1. Introduction

Regulatory impact analysis, which analyzes the anticipated effects of proposed regulatory changes, is a key component of the federal regulatory process. Regulatory impact analysis is prescribed by Executive Order 12866, so is required of all agencies whose rules are subject to review by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) (Clinton, Reference Clinton1993). One might expect that given 40 years of practice and OIRA oversight, agencies would be quite competent and relatively uniform in performing regulatory impact analysis. Yet, as Jerry Ellig demonstrated with the Regulatory Report Card that he co-created with Patrick McLaughlin (Ellig, Reference Ellig2016) and associated research (Ellig & McLaughlin, Reference Ellig and McLaughlin2012; Ellig, McLaughlin & Morrall III, Reference Ellig, McLaughlin and Morrall2013; Ellig & Conover, Reference Ellig and Conover2014; Ellig & Fike, Reference Ellig and Fike2016), agencies are highly variable in the quality of their regulatory impact analysis, with some agencies producing good analysis and others whose analysis scored quite poorly.

Until 2018, the Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service (Treasury/IRS) only rarely performed regulatory impact analysis under EO 12866 or submitted rules implementing the Internal Revenue Code for review by OIRA.Footnote 1 A 1983 memorandum of understanding between Treasury and OIRA was interpreted by the Treasury/IRS as exempting most tax regulations from OIRA review (Treasury & OMB, 1983). That arrangement was ratified in 1993 (Katzen, Reference Katzen1993) but changed with a memorandum of agreement (MOA) signed in 2018 that called for both regulatory impact analysis and OIRA review for significant tax regulations (Treasury & OIRA, 2018; Dooling, Reference Dooling2019; Hickman, Reference Hickman2021). In 2023, the pendulum swung in the other direction when the Biden administration not only reversed the 2018 MOA but revoked the OIRA review of tax regulations altogether, without exception (Treasury & OIRA, 2023).

As we wait to see if the pendulum will again reverse direction, we can analyze what happened to Treasury/IRS regulations between the 2018 MOA and the 2023 MOA. Did the quality of the Treasury/IRS regulatory impact analysis improve? As we undertake an empirical study evaluating the OIRA review of Treasury/IRS tax rules, based on regulations published between January 1, 2016, and June 30, 2023, we draw upon the Regulatory Report Card for inspiration and analytical support (Hickman & Dooling, Reference Hickman and Dooling2022; Hickman & Dooling, Reference Hickman and Dooling2024).Footnote 2 This is a project that we hoped to do with Ellig before he passed,Footnote 3 and we miss his expertise greatly.

One might assume that we would find simply that Treasury/IRS regulatory impact analysis matched what was required by the 2018 MOA. However, changes in regulatory practice like those reflected in the 2018 MOA are not self-executing. Institutional change takes time as agencies align their processes to reflect new policy directions. Treasury/IRS would undoubtedly fail a strict application of the Regulatory Report Card prior to the 2018 MOA and would likely fail early in the post-MOA period. Our goal with this project is less about determining whether Treasury/IRS scores particularly well, but whether the Regulatory Report Card offers a way to observe whether and how Treasury/IRS regulatory impact analysis changed over time.

Moreover, the MOA left certain details of its implementation unresolved. In particular, disagreements abound over how benefit–cost analysis (BCA) – one part of regulatory impact analysis – should work in the tax context, lending an element of controversy to the MOA’s implementation (Weisbach, Hemel & Nou, Reference Weisbach, Hemel and Nou2018; Looney & Leiserson, Reference Leiserson and Looney2018; Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020). In this essay, we consider how the principles of regulatory impact analysis and the Regulatory Report Card might apply in the tax context. We take this step in part to address the claims that BCA is not an appropriate tool to assess tax law and policy (Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020). If that is the case, then the Regulatory Report Card, which draws heavily upon BCA, would be an especially poor tool to assess tax regulations. We assert, however, that these critiques often fail to apprehend both the breadth of subject matters addressed by contemporary tax regulations and the extent to which Treasury/IRS exercises policymaking discretion in developing their content, two aspects of modern tax regulation that do lend themselves to BCA.

We begin this essay with a description of the Regulatory Report Card approach for evaluating regulatory impact analysis quality. We then offer a brief typology of tax regulations and the types of questions that they address. Finally, we analyze whether and how regulatory impact analysis should be adjusted for the tax context.

2. The regulatory report card

The Regulatory Report Card project began as a way to measure the quality of regulatory impact analysis (Ellig, Reference Ellig2016). As explained in more detail below, the Regulatory Report Card drew upon the principles of EO 12866 and the Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A-4 (OMB, 2003) to serve as evaluation criteria.Footnote 4 The project focused on proposed rules issued by executive branch agencies that were reviewed by OIRA. Ellig, McLaughlin, and a fleet of trained colleagues evaluated the quality of agency regulatory impact analysis in notices of proposed rulemaking for economically significant “restrictive” regulations issued from 2008 through 2013 (Ellig, Reference Ellig2016).Footnote 5 When the project concluded, it yielded evaluations of 130 proposed “restrictive” rules plus 40 proposed “budget” rules. Writing in 2016, Ellig explained that the motivation for the Regulatory Report Card was to explore whether poor quality analysis was an isolated phenomenon or something that might be related to “political, institutional, and other factors correlated with the quality and use of analysis” which could be the subject of reform.

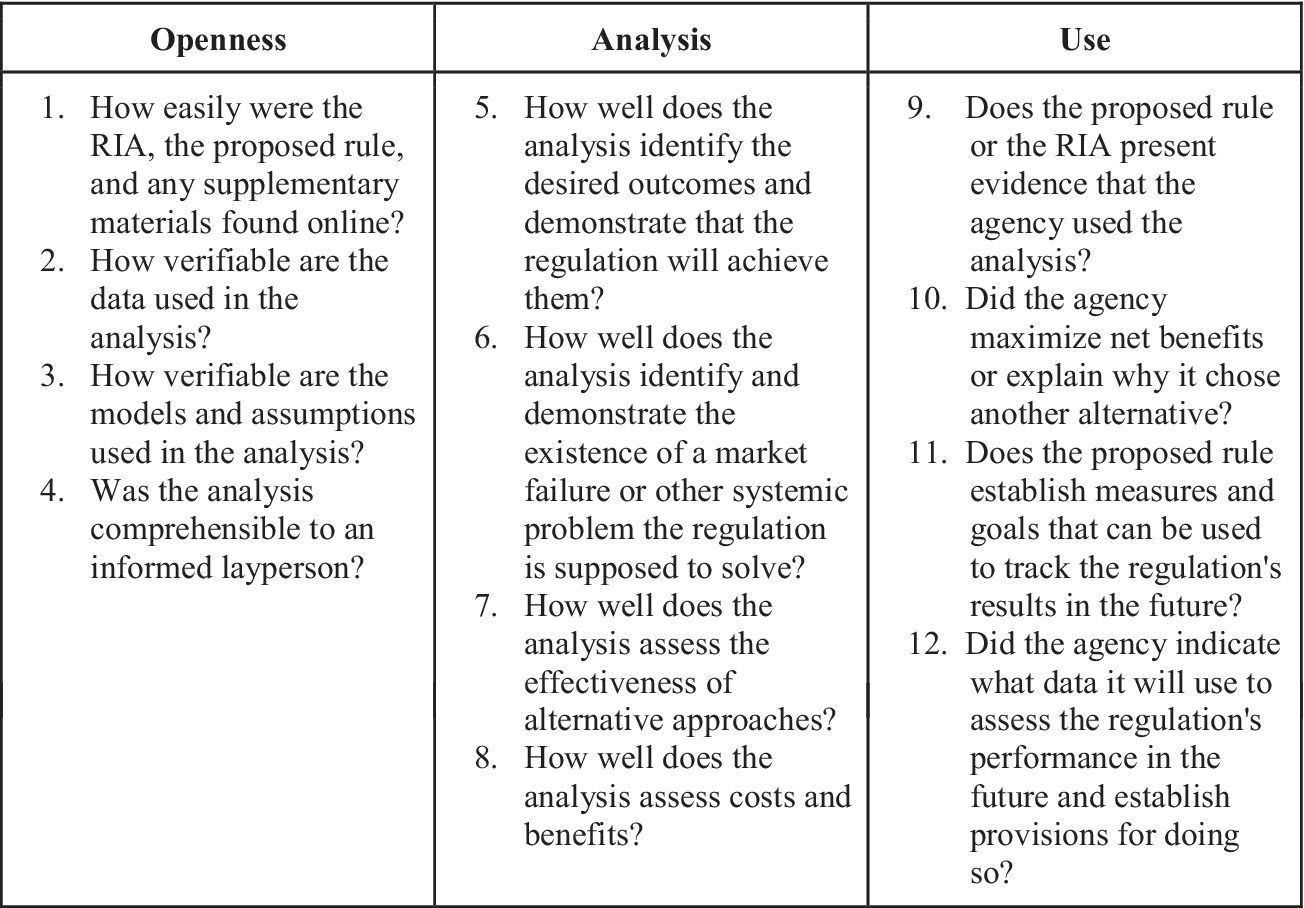

Rather than generate a set of new criteria against which to measure the quality of regulatory impact analyses, Ellig & McLaughlin selected criteria that “flow directly from the principal requirements for regulatory impact analysis found in EO 12866 and OMB Circular A-4” (Ellig, Reference Ellig2016). The Regulatory Report Card is organized into three categories: openness, analysis, and use. Each category has four criteria, as shown in Figure 1.

In addition, each criterion has a list of factors to consider when scoring the analysis. For the analysis criterion, the factors were computed to be a rounded average of scores from a series of subquestions. For example, for the sixth criterion, subquestions included:

-

• Does the analysis identify a market failure or other systemic problem?

-

• Does the analysis outline a coherent and testable theory that explains why the problem (associated with the outcome above) is systemic rather than anecdotal?

-

• Does the analysis present credible empirical support for the theory?

-

• Does the analysis adequately assess uncertainty about the existence and size of the problem?

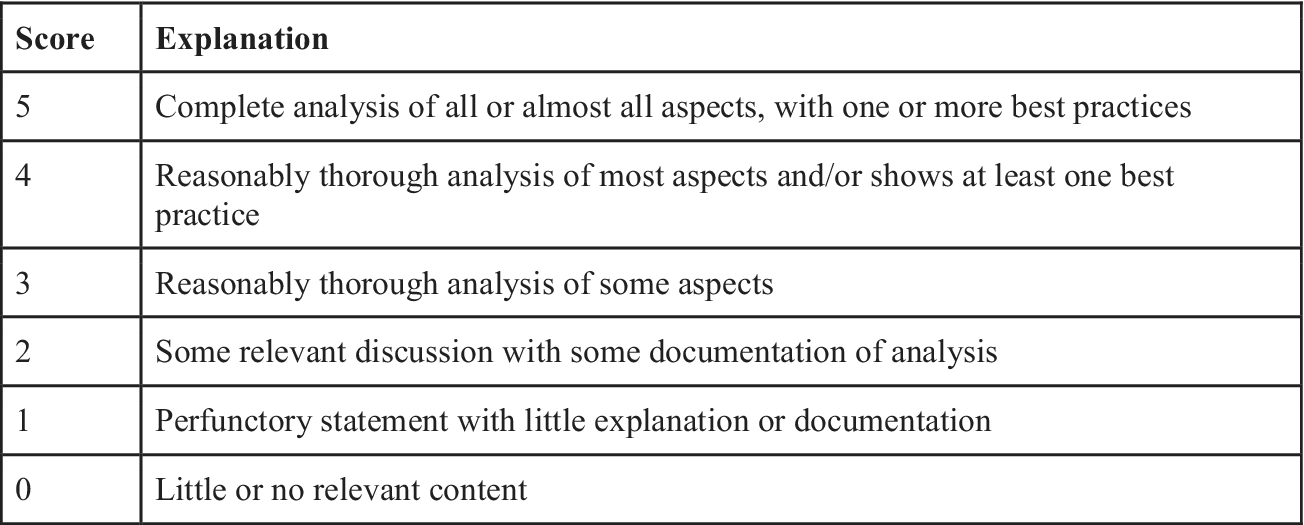

To compile the Regulatory Report Card, assessors scored each factor or subquestion for each proposed rule using a 0–5 Likert scale using the guidance shown in Figure 2. The result was a series of scores for each proposed rule.

Ellig & McLaughlin provided a crosswalk of the scoring criteria and a checklist that OMB issued summarizing the requirements of EO 12866 and Circular A-4 (Ellig & McLaughlin, Reference Ellig and McLaughlin2012). Rather than repeat that comprehensive crosswalk here, we offer a few examples to show the close relationship between the Regulatory Report Card criteria and EO 12866 and Circular A-4. For example, EO 12866 directs agencies to “identify the problem that it intends to address (including, where applicable, the failures of private markets or public institutions that warrant new agency action) as well as assess the significance of that problem.” This corresponds to criterion 6 in the Regulatory Report Card, shown above in Figure 1. Similarly, EO 12866 directs agencies to “assess both the costs and the benefits of the intended regulation and, recognizing that some costs and benefits are difficult to quantify, propose or adopt a regulation only upon a reasoned determination that the benefits of the intended regulation justify its costs.” Circular A-4 provides detailed guidance to agencies on how to conduct this analysis, which maps to criteria 7 and 8. In short, the Regulatory Report Card gauges the extent to which agencies are adhering to the direction of EO 12866 and Circular A-4. While reasonable people can disagree over the meaning of the “quality” of regulations or regulatory analysis, the Regulatory Report Card is an undeniably useful tool to evaluate agency responsiveness to EO 12866 and Circular A-4.

3. Regulatory impact analysis outside the tax context

Before turning to tax regulations, we offer some explanations and examples of how the “Analysis” criteria of the Regulatory Report Card apply in the nontax context.Footnote 6 While practitioners of regulatory BCA will be very familiar with these ideas, we sketch them here for other readers, particularly those from the tax community, who may be less familiar with this language and how it applies to the nontax regulatory context. This sets the stage for us to describe how these concepts apply in the tax context in Parts 4 and 5 below.

3.1. Explaining the need for federal regulatory action

EO 12866 directs that the federal government “should promulgate only such regulations as are required by law, are necessary to interpret the law, or are made necessary by compelling public need, such as material failures of private markets to protect or improve the health and safety of the public, the environment, or the well-being of the American people.” An agency’s regulatory impact analysis, therefore, should begin with an explanation of how it meets this threshold.

Circular A-4 fills in certain technical details. For example, it lists among the common reasons for regulation the need to correct market failures, “which may implicate externalities, common property resources, public goods, club goods, market power, and imperfect or asymmetric information” (OMB, 2023). These market failures are grounded in microeconomic theory, but they do not limit the government’s ability to regulate. Instead, Circular A-4 goes on to identify other reasons for regulation, including improving the functioning of government, removing distributional unfairness, or promoting privacy and personal freedom (OMB, 2023). In this way, Circular A-4 accounts for a wide range of regulatory activity and preferences.

For some, it may seem obvious that, if the government is proposing a rule, then it has a good reason. Others might be more skeptical of the government’s reasons. No matter how one approaches the regulatory enterprise in general, requiring an agency to write down what it is trying to achieve with a regulation should not be controversial.Footnote 7 Sometimes, an agency’s regulatory goals can get out of sync with a regulation’s likely effects. The opportunity to flag such a disconnect is one reason among many why this first step is important (Dudley et al., Reference Dudley, Belzer, Blomquist, Brennan, Carrigan, Cordes, Cox, Fraas, Graham, Gray, Hammitt, Krutilla, Linquiti, Lutter, Mannix, Shapiro, Anne Smith and Zerbe2017).

Consider, for example, a regulation that tries to make cars safer by adding mandatory safety features. At some point, adding more safety features makes new, ultra-safe cars so expensive that most people cannot afford them. Instead, people may choose to keep their less-safe cars longer rather than upgrade to a newer, safer car sooner. If the regulatory goal is to improve safety, but very few of the vehicles are likely to be sold due to the increased cost, then the regulatory design frustrates the regulatory goal. If the regulation’s drafters skip the first step of articulating the regulation’s goal, the focus of the regulatory process may drift to how elaborate or impressive the safety features are, or how many lives they might save if cost were no object, without regard to whether real people will be able to access them. Expecting an agency to express the problem it is trying to solve or the goal it is trying to achieve helps keep the attention of regulation drafters on the relationship between goals and means. As noted in Part 3.3 below, this first step is also helpful in determining how to draw lines between benefits, costs, and transfers.

3.2. Consideration of alternatives

Contemporaneous explanations of an agency’s reasons for acting additionally become very useful later in the process of regulatory impact analysis when an agency weighs alternatives. EO 12866 directs that “[i]n deciding whether and how to regulate, agencies should assess all costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives, including the alternative of not regulating.” Before we turn to benefits and costs, some exploration is warranted of the role that alternatives play in regulatory impact analysis.

Circular A-4 offers some ideas for the types of alternatives that an agency might consider analyzing, such as differing degrees of stringency, different compliance timeframes, and altering the regulation based on geographic considerations. EO 12866 and Circular A-4 encourage agencies to analyze at least three alternatives. Circular A-4 explains, “[t]he number and choice of alternatives selected for detailed analysis is a matter of judgment. There must be some balance between thoroughness and practical limits, such as the limits on your analytical capacity. With this qualification in mind, it is generally informative to explore modifications of some or all of a regulation’s key individual attributes or provisions to identify appropriate alternatives” (OMB, 2023). In theory, any complex rule could have dozens, if not hundreds, of potential alternatives, so this guidance from Circular A-4 clarifies that the agency’s judgment is critical to choosing a sensible range of alternatives to evaluate.

Parsing out alternatives gives an agency a foundation for its regulatory impact analysis. For example, a new reporting requirement for farms could be filed on an annual, semi-annual, quarterly, or monthly basis. Each of these options will come with varying considerations that an agency could analyze. Perhaps more frequent reporting is more expensive for the farms but seems worth it because the problem that the agency is trying to solve is time-sensitive. Or, the agency might only analyze the data once per year, suggesting that annual reporting might be sufficient. Identifying regulatory alternatives, therefore, offers a method for articulating and balancing the kinds of competing concerns that are baked into so many regulatory choices but which might otherwise be obscured or unexamined.

Analysis of regulatory alternatives also relates to the idea of legal discretion. Regulatory authority flows to an agency from acts of Congress. Sometimes, Congress constrains an agency’s regulatory authority so that the agency lacks any discretion and merely uses a regulation to move statutory text into the Code of Federal Regulations. In most instances, however, the agency makes choices when it promulgates a rule. Analyzing the alternatives offers one way for agencies to identify and justify the regulatory choices they are making.

3.3. Analysis of regulatory consequences – benefits, costs, and transfers

With these threshold matters established, we are ready to consider the consequences of proposed regulatory changes. It is easy to get tangled up in arguments about what qualifies as a “benefit” or a “cost.” As we will discuss more below, this is a core objection to the use of BCA in the tax context (Leiserson & Looney, Reference Leiserson and Looney2018; Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020). More generally, it is reasonable to think that one person might perceive a proposed change to be a benefit while another might view it as a cost.

Economists acknowledge and navigate around this concern with a series of choices that make it easier to sort consequences into the correct column for BCA. For example, in its influential 2016 RIA Guidance, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services explains that “[a]nalysts should comprehensively consider all potentially important consequences, including both those that are intended and unintended (positive or negative).” This framing helps get all consequences on the board. The Guidance goes on to explain that benefits “should relate to the intended outcomes of the regulation; i.e., the welfare improvements that comprise its goals,” while costs “should relate to the investment or inputs needed to achieve those outcomes.” While others might define these terms differently, this general approach helps explain why the first step above – articulating what the rule is trying to achieve – is so important, in part because the rest of the analysis uses it to help sort the various and often complex consequences of a proposed regulatory change.

While BCA strives for monetization of benefits and costs, both EO 12866 and Circular A-4 readily concede that important consequences of regulatory choices can be difficult to quantify. Where this is the case, Circular A-4 directs analysts to “exercise professional judgment in identifying the importance of unquantified factors and assess, as best you can, how they might change the ranking of alternatives based on estimated net benefits” (OMB, 2023). This is a clear indication that BCA permits the consideration of unquantified consequences, but it does put the onus on the agency to articulate and explain those consequences to a reasonable degree.

For purposes of BCA, transfers are “monetary payments between persons or groups that do not affect the total resources available to society” (HHS Guidelines, 2016). Transfers are categorized differently from benefits and costs because they would otherwise show up on both sides of the conceptual ledger in equal magnitude. If the Medicare program increases the payment rate for a particular surgical procedure, the funds to cover that increased rate come from some combination of taxpayers and reductions in payments to other providers. Because these amounts net out, they are set aside for BCA purposes. If the actions characterized as transfers lead to significant behavioral changes, as many do, those downstream behavioral changes are analyzed separately in the BCA as benefits or costs, respectively. If the increased surgical reimbursement rate leads to a meaningful increase in the number of life-saving procedures and therefore lives saved, for example, that would be discussed as part of the benefits.

4. Tax rule typology

Obviously, a key function of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is to raise revenue for the federal government through the imposition of various taxes, including but not limited to individual and corporate income taxes as well as payroll taxes like social security and Medicare taxes. On the other hand, raising revenue is not the only, or even necessarily the primary, focus of all provisions in the IRC or tax regulations. Congress increasingly uses the IRC as its preferred vehicle for incentivizing or discouraging certain activities or for pursuing other regulatory and social welfare goals (Tahk, Reference Tahk2013; Hickman, Reference Hickman2014). According to one study, roughly 30–40% of tax regulatory actions from 2008 through 2012 were more closely associated with social welfare and regulatory goals, while another 15–20% of tax regulatory actions concerned matters of tax administration and procedure (Hickman, Reference Hickman2014).

Consequently, just as nontax rules address and serve a broad range of problems and goals, tax regulations are highly variable as well. At first impression, some tax regulations lend themselves more readily to both regulatory impact analysis and the Regulatory Report Card than others. First impressions can be misleading. Regardless, any consideration of the Regulatory Report Card in the tax context requires some appreciation for the different forms and functions of tax regulations.

4.1. “Traditional Tax” regulations

Many regulations issued in service of the IRC’s traditional revenue-raising function are definitional, much like the statutory provisions they implement and interpret. For example, the income tax is imposed by taxing net income at statutorily specified rates (IRC § 1). Defining net income requires defining, in turn, what inflows or accruals count as gross income, what expenditures incurred in the course of earning that income should be accepted as offsets to gross income, and the timing for recognizing each, among other questions.

Treasury/IRS likes to claim that the statute resolves all the key questions and Treasury/IRS regulations merely “provide a mechanism for the tax to be satisfied or collected” (Internal Revenue Manual § 32.1.5.4.7.4.3(5)). Yet, there is no doubt that the Treasury/IRS enjoys a tremendous amount of interpretive latitude and policymaking discretion in the regulations it adopts. Examples abound, but a particularly illustrative one concerns the provisions governing the capitalization and depreciation of capital assets.

Business expenditures generally are deductible as an offset to gross income (IRC § 162). When a business or other income-generating enterprise buys or improves an asset that will aid the production of income for a long period of time, like a building or a large piece of manufacturing equipment, the IRC generally does not allow an immediate deduction for the cost (IRC § 263(a)). Instead, that cost must be capitalized and deducted as an offset to gross income over a period of years, as the asset is used up and correspondingly depreciates (e.g., IRC §§ 167 & 168).Footnote 8 The statute offers very little guidance regarding which expenditures must be capitalized. All of the details are in the many, many pages of regulations distinguishing capital expenditures from supplies or maintenance, categorizing types of capital expenditures, addressing depreciation methods, providing de minimis exceptions, and so forth (e.g., Treas. Reg. §§ 1.162–3; 1.162–4; 1.263(a)–1; 1.263(a)–2; 1.263(a)–3; 1.263(a)–4; 1.263(a)–5; 1.263(a)–6). In a sense, all of these regulations are merely definitional, drawing the boundaries on the different categories leading to the computation of net income. Yet, how all of these questions get resolved can incentivize or disincentivize whether such expenditures occur in the first place, with enormous economic and other policy implications (Batchelder, Reference Batchelder2017).

4.2. Social welfare and regulatory provisions, including tax expenditures

Many longstanding features of the IRC deliberately pursue social welfare or regulatory goals in the course of raising revenue, starting with the progressive rate structure of the individual income tax. In many instances, however, provisions that contribute to defining net income or determining the amount of income taxes owed bear at best a tangential relationship to any conceptual theory of income taxation. Instead, these provisions are aimed deliberately at shaping taxpayer behavior to achieve other goals. For example, the IRC provides income tax credits for adoption expenses (IRC § 23) and energy-efficient improvements to personal homes (IRC § 25D), and it denies income tax deductions for bribes (IRC §162(c)), political lobbying (IRC § 162(e)), and excessive executive compensation (IRC § 162(m)), all for the purpose of encouraging the former and discouraging the latter, rather than to serve goals more directly associated with the tax system’s revenue collection function.

Recent decades have seen a dramatic escalation in tax programs and provisions serving purposes other than traditional revenue raising (Hickman, Reference Hickman2014). Congress has expanded its use of tax expenditures in the form of exclusions, deductions, credits, deferrals, and preferences, rather than direct spending, to achieve social welfare and regulatory policy goals. For fiscal years 2019 through 2023, the Joint Committee on Taxation has identified more than 250 separate tax expenditure items across 17 different categories – e.g., Energy; Agriculture; Transportation; Health; Community and Regional Development; and Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services – averaging more than $1.6 trillion per year (Joint Committee on Taxation, 2019). Treasury/IRS is at least one of the most significant, if not the most significant, among federal government agencies administering anti-poverty programs (Weisbach & Nussim, Reference Weisbach and Nussim2004; Zelenak, Reference Zelenak2005).Footnote 9

Many of these tax expenditure items have translated into extensive regulations that, in turn, reflect innumerable policy choices. Consider, for example, Treasury/IRS’s extensive regulation of the exempt organization sector. The IRC exempts a few dozen statutory classifications of entities from the corporate income tax: educational institutions ranging from large research universities to tiny religious schools with a few dozen students; large hospitals and small, free health clinics; labor unions; chambers of commerce; churches big and small; the Metropolitan Opera and tiny, rural theater companies; and the local Elks Lodge, for just a few examples (IRC § 501(c); Fishman, Reference Fishman2006). The IRC also provides a deduction for individual contributions to certain charities (IRC § 170). Neither the exemption from the corporate income tax nor the deduction for charitable contributions contributes to revenue raising in any way; rather, both are means by which the federal government indirectly subsidizes exempt organizations and, as a consequence, lowers tax revenue. These subsidies come with strings, however, as the IRC dictates lengthy eligibility criteria for both exempt status and deductibility; the activities in which exempt organizations may or may not engage; the types of income that exempt organizations can earn, and the consequences of earning other types of income; nondiscrimination requirements; reporting requirements; and prohibitions on private inurement and quid pro quo, among other matters. Yet here again, a few dozen pages of statutory provisions have yielded a few hundred pages of regulations as the Treasury/IRS fill in many undefined details with new standards, safe harbors, de minimis rules, and other discretionary choices with substantial implications for free speech, politics and religion (Mayer, Reference Mayer2019); election law and campaign finance (Mayer, Reference Mayer2011); and health policy and hospital governance (Berg, Reference Berg2010), among other nontax issues.

4.3. Administrative regulations

The complexity of the IRC and the federal tax system makes administration and enforcement a challenge. Many provisions in the statute itself are aimed at supporting those functions. Many more regulations implement and interpret those provisions, again with the Treasury/IRS exercising significant policymaking discretion with real-world consequences for private parties. These provisions rarely alter anyone’s underlying tax liability. Rather, they more typically provide tools to facilitate the smooth function of the tax system – i.e., to “improve the day-to-day functioning of government,” in Circular A-4 terms (OMB, 2023). Failing to comply with the requirements these provisions impose can lead to penalties for noncompliance.

One example of Treasury/IRS administrative regulations is third-party information reporting requirements. Such requirements abound in the IRC. For example, employers must report the wages paid to their employees (IRC § 6041). Corporations must report the dividends paid to their shareholders (IRC § 6042). Mortgage lenders must report the interest received from borrowers (IRC § 6050H). Not all of these reporting requirements include extensive regulations elaborating their scope, content, and other details, but some do. For example, the regulations at issue in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury, 799 F.3d 1065 (D.C. Cir. 2015), imposed a new reporting requirement on U.S. banks for interest paid to certain foreign account-holders under IRC § 6049 (26 C.F.R. §§ 1.6049–4, 1.6049–8). Regulations under IRC §§ 6111 and 6112 requiring “material advisers” to track and report “reportable transactions” (i.e., tax shelters) undertaken by their clients, and under IRC §§ 6707, 6707A, and 6708 establishing parameters for associated penalties for failing to comply with those requirements, are particularly extensive and onerous (e.g., 26 C.F.R. §§ 301.6111–3, 301.6112–1, 301.6707–1, 301.6707A–1, 301.6708–1).

From the government’s perspective, third-party information reporting is an extraordinarily effective and efficient way to ensure that people are reporting items on their tax returns truthfully, and thus paying the taxes they owe. Information reporting is helpful to taxpayers as well, reducing their recordkeeping burdens and making it easier to prepare and file tax returns (Lederman, Reference Lederman2010; Kleven, Kreiner & Saez, Reference Kleven, Kreiner and Saez2016). The information reporting regulations at stake in Florida Bankers served an additional purpose of giving Treasury/IRS information that it could provide foreign governments in exchange for tax information regarding the activities of U.S. taxpayers outside the U.S. However, third-party information reporting is not costless, and regulations that make discretionary choices expanding the burdens of third-party reporting increase those costs.

Another type of administrative regulation by Treasury/IRS concerns the qualifications and conduct of professionals who represent clients in tax matters before the agency. For example, section 330 of Title 31 of the United States Code authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to “regulate the practice of representatives of persons before” it. Treasury/IRS has relied on this authority to adopt extensive regulations imposing various duties and restrictions on a wide array of professionals who represent taxpayers before the IRS, as well as establishing sanctions and disciplinary proceedings for those professionals who fail to comply with those duties and restrictions (31 C.F.R. Part 10). In Loving v. IRS, 742 F.3d 1013 (D.C. Cir. 2014), the D.C. Circuit rejected as beyond statutory authority regulations in which Treasury/IRS sought to extend that regime to a new group of tax return preparers who also were required by the regulations to register with the IRS, pay annual fees, pass an entrance exam, and satisfy continuing education requirements.

5. Tax-specific adjustments to the regulatory report card

In this section, we consider how regulatory impact analysis concepts, and therefore aspects of the Regulatory Report Card, apply in the tax context. We do this in part because the Regulatory Report Card project did not include any tax regulations from the Treasury/IRS and also because of criticism arguing that BCA is “fundamentally ill-suited” to tax (Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020). Core critiques are that BCA “ignores” revenue effects by relegating them to the transfer category, focuses on efficiency to the exclusion of the many distributional considerations inherent in tax policy, and generally does not provide enough useful information to be worth the effort needed to produce it (Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020).Footnote 10 If it is true that BCA is not a good fit for tax regulations, that conclusion would diminish the value of the Regulatory Report Card as an evaluative tool.Footnote 11

Another common critique of BCA is that it relies too much on quantitative estimates, while many regulatory effects may not lend themselves to that treatment. Section 6 of EO 12866 describes the benefits to be considered as including, “but not limited to, the promotion of efficient functioning of the economy and private markets, the enhancement of health and safety, the protection of the natural environment, and the elimination or reduction of discrimination or bias,” irrespective of whether those benefits are quantifiable. That same section correspondingly includes among the costs to be assessed in regulatory impact analysis not only “the direct cost both to the government in administering the regulation and to businesses and others in complying with the regulation,” but also “any adverse effects on the efficient functioning of the economy, private markets…, health, safety, and the natural environment,” again irrespective of whether those costs can be quantified. Finally, regulatory impact analysis as defined by EO 12866 includes an assessment of the “costs and benefits of potentially effective and reasonable feasible alternatives to the planned regulation … and an explanation why the planned regulatory action is preferable to the identified potential alternatives.” In short, regulatory impact analysis is qualitative as well as quantitative, reflecting a goal of providing a framework for reasoned decision-making, rather than merely an assessment of the least costly regulatory approach in terms of dollars and cents (Hickman, Reference Hickman2021).

With this understanding of regulatory impact analysis as flexible and qualitative as well as quantitative, we think it is valuable to contemplate whether and how tax regulations may merit tax-specific accommodations or adjustments when it comes to regulatory impact analysis in general and BCA in particular. To that end, we structure this section to mirror the examples of tax regulations described above, to consider how the various analytical steps described above in Part 2 – and which are themselves reflected in the Regulatory Report Card – play out for these kinds of tax regulations.

5.1. “Traditional Tax” regulations

The definitional tax regulations described above are analogous to many nontax regulations. Many government programs use definitions to describe who will qualify for benefits or exemptions, for example. Many statutes establishing benefits programs rely on undefined or underdefined statutory terms, anticipating that agency regulations will add definitions that, in turn, will limit or expand the scope of eligibility criteria. While agencies might draw these lines merely to be able to administer the program in question, intended and unintended consequences flow from those definitions. As noted above, the “problem” step, explored in criterion 5 of the Regulatory Report Card, can be especially illuminating for definitional regulations. If the purpose of regulation is to detail the circumstances in which benefits may not be received, drawing those definitional lines immediately creates incentives to adjust behavior to obtain the benefits. The process of writing down the goal of a regulation helps provide a standard against which the likely consequences of that regulation can be measured and considered.

In the tax context, sometimes the government’s goal is less easily understood as being in response to a “problem” and more about simply implementing and administering the tax system. If so, an analysis that reveals both the intended and unintended consequences of a proposed regulation can help decision-makers and the public think through the incentives created by a definitional tax regulation to assess whether those incentives – and their likely consequences – are acceptable. To omit this analysis or argue that it is not appropriate is to suggest that definitional choices do not have consequences outside of helping people determine how, for example, to file their taxes. Ignoring the fact that definitional and other, similar choices can have a domino effect does not make it less true. A proposed regulation that fails to share this information with the public misses an opportunity to justify agency choices in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act (Hickman, Reference Hickman2021).

Turning to the Regulatory Report Card, the subquestions for criterion 6 (“How well does the analysis identify and demonstrate the existence of a market failure or other systemic problem the regulation is supposed to solve?”), in the bulleted list above in Part 2, are an uneasy fit for those rules that have a primary goal of raising revenue. For example, if Treasury regulations are aimed simply at resolving definitional ambiguity regarding items of income, then asking the Treasury/IRS to justify the regulation by reference to a market failure or other systemic problem and to provide empirical support for the existence of that ambiguity seems inappropriate. On the other hand, when the government’s goals include nontax social or regulatory objectives, which we discuss more below, these subquestions are more probative. Because of this variation, for purposes of our study, we may assign a score for criterion 6, but not the individual subquestions, because we think scoring the individual subquestions will lead to lower scores than are reasonable.Footnote 12

5.2. Social welfare and regulatory provisions, including tax expenditures

In this category, the goal of the tax regulation is less about raising revenue and more about incentivizing behavioral change. In this context, the treatment of related revenue effects deserves special attention. BCA uses the transfer concept described above to describe those effects that largely cancel out across benefit and cost categories. The Child Tax Credit is not the subject of extensive regulations, but it helps explain this concept. Funds to recipients can be understood as benefiting society as well as individuals, offset by the cost to taxpayers. Categorizing such credits and the associated tax revenues that fund them as transfers is a way to acknowledge that they wash out; you cannot have one without the other because they redistribute funds. That redistribution, of course, is critical to consider, and the analyses conducted by the Joint Committee on Taxation and Treasury pay close attention to these effects using analytical tools that differ from BCA. Distributional analysis – the subject of early regulatory policy direction to OIRA from the Biden administration (Biden, Reference Biden2021) – and BCA can function in a complementary manner, providing different information to decision-makers and the public.

Criticism that BCA “relegate[s] to second-tier status” and ignores revenue effects (Leiserson, Reference Leiserson2020) seems to take this analytical choice as a slight. But BCA simply offers complementary information to complete the analytical picture. For example, the downstream behavioral effects of regulatory choices in tax may well be swamped by the revenue effects. Parsing out behavior change, particularly for those regulations that are intended to spur behavior change, – e.g., increased adoptions, purchases of solar panels, or charitable contributions – helps shine a light on those effects in a way that focusing exclusively on revenue effects would obscure. Working within the BCA framework is not in tension with a robust acknowledgment that the tax system provides benefits to society by funding government programs and redistributing wealth. Our understanding is that, as a technical matter, BCA does recognize revenue expenditures as benefits, but it also includes a reciprocal recognition of the offsetting costs to taxpayers, which causes these two effects to net out. To keep the analysis organized, BCA moves effects like this into the “transfers” category.

Distributional analysis, however, offers a place to explore the consequences of particular proposed redistributions. One of the bargains struck in the 2018 MOA was to adjust the significance test for economically significant tax regulations to exclude revenue effects (Dooling, Reference Dooling2019). If that test had not been adjusted from the usual $100 million threshold, even minor tax regulations might have triggered OIRA review. The choice to remove revenue effects from this threshold decision – which determines which rules Treasury/IRS submits for OIRA review in the first place – does not require excluding these effects from the agency’s regulatory impact analysis. Instead, it would be appropriate to use distributional analysis – which is part of an agency’s regulatory impact analysis – to provide detailed information about how proposed tax regulations would affect differently situated individuals and organizations.

These questions about how to categorize various regulatory effects in the tax context are tricky and likely will continue to be the subject of debate (Weisbach, Hemel & Nou, Reference Weisbach, Hemel and Nou2018; Leiserson & Looney, Reference Leiserson and Looney2018). For purposes of our project, we note that the Regulatory Report Card generally asks whether agencies “show their work.” We, similarly, plan to give “credit” for evidence in regulatory preambles of any economic analysis, including distributional analysis, irrespective of whether the analytical methods are novel (Weisbach, Hemel & Nou, Reference Weisbach, Hemel and Nou2018) or more traditional. We think this is a reasonable way to acknowledge that the field is in flux, methods are likely to evolve, and Treasury/IRS should be commended for trying new analytical approaches and sharing them with the public in regulatory preambles.

5.3. Administrative regulations

The third-party reporting requirements described above regulate the conduct of non-government parties. While third-party reporting requirements in the tax context support the revenue-raising function, they also are distinct from it. Other, nontax regulatory activity is often similar, as for example, the Nutrition Facts Panel, which is governed by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules at 21 CFR Part 101. In this context, the compulsory information flow goes from the manufacturer to the public, but the regulatory mechanism of requiring an entity to disclose information is analogous. Analyzing alternative formulations of such required disclosures is typical for other agencies, and it may be especially helpful to balance the burdens imposed by the reporting requirements with the government’s need for the right information at the right time. Such information also fits squarely under the Paperwork Reduction Act analysis that is often presented alongside the regulatory impact analysis in a proposed regulation.

Treasury/IRS regulations that impose requirements for professional practice before the IRS likewise have nontax analogues. In short, these types of regulations have little or no revenue effect, so a tax-specific objection to the use of BCA does not follow. They should be a good fit for regulatory impact analysis. While we are open to the idea that some tax regulations in this category might raise novel concerns that require special handling, the two examples here are sufficiently analogous that we do not see a reason to take a special approach to their analysis.

6. Conclusions

Because the 2018 MOA was in place for several years before it was revoked in 2023, the time is right to assess how and whether the 2018 MOA influenced Treasury/IRS tax regulations. As part of our methodology, we draw upon the Regulatory Report Card to help us evaluate the extent to which the 2018 MOA altered the Treasury/IRS’ regulatory impact analysis of tax regulations. The Regulatory Report Card offers a coherent approach to observing incremental changes to elements of regulatory impact analysis that might otherwise be difficult to parse. Institutional change is challenging, and we think it is important to give credit where it is due. A close read of Treasury/IRS tax regulations, facilitated in part by the Regulatory Report Card, will allow us to assess not just the period of time when the 2018 MOA was in effect, but also to provide insights to inform future reforms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joe Cordes, Susan Dudley, Daniel Hemel, Patrick McLaughlin, Sean Mulholland, and participants and audience members at the Jerry Ellig Memorial Conference for helpful comments and conversations.