Introduction

Adolescent mental health problems remain an important global public health issue. The World Health Organization (2020) estimated that 16% of the global burden of disease and injury among young people aged 10-19 years was attributed to mental health problems. Findings from the World Mental Health Surveys among adolescents in 17 countries demonstrated the global prevalence of mental health conditions to range from 10-20% (Kessler, Angermeyer, et al., Reference Kessler, Angermeyer, Anthony, De Graaf, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, De Girolamo, Gluzman, Gureje, Haro, Kawakami, Karam, Levinson, Medina Mora, Oakley Browne, Posada-Villa, Stein, Adley Tsang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee, Heeringa, Pennell, Berglund, Gruber, Petukhova, Chatterji and Ustün2007). In addition, a meta-analysis of 41 studies from 27 countries showed that the worldwide pooled prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents was 13.4%, and the prevalence of any anxiety and depressive disorders were 6.5% and 2.6%, respectively (Polanczyk et al., Reference Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye and Rohde2015). Mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are documented as leading contributors to illness and disabilities among adolescents aged 15-19 years (World Health Organization, 2020).

Due to changes in physical, social, and cognitive aspects, adolescents are vulnerable to psychological distress, and therefore, early mental health and psychological well-being promotion are important to combat the development of mental health problems (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Chan and MacBeth2018). American Psychological Association (2020) defines psychological distress as “a set of painful mental and physical symptoms that are associated with normal fluctuations of mood in most people”. This term encompasses a range of symptoms or experiences of emotional suffering or deeply unpleasant feelings (e.g., depressive or anxiety symptoms) due to stressors that are hard to cope with in everyday life (Arvidsdotter et al., Reference Arvidsdotter, Marklund, Kylén, Taft and Ekman2016; McLachlan & Gale, Reference McLachlan and Gale2018). In some cases, psychological distress can be an indication of the beginning of mental illness (American Psychological Association, 2020). Psychological distress is also shown to be associated with the increased risk of non-communicable diseases (Eriksson et al., Reference Eriksson, Ekbom, Granath, Hilding, Efendic and Östenson2008; Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Fuhrer, Shipley and Marmot2002), suicidal behaviours (Putra & Artini, Reference Putra and Artini2022), and mortality (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Stout, Lynch, Mattis, Tran, Antun, Ribeiro, Stein and Kempton2019). Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 or K10) (Furukawa et al., Reference Furukawa, Kessler, Slade and Andrews2003) and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) (Goldberg & Blackwell, Reference Goldberg and Blackwell1970) that encompass symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other negative mental health states are commonly used to assess psychological distress. Previous studies using school-based data measured adolescent psychological distress using separate items, such as anxiety and loneliness, or a combination of both (Atorkey & Owiredua, Reference Atorkey and Owiredua2021; Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021). A variety in measures to assess psychological distress among adolescents was also reported (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Chan and MacBeth2018; Siziya & Mazaba, Reference Siziya and Mazaba2015; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Zhang, Miao and Pan2021).

In Indonesia, the prevalence of depressive symptoms and emotional mental problems among adolescents aged 15-24 years reported in the Riset Kesehatan Dasar (Basic Health Research) in 2018 were 6.2% and 10.0%, respectively (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2018). Based on the data of the Indonesia Global School-based Student Health Survey (IGSHS) in 2015, the prevalence of psychological distress measured as loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance among school-going adolescents (12-19 years) was 6.16% and 4.57%, respectively (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2015). Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak (Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022) using the 2015 IGSHS reported that the prevalence of psychological distress (i.e., combining measures of loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance) among Indonesian students was 7.3%. There appears to be a limited number of studies that investigated the factors associated with adolescent psychological distress within the Indonesian context (Dhamayanti et al., Reference Dhamayanti, Noviandhari, Masdiani, Pandia and Sekarwana2020; Marthoenis et al., Reference Marthoenis, Fathiariani and Sofyan2018; Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022; Mutyahara & Prasetyawati, Reference Mutyahara and Prasetyawati2018; Widyasari & Yuniardi, Reference Widyasari and Yuniardi2019). Therefore, further studies are warranted to fill this evidence gap.

Understanding factors associated with adolescent psychological distress is important since the onset of major mental health conditions usually occurs during adolescence and the detrimental consequences of untreated adolescent mental health problems might persist and extend to adulthood (Kessler, Amminger, et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Üstün2007; World Health Organization, 2020). Age (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a), gender (Siziya & Mazaba, Reference Siziya and Mazaba2015), health-related behaviours, such as substance use (cigarette smoking, alcohol use, or drug use) (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Aboagye, Arthur-Holmes, Hagan, Okyere, Budu, Dowou, Adu and Seidu2021; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020b) and sedentary behaviour (Vancampfort, Ashdown-Franks, et al., Reference Vancampfort, Ashdown-Franks, Smith, Firth, Van Damme, Christiaansen, Stubbs and Koyanagi2019; Vancampfort, Van Damme, et al., Reference Vancampfort, Van Damme, Stubbs, Smith, Firth, Hallgren, Mugisha and Koyanagi2019) were found to be associated with psychological distress among adolescents. In addition, according to a conceptual framework proposed by World Health Organization (2005), adolescents’ social environments, including parental-, school- or friend-, and community-induced factors can serve as either a risk or protective factor for their mental health. Adolescence is a sensitive period of social interaction, and the influence of social environmental factors is profound on the development of their socio-cognitive skills and mental well-being (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Tomova and Blakemore2020). Findings from previous studies demonstrated that negative social interactions such as being bullied (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017) and interpersonal violence (e.g., being physically attacked and having physical fights) (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021) were associated with increased psychological distress among adolescents. Whereas, better relationships with peers (e.g., social support), having close friends (Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020c; Siziya & Mazaba, Reference Siziya and Mazaba2015), and better parental involvement (e.g., connectedness, bonding) (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Zhang, Miao and Pan2021) were protective against psychological distress. To our knowledge, no studies within the context of Indonesia (including the study by Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak (Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022)) explored the extent to which the influence of these social environmental factors on adolescent psychological factors varies by gender. Earlier studies showed gender differences in the associations between social environmental factors and suicidal behaviours among Indonesian adolescents (Putra et al., Reference Putra, Karin and Ariastuti2019). Therefore, understanding gender differences in social environmental factors of psychological distress is important to add to the current knowledge which in turn can potentially inform targeted public health interventions.

Accordingly, this study primarily aimed to identify social environmental factors of psychological distress among Indonesian adolescents using data from the 2015 IGSHS. Given that gender might also modify the influences of different social environmental factors on psychological distress, the potential gender differences in the factors associated with psychological distress were examined in this study.

Methods

Study design and data

This was a cross-sectional study using the most recent data from the Indonesia Global School-based Student Health Survey (IGSHS) in 2015. This national survey was conducted by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention aimed to document health risk behaviour among Indonesian school-going adolescents. The sampling for 2015 IGSHS involved two-stage clustered probability sampling. In the first step, a representative sample of schools (75 junior and senior high schools) was selected using the probability proportional to size (PPS) method in provinces mostly covering Java and Sumatra islands and also other provinces in other islands. This step was then followed by the selection of classrooms using systematic sampling in selected schools (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2015). Data were collected using an anonymous self-administered questionnaire. Further information about the 2015 IGSHS’s methodology, findings, and dataset can be found elsewhere (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). In general, GSHS’s methodology has been standardised across countries (Fleming & Jacobsen, Reference Fleming and Jacobsen2009), and GSHS questionnaire has been tested for validity and reliability (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Roberts, Perloe, Bainivualiku, Richards, Gilman and Striegel-Moore2010). In this present study, we included all available records of adolescents who participated in the 2015 IGSHS, and only excluded those with missing information on components of psychological distress (i.e., loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance). Out of 11,142 records of school-going adolescents available in the 2015 IGSHS, 136 records were omitted due to missing values, leaving a total sample of 11,006 adolescents. We decided to not omit missing values on independent variables to avoid further sample loss and to maintain the prevalence of both loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance in the dataset similar to what was reported in the 2015 GSHS report. This is important to correctly estimate the prevalence of psychological distress developed using both the aforementioned psychological measures.

Variables

The dependent variable was psychological distress and was defined following some previous studies that used the GSHS data (Atorkey & Owiredua, Reference Atorkey and Owiredua2021; Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021). Psychological distress was determined using two variables from the GSHS, namely loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance. Responses for both items (feeling lonely and anxious in the last 12 months) were re-coded as “never = 0, rarely/sometimes = 1, most of the time = 2, and always = 3”, and then summed up. Those with a total score of three or more were grouped as experiencing psychological distress (Marthoenis & Schouler-Ocak, Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a). Findings from exploratory factor analysis indicated that both loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance had high factor loading (>0.8). However, these components of the psychological distress measure had low reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.57). Due to low reliability, we also analysed loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance as separate dependent variables in addition to psychological distress. This also expanded the previous work by Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak (Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022) that only explored psychological distress.

Based on the conceptual framework proposed by the World Health Organization (2005) on the importance of social environments among adolescents, we selected the main independent variables depicting social interactions with peers and parents. The selection of social environmental variables was also informed by past works (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021). Social environmental characteristics comprised parental supervision, connectedness, bonding, peer support, having close friends, the experience of bullying, physical fight, and physical attack. Our analysis also included covariates such as demographic characteristics and health-related behaviours. Demographic characteristics included gender, age, and experience of hunger as a proxy for socioeconomic status as was done in previous studies (Dendup et al., Reference Dendup, Putra, Dorji, Tobgay, Dorji, Phuntsho and Tshering2020; Dendup et al., Reference Dendup, Putra, Tobgay, Dorji, Phuntsho, Wangdi, Yangchen and Wangdi2021; Putra & Dendup, Reference Putra and Dendup2022). Substance use (smoking, alcohol, drugs) and sedentary behaviour were included under health-related behaviours. The operational definition of the variables used in this study is presented in Table 1. Response options of the variables were dichotomised following previous studies (Atorkey & Owiredua, Reference Atorkey and Owiredua2021; Dendup et al., Reference Dendup, Putra, Dorji, Tobgay, Dorji, Phuntsho and Tshering2020; Dendup et al., Reference Dendup, Putra, Tobgay, Dorji, Phuntsho, Wangdi, Yangchen and Wangdi2021; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021; Putra & Dendup, Reference Putra and Dendup2022).

Table 1. Description of variables used in the study

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the samples and cross-tabulations were applied to present the prevalence of loneliness, anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, and combined measures of psychological distress by independent variables. Binary logistic regression was employed for bivariate and multivariate analyses to examine unadjusted and adjusted associations between social environmental factors and all psychological distress variables controlling for demographic characteristics and health-related behaviours. Separate multivariate models using the enter method by taking into account all independent variables in the same model were developed for each dependent variable (loneliness, anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, and psychological distress). Analyses were conducted in STATA using the survey command “svy” to adjust for sampling weight and clustering effect of the sampling method employed in the 2015 IGSHS and to provide robust estimates of the associations. Weighted percentages were reported for descriptive analyses. Results were presented as odds ratio (OR) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values.

Results

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the samples and the prevalence of psychological distress by demographic characteristics, social environmental factors, and health-related behaviours. The majority of school-going adolescents were aged ≤ 15 years (82.32%) and an almost equal number of girls and boys were recruited (51.28% vs. 48.47%). Only 4.07% of the adolescents reported that most of the time or always, they went hungry because of not having enough food at home. The majority did not receive adequate parental supervision (63.12%), connectedness (64.53%), and bonding (59.30%). Similarly, more than half of the adolescents (60.01%) reported not receiving peer support. Nearly 3% of them reported not having close friends at all and less than 20% were bullied at least one day in the last month. While 22.93% of the adolescents have involved in a physical fight, and 32.32% were physically attacked. In addition, the proportions of adolescents who had ever smoked, drank alcohol (in the last 30 days), and used drugs (in a lifetime) were 11.18%, 4.12%, and 2.41%, respectively. More than one-fourth of the adolescents spent at least three hours doing sitting activities per day (26.78%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the samples and the prevalence of psychological distress by independent variables

*weighted percentage

The prevalence of loneliness, anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, and psychological distress among Indonesian school-going adolescents was 6.12%, 4.52%, and 8.04%, respectively. While the prevalence of self-reported loneliness and psychological distress was higher among girls, the prevalence of anxiety-induced sleep disturbance was slightly higher among boys. The prevalence of loneliness, anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, and psychological distress was consistently higher among adolescents who were older (> 15 years), experienced hunger, without adequate parental supervision, connectedness, and bonding, did not have close friends, were bullied, involved in a physical fight, and were physically attacked. The prevalence of all measures of distress was also higher among those who used substances (cigarette smoking, alcohol, drugs) and were sedentary.

Table 3 presents bivariate analyses of social environmental factors associated with all measures of psychological distress. While receiving parental supervision, connectedness, and peer support was associated with a lower likelihood of loneliness and psychological distress, parental bonding appeared to be a protective factor for anxiety-induced sleep disturbance. Other factors such as having no close friends, being bullied, being involved in a physical fight, and being physically attacked, were consistently associated with an increased likelihood of all measures of psychological distress. In addition, using any substances and sedentary behaviour was associated with increased psychological distress. For demographic characteristics, being older was associated with a higher likelihood of anxiety and psychological distress. Meanwhile, gender was only associated with loneliness, of which boys were less likely to feel lonely than girls. Being hungry was associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing all psychological distress variables.

Table 3. Bivariate analyses of factors associated with psychological distress

ref = reference group; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

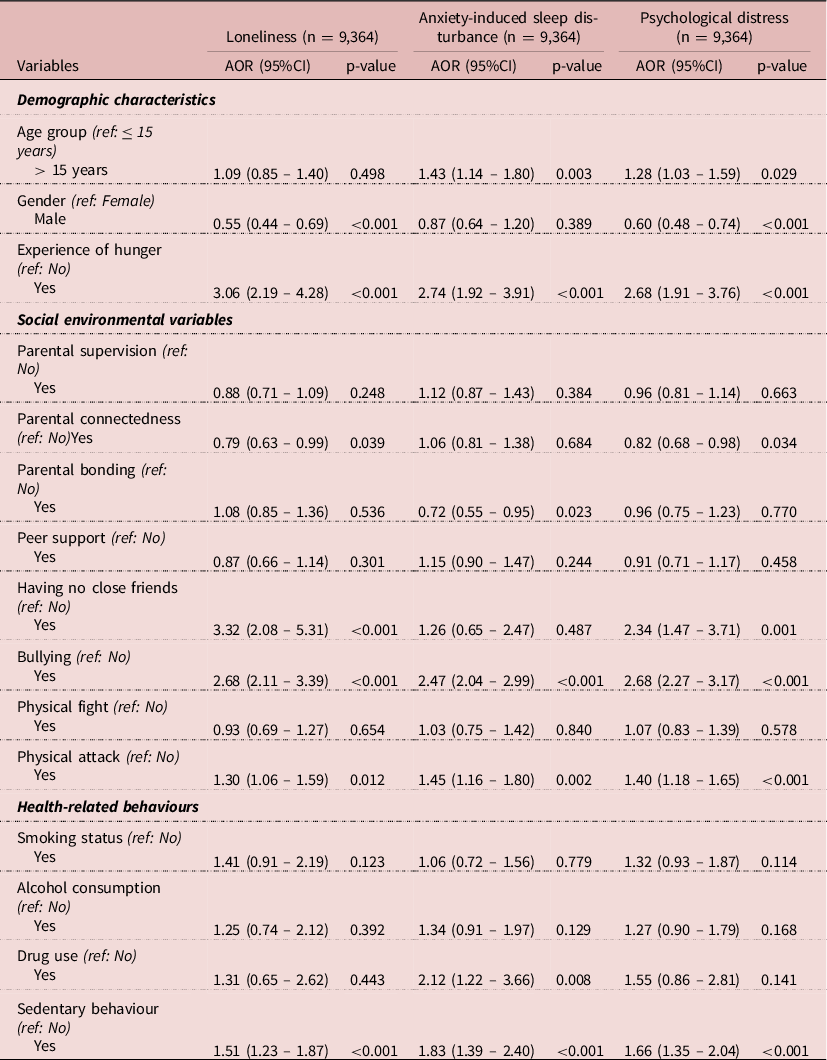

Adjusted associations between independent variables and all measures of psychological distress are presented in Table 4. Multicollinearity tests using correlation analyses showed that the independent variables were not highly correlated (r < 0.5). Parental connectedness emerged to be a protective factor for loneliness and psychological stress, and parental bonding was protective against anxiety. Moreover, having no close friends was associated with an increased likelihood of feeling lonely and experiencing psychological distress. Being bullied and physically attacked was associated with experiencing all measures of psychological distress. Age was associated with anxiety and psychological distress, and gender was associated with loneliness and psychological distress. Those who reported being hungry and sedentary were more likely to experience all measures of psychological distress. Adolescents who used drugs were also about 2 times more likely to feel anxious than those who did not.

Table 4. Multivariate analyses of factors associated with psychological distress

ref = reference group; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

Figure 1 shows the differences in correlates of all measures of psychological distress by gender. Experiencing hunger and being bullied was associated with all psychological distress variables for both girls and boys. For both genders, having no close friends was associated with loneliness and psychological distress. Those girls and boys who were sedentary were more likely to experience anxiety-induced sleep disturbance and psychological distress. A statistically significant association between sedentary and loneliness was observed among girls only. In addition, social environmental factors such as parental connectedness emerged to be a protective factor for loneliness and overall psychological distress among female samples only. Similarly, receiving peer support was associated with a decreased likelihood of loneliness among females. Furthermore, statistically significant associations between physical attack and all psychological distress variables were found among girls.

Figure 1. Gender-disaggregated multivariate analyses of factors associated with psychological distress.

Discussion

Overall, findings from this study suggest that the prevalence of psychological distress among Indonesian school-going adolescents was 8.04%, which is much lower than the prevalence reported in other studies in developing nations that used the same definition of psychological distress, such as Morocco (23.3%) (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a) and Liberia (24.5%) (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2021). The prevalence of psychological distress in our study was slightly higher compared to the study by Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak (Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022) conducted using the same data (8.0% vs. 7.3%). The study by Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak (Reference Marthoenis and Schouler-Ocak2022) removed all observations with missing values on independent variables, resulting in a reduction in sample size (n = 8,698 vs. 11,006 in our study). In addition, we took into account sample weights to correctly estimate the prevalence, following the 2015 IGSHS report (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2015).

The heterogeneity of socio-cultural contexts of study settings might explain the diverse findings on the prevalence of adolescent psychological distress in this study compared to studies from other countries. For example, components of psychological distress derived from self-reports among adolescents might be influenced by social desirability bias due to cultural and religious values of mental health. The stigma related to mental health issues in Indonesian society might lead to underreporting of mental health problems and put the sufferers at a disadvantage (Hartini et al., Reference Hartini, Fardana, Ariana and Wardana2018; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Karin and Ariastuti2019). Moreover, the prevalence of contributing factors of psychological distress, such as the experience of hunger (used as a proxy for socioeconomic measures) was higher in Morocco (9.20%) (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a) and Liberia (16.60%) (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2021) compared to 4.07% in our study that might also contribute to differences in the prevalence of psychological factors. However, further investigation is needed to explore differences in the prevalence of psychological distress across countries, such as possible clinical explanations. Although the prevalence is seemingly low among Indonesian adolescents, psychological distress during adolescence might have long-term impacts and manifest in adulthood (Goosby et al., Reference Goosby, Bellatorre, Walsemann and Cheadle2013). Therefore, understanding psychological distress and the associated factors among younger population is important in designing public health policies and programs in a targeted manner.

This present study found that some factors were consistently associated with all measures of psychological distress, such as the experience of hunger, bullying victimisation, being physically attacked, and sedentary behaviour. Other factors that included age, gender, parental connectedness and bonding, having no close friends, and drug use were associated with one or two measures of psychological distress. In addition, the influences of some social environmental variables (i.e., physical attack, parental connectedness, peer support) were more pronounced among female samples only.

The prevalence of loneliness and psychological distress was found to be lower among males, indicating that males were less likely to experience loneliness and psychological distress than females. Similarly, findings from previous studies from different settings suggest that being female was associated with increased odds of having psychological distress (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021). In general, internalising problems (e.g., psychological distress, depression) were more likely to be reported by females than males (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Chan and MacBeth2018; Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Achenbach, Ivanova, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg, Bird, Broberg, Dobrean, Döpfner, Erol, Forns, Hannesdottir, Kanbayashi, Lambert, Leung, Minaei, Mulatu, Novik, Oh, Roussos, Sawyer, Simsek, Steinhausen, Weintraub, Metzke, Wolanczyk, Zilber, Zukauskiene and Verhulst2007). Besides, females are vulnerable to stress due to biological predispositions, such as experiencing hormonal fluctuations (e.g., menstruation), as well as, social factors (e.g., social expectations from gender roles) that can provoke psychological distress (Hantsoo & Epperson, Reference Hantsoo and Epperson2017; Mayor, Reference Mayor2015; Parker & Brotchie, Reference Parker and Brotchie2010). Furthermore, older adolescents were more likely to experience anxiety-induced sleep disturbance and psychological distress. This might be due to socio-cognitive development that allows for considering uncertain future and social expectations, and changes in physical and psychosocial aspects (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Davenport and Mazanov2007; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a).

Previous work showed that hunger and food insecurity was associated with psychological distress (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Becerra and Becerra2018; Rani et al., Reference Rani, Singh, Acharya, Paudel, Lee and Singh2018; Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Park, Shearston, Lee and Weitzman2017). Low intake of calorie due to inadequate food consumption might be associated with emotional reactivity, which in turn, lead to mental health problems (Peltzer & Pengpid, Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2017a). Concerning the experience of hunger as a proxy of low socioeconomic status, children from low socioeconomic families are more likely to have fewer social skills that potentially inhibit the development of social interactions and contribute to loneliness, anxiety, and psychological distress (Peltzer & Pengpid, Reference Peltzer and Pengpid2017b). Another possible explanation that people from the low-income group are vulnerable to psychological distress could be due to unfavourable living situations such as less-safe neighbourhoods and low local amenities that can deter positive social contact with and receiving support from others (Kearns et al., Reference Kearns, Whitley, Tannahill and Ellaway2015).

Adverse impacts of negative social environments, such as bullying victimisation on psychological distress have been documented (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2019; Putra & Dendup, Reference Putra and Dendup2022). Negative peer interactions, such as being bullied or interpersonal violence and rejection by peers can be stressful life events and sources of psychosocial stressors among adolescents that can contribute to the development of psychological distress (Ferguson & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Ferguson and Zimmer-Gembeck2014; Platt et al., Reference Platt, Kadosh and Lau2013). Those with these psychosocial stressors also tend to have low self-esteem and negatively interpret their social environment and are more anxious about peer interactions (Swearer & Hymel, Reference Swearer and Hymel2015; Tsaousis, Reference Tsaousis2016). Other unpleasant peer-related situations such as having no close friends and being physically attacked were also found as determinants of psychological distress and suicidal behaviours (Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a, 2021; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Karin and Ariastuti2019; Sauter et al., Reference Sauter, Kim and Jacobsen2020). Stronger associations between the experience of being physically attacked and psychological distress among girls in this present study might be due to gender-typical behaviours. Girls were less likely to cope with physical aggression by themselves, whereas boys tend to fight back the peer aggressor as a coping strategy (Cava et al., Reference Cava, Ayllón and Tomás2021).

Parental connectedness was protective against loneliness and psychological distress, and similarly, parental bonding was protective against anxiety-induced sleep disturbance. Results from gender-disaggregated analyses suggest stronger influences of parental connectedness on loneliness and psychological distress, and of peer support on loneliness, among girls only. In many societies, females tend to have strong social relationships due to greater intimacy than males. They also have more self-disclosure and are active in seeking social support. By contrast, males tend to be less involved in intimate discussions with friends and reluctant in seeking social support when facing problems (Jobe-Shields et al., Reference Jobe-Shields, Cohen and Parra2011; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Collings, Jenkin and River2018). The influence of gender norms in most Asian countries, including Indonesia might also play important roles. Males are expected to be strong emotionally, and hence, they might not easily disclose their problems to others (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Amit, Che Din and Ong2017). This is also supported by findings in a previous study suggesting that men were less able to open up to friends and family than females (Henning-Smith et al., Reference Henning-Smith, Ecklund, Moscovice and Kozhimannil2018; McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Collings, Jenkin and River2018). This socio-cultural context might help explain the non-statistically significant influences of parental connectedness and peer support on psychological distress among boys.

From health-related behaviours, sedentary behaviour appeared as a consistent predictor for all dependent variables, irrespective of gender. Findings from a systematic review suggest consistent evidence of the association between sedentary behaviour, particularly leisure screen time with a range of mental health outcomes (Hoare et al., Reference Hoare, Milton, Foster and Allender2016). Previous analyses using GSHS data from multiple countries also found that sedentariness was associated with depressive symptoms, loneliness, and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance (Vancampfort, Ashdown-Franks, et al., Reference Vancampfort, Ashdown-Franks, Smith, Firth, Van Damme, Christiaansen, Stubbs and Koyanagi2019; Vancampfort et al., Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Firth, Van Damme and Koyanagi2018; Vancampfort, Van Damme, et al., Reference Vancampfort, Van Damme, Stubbs, Smith, Firth, Hallgren, Mugisha and Koyanagi2019). Adolescents who are sedentary cut back on time spent on physical activity that potentially reduces the positive effects of being physically active on social, general, pathophysiological, and mental health aspects (Hoare et al., Reference Hoare, Milton, Foster and Allender2016; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Li, Gan, Wang, Jiang, Cao and Lu2020; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020a). The association between being sedentary and psychological distress may also be explained by the inflammatory process (Vancampfort, Van Damme, et al., Reference Vancampfort, Van Damme, Stubbs, Smith, Firth, Hallgren, Mugisha and Koyanagi2019). The result also showed that drug use was associated with anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, which is congruent with findings from past studies (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Aboagye, Arthur-Holmes, Hagan, Okyere, Budu, Dowou, Adu and Seidu2021; Pengpid & Peltzer, Reference Pengpid and Peltzer2020b). The use of drugs as a coping attempt for stress among adolescents might be dysfunctional and maladaptive that can trigger anxiety disorders (Ahinkorah et al., Reference Ahinkorah, Aboagye, Arthur-Holmes, Hagan, Okyere, Budu, Dowou, Adu and Seidu2021; Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky and Schmidt2007). Other substance-use variables (i.e., cigarette smoking and alcohol use) did not appear to be strong predictors of psychological distress when the influences of other variables were taken into account.

Strengths and limitations

The use of national survey data from 2015 IGSHS makes the findings applicable in Indonesia. Given the paucity of published studies on adolescents’ psychological distress in Indonesia, the findings from this study can potentially contribute to the knowledge base and help inform targeted interventions to reduce mental health problems. In addition, findings from gender-disaggregated analyses on factors associated with psychological distress serve as a new addition to the literature. The limitations include the cross-sectional design that cannot deduce the temporal relationship. The information on self-reported loneliness and anxiety-induced sleep disturbance might be underreported due to the influence of social desirability. The use of the anonymous self-reported questionnaire nonetheless might help minimise this bias to some extent. Moreover, self-reported measures might be subjected to recall bias. Furthermore, this present study is based on data that were collected in 2015. There have been changes since then. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic might have led to an increase in mental health problems including psychological distress and interrupted social connection among adolescents. Future studies are needed to better understand this problem in the current and future times.

Conclusions

Based on the data of the 2015 IGSHS, around 8% of Indonesian school-going adolescents experienced psychological distress in the last 12 months. Negative social environments such as bullying victimisation and being physically attacked in addition to the experience of hunger and sedentariness were associated with all measures of psychological distress (loneliness, anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, and combined psychological distress). Older students, females, those who did not receive adequate parental connectedness and bonding, did not have any close friends, and used drugs had an increased likelihood of experiencing one or two measures of psychological distress. The findings also suggest potential gender differences in the social environmental factors associated with psychological distress. Policy interventions in public health programs intended to reduce bullying and interpersonal violence, encourage and foster healthy relationships with peers and parents, promote healthy lifestyles by increasing physical activity, and prevent substance use might help reduce the risk of psychological distress and associated negative health and social impacts. Interventions focused on older students, females, and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds might result in larger gains.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Health of Indonesia, the World Health Organization, and the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention for conducting the 2015 IGSHS and making the report and dataset publicly available online. We also thank all students who participated in the 2015 GSHS.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organisation.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The 2015 IGSHS has been approved by the Ethics Commission of the Ministry of Health of Indonesia.