Many social scientists have examined the causes, processes, and consequences of democratization in developing countries. What has propelled or hindered democratic transition and consolidation? In what ways has the nature of politics and society changed, or not changed, as a result of democratization? Why or why not? In addressing these important questions, the burgeoning democratization literatures have paid the lion's share of attention to the political party system, economic growth, cultural values, class structures, military coups, communal conflicts, social movements, and so forth.

In contrast, much less research has focused on the role of women, despite the fact that women's political representation has increased noticeably in recent decades. The bulk of available literatures concerns Western democracies (see Dolan, Deckman, and Swers Reference Dolan, Deckman and Swers2007 for a good review). Comparable literatures on Southeast Asia remain sparse, although they are slowly growing in number (e.g., Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2004; Dewi Reference Dewi2015; Iwanaga Reference Iwanaga2008a, Reference Iwanaga2008b). While there are many good historical, sociological, and ethnographic studies that dispel stereotyped myths about gender relations in the region (e.g., Andaya Reference Andaya2006; Bowie Reference Bowie2008; Fishel Reference Fishel2001; Keyes Reference Keyes1984), few political studies systematically address the nexus between democratization and female politicians. Thus, a recent book that provides comprehensive surveys of research on Southeast Asian politics contains no chapter on women (Kuhonta, Slater, and Vu Reference Kuhonta, Slater and Vu2008). This is not a biased oversight on the editors' part; rather, it indicates that there is too little scholarship on female politicians to survey. To help rectify this deficiency, I examine the rise of female politicians and its implications for the quality of democracy in Thailand, one of the most male-dominant countries in Asia.

Thailand moved seriously toward parliamentary democracy in 1973, when longstanding military rule was toppled by civilian demonstrators. Since then, the country has achieved much headway in increasing female political representation. Following the 1975 election, the first election held after 1973, only three women were in Parliament, comprising a mere 1.1 percent of all MPs. After the most recent 2011 election, Thailand had a record number of eighty-four female MPs, who made up 16.8 percent of the 500-member Lower House. Although this figure lags far behind some well-established Western democracies (e.g., 43.6 percent in Sweden), Thailand has surged ahead of two older democracies in Asia—Japan (10.1 percent) and India (11.8 percent) (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2017). Most notably, in 2011 Thailand produced its first female prime minister, Yingluck Shinawatra. Thailand has now joined the other countries in Asia that have placed women at the political helm.

What are the catalysts for these notable changes? In what ways has democratization contributed to the rise of female politicians? In turn, in what ways have women politicians shaped the nature of democratization? Have they made any difference in enhancing the quality of Thai politics? Examining these questions will reveal some of the opportunities, limits, and ironies that the introduction of competitive elections has brought to Thailand in the much-vaunted age of democratization.

Argument, Approach, and Sources

I argue that the majority of female MPs have contributed to growing family-based rule in Thailand. Their rise to power constitutes one essential part of the historical process through which political power has become concentrated in an increasingly limited number of elite families, rendering the nature of Thai democracy far from pluralistic. This is one ironic yet direct consequence of democratization. The post-1973 transition to democracy has only implanted Parliament and opened up vast opportunities for political participation for a myriad of political families without transforming the century-old patrimonial nature of the state. In this historical context, family-based rule has become all the more pronounced since 1973 as one salient manifestation of the patrimonial state. The specific families that compose this state may have changed over time, but family rule as a whole, of which female politicians are an increasingly important component, has stayed intact.

This argument is based on the finding that the majority of female MPs elected since 1975 are related, by blood or marriage, to former male MPs who come from entrenched, well-heeled political families. Yingluck, younger sister of the ousted Prime Minister Thaksin, exemplifies this pattern, but numerous other female politicians fall into the same category. I do not argue that all these women are “bad” politicians unfit to be in power. Judging from the frequency with which they have participated in parliamentary debates and the quality of issues and questions they have raised in those debates, a minority of female MPs seem to have taken their duties seriously (although most of the rest have performed badly).Footnote 1 My point is that regardless of how they have performed individually while in office, the female MPs from political families, taken as a whole, are implicated, if unintentionally or unknowingly, in the formation and consolidation of the family state in post-1973 Thailand. Some scholars have brought our attention to elite family rule in Thailand, but it has not been empirically and systematically demonstrated, especially with respect to female politicians (Kongkirati Reference Kongkirati2016; Ockey Reference Ockey2015; Rangsivek Reference Rangsivek2013; Thananithichot and Satidporn Reference Thananithichot and Satidporn2016). I attempt to fill this gap.

My argument defies the assumption that underlies one kind of nascent literatures on female politicians in Southeast Asia. Taking an implicit feminist stance, this literature bemoans the fact that politics remains men's “turf,” and identifies various obstacles to gender parity in politics (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013; Iwanaga Reference Iwanaga2008a, Reference Iwanaga2008b; Thompson and Thompson Reference Thompson and Thompson1994). The unstated assumption behind such analyses is that increasing women's numerical representation will lead to substantive democracy. As long as women constitute a minority in a male-dominated legislature, they feel inhibited from addressing “women's issues,” on which they have “expertise and experiences” (Iwanaga Reference Iwanaga2008b, 173, 174, 182).

I find such arguments uninspiring at best. At worst, they conjure up the romanticized image of women as a handicapped minority struggling to have their voices heard. Although many female candidates in Thailand market themselves politically along similar lines (Charoensuthipan Reference Charoensuthipan2007; Nation 2005; Raksaseri Reference Raksaseri2007), we should not take their rhetoric at face value. As Julie Dolan et al. (Reference Dolan, Deckman and Swers2007, 2) put it, feminist scholars tend to assume that “women differ from men, inadvertently suggesting that political women have more in common with one another than they do with political men. Although the temptation is to think of women as a monolithic bloc, the reality is much more complex.”

Instead of simply lamenting the political underrepresentation of women, we should ask what kinds of women have made it to public office, how they have gotten there, and what difference they have made in enhancing the character of democratization. This is the line of analysis taken by another type of incipient literatures, which I find more informative (Col Reference Col and Genovese1993; Derichs, Fleschenberg, and Hustebeck Reference Derichs, Fleschenberg and Hustebeck2006; Derichs and Thompson Reference Derichs and Thompson2013; Dewi Reference Dewi2015; Ockey Reference Ockey1999; Roces Reference Roces1998; Thompson Reference Thompson2002–3). Some of these literatures find, in line with my argument, that many female leaders in Asia come from politically and economically privileged families that produced prominent male politicians in the past. A prime example is former Filipino President Corazon Aquino, who was born into the powerful, landowning Cojuangco clan in Tarlac Province and married into another landowning family, the Aquinos, in the same province. This type of woman represents a fundamental continuation of the family-based elite rule that has long characterized the politics and economies of Southeast Asia (Anderson Reference Anderson1988; McCoy Reference McCoy1993; Robison Reference Robison1986; Roces Reference Roces2001; Suehiro Reference Suehiro1989).

Thus, Linda Richter (Reference Richter1990–91, 526) concludes: “There are very few female political leaders without links to politically prominent male relatives [in Asia].” Likewise, Farida Jalalzai (quoted in Branigan Reference Branigan2011) notes that “although numerically more men have capitalized on family connections, the proportion of women leaders with family ties is far higher. The phenomenon is also much more pronounced in south and south-east Asia … than other parts of the world, where female leaders tend to have emerged under their own steam” (see Chua-Eoan Reference Chua-Eoan1990 and Economist 2011 for similar views). Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (Reference Shair-Rosenfield2012) offers a theory that “female incumbency effects” explain the rising number of female politicians in post-Suharto Indonesia. That is, in the electoral districts where female politicians already exist, more women are likely to achieve electoral success in subsequent elections. This argument, however, does not undermine the view that family ties are crucial to women's electoral success. Shair-Rosenfield actually neglects to examine whether elected female candidates have kinship ties to male politicians—a glaring shortcoming of her seemingly comprehensive, statistically tested theory. Thus, her theory cannot explain how female incumbents get elected in the first place. To explain it, we must examine their family backgrounds. Indeed, Kurniawati Dewi's detailed empirical study shows that “familial ties [have become] a strong factor in the rise of female Javanese Muslim leaders” (Dewi Reference Dewi2015, 187, 189).

The existing works that highlight female politicians' kinship ties are not without flaws, however. None of them has conducted a comprehensive study of all national-level female legislators in any country; most focus narrowly on a handful of world-famous female leaders and overlook other less well-known women, many of whom are elected in the countryside. To overcome this weakness, I have examined all 251 Thai women who have won seats in both the Lower and Upper Houses, in a total of eighteen elections held between 1975 and 2014.Footnote 2 These MPs represent a sufficiently large number, making it possible to evaluate, longitudinally, what kinds of backgrounds female MPs have come from and what their emergence means for Thai politics. In what follows, I first present aggregate data on the women MPs from political clans and situate their electoral success within the broad context of growing family-based rule in Thailand. I then complement this data with several illustrative examples. I conclude by discussing my findings from theoretical and comparative perspectives.

My argument draws mainly on two hitherto untapped Thai-language primary sources. First is the “MP Files,” available at the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) archives in Bangkok. They contain valuable data on the personal, familial, and economic backgrounds of all MPs elected since 2007. Second is hundreds of “cremation volumes,” issued to commemorate the life stories of former politicians and their kin upon their deaths. Available at various libraries in Thailand and Japan, these volumes, although mostly hagiographic in nature, are excellent sources of information on the family genealogies and marriage ties of the deceased. I have supplemented these sources with snippets of information gleaned from Department of Commerce documents, parliamentary newsletters, biographies, newspapers, and Thai-language websites.

I define a political family or clan as: (1) the family or clan that has produced at least two MPs, male or female, since the first parliamentary election was held in 1933; or (2) the family or clan that has produced only one MP since 1933, yet is directly related by marriage to another family or clan that has produced one or more MPs during the same period. In accordance with the Thai notion of kinship (khrueayart เครือญาติ, wongsakhanayart วงศาคณาญาติ, wongwanwankhruea วงศ์วานว่านเครือ), this definition covers the patrilineal and matrilineal consanguineous ties of a particular MP, as well as his or her affinal relationships. If, for example, Family A has produced a female MP, whose son-in-law from Family B is also an MP, I treat both families as political families within the same kinship group, even though each family has produced just one MP. In other words, I have moved, wherever possible, beyond some scholars' works that simply use shared family names as the basic units of analysis (e.g., Ockey Reference Ockey2015). My conceptualization, critics might argue, runs the risk of stretching the notion of political families, but it has one big advantage that a mere analysis of shared family names does not: it helps capture the extent to which various seemingly unrelated MPs with different family names are actually tied to each other by blood or marriage. This mode of analysis thus conveys a better sense of the dynamics or complexity of kinship-based rule in Thailand.

Family Ties

Since 1975, a total of 2,502 MPs, including 251 women, have been elected in Thailand.Footnote 3 Of these women, 169 and 63 have been elected solely to the Lower House and Upper House respectively, while another 19 have gained seats in both. In terms of geographical regions, 233 female MPs have been elected from sixty of the seventy-seven provinces as constituency MPs and/or senators.Footnote 4

These seemingly innocuous facts, however, conceal an underlying, ominous trend toward the proliferation of female MPs from political families. Orapin Chaiyakan (1904–96), Thailand's first female MP (elected in Ubon Ratchathani in 1949, 1952, and 1958), set a precedent by coming from a prominent political family: prior to her political debut, her husband, Liang, had won eight consecutive elections between 1933 and 1957 (Chaiyakan Reference Chaiyakan1986). The proportion of female MPs from political families has been generally high since then, although it has fluctuated. Since the early 1990s, it has been on an upward trajectory (see table 1). In the 2011 Lower House election, nearly 73 percent of the eighty-four female MPs represented political families. Equally noteworthy is the fact that the senate, a supposedly neutral “high-quality” institution that monitors the politicized Lower House, has been deeply penetrated by political families. In 2006, the proportion of female senators from political families reached 82 percent (see also table 1). Altogether, out of the 251 women elected to the Lower and Upper Houses since 1975, 176 (70 percent) belong to political families.Footnote 5 Some women without any family connections have certainly won elections, thanks to their party affiliations or campaign slogans, but they constitute a conspicuous minority.Footnote 6

Table 1. Numbers of female MPs, 1933–2014.

Notes:

1. * indicates senate elections.

2. The figures in the last two rows indicate the number of female MPs from political families at the time of election. These figures more accurately reflect the extent of political families' dominance than a method of analysis that retrospectively identifies political families.

Sources: author's data set based on NACC MP files, cremation volumes, and other miscellaneous sources.

These developments, however, do not represent a historical aberration. Instead, they should be seen as but one integral part of century-old kinship-based rule in Thailand that has steadily become more and more entrenched over the decades. Table 2 indicates that during the 1933–71 period, almost 27 percent of the parliamentary seats contested in nine elections were won by MPs from political families—a historical legacy from the days of absolute monarchy, during which a coterie of noblemen linked to the court carved up the patrimonial state. For example, the Bunnags, the most powerful noble political family that had enjoyed affinal relationships with the Chakri dynasty since the Ayutthaya period (Wyatt Reference Wyatt1994, 116–17), produced three male MPs during the 1933–71 period (Bunnag Lineage Club 1999, 110–11, 184, 188). Another famous noble family, the Apaiwongs, which had ruled Battambang Province (now part of Cambodia) before 1932, produced five MPs for four different provinces before 1971, including Khuang, prime minister (1944–45, 1946, 1947–48), and his wife, Lekha, a Bangkok MP elected in 1969. Khuang's half-brother-in-law, Wibool Pokmontree, was also elected a Battambang MP in 1946 (Apaiwong Reference Apaiwong1968, 25, 35, 37).Footnote 7 At the same time, several commoner political families emerged as well. Of the fourteen female MPs elected before 1971, seven, including aforementioned Orapin Chaiyakan and Lai-aid Songkhram (MP for Nakhon Nayok, 1957), wife of Phibun (prime minister, 1938–44, 1947–57; Bangkok MP, 1957), belonged to such families.

The extent of family rule has increased appreciably since Thailand's democratization started in earnest in 1973. As competitive elections have taken deeper root (despite occasional setbacks), so has family rule. Families have become important, not just in business (Suehiro Reference Suehiro1989) but also in politics. The political families that emerged before 1971 have presumably produced powerful demonstration effects on politician-wannabes about how kinship ties can become “key institution[s] for linking power, wealth, and status in one generation and transmitting them to another” (Anderson Reference Anderson1977, 16). In particular, since Thailand entered the age of full-blown electoral politics in 1988, family rule has reached unprecedented proportions, with more than half the parliamentary seats going to political families, and 46.5 percent of all MPs hailing from those families, many of which have forged ties with each other by strategic marriage (see table 2). There have been 591 political families in post-1973 Thailand that account for 2,867 parliamentary seats altogether (or 4.9 seats/family) (author's data set). Many of these families, moreover, encompass different provinces without being confined to a single province (see below). Thus, Thailand's democracy has become increasingly closed to nonpolitical families; the scope of electoral competition has narrowed, making it more difficult for Thais to enter Parliament without having kinship connections. Electoral politics has ironically stifled political pluralism: the more electoral battles have been fought in the name of representative democracy, the more political inequalities have surfaced.

What concerns my argument most here is that the growing number of female MPs has contributed to the resilience and expansion of this kinship-based rule. In fact, they embody the primacy of kinship in Thai politics more than men. As noted above, of the 251 female MPs elected to Parliament since 1975, 176 (70 percent) belong to political families. By contrast, among all 2,251 male MPs elected since 1975, 895 (39.8 percent) come from political families (author's data set). Thus, female MPs are about twice as likely to represent political families as male MPs. This does not necessarily indicate that women are less capable politicians; rather it suggests that in the androcentric world of Thai politics, relying on well-tested kinship connections constitutes perhaps the easiest route to power.

These findings run counter to Elin Bjarnegård's theory. In explaining male dominance in Thai politics, Bjarnegård argues, essentially, that women are disadvantaged: male-dominated parties select male candidates over women to maximize their electoral chances in male-dominant Thai society, and male candidates then successfully deploy their clientelist networks to win office. This is how male dominance is reproduced, according to Bjarnegård (Reference Bjarnegård2013). What she ignores, however, is that women from political families, by virtue of their kinship ties to male MPs, possess extensive patron-client networks, too (Fishel Reference Fishel2001, 242–43). These networks, along with name recognition, give female candidates from political families enormous electoral advantages over other candidates (including men) from nonpolitical families. Accordingly, many parties have come to field such women as candidates. Thus, political lineage, rather than gender, affects the selection of candidates. This explains what Bjarnegård's theory cannot explain—why, in reality, more and more Thai women have made inroads into Parliament.

Patterns of Succession and Power-Sharing

Depending on the patterns of intrafamily political succession and power-sharing, we can identify two types of female MPs. First is “trailblazers.” They are the first to become MPs in their respective families, and after they retire, die, or lose their jobs (e.g., through coups), their kin, male or female, take over as new MPs. A case in point is Sunirat Telan (1920–95). Originally from Bangkok, Sunirat became an MP for three provinces (Nakhon Sawan, Ranong, and Roiet) in 1952, 1957 (December), and 1975, respectively,Footnote 8 before her second son, Thanet, was elected a Nakhon Sawan MP in 1976 (Telan Reference Telan1995).Footnote 9 Similarly, Nipa Pringsulaka (b. 1936) passed her office on to her only son, Thirapat, after serving as a Surat Thani MP (1992–2011) (NACC 2011i). Some other cases have involved transfers of power from wife to husband, as exemplified by Anchalee Thepabutr, a hotel tycoon and Phuket MP (1995–2006, 2011–14), whose husband, Tossapon, became also a Phuket MP in 2007. In 2008, Anchalee's cousin, Manopnoi Wanit, was elected a senator for the neighboring Phan-nga Province (NACC 2008b). More sensationally, the assassination in May 2006 of Kopkul Nop-amonbodi, a Ratchaburi MP (elected in 2001 and 2005), prompted her husband, construction business tycoon Manit, to win a parliamentary seat in her place in 2007. In 2006 and 2008, Kopkul's younger brother, Kecha Saksomboon, was elected a Ratchaburi senator, while his wife (or Kopkul's sister-in-law), Piangpen, followed suit in 2014 (NACC 2008a, 2014). Three other cases involved a transfer of power from a female trailblazer to her female kin. For example, Sunee Inchat (Sisaket senator, 2001–6) bequeathed her office to her two daughters, Malinee (Sisaket MP, 2005–6; party-list MP, 2011–14) and Wilada (Sisaket senator, 2014) (NACC 2011k).

These and other trailblazers, however, constitute a distinct minority—just twelve (6.8 percent) of the 176 female MPs elected from political families since 1975.Footnote 10 The vast majority (n = 164) belong to the second category of female MPs—“political inheritors or partners.” In the cases of these women, the pattern of political succession is reversed: their male kin become MPs first, and after they die, retire, or lose office, their female kinfolk—wives, daughters, sisters, in-laws, nieces, and so forth—fill their shoes as political inheritors. In other cases, while male MPs are still in power, their female kin win office and share power as political partners. These female MPs have followed the paths taken by their male-kin predecessors.

In terms of specific kinship ties, seventy-five (45.7 percent) of the 164 female political inheritors or partners are the wives of former male MPs, while thirty-nine and thirty-seven have taken over political power from, or shared it with, their fathers and brothers, respectively. Remarkably, 101 (61.6 percent) of the female political inheritors or partners have had at least two male- or female-kin political predecessors or power-sharing partners.Footnote 11 Yingluck represents the best example of such MPs with multiple kinship ties. Her two elder brothers (Thaksin and Payap), father (Lert), and uncle (Surapan), along with her elder sister (Yaowapa) and niece (Chinnicha), have all become MPs.

Extending Jason Brownlee's terminology, we might say that these intrafamily, intergenerational political successions represent “hereditary succession through competitive elections.” Brownlee talks only about hereditary succession within authoritarian states, in which autocrats' sons, daughters, and other kin inherit political power on the autocrats' retirement or death (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007). Kinship-based political successions, however, occur in fledgling democracies too, as ruling elite families take advantage of electoral politics to hand down their powers to their familial heirs apparent, including women. Many of these families have achieved transfers of power without relying on female kin, but for some other families, intergenerational power transfers have necessitated (at least partial) reliance on women. To build on Kasian Tejapira's concept, these women, along with their male counterparts, can be called “hereditary electrocrats” (Tejapira Reference Tejapira2006)—politicians who are good at winning elections by dint of their kinship ties, although success is by no means guaranteed in Thailand's increasingly competitive elections.

Catalysts

One unexpected impetus for the growing number of female MPs has come from outside their families: a series of politicized Constitutional Court rulings issued after the 2006 coup. The first ruling, issued in 2007, dissolved Thaksin's Thai Rak Thai (TRT) Party and deprived its 111 high-ranking members of their political rights for five years. In 2008, the Court dismantled the People's Power Party (PPP), a TRT reincarnation, and two other parties: Chart Thai and Matchimatipatai. The ruling barred 109 members of these three parties from politics for five years. To compensate for their loss of power, many banned male politicians have had their kin, including women, attain office on their behalf. Of the seventy-seven female constituency MPs elected from political families in the post-Thaksin period, twenty-six (33.8 percent) fit this pattern. As Banharn Silpa-archa, leader of the dismantled Chart Thai Party, said, “There will be nominees [of the banned MPs] across the country. If a husband is banned, his wife or his offspring will replace him” (Sattaburut and Laohong Reference Sattaburut and Laohong2008). Thus, one important catalyst for women's foray into politics has been to fill the political void left by their male kinfolk. This trend supports Jalalzai's point that women from political clans enter politics “in politically unstable contexts and in countries lacking political institutionalization…” (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2008, 207). Chua-Eoan (Reference Chua-Eoan1990, 35) put it similarly: “When chaos and violence rob a family of vigorous male representation, it's … women who then pursue the clan's goals….” Many Thai women's political debuts were necessitated by such externally generated political exigencies.

There is a limit, however, to using the dramatic post-2006 developments to explain the rising number of female MPs from political families. This is because even the families unaffected by the 2006 coup and the subsequent Court rulings have had their female kin become MPs. In the cases of these families, the motives or incentives for hereditary succession have come from within. That is, as the previous generation of male MPs have gotten older and retired or died, their families have made strenuous efforts, since long before 2006, to groom their kin, including women, as their successors or power-sharing partners. Thus, the external shocks in post-2006 Thailand have only accelerated, but not triggered, the larger historical process through which political clans have sought to ensure a transfer of power from generation to generation.

Case Studies

This section sheds light on several specific political families and their female MPs, whose entry into politics has been motivated by the need to retain or expand the power bases that their male kin had previously established.

The Tienthongs

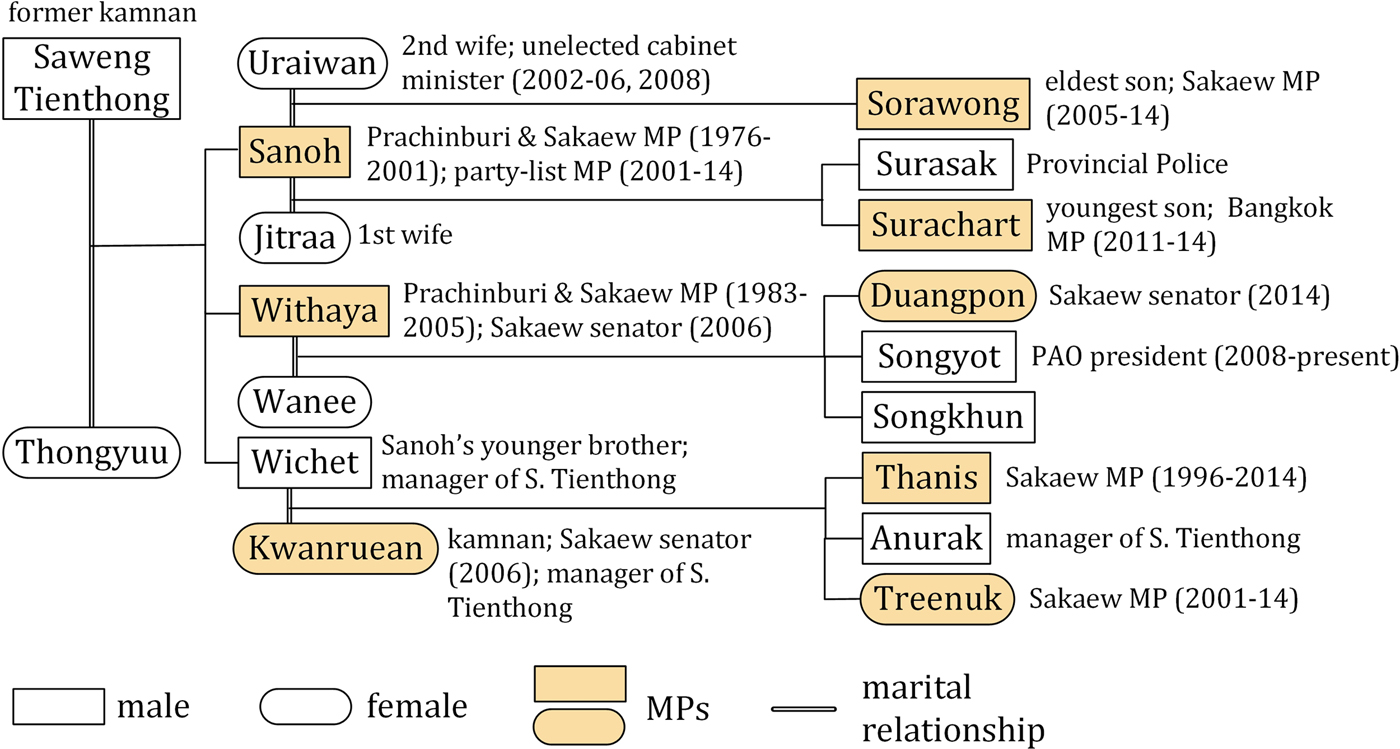

Sakaew Province near Cambodia is the stronghold of the Tienthong clan, which has thus far produced three female MPs. Their rise to power constitutes three small yet indispensable building blocks of the powerful provincial dynasty that the current patriarch, Sanoh, has endeavored, with phenomenal success, to establish over the last four decades by relying on his multiple kin.

Sanoh was born in 1934 into an influential Chinese immigrant family in Prachinburi Province (of which Sakaew was a part until 1993). His father, Saweng, a subdistrict head, owned a whopping 6,000 rai of land (1 rai = 1,600 square meters), engaged in then-legalized opium production, and held a monopoly to sell wood to the Thailand Railway Authority. When Saweng died in 1946, Sanoh, then aged twelve, took over the family's economic activities, along with his elder siblings. In 1959, Sanoh established a retail business, S.Tienthong, after winning a public bid to become the sole distributor of liquor in his home district. In the 1960s, as the central state pursued massive rural infrastructure development, S.Tienthong (now renamed SPT Civil Group) expanded into road construction (DBD/MC 1970a; Ladamanee Reference Ladamanee2001, 22–38). In 1987 and 1989, Sanoh also established a dairy firm, Wang Namyen Dairy Cooperative, and a real estate company, Golden Gate (DBD/MC 1989a), respectively. Sanoh and his wife own 1,853 rai of land worth more than seventy-five million baht in Sakaew alone (NACC 2011f). In the 1990s, he founded two additional construction companies, P.T.A. Construction and Sakaew Concrete Products (DBD/MC 1992, 1993).

These copious economic resources have enabled Sanoh to pursue a successful political career and hold several key cabinet posts. He has the longest winning streak among all Thai MPs: he won a landslide victory in every election between 1976 and 2001, after which he moved to the party list to allow his next-generation kin to become constituency MPs. Along the way, Sanoh has turned Sakaew into his family's fiefdom. He took his first step in this direction in 1983 by having his younger brother, Withaya, elected as Sakaew's MP. Sanoh then pressured his protégé, Burin Hiranburana (MP, 1986–96), not to run for office in the 1996 election, and Burin's seat was filled by Thanis, Sanoh's nephew (or the son of his now-dead youngest brother Phichet). Since that year, all seats in Sakaew have been monopolized by the Tienthongs.

In 2001, as Sanoh moved to the TRT party list, Thanis's younger sister, Treenuk (b. 1972), then aged twenty-nine, stepped into his shoes as a new constituency MP. She became the first female MP for Sakaew. Despite the fact that she was a first-time candidate competing against ten men, she finished first; she won by a wide margin, garnering over 90 percent of the vote (Election Commission 2001, 352). Furthermore, in 2005, Sorawong, Sanoh's eldest son by his second wife Uraiwan (who was appointed minister of culture twice in the 2000s without being an MP), became a new MP on Withaya's behalf, while Withaya was elected a senator a year later, along with Kwanruean (b. 1944), Treenuk's mother. Sorawong, Thanis, and Treenuk now occupied all three seats in Sakaew as second-generation MPs from TRT. After TRT was dissolved, the three won reelection in 2007 from the Pracharaj Party, of which Sanoh became leader. In 2011, they were all reelected, this time from Yingluck's Phuea Thai Party, along with Sanoh, a party-list MP. In Yingluck's government, Sorawong was appointed deputy minister of public health (2013–14), while Thanis became deputy interior minister (2011–12), a powerful post that controls the appointments of governors and district chiefs nationwide, and deputy industry minister (2012–13). To further extend their power beyond Sakaew, the Tienthongs got a foothold in Bangkok in 2011, when Surachart, Sanoh's (and his first wife Jitraa's) youngest son and manager of Thai Beverages, which produces the internationally distributed Beer Chang, became an MP (NACC 2011g). Most recently, Sanoh's niece (or Withaya's daughter), Duangpon (b. 1965), won the 2014 senate election. Meanwhile, at the provincial level, Songyot, Sanoh's nephew (Withaya's son), has since 2008 served as chairman of the Provincial Administrative Organization, whereas another of Withaya's sons, Songkhun, was mayor of Sakaew Muang municipality (2000–2007), before he was murdered in 2010 (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Intrafamily political connections of the Tienthongs. Sources: NACC files and miscellaneous others.

Thus, under Sanoh's leadership, the Tienthongs have established a political stranglehold on Sakaew, to a degree that is unmatched elsewhere in Thailand; no other province is more solidly controlled by one family. At age eighty-three (as of January 2018), Sanoh will not be alive for much longer, but he must find comfort in the fact that the process of intrafamily, intergenerational political succession has been eminently successful. The significance of Treenuk's emergence as the first female MP for Sakaew, as well as her mother's and relative's electoral successes, can be best understood in terms of this family-based political inheritance.

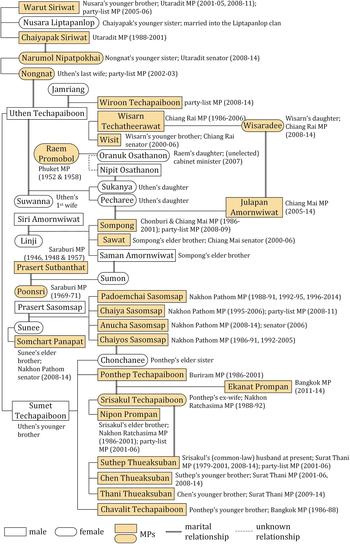

The Techapaiboons

Srisakul and Nongnat Techapaiboon are two other female MPs who have inherited political power from, and have shared it with, multiple male kin under Thailand's family-based democracy. Both are related, by marriage, to the late Uthen Techapaiboon (1913–2007), the Sino-Thai founder of the powerful Bangkok Metropolitan Bank conglomerate that once controlled seventy-seven companies (Suehiro Reference Suehiro1989, 295–97). The emergence of these female MPs has much to do with Uthen's attempt to translate his clan's economic power into political power. As Ponthep Techapaiboon, Uthen's nephew, explained, “In the past, we used to work together with politicians, but they sometimes [bullied] us. So my father [Sumet, Uthen's younger brother] decided that my generation had to enter politics, [so that] we could not be [bullied]. He said, ‘I will make the money; you go into politics'” (quoted in Rangsivek Reference Rangsivek2013, 124).Footnote 12 Along the way, Uthen's extended kinship groups have produced two additional female MPs. The result is an interlocking, entangled web of political ties that involve nine provinces, including Bangkok, and four female MPs (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Political family connections of the Techapaiboons. Sources: NACC files; Amornwiwat (Reference Amornwiwat1986); Bunyaprasop (Reference Bunyaprasop2008); Rangsivek (Reference Rangsivek2013); Techapaiboon (Reference Techapaiboon2008).

The first action Uthen took to pursue his political project was to cultivate two sons of his brother Sumet—Ponthep and Chavalit—as Democrat Party MPs for Buriram in the northeast (1986–2001) and Bangkok (1986–88), respectively. Following their electoral victories, Srisakul (b. 1955), Ponthep's (now divorced) wife, became a Democrat Party MP for another northeastern province, Nakhon Ratchasima (1988–92). Meanwhile, Srisakul's elder brother, Niphon Prompan, served as Nakhon Ratchasima's Democrat MP (1986–2001) by winning six successive elections, after which he became a Democrat party-list MP (2001–6). Ponthep and Srisakul have three children, the youngest of whom is Ekanat. At age twenty-five, Ekanat became Bangkok's Democrat Party MP in 2011 as a successor to his parents and uncle (NACC 2011a).

Srisakul's current common-law husband is Suthep Thueaksuban, former Democrat Party secretary-general, a constituency MP for the southern province of Surat Thani (1979–2001, 2008–14), and party-list MP (2001–6). Suthep, once involved in a major land scandal in 1995, wields enormous political influence, based on his ownership of over 842 rai of land worth ninety-eight million baht, all in Surat Thani (NACC 2011h). Thanks to this influence, his two younger brothers, Chen and Thani, also served as Democrat MPs for Surat Thani until 2014. In 2008, Suthep took in the aforementioned Ekanat, Srisakul's son, as his secretary, and successfully groomed him as a Democrat candidate in the 2011 Lower House election. Thus, Suthep has enabled the Techapaiboons to maintain a measure of influence with the pro-monarchical Democrat Party, the oldest party in Thailand.

The Techapaiboons have extended their political influence to northern Thailand, too, by siding with non-Democrat parties. This is where Nongnat (b. 1958), Uthen's sixth (and last) wife and a party-list MP from the Chart Phattana Party (2002–3), comes into the picture. She comes from a prominent political family in Utaradit Province. Her younger sister, Narumol Nipatpokhai (b. 1959), became Utaradit's senator in 2008 as the Techapaiboon group's third female-kin politician (NACC 2008c). Moreover, Narumol's husband, Chaiyapak Siriwat, was elected a constituency MP for Utaradit five consecutive times in 1988–2001. Chaiyapak's younger sister, Nusara, has married into the Liptapanlop clan led by Suwat—leader of the Chart Phattana Party (to which Nongnat belonged), Nakhon Ratchasima's constituency MP (1988–2001), and party-list MP (2001–6). Suwat's wife, Punpirom, also became Nakhon Ratchasima's senator (2006). After Chaiyapak washed his hands of politics in 2001, his younger brother, Warut, served as Utaradit's MP (2001–5, 2008–11) and TRT party-list MP (2005–6) (NACC 2007b). Nongnat has been a liaison of sort among these families.

The Techapaiboons have established a political base in another two northern provinces—Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai—through Pecharee, one of Uthen's two daughters born to his first wife, Suwanna. Pecharee has married Sompong Amornwiwat, who was elected a Chonburi MP (1986), Chiang Mai MP (1988–2001), and party-list MP (2008–11) (Techapaiboon Reference Techapaiboon2008, 168). Sompong's elder brother, Sawat, was Chiang Mai's senator (2000–2006). Another of Sompong's elder brothers, Samarn, married Sumon, daughter of two former Saraburi MPs elected before 1973—Prasert Sutbanthat (1946, 1948, and 1957) and his wife, Poonsri (1969) (Amornwiwat Reference Amornwiwat1986, 3; Prasert Sutbanthat Reference Sutbanthat1980; Poonsri Sutbanthat Reference Sutbanthat1997, 38). What is more, Sompong and Pecharee have four children, the youngest of whom is Julapan, another Chiang Mai MP (2005–14). In April 2010, Julapan, Uthen's grandson, married Wisaradee Techatheerawat, whose father, Wisarn, served as Chiang Rai's TRT MP (1986–2006), until a court ruling imposed a five-year ban on his political career. Wisaradee, then aged only twenty-six, replaced Wisarn as his proxy in 2007; she became a fourth female MP in Uthen's kinship group (NACC 2007c). Wisaradee is also the niece of Wisit Techatheerawat, Chiang Rai's senator (2000–2006).

Another of Uthen's daughters, Sukanya, has married into the Osathanon family, to which Raem (Promobol) Bunyaprasop (1911–2008), Thailand's second female MP (elected in Phuket in 1952 and 1958), is tied. Raem's daughter, Oranuk (b. 1938), has married Weera Osathanon, whose father, Wilas, was deputy minister of transport (1941) and minister of commerce (1946–47). Oranuk was appointed deputy commerce minister in Surayud Chulanond's interim government after the 2006 coup (Bunyaprasop Reference Bunyaprasop2008, 19; Osathanon Reference Osathanon1997, 20–22; Techapaiboon Reference Techapaiboon2008, 167).

Uthen's political family ties know few bounds. The aforementioned Ponthep's elder sister, Chonchanee, is married to Chaiyos Sasomsap, Nakhon Pathom's veteran five-time MP (1986–2001) and party-list MP (2001–5). The Sasomsaps are the most influential political family in Nakhon Pathom: besides Chaiyos, his three brothers—Padoemchai, Chaiya, and Anucha—have become constituency MPs since the 1980s. In 2008, Somchart Panapat, their uncle (or elder brother of their mother, Sunee), became Nakhon Pathom's senator, too (NACC 2008e). To top it all off, in the 2000s, the Techapaiboons groomed Wiroon, one of the six children Uthen fathered by another of his wives, Jamriang, as a politician (NACC 2007d). In the 2007 election, held one month after Uthen's death (at age ninety-four), Wiroon became a PPP party-list MP. He was reelected a Phuea Thai party-list MP in 2011. During his terms in office, Wiroon served as deputy finance minister twice (2008, 2011–12).

Thus, the political connections of the economically powerful Techapaiboon clan have ramified, over three generations, in all sorts of directions, involving ten families in nine provinces and transcending party lines. A shrewd political chameleon, Uthen spread risks by supporting a spectrum of parties, so that whichever party or regime assumed power, his clan was able to maintain a degree of political clout. He probably thought it prudent to avoid putting all his eggs in one basket, given the highly volatile nature of Thai politics. The family has succeeded admirably in pursuing its political agenda by capitalizing on the advent of much-touted democracy. The four female MPs examined here supply four of the many pieces of this success.

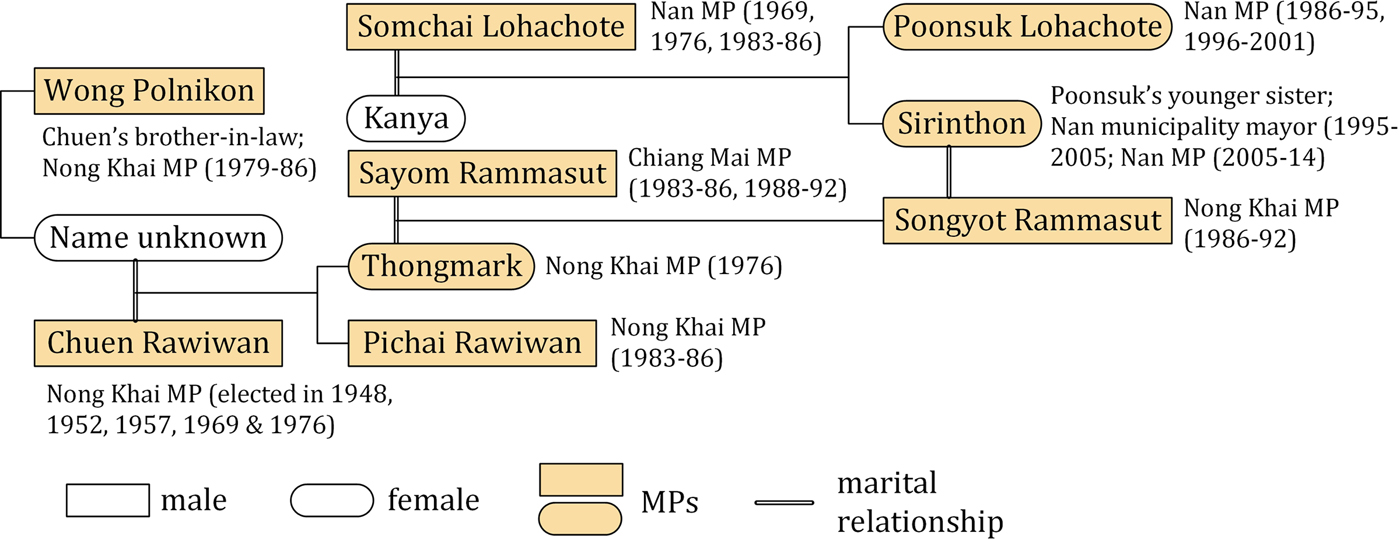

The Lohachotes, Rammasuts, and Rawiwans

On a more limited yet significant scale, the Lohachote clan in the northern province of Nan has established political kinship connections that straddle two provinces (see figure 3). This clan was founded by Luang Thananuson (Chuang), Nan's first finance ministry official, on whom King Vajiravudh (Rama VI) conferred Lohachote as a surname in January 1919 (Sunthrasanthul Reference Sunthrasanthul2013, 641). The family has made its wealth in tobacco-curing—one of the oldest and the most profitable economic activities in northern Thailand—by running Nan Leaf Tobacco Corporation (DBD/MC 1968), but now also runs a chain of supermarkets in Nan (NACC 2007a). In the post-1973 period, this family has produced two female MPs—Poonsuk and Sirinthon.

Figure 3. Political family connections of the Lohachotes, Rammasuts, and Rawiwans. Sources: NACC files; Kritiyapichatkul (Reference Kritiyapichatkul1998).

Poonsuk (b. 1959) became Nan's MP in 1986, at age twenty-seven, as a successor to her (now deceased) father, Somchai. A veteran MP, Somchai was first elected in 1969, after having served as Nan's provincial councilor since 1952 (Kritiyapichatkul Reference Kritiyapichatkul1998, 83). He was reelected in 1976 and 1983. To ensure his clan's political longevity, the aging Somchai fielded his daughter, Poonsuk, as a Chart Thai Party candidate in the 1986 election. She won this and four subsequent elections, until she suffered a crushing defeat in 2001 to Khamron na Lamphun, a six-time Democrat MP and a descendant of the ruling aristocratic clan in Lampun Province that had produced two other MPs since the 1930s. An heir to this tradition, Khamrong made a political debut in 1979, after which he won five elections in Nan. Poonsuk's loss to Khamrong in 2001 took place in the context of this rivalry between two noble families in Nan. Presumably alarmed by the prospects of losing his political influence, Somchai cultivated Sirinthon (b. 1960), Poonsuk's younger sister, as an alternative second-generation heir in the next election in 2005. Sirinthon was no political neophyte, having served as mayor of the Nan Muang Municipality for ten years (1995–2005). Sirinthon faced, yet defeated, Khamron's wife, Sukanya. Sirinthon won reelection in 2007 and 2011.

Meanwhile, the Lohachotes have established marriage ties to another entrenched political family in the northeastern province of Nong Khai—the Rammasuts. Rammasut is another royally bestowed surname—bestowed by Rama VI on Khun Worapatbanharn (Lian), a Customs Department official, in December 1913 (Sunthrasanthul Reference Sunthrasanthul2013, 100). This clan produced Songyot, a three-time Nong Khai MP (1986–92), whom Sirinthon Lohachote married in 1995. Songyot's mother, Thongmark (b. 1933), had become Nong Khai's first female MP in 1976 (Ratthasaphasarn 1976, 91), while his father, Sayom, served as an MP (1983–86, 1988–92) in another province, Chiang Mai. Thongmark herself comes from another distinguished political family in Nong Khai—the Rawiwans: her father, Chuen, was first elected to Parliament in 1948, and won reelection in 1952, 1957, 1969, and 1976. Chuen's son, Pichai Rawiwan, and brother-in-law, Wong Polnikon, also served as Nong Khai MPs in 1983–86 and 1979–86, respectively (Kritiyapichatkul Reference Kritiyapichatkul1998, 209–13).

Although the bases of popular support for these three families have been less than rock-solid (as exemplified by their occasional electoral losses), and the Rammasuts and Rawiwans are no longer politically active in Nong Khai, the marriage between Songyot and Sirinthon has brought into being an interprovincial political coalition that has achieved generally successful intrafamily and interfamily transfers of power in the space of six-odd decades. Sirinthon, her sister Poonsuk, and her mother-in-law Thongmark constitute three elements of this political succession.

The Seriraks and Uea-apinyakuls

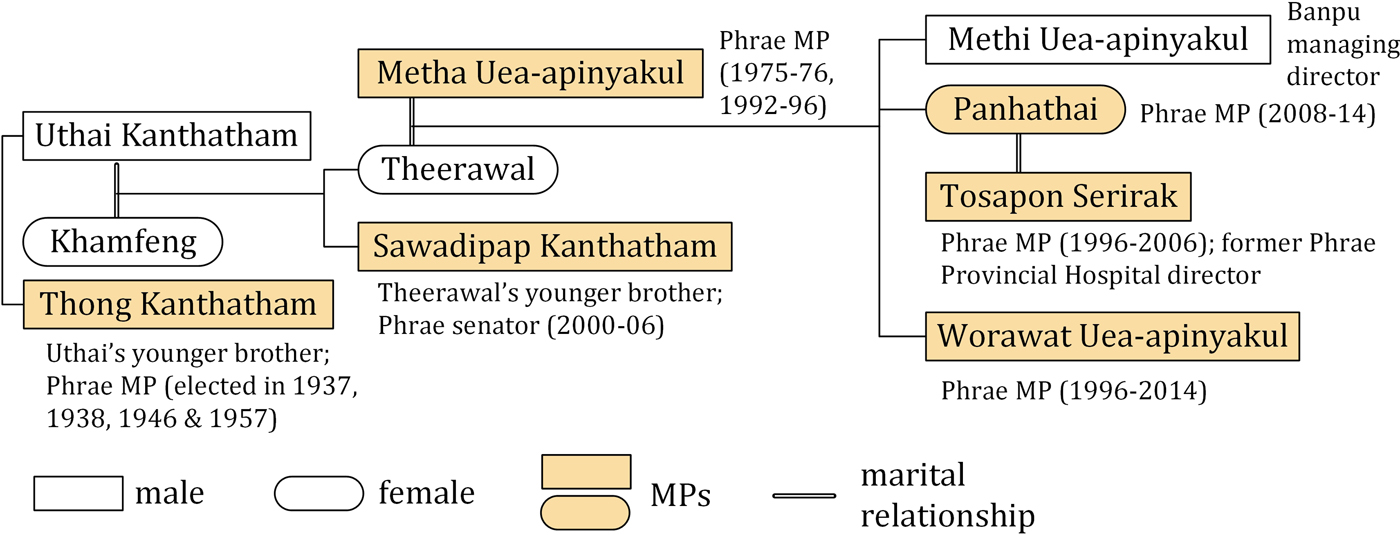

Panhathai Serirak (b. 1955), an MP for the northern province of Phrae, is another woman who has held political office as an heir to, and a partner with, multiple male kin. Despite its relative small size and population, Phrae has thus far produced three female MPs including Panhathai, and her rise to power can best be understood in the context of the ebb and flow of Phrae's various political families, including her own.

Panhathai hails from the locally eminent Uea-apinyakul clan. She is the daughter of Metha, Phrae MP (1975–76), who accumulated his wealth in tobacco curing (Lanna Tobacco) and minerals extraction (Banpu—Thailand's foremost coal company) (DBD/MC 1983, 1989b).Footnote 13 Metha is a son-in-law of Uthai Kanthatham (1907–89), whose younger brother, Thong, was the most prominent Phrae MP before the 1970s, having been elected in 1937, 1938, 1946, and 1957 (Kanthatham Reference Kanthatham1990, 1). Metha was a political successor to Thong.

Following his initial electoral success, Metha subsequently ran for office three times, but to no avail. Meanwhile, politics in Phrae fell into the hands of two other clans—the Rangkhasiris and the Wongwans. The former family produced Buakhiaw (1913–88), director (1943–74) of Phrae's prestigious women's school Narirat and Phrae's first female MP, who won two successive elections of 1975 and 1976. Buakhiaw's mother, Sukhantha, was descended from the illustrious Saensiriphan family that had ruled Phrae during the period of absolute monarchy. Sukantha's younger brother (or Buakhiaw's uncle), Wong, became Phrae's first MP in 1933. Following this political tradition, Buakhiaw became an MP in 1975 after her husband, Sathit, died. Subsequently, one of her two sons, Dusit, a former provincial councilor, took over and served as Phrae's MP until 1996 by winning seven consecutive elections (Napasri Reference Napasri2002, 56, 58; Rangkhasiri Reference Rangkhasiri1988, 15–18).

The Wongwan family, for its part, revolved around Narong (b. 1925). His family operated phenomenally lucrative logging and tobacco-curing companies, including Thepawong, Siam Tobacco Export Corporation, Thai Tobacco Industrial, and General Tobacco (DBD/MC 1949, 1965, 1970b, 1974). Narong was also an alleged narcotics trafficker on the United States government's blacklist. Relying on these economic resources, Narong reigned supreme as Phrae's MP between 1979 and 1995, along with aforementioned Dusit, while Narong's younger brother and eldest son, Sangwal and Anuson respectively, became MPs in the neighboring province of Lamphun.

Presumably threatened by the growing domination of these two families, Metha returned to politics as an MP in March and September 1992 by forming an electoral alliance with Narong. Soon thereafter, the Wongwans and Rangkhasiris fell from power, much to the benefit of Metha's family. This unexpected realignment of local politics originated in 1992–93, when the United States started tightening the screws on drug traffickers, dealing a severe blow to Narong's economic fortunes. Accordingly, his patronage network shrank, as exemplified by the defection of his longtime “trusted” vote canvasser, Sanit Supasiri. Sanit even had his daughter, Siriwan Prasarjarksatru (b. 1956), contest the 1995 election against Narong. Deprived of his electoral machine, the seasoned Narong, then aged seventy, suffered a humiliating loss to the much younger Siriwan, a greenhorn candidate, while Metha won another seat in Phrae. This loss led Narong to wash his hands of politics. In the subsequent 1996 election, furthermore, Siriwan routed Dusit, causing him to call it quits in politics, too. With no successor in line, his family's political fortunes evaporated.

In the meantime, Metha's family survived the vicissitudes of local politics. Although he retired from politics before the 1996 election (due to old age), the youngest of his four children, Worawat, and Metha's son-in-law (Panhathai's husband), Tosapon Serirak, took his place as new third-generation MPs counting from Thong Kanthatham (NACC 2011b). Worawat and Tosapon won office, along with Siriwan Prasarjarksatru. The three won reelection in 2001. Meanwhile, in 2000, Thong's nephew (or Uthai's son), Sawadipap, former director of the Budget Bureau, was elected a Phrae senator, too (Kanthatham Reference Kanthatham1990, 1). Thus, from the mid-1990s onwards, politics in Phrae saw two extended families—Siriwan's Prasarjarksatrus and Supasiris and Metha's Uea-apinyakuls and Seriraks—vie for supremacy.

The rivalry did not last long, however. In the 2005 election, Narong's second son, Anuwat, defeated Siriwan in an act of political revenge, while Worawat and Tosapon scored comfortable victories as TRT candidates. The reputation of Siriwan's family was then irreparably compromised in October 2007, when she was suspected of being behind the ghastly murder of Charnchai Silapauaychai, president of the Provincial Administration Organization (PAO). He was shot dead while jogging in a public park in the morning. According to a provincial newspaper (Siang Phrae 2007), Pongsawat Supasiri, Siriwan's younger brother and PAO member, clashed with Charnchai over the use of a 120-million-baht bank loan. Siriwan was also reportedly offended when Charnchai, a former supporter of the Democrat Party, to which she belonged, avowed his support for her rival candidates in the 2007 Lower House elections scheduled two months later. Although Siriwan, as well as Pongsawat, was cleared of suspicion, this murder case led to her electoral loss again. Meanwhile, in the Court ruling issued seven months prior to this election, the Uea-apinyakuls and Seriraks suffered a setback too, as Tosapon, a TRT executive, was stripped of his political power. The clan adjusted to this loss, however, by having his wife, Panhathai, win office, along with his younger brother, Worawat (see figure 4). She was her husband's proxy.

Figure 4. Political family connections of the Uea-apinyakuls and Seriraks. Sources: NACC files; Kanthatham (Reference Kanthatham1990).

Another unexpected development has contributed further to consolidating the position of the Uea-apinyakuls and Seriraks. Three weeks before the 2007 Lower House election, Phrae held a PAO by-election to find a replacement for the slain Charnchai. Instead of seeking reelection in the Lower House, the incumbent MP Anuwat, Narong's son, decided to contest the PAO election, which he won. (He remained PAO president as of January 2018.) Although the PAO presidency is an extremely important position, its influence is limited to the provincial level, and the Wongwans have now been reduced to a “second-tier” political family in Phrae. This development, coupled with Siriwan's fall from grace, signified the rise of the Uea-apinyakuls and Seriraks as the most influential family in Phrae.

The 2011 Lower House election saw this dominance continue. Both Panhathai and Worawat won reelection as Phuea Thai MPs. Siriwan made a partial comeback as a Democrat party-list MP. (She was put on the party list, presumably because she stood little chance of winning against Panhathai and Worawat.) Her election, however, did little to shake the Uea-apinyakuls' and Seriraks' dominance. Thus, along with Worawat, Panhathai has helped her family attain its current position as a valuable successor to her grandfather's brother, father, and husband, while the relative positions of other political families have diminished.

The Thai Family State: The Weight of History and Culture

Thai women have come a long way in politics. Before monogamy was legalized in 1935, polygamous marriages signified the monarchs' sexual prowess, and noble families willingly offered their daughters to the court to form political alliances (Loos Reference Loos2006, 110–17; Reynolds Reference Reynolds and Reynolds2006, 192–95). The women's bodies only mediated political loyalties back then. Now, they represent political authority itself, as many elite families have successfully placed their female kin in Parliament.

The cases of female MPs discussed above (and many others) suggest, however, that the family-based nature of Thai politics has changed little since the era of absolute monarchy, when numerous male scions of polygynous rulers and other nobles monopolized positions at the pinnacle of the state, often despite their “tender ages and lack of relevant experience” (Loos Reference Loos2006, 51), and “hereditary succession in the governorships was clearly the norm in many provinces” (Vickery Reference Vickery1970, 866). Some of these positions were created by the ruler, not to enhance administrative efficiency but to “protect the succession of his favorite son or … the son of his favorite wife” in the first place (Wolters Reference Wolters1999, 143). Consequently, there was no “state” in the strict sense of the term. “The ‘state’ of Siam was constituted less by formal institutions than by royal-blooded men, nobles, and provincial elites, all of whom intermarried” (Loos Reference Loos2006, 110; see also Cushman Reference Cushman and Reynolds1991, 122). Over the past eight-odd decades since then, countless regimes have risen and fallen thanks to coups or protests and a plethora of electoral laws and constitutions have been written and rewritten, yet underneath these outwardly significant developments, elite families have consistently made the “state.” The majority of female MPs belong to such families. While these women have carved out political space in the formerly male-dominated state, and that is one significant temporal change, the essence of state power built on sinews of blood and marriage has undergone little transformation.

What has changed is only the composition of ruling families. In the decades before 1973, the princely and noble families that had historical origins in their bureaucratic services to the absolute monarchs predominated. These families have been outnumbered by commoner-capitalist families in the post-1973 age of bourgeois democracy. These changes, however, have occurred within the shell of patrimonial political culture that nurtures family rule as a whole. Powerholders continue, as ever, to regard their public office as an extension of their households, and try to share it with, or bequeath it to, their clan members, including women. The advent of democracy has not demolished this underlying political culture, which the Nobel laureate Douglass North (Reference North1990, 36–45) categorizes as “informal constraints” on the character of formal state institutions. As a result, the modern “state,” to the extent that it has come into being since 1932, remains distinctively “traditional” in a Weberian sense. One historian (Day Reference Day1996, 386, 404–5) proposes that we conceptualize the “state” in premodern Southeast Asia, including Siam, not as an abstract, reified, and anthropomorphized administrative entity “superstructural to society,” but as the more concrete social process or effect of influential families. This insight applies, with equal validity, to the “state” in post-1932, and especially post-1973, Thailand.

Thailand can therefore be conceptualized as a deep-rooted family-based polity, of which women occupy an increasingly conspicuous part. I do not mean that Thailand has descended into a cohesive, static, and collusive oligarchic polity perennially dominated by the same families or kinship alliances. There is actually enormous variation in the cohesiveness and longevity of political families. The families in power may not be necessarily close to each other; sometimes they are at odds with each other. Some families remain in power for decades, while others fall, only to be replaced by new ones. This is where we can see the dynamics of family rule in Thailand. Few families, except several notable exceptions, have established monopolistic and unchallenged dynastic control over their entire provinces. Thus, Thailand's electoral map displays features of spatially dispersed family rule, whereby a multitude of political families have wielded considerable—but not invincible—influence over their respective constituencies in various provinces at various points in time. Nonetheless, we can view Thai politics as having revolved around elite families as a system, in the sense that the sizeable majority of MPs have been historically recruited from those families. Families remain the locus of power—the name of the political game—in this polity; the uniformity or cohesiveness of this rule is less important than its pervasiveness, ubiquity, and durability as one generic feature of the Thai state. This recurring importance of families has only been accentuated since 1973, thanks to democratization that has brought more women to power.

Some scholars suggest, to the contrary, that family rule is on the ebb or that membership in political dynasties no longer provides a distinctive electoral advantage (Kongkirati Reference Kongkirati2016; Thananithichot and Satidporn Reference Thananithichot and Satidporn2016, 352). One basis for this claim is the growing importance of political parties in the post-Thaksin period. This view holds that as Thailand has become ideologically divided since 2006, joining either a pro-Thaksin or anti-Thaksin party has accordingly become a more important avenue to power than belonging to a political family, especially in the north/northeast and the south. Parties now allegedly trump families at the polls. This view, however, tends to overstate the importance of parties. To the extent that the pro-Thaksin and anti-Thaksin parties have had eminent success in winning seats, it is mainly because they have recruited many candidates from prominent political families, given these candidates' higher chances of electoral success. What lies at the core of these candidates' victories is their family ties and a host of advantages these ties entail; their party affiliations are additional advantages. One might actually argue that the emergence of programmatic parties has helped deepen family rule by enabling various political families to win elections more easily.

In the provinces outside the north/northeast and the south, where ideological polarization is less intense, party affiliations are accordingly less important to most candidates' electoral success. For example, Ponthiwa Nakhasai (b. 1961), wife of an ex-Chainat MP and daughter of the Bangkok-based entertainment mogul who owns the famous massage parlor Poseidon (DBD/MC 1995; NACC 2011e), won the 2007 and 2011 elections without joining a party on either side of the ideological spectrum. The likes of Ponthiwa would have won, regardless of which party they belonged to. Family ties trump party affiliations in these cases.

Another basis for the claim that family rule is petering out is that some prominent political clans have lost parliamentary seats in a few recent elections. A systematic longitudinal analysis of all political families reveals, however, that those families are historical anomalies. It is unwarranted to extrapolate a small ahistorical sample of such cases to a generalization about family rule as a whole. While a handful of well-known political families have recently suffered electoral setbacks, many others have scored (mostly) uninterrupted victories over the decades, sometimes in multiple provinces. Two good examples are the Tienthongs (see above) and the Chidchobs of Buriram Province, a family that has since 1969 produced five MPs including two women—Usanee (senator, 2000–2006) and his sister-in-law, Karuna (constituency MP, 1996–2006). The Prisanananthakul family of Angthong Province, which has produced five MPs since 1986, provides another example.Footnote 14 Even Abhisit Vejjajiva (Bangkok MP, 1992–2001; party-list MP, 2001–14; prime minister, 2009–11), who claims to champion rational-legal governance, is one classic product of deep-seated family rule. His clan has produced Suranant (party-list MP, 2001–6), Prapatpong (Chantaburi MP, 1975–76), and Pongwet (Prapatpong's son; Chantaburi MP, 2001–14) (NACC 2011d, 2011j; Sutabutr Reference Sutabutr1969).Footnote 15 Abhisit is also distantly related, by marriage to his wife, Pimpen, to the Krairerks, a noble clan that has since 1948 produced five MPs for Pitsanulok Province, including a female senator (Pikulkaew) elected in 2006 and 2008 (NACC 2008d; Niyomkul Reference Niyomkul2006, 139). These families are not exceptional. If some of these families no longer have the clout they once had, it still does not diminish the scale of family rule at the aggregate level. The relative decline of some families has only been accompanied by the growing dominance of others; as one family falls, another one rises. Thus, viewed from a longue durée perspective, family rule has stayed resilient without being affected by the changing political fortunes of individual families.

Cast in broader theoretical and comparative perspectives, Thailand, thanks in no small part to the women from political families, has conformed to the famous “iron law of oligarchy” (Michels Reference Michels1949, 377–92), according to which representative democracy inevitably degenerates, over time, into oligarchic rule by a minority of elites. Some other new democracies, including the Philippines (McCoy Reference McCoy1993), Indonesia (Buehler Reference Buehler2007, Reference Buehler2013; Winters Reference Winters2011, 139–93), and Japan (Asako et al. Reference Asako, Iida, Matsubayashi and Ueda2015), have followed similar trajectories. So has even the United States, the world's first state founded on the ideal of democracy (Dal Bó, Dal Bó, and Snyder Reference Dal Bó, Dal Bó and Snyder2009; Domhoff Reference Domhoff1983; Hess Reference Hess2016). In the United States, as in Thailand, women have contributed considerably to oligarchic rule. Of all US congresswomen elected from 1789 to 2000, nearly one-third (31.2 percent) hailed from political families. A comparable figure for congressmen is 8.4 percent (Dal Bó et al. Reference Dal Bó, Dal Bó and Snyder2009, 132).

There are, however, two important interrelated differences in the extent and type of family rule in the United States and Thailand. One is that far more of Thailand's elites have been drawn from political families within a far more compressed time frame. The United States has produced merely 167 political clans in 285 legislative and presidential elections held over 240 years (up to 2014). These families account for only 6 percent of all men and women elected to Congress during the same period (Hess Reference Hess2016, 3). Moreover, the proportion of political families has been decreasing over time (Dal Bó et al. Reference Dal Bó, Dal Bó and Snyder2009, 119). By contrast, the eighteen Lower and Upper House elections held in Thailand since 1975 have seen 591 political families produce 1,072 MPs who constitute 42.8 percent of all 2,502 MPs elected since 1975, and the proportion of political families has been rising. Furthermore, Thailand has more than twice as large a proportion of female MPs from political families (70 percent) as the United States (31.2 percent). The second difference is that if and when any kin (male or female) of former or incumbent politicians seek public office in the United States, they do so because they want to serve the public. In Thailand, many (if not all) candidates' bids for office are motivated by concerns of intrafamily power transfer or sharing.

One reason for these differences lies in the type of political culture in which democratic institutions were first introduced, or the varying degrees to which the rule of law has been established, in the two countries. According to Francis Fukuyama (Reference Fukuyama2015, 199, 208), human beings have natural proclivities for favoring their families. Family rule is therefore “a default mode” of governance. Only the rule of law enforced by the modern state can constrain it. In the case of the United States, it “inherited from Britain a strong rule of law in the form of the Common Law, an institution that was in place throughout the colonies well before the advent of democracy. The rule of law, with its strong protection of private property rights, laid the basis for rapid economic development in the nineteenth century” (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2015, 203; emphasis added). This economic development produced a large, progressive middle class and bourgeoisie that have put the United States on the path of liberal democracy, as predicted by modernization theory. Although clientelism thrived in several big cities in the nineteenth century, the malaise developed after the rule of law had become part and parcel of American political culture. It was not a reflection of patrimonial political culture at large, and it was eventually tamed by the Progressive Era reforms that the new social classes vigorously advocated. Thus, “the sequence by which modern institutions are introduced and, in particular, the stage at which the democratic franchise is first opened,” assumes paramount importance for the type of democracy that is to emerge and take root in a particular country (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2015, 201).

This pattern of development means that political dynasties have emerged in the United States within the institutional context of liberal democracy, which has important implications for the values, norms, and motivations of political family members. If and when a son, daughter, and other kin of a former or incumbent politician runs for office, it is not because they regard public office as their household property that can and should be shared with, or transferred to, the next generation in the way their counterparts in a patrimonial culture do. They have been socialized, since childhood, into drawing a sharp distinction between public and private. Few, if any, are motivated by a sordid desire to reap profits from public office, knowing that there are serious legal consequences of doing so, given the robust and impartial infrastructures of law. They know that capital accumulation is not dependent on political office in the first place. Consequently, only those who have specific and serious policy agendas seek office. Equally important, their candidacies are subjected to critical and unremitting public scrutiny, and family ties hardly guarantee electoral success, as exemplified by Hillary Clinton's unsuccessful bids for the US presidency. Thus, to the extent that political families have emerged in the United States, they are relatively few in number, and they take on less pernicious characters than they do in Thailand.

In Thailand, by contrast, thanks to the century-long absolute monarchy, patrimonialism had become deeply entrenched decades before democratic institutions were transplanted from above in 1932, and it has endured to date. Thailand is still captive to the monarchical past. The rule of law has yet to be established in this historically ingrained culture, which shapes many politicians' views of elected office and their motives for seeking it in negative ways. Only a minority of MPs can be called professional, public-spirited politicians who take their duties seriously, while most others are primarily concerned about dividing political office among their kin. Thus, what I call “patrimonial democracy,” of which elite family rule is one cardinal feature, has transpired.

Unlike in the United States, rapid economic growth in Thailand has only spurred this type of rule, instead of curbing it. This is because Thailand's economy has been fueled mainly by patrimonial practices in the state and business—for example, bank loans, licenses, and other rents dispensed by self-interested elected politicians to their families and other cronies. Thailand's economy has grown because of, not despite, such patrimonial practices. This pattern of growth, while unsustainable in the long run, has demonstrated time and again that political office is the main source of wealth acquisition, protection, and expansion, and has pushed hordes of economic elites and their kin, including women, to seek and hold office in succession. This is how more and more political families have appeared, even though the specific names of families in power may have differed from one election to another.

Thus, Thailand's patrimonial democracy has been quite hospitable to the self-perpetuating cycle of political families' domination. Dal Bó et al. (Reference Dal Bó, Dal Bó and Snyder2009, 116) say “power begets power” about family rule in the United States; it is all the more true in Thailand. The preponderance of female MPs has been a vital component of this cycle. In the final analysis, then, the growing electoral success of women in Thailand does not offer much to rave about, at least for now. It is one manifestation and source of the historical continuity, and even extension, of enduring family-based rule that militates against Thailand's evolution into more pluralistic democracy.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the three reviewers for their helpful suggestions. I am also thankful to Professor Jeffrey Wasserstrom for his encouragement. Douglas Kammen has been a good neighborly sounding board for my ideas, especially those about the United States, while my other colleagues—Irving Johnson, Vatthana Pholsena, and Sorasich Swangsilp—have shared their perspectives on Thai kinship. Kornphanat Tunkeunkunt and Takashi Tsukamoto, both of Thammasat University, rendered invaluable and timely help with tying up several loose ends at various stages. I also thank the library staff at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, for kindly facilitating my research. Financial support for this paper (and the larger book project of which it is a part) has come from two Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 1 grants administered by the National University of Singapore (grant numbers: R-108-000-034-112 and R-108-000-056-112), for which I am grateful.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S002191181700136X.