Freed slaves were significant agents of social, cultural, and religious change in Africa. Inspired by Christian providentialism and emotional connections with their African ancestral heritage, ex-slaves in Britain and America provided much of the impetus for missionary contact with Africa in the nineteenth century and some subsequently returned to Africa as missionaries.Footnote 1 Catholic Orders such as the Holy Ghost Fathers, the White Fathers, and the Protestant Universities Mission to Central Africa used purchased and freed slaves in their attempts to socially engineer Christian communities.Footnote 2 More significantly, Christianised ex-slaves played a key role in the movements of mass conversion that traversed Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The impact of former slaves was most profound in West Africa where more than 70,000 slaves were freed by the Royal Navy in Sierra Leone following the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Dispersed into Christian villages around Freetown, many adopted Christianity and subsequently returned home along the West African coast as agents of a Christian modernity. Considering themselves ‘Black English’ these returnees played a leading role in mediating British policies and practice in the era of imperialism and colonial conquest and, according to Vivian Bickford-Smith, influenced change at ‘the level of religious belief, dress, agricultural practices, domestic architecture, privately owned objects, diet and the sense of self in relation to society’.Footnote 3

This article extends the story of freed slaves to the frontier between Angola and Belgian Congo, where, save for a few glimpses, their historical experience has been largely ignored.Footnote 4 It examines the movement of ex-slaves who had been taken from Luba, Songye, and Lunda territories in what became Belgian Congo and marched to Bié in Angola by Ovimbundu slavers between 1870 and the early 1900s. They were Christianised through contact with Euro-American missions while labouring in Angola. The former slaves returned home in the 1910s following the abolition of slavery in the Portuguese Empire to found a Christian movement in south-east Belgian Congo which introduced radical social and cultural change. But such change came with contradictions and costs; this article considers the tensions in the returnees’ social positions and experiences.

As actors in a colonial setting, missionaries often manifested a somewhat schizophrenic attitude towards Africans, seeking at once to preserve the past, promote economic change, and protect them from the worst effects of modernity. At times, freed slaves’ notions of respectability, which fused Christian ideals with older African notions of rank and honour, conflicted with missionary conceptions of respectability, particularly with regard to gender norms. The former slaves’ sophistication in diet, deportment, and dress ran counter to the demands of Christian humility and their own evangelical initiatives conflicted with loyalty to new missionary patrons. Moreover, their rejection of the uncivilised ‘other’ ran counter to the demands of Christian fellowship. And while they were indebted to missionaries for patronage and support, the trauma of enslavement coupled with missionary racism and paternalism produced what missionaries described as a ‘nameless grudge’ against authority.

Ideas of salvation provided the former slaves with an understanding of their experience of captivity and return, and a means of reimagining their social position and spiritual destiny. Although missionaries celebrated in their writings the returnees’ Christian endeavours, conflicts soon arose over authority and what constituted respectable behaviour. Following an examination of former slaves’ experiences of enslavement and return, the middle sections of the article considers these conflicts. The final part will examine how tensions with missionaries were exacerbated by the memory of servitude and the disorientation of return. One of the returnee leaders, Kaluwashi, severed relations with missionaries. Other former slaves sought alternative means to status and authority through Independent Christian movements or by mobilising their traditional connections in local society.

A word is needed about sources. The missionary materials used in this article must be viewed with what J. D. Y. Peel terms ‘a hermeneutic of deep suspicion’ given that they were created by European Christians imbued with the rhetoric of civilisation and who were mindful of the metaphorical power of stories of slavery and redemption.Footnote 5 The primary missionary source analysed is the bi-monthly journal published by the Congo Evangelistic Mission (CEM), first known simply as Report of Work (RW) and then, after 1922, as The Congo Evangelistic Mission Report (CEMR). This journal aimed to convince readers back home of the need to donate funds to and pray for the work of the CEM. Much of the content was what Nancy Rose Hunt describes as ‘evolutionary stories of progress’ that worked in terms of simple oppositions: darkness to light, savagery to civilisation, heathens to Christians.Footnote 6 But not all missionary texts were triumphal. As Peel has shown in his outstanding study of the encounter of the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) amongst the Yoruba, the sources often ‘spoke against their authors’. In order to vindicate their work of evangelism, some missionaries recorded ‘the hostility, indifference and mockery with which their preaching was received’.Footnote 7 Others shared their heartaches, doubts, and failures in order to instruct readers on the costs of Christian service. These disturbances to missionary narratives offer indirect evidence of how Africans responded to Christianity. They are supplemented by yet more explicit private correspondence to family, friends, and prayer partners in the idiom of the embattled psalmist, who shared frustrations and failings as well as successes. Protestant mission periodicals reveal much about how missionaries viewed Africans, traditional and Christian, and what they found mystifying about them. They also, however, include African voices in order to demonstrate their evangelical successes. As Terence Ranger observed in his work on American Methodist missionaries (who are also considered in this article), evangelical religion placed a premium on recording the authentic heartfelt public confessions, testimonies, and sermons of converts as evidence of the saving power of the proclaimed Word.Footnote 8 At times African voices were stereotyped or their dialogues with missionaries became missionary monologues, but African words were also cited verbatim and some evangelists contributed articles. Apart from the need to assert authenticity, missionaries were often short of copy and African words were both compelling and readily available. The CEMR was produced and edited in Katanga. Missionaries, facing many challenges, generated this material and the scale and scope of their struggles is attested by the fact that some articles and images shocked metropolitan audiences.Footnote 9

Missionaries also reflected on the lives of their converts through hagiography. These texts asserted the lasting effects of missionary labours by celebrating the lives of key converts as founders of the African church. Missionaries relied on these figures as a companions and intermediaries. Marcia Wright, who has made use of Brethren hagiographies (also examined here) to reconstruct the lives of ex-slave women, aptly describes them as accounts by ‘intimate outsiders’. Although these hagiographies took the form of empathetic ‘tales’, highlighting social evils (in this case the Afro-Portuguese and Swahili slave trades), Wright observes that they surpassed supposedly scientific accounts in capturing the ‘dynamics of real life and revealed interactions that were erased in standard ethnographic formats’.Footnote 10

African Christians created their own intellectual traditions, particularly through canonical history. The most important one for this study is Ngoie Marcel's The Life of Shalumbo (1968) which is a biography of a Songye ex-slaver and Christian convert who led one of the parties of returnees and played a prominent role in their work in Belgian Congo. A CEM primary school headmaster, church leader, and descendant of Shalumbo, Marcel, exemplified the middle figures who form the core of Hunt's analysis discussed below. His text addresses the context of postcolonial Zaire when the Songye section of the CEM split from Luba section and sought to assert its indigenous African credentials. It can also be read as a Christian tribal history, a statement of Songye civilisation in the face of colonial and missionary preference for the Luba. Marcel emphasises Shalumbo's role as the church's ‘founder’ alongside other Songye pioneers and decentres missionary agency. Nevertheless, the text resembles missionary-authored hagiographies in its exhortation to emulate the religious life of the ex-slaver-turned-evangelist. It is relentlessly heroic in its portrayal of the returnees’ fortitude in the face of adversity and pagan superstition. In a world in which missionaries and African converts had deep and meaningful daily interactions and regularly shared testimony, the mutual exchange of discourses was inevitable. However, Marcel's text also incorporates elements from earlier honour codes, stressing Shalumbo's military prowess and courage in defence of his people prior to his conversion. Unsurprisingly, it remains silent on Shalumbo's complicity in the slave trade.Footnote 11

Other former slaves recounted their stories to their descendants and Christian brethren, some of whom were interviewed by this author and, earlier in the 1980s, by David Garrard, a CEM missionary, who wrote a doctoral thesis on the movement.Footnote 12 These oral sources suggest where missionary narratives of African return, redemption, and respectability were shared by former slaves, and where they were ignored or rejected. They also shed light on the internal dynamics of the ex-slave community and recount an African church history.

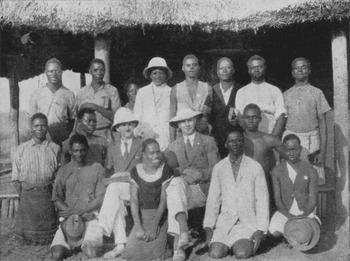

Finally, missionary photographs are an important source for this history. While the images were composed and taken within colonial relations of power, they were often still the subject of lengthy negotiation between the photographer and his or her subjects, providing the latter group with opportunities for self-presentation. Moreover, the photographers could never control the contingent in their images.Footnote 13 Beyond their primary intent, photos include useful contextual data on comportment, dress, and architecture, all key markers of respectability.

Missions and new elites

The experience of returnees to Belgian Congo differed from that of the West African re-captives in several ways. Although the Congolese placed a premium on literacy and learning, their education was more elementary than West African elites. None had attended formal mission schools or superior Christian colleges, and most were not bourgeoisie or even petite bourgeoisie. They did not become lawyers, doctors, or journalists or go into trade like the Saro-Yoruba returnees. They had little opportunity to take up self-improving leisure activities. Neither were they loyal to any particular empire having lived under both the Portuguese and Belgians, and having received an informal Christian education from British and North American missionaries.Footnote 14 Because their freedom came after racial boundaries had hardened in the age of scientific racism, they did not experience the embrace and subsequent betrayal by Europeans that so disillusioned other Creole elites.Footnote 15 The Congolese returnees relocated 1,000 miles into the African interior, equidistant between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, far removed from strong imperial connections and cosmopolitan influences. Amidst the insecurity of south-eastern Belgian Congo in the 1910s and 1920s, this more humble group of ex-slaves was reliant upon missionaries for patronage, protection, employment, and connection with the wider world. Yet their relationship with missionaries was intense and often fractious.

The Congolese returnees, working mostly as evangelists and pastors, considered themselves civilised and cultivated respectability to assert their status. Respectability is a highly mutable ideology that takes local forms, involving codes of conduct and physical markers that are continually renegotiated. It is usually asserted against some notional threatening ‘other’ who is variously defined as rough, backward, ignorant, inferior, and generally immoral. It is also often motivated by a desire for social mobility and public recognition. In his research on skilled artisans in Bristol, England in the 1990s, Tim Jenkins argues that achieving respectable status involves ‘a double movement’: first, ‘a separation from the mass of working class’, and secondly, ‘a search for external recognition of this separation’.Footnote 16 Jenkins contends that respectability entails ‘both the value of the person in his or her own eyes, and his value in the eyes of his society … Respectability like honour is both a personal and public matter.’Footnote 17

The Luba and Songye returnees cultivated respectability by embracing European and Luso-African material culture, manners, and mores. This Christian respectability also entailed the wholesale adoption of the evangelical missionary response to ‘paganism’. The ex-slaves asserted strict moral boundaries between themselves and those they viewed as uncivilised. They built separate villages or relocated to mission stations to create physical distance between themselves and their non-Christian neighbours who they fiercely denounced for their heathen practices. While respectability may have been, as John Iliffe has argued, a missionary strategy to tame some of the more violent African notions of honour, it took on a dynamic of its own amongst these progressively minded converts.Footnote 18 Reading their own experiences of slavery and redemption into the Scriptures, they gained a sense of dignity, seeing themselves as beneficiaries of God's providence and agents of a black Manifest Destiny to bring salvation to Africa. And, like the Khoi in nineteenth-century Cape about whom Elizabeth Elbourne has written so poignantly, those former Luba and Songye forced to participate in the slave trade also found expiation of guilt and the rhetoric of renewal in evangelical conversion narratives.Footnote 19 The new moral codes they adopted were what Elbourne describes as ‘a means of gaining self-respect, of reconstructing community, and of restoring honour lost by servitude’.Footnote 20

But, as Tom McCaskie has observed, pre-Christian values also influenced respectable identity. While returnee cultural norms were imbued with evangelical precepts and a European understanding of the ‘achieving individual’, ‘a successful Christian was also required to manifest traditional, if modified, norms of attainment’ such as ‘the public display, enjoyment and conspicuous consumption of wealth’ and ‘the possession of a following of clients [and kin], conferring esteem, prestige, and weight in the community’.Footnote 21 The ex-slaves’ response to tradition was selective. They opposed traditional religious practices but engaged in local politics to enhance their reputations. Moreover, those who appeared to have most influence came from families with higher status in Luba and Songye society.

Closely related to their respectability was the former slaves’ commitment to a Christian modernity. The ex-slaves used the notion of being ‘modern’ as a distancing strategy to separate themselves from non-moderns and to claim membership in a new Christian community alongside missionaries.Footnote 22 Like ardent Christians across the globe and other aspirational African communities, these former slaves approached the ideological and institutional formations of modernity selectively. They took from modernity new tools for governing social arrangements while rejecting many of the values of cultural modernism. They valued literacy, schooling, biomedicine, bureaucratic forms of church government, urban organisation, and mechanical reproduction but shunned wage labour in order to retain their independence. They actively challenged social hierarchies based upon race but sought more limited modifications to those based upon kinship, which provided other sources of rank and hierarchy. Their evangelical Protestantism envisioned and enacted radical ruptures from the past but also harkened back to an imagined New Testament age in which providential signs and miraculous happenings were the stuff of daily life.

Hunt has written with great insight about African mission elites who worked with the Baptist Missionary Society at Yakusu in the Upper Congo region of Belgian Congo. These were teachers-, house girls-, and medical orderlies-cum-evangelists who ‘translated and debated’ new ideas and technologies introduced by missionaries, particularly biomedicine.Footnote 23 Many of these ‘middle-figures’ were redeemed slaves, who had a similar mediating role as the former slaves who returned to Katanga and exhibited similar ambivalences towards both their missionary patrons and non-Christian neighbours and kin.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, there were significant differences between the intermediaries who worked with the Baptist missionaries and those who worked with the CEM, the organisation the returnees mostly associated with in Katanga. The Baptist missionaries worked with surrogate children, who were ‘raised and bottle-fed in missionary homes from infancy’.Footnote 25 These ex-slave children, usually redeemed from caravans, were very different from the returnees to Katanga many of whom were middle-aged. The former slaves from Katanga were not as malleable as the Baptists’ young protégés. They returned with a strong sense of vocation and a reluctance to subordinate themselves to missionary schemes. Moreover, the Pentecostal faith missionaries of the CEM who pioneered much of South Katanga were very different from the Baptists. They initially had neither the resources nor the inclination to build substantial medical and educational infrastructures, and train African nurses and teachers. They were driven by a millennial fervour to evangelise and avoided building large mission stations so as not to slow the continuous proclamation of the Gospel. CEM stations neither resembled the ‘Little Englands’ in the rainforest created by the Baptists nor the vast mission towns, even ‘Kingdoms’, created by Catholic missions. Instead, a single missionary family was responsible for vast swathes of territory. Because they did not initially build mission schools and hospitals, and remained heavily dependent upon African evangelists, CEM missionaries developed an uneasy relationship with the former slaves.Footnote 26

Enslavement and return

Slavery persisted in Angola after the Portuguese Anti-Slave Trade Decree of 1836, stimulated by increasing European demand for ivory. Captives from the interior were compelled to carry tusks to the coast or were exchanged for ivory.Footnote 27 Subsequent demand for beeswax and then rubber perpetuated the slave trade into the twentieth century, pushing the slaving frontier further into the interior.Footnote 28 The former slaves who are the subject of this article were taken captive in the thousands from Lunda, Luba, and Songye territories in what became Belgian Congo and transported by the Ovimbundu to the slave markets in Bié and Benguela in Angola during the 1870s–1900s.Footnote 29 Most were seized in countless small incidents of local warfare, kidnapping, personal betrayal, and financial and political crises that accompanied the collapse of the former kingdoms of the Eastern Savannah and the establishment of new predatory polities led by slavers and trading barons such as Tippu Tip and Msiri.Footnote 30 Whatever their origin, many of the captives ended up in the hands of the Ovimbundu in exchange for cloth, beads, salt, powder, and guns.Footnote 31 Slave narratives recount a downward spiral of misery and horror once people were removed from their own societies and placed on the trail to Angola.Footnote 32 Not all the slaves were exported; Biéns retained many for domestic purposes.Footnote 33

As many as half of all Ovimbundu owned slaves. Slavery in nineteenth-century Bié encompassed a variety of conditions and degrees of oppression. Slaves were put to work in households, plantations, and factories. Those who were of a hardy disposition hunted and traded on behalf of their masters.Footnote 34 Given their dominant position in long-distance exchanges between the Benguela Coast and Central Africa, trade offered the Ovimbundu great opportunities for advancement.Footnote 35 Caravans, in particular, were engines of social mobility in which slaves who ran successful caravan operations on behalf of their masters could win social esteem or even freedom.Footnote 36

Not all of the returnees discussed here were enslaved. Two of the major figures, Shalumbo and Kaluwasi, had prospered though Ovimbundu trade, joining caravans that passed through Katanga, eventually settling in Bié. Given their experience of travel and adventure, it is not surprising that these two men led parties of former slaves returning home. Indeed, oral sources describe Shalumbo as the ‘captain’ who organised the return of all of the Luba groups with a military precision.Footnote 37

Existing sources do not allow for an accurate survey of the modalities and geography of slave conversion in Central Angola (Fig. 1). But many of the returnees appear to have lived in the vicinity of Protestant missions: the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), Canadian Congregationalists, and the Plymouth Brethren. These missions dominated central Angola and were situated on the trade route to Katanga. The American Board arrived in 1880 followed by the Canadian Congregationalists in 1886.Footnote 38 The Plymouth Brethren work in Angola commenced in 1889. Other Brethren missionaries founded a chain of stations stretching eastwards from Angola into Katanga, which would eventually provide assistance for ex-slaves journeying homeward.Footnote 39

Fig. 1. Protestant missions in the slaving corridor of West Central Africa, early twentieth century.

A testimony by a former slave, Shambelo, published in the missionary periodical CEMR in 1924 recounts how he was purchased by Chief Kanyundu – ‘a very powerful Biean’ from Chissamba who was healed of bronchitis by the charismatic Canadian Congregationalist missionary, Walter Currie. Shambelo's testimony, which aligns remarkably well with Currie's diary, tells how Chief Kanyundu converted, rejected polygamy, freed over one hundred domestic slaves, and rebuilt his village in linear fashion according to the Canadian missionary's designs.Footnote 40 When in 1910, the new Portuguese Republic made effective a law passed by the monarchy forbidding slavery, other former slaves relocated close to mission stations for protection and patronage.Footnote 41

Three main groups departed from Angola for Belgian Congo, followed by smaller parties. The process of return began in 1910 when Kayek Changand, a Christianised Lunda slave and caravan leader, met John and Helen Springer, American Missionaries of the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) at Kalulua on the frontier between the two colonies and Northern Rhodesia. Convinced of the missionaries’ commitment to the Lunda, Kayek promised to return with a party to help them establish a mission. Although freed by the Portuguese decree of 1910, he still considered himself honour-bound to his master and first returned to Angola to ransom himself with the profits of his trade.Footnote 42 The MEC station at Kapanga, founded in 1912, became the staging post for two Luba parties led by Kaluwasi and Shalumbo.Footnote 43 Kaluwasi's group travelled furthest, moving 1,000 miles to northern Luba territory to help the Springers establish a mission station at Kabongo.Footnote 44 Shalumbo's party moved to the new Mwanza station of the CEM pioneered by William Burton and Jimmy Salter.Footnote 45 Both parties arrived in Katanga in 1916. The numbers are hazy but there were certainly in excess of 300 Lunda, Songye, and Luba returnees. Once in Belgian Congo, there were also apparently ‘Bakaonde, Basanga, Bapemba and Bachokwe’ dispatched in different directions by a European official.Footnote 46 A similar process of return occurred in the Kasai Province of Belgian Congo.Footnote 47

There were strong material reasons for the ex-slaves’ return to Belgian Congo. The massive slave population in Bié became unsustainable as tree cover diminished and fragile soils eroded.Footnote 48 In the short term, Ovimbundu livelihoods were undermined by the imposition of hut tax, state restrictions on hunting, the curtailment of the slave trade by the Portuguese and Belgians, the falling price of rubber, and a settler land-grab. Conditions worsened with a series of natural disasters ending with a severe drought in 1914, which pushed Ovimbundu from outlaying areas into Bié in search of food and work. Amid these hardships, former Ovimbundu traders turned to peasant farming and labour migrancy, leaving few opportunities for ex-slaves.Footnote 49

In addition to these push factors, ex-slaves were also drawn home by a missionary imperative. Stories of slavery and redemption, coupled with the notion of providence, provided returnees with a theological rationale for their past while enabling them to envision an alternative future. Of these narratives, the story of the Hebrew Exodus was paradigmatic. According to a latter-day missionary source, a North American missionary prompted the idea of return when he recounted to a group of Congolese slaves the story of how God had ‘opened the way for the children of Israel’.Footnote 50 The Exodus narrative was appropriated by the returnees and sustained them as they journeyed home and faced hunger, illness, random violence, and the corruption of colonial officials. Once home, the story of Israel provided the returnees with a vocabulary to reimagine their identity in a new and often hostile environment. Describing his opening encounters with Kayek, the MEC missionary John Springer wrote: ‘An interesting item in Kayek's testimony in prayer meetings was how he had felt the similarity between himself and Joseph, who had been sold into slavery in a far country, and that God had designed Joseph to be the deliverer of his people, so he, Kayek, had felt that he had been taken into slavery that he might bring back spiritual deliverance to the Alunda.’Footnote 51 Springer's account, which is corroborated by Kayek's grandson, noted that henceforth, Kayek saw himself and his children – appropriately named Sarah, Rachel, Esther, and Moses – as the nucleus of a new Christianised Lunda.Footnote 52 In a similar manner, the section of Marcel's biography of Shalumbo, describing the former slaver's return home, is prefaced with: ‘The fulfilment of Scripture: “The Israelites set out from Ramses on the fifteenth day of the first month, the day after the Passover” Numbers 33.3.’Footnote 53

African missionaries

The former slaves returned intent upon enlightening their former communities, who Shalumbo's Congolese biographer described as living in ‘great darkness’.Footnote 54 Like the Yoruba returnees from Sierra Leone to Nigeria, the Congolese ex-slaves would play a critical part in the Christianisation of the Lunda, Luba, and Songye.Footnote 55 Two sets of factors enhanced Congo returnees’ credibility. First, some still claimed ‘native’ status. Many of those captured as children were able to re-establish connection with kin left behind. And those who were the sons of traditional leaders were able to exploit the considerable local influence their relatives possessed. Secondly, as discussed below, the former slaves returned with literacy, new skills in construction and cultivation, and an understanding of some modern institutions that made them valued resources in their former communities. Unlike the freed slaves who comprised missionary-engineered Christian villages in East Africa, the Congolese returnees were not stigmatised for their servile past.Footnote 56

Before they left Angola, the returnees had acted as indigenous evangelists, a Brethren party led by Shalumbo having ‘a good effect on the district’ where they had gathered before departing. Like Kayek and Kaluwasi, they preached to those they encountered on the journey home.Footnote 57 Once back on native soil, the returnees shaped processes of Christianisation by influencing mission strategies and conducting their own evangelism. Having pioneered work at Kapanga among the Lunda, Kayek pioneered work at Mwajinga.Footnote 58 Similarly, Shalumbo persuaded William and Hettie Burton to trek several hundred miles into Songye territory in 1920 to commence work there.Footnote 59 Kaluwasi made a deep impression on Springer, who described him as one of the most earnest Christians he had ever met, a man crushed by his burden for his people.Footnote 60 It was Kaluwasi's vivid description of the northern Luba, who were as numerous as ‘trees of the forest’, that influenced Springer's somewhat irrational decision to found a station at Kabongo, hundreds of miles from the body of the American Methodist work amongst the Lunda.Footnote 61

The returnees launched a Luba Christian movement. Given the limitations of the American Methodist work and the relatively small amount of Luba territory worked by the Brethren, the story is mostly told in CEM sources. Like many missionary pioneers, Burton and Salter were initially overwhelmed. Along with the challenges of securing sustenance and shelter, and surviving periodic bouts of illness, there was also the work of furniture making, government correspondence, general mission business, and the training of new recruits.Footnote 62 They barely had time for evangelism and when they did, there was the added challenge of proselytising in their rudimentary command of the Luba language.Footnote 63 Hence, the arrival of the ex-slaves was timely. They built themselves a row of huts on Mwanza's mission hill and commenced evangelical work in surrounding villages. Sometimes they would reappear with ‘inquirers’, as in the case of the unnamed ex-slave who had visited his people ‘12 days north’ and returned with 34 villagers who built a temporary settlement for themselves and spent the rainy season learning at Mwanza.Footnote 64

No female returnees are named in missionary texts, but oral sources reveal their significance in the Mwanza community. Most male Luba returnees were accompanied by Ovimbundu wives because Luba women and children had been more easily assimilated into African communities in Bié. But those Luba women who did return were indispensable to the missionary Hettie Burton in her work among local women, helping her with language learning, offering counsel on custom, and teaching her the skills of midwifery.Footnote 65 One Luba woman returnee, Sala Kamone, recognised by her descendants in a CEM magic lantern slide shown to them by the author, was renowned for Bible teaching, visions, and healing.Footnote 66

William Burton eventually coordinated the work of the returnees, sending them out to live in villages and build local churches, and pushing the Christian frontier far ahead of the missionary frontier. Shalumbo pioneered the second major CEM station at Ngoimani, leaving the nucleus of a Christian community for white missionaries.Footnote 67 He later returned to Songye territory to pioneer work at Kipushya until his death in 1937. Other former slaves-turned-evangelists whose endeavours reached the pages of the CEMR were Shambelo, son of Chief Kabenga; Kangoi; Ngoloma, son of the mfumu (counsellor) at Mulenda; Shimoni Kibanza; Petelo; Shayaono; and Musoka.Footnote 68 These men pioneered stations that they left in missionary hands, occasionally converted local chiefs, and founded their own villages complete with schools and churches. The first published account of the CEM's work, Missionary Pioneering in the Congo Forests (1922), carries a photograph of Kangoi and Ngoloma with Burton's caption: ‘Two of our native overseers’. These men take practically the same place and responsibility with regard to the young native churches as the white missionaries.’Footnote 69

At times, however, African confidence and evangelistic endeavour irked missionaries. Ngoloma's influence within the Kikondja court alienated older counsellors. These traditional leaders persuaded the chief to invite Catholic missionaries as a counterbalance to Ngoloma's influence, thus impeding the work of the first CEM missionaries in the area.Footnote 70 In spite of his hagiographic representations of African evangelists, Burton confessed in private correspondence that he found Ngoloma a ‘difficult customer’, too ‘independent’.Footnote 71

Like the Yoruba evangelists who are the subject of Peel's study, these ex-slaves actively confronted traditional ‘religious authorities and the social order they represented’, sometimes provoking violent reactions.Footnote 72 Shimoni resisted the powerful paramount chief at Kabongo's desire to marry his daughter, insisting instead on Christian monogamy.Footnote 73 Shalumbo filled in a pit used by a vidye (spirit medium) located next to his village chapel. He also opposed the dances of the Bambudye association that initiated political candidates into the rules and secrets of royal chieftaincy.Footnote 74 Central to this confrontation, as in the Yoruba case, was the ex-slaves’ role as agents of ‘disenchantment’.Footnote 75 Shalumbo debated with diviners the existence of local spirits, and argued that nkishi (wooden memory figure embodying spirits) were no more than ‘lifeless forms’. He also publicly burnt the charms of new converts.Footnote 76 When Shalumbo's protégée, Shayaono, discovered an eland horn charm outside his hut one morning, he paraded it in the centre of the village as an object of ridicule.Footnote 77 Such instances of repudiation were constitutive of African Christian modernity.

Respectability and modernity

The returnees’ respectability comprised a cluster of values that were sometimes at odds with each other. Inward concern with moral reformation stood in conflict with an outward one to assert status though display and consumption. Conflict arose when it seemed that the returnees were too respectable to be the humble Christian servants the missionaries desired. By the year of their release in 1910, the ex-slaves had adopted Western styles of dress, deportment, and architecture, and had embraced literacy and Western marriage patterns. Other changes were inward. Like the Euro-American middling sorts who formed the bulk of missionary recruits, the former slaves regarded sobriety, industry, self-discipline, and chastity as key in their struggle against degradation. But unlike their white missionary forebears, they did not define themselves against a polluting underclass but against the pagan ‘other’. A letter penned by William Burton in 1917 outlines the parameters of the former slaves’ respectability. The letter was to his Brethren colleagues in Angola offering news of the former slaves’ arrival at Mwanza. From its style, the missive appears to be a verbatim transcription of the returnees’ account of their journey home with Burton's anti-Catholic annotations in brackets:

We thirty people have arrived here at Mwanza well. The Government official at Dilolo begged us to stay there, but we said, ‘No, we are God's people, and we desire to stay with the people of God.’ The Bulamatadi at Chimpuchi also asked us to remain. He said, ‘The children will die by the road, and also you have women’, but we answered, ‘No we wish to go.’ The spectacled man at Mulalango also tried to turn us back, but we went on. Also at Kikondja, when the official desired us to stay, we replied, ‘We wish to go to God's people at Mulongo.’ He told us that the missionary from Mulongo was away, and we should go to Kulu. We asked, ‘Is it to Mupe (the R. C. priest), who wears clothes to his feet and smokes a pipe?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Ah!’ we replied, ‘We don't want to go there; we want to go to God's real people.’ ‘Well,’ said the official, ‘go and sit at Mwanza with the white men and ladies there.’ We came here and are at Mwanza. We prayed on the road for God to lead us to the right people, and He has brought us to those who believe and pray, and we also speak and pray with the people … We sing our hymns together with the people … we refuse to go to our father and mother (about 10 days north from here and in an R. C. hotbed) for God is our Father. There they invoke fetishes and drink beer, but here we are by God's people.’Footnote 78

This letter showed the returnees’ determination to travel home, matched by a strong sense of God's providential care. It also demonstrates their commitment to low-church Protestantism and determination to assert a Christian respectability, expressed through creating spatial and moral boundaries between themselves and polluting others. The missive elides Catholics with traditionalists because of their consumption of tobacco and alcohol, and because their use of religious statues resembled pagan idolatry.

Like former native policemen and soldiers, and Christianised ouvriers (workers) brought from the west of the colony to construct railways in Katanga, ex-slaves had no wish to live under the authority of traditional chiefs in so-called ‘pagan’ villages. Although the returnees were motivated by a Protestant sectarianism, their desire for separation ran deeper. They exhibited a deep anxiety about the contaminating effects of the ‘uncivilised’ and chose to reside at mission stations or subsequently in their own Christian villages. In addition to repudiating ancestor religion, tobacco, and alcohol, Christian respectability entailed what David Goodhew has described for mid-twentieth-century South Africa as ‘a stress on economic independence, on orderliness, cleanliness and fidelity in sexual relations’.Footnote 79 Its basis was a monogamous Christian family that adhered to certain patterns of domesticity and consumption.

Photographs in missionary publications illustrate how the Christianised former slaves (and ex-slavers) displayed their respectability, and embodied the values Goodhew describes. In Burton's hagiography of Shalumbo, there is a photograph of CEM missionaries and evangelists who worked with him in the Songye area of Kipushya. Most of the evangelists wear simple utilitarian cotton shirts (Fig. 2). In the middle row are missionaries Johnstone and Mullan, attired in jackets, white trousers, and ties. Not to be upstaged, Shalumbo stands in the row behind wearing an immaculate white suit and pith helmet, a missionary in his own right. Above, there is a stereotypical photograph of Shalumbo sitting proudly with his Christian family (Fig. 3). Behind them is their home in which was found a ‘splendid four poster bed’ and ‘neat but simple furniture’ attesting to the virtues of monogamy as a route to respectability.Footnote 80 What is striking about the image is the size of Shalumbo's family. Much larger than the usual missionary image of evangelist and nuclear family, it suggests a pre-Christian concern to assert manliness through a capacity to produce, sustain, and defend a large household.Footnote 81

Fig. 2. White missionaries Johnstone and Mullan, in jackets, white trousers, and ties, are in the middle row surrounded by youthful evangelists in simple attire. Shalumbo, an ex-slaver and Christian convert, is in the row behind with a white suite and pith helmet, asserting his own credentials as a missionary. From W. F. P Burton, When God Changes a Man. A True Story of this Great Change in the Life of a Slave-Raider (London, 1929), 104–5.

Fig. 3. Shalumbo's family shown in this photo exceeds the missionary ideal of a nuclear family and, instead, reflects the local valuation of large and prosperous households. From Burton, When God Changes a Man, 104–5. (Courtesy of CAM)

Christian respectability was also performed. Writing contemporaneously, Springer's 1913 account illustrates the multifaceted nature of Kaluwasi's commission to Katanga:

Baluba Christians there in Bihé said, ‘You go back with Kayeka [sic] and see if any of our people are still alive and tell them the Good News of Salvation. We will take care of your wife and children while you are gone and we will pay a man to go with you to carry your box and chair.’ Kaluwasi protested; he could take but a few things and carry them himself and he could sit on the ground. ‘No’, they said, ‘we will not have it so. You go as our representative and we will not be put to shame. And you must have respectable clothes to wear, so we will send the man with you.’Footnote 82

The ‘steamer chair’ carried by Kaluwasi's Mbundu porter was commonly found in houses in Bié, and was intended for his use when preaching because Kaluwasi's people did not want him demeaned by sitting on the ground.Footnote 83 In a similar fashion, Shalumbo wore his boots as a mark of sophistication until he was humbled by a religious revival at Mwanza, after which he went barefoot like his fellow faithful.Footnote 84

While the returnees willingly collaborated with missionaries in the work of proselytism and civilisation, particularly in their former home areas, there were some locations they refused to visit. They also had expectations about the standard of living missionaries provided for them and strong opinions about what constituted orthodox Christianity. At Mwanza, the former slaves initially refused to work in the villages around Lake Kisale because of mosquitoes, preferring locations where the food was more plentiful and the people, sympathetic. One ex-slave incited his fellow evangelists at Mwanza to demand a better diet, more time for study, and less manual work.Footnote 85 Moreover, such was the strength of their prior formation as Brethren and American Board Christians that the ex-slaves divided along denominational lines once in Katanga. They resisted CEM's Pentecostalism, opposing divine healing, glossolalia, and exorcism because they suggested a loss of restraint.Footnote 86 These practices were only accepted after a revival at Mwanza in 1920 – the same experience that had led Shalumbo to renounce his boots.Footnote 87 Social hierarchies were levelled when the Holy Spirit fell upon all regardless of rank.

Important to missionaries were the former slaves’ skills. Burton wrote: ‘Some could cut fine planks on the saw pit. Others could build in brick. They had brought good seed with them, and understood the cultivation of rice, potatoes and other things which were quite unknown in Lubaland.’Footnote 88 The returnees played an important part in the building of mission infrastructure. Saul, one of Kayek's group, could make bricks, and Kaluwasi was a skilled mason who constructed two brick houses for the Springers before helping Burton build at Mwanza.Footnote 89 The ex-slaves also used their technical skills beyond mission stations. In Kikondja, Ngoloma influenced local leaders to recast settlements as ‘neat villages’ of ‘straight clean streets … cut parallel, and at right angles’ each hut equipped with ‘effective sanitary arrangements’.Footnote 90 Shalumbo's Christian village was constructed according to a similar design.Footnote 91 At Lukoshi and then Kabongo, the returnees constructed ‘mission colonies’,Footnote 92 replacing ‘disreputable grass huts’ with a grid of well-spaced rectangular dwellings.Footnote 93 While the Belgian colonial state sought to reverse the earlier missionary strategy of founding Christian villages because they undermined the authority of chiefs, the returnees actively built them.Footnote 94

Many of the former slaves were literate and, like Yakusu's Baptist evangelists in the Upper Congo, they understood the power of paper and literacy in the practice of colonial life.Footnote 95 They had returned with letters of introduction that ensured their safe passage and secured them sanctuary. A 1924 edition of the CEMR includes a photograph of Shambelo smartly attired in white trousers and a khaki jacket holding a Bible and a piece of paper. In the accompanying translation of his testimony of double redemption, he declared that his two most valued possessions were the document that granted him freedom from slavery and his Bible that declared him free from sin (Fig. 4).Footnote 96

Fig. 4. In a testimony contained in the Congo Evangelistic Mission Report of 1924, Shambelo, the former slave and son of a chief featured in this photograph, expounded the notion of double redemption, declaring that his two most valued possessions were the document that granted him freedom from slavery and his Bible that declared him free from sin. The Congo Evangelistic Mission Report, 3, Jan.–Mar. (1924). (Courtesy of CAM)

The ex-slaves arrived in Katanga when there was an enormous popular demand for literacy. Ngoloma enhanced his influence over Chief Kikondja by teaching him to read and write.Footnote 97 Some ex-slaves schooled by Brethren in Angola spoke English and made excellent language teachers for missionaries. Of the group that returned to Kabongo with Kaluwasi, seven men volunteered to establish schools.Footnote 98 The returnees were also well placed to participate in the diffusion of the Luba gospels, published in 1921.

Dislocation, Trauma, and Christian Independency

Alongside the providentialist master narrative of Christian expansion into which returnees and missionaries integrated their experiences, stories of dislocation and trauma existed. There were also clashes over notions of respectability, particularly with regard to women. The returnees’ dislocation was caused by several decades of captivity and re-socialisation in Bié. Their Christian identity formed through encounters with the Ovimbundu was as defining as their sense of being Lunda, Luba, or Songye. They returned singing Umbundu hymns and reading Umbundu scriptures. Their appearance had altered; they wore different sandals, used different weaving and spear heads, and, of course, they sat upon steamer chairs.Footnote 99 Not all former Congolese slaves from Bié returned to Katanga.Footnote 100 Marcel's account of the origins of the Songye church stresses Shalumbo's sacrifice and faith in contrast to those who refused to accompany him. On hearing of ‘the way of life of the Basongye; their food, their marriage customs and many other different customs’, Shalumbo's children responded: ‘WE ARE NOT GOING TO THOSE HEATHEN PEOPLE WHO DON'T EVEN KEEP CATTLE!’ Even Shalumbo needed reassurance from missionaries that he would not ‘fall into heathen customs and the worship of spirits’.Footnote 101

In the 1910s, Luba and Songye territories were still marginal to the Belgian colonial state and without a Christian presence. To missionaries and returnees alike, they appeared to be particularly forbidding places. Springer who pioneered the Luba work used some of the choicest missionary terms to emphasise the challenge that lay before him: ‘I do not recall ever before having such a sense of being surrounded by a vast, odoriferous swamp of rank, sensuous, sensual and rampant heathenism.’Footnote 102 Wesley Miller, who was the first permanent Methodist missionary to be based at Kabongo, wrote: ‘Mr Bellemans [the local district commissioner] tells me that while he could not obtain positive proof, he is certain that the inhabitants of Kabongo are cannibals. We are in the heart of the largest cannibal area in this part of Africa. One good day's journey from here cannibalism is practiced openly. One is likely to find human hands and feet in any house one may choose to enter.’Footnote 103 Like most missionary accounts of cannibal practices, Miller's accusations were based upon hearsay. But while missionaries to Congo and elsewhere derived their ideas of cannibalism from classic mission and ethnographic writings, their impressions were bolstered by African Christian ex-slaves who were seeking to assert moral boundaries between themselves and the threatening ‘other’. Many of the returnees at Kabongo refused to be located in so-called cannibal villages.Footnote 104

Like his missionary colleagues, Miller found the returnees ‘uppity’, and did not view them with the same favour as homegrown ‘mission boys’. He had little appreciation of Kaluwasi's pioneering work,Footnote 105 which by 1918 had taken its toll on the evangelist's health.Footnote 106 The following year, Miller vented frustrations in a letter to Springer: ‘the Angola folks are a worthless crew. I have seen very little evidence of Christian devotion in them such as I have seen in native teachers of other missions.’ By this stage, one former slave-turned-evangelist was in prison and Saul had deserted his post to follow his wife Vita, who subsequently left him for a white man.Footnote 107 Saul eventually ended up in Mwanza where he was joined by Kaluwasi. The latter was now described by Burton as in a ‘thoroughly back-slidden condition’. Both were banned from speaking in meetings. As in the case of Miller's diagnosis of Saul's spiritual condition, Burton attributed a good many of Kaluwasi's problems to his ‘unchristian wife’ and her ‘foul heathen practices’.Footnote 108

The Euro-American missionaries working in south-east Belgian Congo held a firm set of beliefs about what constituted appropriate female behaviour. The home was the ‘cornerstone’ of evangelical strategy and within it the Christian woman was to practice devout domesticity and wifely submission to her husband. She was to make sacrifices in the socialising of her children and the support of her husband's evangelistic work.Footnote 109 These notions of respectability clashed views held by with some returnee wives who considered themselves too sophisticated to be in upcountry Congo at all. Missionaries often used the figure of the degraded African woman to justify their civilising mission, but the Ovimbundu wives of the returnees were certainly not degraded and did have real grievances. In his first encounter with Springer at Lukoshi in 1913, Kaluwasi requested presents for his wife in Angola so that he might dissuade her of the view that Katanga was no more than ‘veldt and savages’.Footnote 110 The Ovimbundu women, some of whom may have acquired considerable wealth in Angola, had sacrificed the most in leaving the comforts of home and kin in Bié, and felt poorly treated.Footnote 111

Burton and his colleagues also believed that the ex-slaves carried in their hearts ‘a secret nameless grudge’ which manifested itself in ‘smouldering bitterness and mistrust’.Footnote 112 Hettie Burton, who worked intimately with widows, orphans, and women in flight, interpreted the grudge as the ‘scars of former days’, the effects of ‘devilish cruelty’ from slavers:

One dare not walk up to them too abruptly, lest one see that look of supreme terror come over their faces again. We tried to laugh one old lady out of it, but big tears filled her eyes as she said, ‘If you had been beaten in the face as we have, flung to the ground, stamped on, if you had seen your companions’ throats cut or spears forced through their bodies, or heard them shriek and plead as they were roasted alive, or had wooden spikes driven into their brains, you too would wince when someone approached you too abruptly.’Footnote 113

Another missionary, William Burton, described being on the receiving end of a ‘perpetual grievance’.Footnote 114 Similarly, American Methodist missionary Wesley Miller wrote of Kaluwasi that he ‘seemed to have a grievance against someone’ and ‘was constantly trying to stir up the Christian people’.Footnote 115

Such tensions were similar to those between missionaries and African Christians elsewhere. In the pioneering stage of missionary work, evangelists had autonomy from overstretched and linguistically-challenged missionaries. Struggles often commenced on the arrival of a second generation of European Christian workers, who limited the speech and regulated the actions of African pioneers in the name of orthodoxy. Racism and paternalism intensified the conflict as missionaries refused to view the returnees as they viewed themselves – as civilised. At times, affronted African Christians, fatigued with being patronised and prevented from rising through the hierarchy of colonial society, broke away to form ‘independent’ or ‘prophetic’ movements.Footnote 116

In this area, the rival movement was Watch Tower, popularly known as Kitawala. This millennial movement was widespread between the two world wars in Nyasaland, Southern and Northern Rhodesia, and Belgian Congo. It came from the American Jehovah's Witnesses but moved a good distance from the teachings of its founder, Charles Russell, as it evolved in Central Africa. Probably the largest independent association of Africans prior to African nationalism, it attracted a good deal of commentary from colonial officials and missionaries, and subsequently from scholars.Footnote 117Kitawala was a wide-ranging and multifaceted movement, which took on different forms and significance in different contexts.Footnote 118 Its teachings were first introduced into Belgian Congo in 1925 by the renowned figure Tomo Nyirenda, also known as Mwana Lesa –the Son of God. Under his influence, the movement took a militant anti-colonial form, though it was also known for drowning Africans accused of witchcraft. Nyirenda was subsequently arrested and executed. According to John Higginson, the Congolese movement then took two different trajectories. The first was a quietest ideology of separation from industrial employment. Banapoleoni, the second more radical strand, led by Mumbwa Napoleon Jacob, moved northwards from Elisabethville into Luba territory, as the mining industry expanded to meet growing wartime demands. It encouraged workers to protest against poor employment conditions, and rural dwellers to protest against head taxes and government appointed chiefs.Footnote 119 It precipitated a short-lived millennial revolt at the tin mine at Manono which begun on 18 November 1941 when adepts stormed the district administration and tore down the Belgian flag.Footnote 120

The movement had a strong presence on the mines at Mwanza where in late November, a protest resembling that at Manono occurred. Watch Tower songs were sung and crowds threatened European officials.Footnote 121 Six leading CEM evangelists were arrested following the Manono uprising. The homes of CEM adherents were raided and their Bible notes and other religious literature were taken away for translation and scrutiny.Footnote 122 It would seem that the evangelists’ arrest was more a result of state paranoia than their sympathy for the Kitawala.Footnote 123 The black church leaders were merely the intended recipients of a letter describing events at Manono. Once Burton intervened, his evangelists were freed.Footnote 124

However, the colonial state had good reason to be suspicious of the CEM's links with Kitawala and there was doubtless osmosis between the movements at a local level. Both movements placed a strong emphasis upon possession by the Holy Spirit, had strong millennial theologies, stressed the importance of baptism by immersion, and encouraged members to sing militant songs about God vanquishing their enemies. Furthermore, both movements stressed literacy and personal engagement with the Scriptures. The CEM had been active in the dissemination of the Luba Gospels following their publication in 1921 and Kitawala adepts made good use of the prolific literature commentaries and tracts produced by the United States-based Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society. Both CEM and Watch Tower publications carried vivid illustrations of damnation for sinners and the arrival of the millennial dawn.Footnote 125

Emerging some three decades after the ex-slaves had returned, Kitawala presented CEM adherents with new opportunities. While none of the homegrown CEM evangelists joined the movement, it appealed to some ex-slaves. Of the three who fully committed themselves to the movement, two do not figure at all in missionary sources and perhaps held low rank within the hierarchy of former slaves. The other, Shayaono, was noteworthy for his evangelistic zeal but also for his outspoken criticism of missionaries who did not meet his standards of propriety and industry.Footnote 126 Former slaves, aggrieved by missionary patrons or irked by low status, made an easy transition from one movement the other. Kitawala adherents retained teachings on the Holy Spirit, the millennium, and an emphasis upon literacy but gained membership in an autonomous African movement and embraced a host of subversive doctrines that asserted equality between black and white. As one seasoned American Methodist observed, Watch Tower provided alternative doctrines by which to judge missionary Christianity.Footnote 127

Other former slaves stayed in the mission churches but chose to supplement their status by claiming rank in traditional society. In Kabongo, where relations with missionary Wesley Miller were particularly fraught, one former slave immersed himself in local politics and was imprisoned for ‘meddling’ and burning down ten villages.Footnote 128 Others were more successful in combining different types of status. Kayek used his position as a Lunda aristocrat (kazemb) to improve the standing of the American Methodist Mission at Likoshi, which was in the vicinity of King Mwata Yamvo's court.Footnote 129 Having become too influential at the Kikondja Court, Ngoloma retired to his village, working as an evangelist and counsellor (mfumu) at the same time.Footnote 130 Kaluwasi married two additional wives and severed relations with missionaries for a decade, only resuming a ministry loosely associated with the CEM when two of his three partners had passed away.Footnote 131 Shalumbo had no traditional status but such was his authority that he became the leader of his own Christian village from which he directed the writing of his biography that eventually became a canonical history establishing his role as founder of the Songye Church.Footnote 132

Conclusion

This article stretches scholarship on African Christianity in an important and new direction. Missionary literature and statistics highlight the immense scale of conversion in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; this account broadens our knowledge of the social and intellectual world of the agents who enabled those mass movements.Footnote 133 In essence, the returnees acted as cultural brokers. They were not elites like the clergymen, lawyers, journalists, and teachers who wrote texts and campaigned for varieties of West African cultural nationalism. Rather, in terms of social position, they were more akin to early African Christians in southern and East Africa. Nevertheless, they were enormously influential, encouraging their followers to adopt strands of Western modernity while simultaneously affirming aspects of African culture.Footnote 134 Crucial to the former slaves’ mediating role was their status as insiders and outsiders. On the latter, Peel writes: ‘[L]ike voluntary migrants, slaves were more religiously biddable than natives, both because they had lost many of the spiritual supports they had known at home and because, paradoxically, they were freer to make new religious choices.’ Freed slaves ‘had prestige in the eyes of their stay-at-home fellows from their knowledge of the wider world, particularly of the colonial domain, which they had acquired abroad’.Footnote 135 Possessing few social attachments on which to blame their misfortune, they were also open to new relationships beyond kinship, membership in associations and cults, and the patronage of traditional leaders. Such new relationships also left them well placed to engage with dimensions of the colonial political economy. As insiders, the returnees were embedded in their own societies as critics of local culture. When they opposed widely held beliefs and practices, ‘they did so knowingly’, as Peggy Brock has argued for indigenous evangelists, more broadly.Footnote 136

This article has also examined the conflicts generated by the former slaves’ social positions and experiences. While their dual perspective made them effective mediators of missionary Christianity, it also rendered them some of its earliest critics. Religious revival caused some ex-slaves to expand their notions of service and Christian brotherhood, but it was not enough to placate their Ovimbundu womenfolk who believed they deserved better. Neither was revival sufficient to overturn hierarchies of race maintained by missionaries. Most former slaves remained within mission Christianity but in villages far away from missionary surveillance. When Christian respectability did not provide the honour and dignity they desired, a few chose a radical millennial option that promised to erase the colonial order once and for all.