Introduction

Depression is one of the most common health disorders worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 300 million people suffer from it globally. The most tragic manifestation of long-lasting moderate or severe depression is suicide, which kills about 800,000 people annually (WHO 2018a).

Eastern Europe, including Lithuania and Russia, is one of the regions with the highest rates of depression and years of lives lived with disability (YLD) (Ferrari et al., Reference Ferrari, Charlson, Norman, Patten, Freedman and Murray2013). Moreover, these countries have some of the highest suicide rates in the world (WHO, 2018b).

Depression occurs as a result of a complex interaction of psychological, social and biological factors. People who have experienced an adverse event such as job loss, bereavement, psychological trauma or maladaptation are more likely to develop depression. Depression, in turn, can increase stress, disrupt normal vital activity, worsen the life situation of a person suffering from it and lead to even more severe depression (Pillay & Sargent, Reference Pillay and Sargent1999; Saarijarvi et al., Reference Saarijarvi, Salminen and Toikka2001; Sakurai & Inoue, Reference Sakurai and Inoue2018; Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Isometsa, Sund and Pirkola2019; Bhattachacharya et al., Reference Bhattachacharya, Camacho, Kimberly and Lukens2019; Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Gary, O’Malley, Hamilton and Shulenberg2019).

Factors that are undoubtedly associated with health status are some anthropometrical indices, such as body mass index (BMI). A high BMI, indicating overweight or obesity, especially at a younger age, is a key risk factor for type II diabetes and arterial hypertension (Gregg & Shaw, Reference Gregg and Shaw2017). Attempts to explain the mechanisms underlying the associations between depression and anthropometrical indices have focused on psychological and biological factors. Stevens et al. (Reference Stevens, Herbozo and Martinez2018) found that individuals with highly negative weight-based attitudes and high BMI values showed high levels of depressive symptoms and reported a strong negative impact of negative weight or shape commentary. Other studies found associations between depression, BMI and third factors, such as low socioeconomic status (Vittengl, Reference Vittengl2019) and vitamin D deficiency (Jani et al., Reference Jani, Knight-Agarwal, Bloom and Takito2020). There have also been attempts to find genetic factors responsible for the associations between depression and anthropometrical indices. For example, Rivera and colleagues have explored the impact of different genes on depression and BMI. A meta-analysis has provided support for a significant interaction between the FTO gene, depression and BMI, indicating that depression increases the effect of FTO on BMI (Rivera et al., Reference Rivera, Locke, Corre, Czamara, Wolf and Ching-Lopez2017a). Another study by the same group did not support the implication of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in the genetic relationship between BMI and major depression (Rivera et al., Reference Rivera, Rovira, Cervilla, Ching-López, Martín-Laguna and Bandrés-Ciga2017b).

Numerous studies have suggested positive associations between the risk for depressive disorders and BMI (Bjerkeset et al. Reference Bjerkeset, Romundstad, Evans and Gunnell2007; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Salas, Tabet, Kasper, Elder, Staley and Brownson2017; Rivera et al. Reference Rivera, Rovira, Cervilla, Ching-López, Martín-Laguna and Bandrés-Ciga2017b; Assari et al. Reference Assari, Caldwell and Zimmerman2018; Tyrrell et al., Reference Tyrrell, Mulugeta, Wood, Zhou, Beaumont and Tuke2019), total body weight (Vittengl, Reference Vittengl2019) or fat mass (Speed et al., Reference Speed, Jefsen, Boerglum, Speed and Oestergaard2019). However, Hinnouho and colleagues have reported that poor metabolic health, irrespective of BMI, is associated with greater depressive symptoms (Hinnouho et al., Reference Hinnouho, Singh-Manoux, Gueguen, Matta, Lemogne and Goldberg2017). Height also reflects health status, risk of certain diseases and quality of life. The common tendency to associate taller stature with physical attractiveness, authority, leadership, higher cognitive function and social and professional success leads to the perception that, in the realm of human growth, similar to economic growth, bigger is better (Bartke, Reference Bartke2012). For example, shorter people appear to experience an increased risk of coronary heart disease. However, some types of cancers are more common in taller people (Batty et al., Reference Batty, Shipley, Gunnell, Huxley, Kivimaki and Woodward2009). As for associations between depression and height, the findings of different studies are scarce and controversial: some authors suggest that height (short stature) is a causal risk factor for depression (Speed et al., Reference Speed, Jefsen, Boerglum, Speed and Oestergaard2019), whereas others disagree (Bjerkeset et al., Reference Bjerkeset, Romundstad, Evans and Gunnell2007; Vittengl, Reference Vittengl2019).

The aim of this study was to investigate possible associations between depression, height and BMI in the adolescent and adult population of Penza city and oblast, Russia.

Methods

The study data were derived from a questionnaire completed by 554 participants in a survey conducted in Penza city and oblast (an administrative division, literally meaning ‘area’, ‘province’ or ‘region’) of the Russian Federation. The age range of the participants was 16–89 years. Participants included students of the Penza College of Architecture and Construction (16–23 years old), civil servants of Nikolsky district, Penza oblast, labourers of the Penza precision instrument factory and JSC ‘Electropribor’ (24–59 years old) and retirees (60–89 years old).

The methodological basis for the assessment of depression was A. Beck’s concept of ‘cognitive vulnerability’, which describes two levels of cognitive processes in depression: superficial and deep (Beck, Reference Beck1987, Reference Beck2008). The presence and severity of depression was evaluated using Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996).

The participants self-reported their height (cm) and weight (kg), and their BMI was calculated (weight (kg)/height (m)2). In adults, thinness was defined as BMI <18.5 kg/m2, overweight as BMI>25 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI >30 kg/m2. In adolescents, thinness, overweight and obesity were defined according to IOTF cut-off values (Cole & Lobstein, Reference Cole and Lobstein2012).

The data were checked for normality and only non-parametrical tests were applied. Since initial analysis indicated no linear relationship between the analysed features, the regression model was not used in further analyses. When testing for significant differences between two ordinal samples, Spearman’s ranked correlation was calculated. When one of the dimensions was categorical and the other ordinal, the data were grouped by the categorical values and the Kruskal-Wallis H-test was carried out to evaluate if at least one group’s median was different from the others. Finally, if the analysed data consisted of two categorical samples, Fisher’s test for contingency table analysis was used, or the Chi-squared approximation, where appropriate. All analysis was carried out using Haskell programming language. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

Results

Among the participants of the study (554) there were 182 men (32.9%) and 372 women (67.1%).

In men, the results were as follows. Retirees were significantly shorter compared with employed men (p=0.005). Students weighed significantly less compared with both retirees and employed men (p<0.001). The BMI of students was significantly lower compared with that of both retirees and employed men (p<0.001). Retirees scored significantly more depression points compared with both students and employed men (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of male participants, N=182

*p<0.05.

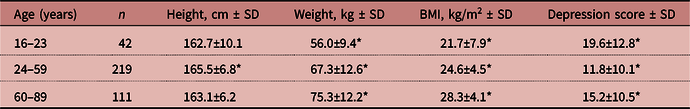

Among women, retirees were significantly shorter compared with employed women (p=0.001). For women’s weight, BMI and depression score, statistically significant differences (p<0.001) were obtained between all age groups. While weight and BMI consistently increased with age, female students scored more depression points compared with retirees who, in turn, outscored employed women (Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of female participants, N=372

*p<0.05.

In all age groups, men were significantly taller and heavier than women. The significant differences in BMI between the two sexes were absent in students; at the age of 24–59 years, men were found to have higher BMI (p<0.001) and at the age of 60–89 years they had a lower mean BMI (p=0.005) than women of the same age. The significant differences in depression score between the two sexes were absent in employed participants. At the age of 16–23 years, women were found to have higher depression scores (p=0.002), and at the age of 60–89 years lower depression scores (p=0.01), than men of the same age (Tables 1 and 2). Young women (16–23 years) and older men (60–89 years) presented the highest and very similar depression scores with no statistically significant difference between them (19.6±12.8 and 21.6±14.8 respectively, p=0.51).

Some correlations were obtained as well. There was a significant negative correlation between height and depression score (rho=−0.1322, p=0.002). However, for men and women tested separately, significant correlations between height and depression score were not found (rho=−0.1282, p=0.0846, and rho=−0.0771, p=0.1385, respectively). Furthermore, no significant correlations were obtained between height and depression score in either employed or retired participants; only in students was a significant negative correlation found (rho=−0.3307, p=0.002). Another significant negative correlation was obtained between height and depression score in the participants with normal BMI (rho=−0.2228, p<0.001); no significant correlations between height and depression score were found in underweight, overweight or obese individuals.

No significant correlation was obtained between BMI and depression score (rho=0.0542, p=0.2031). However, after the analysis of correlations between age and depression score in different BMI groups (underweight/normal/overweight/obese), a significant positive association was obtained in the group of overweight participants (rho=0.2427, p<0.001), and a nearly significant positive one in the group of obese individuals (rho=0.2068, p=0.06).

Discussion

The modern scientific literature agrees that the risk for depressive disorders is undoubtedly positively linked with BMI (Bjerkeset et al., Reference Bjerkeset, Romundstad, Evans and Gunnell2007; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Salas, Tabet, Kasper, Elder, Staley and Brownson2017; Rivera et al., Reference Rivera, Rovira, Cervilla, Ching-López, Martín-Laguna and Bandrés-Ciga2017b; Assari et al., Reference Assari, Caldwell and Zimmerman2018; Tyrrell et al., Reference Tyrrell, Mulugeta, Wood, Zhou, Beaumont and Tuke2019), with only a few authors reporting associations between short stature and depression (Speed et al., Reference Speed, Jefsen, Boerglum, Speed and Oestergaard2019). The results of the present study indicate a significant correlation between depression and short stature but not BMI. In addition, the study found that in overweight and obese men, the severity of depression increased with age. Similar results have been reported in women (Carter & Assari, Reference Carter and Assari2017). Contrary to the results of this study, underweight male adults (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wang and Basu2018) and obese female adolescents (Quek et al., Reference Quek, Tam, Zhang and Ho2017) had the highest depression levels.

A possible limitation of the current study is the use of self-reported height and weight. However, Spencer et al. (Reference Spencer, Appleby, Davey and Key2002) showed that such data are valid for the identification of relationships in epidemiological studies. Furthermore, biases in self-reports of body weight and height are similar in both depressed and non-depressed people (Jeffery et al., Reference Jeffery, Finch, Linde, Simon, Ludman and Operskalski2008).

In conclusion, this study found a significant correlation, in this sample of adults in Russia, between depression and short stature in young men, depression and short stature in participants of normal BMI, and depression and age in overweight participants. Young women (16–23 years) and older men (60–89 years) presented the highest and very similar depression scores with no statistically significant difference between them. Special attention should be paid to these groups in Russia due to their higher risks of depressive disorders.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.