Introduction

“There is not in Europe a better station to collect intelligence from France, Spain, England, Germany, and all the northern parts, nor a better situation from whence to circulate intelligence through all parts of Europe, than this,” wrote the American revolutionary John Adams of the Dutch Republic in 1780.Footnote 1 As Adams and many of his contemporaries knew, the Dutch Republic was the heartland of information production and dissemination in eighteenth-century Europe. Yet very few scholars have investigated the role of the Dutch Republic in the collection and dissemination of intelligence during the eighteenth century, overlooking its significance to the history of the Dutch Republic, early modern Europe, and the revolutionary Atlantic.

The primary explanation for this knowledge gap is that the Dutch eighteenth century has taken a peculiar place in the historiography of the Dutch Republic and early modern Europe more broadly. Traditionally, scholars understood the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic as a “republic in decline,” a poor facsimile of the glorious Golden Age of the seventeenth century that deserved little scholarly attention beyond analyses of its downfall. Melancholic contemporary accounts on the political state of the Dutch Republic combined with the numbers on the eighteenth-century Dutch economy have largely substantiated their claims that the Dutch Republic was no longer among the world's prominent powers, as it had been during the seventeenth century.Footnote 2 Scholars even prefer to link the revolutionary era of the 1780s and 1790s—the most studied decades of the Dutch eighteenth century—to the history of what R. R. Palmer called “democratic revolutions” that continued into the nineteenth century.Footnote 3

Although this view remains common in larger historical narratives and popular perceptions of the period, scholars have increasingly argued for the significance of the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic, despite its relative decline. These scholars have demonstrated that the Dutch Republic in the eighteenth century remained a global centre of finance capitalism, a significant staple market of European and colonial goods, as well as an intellectual hub of Enlightenment and revolutionary thought.Footnote 4

Accepting the premise that the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic was more than a “republic in decline,” what do we make of Adams’ assessment? Why was the Dutch Republic an important place for intelligence gathering and dissemination in eighteenth-century Europe? How was this information acquired, produced, and spread? Who was involved in intelligence gathering and what were their effects on the Dutch Republic and the larger Atlantic World? Surveying previously underexamined British and American intelligence networks in the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic reveals that the Republic's favourable geographic location, its postal services, its sophisticated press, and its mercantile economy made it an ideal place to extract information and build intelligence networks for global empires as well as emerging powers. These preconditions, combined with the Dutch Republic's political proximity to Great Britain, made information from the Netherlands—whether that was from newspapers, private correspondence, or private conversations in addition to regular diplomatic correspondence—a significant tool of eighteenth-century power politics, particularly in the British Atlantic.

At the same time, these intelligence networks demonstrate that the Dutch Republic, as a major eighteenth-century information entrepôt, transformed into an information battlefield during the Age of Revolution. The outbreak of the American Revolution caused both the British and the Americans to employ their intelligence networks in the Dutch Republic to achieve victory in the conflict. Yet, in contrast to the British, American revolutionaries also successfully unleashed a propaganda campaign to convince the Dutch public of their cause. By infiltrating the liberal and sophisticated Dutch printing press, the American revolutionaries not only succeeded in fostering political support among the Dutch public, but also created a transatlantic intellectual exchange with the Dutch opposition that helped lay the foundations of the Dutch Patriot movement of the 1780s and ultimately the dissolution of the Republic as a whole in 1795.

The “Little London” of Richard Wolters

Dutch primacy in the production and dissemination of information began in the seventeenth century at the height of the Dutch Republic's economic and political power. During the seventeenth century, the rise in global trade of the province of Holland, and the city of Amsterdam in particular, proved foundational to the Dutch Republic's role in information exchanges. Economic information—accompanying the goods and currencies that came from all over the world—flowed freely into the Netherlands through the correspondence of merchants and imperial trading houses, where it was used for capital investments and expansions into heretofore inaccessible markets. Meanwhile, news on political developments flowed copiously into Holland and other provinces in the Dutch Republic and made possible the novel phenomenon of newspapers, which quickly became common and important sources for information on global events. This massive exchange on global economic and political developments was both a product of and a stimulus to the Dutch economy during the seventeenth century, each fuelling the other's rise.Footnote 5

Dutch politicians’ lack of control over their own state intelligence as well as the absence of censorship in the public sphere further enabled Dutch primacy in information exchange during the seventeenth century. As a decentralised state, Dutch provinces, cities, and other localities shared sovereignty with the central government's institutions, such as the States General and, during certain periods, the stadtholderate. This state structure of multiple sovereignties, combined with a culture of relative tolerance towards other religions and ideas, created a society in which one could print on controversial topics that would have been censored elsewhere in Europe.Footnote 6 Additionally, in contrast to other European states, Dutch diplomatic intelligence was easily accessible due to a relatively open government culture. The Republic employed diplomats across the globe who made intelligence from abroad readily accessible, increasing Dutch prominence in global information exchanges.Footnote 7

The wealth of information that flowed through the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century not only proved beneficial to the Dutch but to foreign states as well. The cities of The Hague and Amsterdam became important centres of diplomacy in the seventeenth century. Nearly all of the European powers stationed diplomats in the Dutch Republic—including states and smaller principalities that were relatively marginal powers at this time—who profited from the massive amounts of information that flowed freely through the Netherlands. Some states even used Dutchmen to serve as spies or agents for their own intelligence gathering enterprises. For instance, the English spymaster John Thurloe, whose Commonwealth competed with the Dutch Republic in the mid-seventeenth century, employed the Dutch diplomat Lieuwe van Aitzema to send him intelligence on political developments in the Netherlands during the First and Second Anglo-Dutch Wars.Footnote 8

Dutch primacy in information exchanges during the seventeenth century, combined with Anglo-Dutch geopolitical developments, laid the foundations for the intelligence networks of the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic, upholding the status of the Netherlands as an important centre of news and information. During the 1680s, tensions arose in England regarding King James II, who English Protestants believed had introduced Catholic absolutism on the British Isles. After the birth of a Catholic heir to James in 1687, which threatened to perpetuate Catholicism and absolutism in Britain, the Dutch stadtholder William III saw his chance to live up to his reputation as the defender of the Protestant cause in Europe. At the invitation of Protestant parliamentarians, William invaded the British Isles and overthrew James II. William and his wife Mary—James's Protestant daughter—were subsequently crowned King and Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1688. The Glorious Revolution—as William's coup d’état is called—not only changed the balance of power on the British Isles but also on the European Continent at large. In contrast to the adversarial decades preceding 1688, the Dutch Republic and England formed an unbreakable alliance in the wars against France and its allies during the 1690s based on the rule of William as both stadtholder of the Dutch Republic and king of Great Britain. After the death of the stadtholder-king in 1702, both governments continued to favour a strong Anglo-Dutch alliance, leading to a political and economic integration of the two countries.Footnote 9 For instance, the British were not only able to mimic the Dutch financial and banking industry at home but also employed Dutch financial institutions to fund their wars of imperial expansion during the eighteenth century.Footnote 10

The strong alliance between Great Britain and the Dutch Republic in the eighteenth century also led to a significant expansion of British information gathering in the Dutch Republic, particularly through the Wolters intelligence network, which performed an intelligence collection function similar to other networks during the early modern period.Footnote 11 Richard Wolters, a Dutchman from the city of Rotterdam, became a British agent in the Dutch Republic in 1730, when he was just sixteen years old. The history is sparse for the first thirty years of Wolters’ career, as the archives reveal little information on the beginnings of his intelligence network. In a 1922 article on Wolters's network in the late 1740s, Dutch historian Pieter Geyl claims that Richard became a British agent shortly after the death in 1730 of his father Dirck, who had been an “agent” in Rotterdam for the British crown before his death. Despite the “great many pretenders” for the job opening after his father's death, Richard was chosen to succeed his father.Footnote 12 While most of Geyl's claims are largely unverifiable—he did not cite much evidence in his article—the British National Archives do contain a handful of letters from Dirck Wolters to various high-ranking British officials throughout the early 1720s, indicating the importance of Dirck's job and its connection to intelligence gathering.Footnote 13 Also clear is the start date of Richard's career. At several points during his service Richard Wolters claimed that he started working as a British agent in 1730, substantiating Geyl's claim that Richard essentially succeeded his father.Footnote 14

Operating out of the Dutch city of Rotterdam, the Wolters intelligence network generated a consistent and massive flow of information used for the British state's imperial governance, geopolitics, and foreign policy. The amount of intelligence the Wolters’ network systematically collected in the Dutch Republic was immense, covering over fifty large volumes of correspondence and intelligence reports, about one or two volumes per year. The amount of intelligence is especially large when one considers that many of Wolters’ documents that cover 1730 to 1762 are not archived and quite possibly lost. The documents that have been preserved reveal how the Wolters intelligence network was able to exploit the Dutch Republic's geographic location, its extensive postal services, its mercantile economy, and its government for the benefit of the British. Richard Wolters—like his father before him—had centred his intelligence network around Rotterdam. At first glance, this city seems an illogical place to engage in large-scale intelligence gathering given that Amsterdam was the commercial and The Hague the political centre of the Dutch Republic.

Despite these drawbacks, Rotterdam was an ideal place for Wolters to locate his intelligence network. During the eighteenth century, Rotterdam's economy became increasingly entangled with the economy and information exchange of Great Britain. Merchants from the British Isles, such as those from the Company of Merchant Adventures, had long favoured Rotterdam and the province of Holland in general, due to the relatively small distance of travel. Rotterdam was located in the southwest corner of the Dutch Republic, adjacent to the Meuse River. This location gave the city's merchants easy access to the North Sea and subsequently Great Britain.Footnote 15 Rotterdam's importance to the British gradually increased during the eighteenth century as more British merchants settled in the city as a result of the strong Anglo-Dutch alliance and Britain's expansion in the Atlantic economy. Evidence from later in the eighteenth century indicates that, possibly in part due to its dependence on the British economy, Rotterdam housed several pro-British factions in government and among its merchants.Footnote 16 The extent to which Great Britain and its merchants influenced Rotterdam in the eighteenth century becomes clear when one considers that the city earned itself the nickname “Little London.”Footnote 17

Rotterdam's British character and its geographical proximity to Britain enabled Wolters to gather intelligence. For instance, during the War of the Austrian Succession in the 1740s, Wolters’ letter exchanges reveal extensive use of his contacts in Rotterdam, mainly from the merchant class, for the British war effort. Of particular interest to the British and Wolters at this time was the French city of Dunkirk, which in 1744 and 1745 was supposed to be the assembly point for a combined French and Jacobite invasion of Great Britain. Merchants who traded at Dunkirk informed Wolters of the city's defences and the size and strength of the looming invasion force.Footnote 18 In a similar vein, Wolters's financial records from this period demonstrate that he specifically hired locals to “watch” various suspected Jacobites in 1745.Footnote 19

In addition to its British-dominated mercantile community, Rotterdam also served as an important gateway into Central Europe, creating another significant source of information for Wolters's intelligence network. After the Hanoverian succession in 1714, the elector of Hanover—the ruler of a powerful principality in the Holy Roman Empire—also became king of Great Britain. This personal union between Great Britain and Hanover greatly increased British interest in the political developments in the Holy Roman Empire.Footnote 20 Wolters's network was ideally situated at the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt river delta to send intelligence on these developments. For instance, at the end of the Seven Years’ War, Wolters regarded “the Miseries of the [Seven Years’] War in Germany” as an opportunity to increase the Protestant population of British North America with German immigrants once peace was concluded. Many of the German immigrants to America ended up in Rotterdam before their transatlantic voyage and, as Wolters discovered, were treated horribly by Dutch shippers. The British government, Wolters recommended, should guarantee “Good Provisions, good Room for the People and their Baggage,” including “a small quantity of liquor and tobacco,” a folder with a “short description of the Part of America to which they are to be transported” and “if possible, a Small Map of the Country with it.”Footnote 21 In Wolters’ plan to increase Protestant migration to America, the British government would send so-called Emissaries—“of which there are some” in the Dutch Republic—to the lower Rhine valleys in Germany to spread “an exact account of the [beneficial] Terms that will be granted by the King to the Settlers.” Wolters's network would provide the personnel for the propaganda arm of this operation. Aside from the possible emissaries Wolters knew from the Dutch Republic, Wolters already had a potential leader of the emissaries in mind, who “has for several years past been employed . . . as an Emissary to make Recruits” for the American campaign of the Seven Years’ War.Footnote 22

Rotterdam's proximity to Great Britain also allowed Wolters to create an elaborate communication system outside of the regular postal system to correspond in secret with the British government. Unlike many of his contemporaries working in diplomacy and government, Wolters never used cypher to code sensitive letters, apparently extremely confident that his communications to the British government would not get intercepted; all his quarterly bills to the Northern Department were even conspicuously titled “Disbursements of Richard Wolters for Secret Service.” Several years of receipts from the packet boats that Wolters used for his correspondence reveal that the British government and Wolters consistently used the same ships—most often the Dolphin, the Prince of Orange, and the Prince of Wales—to transport mail packets to each other for a secret line of communication that did not require cypher to mask the letters’ content, significantly improving the efficiency of intelligence gathering. Meanwhile, Rotterdam's proximity to Great Britain greatly aided in the speed with which this information could reach London. Possibly to protect highly sensitive information, the receipts also occasionally mention “His Majesty's Messengers” onboard the ships, who presumably delivered written as well as oral messages to Wolters.Footnote 23

Though Wolters and the British government had created their own communication channel independent from regular postal services, they also actively sought to infiltrate the well-connected Dutch postal network to collect more intelligence. During the 1730s and 1740s, Wolters had already established amicable relations with Dutch postmasters that allowed him to occasionally spy on ongoing correspondence. Wolters elaborates on a scheme between him and a Dutch postmaster in January 1746, who allowed Wolters to “peruse and take the needfull [letters] out” and “allways carefully return them in time” before the letters were sent.Footnote 24

In addition to reading the letters of others, the infiltration of the Dutch post office was also crucial to ensure safe and adequate delivery of mail from Wolters’ so-called correspondents, the network's largest source of intelligence. Throughout his tenure, Wolters employed an extensive network of correspondents spread across Europe, who engaged in intelligence gathering activities in their respective locations. These correspondents evidently also employed their own correspondents in other locations, creating a vast web of intelligence collectors for Wolters who regularly reported their gathered intelligence to him. Subsequently, Wolters analysed the intelligence to separate the wheat from the chaff and, through his secured communication channel with Britain, reported to the Northern Department as well as the Admiralty what he deemed useful intelligence.Footnote 25 Wolters recruited his own correspondents who, according to Wolters, had to be of “an unblemished character, Protestant, . . . active [and] intelligent.”Footnote 26 The number of correspondents differed at various moments. Wolters's network was flexible in size, often larger during wartime, but gradually grew in size during the eighteenth century. Regardless of the size at various times, Wolters always retained at least one main correspondent in Paris and Geneva and, from 1763 onwards, in Madrid as well. The British were well aware of the necessity of secure communications and how the postal network could be compromised. Not only did the British themselves regularly intercept messages for intelligence gathering during the eighteenth century, but the danger of interception also became obvious at various times for Wolters himself.Footnote 27 For instance, in 1764, Wolters suspected an interception of a letter from his Madrid correspondent. In a frantic response, Wolters suggested delivering the intelligence “in the Hands of the Officer of the English Post Office, if there are any; or into those of the Captain of the Packet-Boat in Course for the Mail” and ship the intelligence through England to him.Footnote 28

Wolters’ chances to further infiltrate the Dutch postal network significantly improved after the Orangist Revolution of 1747/48, which fundamentally altered the political balance in the Dutch Republic and subsequently who was in charge of the Republic's postal system. The Orangist Revolution broke out in 1747 as a result of popular discontent with the Dutch ruling elites, who had long governed the Republic through the nepotistic practice called contracten van correspondentie, dividing powerful and lucrative government positions among interconnected ruling families. The death of the childless stadtholder-king William III in 1702 left the position of the stadtholder vacant in five of the seven provinces of the Dutch Republic. Another branch of the Nassau family had provided the stadtholders for the northern two provinces of the Republic—Groningen and Friesland—since the founding of the Dutch Republic in the sixteenth century. These two provinces thus retained a stadtholder after William III's death. Nevertheless, without a stadtholder in the other five provinces, political positions in most of the Dutch Republic were no longer filled as a result of personal patronage of the stadtholder. Instead, various ruling families—called the regenten—gained power in local and provincial governments and distributed political positions among family members and friends.Footnote 29

Between the death of William III in 1702 and the late 1740s, popular resentment against the nepotism of the regenten gradually increased, particularly as natural disasters, a declining economy, and war weighed heavily on the Dutch Republic during the 1730s and 1740s. When a French army threatened to invade and overrun the Dutch Republic during the War of the Austrian Succession in 1747, violence started in the northern provinces against the so-called pachters, private tax collectors who exploited their position of power to skim large profits from tax collections. The protests soon spread throughout the Dutch Republic against all forms of nepotism. The rioters demanded the reinstatement of the stadtholder who, they believed, could crush the nepotism that caused the Republic's decline. After much popular clamour, William IV, the stadtholder of Groningen and Friesland, was declared the stadtholder of all the seven provinces of the Republic in May 1747. Yet true reforms still needed to be implemented. Various movements rose in cities across the Dutch Republic—the Amsterdam Doelistenbeweging (Doelisten movement) as the most prominent one—that sought to leverage the stadtholder's newfound power to crush the nepotism of the regenten. Footnote 30

The Orangist reformers envisioned a broad overhaul of the selection process for public officials, including the postmaster positions. Like many other government posts in the Dutch Republic, the appointment system for the postmasters was nepotistic to its core. Burgomasters shamelessly appointed their newborn sons and toddler grandsons as official postmasters, granting their family members thousands of guilders annual income without doing any of the work associated with the position. The post offices in the city of Amsterdam were particularly important to the regenten and also especially nepotistic. The Amsterdam government had used the city's position as the primary commercial centre in the Dutch Republic to monopolise the postal services destined for various places around the world. This strategy ensured Amsterdam's primacy in information exchanges in the Dutch Republic, and a large guaranteed income for the family members of the regenten. Footnote 31 The reformers argued that Orangist control over these post office appointments would solve the problem of nepotism while simultaneously breaking the monopoly on information that the regenten held.Footnote 32

The Orangist revolution and the proposed postal reforms particularly animated Wolters in 1747 and 1748 and he actively supported the Orangist cause behind the scenes. The post offices played a crucial role in the Dutch information exchanges, which meant that the person who appointed the postmasters would have substantial influence on the workings of Wolters's network. The post between England and the Dutch Republic was also managed in a post office in Amsterdam, making Wolters especially concerned over the political developments there.Footnote 33 As the Orangist revolutionaries were demanding control over the Amsterdam post offices in 1747 and 1748 and the Amsterdam government refused, Wolters incessantly reported to various British officials on the progress the Orangists were making on postal reform, largely agreeing with the Orangist demands.Footnote 34 Wolters even personally encouraged the stadtholder and Laurens van der Meer—the stadtholder's delegate to Amsterdam—to pressure the Orangists to continue their demands for postal reform.Footnote 35

In the end, the solution to the question of the postmaster appointments greatly bolstered the power of the stadtholder. To solve the controversy, stadtholder William proposed that—instead of the regenten—he would control the appointments to the post offices in the future, mimicking his power grab in various other powerful institutions in the Dutch Republic, such as the West and East India Companies.Footnote 36 The Orangist reformers—much enamoured of the stadtholder—accepted his proposal and moved on to other reforms. They apparently failed to recognise how this new appointment system would perpetuate the nepotism they had sought to destroy by shifting the source of nepotism from the regenten to the stadtholder.

The change in how postmasters were appointed proved extremely beneficial to Wolters's intelligence network as well. The British government acted friendly towards the stadtholder's new regime—in part because the stadtholders were related to the British monarchs—and pursued a strong alliance with the Dutch Republic during the 1750s and 1760s. Presumably by leveraging British clout in the stadtholder's government in this period, Wolters gradually infiltrated the post offices in both Hellevoetsluis and Den Briel. Wolters's infiltration of these post offices gave him control over a significant portion of the information that flowed from the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt river delta as well as from Great Britain to northern Europe. During the 1760s, George Shelvocke—Great Britain's secretary of the post office—recommended to Wolters that he should hire a certain Mr. Gravius as his deputy to handle all the correspondence coming from Wolters's private communication channel with the British government. Shelvocke recommended Gravius because he was already a clerk at the post office in the Dutch town of Den Briel. Gravius was, therefore, able to gather intelligence from letters and people going in and out of the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt river delta as well as handle Wolters’ communications with the British government at the same time.Footnote 37

Control over the post offices in Den Briel and Hellevoetsluis continued to be of significant value to Wolters during the 1760s and he spent much effort in retaining his assets there as the years progressed. Gravius died at some point in the 1760s and a certain Peter Leening succeeded him, who Wolters subsequently hired as his deputy since it was convenient to continue “to have both offices combined” in one person. In 1769, Wolters recommended to the Earl of Sandwich—the secretary of state of the Northern Department—that his secretary Charles Hake should work under Peter Leening. Wolters explained that Leening—“though in the best of his days”—was a “Martyr of the Gout” and that Leening's successor, Mr. Swalmius, had “a total ignorance of the English language.” Moreover, Wolters reasoned that Swalmius's “Friends Desire to push him in the Magistracy, will make him less governable, and out of the reach of Punishment in Case of Misbehaviour.” Leening's looming death and Swalmius's succession could undo Wolters’ control over the post office in Den Briel. To remedy this problem, Wolters personally requested William V—the new stadtholder of the Dutch Republic—to intervene and replace Swalmius with Hake at the Den Briel post office. Because of “the Multiplicity of Sollicitants for the few Places that become vacant in so Small place as the Briell,” Wolters also requested Great Britain's Northern Department to finance Hake separately to be the successor of Leening, since control over the Den Briel post office had proven so fruitful, “particularly in [the last two] successive Wars and in the last Rebellion.”Footnote 38

“America's Friends Do Not Sleep”

Though Wolters’ intelligence network successfully employed the Dutch Republic's political system, postal service, and geographic location in service of a foreign government in the eighteenth century, his network was not the only one to do so. Starting in the 1760s, the Dutch Republic became increasingly entangled in the disputes between Great Britain and its North American colonies. During the 1760s and 1770s, Dutch merchants smuggled large amounts of consumer goods and (eventually) war materiel to the American colonies. These smuggling activities created discord between Great Britain and the Dutch Republic and simultaneously revitalised the Dutch political opposition, which increasingly looked to the American revolutionaries for ideological guidance. As the American Revolution unfolded and the Americans sought diplomatic support in Europe during the 1770s, they, like the British, recognised the benefits of the Dutch Republic as the eighteenth-century information entrepôt and recruited American sympathisers in the Dutch Republic for intelligence purposes. Though not nearly as voluminous, independent, or as enduring as Wolters’ intelligence network, the American intelligence network in the Dutch Republic was tightly intertwined with American diplomatic efforts in Europe and proved successful in collecting intelligence for their newly established government. Additionally, the American intelligence network in the Dutch Republic proved even more successful in shaping Dutch public opinion by waging an information war for the American revolutionary cause. American success in the information wars in the Dutch Republic between 1775 and 1780 infused Dutch political discourse with revolutionary ideas that helped create the Dutch Patriot movement in the 1780s, which ultimately caused the downfall of the Dutch Republic altogether in 1795.

Like Wolters’ intelligence network, the American revolutionaries employed the Dutch Republic's political system, geographic location, and postal services for intelligence gathering, based on long-standing entanglements in the Dutch economy and politics as well as the Republic's status as Europe's information entrepôt. Starting in the early 1760s, American colonists increasingly used Dutch merchants and ports to support their protest against Great Britain and undermine British attempts to control their transatlantic trade. Especially after the passing of the Townshend Acts of 1767 and 1768—which implemented taxes and new enforcement measures on the trade in consumer goods to Britain's North American colonies—American colonists used Dutch merchant networks to smuggle consumer goods to America and subsequently undermined the British government's attempts to pay back the debts it had incurred during the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763). American colonists particularly used the Dutch Caribbean island of St. Eustatius to smuggle goods to America, including tea and firearms, significantly contributing to the Tea Act crisis in 1773 and the eventual outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775.Footnote 39

After the outbreak of the war, the American revolutionaries established an intelligence network of various pro-American figures in the Netherlands as part of a broader diplomatic effort to shore up support for their cause in Europe. The most prominent and active among these figures was Charles Guillaume-Frédéric Dumas, who grew infatuated with America during the 1760s and 1770s. Dumas, born in Germany, had moved first to Switzerland and then to the Dutch Republic in the 1750s. Probably in 1766, Dumas met the American printer, scientist, and future revolutionary Benjamin Franklin on the latter's travels through Europe. A correspondence started that mostly pertained to their shared love of science, the arts, and literature.Footnote 40 The letters from Dumas in the spring and summer of 1775 demonstrate the extent to which Dumas had become an American sympathiser. For instance, Dumas sent Franklin various copies of Emmerich de Vattel's The Law of Nations, the new edition of which Dumas was the editor and had written a foreword that spoke favourably of the American colonies and their continued protests against Great Britain.Footnote 41 Though correspondence between Franklin and Dumas was initially of an intellectual nature, it became more political in 1775 after the American revolutionary war began.

In part due to his dedication to the American cause, the Continental Congress employed Dumas to become their agent in the Dutch Republic in late 1775. Acting in secrecy (at least in theory) the Congress tasked Dumas to convince foreign diplomats in the Netherlands of America's economic potential and that American forces could defeat Great Britain on the battlefield. Aware of the many Dutch merchants already engaged in illicit trade to America, Franklin asked Dumas on behalf of Congress to entice more merchants to “make great profit [in America]; such is the demand in every colony, and such generous prices are and will be given.” Strikingly, Franklin explained to Dumas that America was “in great want of good engineers” and asked if Dumas could “engage and send us two able ones, in time for the next campaign, one acquainted with field service, sieges, &c. and the other with fortifying of sea-ports.” Finally, Dumas was paid a lump sum of a hundred pounds sterling for his services, putting him officially on the payroll of the Continental Congress.Footnote 42

As an American agent, Dumas engaged in intelligence gathering activities that were in many ways very similar to Wolters. Like Wolters, Dumas had a—presumably smaller—network of correspondents, particularly in Germany, whose letters he regularly forwarded to the Congress and eventually to Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and John Adams, the three American commissioners in Paris who sought to make an alliance with France in 1776 and 1777. Dumas regularly interacted with various members of the Dutch government, although he possessed nowhere near as much influence as Wolters did, particularly at the beginning of his tenure. Many members of the Dutch government were still relatively pro-British and few risked being associated with Dumas, the American “rebel” agent. Doing so could potentially upset the Dutch Republic's lucrative and politically convenient neutrality in the conflict. In 1778, Dumas described how people used to laugh at him for his allegiance to the Americans, indicating his position as somewhat of an outsider in 1776 and 1777.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, Dumas was able to provide reliable intelligence on domestic Dutch political developments, which became more important as tensions between the Dutch Republic and Great Britain—and thus the possibility of Dutch recognition of American independence—increased between 1777 and 1780.

Dumas had also infiltrated the Dutch postal service, although not in the sophisticated way that Wolters had after the Orangist Revolution. Letters between Dumas and the Americans from 1777 onwards indicate that Dumas had established amicable relations with an unnamed “Postman” with whom he exchanged information on various political developments in Europe and America and through whom he occasionally sent letters as well. Belief in the American cause apparently motivated Dumas’ postman; to celebrate their cooperation Dumas and the postman toasted “to the success of the American arms,” even though the postman was ill at the time.Footnote 44

Unlike Wolters, Dumas did not have his own fleet of packet boats that protected the contents of his correspondence and therefore relied on more convoluted methods to communicate securely with his American superiors. The distance between North America and the Netherlands greatly increased the chance of interception at sea and even the intelligence Dumas sent to the American commissioners in Paris could be easily intercepted along the way. To secure his communications with the Americans, Dumas devised a book cypher based on passages from the edition of Emmerich de Vattel's The Law of Nations that he had edited and sent to the Continental Congress. The American revolutionaries subsequently used Dumas's cypher to code some of their communications as well.Footnote 45 In addition to the book cypher, the Americans also instructed Dumas that, if he did not have “a direct safe opportunity,” he should send his return letters to the Congress “by way of St. Eustatia, to the care of Messrs. Robert and Cornelius Stevenson, merchants there, who will forward your dispatches” to America.Footnote 46 St. Eustatius—an island in the Caribbean under control of the Dutch West India Company (Westindische Compagnie or WIC)—had been a smuggling port for the Americans for over a decade and from 1775 onwards also served as an intelligence channel between Europe and America.Footnote 47

In contrast to Wolters, Dumas integrated into the American diplomatic scene and effectively became a diplomatic aide to John Adams when the latter arrived in the Netherlands to represent the United States in 1780, symbolising the intertwining of American diplomacy and its intelligence network. Dumas received Adams on his arrival to the Dutch Republic, helped him in his diplomatic negotiations, and even taught the teenaged John Quincy—Adams’ oldest son and a future president of the United States—some basic cyphering skills.Footnote 48

In addition to Dumas, the American revolutionaries also employed a number of other agents in the Dutch Republic for their cause in the late 1770s. For instance, a British clergyman in Rotterdam named Benjamin Sowden volunteered to pass on intelligence to the American commissioners in Paris in 1777. Though he was not personally familiar with Franklin, as Dumas had been, Sowden initiated a correspondence with Franklin based on their mutual acquaintances Richard Price and William Gordon, the latter of whom was a pastor from Boston who Sowden had befriended. Because his letters to Gordon apparently failed to reach America, Sowden asked if Franklin could forward his letters and offered the same service to Franklin if he ever needed to send a message to any of his “old Friends, by a very secret and safe mode of conveyance.”Footnote 49 Eager to expand his network of pro-American sympathisers in the Dutch Republic, Franklin agreed with Sowden's forwarding request and a correspondence started in 1777 in which Sowden relayed intelligence to Franklin. Sowden, like Dumas, sent Dutch publications to Franklin and also established an amicable relationship with a certain “Post Master” who fed him information.Footnote 50

At the same time, Sowden reported on conversations he had with people in the British community of Rotterdam, which, as a reverend of the English church, he was quite familiar with. For instance, one conversation with “an old English acquaintance, who is a Man of Character, a zealous advocate for the British Ministry, intimate with all the Dutch Ministers of State, nor less so with [British ambassador to the Dutch Republic] Sir Joseph Yorke,” revealed to Sowden that a certain Mr. Wentworth had taken possession of one of Franklin's memorials that sought to convince the French government of supporting the United States in their war with Great Britain. Sowden warned that Franklin should know Wentworth's “real political tenets” and was “hereby put upon Your guard against [Wentworth's] Wiles for the future.”Footnote 51 The Mr. Wentworth Snowden referred to was Paul Wentworth—a long-time confidant of Franklin's—who was employed by the British government to spy on the American commissioners in Paris. Though the Americans grew increasingly suspicious of Wentworth during 1777, Sowden probably helped expose Wentworth's nefarious activities.Footnote 52 Ironically, the British government quickly uncovered Sowden's own intelligence gathering activities for the Americans after they had intercepted a ship from Boston with Sowden's letters onboard, presumably the correspondence that Sowden had asked Franklin to forward.Footnote 53

Not even nine months after the British discovered Sowden was working for the Americans, Sowden's daughter Hannah wrote to Franklin informing him of her father's passing, describing him as a “man of Letters, and a friend to both civil and religeous [sic] liberty” like Franklin.Footnote 54 We will never know how much intelligence he could have collected, but Sowden's zeal and efficacy, as well as his network of British merchants in Rotterdam, would probably have been of considerable value to the American revolutionaries in the next few years if he had not died in 1778.

Though the American revolutionaries profited greatly from receiving intelligence from the Dutch Republic in the late 1770s and early 1780s, they were even more successful in using their intelligence networks to influence Dutch public opinion, which helped shape Dutch political and cultural discourse of the 1780s. In addition to its value as an intelligence hub, the American revolutionaries considered the Dutch Republic a potentially significant strategic asset in their war against Great Britain in the late 1770s. The Dutch financial sector—rivalled only by London's—could potentially provide the United States with credit for its cash-strapped government. In addition, the Americans were convinced of their country's economic potential and reasoned that the Dutch—who had been so eager to smuggle to America during the 1760s and early 1770s despite Britain's objections—could be seduced with America's economic opportunities. At the same time, the Americans believed that the Protestant, republican Netherlands could be persuaded to recognise American independence, particularly after learning in the mid-1770s that the Dutch Republic harboured many pro-American sympathisers.Footnote 55

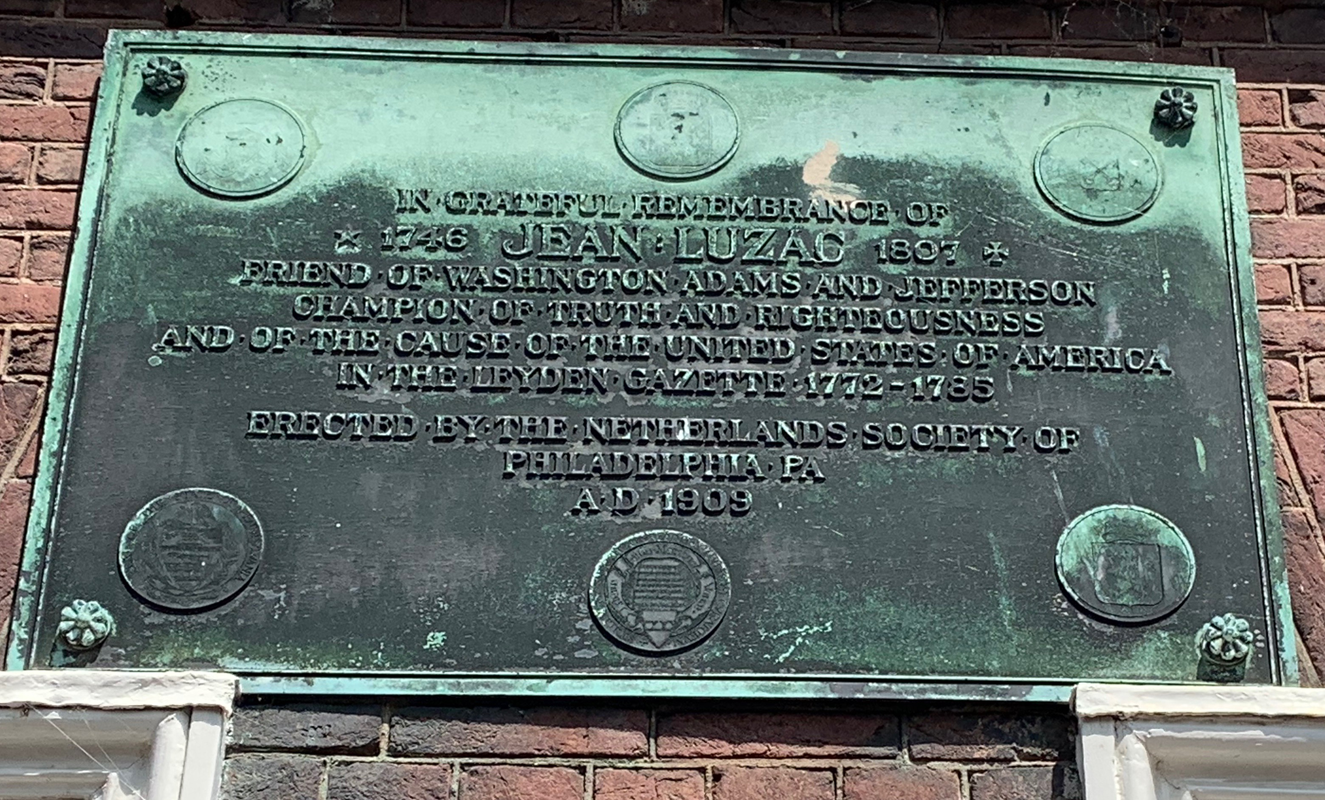

In order to win over the Dutch Republic as a strategic asset in their war for independence, the American revolutionaries deployed a significant propaganda campaign, a method they had used successfully to mobilise public support for their revolution in America.Footnote 56 American agents in the Dutch Republic were deeply connected to the Dutch press and exploited these connections to shape Dutch public opinion on the American Revolution at the direction of Franklin and the Congress. Dumas, for instance, had been in the business of translating and printing since at least the early 1760s. As a result, he had developed amicable relationships with various printers and editors, in particular with the editors of the Nouvelles Extraordinaires de Divers Endroits (Extraordinary news from various places) or Gazette de Leyde (Leiden Gazette), published in Leiden, and the Courier du Bas-Rhin (Courier of the Lower Rhine), published in the Prussian exclave of Kleve just across the Dutch border. These prominent newspapers were published in French and read all over the Dutch Republic and Europe, giving Dumas's propaganda efforts a European-wide reach.Footnote 57 The information that Dumas had published often came from the American commissioners in Paris or the Congress, relaying a pro-American narrative on the revolution in the Dutch Republic and Europe more broadly. In 1777, for instance, Dumas explained how he had “informed two of our most esteemed Dutch Gazettiers” of an extract that Franklin had sent him that painted a positive picture of American treatment of prisoners of war, despite the supposed cruelty of the enemy troops. Dumas's cooperation with the newspaper editors went so far that they even proactively made suggestions to improve American propaganda in their newspapers. In 1777, the famous editor of Gazette de Leyde Jean Luzac proposed to contrast narratives of American humanity with “the account of the cruelties that the American prisoners have experienced,” which Dumas planned to have translated to German and published in Germany to undermine Britain's reputation there.Footnote 58 In his efforts as an American propagandist, Luzac became such a loyal ally to the Americans during their revolution that the Netherlands Society of Philadelphia would honour him in 1909 with a plaque in Leiden, describing him as a “friend of Washington, Adams[,] and Jefferson [as well as] a champion of truth.”

Fig. 1. Plaque in Leiden honouring Jean Luzac by the Netherlands Society of Philadelphia, 1909.

Sowden likewise exploited his connections with Dutch printers, particularly with Reinier Arrenberg, a “Printer, Bookseller, and Courantier” in Rotterdam. Like Dumas, Sowden received copies of American newspapers, which he forwarded to Arrenberg, who published it in his Rotterdamsche Courant (Rotterdam Courant).Footnote 59 According to Sowden, the pieces from the American newspapers were “copied in most of the other Courants of this Country,” including Luzac's Gazette de Leyde. Footnote 60 Arrenberg himself also started a separate correspondence with Franklin, sharing a love for science and membership in Rotterdam's Batavian Society for Experimental Philosophy. In his letters, Arrenberg begged Franklin to send him news from America, promising to keep their correspondence a secret. “As Gazzetier of this City,” Arrenberg complained, “I must content myself only with the News I receive from England,” which favoured the British narrative. Because there were so many friends of America in the Dutch Republic, Arrenberg reasoned that with Franklin's help he could “satisfy the desire of those who want to have real news from the American side.”Footnote 61 Though presumably at least partially motivated by the economic opportunity to boost the sales of his newspaper, Arrenberg's personal affiliations also betrayed his ideological sympathies for the American revolutionaries, motivating him to work with Franklin. In addition to Sowden, Arrenberg counted among his friends Adrianus Dubbeldemuts, a merchant bookkeeper from Rotterdam who acted as a messenger for the correspondence between Sowden and Franklin, falsified documents of Dutch merchants smuggling to America, and played host to John Adams when he came to the Netherlands to negotiate with the Dutch government in 1780.Footnote 62

The Americans also leveraged the pro-American sympathies of the future Dutch revolutionary Reference van der Capellen tot den Pol and de BeaufortJoan Derk van der Capellen tot den Pol to spread propaganda in favour of the American cause. Though originally born in Tiel in the province of Gelderland, van der Capellen bought his way into Dutch politics in 1772 when he acquired an estate in the province of Overijssel, becoming a member of the provincial States there. His studies and observations on Dutch politics during the 1750s and 1760s had convinced van der Capellen that the stadtholder and his Orangist regenten had thoroughly corrupted the Republic's political system and that reform was needed to restore the Republic's former glory. In the early 1770s, van der Capellen started to sympathise with the American colonial protests and regarded the Americans as a people in a similar struggle for liberty as the Dutch. Van der Capellen was also zealously anti-British, largely because of the strong connections between the British government and the Orangist elites he considered corrupt.Footnote 63

In 1775, van der Capellen asserted his pro-American sympathies publicly when he started a small pamphlet war against the British government's attempts to use the Scots Brigade against the Americans after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775. The Scots Brigade were army companies technically loyal to Great Britain which the English government had lent to the Dutch Republic in the sixteenth century for the defence of the Republic's borders against the Spanish. The Brigade had subsequently defended the Dutch Republic's borders for nearly two centuries, for which the States General had consistently footed the bill. To the Dutch mind, the Scots Brigade was part of Dutch border defences under Dutch command.Footnote 64 After Britain requested that the Dutch government place the Scots Brigade again under British command to be used against “His Majesty's Rebel subjects” in America, van der Capellen held an oration in the States of Overijssel, the text of which he had subsequently leaked to the press to create a public uproar against Britain's plans. In his speech, van der Capellen railed against the British and Dutch governments, recounting a long history of British attempts to abuse the Anglo-Dutch alliance for only their benefit. At the same time, van der Capellen objected to the use of the Scots Brigade against “what some call a Rebellion of American colonists. . . . The fire that burns in America,” van der Capellen warned, “may set the whole of Europe, that is full of combustibles, ablaze.”Footnote 65

Van der Capellen's widely publicised speech unleashed a small pamphlet war and subsequently succeeded in blocking Britain's plans with the Scots Brigade, making his pro-American sympathies known in American revolutionary circles.Footnote 66 In 1777, a Dutch merchant living in America called Gosuinus Erkelens wrote to van der Capellen from Philadelphia and expressed thanks on behalf of the Congress “and thousands [of others] in a radius of 1500 miles” for van der Capellen's help with the Scots Brigade and the “suppression of unlawful tyrants.” In order to “further influence the opening of a connection and understanding” (connectie en verstandhouding) between the United States and the Dutch Republic, Erkelens—a self-proclaimed inhabitant of New England and associate of governor Jonathan Trumbull of Connecticut—asked van der Capellen on behalf of the Congress to translate and publish various documents. Erkelens’ mail packet included letters of Jonathan Trumbull and William Livingston, the governor of New Jersey, from 1775 that provided an intellectual defence of the American revolutionary cause.Footnote 67 Van der Capellen demonstrated his zeal for American liberty by dutifully publishing the letters, which were reprinted in the following years.Footnote 68 He also started a correspondence with Trumbull himself, whose address Erkelens had given in his letter.Footnote 69

In addition to publishing the Trumbull letters, van der Capellen offered his services to Franklin and published other pro-American pieces in the Dutch press. For instance, in 1776, van der Capellen translated the famous pamphlet of the American revolutionary Richard Price, entitled Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, the Principles of Government, and the Justice and Policy of the War with America. Van der Capellen linked Price's thoughts on the American conflict directly to the political problems in the Dutch Republic. Price's pamphlet, van der Capellen argued, should serve as a larger reflection on the principles of the Dutch government and remind the Dutch people of the supposed corruption of the stadtholderate and its ties to tyrannical Britain.Footnote 70

The American information wars of the late 1770s profoundly shaped Dutch public opinion, largely in favour of the American revolutionaries. Pro-American sympathies had been latently present among opposition members in the Dutch Republic, many of whom imagined the American Revolution to be similar to the Dutch Revolt of the late sixteenth century. Moreover, much Anglophobia existed in the merchant communities of the Dutch Republic given Britain's attempts to prevent their lucrative trade with America. The American information wars aroused, replicated, and helped spread these dormant sympathies. In addition to publications from characters such as Dumas, Sowden, Arrenberg, and van der Capellen, many others in the Dutch Republic wrote sympathetically on the American Revolution on their own accord.Footnote 71 As Dumas put in 1780, “America's friends [in the Dutch Republic] do not sleep.”Footnote 72 The increasingly pro-American sympathies among the Dutch public in the late 1770s were especially evident when John Paul Jones, the famous American naval commander, sought refuge in the Dutch Republic in 1779 after defeating a British naval squadron off the coast of Scotland. When Jones arrived in Amsterdam throngs of people came out to see him, crowds in theatres held standing ovations for him, and songs were composed to praise his skills on the battlefield.Footnote 73

The Dutch Republic's increasing pro-American stance led to the outbreak of the so-called Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in late 1780, laying the groundwork for the Patriot Revolution. The British Royal Navy proved superior to the Dutch Republic's navy, which caused a major public backlash against the stadtholder. The public largely faulted the stadtholder and his government for neglecting the navy's upkeep and regarded the stadtholderate incapable of governing the Republic. In his seminal pamphlet Aan het Volk van Nederland (To the people of the Netherlands) from 1781, van der Capellen blamed the stadtholder and his government for being weak and unresponsive in the Republic's war with Britain. Inspired by American revolutionary thought and the American example of rebelling for liberty, van der Capellen called for the election of people's representatives to hold the stadtholder accountable as well as for the creation of local militia units that would defend the local rights and privileges of citizens against the stadtholder's tyrannical impulses.Footnote 74 In response to van der Capellen's pamphlet, so-called Patriots ousted incumbent Orangist vroedschappen (local governments) all over the Dutch Republic and organised themselves in excercitiegenootschappen (militia units) in the subsequent years to protect their “rights and privileges” against what they believed to be the corrupted power of the stadtholder.Footnote 75

The outbreak of war between Great Britain and the Dutch Republic in 1780 proved consequential for the American intelligence network in the Dutch Republic as well. Though they did not constitute a formal alliance, the war placed the Dutch Republic firmly on the side of the United States, France, and Spain. The Dutch States General recognised American independence and Dutch bankers extended a loan to the United States government in 1782. It also became increasingly clear the extent to which the Dutch public had sided with the American cause. The war—and subsequently Dutch recognition of American independence—removed the American necessity of continuing the information war and convincing the Dutch public of the righteousness of their cause. Dumas and John Adams, the latter of whom the Congress had appointed United States Minister to the Netherlands, continued to send intelligence from the Dutch Republic between 1781 and 1783, but they offered barely any encouragement to influence newspapers or produce pro-American pamphlets.

Wolters's network was highly dependent on the peaceful relations between Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The British government had employed Wolters's network in their conflict with the North American colonies in the 1760s—particularly to track down American-Dutch smugglers—but became less involved as the conflict turned into a rebellion during the 1770s.Footnote 76 Richard Wolters died after an epileptic fit in 1771 and was succeeded by his wife, Marguerite. She continued Richard's work with the help of his trusted secretary Charles Hake and even expanded the network of correspondents to Central Europe. But the sources also suggest that Marguerite largely kept up the regular reporting without actively gathering intelligence from the merchant community. Hake seems to have been assigned to take over this role, but he was significantly less successful in getting useful intelligence than Richard had been. Presumably, Marguerite's gender prevented her from engaging the merchants on an equal social footing, while Hake was perhaps not trusted enough among Richard's former contacts. In any case, he proved far less capable than Richard.

The outbreak of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in 1780 crippled the network that Richard Wolters had painstakingly built over the last five decades. The war destroyed the network's separate and secure communication infrastructure with Great Britain, since ships were no longer able to travel freely between the two countries. Moreover, the war created a virulent anti-British environment in the Dutch Republic, particularly among merchants hit the hardest by the war with Britain. This atmosphere made it impossible for Marguerite and Hake to continue to gather intelligence for the British in the Netherlands. The Treaty of Paris of 1784 eventually settled a peace between the Dutch Republic and Great Britain—as well as peace between Great Britain and the United States—but political instability of the 1780s prevented the Wolters network from resuming its regular intelligence activities in the Dutch Republic. Marguerite and Hake found it difficult to find new correspondents, apparently having lost many during the war. The organisation moved briefly to Oostende in the Habsburg Netherlands, which, like Rotterdam, was located within the vicinity of Great Britain and next to the North Sea. They nevertheless proved unsuccessful in creating a reliable correspondent network, prompting the British government to disband the organisation completely in 1785.Footnote 77

Though a Prussian invasion would crush the American-inspired Patriot movement in 1787, the Patriots had substantially weakened the stadtholder's legitimacy in the Dutch Republic. The stadtholder and his allies, the British chief among them, viewed the defeat of the Patriots as a glorious revolution, akin to the Orangist Revolution of 1747 that had made the stadtholderate such a powerful institution. Yet the Prussian invasion that the stadtholder and his Prussian wife had invited mostly demonstrated the weakness of the stadtholderate and delayed the political reforms that the Dutch Republic desperately needed. As Alfred Cobban has detailed, the British and French governments vied for control over the Dutch Republic in the late 1780s and early 1790s, with a weak stadtholderate caught in between.Footnote 78 After eight years of desperately clinging on to power, it did not take much effort to depose the stadtholder's government when the French revolutionary forces invaded in 1795.

Conclusion

Situated between the Golden Age of the seventeenth century and the creation of the modern Dutch nation-state in the nineteenth century, scholars have long considered the eighteenth century a less significant period in the history of the Netherlands. Yet the Wolters and American intelligence networks demonstrate the crucial role the Dutch Republic played in intelligence gathering and dissemination in the eighteenth-century Atlantic. Massive amounts of intelligence flowed freely from the Dutch Republic to Great Britain, America, and likely many other places around the globe that helped shape imperial governance and geopolitics during the eighteenth century.

At the same time, these Anglo-American intelligence networks also deeply affected the Dutch Republic, helping to lay the foundation for the Patriot Revolution of the 1780s. The propaganda campaign of the American revolutionaries in the Dutch Republic between 1775 and 1780 proved crucial in shaping the rapidly changing Dutch political and cultural discourse of the coming decades. As Great Britain's ambassador to the Dutch Republic, Sir Joseph Yorke, put it, no intrigue was “spared to animate the people” of the Netherlands during the American Revolution.Footnote 79

Unquestionably, the Dutch Republic experienced a period of geopolitical, political, and economic decline during the eighteenth century. Yet the remaining dynamism of the Republic's economy, its nepotistic institutions, its highly developed printing press, and its integration into the British Atlantic created an intelligence hub for world empires and rising states alike, ultimately helping to destroy the Republic and fundamentally change Dutch history in the process.

Bio and Acknowledgements

Matthijs Tieleman is a PhD candidate in History at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He would like to express his gratitude to Itinerario's editorial staff and editor-in-chief as well as the anonymous reviewers for helping improve this article. He also especially wants to thank Margaret Jacob and Carla Pestana for supporting his research and reading this article in its various stages of development. Without their support and feedback, this article would not have been possible.