Corruption, as the abuse of public power for private gain, has attracted increasing attention from both political scientists and economists (e.g., Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Treisman, Reference Treisman2007; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2011; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016; Uslaner and Rothstein, Reference Uslaner and Rothstein2016; Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017; Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charron2018). In explaining economic prosperity and social development, a huge body of the literature emphasizes the importance of the quality of government institutions and state capacities (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013). In light of this institutional approach, disregard for the rule of law and failure to control corruption are fundamentally detrimental to socioeconomic development. Moreover, given the natural link between democratic accountability and curbing corruption, the magnitude of corruption is commonly considered a critical indicator of the performance of democracy. Higher levels of corruption could fundamentally undermine citizens' support for democratic political institutions in both mature and newly established democracies (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Seligson, Reference Seligson2002; Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Norris, Reference Norris2011; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016).

However, this institutional approach falls short in explaining the impacts of campaign-style anti-corruption in authoritarian regimes. Lack of accountable institutions like competitive elections and free media, authoritarian governments often rely on campaign-style enforcement to curtail corruption (Gillespie and Okruhlik, Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1991; Holmes, Reference Holmes1993; Manion, Reference Manion2004; Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2005; Sun and Yuan, Reference Sun and Yuan2017; Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017). For instance, in the Soviet Union, Rwanda, and South Korea, large-scale anti-corruption campaigns were launched repeatedly. Yet, scholars tend to be divided on the political motivations behind these anti-corruption campaigns as well as their actual impacts on popular support of authoritarian regimes. Some scholars argue that intra-elite power competition is a major force driving repeated anti-corruption campaigns, and thus such campaigns may do little to bolster regime legitimacy (e.g., Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017). Other scholars challenge the argument that corruption is inherently a political evil. Huntington (Reference Huntington1968), for example, argues that ‘corruption provides immediate, specific, and concrete benefits to groups which might otherwise be thoroughly alienated from society’ (p. 64). In other words, by binding the society together, corruption seems to be a necessary evil and can help enhance regime legitimacy in authoritarian settings (Huntington, Reference Huntington1968; see also Seligson, Reference Seligson2002).

Unfortunately, collecting data on corruption and anti-corruption campaigns is notoriously difficult in authoritarian countries. This difficulty often constrains our understanding of the relationship between corruption and regime legitimacy in authoritarian settings.Footnote 1 This study intends to fill the gap by presenting and analyzing data on China's ongoing anticorruption campaign led by China's current leader, Xi Jinping. It should be noted that ever since the beginning of the post-Mao economic reform, China's leaders have launched numerous campaigns to crackdown the rampant corruption. But Xi's campaign starting from late 2012 differs notably from previous ones because it targets senior officials (i.e., ‘tigers’) and introduces institutional changes.

In this study, by integrating official anti-corruption data with data from nationwide surveys conducted in 36 major cities in China in 2011, 2012, and 2015, we explore the potentially different impacts of anti-corruption campaigns on popular political support for the current Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime. Our analysis shows that the overall popular support has declined steadily overtime, despite the positive effects of Xi's anti-corruption campaign. Specifically, ordinary Chinese did react positively to Xi's targeting on both senior officials (‘tigers’) and grassroots cadres (‘flies’). Xi's campaign, particularly his crackdown on ‘tigers,’ increased people's trust in the central government. However, the campaign fails to restore the declining central and local government legitimacy. Our findings thus cast doubt on the very effectiveness and sustainability of Xi's campaign-style anticorruption. Furthermore, our analyses reveal that the legitimacy loss can be attributed to some long-term factors like rising education levels, a thriving private economic sector, an increasingly pluralized society, and the unsustainability of performance legitimacy.

By integrating longitudinal surveys with anti-corruption campaigns throughout Hu and Xi eras, our study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, most existing studies on relationship between corruption and popular supports rely on one-time and snapshot survey data, which make it difficult, if not impossible, to detect trends of the legitimacy of the CCP regime overtime, not to mention how anti-corruption campaigns could shape the public opinion toward the regime. This problem is particularly acute when we try to weigh the actual effects of the campaigns against some other long-term legitimacy correlates like the booming private economy and rising education levels (e.g., Chen and Lu, Reference Chen and Lu2011). Second, our study sheds light on the limits of campaign-style anti-corruption in restoring regime legitimacy in China (also see Sun and Yuan, Reference Sun and Yuan2017). While we do find positive effects of anti-corruption campaigns on people's trust in the central and local, such positive effects are dwarfed by some other long-term effects associated with a more modernized, better educated, and pluralized society.

In the following section, we will begin with our discussion on the theoretical approaches on the relationship between corruption and legitimacy. We then explain why China's recent anti-corruption campaign can serve as a critical case. We will operationalize and gage popular political support and anti-corruption efforts in the Chinese setting, examine the empirical correlation between the two, and finally conclude with a discussion on the findings and their implications.

1. Theoretical background: corruption and regime legitimacy

Corruption has been one of the most pervasive and persistent political phenomena. From the perspective of an institutional approach, corruption undermines formal political institutions by channeling public resources illicitly to private ends. Specifically, it is argued that rampant corruption could cause the public's disillusion in democracy via both economic and political mechanisms (e.g., Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Treisman, Reference Treisman2007; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016; Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charronforthcoming). Economically speaking, some scholars have long warned the detrimental economic impacts of corruption. They believe that rampant corrupt could markedly increase transaction costs and thus reduce investment incentives and economic growth. Such negative effects of corruption have been documented in myriad of empirical studies (Treisman, Reference Treisman2007; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). Politically speaking, corruption challenges key principles of democracy like accountability, equality, and openness (Dahl, 1971; Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Norris, Reference Norris2011). When corruption is rampant, as Anderson and Tverdova (Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003) noted, ‘democracy's tenets of procedural and distributive fairness become a myth; this, in turn, is likely to diminish the legitimacy of democratic political institutions’ (p. 93). In sum, for most institutional scholars, curbing corruption is critical for economic prosperity and political stability in democracies.

However, until now cross-nation studies have failed to produce conclusive findings on whether corruption has a negative impact on popular political support and thus called into question whether this institutional approach could travel across national contexts, particularly in those non-democratic regimes (e.g., Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Treisman, Reference Treisman2007; Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charronforthcoming). A review of the literature suggests that the relationship between corruption and popular political support can be shaped and sometimes complicated by two factors: the politicization of corruption and forms of corruption. In the first place, corruption and its public exposure may be shaped by political competition among parties in democracies. It is argued that the exposure of official corruption is markedly politicized amid intense party competition (Bågenholm, Reference Bågenholm2013; Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017). In electoral cycles, political parties often accuse their opponents for political corruption to gain public support. The recent emergence of many anti-corruption parties (ACPs) confirms the trend of politicizing corruption. Bågenholm (Reference Bågenholm2013), for instance, finds that the anti-corruption performances of ACPs may greatly enhance their positions in many European governments. In light of this, when corruption is highly politicized and closely integrated into electoral competition, the exposure of official corruption does not necessarily undermine the public's diffuse support for democratic regimes. Rather, the politicization of corruption in democracies may restore the public's faith in democratic accountability.

Besides the politicization of corruption, scholars have found that the types of corruption can affect the public's diffuse support for democratic regimes. Bauhr and Charron (Reference Bauhr and Charronforthcoming), for instance, distinguish between two types of corruption. One type of corruption refers to common corruption scandals among elected officials, and the other type is ‘grand corruption’ among ‘the highest levels of government that involves major public sector projects, procurement, and large financial benefits among high-level public and private elites’ (Bauhr and Charron, Reference Bauhr and Charronforthcoming, p. 2). Based on data from a large survey of 85,000 individuals in 24 European countries, they find that rather than common official corruption cases, it is egregious grand corruption that severely detrimental to the public's attachment to the democratic institutions. Specifically, grand corruption fundamentally undermines democracies by alienating the public and engendering a deep divide between insiders, potential beneficiaries of the system, and outsiders, left on the sidelines of the distribution of benefits. Thus, the negative impact of corruption on the public diffuse support for democratic regimes is contingent on the particular type of corruption.

In authoritarian regimes, the relationship between popular political support and regime support is even more complicated as suggested by an institutional approach. This has a lot to do with the fact that authoritarian regimes lack the basic accountable institutions and rely more on campaign-style strategy to curb corruption. While scholars like Huntington (Reference Huntington1968) argue that corruption is a necessary evil in authoritarian contexts, authoritarian regimes commonly respond to rampant corruption by launching anti-corruption campaigns and cleanups (Gillespie and Okruhlik, Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1991; Holmes, Reference Holmes1993; Manion, Reference Manion2004; Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2005; Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017). However, the research on anti-corruption efforts of authoritarian regimes is still at its nascent stage. Due to the scarcity of data, there are much fewer empirical studies on corruption in authoritarian countries than those in democracies. Some earlier studies point to a potential positive link between anti-corruption efforts and the popular support for non-democratic regimes. Chen (Reference Chen2004), for instance, shows that anti-corruption efforts are perceived as an integral part of the public's evaluation of government performance and could positively contribute to their diffuse support to the authoritarian regimes.

Yet, recent studies suggest that such a positive relationship could be also complicated by politicized anti-corruption campaigns and corruption associated with different levels of government. After examining anti-corruption data in China between 1996 and 2012, Zhu and Zhang (Reference Zhu and Zhang2017) show that intra-elite power competition can markedly increase investigations of corrupt senior officials as well as the intensity of anticorruption propaganda. On the other hand, Wedeman (Reference Wedeman2004, Reference Wedeman2005) find that governments in China have target anti-corruption campaign mainly at low- and mid-level cadres. Although such strategic campaigns have been proven largely ineffective (Manion, Reference Manion2004; Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2004), they help to steer the public's attention from grand corruption to petty corruption and hence maintain the public's support for the central government and the regime. Finally, a recent survey conducted by Sun and Yuan (Reference Sun and Yuan2017) in 2015 points to a more nuanced picture, suggesting mixed effects of campaign-style strategy on regime legitimacy. They find that while anti-corruption campaigns could enhance the public's satisfaction with the central governments, such positive effects failed to ‘trickle down’ to local governments. In the long run, the public's dissatisfaction with corruption at the local level could undermine their support for the regime as a whole.

In sum, the studies mentioned above suggest that the key motivation for government to make efforts to fight corruption is to help boost popular political support. Due to the lack of the basic accountable institutions, authoritarian regimes often rely on campaign-style movements to fight or curtail corruption. Unfortunately, until now there are few studies that have systematically explored how anti-corruption campaigns launched by authoritarian governments could affect the public's political support.Footnote 2 Moreover, there is still a lack of understanding of how the impact of government anti-corruption campaigns varies with the type of corruption that governments try to fight or curtail on the public's political support.

2. Anti-corruption campaigns and political support in China: central vs local governments

Contemporary China, given its rampant corruption and repeated anti-corruption campaigns, provides a perfect laboratory for a systematic examination of how campaign-style anti-corruption could affect the popular political support in authoritarian countries. First, for scholars interested in the relationship between institutional quality and socioeconomic development, China emerges as a puzzling ‘paradox’ (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2015). As noted by Rothstein (Reference Rothstein2015), despite China's rampant corruption at various levels, it has managed rapid economic growth and made marked improvements in various areas of human well-being. For many, the discrepancy between the established theory about ‘good governance’ and the economic development in China has created ‘the hardest contemporary nut that comparative political scientists have to crack’ (Ahlers, Reference Ahler2014; also see Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2015).

Second and more importantly, in contrast to many democracies distressed by declining political trust (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004), the central government in authoritarian China has seemed to maintain a high level of political trust since the early 1990s, as indicated in many survey studies conducted in China (e.g., Shi, Reference Shi2001; Chen, Reference Chen2004; Tang, Reference Tang2005; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2009). Yet, what makes the case of China more perplexing is that despite these survey-study findings, the number of social unrests and popular resistances related to corruption and malfeasance of government officials at the local level has reportedly surged in the country (e.g., O'Brien and Li, Reference O'Brien and Li2006; Cai, Reference Cai2008; Chen and Lu, Reference Chen and Lu2011). This discrepancy between the survey-study findings about popular support for the central government and the reports on unrests in many locales seems to suggest that decentralization of administrative power from the Center to local government and party institutions might have caused somewhat different levels of popular political support for the central and local governments.

It should be also noted that while many extant studies have indicated that political trust tends to vary significantly with the vertical dimensions in China, there has been no consensus on how it varies among these studies. On the one hand, some studies suggest that the public tends to have weaker confidence in lower-level governments (e.g., Zhou, Reference Seligson2010). This is because lower-level governments, though enjoy considerable autonomy, are still under effective control of upper-level governments, answering only to their immediate superiors. This kind of ‘decentralized authoritarianism’ makes local governments insulated from public pressures and encourages the implementation of unpopular policies, which inevitably cause public disaffection against lower-level governments (Landry, Reference Landry2008). On the other hand, some scholars find that decentralization in the forms of grassroots democracy and localism can help build trusting relationships between citizens and local cadres (e.g., Jennings and Zeitner, Reference Jennings and Zeitner2003; Manion, Reference Manion2006; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Huhe, Lu, Guo and Hickey2009), and thus grassroots governments are likely to enjoy higher levels of political trust.

More recently, in an original nationwide survey conducted in 2014, Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Shen and Yan2017) systematically examine whether ordinary Chinese distinguish primarily along the central–local dimension or whether they also distinguish between different apparatus of the party-state like the people's congress, the party branches, and the executive branches of the governments. Their analyses suggest that while there are only marked differences between people's political support for the central and local governments, ordinary Chinese have similar levels of trust in the party, the governments, and the people's congress. In other words, the only notable division in public opinions toward the party-state is the one between central and local states. Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Shen and Yan2017) further coin a term of ‘local legitimacy deficit’ to describe the legitimacy problem in China, that is, the central government receives consistently higher levels of support and trust than the local ones.

Given the unique legitimacy challenge faced by the CCP regime, China can serve as a crucial case for our understandings of the impacts of campaign-style strategy on popular political support. In this study, we explore how the campaign-style anti-corruption affects central and local state legitimacy by relying on a longitudinal dataset of three waves of nationwide surveys in China. This longitudinal approach not only could help us better identify the actual impacts of anti-corruption campaigns on the legitimacy of the CCP regime, more importantly, it also allows us to examine the very trends of the legitimacy and to compare effects of the campaigns with some other long-term legitimacy correlates.

3. Xi's anti-corruption campaign: another campaign as usual?

To explore the impact of anti-corruption campaigns on popular political support in China, this study pays special attention to the recent campaign launched by Xi Jinping, the current paramount leader of the CCP and the Chinese government. After assuming the leadership of the Communist party in November 2012, Xi launched a new large-scale anti-corruption campaign. There are at least three important reasons that Xi's anti-corruption campaign is of particular interest. First, as noted by Manion (Reference Manion2016), ‘by any number of measures,’ Xi's anti-corruption campaign is ‘the most thoroughgoing in the party's history’ (p. 5). The campaign was initiated in later 2012, and until now, there has been no sign that the current anti-corruption campaign will stop. Rather, the intensity of the campaign has increased continuously. In other words, while the anti-corruption campaigns launched before Xi are considered ‘short bursts of intensive enforcement,’ Xi's campaign is by no means an episodic burst but is a norm in today's Chinese politics.

Second, unlike previous campaigns, Xi's campaign targets heavily on senior officials. As described by Wedeman (Reference Wedeman2004, Reference Wedeman2005; also see Manion, Reference Manion2004; Sun and Yuan, Reference Sun and Yuan2017), the Party's earlier campaigns tend to depress the rate of low-level petty corruption much more than ‘high-level, high-stakes corruption and may even have an “inflationary” effect by pressuring corrupt cadres to demand larger bribes’ (Wedeman, Reference Wedeman2005, p. 95). In sharp contrast, Xi distinguished his anti-corruption campaign from previous ones by pledging to target on both ‘flies’ (i.e., low- and mid-level officials) and ‘tigers’ (i.e., senior and high-level officials). The published records from the Central Discipline Inspection Committee (CDIC) and its local Discipline Inspection Committees (DICs) in the party also show sharp increases in numbers of officials convicted of corruption at and above the vice-ministerial level.

Third, a final distinct feature of Xi's anti-corruption is that Xi has introduced a series of institutional changes. For instance, CDIC regularly dispatched discipline inspection teams directly to local governments for regular inspections of disciplinary affairs and investigations of specific official corruption cases. These teams report directly back to the CDIC. The CDIC's direct inspections and investigations at the local levels through the inspection teams have forced local leaders to prioritize anti-corruption campaigns. Such institutional changes, as observed by Manion (Reference Manion2016), have ‘reduce[d] bureaucratic opportunities for generating bribes’ throughout the party-state system (p. 10). Consequently, many China observers argue that Xi's campaign signals the Party's genuine commitment ‘to keep power in cage of systemic checks’ (e.g., Manion, Reference Manion2016)

On the one hand, Xi's ongoing anti-corruption campaign could be interpreted as a genuine commitment to curb corruption in China. This interpretation has been substantiated by many official media converges on convictions of corruptions committed by both ‘flies’ and ‘tigers.’ As a result, one would expect that Xi's anti-corruption helps to boost the public's support for the regime. On the other hand, we cannot rule out an alternative interpretation that Xi's campaign is a disguised purge of factional competitors within the Party and government (e.g., Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017). Thus, the frequent exposures of grand corruptions associated with top-level officials could be seen as political persecutions and hence decrease the public's faith in the political system.

As we mentioned above, few empirical studies have directly addressed the impact of the type of anti-corruption campaign on popular political support in authoritarian settings. To fill this gap, we subject the competing interpretations and expectations about Xi's anticorruption campaign to empirical test in this study.

4. Data, measurements, and empirical approach

This study relies primarily on public opinion data from three waves of nationwide surveys collected by the Center for Public Opinion Research of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Each of these random telephone surveys encompassed 36 large cities throughout China. Besides Beijing, each survey includes 30 provincial capital cities and five cities that enjoy provincial-level status in the state economic plan.Footnote 3 These cities represent different regions and different levels of economic development. Two of these surveys were carried out in March 2011 and 2012 during Hu Jintao's administration, and one was conducted in March 2015 during Xi Jinping's administration. The sampling frame includes both landline and cell phone numbers in those cities. The Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) system generated random telephone numbers. Trained graduate and undergraduate students at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and several other surrounding universities in Shanghai conducted the anonymous survey.

We combine the three waves of nationwide into an integrated longitudinal dataset based on the cities in which the surveys were carried out. For summary statistics, see the Appendix. As shown in the Appendix, the key demographics of the integrated dataset are comparable with those of the 2010 census. This longitudinal dataset allows us to trace overall trend of popular political support from Hu to Xi. We thus can better examine impacts of both the CCP's campaign-style anticorruption as well as some other key legitimacy correlates. In the following part of this section, we introduce our measurements of central and local state legitimacy, the regime's campaign against ‘flies’ and ‘tigers,’ and other important factors that could shape the popular support of the regime.

4.1. Dependent variables: political trust in central and local governments

In this study, we use trust in the Central and local governments to gage political support among our respondents. Political trust is commonly defined as citizens' basic belief that political actors or institutions are ‘producing outcomes consistent with their expectations’ (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2004, p. 9). Some earlier empirical studies on political trust, strongly influenced by Easton's (Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975) concept of ‘diffuse support,’ were also focused primarily on citizens' support for a set of institutions established and values advocated by a political regime (Citrin, Reference Citrin1974; Miller, Reference Miller1974; Muller and Jukam, Reference Muller and Jukam1977; Abramson and Finifter, Reference Abramson and Finifter1981; Weatherford, Reference Weatherford1987).

Moreover, empirical evidence collected in North America and Western Europe suggested that people's trust in specific political actors and institutions was more likely to be affected by immediate causes such as perceptions of the economy, political scandals, and ongoing policy debates (e.g., Kornberg and Clarke, Reference Kornberg and Clarke1992; Chanley et al., Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Anderson and LoTempio, Reference Anderson and LoTempio2002; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002). More interestingly, these studies find that people do not trust various political institutions equally, with some institutions being considered more trustworthy than others (e.g., Kornberg and Clarke, Reference Kornberg and Clarke1992; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003). Since the early 1990s, an emerging trend in the literature has been to conceptualize political trust as a multidimensional phenomenon. This conceptualization differentiates peoples' trust in different institutions and actors in different issue areas (e.g., Kornberg and Clarke, Reference Kornberg and Clarke1992; Weatherford, Reference Weatherford1992; Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Norris Reference Norris2011).

In this study, we developed our measurement of political trust in different levels of the Chinese political system – the national and local governments. We used the following statement to measure the respondent's trust in each level: ‘I believe that the Central government (or my local municipal government) is always acting in my best interests.’ For each question, the respondents were asked to assess their trust on a 5-point scale, where ‘strongly disagree’ is scored ‘0’ and ‘strongly agree’ is scored ‘4.’ More specifically, we use the term ‘Central governments’ (i.e., 中央政府) to refer to central political institutions. As shown in the nationwide survey by Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Shen and Yan2017), ordinary Chinese expressed similar, if not identical, levels of political trust in central political institutions like the Party, the government, and the people's congress, and people's political trust could serve as a reliable indicator of the central state legitimacy.

For local state legitimacy, as highlighted by Sun and Yuan (Reference Sun and Yuan2017), local governments in the Chinese context could be referred to a range of subnational governments like provincial, municipal (provincial capital), and sub-municipal governments. Our choice of the measurement of local governments thus could strongly affect our subsequent analyses and finally our understandings of the impacts of CCP's anti-corruption campaigns against ‘tigers’ and ‘flies.’ We focus on the municipal governments (provincial capital) for the following reasons. Frist, as explained in Section 4.2, in our study we define ‘tiger’ as those provincial heads (i.e., provincial governors and secretaries of provincial party committees). For residents living in provincial capitals, corruption investigation against provincial heads tends to strongly shape their attitudes toward both central and local governments. Second, our focus of provincial capitals is also consistent with our measurement of campaigns against ‘flies,’ which is an aggregation index of number of officials at and above county/division levels investigated by the provincial procuratorates. Finally, for our three longitudinal and nationwide surveys, a focus on provincial capitals ensures both comparability across provinces and consistency over time.

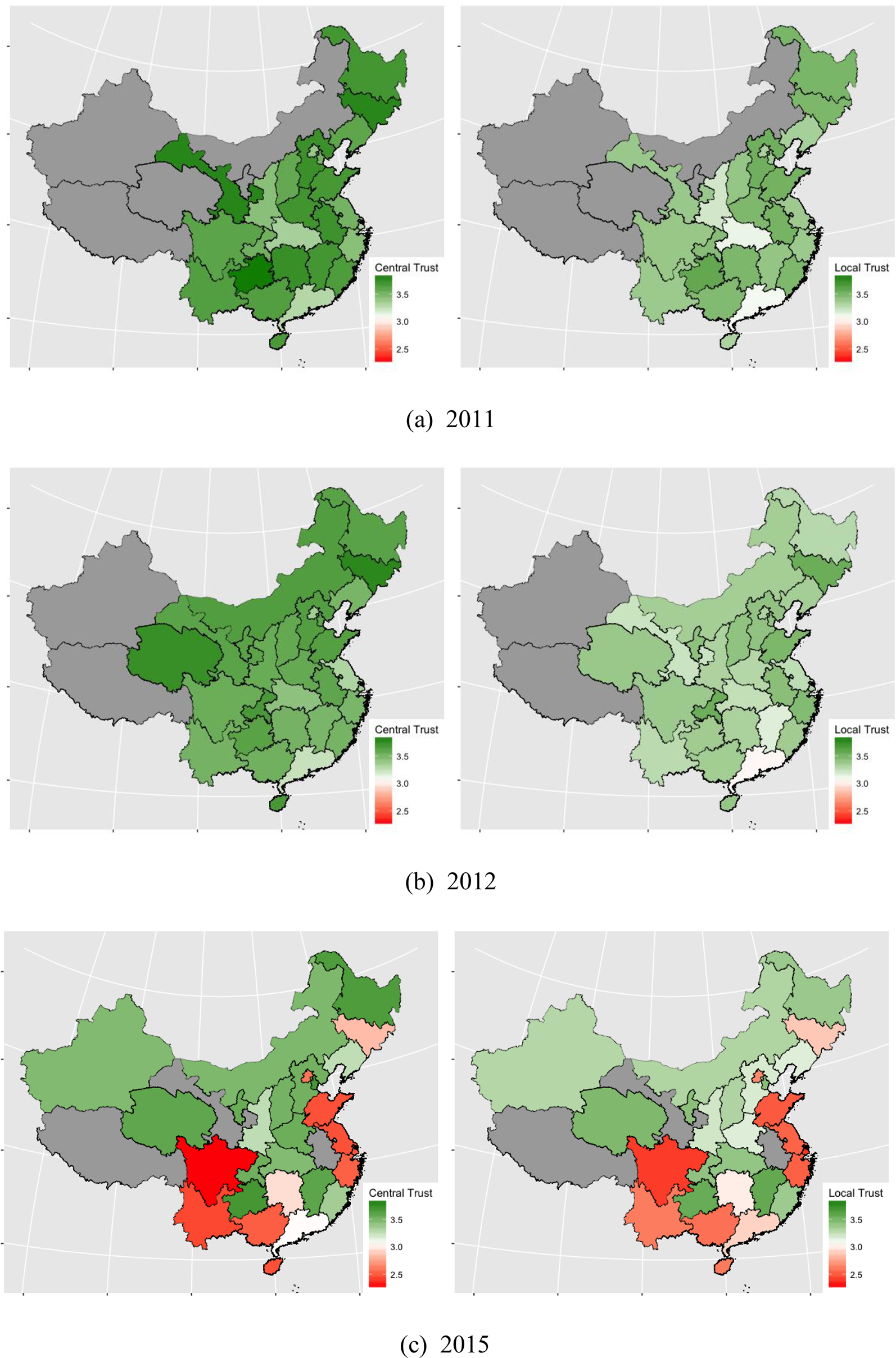

Figure 1 maps the public's reported political trust in central and local governments across the three surveys from 2011 to 2015. Three important findings stand out. First, the overall results indicated that the levels of political trust declined as the levels of government institutions descended. Specifically, among our respondents, the degrees of trust in central government were higher than those in authorities at the local level. These findings suggested that the majority of our respondents had stronger confidence in the national authorities. This finding is consistent with the pattern observed in rural China (Li, Reference Treisman2004, Reference Tang2008). Second, we found that across the three surveys, the public's trust in both the central and local governments declined steadily over time. Particularly, the loss in political support is markedly evident from Hu's administration (i.e., 2011 and 2012) to Xi administration (i.e., 2015). While Xi's anti-corruption campaign might exert some positive impacts on popular support, as we discuss in detail in Section 3.3, there could be some other long-term factors at work as well (e.g., Chen, Reference Chen2004). Finally, Figure 1 also reveals a sharp regional disparity in political trust. Coastal provinces like Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Guangdong seem to report much weaker political trust than those inland provinces. Moreover, the regional disparity has been intensified under Xi administration.

Figure 1. Political trust in central and local governments: (a) 2011, (b) 2012, and (c) 2015.

4.2. Anti-corruption campaigns: flies and tigers

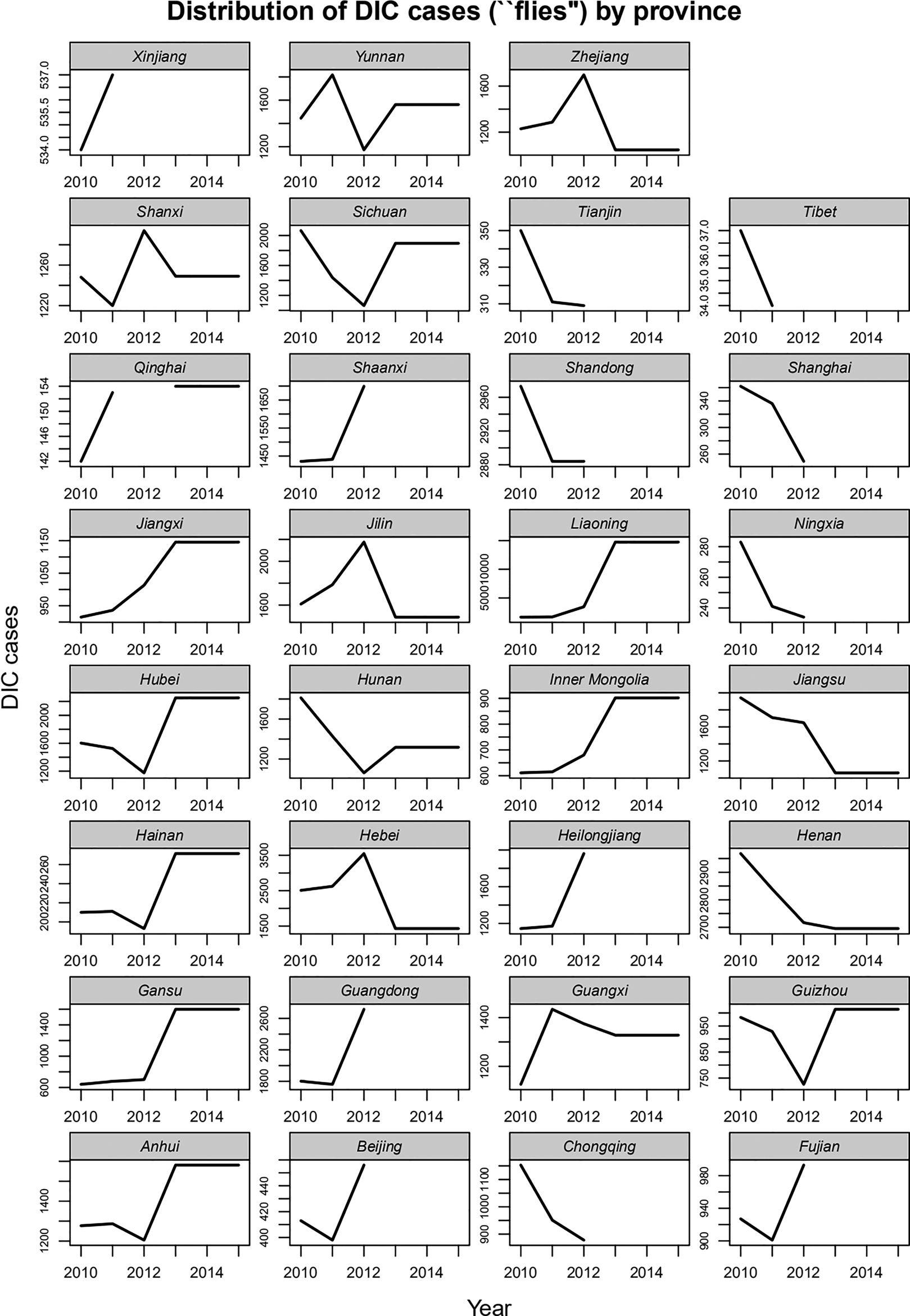

To investigate the varying impacts of different types of anti-corruption campaigns, we gage the effects of the campaigns against both ‘flies’ and ‘tigers.’ Specifically, for low- and mid-level officials, we rely on data published in the Procuratorate Statistical Yearbooks. The Yearbooks report the sheer number of officials at and above county/division levels in China investigated by the provincial procuratorates. Consider the variation in the sizes of provincial governments, we weight the sheer number of reported cases by the number of county-level units in each province. The same dataset has been widely used in earlier studies (e.g., Zhu and Zhang, Reference Zhu and Zhang2017) and has proven a reliable measure of the magnitude of anti-corruption campaigns against local officials. In Figure 2, we illustrate the trends of campaigns against ‘flies’ from Hu to Xi by province, and we can find divergent overtime patterns. While in Xi era there were some significant increases in case numbers in provinces like Anhui, Gansu, and Inner Mongolian, provinces like Zhejiang, Hunan, and Jiangsu have witnessed marked declines. This in turn could lead to quite different impacts on local state legitimacy across provinces.

Figure 2. DIC cases by provinces, 2010–2015.

As for ‘tigers,’ we collected and categorized all the reported investigations related to officials at and above the provincial level. Since main interest is the provincial variations, we limit our focus to provincial heads and remove cases associated with officials in the central government and PLA officers. We expected investigations against provincial heads could affect how the public in provincial capitals perceive the central and local governments.Footnote 4

4.3. Other key legitimacy correlates and controls

In this study, we also incorporate key legitimacy correlates as emphasized in the extant literature. First, we asked our respondents about their assessments of public goods provision by the municipal governments, ranging from education to transportation. We then combined their answers and formed an aggregated index of their overall evaluation of government performance. Following the findings of extant studies (e.g., Chen, Reference Chen2004; Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Shen and Yan2017), we expect that people's assessment of government performance is positively associated with their support of local and central governments. Second, as shown by Chen and Lu (Reference Chen and Lu2011), the economic dependency on the party-state could strongly shape the public's attitudes toward the regime. In this study, we collected the share of state economy in each province to gage the relative levels of state dependency. Finally, we included a range of key controls like hukou status, CCP membership, education, income, and gender. All these controls have been found significantly correlated with ordinary people's political support in China.

4.4. Empirical approach

Our key independent variables are provincial-level indicators of anti-corruption efforts of the CCP regime: the overall numbers of cases reported by DIC (i.e., flies) and whether provincial heads were investigated (i.e., tigers). Unfortunately, due to available data, we are unable to compile corruption cases at the prefecture level. We regress these two key indicators against respondents' reported trust in the central and local governments. To better capture the longitudinal impacts of Hu and Xi's different anti-corruption campaign and to better control for omitted variables bias due to the unobserved heterogeneity, we introduce fixed-effect panel analysis with province and year fixed effects. The two fixed effects absorb time-invariant heterogeneities across the surveyed cities and aggregate shocks that affect all cities in a given year, respectively.

5. Analyses and results

Our analysis of the impact of the CCP's anti-corruption campaigns proceeds in two steps. First, we focus on the Hu era, that is, the first two waves of surveys (i.e., those in 2011 and 2012) and analyze how anti-corruption campaigns against ‘flies’ affects the public's support for the central and local governments. Second, we extend our analysis by including the 2015 wave of survey. This allows us to explore how Xi's crackdown on ‘tigers’ alters the popular political support.

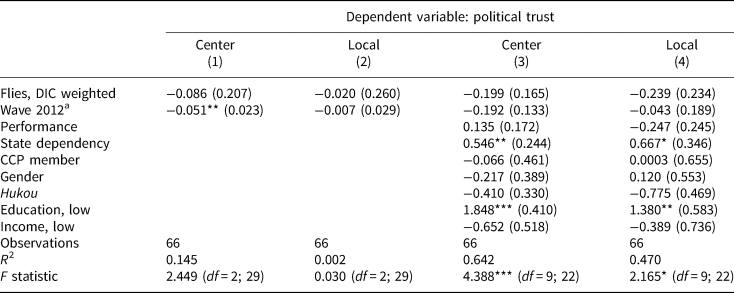

Table 1 presents the results of our analysis of the relationship between anti-corruption campaigns and the public's political trust. Two important findings stand out. First, there was no significant relationship between anti-corruption against ‘flies’ and the popular political support. This finding is consistent when we vary the measures of anti-corruption against low- and mid-level officials. Specifically, from models 1 to 4, the coefficients of ‘flies’ are consistently insignificant, pointing to a null relationship between campaigns against flies and popular political support. One possible explanation is that under Hu administration the public did not render their support to the government based on its anti-corruption efforts. Second, there was a significant decline in the public's political trust in the central government from 2011 to 2012. The significance of the association between the two waves in political support diminished when some control variables were incorporated.

Table 1. Anti-corruption campaigns and political trust under Hu administration

a The wave 2011 as the reference.

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

On the other hand, we do find some other key legitimacy correlates exerting significant impacts on people’ trust in both local and central governments. First, consistent with findings of Chen and Lu (Reference Chen and Lu2011), our analyses show that the share of state economy correlates significantly and substantially with political trust in both local and central governments. People who live in provinces with larger presence of state economy are more likely express strong popular support. Second, we find that the education levels also strongly affect people's political trust. More specifically, people in cities with lower education attainments are more likely report higher levels of trust in local and central governments. Finally, we find that people's assessment of government performance fails to exert a significant impact on popular political support, either local or central. One possible explanation is the very unsustainability of performance legitimacy. As emphasized by Zhao, performance legitimacy, due to its reliance on concrete promises, is more likely to wane overtime than institutional legitimacy like democracy. Together, our findings help reveal some long-term drivers underneath the decline of popular political support in China. In the Hu era, while ever-increasing education levels and a booming private economic sector (i.e., the decline of state economy) have led to lower political trust, anti-corruption campaign against flies fails to reverse the trend.

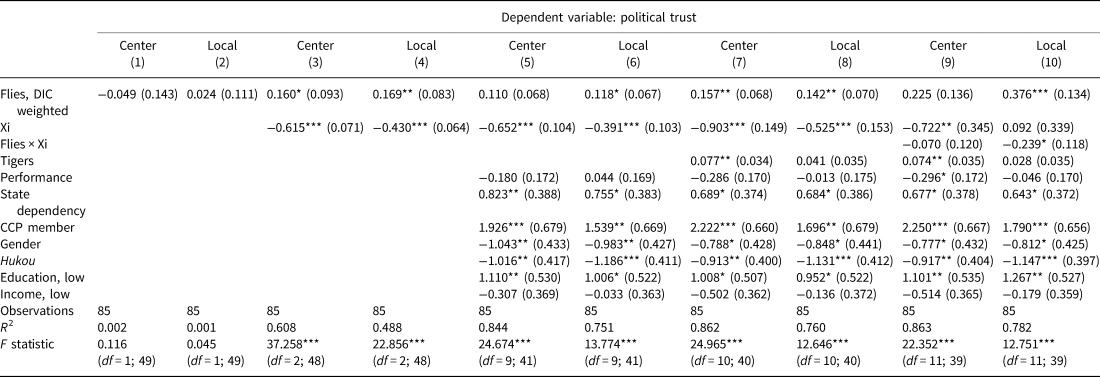

Table 2 reports our extended analysis that includes the 2015 wave of survey, i.e., the Xi era. It reveals some interesting dynamics under Xi administration. First of all, we find that, consistent with findings presented in Table 1, the popular political support in China declined steadily over time. From model 1 to 8, the coefficients of the Xi era are consistently significant and negative. In other words, compared to Hu administration, Xi administration has witnessed marked drop in the public's political trust, both in the central and local governments. Second, our analyses show that the public does respond positively to Xi's anti-corruption against the ‘tigers,’ senior and high-level officials. In model 7, we can find that the case number of tigers is positively and significantly associated with political trust in central governments. Comparatively speaking, provinces with convicted provincial officials tend to report stronger support in the central government. But there is no significant correlation between the number of convicted provincial officials and the public's trust in local governments. Third, from models 3 to 8, we could find strong and consistent effects of campaigns against flies on people's trust in both local and central governments. In other words, if we take both the Hu and Xi eras into account, campaigns against flies do exert positive impact on popular political support.

Table 2. Anti-corruption and the public's political trust from 2011 to 2015

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

We further included interaction effects between the Xi era and the cases of ‘flies’ (models 9 and 10) to explore whether Xi's campaigns are different from the ones of the Hu era. In models 9 and 10, we find divergent impacts of such an interactive time (i.e., Flies × Xi) on trust in central and local governments, respectively. On the one hand, as for respondents' trust in central government (i.e., model 9), we can find that the ‘Flies × Xi’ interaction term is not statistically significant. This indicates that Xi's campaign against ‘flies’ has not been able to increase people's support of the central governments. On the other hand, as shown in model 10, the ‘Flies × Xi’ interaction term bears a negative and significant association with respondents' trust in local governments (i.e., β (Flies×Xi) = −0.239). Taking this interactive effect together with the general positive impacts of the campaign against ‘flies’ (i.e., β Flies = 0.376), the net effect of the campaign against ‘flies’ in Xi era is, β Flies + β (Flies×Xi) × 1 = 0.376 +(−0.239) × 1 = 0.137. The value of this net coefficient from model 10 is smaller than the general effect of the campaign against ‘flies’ across Hu and Xi era (i.e., 0.142) in model 8. Juxtaposing models 8 and 10, we thus can conclude that while campaigns against flies helps to increase people's political support, particularly for local governments, its positive impacts on popular support are diminishing in Xi era.

Finally, similar to our findings from Table 1, we find strong and significant impacts of some other legitimacy correlates, dwarfing the impacts of CCP's anticorruption campaigns. First, from models 5 to 10, state dependency correlates significantly and positively with popular support of both local and central governments. This in turn suggests that a booming private sector could significantly undermine the regime legitimacy. Second, we find that respondents in cities with a higher share of urban hukou status tend to report lower levels of local and central trust. In other words, rapid urbanization and a more pluralized society lead to lower popular support of the CCP regime. Third, the higher education levels are strongly associated with local trust in both local and central governments. Finally, consistent with results of Table 1, we find waning performance legitimacy throughout the Hu and Xi eras. Together, these results suggest that despite some positive effects of CCP's anticorruption campaign, the popular political support is still in steady decline because of some other long-term factors like a thriving private economic sector, an increasingly pluralized society, rising education attainments, and the unsustainable performance legitimacy.

6. Conclusion

By integrating anti-corruption data with nationwide surveys conducted in 2011, 2012, and 2015, this study explores how the CCP's crackdown on flies and tigers affect the public's trust in central and local governments. Our analyses suggest that the public's trust in both central and local governments is declining steadily throughout Hu and Xi eras, despite the fact that the public does react positively to Xi's anticorruption campaign. Xi's anti-corruption, particularly his crackdown on senior and high-level officials, helps boost the public's trust in the central government. However, the legitimacy boost delivered by Xi's anti-corruption campaign has failed to stop this general declining trend of political support. In other words, while the state is effective and successful in promoting popular political support by curbing corruption, it fails to forestall the effects of some long-term factors like a thriving private economic sector, an increasingly pluralized society, rising education attainments, and the unsustainable performance legitimacy. Our study thus reveals these key legitimacy challenges faced by the CCP regime. However, as one of the first few studies that have systematically examined the impacts of anti-corruption campaign, our study is inevitably limited due to problems like data available. More studies are thus called for to explore popular political support in China.

Data

The replication codes and data will be available for replication.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/2WCFUM.

Appendix: Three waves of survey and summary statistics

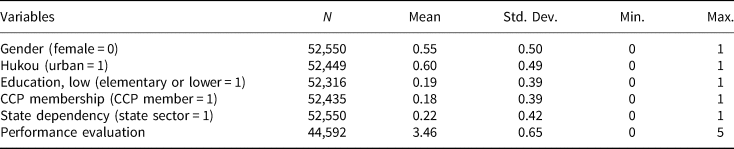

The three waves of surveys were conducted in 2011, 2012, and 2015, respectively, by the Center for Public Opinion Research of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU), a reputable survey institute in China. The CATI system generated random telephone numbers. Trained graduate and undergraduate students at SJTU and from several other universities in Shanghai conducted the survey. The telephone surveys encompassed randomly selected respondents from 31 major cities throughout mainland China. Along with Beijing, these cities include municipalities directly under the central government, and provincial capital seats. These cities represent different regions and different levels of economic development. The sampling frame includes both landline and cell phone numbers in these cities. We report the summary statistics of key covariates at the individual level in Table A1.

Table A1. Summary statistics of key covariates at the individual level

Juxtaposing the statistics of some key demographics in Table A1 with those from the 2010 Census of China, we could find that the samples of the three surveys are largely comparable to the national sample in terms of gender ratio. While 55% of the respondents of the three surveys are male, the percent is 51.3. In terms of education attainment, given the urban focus of the three surveys, the respondents in our dataset tend to have higher education attainments with about 19% of elementary education or lower. On the other hand, in the 2010 Census of China, about 30% population reported elementary education or lower. Taking these together, we can find that the samples of three surveys can provide important insights about the public opinion in urban China.