seriousness’ (Blüdhorn and Welsh, Reference Blühdorn and Welsh2002). Berlusconi publicly declared that he preferred to speak of ‘durable development’, since sustainability was a concept too difficult to understand.Footnote 3 Confindustria's approach was perfectly in line with that of the government, which on the contrary was harshly criticized by the Trade Unions. While the position of the former was open to SD albeit ‘[…] respecting the real development needs of the territorial economies’, the latter intensified their commitment to promote sustainability, which was considered an ideational ‘lock pick’ to claim for more inclusiveness of the policy-making process. As reported in a 2006 joint press release ‘Concerning problems relating to both democracy and equity of development processes the policy making can no longer be limited to traditional actors, but it should involve those subjects that have been traditionally excluded […]’.

Also administrative congruence at the institutional level decreased. The role of the MA was subordinated to that of other ministries and most of the leading figures appointed by former Minister Ronchi were removed. In this respect, a public official (PO2) told us that ‘From 2002 onward the environmental policy has been managed by the Prime Minister, the Minister for the Infrastructures and those for the Industry and the Treasury: The Minister for the Environment has been subordinate and inadequate’. At the end of 2002, a new lawFootnote 4 introduced significant changes in the competences and organization of the MA. The organization based on departments, which had been introduced in 1999 (but never implemented), was replaced by a new one founded on six general directions supported by specialized agencies (Associazione per la Protezione dell'Ambiente e per i servizi Tecnici (APAT), Energia Nucleare Energie Alternative (ENEA) and Istituto Centrale per la Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica applicata al Mare (ICRAM)). However, in 2006, departments were re-introduced and the MA modified its denomination.Footnote 5 As reported in the 2006 annual report of the Corte dei Conti (Vol II: 29–30, own translation):

Undoubtedly, the continuous reorganization process that has been involving the Ministry for some years generates a series of critical issues. […] We cannot but notice how the continuous rethinking of the structure, the consequent redefinition of internal skills as well as the aggregation and disaggregation of the offices determines a situation of objective ‘operational instability’.

Oddly enough, in 2007, a new law modified again the internal articulation of the MAFootnote 6 and the general directions were restored. Moreover, the government created new environmental agency – ISPRA,Footnote 7 by the merge of APAT with two other research institutes, to the aim of coordinating the ARPAs while supporting the MA for technical and scientific consulting. Finally, in 2009, a new reform empowered the role of the General Secretary of the MA with coordination powers.Footnote 8 In a recent interview with a public official currently employed at MA (PO5): ‘the MA has always been a ‘Cinderella’ Ministry, its constant reform was the consequence of an extensive resort to spoil system: each appointed individual used the administrative structures fluidly’.

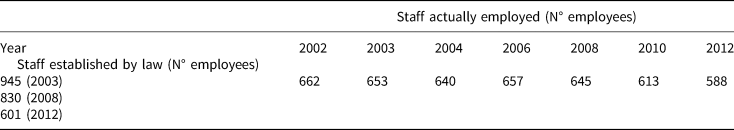

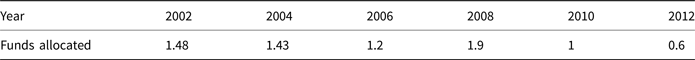

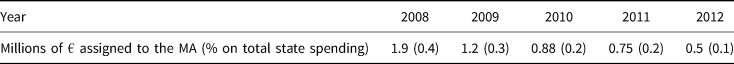

Repeated government changes and the continuous organizational reforms hindered the operative capacities of all the ministries involved in development policies. In the case of the MA, the lack of any established legislation concerning spending made the planning of new interventions difficult (Corte dei Conti, 2003). The long-standing inadequacies were further worsened by the unintended consequences of the administrative decentralization process. While, at the theoretical level, the cooperative federalism introduced in 2001 should enhance both coordination and integration in policy planning activities, in practice ministries' implementation capacity was limited as a number of programmes were now primarily managed by decentralized administrations. This turned into ‘[…] complex and inefficient decision-making processes [and] problems relating to coordination between different levels of government […]’ (Corte dei Conti, 2013). The organizational fluidity of the MA reflected also into a clear resizing of its human and economic resources. As the series of data provided by the annual reports of the Corte dei Conti show, if compared to the staff formally assigned by law, the number of employees actually in office was much lower, and it sharply decreased during the decade – in particular after the s.c. ‘spending review’ process (Table 5). This contraction ran in parallel to financial cuts: the amount of funds allocated to the MA in 2012 was more than halved compared to 2002 (Table 6).

Table 5. Number of employees at the MA (2002–2012)

Table 6. Funds allocated to the MA (2002–2012) – millions of Euros

The political salience of SD followed a disjointed pattern in the period. During the 2001 electoral campaign, none of the four parties that formed the winning coalition ‘The House of Freedom’ mentioned sustainability in their manifestos (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, Regel, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2022). In their ‘Program for a Legislature’, the concept of development was declined in the following terms:

[…] the prerequisite of any redistribution policy and modernization is development, which may only come from creative freedom, capacity for initiative, innovation, research and employment. In Italy all these energies have been hindered and mortified by archaic ideas. […] A fundamentalist and irrational ecologism prejudicially blocked all major infrastructures.

In 2006, the winning centre-left coalition (including the Greens) was explicitly committed to pursue sustainability, while no mentions were made in the manifestos of its centre-right counterpart (Lehmann et al. 2022). In 2008, references to SD could be found only in one electoral manifesto (that of PD) out of five: the winning centre-right parties did not mention SD at all. Finally, in the years of the technical government (2011–2012) ‘The issue of SD definitely downscaled in the domestic political agenda as a consequence of the economic crisis […]’ (Domorenok, Reference Domorenok2019: 69).

The beginning of a new policy cycle? (2013–2020)

This last phase registers an apparent reversing trend, since an increasing attention towards SD has progressively intertwined with administrative reforms that should facilitate the institutionalization of the paradigm in the years to come. However, significant differences in the political orientations of the five governments in power (following the 2013 and 2018 elections) turned into different approaches. In this respect, at cognitive level the positions of the government lead by M. Renzi (2014–2016) still reflected the prevailing ceremonial orientations of the recent past. In an interview given in 2016, the PM maintained that Italy ‘[…] must have a development model that rejects an ideological and non-operational environmentalism; however, [Italy should be] at the forefront of a sustainable development model able at combining business, the environment and the future of the new generations’. Differently, the second executive led by G. Conte (2019–2021) was much concerned with the promotion of SD. In his inaugural speech, PM Conte made repeated references to SD as an overarching principle to pursue in policy planning.Footnote 9 In 2020 the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASVIS) appreciated that the government openly pushed to include references to sustainability into the constitution.Footnote 10 At the same time, interesting signals of an increased awareness among socio-economic elites can be identified. After organizing a conference on ‘Sustainability and firms’ social responsibility’, the CGIL adopted a manifesto in which it was stated that ‘Sustainability risks to become an empty word if it is not embodied in every aspect of our political line and if it is not lived and practiced in the categories and platforms that we build’. Similarly, in an official document issued by CISL, in 2015, it was argued that ‘the environment can no longer be considered a marginal or sectoral issue for practitioners, nor just a chance for green deals in the new business of green economy’. Even Confindustria adopted a ‘Chart of sustainability principles’, which constitutes a valid indicator of an enhanced attention to these issues, while in 2019 the organization began to publish an annual ‘Sustainability Report’.Footnote 11

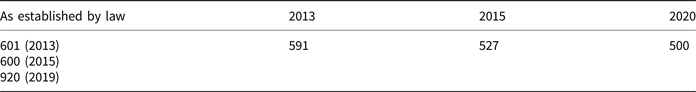

In institutional terms, it was crystal clear that the cooperative federalism introduced in 2001 had produced ‘[…] a serious implementation failure of environmental policies at the local level, with widespread and dangerous “intervention gaps” that are turning into onerous sentences imposed by the Court of Justice of the EU’ (Corte dei Conti, 2015). On a total of 86 sanctions inflicted to Italy in 2020, 21 concerned environmental policy, by far the most affected sector (Corte dei Conti, 2020). At the same time, the MA continued to show structural deficiencies in terms of technical expertise and dedicated personnel, by resorting to Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) and Società per la Gestione degli Impianti Idrici SpA (SOGESID SpA) for assistance. In this respect, in 2018, the government authorized the recruitment of 420 employee units in the following three years,Footnote 12 by reversing a trend of continuous cuts launched in 2003 (Table 7). However, also because of the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, in 2020 the recruitment process was not yet operative (Corte dei Conti, 2021). More in general, a new organizational reform of the MA was approved in 2019.Footnote 13 The General Secretariat was abolished while two macro-departments were created, which were further articulated into general directions (tot. 8). Leaving aside any consideration about the umpteenth reform of the MA, it must be noticed that while in 2013 the effects of the economic crisis still had great impacts on the spending strategies of the government, in the following years the amount of funds allocated to the MA increased, by reaching the same values as in 2008 (Table 8).

Table 7. Number of employees at the MA (2013–2018)

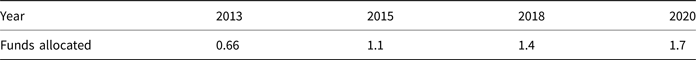

Table 8. Funds allocated to the MA (2013–2020) – millions of Euros

Concerning the political salience of SD, mentions to sustainability can be found in the manifestos of all the eight parties that won parliamentary seats in 2013: in many cases it was declined in specific terms (such as urban mobility, renewable energies or sustainable growth), while in two cases (the Partito Democratico (PD) and the extreme-right Fratelli d'Italia (FdI)) the reference to SD as a whole was explicit. Sustainability assumed a mainly ceremonial salience for the parties that formed the subsequent overarching governmental coalition, to comply with the objectives set by the UN 2030 Agenda. In 2018, among the most relevant parties, it must be noticed how positive references to SD were absent in the manifestos of both Forza Italia and Lega (the latter in government until 2019), being Fratelli d'Italia the only right-wing party mentioning SD. The Movimento 5 Stelle (the most voted party) was by far the party most committed to SD, showing a mainly affective salience; it was followed by leftist Liberi e Uguali (LeU) and other centre-left parties (PD, Italia-Europa Insieme and +EU); also centrist parties mentioned SD in their manifestos (Lehman et al., Reference Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, Regel, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2022). References to SD were included also in the ‘Government Deal’ signed by M5S with Lega (2018); as well as in the ‘Government Program’ signed by the M5S with PD and LeU (2019).

The policy outcomes (1992–2020)

We now turn our attention to the main changes in the policy outcomes, that is those initiatives expressly referred to SD adopted by Italian national governments in the analysed period. Table 9 summarizes the main trajectories followed.

Table 9. Summary of findings

During this first sequence, the poor administrative congruence of the paradigm and its limited political salience were conducive factors for mere formal commitments (Pizzimenti, Reference Pizzimenti2008). Governments aligned with the objectives set at the UNCED and the further steps taken by the EU through the V Environmental Action Program. In July 1992, the Parliament approved at vast majority a non-binding resolution concerning SD. The only policy outcome adopted was the National Plan for Sustainable Development (PNSS), elaborated by the MA in collaboration with technical agencies (ENEA and Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (ENI) Foundation), and approved by the CIPE at the end of 1993. The cultural suspicions towards sustainability were well represented by the definition formulated in the Plan: ‘Sustainable development does not mean to stop economic growth’. The contents of the PNSS consisted of a ‘cut and paste’ from both the Agenda 21 and the V EAP. A public official at the time employed at the MA (PO2) told us that:

The Plan was very naive and experimental. During its formulation a number of crucial mistakes were made. First, we indicated a number of policy objectives and related instruments to be adopted by other Ministries: this made the plan politically impracticable […]. Moreover, the objectives were far from being specified […]

All in all, the PNSS was a sort of ‘exercise in style’ in compliance with Rio: its actual possibilities to turn into substantive policy outcomes were almost null (La Camera, Reference La Camera2005). A few years later, during a parliamentary session dedicated to SD, a MP argued that ‘[…] all the colleagues agree that the PNSS largely remained on paper as a mere enunciation. There was a huge inertia in its implementation by all the Ministries and no harmonization […] among environmental policies and other policy fields […]’.Footnote 14

The second sequence (1996–2001) both the administrative congruence and political salience of the paradigm increased, and some attempts to institutionalize the policy took place. Within this framework, a number of substantive policy outcomes were adopted. The guidelines set by the centre-left governments followed two patterns: institutional strengthening and financial incentives. Focusing on the former, the goal of integrating environmental issues in all policy fields was pursued by creating (1998) a Sustainable Development Commission (CSS) at CIPE. The CSS was both a political and technical organ, formed by representatives indicated by different ministries. The following year, the ENEA was assigned the role of National Agency for Sustainable Development and an organizational reform of the MA was launched,Footnote 15 which introduced a Department for Sustainable Development and Staff Policies (DSS). The DSS was provided with powers for the promotion and coordination of SD projects as well as for conceiving and spreading tools and technical information for their implementation. At the same time, the ENEA and the MA started drafting a National Strategy for Sustainable Development (SNSS), through the inclusion of a number of institutional and non-institutional stakeholders in the National Consulting Forum for Sustainable Development. A Public Official (PO3) employed at the MA told us that ‘[…] the process set to approve [the SNSS] was based on the principle of participation […]. It was a participated and mediated drafting’. A Task Force was created by the DSS to the aim of helping Regional Environmental Protection Authorities (ARPAs) to improve their skills (La Camera, Reference La Camera2005). The DSS explicitly addressed the problem of the technical deficiencies of the ARPAs by ‘injecting’ 150 experts in their structures, to encourage learning processes. After the re-organization of the MA, in 1999, the DSS was absorbed by the new General Direction for Sustainable Development. The at the time General Director (PO4) confirmed that ‘we did not have a large budget, but we gained relevance anyway: when I was appointed there were just 20 employees, when I left more than 200 people were working for sustainability […]’. These institutional innovations were not the only substantive outcomes on the road to sustainability. In fact, a number of measures financing Local Agenda 21 projects were promoted by the MA through public calls, in 2000. Although the total amount of resources co-financed by the Ministry was quite limited, it represented a first substantive support to the Local Agenda 21 network. Moreover, at the end of that year the government established a specific Fund for Sustainable Development (FSS), which should be managed by the MA: the overall budget allocated amounted approximately to €129 million, to be allocated in the following three years (Pizzimenti 2009) (Table 10).

Table 10. Funds allocated to the Mission 18 ‘Sustainable Development and protection of the territory and of the environment’ (2008–2012)

During the third sequence (2002–2012), while administrative congruence decreased at both cognitive and institutional level, the few traces of instrumental salience faded away which was replaced by a renewed ceremonial attitude. The mainly expressive nature of the policy outcomes emerged since 2002, when the annual report of the Corte dei Conti stated that, despite government's formal commitment ‘[…] the administrative guidelines and the qualifying goals do not emerge clearly to the purpose of identifying public policies […]’. Berlusconi's government was somewhat forced to adopt the SNSS it had inherited, in compliance with the international agreements. A public official (PO1) reported that ‘the new government has maintained the commitment to adopt the SNSS in sight of Johannesburg […]. But the process ended up there: the mechanisms set by the SNSS have never been implemented […]’. This state of affair lasted also in the following years, when the main initiatives adopted were in compliance with the Kyoto and Montreal protocols, while the administrative organizational fluidity of the MA was conducive in hindering any reliable planning activity in the field. In 2006, the Corte dei Conti stressed how ‘[…] the launch of a general revision and reorganization of the Ministry, which is still in progress, and the redefinition of the guidelines relating to the institutional missions and the activity programs of the ministerial structures, have contributed to a slowdown in the achievement of its goals’. The removal of the directors appointed by Ronchi had a negative impact on the continuity of the on-going interventions, many of whom – like the FSS or the public calls to promote Local Agenda 21 – were no longer financed. An interest towards SD seemed to revive in 2008–2009, at least on paper. The (re)introduction of a Direction for Sustainable Development, Climate and Energy (2008) ran in parallel to an overall change in the structure of the State budget, which was organized along ‘missions’ and ‘programmes’: mission n° 18 was explicitly devoted to Sustainable Development, territorial and environmental protection, within which the programme n° 5 was dedicated to Sustainable Development. The relating competences were assigned to the MA, the Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MISE) and the Minister of Finance. In practice, however, the MA was the only responsible in the management of the mission, as it received more than 2/3 of the total funds allocated from the State budget. Moreover, despite the re-activation of a Fund for Sustainable Development, ‘[…] the complexity of the procedural iter preparatory to the operational start-up of the Fund, resulted in a postponement of the implementation process and the allocation of financial resources’ (Corte dei Conti, 2009). The complete ‘ecologicalization’ of SD brought to its progressive marginalization, which followed the decaying fortunes of the MA during the years of the economic crisis. In Table 6 it is possible to observe the cuts made to mission n° 18, from 2008 to 2012: as a consequence, also the funds assigned to programme n° 5 sharply decreased (from €300 million in 2008 to €68.34 million in 2012).

The final sequence (2013–2020) registers a renewed interest towards the paradigm: both the administrative congruence and the political salience of SD increased, in particular during the years of the governments led by the M5S – for which SD had an affective salience. Policy outcomes thus change from mainly expressive to substantive. Until 2015, the only policy outcome adopted was the Sustainable Consumption and Production plan oriented to improve Green Public Procurement among public agencies – which was an initiative of an administrative nature (Domorenok, Reference Domorenok2019). The funds allocated to Mission 18 remained rather stable during the first two years (Table 11), when Italy met the goal of the 6.5 reduction of gas emission set in the Kyoto protocol, although by buying emission units from Poland (Corte dei Conti, 2016). Most importantly, in 2015, the drafting of a new SNSS began. The process was managed by the general direction for SD (led again by the General Director in office in 2000) through an inclusive approach and ended two years later. According to our interviewee (PO5), a collaboration with CIPE (renamed CIPESS, the ‘SS’ standing for ‘sustainable development’) brought to the adoption of the new National Strategy in 2017. This programme heavily relies on the active involvement of the regions: thus, in April 2018, a national ‘round table’ was organized to define a shared pattern that would lead regional governments to adopt their own strategies, within the general framework set by the MA. At the end of 2018, a national conference on SD was held in Naples, which launched a National Forum: a public call then followed (April 2019), to involve the highest number of actors of the civil society to be included in the working groups of the Forum, whose activity began in December 2019. The 185 actors who adhered to the Forum then participated in the preparatory work set for the three-year revision of the National Strategy, originally planned in March 2020 and then postponed due to the pandemic crisis. During 2020 – when we register the highest allocation of funds ever to Mission 18, now absorbing the 92.2% of the total funds assigned to the MA (Corte dei Conti, 2020) – a number of new initiatives were promoted, the most relevant being the ‘Policy coherence for sustainable development: mainstreaming the SDGs in Italian decision-making process’ (PCSD). The project has been financed by the European Commission within the Structural Reform Support Program 2017–2020: in this respect, the Ministry cooperates with the DG Reform and Organizzazione per la Cooperazione e lo Sviluppo Economico (OCSE) to promote the inclusion of different actors in the definition of a National Action Plan for the coherence of SD policies, to successfully implement the National Strategy.

Table 11. Funds allocated to the Mission 18 ‘Sustainable Development and protection of the territory and of the environment’ (2013–2020)

Conclusions

While SD is once again a worldwide mainstream idea, its actual and sound implementation continues to stand still. The literature on public policy has repeatedly identified that the political system – understood as the actual arenas of parties, bureaucracies and interest groups – is crucial for the institutionalization of a given policy. In this vein, this article advanced a framework based on two dimensions of the political system which are deemed to have an impact on the ideational potential of SD as a policy paradigm.

The framework has been used to trace the hows and whys that could help explaining the failed institutionalization of SD in Italy, trying to uncover political system rooted mechanisms that hollowed out such a paradigm. Our empirical research was based on thick historical description and process tracing. The time span covered (1992–2020) has been split into four different phases to assess which configurations of cognitive, administrative and political conditions could be observed. Like most industrialized countries, also in Italy the rather vague paradigm of SD has largely represented a non-binding reference for national governments, who paid a sort of ‘lip service’ to sustainability without translating this commitment into substantive policy outcomes. Predispositions concerning the need to entrench SD in the organizational set-up of government have always been rather weak. Yet, the 1996–2001 legislature and the 2013–2020 period register policy programmes inspired by the SD paradigm and the institutionalization of the agenda had been attempted. This policy change actually suggests that one of the dimensions, even if isolated as the rise of political salience, brought about some impacts. Yet, the national government mainly produced institutional change through continuous organizational reforms, while resource mobilization has been overall limited and delayed. This may be interpreted as an indicator that both the dimensions of the political system are necessary for an effective institutionalization of the new paradigm, since only the lack of administrative capacity was sufficient to jeopardize the institutionalization of a new paradigm, even when its political salience turns from ceremonial to instrumental or affective.

However, the established structural deficiencies impose a general reflection on sustainability as a programmatic idea at large, since its global failure so far can no longer be counterbalanced by a favourable narrative. Due to political instability and the severity of two economic crises (in 1992 and 2008) the case of Italy was a hard one for a paradigm shift towards SD and thus the failed institutionalization of it is not a surprise. Though, the case is interesting because it shows that, despite incoherently, attempts of policy change have been pursued and some policy outputs produced. Moreover, and consistently with the recent literature on policy feedback, the backlash occurred since 2002 suggests that the strategies policy-makers deployed to change the status quo were inadequate since they forgot to anticipate positive feedback among institutional and societal stakeholders. In this vein, further research is needed to uncover which strategy actors should adopt in ‘hard’ context for the implementation of SD, namely those lacking political salience, administrative congruence, or both. This appears absolutely relevant in a moment characterized by abundance of resources such as those made available by the Next Generation EU through the PNRR.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.6.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.