On the night of 26 September 1952, two Mau Mau assailants broke into the house of Headman Macuri in Aguthi Location, Nyeri District. They found their target, the headman, seated with his wife, winding down the evening. Because it was dark, one of the intruders brought out a flashlight and shone it on the headman, while the other shot him dead. But the two attackers did not attempt to harm the headman’s wife in any way.Footnote 1 In January 1953, a group of Mau Mau members broke into the house of Ganthon Gacigi and Rebekah Waceke in Mioro Sub-location, Fort Hall District. The group most likely wanted to force the couple, who were staunch Christian revivalists, to swear the Mau Mau oath. Gacigi was a carpenter and lay leader in the local Anglican Church, while Waceke was a trained teacher in the local government school. The two presumably rejected the oath and were subsequently strangled to death on the side of their bed. Their young son, however, was left unharmed.Footnote 2 That same year, Mau Mau fighters in Guama Sub-location, Embu District, broke into the house of an Anglican lay leader named Zakariah whom they accused of being a government informer. They hacked Zakariah to death, but they did not lay a finger on his wife and children.Footnote 3

These three attacks on a government employee, an oath-rejecting Christian couple, and a government informer were typical of Mau Mau killings: well-planned and carefully targeted operations. But there were some atypical though highly publicized incidents, such as the Lari attacks of March 1953 and raids on White settler farms, where Mau Mau assailants adopted a more indiscriminate approach.Footnote 4 This article seeks to explain how Mau Mau combatants selected and killed their civilian targets. Instead of microhistories of specific incidents, it attempts a synthesis of Mau Mau homicides that analyzes the common targets, methods, and motives of assault, with a view to uncovering the underlying moral logic. Moral logic here refers to the ethical considerations that informed whom Mau Mau attackers killed, how, and why they did it.Footnote 5

To be sure, there were political and socioeconomic logics that also engendered Mau Mau homicides, but scholars have emphasized these and largely overlooked the moral logic of Mau Mau violence.Footnote 6 The only exception has been scholars of Kikuyu moral economy who have analyzed the social controls that restrained violence on both sides of the conflict.Footnote 7 But because moral economy scholars have striven to show the continuities of nineteenth-century Kikuyu moral debates within Mau Mau, they have paid insufficient attention to how Mau Mau members debated and reimagined traditional ethics of violence. The central argument in this study is that Mau Mau members shared a moral logic that shaped the targets, methods, and motives of their killing campaign. Even though the Mau Mau movement was highly decentralized, the moral logic of killing cut across guerrilla units that operated in the various battlefronts. It was partly based on traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence, which were widely held and traceable to the late nineteenth century. Yet this moral logic was also born out of novel, albeit contested, ethical convictions that developed in the context of an asymmetrical anticolonial war in 1950s-Kenya.

An investigation of this kind is only possible thanks to the recent discovery of a rare cache of captured Mau Mau documents that government troops confiscated from guerrillas after they had killed or arrested them. Handwritten in Kikuyu or Kiswahili, the captured documents were translated into English and then disseminated as typescripts among intelligence officials. These documents, of which only the English translations have survived, were a mixture of journals, notebooks, diaries, letters, ledgers, and songbooks. They contained section-level records of oaths, prayers, prophecies, songs, dreams, animal sacrifices, burial rites, nicknames, promotions, chores, camp rules, disciplinary hearings, punishments, purchases, monetary and non-monetary contributions, battle histories, casualty figures, and records of homicide, plunder, and sabotage operations.Footnote 8

The British National Archives made this treasure trove of documents available starting in 2006 and 2007, but scholars have scarcely utilized it until now.Footnote 9 The captured documents allow this article to tell the important story of Mau Mau homicides from the perspective of the movement’s members and with unprecedented detail. The article uncovers biographical information about Mau Mau’s civilian enemies, including names, ages, sexes, occupations, and home sub-locations. It also illuminates the perceived offenses that civilians committed against Mau Mau, the motives of Mau Mau assailants, and the internal conflicts that arose regarding the killings of some civilians. This study begins with a brief discussion of the origins of Mau Mau. It then analyzes the most common civilian targets of Mau Mau killings and the ethical and military considerations that surrounded these homicides. Ultimately, the study demonstrates that the moral logic of Mau Mau killings was firmly rooted in a dialectical tension between longstanding Kikuyu ethics of violence and the harsh realities of waging an asymmetrical anticolonial war. It further shows that Mau Mau debates over who to kill formed part of a larger process of sacralization, whereby members of the movement reimagined what they deemed sacred, moral, and just measures for conducting the war.Footnote 10

Making Mau Mau

The Mau Mau movement began in the late 1940s among migrant Kikuyu farmworkers in Rift Valley Province.Footnote 11 These farmworkers, colloquially known as squatters, were resident laborers on European settler farms. By the end of the Second World War, many squatters had become disillusioned with the terms of their employment. Unlike the early years of European settlement in Kenya, when being a squatter was characterized by minimal labor requirements (ninety days per year) and unrestricted access to farming and grazing land, the interwar period witnessed White settlers place increasing demands and restrictions on their squatters. As settlers acquired more capital, they sought to expand and diversify their agricultural activities. This change meant putting more land into productive use and thus limiting how much land and free time was available to squatters.

By 1946, settlers had tripled the labor obligations of squatters to 270 days per year. Settlers further compelled squatters to slash their large herds of livestock (sometimes several hundred strong) to five per household, and they reduced squatter acreage from up to six acres per family to less than two. Unsurprisingly, many squatters refused to sign new labor contracts under these restrictive terms, so settlers began to evict them after the war. Between 1946 and 1952, the authorities forcibly evicted more than 100,000 Kikuyu squatters from the Rift Valley and sent them back “home” to the so-called Native Reserves in Central Province.

Upon their arrival in the reserves, squatters quickly discovered that they had jumped out of the frying pan into the fire. Due to natural population growth and European alienation of African land, the Kikuyu districts, especially Kiambu, were so overcrowded that there was hardly any room left to accommodate the new arrivals. Squatters who had hoped to stake a claim on land that their parents or grandparents left behind when they moved to the Rift Valley were soon disabused of such hopes. By the late 1940s, land shortage had become so severe in the reserves that local chiefs and mbari (sub-clan) elders were adjudicating countless land disputes before the Native Tribunals.

Consequently, local leaders showed little patience for the squatters’ land claims that needed to be retraced over several decades. Furthermore, some chiefs and elders were themselves accused of carving out mbari land and thereby dispossessing their neighbors, which made them targets of attack when Mau Mau killings began in mid-1952. Finding themselves landless and without relatives who were willing or able to take them in, some squatters slept rough in the reserves, while others sought refuge in the urban environs of Nairobi. But poor and inadequate housing for Africans, a prohibitive cost of living, extreme unemployment, suppressed wages, and high crime rates meant that the city offered no respite either.

Mau Mau thus appealed to different marginalized groups who shared common grievances against White settlers and the colonial authorities. It began as a protest movement among squatters who opposed new labor contracts and their subsequent evictions from the Rift Valley. Large numbers of squatters joined Mau Mau by swearing an oath and paying the membership fee. After leaving the so-called White Highlands, squatters spread the message and methods of Mau Mau wherever they went. Between 1948 and 1952, despite a government ban on Mau Mau in August 1950, the oathing campaign expanded to the landless and land poor inhabitants of Central Province and the large numbers of unemployed and underemployed residents of Nairobi.

All these groups saw in Mau Mau’s plan of organized violence their last hope for a better future. This expectation was captured in the movement’s military objectives: ithaka na wĩathi, land and moral agency. Mau Mau members hoped that organized violence would force the colonial authorities to reallocate land in the White Highlands to landless and land poor Africans and perhaps force White settlers to leave Kenya. In turn, they hoped that access to land would make them self-sufficient, opening the door to moral adulthood and full membership in society. As Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, the de facto leader of Mau Mau guerrillas on the Aberdare Range, lamented in a letter to Eliud Mathu in May 1954, Europeans have turned Kenya into a “country of boys,” a population of perpetual minors.Footnote 12 Kimathi was articulating a basic tenet of Kikuyu moral economy: a poor man could not become a full adult — that is, afford initiation fees, acquire land, pay bride price, raise a stable family, and attain elder status in his later years.Footnote 13 By 1952, this kind of moral agency lay beyond the reach of most Mau Mau members, so organized violence seemed to many as the only avenue left for achieving wĩathi.

Who deserves to die?

They called us terrorists, [but] did we really kill people for no reason? What kind of animals

would we be if we did that? We only killed those who refused to fight for wĩathi.

Joseph Waweru Thirwa (Mau Mau War veteran)Footnote 14

The Mau Mau War was one of the bloodiest chapters in the history of the British Empire after the Second World War. It was fought on at least four major battlefronts within the borders of colonial Kenya: the White Highlands adjoining Central and Rift Valley Provinces, the African reserves in Central Province, the forest reserves on Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Range, and the extra-provincial district cum city of Nairobi (see Figure 1, below). While there was a nominal Mau Mau central command known as Muhimu, the four battlefronts worked in loose coordination at best, and oftentimes in isolation. During a state of emergency that lasted from October 1952 to January 1960, government troops killed at least 11,503 Mau Mau suspects, mostly from the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru communities of Central Province.Footnote 15 The colonial authorities also detained hundreds of thousands without trial and forced more than a million inhabitants of Central Province to abandon their homes and move into government villages.Footnote 16 In contrast, Mau Mau combatants killed at least 167 government troops and 1,877 civilians.Footnote 17 Although shocking, these disparate casualty figures were not surprising given the asymmetrical nature of the war. Bands of ill-equipped and poorly trained Mau Mau guerrillas could not withstand the well-armed professional forces of the British Army, Royal Air Force, Kenya Regiment, King’s African Rifles, and Kenya Police. Mau Mau machetes and improvised firearms were no match for the government’s Lincoln and Harvard bombers, armored cars, artillery batteries, and Lanchester machine guns.Footnote 18

Figure 1. Map of colonial Kenya (1953–59) showing the major battlefronts in Central and Rift Valley Provinces during the Mau Mau War.

These disparities in military capacity largely explain why Mau Mau assailants killed eleven times more civilians than government troops. The former were unarmed or less armed than the latter and thus easier targets. Mau Mau killings of civilians were mostly premeditated, but some were spontaneous or even accidental. The civilian targets fell into three broad categories of Mau Mau opponents: government informers, employees, and loyalists. While it is commonplace within the Mau Mau historiography to lump these three groups together under the umbrella of loyalism, this study teases them out in order to highlight the moral stakes that surrounded the homicides in each group.Footnote 19 To be sure, these were fluid and compatible categories, but they were still sufficiently distinguishable to allow for systematic analysis.

Government informers

Mau Mau attackers targeted a wide variety of government informers, including spies, screeners, and crown witnesses, all of whom were Africans (many of them Kikuyu) who lived and worked in proximity to members of the movement. According to government intelligence reports, the first Mau Mau opponents to be killed were informers. On 15 May 1952, the corpses of two Africans were recovered from Nairobi’s Kirichwa River. At least one of the deceased had recently given information about Mau Mau to authorities in Nyeri, presumably his home district. And the civilian who discovered the two corpses and reported the matter to the police was himself killed shortly afterward.Footnote 20 Police investigations further revealed that between May and October 1952, Mau Mau assailants committed fifty-nine homicides, and at least twenty-three of the dead had been government informers.Footnote 21

The message from these early killings was clear: to give the authorities any information about Mau Mau was a capital offense in the eyes of a movement that thrived in secrecy. This warning was taken seriously in the Kikuyu-dominated parts of the colony. In April 1952, Ian Henderson, the assistant superintendent of police in Nyeri, admitted that finding witnesses to testify in the ongoing Mau Mau oathing cases was proving so difficult that officers had resorted to unscrupulous methods. “It is becoming necessary,” he confessed in his monthly intelligence report, “to deceive potential witnesses then suddenly hoist them in the witness box unprepared. This produces a timid and hesitating witness but the evidence in addition.”Footnote 22 By September 1952, despite these desperate measures, over 100 cases against Mau Mau oath administrators and participants had been dropped due to witnesses recanting their statements or failing to appear in court.Footnote 23

When the Nairobi municipal official Tom Mbotela was hacked to death on the evening of 26 November 1952, his body lay on the side of a busy road next to the bustling Burma Market for nearly twelve hours. Hundreds of pedestrians walked past the corpse, but no one dared to report the homicide to the police. It was not until the following morning that a White police officer who was driving through Shauri Moyo discovered the body.Footnote 24 In his official tribute to loyalists who resisted Mau Mau, the longtime colonial official Sidney Fazan characterized this failure to report Mbotela’s killing as a “sinister feature” of the incident.Footnote 25 But it was simply another example of Mau Mau’s success at withholding information from the government by targeting and intimidating informers. This silencing campaign continued well into the emergency. When General Sir George Erskine announced in April 1954 the start of the government’s Operation Anvil in Nairobi, he lamented the lack of information that had hindered the police from solving most Mau Mau homicides from the preceding fifteen months of the emergency.Footnote 26

Significantly, Mau Mau members themselves documented the deliberate targeting of government informers. Corporal Karari’s section, which operated in Nyeri, kept the best available records of a Mau Mau unit’s killing campaign. In captured documents that covered the period between December 1952 and October 1955, Karari chronicled the killings of ninety-six people whom his section had executed in Iriaini Location. He left no room for doubt as to why the section had committed these homicides. The list of executed males was titled, “The People Whom We Killed Because of Spying on Us,” while the list of females was headed, “Women Whom We Killed Because of Reporting Us.”Footnote 27

It is striking that Karari’s section dared to keep a record of their homicides. As the section’s chronicler, Karari would have known the obvious risk of self-incrimination that such records portended, yet he appears to have concluded that the risk was worth taking. He took the necessary precautions, though, because the section’s records were not discovered on him but at an unspecified location that the Special Branch code-named “HZS 1072.”Footnote 28 This location might have been one of the secret Mau Mau mailboxes in the district or guerrilla hideouts in the forest reserves on Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Range. By 1954, Mau Mau members had developed their own franking system to facilitate mail postage and delivery.Footnote 29 In Iriaini, where Karari’s section operated, there was a secret mailbox for each of the five constituent sub-locations: Thigingi, Kaguyu, Gatundu, Kairia, and Chehe. Overall, the captured documents show that for Mau Mau members, the need to chronicle their struggle far outweighed any fear of self-incrimination.Footnote 30

What is more, by keeping a meticulous record of their killings, Karari’s section demonstrated a strong belief in the justifiability of their actions. Karari detailed the name, sex, home district, location, and sub-location of each person they had killed. And for fifty-one of the ninety-six deceased, he included a description of the perceived offense that they had committed. Eighteen spies were killed for reporting oathing ceremonies and other Mau Mau activities that had taken place in Iriaini. Sixteen government scouts were executed for tracking the movements of guerrillas within the location and exposing the homesteads where they collected food and supplies. And five screeners were eliminated for helping government interrogators to identify Mau Mau supporters in the location. It is unclear why Karari failed to describe the perceived offenses of the remaining forty-five people. However, going by the titles he gave to the lists of executed males and females, the remaining forty-five might have been people about whom there was general suspicion of their being informers but inadequate intelligence on their anti-Mau Mau activities.

The list of executed males comprised eighty-one names, while the females’ list contained fifteen, which means that Karari’s section killed five times more males than females. The males’ list also included three minors aged twelve, thirteen, and fifteen. There was no mention of minors in the females’ list, but this silence should not be taken at face value. The extra effort to identify male minors and to create a separate, undifferentiated list for females indicates that the killings of boys, girls, and women were unusual. Indeed, traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence had long forbidden the killings of women and children.

When members of the British survey expedition for the proposed Mombasa-Victoria Railway arrived in southern Kikuyuland in March 1892, they learned of an “unwritten law” that provided safe passage for Kikuyu and Maasai women even when their men were at war.Footnote 31 Similarly, Italian Consolata missionaries, who began documenting Kikuyu proverbs in the early 1910s, recorded the adage, “Mũndũ mũka ndoragagwo,” a woman is never killed.Footnote 32 These prohibitions were doubtless a form of Kikuyu chivalry, yet they were also grounded in a patriarchal moral economy.Footnote 33 The productive capacity of Kikuyu men was “banked” in their wives and children.Footnote 34 A man’s wives and daughters cultivated the land, his sons herded the livestock, and the daughters upon marriage brought in additional stock in the form of bride price, which could be reinvested in more land and younger fecund wives. Killing women and children was thus a taboo because they were at once a store and measure of men’s wĩathi. Footnote 35

But the unique circumstances of the Mau Mau War forced members of the movement to rethink these traditional ethics of violence on two grounds. First, as the underdogs in an asymmetrical anticolonial war, Mau Mau guerrillas were forced to adopt offensive and defensive strategies that sometimes modified or transformed traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence. Second, the invention of mass oathing opened the door for Mau Mau fighters to debate the justifiability of killing women and children. Oathing was the ritual of initiation administered to new Mau Mau recruits. No one could join Mau Mau without swearing the secret, sacred oath of unity, which denounced British annexation of Kenya and called on everyone to join hands to reclaim the stolen lands.Footnote 36 Oathing sacralized the Mau Mau struggle by transforming commitment to the movement into a sacred communal duty. The oath bound individuals to a common cause, but it left them individually answerable to God, which fostered deep personal commitment to the movement.

Unlike traditional Kikuyu oaths, however, which only the elderly, propertied, male heads of households were eligible to swear, Mau Mau oaths were administered en masse. Anyone could swear the oath and join Mau Mau irrespective of their age, gender, or socioeconomic status.Footnote 37 Therefore, if women and children could be entrusted with the responsibility of swearing an oath, Mau Mau radicals argued, then they could equally be held accountable for opposing the movement. In other words, individual responsibility and accountability were two sides of the same coin. For Mau Mau moderates and conservatives, however, mass oathing was not a license to kill women and children. Individual responsibility and accountability extended only to adult males, not to females and minors. As the following discussion shows, Mau Mau combatants held these ethical and military considerations in tension throughout the conflict.

Of the three boys whom Karari’s section killed, the chronicler described the perceived offense that only one of them, Muriuki Ndango, had committed.Footnote 38 Ndango, a fifteen-year-old who lived in Kairia Sub-location, was killed because he reported to the authorities the death of Major General Mapiganyama in February 1954. Mapiganyama was the Mau Mau commander of the Hika Hika Battalion and a member of the Mount Kenya Committee, the supreme body in charge of military affairs on the Mount Kenya front. Under the chairmanship of General China, the committee comprised top military leaders from Nyeri, Embu, and Meru Districts. Select members of this larger body made up a leaner executive committee, and Mapiganyama was a member of it too.Footnote 39 His death thus dealt a major blow to the Mount Kenya forces who were still reeling from the capture of General China on 15 January 1954.

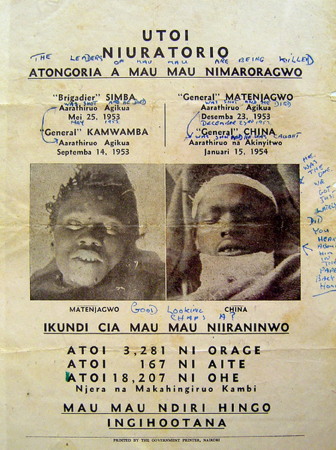

Mau Mau units strove to conceal news of their fatalities, especially the deaths of high-ranking officers, because they knew that the government would use such information in anti-Mau Mau propaganda.Footnote 40 Shortly after the capture of General China, for example, the government published leaflets in Kikuyu titled, “The Leaders of Mau Mau are Being Killed” (see Figure 2, below). The leaflets showed two unflattering headshots of General Matenjagwo and General China. Matenjagwo’s lifeless eyes were staring into the camera, with his mouth agape. He had been killed in December 1953, and the photograph on the leaflet appeared to be of his corpse. China’s headshot was placed alongside Matenjagwo’s. His chin, neck, and forehead were all bandaged; his eyes were shut; and his face grimaced in pain. The picture was probably taken on the day of China’s capture, following a fierce battle in Karatina where KAR soldiers shot him in the chin and throat.Footnote 41 Beneath the photographs of the two generals, the government listed Mau Mau’s total casualties until that point: 3,281 had died on the battlefield, 167 had been hanged, and 18,207 were in prison or detention.

Figure 2. A government anti-Mau Mau leaflet, 1954.

In view of this kind of government propaganda, the magnitude of Ndango’s perceived offense against Mau Mau becomes apparent. By reporting the death of a senior figure like Mapiganyama to the authorities, the teenager added fuel to the fire. Since Mapiganyama was killed in February 1954, it is more than likely that his death coincided with the publication of the government leaflets discussed above, which gloated over the deaths of Mau Mau leaders. Such government propaganda was intended to demoralize Mau Mau fighters and their supporters, so Ndango’s actions were seen as aiding the government’s counterinsurgency efforts.Footnote 42 For the Mount Kenya front, Mapiganyama could hardly have died at a worse time. The tide was turning against Mau Mau, and the streak of bad news was growing longer. The forest fighters would therefore have preferred to keep his death secret.

For Karari’s section, in particular, there was something even more unpardonable about Ndango’s actions. Not only was Mapiganyama a high-ranking officer, but he was also from Iriaini.Footnote 43 Given that Karari’s section operated in, and many of them were from, Iriaini, the death of the general must have been deeply felt.Footnote 44 They probably knew him personally and would have wanted to mourn him privately, without his death being used as government propaganda. This personal connection to Mapiganyama as well as the larger implications of reporting his death to the authorities likely sealed Ndango’s fate. And because the teenager was also from Iriaini, Karari’s section could not allow his actions to go unpunished as this would have emboldened other government informers in the location. In short, Karari’s section executed the fifteen-year-old Ndango because he leaked sensitive information that bore local and regional ramifications.

As for the fifteen women whom Karari’s section killed, the chronicler described the perceived offenses that only four of them had committed. A woman from Kaguyu Sub-location, whose name was listed simply as “Wife of Kagure,” appears to have been killed spontaneously for screaming at the sight of guerrillas. For the three other women, however, their killings were premeditated. Waguka Gakurumi, Muthoni Thinwa, and Wanjuku Njogu were all killed for being government informers, but Njogu’s case was unique because she was a double agent. She pretended to be a Mau Mau scout but actually worked as a government informer.

Mau Mau scouts in the reserves gathered useful intelligence for guerrillas, including the safest routes to use when they left their forest hideouts and visited the reserves. According to Karari’s description, Njogu would direct the movements of forest fighters and then give their locations to security forces who subsequently laid an ambush for the fighters. It is important to note that the average length of Karari’s fifty-one descriptions of perceived offenses was two lines of text. But at four lines, the description of Njogu’s offense was the longest and most detailed, suggesting that Karari’s section discussed and debated Njogu’s killing at length.Footnote 45

The discussion likely revolved around the egregious nature of Njogu’s treachery, which must have cost the lives of many guerrillas. The debate was probably among the section’s moral radicals, moderates, and conservatives on whether they should execute a female minor. Mau Mau scouts were usually school-aged children, some of whom had sworn the oath as early as age eight.Footnote 46 By April 1952, government intelligence showed that Mau Mau oathing had become so widespread at Kikuyu independent schools that some pupils were even administering oaths to their fellows. This open support for Mau Mau informed the government’s decision to shut down most of the independent schools in Central and Rift Valley Provinces during the first three months of the emergency.Footnote 47 It is thus reasonable to assume that as an experienced Mau Mau scout, Njogu was in her early to mid-teens. And given the taboos related to killing women and children, Karari’s detailed account of Njogu’s treachery likely reflected his section’s attempt to justify the retributive killing of a female minor.

Crucially, then, by keeping a meticulous record of their homicides, Karari’s section did not produce a mere catalog of violence. Their records functioned as a moral treatise that laid out why traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence needed to be reimagined while waging the Mau Mau War. Women and children were still a store and measure of wĩathi, but childhood and womanhood were no longer absolute defenses in the context of an asymmetrical anticolonial war. All active opponents of Mau Mau had to bear the responsibility of their actions, regardless of the reproductive capacity that they embodied. Documentation thus became an act of sacralization because it allowed Karari’s section to pen a new testament to the moral necessity of killing women and children. But as evidenced by the five-to-one ratio of male and female targets, Karari’s section judged the killings of women and children to be justifiable only on a limited scale. This position represented a compromise between the section’s moral radicals, on one hand, and moderates and conservatives, on the other.

There is also evidence that other Mau Mau units grappled with the same ethical questions that plagued Karari’s section. In July 1953, top Mau Mau leaders from the forest reserves on Mount Kenya and the Aberdare Range met near Karuthi Sub-location, Nyeri, to discuss the ethicality of killing women and children who opposed the movement. Coming four months after the Lari attacks, which had brought much negative publicity to Mau Mau due to the indiscriminate killings of seventy-four people in one night, many of them women and children, the meeting’s agenda sparked an intense debate among the leaders.Footnote 48 According to General China’s account of the meeting, the issue was so controversial that it had to be decided by a vote.Footnote 49 Of the fifteen leaders who were present, ten voted in favor of a motion to avoid killing women and children because such actions curtailed “the future growth of our population,” a position that embodied the vintage logic of Kikuyu moral economy.Footnote 50 But five leaders voted against the motion, insisting that all active opponents of Mau Mau had to be executed irrespective of their age or gender.

Even though scholars have overlooked the dissenting voices at the Karuthi meeting, the dissenters represented moral radicals who formed a significant minority within Mau Mau.Footnote 51 These radicals were the driving force behind the relatively small number of women and children whom Mau Mau attackers killed during the emergency. Such a conclusion is possible thanks to the comprehensive analysis of Mau Mau homicides that John Wilkinson published in July 1954. Wilkinson, a Presbyterian doctor who was based at Tumutumu Mission Hospital in Nyeri, compiled data from the autopsy reports of 1,024 executed Mau Mau opponents whose corpses had been examined at government and mission hospitals in Nairobi, Kiambu, Fort Hall, Nyeri, Embu, and Meru. Wilkinson was struck by the “preponderance of male victims”.Footnote 52 Since the start of the emergency, Mau Mau assailants had killed 926 African male civilians (90 percent) compared to 98 African female civilians (10 percent).Footnote 53

Wilkinson’s figures suggest that the radical decision to execute women and children who actively opposed Mau Mau had a counterbalance: guerrillas had to exercise great restraint while doing so. As a result, neither side of the debate got everything its way. Moral radicals could not obtain carte blanche to execute all women and children who opposed Mau Mau. They had to reserve death for what they perceived to be the most egregious offenses, such as Ndango’s espionage or Njogu’s treachery. Equally, moderates and conservatives could not prevent the killings of all women and children. Some transgressions were just too flagrant to go unpunished, and the military and political costs of showing unlimited clemency too high to ignore. In the moral logic of Mau Mau homicides, then, the tensions resulting from longstanding Kikuyu ethics of violence and the harsh realities of waging an asymmetrical anticolonial war were resolved through contestation and compromise.

Based on Karari’s records, government informers were a major target of Mau Mau killings. Mau Mau members bayed for their blood at every turn, always hunting for an “informer to be eaten”.Footnote 54 This deep contempt for government informers stemmed from the fact that they posed the greatest threat to Mau Mau’s military campaign. Withholding information from the authorities was one of the few weapons that the movement could wield against the government. Mau Mau machetes were no match for government machine guns, but a brick wall of silence could withstand most of the government’s bullets. Silence was the only force field capable of protecting a ragtag army of ill-equipped and poorly trained fighters.

Consequently, Mau Mau members swore to never reveal the secrets of their movement, and there was no such thing as harmless information.Footnote 55 This valorization of secrecy explains why Mau Mau attackers mutilated the bodies of some government informers. Three old men in Nyeri had their tongues cut out postmortem, while another man in Chogoria had his ears slashed off before he was executed.Footnote 56 It was not enough for Mau Mau attackers to kill these informers. A deterrent message had to be conveyed to the rest of the community, and it did not require much decoding: loose tongues and inquisitive ears brought severe repercussions.Footnote 57

In sum, as the emergency progressed, Mau Mau units found it increasingly necessary to eliminate government informers.Footnote 58 The targeting of informers was reported in Nairobi and virtually all the battlefront districts in Central and Rift Valley Provinces, including Nyeri, Fort Hall, Kiambu, Embu, Nanyuki, Nakuru, Naivasha, and Laikipia.Footnote 59 Mau Mau killed at least 1,877 civilians during the emergency, and approximately 640 of them were eliminated on suspicion of being government informers. If the rare killings of the relatives of suspected informers are added to this number at the rate of 10 to 15 percent, the total could rise to between 700 and 740.Footnote 60 This rough estimate is possible if one works backward from the official figures of fatalities that members of the provincial administration suffered during the conflict, which are discussed below. Yet it is important to note that some of those suspected of being government informers might have been executed as much for espionage as for their private feuds with Mau Mau members. As Daniel Branch has shown, this “privatization of violence” occurred on both sides of the conflict, and it was often related to the ongoing land disputes in Central Province.Footnote 61

Government employees

After government informers, government employees were the second main target of Mau Mau killings. They included government clerks, municipal officials, court officials, and, most frequently, members of the provincial administration. Fort Hall was the deadliest district for members of the provincial administration, and the only district where Mau Mau killed European administrators. Between October 1952 and December 1954, Mau Mau killed three European district officers (DOs), one assistant DO, one chief, nine headmen, twenty-eight tribal police, and 234 home guards.Footnote 62 By October 1956, across Central and Rift Valley Provinces, Mau Mau had executed at least three DOs, one assistant DO, eight chiefs, three chiefs’ retainers, seventeen headmen, sixty-three tribal police, and 667 home guards, which brought the total fatalities among members of the provincial administration to 762.Footnote 63 If the uncommon killings of the relatives of provincial administrators are added to this total at the rate of 10 to 15 percent, coupled with the infrequent homicides of agricultural assistants, forest guards, government clerks, and municipal officials, the final tally could rise to between 850 and 900 deceased, all of whom were Africans except for the three Fort Hall DOs.Footnote 64

While most Mau Mau killings were highly targeted, the executions of government employees were especially so, owing perhaps to their outspoken opposition to Mau Mau. On 7 October 1952, Chief Waruhiu Kung’u of Kiambu District was gunned down on Limuru Road while in the back seat of his car. The chief was on his way home from a land case in Gachie, Kiambu, where he had been appearing before the Central Native Tribunal as a witness for the defendant, a mbari that was accused of dispossessing another sub-clan of nearly 300 acres. There were two headmen riding with him, but neither the driver nor the headmen were shot or injured in the attack. The two Mau Mau gunmen were so determined to kill only Waruhiu that they walked up to his car, opened the rear door, confirmed that it was him, and then shot him four times.Footnote 65 Ironically, this extra effort to kill only Waruhiu is what solved the subsequent murder case. Thanks to the eye-witness accounts of Waruhiu’s driver and the two headmen, the gunmen were identified and arrested within one week of the attack. Government propaganda later boasted about the speedy arrest, prosecution, and hanging of Waruhiu’s killers, but the authorities conveniently ignored the highly targeted nature of the attack that had made a successful trial possible.Footnote 66

Similarly, in July 1953, a Mau Mau unit conducted the joint executions of Assistant District Officer Jerome Kihori and Chief James Kiiru of Fort Hall. In a well-planned ambush, the forest fighters placed a roadblock in Location 14 that forced the car carrying the two officials to come to a halt. As soon as it stopped, the fighters opened fire, killing Kihori, Kiiru, and several of their bodyguards. They then stripped all the dead men and carried off their clothes, guns, and money.Footnote 67

Whenever an initial execution plot failed, Mau Mau assailants demonstrated a steely determination to go back and finish the job. Chief Waruhiu had survived several attempts on his life before the fatal attack on 7 October.Footnote 68 The killing of Tom Mbotela in November 1952 came after several failed attempts.Footnote 69 That same month, Chiefs Eliud of Nyeri and Kigo of Fort Hall survived two separate execution attempts against each of them.Footnote 70 In late December 1952, Chief Hinga of Kiambu was shot in the mouth and wrist while walking near Limuru Town, but he survived the attack and was subsequently admitted to Kiambu Native Civil Hospital. Less than a week later, three gunmen gained access to his private hospital room and fatally shot him in the head and chest.Footnote 71 Headman William, also of Fort Hall, escaped unhurt when Mau Mau fighters first attacked his post in late April 1953. But his luck ran out on 2 May 1953, when guerrillas ambushed and killed him as he drove across a narrow bridge in Location 12.Footnote 72 All these examples highlight Mau Mau’s resolve to eliminate government employees despite initial failures in some instances.

Karari also documented his section’s killings of government employees. But when describing their perceived offenses, brevity became his preferred literary technique. Instead of relating their anti-Mau Mau activities with the same level of detail that he provided regarding executed informers, Karari simply stated these employees’ affiliations to different government agencies, without further information. It was as if their crimes were self-explanatory by virtue of them working for the authorities. Karari recorded that two men had been executed for being home guards, four others for being Criminal Investigation Department (CID) officers, and three others for being bodyguards to Chief Eliud, the chief of Iriaini. The brevity of these descriptions suggests that, unlike the cases involving women and children, there were no lengthy discussions or heated debates concerning the killings of government employees. Karari’s section judged government employees guilty of maintaining the status quo that had denied them wĩathi, so they had no qualms eliminating them.Footnote 73

Yet as with government informers, the lines between perceived political offenses and private feuds were blurred. One of the earlier unsuccessful attempts on Chief Waruhiu’s life took place in December 1950. The husband of a woman whom Waruhiu had fined for the illegal possession of traditional beer tried to spear the chief to death in the middle of the night. He fastened a spear onto a long wattle pole and then thrust it through the chief’s bedroom window in the hope of killing the old man in his sleep.Footnote 74 The aggrieved husband missed his mark, but it is highly likely that such people later joined Mau Mau and participated in attacks on government employees. For these guerrillas, executing a hated colonial chief or notorious home guard would have been both a political act and a form of personal retribution.Footnote 75

In the end, whether it was through detailed descriptions or succinct annotations, Karari’s section’s records spelled out the case for why they viewed their homicides as moral and just. The records demarcated the grounds on which the section had found men, women, and children deserving of death. And by including biographical information about their dead enemies, such as names, ages, sexes, and home sub-locations, the section seems to have been proclaiming that they had weighed the matter carefully before deciding to eliminate these opponents. It was as if they were declaring that nothing about the offender or the offense had been overlooked. Their meticulous records thus appear to have functioned as a medium of sacralization, an enduring proof of a thorough process, and a demonstration of what they perceived to be a just outcome.Footnote 76

Government loyalists

The third and final category of Mau Mau enemies was government loyalists. These were loyal supporters of the government who did not necessarily have a direct affiliation with the authorities. Both their loyalty to government and opposition to Mau Mau stemmed from a variety of factors, including political ideology, Christian faith, ethnic patriotism, class interests, racial privileges, and vocational necessity. They comprised European farmers, European missionaries, African mission teachers, African church leaders and congregants, and European, Asian, and African businessmen. Unlike government informers and employees, who actively opposed Mau Mau, government loyalists were usually passive opponents of the movement.

Some loyalists, however, such as the Fort Hall businessman Samuel Githu and members of the multiracial Christian Torchbearers Association in Nakuru, worked closely with the authorities in anti-Mau Mau offensives and even joined the provincial administration, which makes this category the most fluid of the three groups of Mau Mau opponents under consideration.Footnote 77 In the eyes of Mau Mau combatants, loyalists who partnered with the authorities in this manner were guilty of the same offenses as government employees. For most African loyalists, though, their perceived primary offense was refusing to swear the Mau Mau oath. In his memoir, Mau Mau from Within (1966), Karari Njama painted a vivid picture of what happened to anyone present at an oathing ceremony who rejected the oath. They were beaten into submission and would have been killed had they not changed their minds.Footnote 78

By mid-1953, any Kikuyu who had not yet sworn the Mau Mau oath was liable to punishment. Oathing had become so widespread that failure to swear the oath was assumed to be a personal choice rather than a lack of opportunity. Wanjiku Thuku, a former Mau Mau food collector in Kabati, Fort Hall, recalled that she and her compatriots had been very hostile to anyone in their community who refused to swear the oath, describing them as “fleas” that needed to be squashed.Footnote 79 When Kahinga Wachanga’s section raided Nyeri’s Gakindu Market in September 1953, they looted multiple shops but killed only one shopkeeper because he had rejected the oath from the start of the emergency.Footnote 80 The fact that Mau Mau members could keep track of those in their communities who had not yet sworn the secret oath of unity underscores the communal and sacralizing nature of the practice.

Ultimately, Mau Mau attackers killed any loyalists who refused to swear the oath. But unlike government informers and employees, who were typically attacked with firearms and pangas to ensure maximum fatalities, Mau Mau assailants usually strangled African loyalists to death.Footnote 81 This preference for strangulation was due to its controllability. Whereas pangas and firearms bolted the door to acquiescence when used, strangling ropes could be tightened or loosened to induce consent and thus avoid unnecessary deaths. Based on Wilkinson’s analysis of 1,024 Mau Mau homicides, about 11 percent of the movement’s African civilian opponents died from strangulation.Footnote 82 If this proportion is extrapolated to all 1,819 African civilians whom Mau Mau killed, the result is 200 fatalities due to strangulation.Footnote 83 This figure is the best estimate of civilians whom Mau Mau executed for refusing to swear the oath. If the rare killings of the children of oath-rejecters are added to this figure at the rate of 10 to 15 percent, the total could rise to between 220 and 230.Footnote 84

These killings were spontaneous in the sense that oath administrators could not predict which participants would reject the oath, but the decision to kill everyone who did so derived from Mau Mau’s moral logic. To countenance anyone who refused to swear the oath was to make room for a moral middle ground, that is, a neutral position in the conflict. Yet the moral logic of forced oathing was to ensure that such a middle ground did not exist. Everyone had to pick a side, and for many Mau Mau members, theirs was the side of truth and justice. As a former guerrilla on the Aberdare Range, Joseph Waweru Thirwa, recalled succinctly, “God was on our side”.Footnote 85 Echoing Jesus’s teaching that “whoever is not with me is against me,” Mau Mau members read indifference as synonymous with opposition.Footnote 86 They therefore saw the executions of oath-rejecters as justifiable on the grounds that neutrality only served to maintain the status quo that had hindered them from becoming moral adults.

Conscientious objectors, however, posed an even greater moral threat to Mau Mau than the neutrals. Rather than claim a middle ground, they climbed on a pedestal and staked out a moral high ground that towered over Mau Mau’s. This was unacceptable to Mau Mau members because it challenged their movement’s projection of moral superiority.Footnote 87 The leading conscientious objectors were Christian revivalists who regarded swearing the oath as “[denying] their faith,” owing to the ritual elements and solemn vows that were part of the practice.Footnote 88 According to the Anglican Provost of Nairobi, there would have been no Christian opposition to Mau Mau in Central Province had it not been for the revivalists. But these staunch revivalists made up only a small proportion of Christians in central Kenya during the emergency. Between October 1952 and March 1954, membership in the Anglican Church in Fort Hall shrank by more than 90 percent, from 12,000 to 1,000 members, leaving behind mostly the revivalists. A church that used to have a Sunday congregation of 200 parishioners was reduced to eight, and one that had 500 worshippers was whittled down to twenty. This drastic reduction in membership was largely due to church policies that required members to reject or publicly confess to swearing the oath, actions that would have invited deadly repercussions for congregants. Indeed, between October 1953 and March 1954, Mau Mau assailants executed six Anglican school teachers and eight church elders in Fort Hall for presumably rejecting the oath.Footnote 89

As for European and Asian loyalists, Mau Mau attackers killed them in cold blood or during bungled robberies where the objective was to acquire money, firearms, and other valuables.Footnote 90 However, European and Asian loyalists constituted only a small fraction of Mau Mau homicides. According to government statistics, the racial breakdown of civilians whom Mau Mau executed was 1,819 Africans (96.9 percent), thirty-two Europeans (1.7 percent), and twenty-six Asians (1.4 percent).Footnote 91 If these fifty-eight European and Asian loyalists are added to the number of African loyalists killed, the total fatalities could rise to between 278 and 288 loyalists.

Gloating over the low number of Mau Mau’s European casualties, Philip Goodhart, a conservative British politician, observed that more Europeans had died in traffic accidents within the city limits of Nairobi than had been executed in Mau Mau attacks throughout the colony.Footnote 92 Goodhart’s observation has become so commonplace within the Mau Mau historiography that it is often stated without a citation.Footnote 93 Even though it was intended as a gibe at Mau Mau, it is now taken as a “faithful reflection of the facts,” which seemingly requires no explanation or interrogation.Footnote 94

In reality, Goodhart’s comment betrayed the hypocrisy of White conservatives toward Mau Mau. Throughout most of the emergency, conservative European settlers in Kenya and their supporters in Britain were hysterical about the threat of Mau Mau. They called for a stern response from the authorities so as to restore order and avert a White massacre in Kenya. Government security forces eventually quashed Mau Mau in a ruthless counterinsurgency campaign, yet conservatives still wished that the government’s response had been more violent.Footnote 95 But when the emergency ended, instead of admitting that White fears had been exaggerated, and that these fears stemmed from the untenable position of a privileged minority, conservatives like Goodhart made an about-turn and sought to belittle the threat of Mau Mau, a classic case of having your cake and eating it too.

Moreover, the explicit message in Goodhart’s remark was that by killing only thirty-two Europeans, Mau Mau had somehow failed in its objectives. It was as if the 1,819 executed Africans had been an afterthought, killed only to compensate for the scarcity of White targets. Given the widespread and uncritical acceptance of Goodhart’s problematic logic in the historiography, it is necessary to consider why Mau Mau members killed many more African than European or Asian civilians. To begin with, it is worth noting that the racial breakdown of Mau Mau’s civilian homicides was roughly proportional to the census data for 1948 and 1962, the only years for which reasonably accurate population records are available for all three races.Footnote 96 If anything, European fatalities showed the greatest variance with their population size. Because Europeans constituted only 0.5 and 0.6 percent of Kenya’s population in 1948 and 1962, the proportion of European civilians whom Mau Mau killed (1.7 percent) represented nearly three times their actual size in the population. Second, unlike most Africans, European and Asian civilians were more likely to own firearms for hunting and self-defense.Footnote 97 This high rate of gun ownership was as much a deterrent as an incentive for Mau Mau attackers who possessed few guns and even less ammunition.Footnote 98

Third and most important, African government informers posed the greatest threat to Mau Mau members, not European or Asian civilians. The fundamental flaw in Goodhart’s logic is that he sought to assess Mau Mau’s selection of targets based on the fears of White settlers rather than the priorities and objectives of Mau Mau members. He thus denied Mau Mau assailants agency in their own killing campaign. Even on White settler farms, where Europeans would have been easier targets, executing a Kikuyu foreman who threatened to report subversive activities on the farm was more urgent for Mau Mau members than eliminating the White farm owner, which only brought swift and severe reprisals from the authorities.Footnote 99 For example, after the November 1952 attack on the Meiklejohn farm in Laikipia, in which Ian Meiklejohn was the only fatality, the authorities evicted nearly 3,000 Kikuyu squatters from the district and sent them back to the reserves. They also seized 5,000 squatter cattle as collective punishment.Footnote 100

Such disproportionate responses to the homicides of White civilians forced Mau Mau units to think twice about killing Europeans. Even if the actual attackers managed to escape, the government increasingly used collective punishment against squatter communities that it suspected of harboring Mau Mau sympathies. Because Mau Mau sections that operated in the White Highlands could not survive without squatter support — especially after the government’s Operation Anvil in April 1954, which cut off Nairobi as the major source of supplies for the movement — guerrillas made efforts whenever possible not to kill European civilians.Footnote 101 By June 1953, there were reports of Mau Mau units plundering the properties of White settlers but deliberately sparing their lives.Footnote 102

To be sure, the government also used collective punishment measures in the reserves, which had the same effect of blunting Mau Mau attacks on African opponents. But the application of these measures varied greatly, depending on the status of the deceased. The killing of a high-profile chief elicited a stiffer response from the authorities than that of a little-known informer. In sum, Mau Mau guerrillas did not wage their asymmetrical anticolonial war in a vacuum. The moral logic of killing was grounded in the racial and class inequalities of late colonial Kenya. If the killing of one White man in Laikipia could lead to the seizure of 5,000 cattle and evictions of nearly 3,000 Kikuyu squatters from the district, then all lives in colonial Kenya were not equal. The racial breakdown of Mau Mau’s civilian homicides was a mirror of these gross inequalities. Raw casualty figures cannot therefore be divorced from their historical context and simplistically used to measure Mau Mau’s success or failure — as Goodhart and subsequent scholars of the Mau Mau War have attempted to do.

Fortunately, the captured documents allow for new and more useful racial comparisons that go beyond Goodhart’s reductionism to illuminate the moral logic of Mau Mau homicides. For example, of the ninety-six people whom Karari’s section killed, about fourteen appear to have had familial relationships. Karari did not include this information in his records, but it is possible to glean it from analyzing the surnames and sub-locations that he provided of the deceased. Karari’s section eliminated five sets of siblings. In Kaguyu, they executed three brothers from the Kiretai family, two brothers from the Kiura family, and two more brothers from the Manjuku family. In Kairia, the section killed two brothers and a sister from the Kimaru family and a brother and sister from the Gatungu family. They also eliminated a father and son in Kairia: Kimia Kagema and Kinguru Kimia.Footnote 103 Three of these five sets of siblings had at least one government informer among them. Similarly, the executed father was a screener, and his son was an informer.

These fourteen deceased represent only 15 percent of the total number killed, which indicates that the section’s homicides were highly targeted. If 85 percent of those executed did not have any familial relationships with each other, then Karari’s section selected their targets carefully. Adult men were the section’s primary enemies, representing 80 percent of those killed, while women and children constituted the remaining 20 percent. Assuming that adult men were likely to be husbands and fathers, it is striking that Karari’s section did not execute any couples and only eliminated one father and his adult son. These figures point toward a high degree of precision and restraint in the section’s killings.

In contrast, the homicides of White settlers appear to have been more indiscriminate.Footnote 104 Of the thirty-two Europeans whom Mau Mau killed, at least ten had familial relationships, representing a third of the total. They included couples as well as parents and their children, such as the Ruck family — Roger, Esme, and Michael — who lived in Kinangop, Nerena Meloncelli and her two children who were killed while visiting Nyeri, George and Dorothy Bruxnor-Randall who were residents of Thika, and Gray and Mary Leakey who lived in Nyeri. These ten targets constituted a White familial death rate of more than 30 percent, which was double the familial death rate of the African targets of Karari’s section. And it could have been worse. Mrs. Meiklejohn barely survived the attack that killed her husband; she suffered severe injuries to her head and body. Several other couples also survived Mau Mau attacks narrowly, including the Bindlosses of Kiambu and Tullochs of Thika who suffered serious injuries.

In addition, at least six women and six children died in the hands of Mau Mau assailants, representing nearly 40 percent of the European civilian death toll. Again, this was double the death rate of women and children whom Karari’s section killed. Admittedly, comparing the African targets of a single Mau Mau unit that operated in Nyeri to the European targets of multiple Mau Mau sections from across Central and Rift Valley Provinces has its limits. Yet as already demonstrated, the moral logic of Mau Mau killings transcended individual guerrilla units and specific battlefronts. Indeed, when the comparison is made at the macro level, the pattern remains consistent. Based on Wilkinson’s analysis of Mau Mau homicides, only 10 percent of the executed Africans were female, but among European civilians, White females constituted 22 percent of the total number killed.Footnote 105

In short, whichever way one analyzes the available evidence, the familial, women’s, and children’s death rates were twice as high for Mau Mau’s European enemies as for their African counterparts. As discussed earlier, Mau Mau members reimagined traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence to allow for the killings of African women and children who actively opposed Mau Mau. But as borne out by the nine-to-one ratio of executed male and female targets, Mau Mau assailants exercised great restraint because women and children were still a store and measure of wĩathi. In the case of White women and children, however, the evidence suggests that Mau Mau attackers exercised half as much restraint even when the targets were not active opponents of the movement. Nerena Meloncelli and her two children had only been in Kenya for ten days when they were killed. Michael Ruck was only six years old when he was hacked to death. It is unlikely that these targets had committed any perceived individual offenses against Mau Mau.

Nevertheless, Mau Mau members saw White women and children collectively as obstacles to their pursuit of wĩathi since they could still lay future claim to the White Highlands if allowed to live.Footnote 106 Far from being assets like Kikuyu women and children, guerrillas viewed White women and children as major liabilities that had to be eliminated. This moral logic of indiscriminate killings applied to landed African elites too. As David Anderson has shown in his “deeper history” of the Lari attacks, Mau Mau assailants indiscriminately killed women and children at Lari to prevent them from inheriting ill-gotten land.Footnote 107 Overall, of the 1,877 civilians whom Mau Mau assailants killed, 700–740 were suspected government informers (38 percent), 850–900 were government employees (47 percent), and 278–288 were government loyalists (15 percent).

Conclusion

During the anticolonial struggle in postwar Kenya, Mau Mau members reinvented a wide variety of traditional Kikuyu rituals, including oaths, prayers, animal sacrifices, divinatory practices, and funerary rites. At the same time, members of the movement reimagined traditional Kikuyu ethics of violence to guide their campaign of killing, plunder, and sabotage. This dual reconfiguration of ritual activities and ethics of violence formed a two-pronged process of sacralization within Mau Mau. Sacralization redrew the boundaries of what Mau Mau adherents deemed sacred, moral, and just measures for conducting the war. Yet the process of sacralization was hotly contested among Mau Mau members. It generated intense debates over questions such as the appropriate roles for female guerrillas, the justifiability of killing women and children, and the utility of seers and diviners in military operations. Sacralization thus refers not only to the process of making the Mau Mau struggle sacred but also that of debating and reimagining Kikuyu ethics, rituals, and beliefs. As the foregoing discussion has shown, the moral logic of Mau Mau killings was firmly rooted in a dialectical tension between longstanding Kikuyu ethics of violence and the harsh realities of waging an asymmetrical anticolonial war.Footnote 108

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Robert Maxon, John Lonsdale, the editors of the JAH, three anonymous reviewers, and my colleagues in the History Department’s Works in Progress forum at Tufts University for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts of this article.