Introduction

The termination of an unintended pregnancy – induced abortion – is a common gynaecological procedure across the world (Appiah-Agyekum, Reference Appiah-Agyekum2014; Ganatra et al., Reference Ganatra, Gerdts, Rossier, Johnson, Tuncalp and Assifi2017). Developing countries such as those in Africa, Asia and Latin America account for the majority of total global annual abortions (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Remez, Sedgh, Kwok and Onda2017). The practice of abortion in and of itself is not necessarily wrong despite negative cultural, religious and social assertions; it forms part of women’s reproductive rights in deciding what happens to their bodies. However, the conditions in which these abortions occur raise concerns. Out of the global 55.7 million abortions that occurred every year from 2010 to 2014, 30.6 million were classified as safe, while 25.1 million were classified as unsafe (Ganatra et al., Reference Ganatra, Gerdts, Rossier, Johnson, Tuncalp and Assifi2017). Almost all the global unsafe abortions (about 97%) taking place between 2010 and 2014 were in developing countries (Grimes et al., Reference Grimes, Benson, Singh, Romero, Ganatra, Okonofua and Shah2006; Ganatra et al., Reference Ganatra, Gerdts, Rossier, Johnson, Tuncalp and Assifi2017), with Africa accounting for 29% (WHO, 2018).

Many abortions are performed by untrained persons or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, particularly in African countries (WHO, 2018). This presents many public health challenges, the most common being abortion-related morbidity and mortality (Grimes et al., Reference Grimes, Benson, Singh, Romero, Ganatra, Okonofua and Shah2006). Globally, 68,000 women die from unsafe abortions every year, which makes it a leading cause of mortality (Haddad & Nour, Reference Haddad and Nour2009). In sub-Saharan Africa, it is estimated that 520 women die for every 100,000 unsafe abortions performed (WHO, 2018). Thus, women in Africa are disproportionately affected by unsafe abortion-related deaths.

In the Ghanaian context, the relationship between abortion and maternal deaths has been well-documented. Abortion complications are among the leading contributors to maternal deaths among Ghanaian women (Sedgh, Reference Sedgh2010; Sundaram et al., Reference Sundaram, Juarez, Bankole and Singh2012). According to the 2017 Ghana Maternal Health Survey, 10% of all pregnancies in 2017 ended in an induced abortion (GSS et al., 2018). Furthermore, unsafe induced abortion is a significant contributor to maternal morbidity and death amongst Ghanaian women aged 15–49 years, accounting for 11% of all maternal deaths in 2007 (GSS et al., 2009). The rates of abortion and abortion-related deaths, albeit under-reported, are troubling considering that Ghana has relatively liberal abortion laws (Aniteye & Mayhew, Reference Aniteye and Mayhew2013; Rominski & Lori, Reference Rominski and Lori2014). These allow abortion by qualified medical personnel in the case of rape, incest, fetal abnormality or if a pregnancy is a danger to a woman either physically or mentally. Post-abortion care services are provided by the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Services, but many women still seek illegal abortions due to the stigmatization of abortion and poor knowledge of abortion legislation or policy (Polis et al., Reference Polis, Castillo, Otupiri, Keogh, Hussain and Nakua2020). This situation poses a conundrum for policymakers, who have introduced diverse interventions in an attempt to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality associated with abortion, as well as improve access to reproductive health care for all women.

The situation therefore calls for more information on whether certain groups of women are more likely than others to have an induced abortion. Since previous studies in Ghana have identified several factors that are associated with unsafe induced abortion (Atakro et al., 2018; Boah et al., Reference Boah, Bordotsiah and Kuurdong2019), knowing the profile of women who are likely to have induced abortions will help target public health interventions aimed at improving abortion practices and pinpoint interventions that will enable women to secure a safe abortion.

Many previous studies have explored the predictors of induced abortion in Ghana. However, virtually all these used data that were not nationally representative, making the findings difficult to generalize to all women in Ghana (Geelhoed et al., Reference Geelhoed, Nayembil, Asare, Schagen van Leeuwen and van Roosmalen2002; Mote & Hindin, Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014). Moreover, empirical evidence on the association between women’s characteristics and induced abortion is scarce in Ghana. Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018) explored the factors associated with abortion among women using nationally representative data from the 2014 and 2011 Ghana and Mozambique Demographic and Health Surveys. They defined abortion as ‘ever had a terminated pregnancy’, and included both induced and spontaneous abortions, thus failing to differentiate conceptually between the two types. The present study addressed this issue by assessing the factors associated with induced abortion in Ghana using data from the 2017 Ghana Maternal and Health Survey.

Methods

The data for this study came from the individual file (women data) of the 2017 Ghana Maternal Health Survey (GMHS). This contains information on 25,062 women of reproductive age (15–49 years). The GMHS is a nationally survey that collects data for the monitoring of maternal health in Ghana. The 2017 GMHS was implemented by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and the Ghana Health Service (GHS) with technical support from ICF through the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme from 15th of June to 12th of October 2017. The 2017 GMHS women’s questionnaire had a pregnancy history segment that included questions relating to all the pregnancy outcomes a woman had ever had.

The study sample included the 18,116 survey women who had experienced a pregnancy in the 5 years preceding the survey, as these had the greatest chance of having had an abortion. The outcome variable was ‘induced abortion’. Induced abortion is the intentional termination of a pregnancy so that it does not result in the birth of a child. This was measured in the GMHS by the item ‘had an abortion in the 5 years preceding the survey’. Several demographic, socioeconomic and behavioural factors of interest were tested as explanatory variables influencing the termination of pregnancy, based on their theoretical importance from empirical literature (Mote et al., Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014; Rominski & Lori, Reference Rominski and Lori2014; Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018). Thus, the analyses controlled for women’s age, parity, education, marital status, religion, ethnicity, region, place of residence, current contraceptive use, knowledge about abortion legal status and media exposure.

Some explanatory variables were operationalized and reconstructed to produce a meaningful sample for the analyses. Respondent’s current age was categorized into three groups: 15–24, 25–34 and 35–49. Age at sexual debut was categorized as ‘<18 years’ and ‘18 years and older’. The number of children ever born was measured as ‘none’, ‘1–2 births’ and ‘3+ births’. The two survey questions relating to educational attainment – ever attended school and highest educational level – were used to construct the education variable, categorized as ‘no education’, ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘higher’. Marital status was categorized as ‘single’, ‘married’ and ‘cohabiting’.

Religion was categorized as: Catholic, other Christian denomination (non-Catholic), Muslim and other religion. This is constructed from the survey’s original religion variable categories of Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, Pentecostal/Charismatic, other Christian, Islam, Traditional/Spiritualist, no religion and other. Ethnicity included Akan, Ga/Dangme, Ewe, Guan, Mole-Dagbani, Grusi-Gurma-Mande and other.

The region of residence included the ten regions of Ghana, while place of residence was dichotomized into rural and urban. Responses to current contraceptive use, knowledge of abortion legal status (if a woman knows that abortion is legal in certain circumstances) and media exposure were classed as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. For the latter, a woman was considered to be exposed to media if she read a newspaper, listened to the radio or watched television at least once a week, which is the reference period in the GMHS.

Analyses were done at the univariate, bivariate and multivariate levels. The univariate analysis used percentages and frequencies to describe the rate of induced abortion among respondents, as well as the characteristic distribution of the study population. A bivariate analysis, using Chi-squared tests, was used to examine the relationship between induced abortion and the selected explanatory variables. Lastly, a multivariate logistic regression technique was employed to estimate women’s likelihood of having an abortion. All data were weighted and analysed using Stata version 14. The results were interpreted using odds ratios (ORs), with level of significance set at p<0.05 and confidence intervals of 95%.

Results

Univariate analysis

Table 1 presents the distributions of the background characteristics of the study population, as well as the percentage of the reported induced abortion among women of reproductive age in Ghana. Out of the 18,116 women who reported having a pregnancy in the 5 years preceding the survey, 20.43% (3702) reported having had an abortion. Around eighteen per cent of respondents were aged 15–24 years; 43.8% had secondary-level education; 52.3% lived in rural areas; 57.0% belonged to ‘other Christian’ (non-Catholic) denominations; 35.3% were of Akan ethnicity; 58.0% were married; 56.1% had at least three children; and 12.2% lived in the Ashanti region. More than half (55.7%) began having sexual intercourse before the age of 18 years; 68.5% were not currently using contraceptives; 67.0% had been exposed to some form of mass media and only 10.3% knew the legal status of abortion in Ghana.

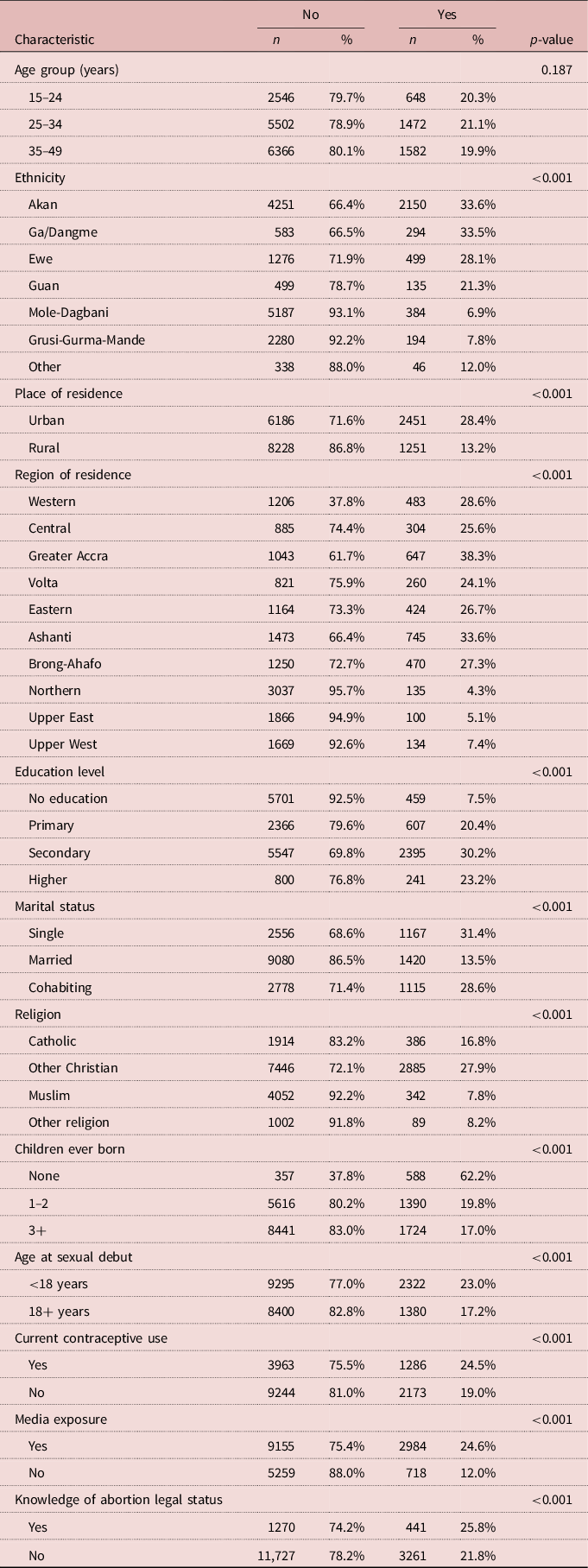

Table 1. Percentage distribution of women aged 15–49 years by background characteristics, Ghana, 2017

Bivariate analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the Chi-squared tests showing the prevalence of reported induced abortion among the women’s background characteristics. The results revealed a statistically significant relationship between induced abortion and all the selected explanatory variables, except for age. Specifically, induced abortion was more frequently reported by women who had secondary-level education (30.2%), those who lived in urban areas (28.4%) and those belonging to ‘other Christian’ denomination (27.9%).

Table 2. Prevalence and bivariate analysis of induced abortion among sample women by socio-demographic characteristics

Similarly, the incidence of induced abortion was most common among Akans (33.6%), single women (31.4%), childless women (62.2%), those in the Greater Accra region (38.3%), women who had sexual intercourse before age 18 years (23.0%), those who were currently using contraceptives (24.5%), those exposed to media (24.6%) as well as those who knew about abortion legality (25.8%).

Multivariate analysis

The logistic regression results showed that women’s age, educational attainment, place and region of residence, religion, ethnicity, marital status and the number of children ever born were significant predictors of induced abortion among women in Ghana (Table 3). Older women, particularly those aged 35–49 years (OR=2.12, CI=1.82–2.47), had a greater risk of induced abortion compared with those aged 15–24 years. Similarly, compared with those with no education, educated women were significantly more likely to terminate a pregnancy, and the finding was distinctly stronger for women who had a secondary-level education (OR=1.88, CI=1.64–2.16).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of association between induced abortion and women’s background characteristics, Ghana, 2017

* p<0.001; Ref.: reference category. Pseudo R 2 value=0.1885.

Compared with their urban counterparts, women who lived in rural areas (OR=0.61, CI=0.55–0.66) were less likely to have induced abortion. Similarly, Muslim women (OR=0.73, CI=0.60–0.88) and women of other religious beliefs (OR=0.57, CI=0.43–0.76) were less likely to have induced abortion than Catholics. Likewise, women from the Grusi-Gurma-Mande ethnic group were 0.59 times less likely to terminate a pregnancy compared with their Akan counterparts. Married women were also less likely (OR=0.70, CI=0.63–0.78) to have induced abortion than those who were single. Women who already had children were less likely to have induced abortion compared with the childless, with the relationship being stronger for those with three or more children (OR=0.13, CI=0.11–0.16). Women who resided in the Greater Accra (OR=1.36, CI=1.14–1.63) and Ashanti (OR=1.20, CI=1.03–1.40) regions were more likely to terminate a pregnancy than those in the Western region.

Sexual debut, current contraceptive use and media exposure were significantly associated with induced abortion. Specifically, women who began sexual activity at 18 years or older were less likely to have induced abortion (OR=0.49, CI=0.45–0.54) than those who began earlier. Similarly, women who were not currently using contraceptives (OR=0.74, CI=0.64–0.79), and those who were not exposed to media (OR=0.71, CI=0.64–0.79), were significantly less likely to have induced abortion.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of induced abortion in Ghana and its associated factors using data from women who reported having a pregnancy in the 5 years preceding the 2017 GMHS. Overall, about a fifth (20.4%) of the sampled women reported having had induced abortion. The bivariate results showed that education, place of residence, religion, ethnicity, marital status, region, age at sexual debut, current contraceptive use, knowledge about abortion legal status and media exposure were all significantly associated with induced abortion among women in Ghana. Moreover, induced abortion was higher among women living in urban areas and the Greater Accra region, as well as among Akan women. The findings on the effects of region and ethnicity corroborate those of Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018), who observed that young, rural, unmarried and Christian women had a higher prevalence of abortion. Perhaps the disproportionate incidences of abortion can be attributed to the disparities in the distribution of health resources within regions, among ethnic groups and between rural and urban locales. The finding that induced abortion was higher among women with secondary-level education is consistent with that of a previous study by Adjei et al. (Reference Adjei, Enuameh, Asante, Baiden, Nettey and Abubakari2015), which suggested that educated women had better access to abortion information. Also, the high prevalence of induced abortion among women who had access to media and who had knowledge of the legal status of abortion suggests that such women were more likely to seek an induced abortion than those without this knowledge.

The bivariate analysis found that single and childless women had a higher prevalence of induced abortion. Possibly, these women wanted to postpone childbearing until they were married, financially stable or ‘ready’ (Adjei et al., Reference Adjei, Enuameh, Asante, Baiden, Nettey and Abubakari2015). The prevalence of induced abortion was higher among women who started having sexual intercourse before the age of 18 years. This could be because women who engage in early sexual intercourse are more likely to engage in risky practices such as inconsistent or non-use of condoms (Kassahun et al., Reference Kassahun, Gelagay, Muche, Dessie and Kassie2019), which might lead to unwanted pregnancy and subsequently an abortion. The finding that induced abortion prevalence was low among Muslim women corroborates a previous finding by Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018). The low prevalence of induced abortion among Muslim women could be attributed to the rules and punishments guiding Islamic religion. The finding that induced abortion was high among younger women (15–24 years and 25–34 years) is consistent with that of a previous study by Mote et al. (Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010), which suggested that younger women who want to postpone childbearing are more likely to terminate an unwanted pregnancy.

The multivariate results showed that several women’s socio-demographic characteristics, age at sexual debut, current contraceptive use and media exposure were all significant predictors of induced abortion. The odds of induced abortion increased with a woman’s age. Specifically, women in the 25–49-year age group had a higher risk of induced abortion compared with women aged 15–24 years. This finding is consistent with previous studies in Ghana (Mote et al., Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010) and Brazil (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Coelho Ede, Gusmão, Silva, Marques and Almeida2016), which showed that women older than 30 years had the highest risk of induced abortion. A possible explanation could be that after 30 years of age, a pregnancy could be unplanned or medically complicated, leading women to decide to terminate the pregnancy. Also, it is possible that at this age, a woman may have already achieved her desired family size.

The study found that women’s level of education had a statistically significant relationship with induced abortion in Ghana. Women with primary, secondary and higher-level education were more likely to obtain an induced abortion than uneducated women. This confirms findings from previous studies in Ghana, where women’s education was reported to increase the risk of induced abortion (Mote et al., Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010; Sundaram et al., Reference Sundaram, Juarez, Bankole and Singh2012; Adjei et al., Reference Adjei, Enuameh, Asante, Baiden, Nettey and Abubakari2015). Variations notwithstanding, the over-representation of the educated among women who obtain induced abortions is unsurprising because educated women tend to know about abortion policy and services and have better access to reproductive health services in the event of an unwanted pregnancy.

Place of residence was significantly associated with induced abortion in that women in urban areas were more likely to terminate a pregnancy than rural residents. This could be attributed to the relatively better access to financial and other socioeconomic resources such as health care in urban areas. This finding is also in line with previous studies conducted in Ghana (Sundaram et al., Reference Sundaram, Juarez, Bankole and Singh2012), India (Pallikadavath & Stones, Reference Pallikadavath and Stones2006) and several low- and middle-income countries (Chae et al., Reference Chae, Desai, Crowell, Sedgh and Singh2017).

The present study also found significant ethnic and regional variations in induced abortion among women in Ghana. These results suggest that cultural and regional beliefs could potentially influence induced abortion amongst women in Ghana. While there have been inconsistent findings regarding the association between religion and induced abortion (Ahiadeke, Reference Ahiadeke2001; Schwandt et al., Reference Schwandt, Creanga, Danso, Adanu, Agbenyega and Hindin2011; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014), this study found that induced abortion was lower among Muslim women and those of ‘other religions’ in Ghana than those of Catholic faith. This could be attributed to the impact of beliefs and principles of the sanctity or inviolability of life central to some religions.

Consistent with previous studies from Ghana (Mote et al., Reference Mote, Otupiri and Hindin2010; Klutsey & Ankomah, Reference Klutsey and Ankomah2014), the present study found that the risk of induced abortion was lower among married than unmarried women. This is expected and hardly surprising, as women who are in marital unions are expected to have children, especially in the African context where children are seen as blessings of marriage. Similarly, the stigma associated with premarital childbearing could be a possible factor for the high risk of induced abortion among unmarried and cohabiting women.

Consistent with Boah et al. (Reference Boah, Bordotsiah and Kuurdong2019), this study found that women who started having sexual intercourse at 18 years or older had a lower risk of induced abortion compared with women who started sexual intercourse before their 18th birthday. Age at sexual debut is an important event, which has social, physical, mental and health implications (Amoateng & Baruwa, Reference Amoateng and Baruwa2018). Therefore, it is probable that women who start sexual intercourse earlier might be more susceptible to sexual coercion or rape, which can lead to unplanned pregnancies (Boah et al., Reference Boah, Bordotsiah and Kuurdong2019). A further possible explanation for the lower risk of induced abortion among women who delay sexual intercourse until after 18 years is that they are more likely to be physically and mentally ready to deal with the consequences of engaging in sexual intercourse.

The present study found that women who had had at least one child had a lower risk of induced abortion compared with women who have no children. There is a possibility that women who have no children are younger and would therefore like to postpone childbearing until marriage or when they are financially stable. Compared with those who were currently using contraceptives, the risk of induced abortion was lower among women who were not using contraceptives. Since contraceptive use is a fertility-inhibiting behaviour, women who do not use contraceptives may be actively trying to get pregnant, and so have no need to terminate a pregnancy as it is likely to be wanted. Media exposure was found to be significantly associated with induced abortion. Consistent with the study of Dickson et al. (Reference Dickson, Adde and Ahinkorah2018), women who had access to media and had knowledge about abortion law had a higher risk of induced abortion. This finding underscores the importance of media in providing information on sexual reproductive health, including abortion services and information about the legal status of abortion, in Ghana.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, because of the inadequate knowledge of the legality of induced abortion in Ghana, some respondents might not have accurately provided information related to abortion. Secondly, social desirability might have led to inaccurate or no responses. Lastly, the study analysed cross-sectional GMHS data, so the results should be interpreted as associations and not causal relationships. However, the study’s use of a nationally representative dataset meant the findings can be generalized to all women of reproductive age in Ghana, and restricting data to the 5 years preceding the survey minimized recall bias.

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide information on the socio-demographic predictors of induced abortion among women in Ghana. Family planning services and educational programmes on abortion services need to be strengthened in Ghana to reach the target groups identified.

Funding

This research was not funded by any organization or institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This research used secondary data which was obtained through the permission of DHSprogram.org.