Introduction

Until the 1970s global fertility rates displayed a sharp division between the ‘developed’ and the ‘developing’ countries: the period Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in the latter group averaged 5.42 births per woman in 1970–75 compared with an average of 2.15 births per woman in countries labelled as developed (United Nations, 2015). About a quarter of the world population lived in countries with a period TFR below 3, all belonging to the ‘developed’ group of nations. In the following four decades, two sweeping and initially unexpected shifts took place. First, most of the rich countries, especially in Europe, but also Canada, Japan and Singapore, experienced period fertility declines far below the replacement level threshold. Second, many of the less-developed countries saw unexpectedly swift fertility declines to levels around population replacement, thus blurring the previous fertility divide. Countries as diverse as the Republic of Korea (South Korea), Brazil and China saw their TFRs plummet from levels between 5 and 7 births per woman in the 1960s to fewer than 2 births per woman around 2010 (Basten et al., Reference Basten, Sobotka and Zeman2014; United Nations, 2015), thus entering the ‘post-transitional’ phase of development (Wilson, Reference Wilson2013; here the terms ‘transitional’ and ‘post-transitional’ are used in a rather narrow sense, referring to the fertility transition as a process of fertility decline from a high to around-replacement level). About half of the global population now live in countries with below-replacement TFR levels (Wilson & Pison, Reference Wilson and Pison2004; United Nations, 2015). Morgan and Rackin (Reference Morgan and Rackin2010, p. 529) suggested that ‘no twentieth century change has more profound implications or has been more dramatic than the rapid fertility declines around the world’.

Countries and regions that have recently seen their fertility fall towards, or below, 2 births per woman are not stepping into uncharted territory. Forces that have driven the shifts to low and very low fertility in Europe, Japan, Canada or the United States, documented in countless studies (e.g. reviews by Billari & Kohler, Reference Billari and Kohler2004; Rindfuss et al., Reference Rindfuss, Guzzo and Morgan2004; Morgan & Taylor, Reference Morgan and Taylor2006; Balbo et al., Reference Balbo, Billari and Mills2013; Basten et al., Reference Basten, Sobotka and Zeman2014), also appear to be important drivers of fertility trends in countries where fertility was high until recently (Fuchs & Goujon, Reference Fuchs and Goujon2014).

The experiences of the early post-transitional countries, characterized by diverse policies, labour markets and welfare regimes, offer lessons of cross-country diversity in fertility trends and population dynamics (Wilson, Reference Wilson2013). The long record of very low fertility in some of these countries also offers insights into its causes and sustainability, and the successes or failures of different policies aimed at stimulating fertility. Post-transitional fertility experiences also entail new and unexpected patterns suggesting that pre-transitional and post-transitional fertility regimes are qualitatively different. For instance, studies on low-fertility societies have identified a number of unexpected correlations emerging in the last two to three decades, including a positive association between economic development and fertility (Myrskylä et al., Reference Myrskylä, Kohler and Billari2009; Luci-Greulich & Thévenon, Reference Luci-Greulich and Thévenon2014), between gender equality and fertility (Arpino et al., Reference Arpino, Esping-Andersen and Pessin2015), between women’s labour participation and fertility (Rindfuss et al., Reference Rindfuss, Guzzo and Morgan2004) and between divorce, share of extra-marital births and fertility (Billari & Kohler, Reference Billari and Kohler2004). These correlations often show opposite signs in pre-transitional and post-transitional societies.

This study discusses the experiences of countries that have seen their fertility declining to, or below, replacement level in the 1950s to 1980s and summarizes the key findings that are relevant for the countries with a more recent experience of fertility declines. It highlights the diversity in fertility declines and the instability of post-transitional fertility, illustrated by the examples of countries and regions that have recently seen substantial increases in period fertility. Four key forces contributing to delayed, diverse and unstable fertility in post-transitional settings are discussed. These include the expansion of higher education, the increase in economic uncertainty – especially among young adults – the ‘gender revolution’ with the concomitant shift to almost universal labour market participation among women, and the changing character of the family.

The main aim of this study is to highlight the importance of delayed parenthood for understanding the shifts to low and very low fertility as well as fertility upturns and reversals. By the turn of the 21st century all countries with an extended record of low fertility had also experienced the onset of a long-lasting transition towards a later timing of childbearing (Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002). The shift towards delayed childbearing and its negative impact on conventional period fertility indicators have been widely documented for post-transitional countries (e.g. Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002; Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2004a, Reference Sobotkab; Bongaarts & Sobotka, Reference Bongaarts and Sobotka2012). However, its relevance for future fertility trends in the countries that are now entering their post-transitional phase has been little discussed (with the main exception of Bongaarts, Reference Bongaarts1999). This ‘postponement transition’ is a neglected factor in the debate on emerging sub-replacement fertility in these countries, in part because it has not started yet in some of them, and partly because the available data do not allow it to be documented in detail.

This study argues that many of the new post-transitional countries, including China, are at the onset of a long-lasting shift towards delayed childbearing. This shift will have similar consequences for their period fertility as it has had in Europe and other regions with a long history of low fertility: delayed childbearing is likely to push the period fertility rates in these countries well below the corresponding cohort indicators of family size for several decades.

Analysed regions and terminology used

This contribution uses the terms ‘post-transitional countries’ and ‘low-fertility countries’ interchangeably, referring broadly to the countries that experienced an early decline of period fertility (as measured by the TFR) to, or below, the replacement fertility level during the 1950s to 1980s. These include almost all European countries (with a few notable exceptions such as Albania and Kosovo), parts of East Asia (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the region of Hong Kong), Singapore, Canada, Cuba and the United States, as well as Australia and New Zealand and selected smaller territories in Oceania and elsewhere. The term ‘fertility transition’ is used rather than ‘demographic transition’ as the study focuses on fertility changes, without discussing them in conjunction with mortality trends or broader population dynamics. In addition, the terms ‘postponement transition’, first suggested by Kohler et al. (Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002), and ‘tempo transition’ are used interchangeably. They denote a shift in family formation from younger ages to higher reproductive ages.

When discussing the experiences of ‘emerging’ post-transitional countries the article focuses on the countries that have experienced a decline in period TFR to around-replacement level in the 1990s to 2000s, or that are approaching the completion of their fertility transition and currently have a period TFR of below 3 births per woman. This group includes countries and regions around the world, with the main exception of sub-Saharan Africa: almost all the countries of Latin America (with a few exceptions, especially Bolivia, Guatemala and Haiti), China, Mongolia, South-eastern Asia (except Laos and Timor-Leste), most regions of India, parts of Southern Asia (except Afghanistan and Pakistan), parts of Western Asia (especially Iran and Turkey) and the Caucasus region, parts of Central Asia, as well as most of Northern and Southern Africa.

Results

There is no post-transitional fertility equilibrium

As Coleman and Rowthorn (Reference Coleman and Rowthorn2011, p. 218) noted, until the 1980s the demographic transition theory took for granted that fertility in post-transitional populations would broadly stabilize around the replacement level. Even today, many demographers and policymakers continue seeing fertility around replacement as a desirable long-term goal and some governments design policies aimed at reaching this target. In reality, only a few post-transitional countries have experienced a stabilization of period fertility close to the replacement level and in most of them the TFR declined far below 2 births per woman. For instance, in the European Union the TFR now stands at 1.58 (2014), not much above its low of 1.44 reached in the late 1990s.

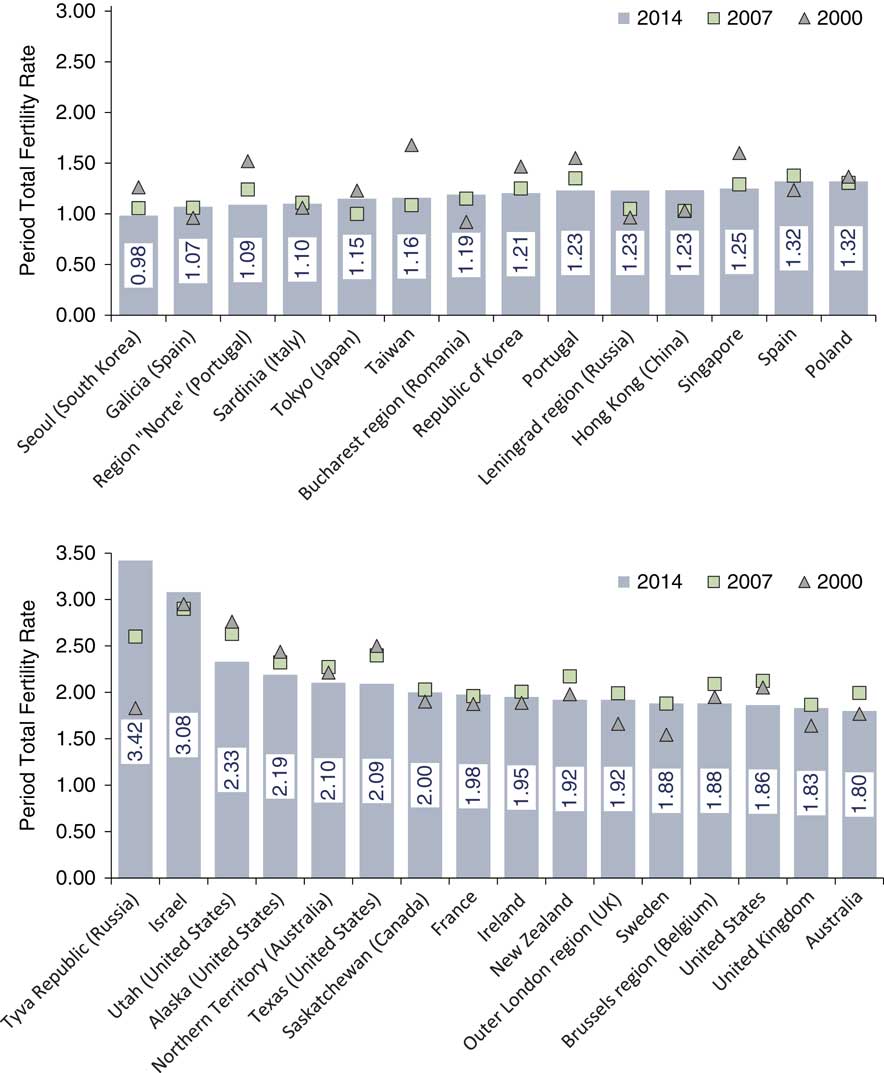

Because period fertility rates are often affected by the changes in the timing of births, a clearer picture of post-transitional fertility emerges when analysing the cohort trends. Figure 1, looking at low-fertility countries with populations at or above 20 million, shows a broad variation in their completed fertility among the women born up to the mid-1970s. Italy, Spain and Japan reached very low cohort fertility at around 1.4 births per woman, followed by Germany (1.56) and Russia (1.60). In contrast, Australia, France, United Kingdom and the United States retained around-replacement family size with completed fertility between 1.9 and 2.15 births per woman. The list of post-transitional countries with around-replacement cohort fertility (at or above 1.8) also includes the Nordic countries, Belgium, Ireland and New Zealand.

Fig. 1 Completed cohort fertility among women born in 1940–1974; post-transitional countries with population at or above 20 million. A small portion of fertility at higher ages (38+) among women born in the late 1960s and the early 1970s has been estimated. Sources: Human Fertility Database (2016), Human Fertility Collection (2015), Council of Europe (2006), national statistical offices, Sobotka et al. (Reference Sobotka, Zeman, Potančoková, Eder, Brzozowska, Beaujouan and Matysiak2015) and own computations partly based on Eurostat (2015) data.

Period fertility often falls to ‘ultra-low’ low levels

Within the broad variation of fertility in post-transitional societies it is most of all the experience of very low fertility that fuels worry and attracts most attention. Typically, low fertility has been discussed using period TFRs, which are widely available, but also easily misinterpreted, not least because they are often influenced by the changes in the timing of births and in the parity distribution of the female population (Sobotka & Lutz, Reference Sobotka and Lutz2011). Two boundaries of the period TFR have featured most prominently in demographic debates: 1.5 and 1.3. Peter McDonald suggested that rich countries are split into two groups, one where fertility is moderately below replacement, with the TFR staying above 1.5, and the other where fertility is below that level and consequently also below the ‘safety zone’, implying that the generation size will fall rapidly and massive migration would be needed to offset this decline (McDonald, Reference McDonald2006, p. 485). Rindfuss et al. (Reference Rindfuss, Choe and Brauner-Otto2016) proposed that the apparent ‘bifurcation’ of period fertility in rich countries around the 1.5 threshold signifies an emergence of two distinct fertility regimes, with a sizeable group of countries ‘stuck’ with a low period TFR.

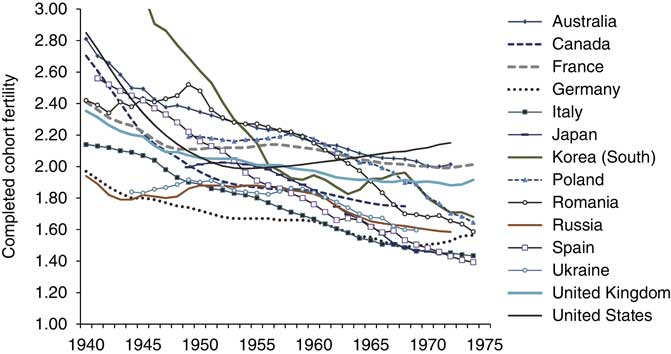

Yet another, lower, boundary of the period TFR below 1.3 first became significant in the 1990s when many Southern, Central and Eastern European countries suddenly experienced fertility decline below this ‘lowest-low’ fertility threshold (Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002). Soon thereafter, such a low fertility was experienced in many countries of Europe as well as in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and, for a short period, also in Japan. By 2002 more than half of the European population lived in countries with such a low period TFR (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Sobotka and Jasilioniene2009). Some countries and regions even recorded a TFR falling below 1, including the eastern part of Germany after German reunification (between 1991 and 1996), many provinces of Spain and Italy, especially in the 1990s, and the region of Hong Kong between 1999 and 2006. Although the TFR in many parts of Europe recovered somewhat in the 2000s, very low TFR levels are still reported in a number of countries and regions, especially after the recent economic recession. In Europe, very low TFRs in the order of 1.20–1.40 are now found especially in Southern Europe (in Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Spain), Moldova, Romania and Poland (Fig. 2). In East Asia, the TFR dipped to 1.07 in Taiwan, 1.12 in Hong Kong, and 1.19 in South Korea and Singapore in 2013, following a temporary spike in 2012 during the Year of the Dragon, which is considered auspicious for having children.

However dramatic such low fertility rates appear to be, they have often proved to be a transient phenomenon. Sobotka (Reference Sobotka2004a) analysed all European countries that had reached a TFR at or below 1.3 during the 1990s and early 2000s and concluded that such low fertility levels were driven by the tempo effect caused by the shift towards later timing of births. Without this shift, period TFR in all the analysed countries would still be low, but would stay at or above 1.4 (see also Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Sobotka and Jasilioniene2009; Bongaarts & Sobotka, Reference Bongaarts and Sobotka2012).

When considering the shifts to very low fertility it is important to highlight the wide variation in post-transitional fertility in highly developed countries. Figure 2 shows selected countries and regions with very low (TFR at or below 1.32) and relatively high (TFR at or above 1.80) period fertility in 2014. In its extremes, the TFR ranges from below 1 in Seoul, the capital of South Korea, to over 3 in Israel and a few regions in Russia and elsewhere. Very low fertility is typically concentrated in East Asia, Southern Europe and, to a smaller extent, in Central and Eastern Europe. Within countries, the lowest-fertility regions are often either booming capital cities with highly educated and highly mobile populations living in densely populated areas (Seoul, Bucharest) or in relatively peripheral regions (Sardinia, Northern Portugal).

Higher fertility at around-replacement level is most typical of North-western Europe, United States, Australia and New Zealand. Whereas most rich countries have experienced protracted sub-replacement fertility, there are also a few counter-examples of places and populations that have so far bucked the trend and retained above-replacement fertility. Israel is the most peculiar case – a rich society marked by enormous social, ethnic and religious divides and persistently high levels of period TFR that has hovered around 2.9–3.1 since the early 1980s. Such a high fertility is largely attributable to a sizeable minority of ultra-Orthodox Jews who have retained a TFR of around 7 in the last decades (e.g. Okun, Reference Okun2013). Relatively high fertility is also found in other selected regions with ethnically, religiously or culturally distinct populations, including Utah (with a high share of Mormon adherents), remote regions with high shares of aboriginal or native population with higher fertility (Alaska in the United States, Nunavut and Northwest Territories in Canada, Northern Territory in Australia, Tyva Republic in Russia), but also in some prosperous regions with ethnically and culturally diverse populations (Texas, US) and urban regions with high shares of migrants and ethnic minorities (Brussels region in Belgium).

The ‘postponement transition’ depresses period fertility rates for decades

Although their fertility rates differ considerably, post-transitional countries share the trend towards delayed family formation. It started in the early 1970s in Western Europe, United States and Japan, driven by a combination of rising women’s lifelong employment, expanding secondary and higher education, rapid spread of efficient contraception and wider access to abortion, unstable economic conditions and changing partnership and sexual behaviour (Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2010; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Rindfuss, McDonald and te Velde2011). The trend towards delayed parenthood is remarkable by its persistence, progressing in some countries such as Japan, Sweden and Switzerland without interruption for more than four decades (Table 1). In the Western world, fertility postponement brought a reversal of the trend towards earlier marriages and births during the ‘baby boom’ period in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Table 1 Key characteristics of the ‘postponement transition’ in selected low-fertility countries

MAB1 is the mean age at first birth computed from the schedule of age-specific fertility rates for first births; Adj TFR is the Total Fertility Rate adjusted for tempo effect caused by the changes in the timing of childbearing. The data used here are based either on Bongaarts and Feeney’s (Reference Bongaarts and Feeney1998) method or on its more sophisticated variant described in Bongaarts and Sobotka (Reference Bongaarts and Sobotka2012). Sources: Human Fertility Database (2016), European Demographic Data Sheet 2016 (VID, 2016) and national statistical offices. ‘Adj TFR’ taken from the European Demographic Data Sheet (VID, 2016). Data for Korea were computed by Sam Hyun Yoo (Yoo & Sobotka, Reference Yoo and Sobotka2017).

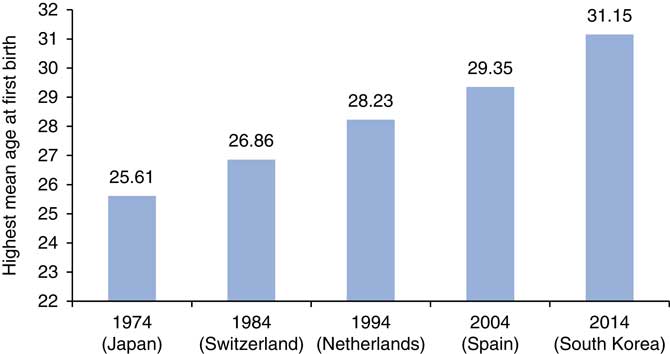

In the 1970s, women in the developed countries typically became mothers at ages 22–25. In 1975 Japanese women had the latest pattern of family formation globally, becoming mothers at age 25.6 on average. At present, the mean age at first birth in rich countries has increased to 26–30 years – a shift by 4–6 years over the last four decades (Table 1). The boundary of the highest mean age at first birth has increased without interruption after the mid-1970s, reaching 31 in South Korea in 2014 (Fig. 3). In the South Korean capital, Seoul, the mean age at first birth reached a high of 32.0 in 2015 (KOSIS, 2016). Arguably, the combination of rigid employment conditions with long and inflexible working hours, low gender equality and also the pattern of a delayed marriage in a culture where childbearing outside marriage is not accepted, contribute to the very late first birth pattern in South Korea (Lee & Choi, Reference Lee and Choi2015; Yoo, Reference Yoo2016).

Fig. 3 Highest mean age at first birth among low-fertility countries, 1974–2014. Small countries and territories with population below 1 million are excluded. Sources: Human Fertility Database (2016), Human Fertility Collection (2015), own computations using Eurostat (2015) data, and computations by Sam Hyun Yoo (Yoo & Sobotka, Reference Yoo and Sobotka2017).

This change in the timing of family formation, which was initiated in most countries when period TFR was around the replacement level of 2.1 (Table 1), has had a strong impact on period fertility. During the course of the tempo transition some of the births that would otherwise have taken place in any given year have been ‘shifted’ into the future. The size of this ‘tempo effect’ is not negligible and is proportional to the pace of increase in the mean age of childbearing (Bongaarts & Feeney, Reference Bongaarts and Feeney1998); according to recent estimates, the TFR in the European Union in 2012 of 1.57 would reach 1.72 if the age at childbearing remained stable during that year (VID, 2016). This means the tempo effect has reduced the period TFR across the EU by 0.15 on average. In individual low-fertility countries the size of the tempo effect over the last two decades has been estimated at close to nil to a sizeable −0.7 births per woman in the Czech Republic in the second half of the 1990s (Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Zeman, Potančoková, Eder, Brzozowska, Beaujouan and Matysiak2015; VID, 2016; see also estimates of tempo-adjusted TFR for selected countries in Table 1). These estimates are based on tempo-adjustment methods, which can be criticized for their underlying assumptions (e.g. Ní Bhrolcháin, Reference Ní Bhrolcháin2011), but they still give a clear indication about the role of the timing shifts in affecting the conventional period fertility measures.

Different pathways of the ‘postponement transition’

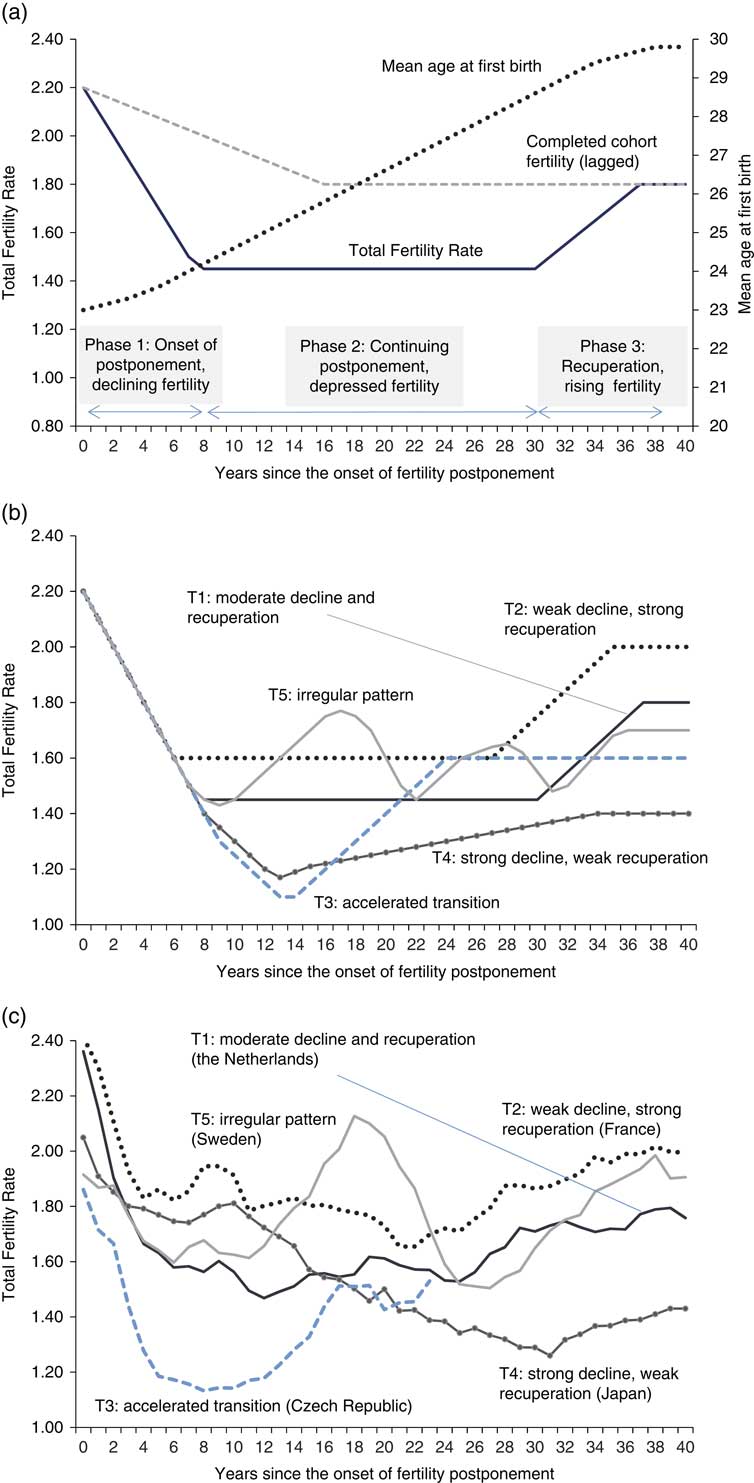

Postponement of childbearing has therefore emerged as a key factor in explaining the emergence of very low period fertility. In many countries with low fertility it has provided the decisive push that depressed their period TFR to lowest-low levels below 1.3 (Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2004a). Without shifting childbearing to higher reproductive ages, countries such as Japan, South Korea, Russia or Spain would not have witnessed such low period TFR levels over the last two decades. The ‘postponement transition’ can also be seen as a long-term shift with three phases, characterized by distinct trends in period TFR and its age-specific components (see also Chapter 3 in Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2004b). Figure 4a gives a stylized representation of this process. During the initial (first) phase women start postponing motherhood and, as a result, the TFR declines rapidly and the mean age at first birth starts rising. In most developed countries this phase overlapped with a general decline of fertility below replacement level, often resulting in impressive reductions in the TFR. In the second phase of continuing postponement, which can last for several decades, the TFR level stays low or very low, while the mean age at first birth continues rising. In reality the TFR often rises and falls during this period, but it continues being squeezed by the tempo effect. In this phase many governments express concerns about potentially negative long-term consequences of very low fertility and start paying attention to family policies, often with explicitly pronatalist aims. Finally, in the third phase of fertility ‘recuperation’, the increase in the age at first birth slows down and eventually comes to an end, the tempo effect vanishes and the TFR increases, eventually reaching similar level as the completed cohort fertility. This phase is characterized by a gradual stabilization of fertility rates at younger childbearing ages below 30 (when fertility is no longer postponed) combined with a continuing increase in fertility at later ages (when fertility that had been postponed earlier is being realized; see Frejka, Reference Frejka2012). The actual size of the TFR increase depends on the fertility trend in the course of the tempo transition: if fertility level, net of tempo distortions, continues falling during that period, the TFR may rise slowly or even remain very low (Bongaarts, Reference Bongaarts2002). Because fertility levels have declined during the postponement transition almost everywhere, the period TFR in most countries eventually settles well below the levels reached before the onset of fertility postponement.

Fig. 4 (a) Changes in period TFR, completed cohort fertility (lagged by 30 years) and mean age at first birth during the course of the ‘postponement transition’ (stylized scheme). This constitutes an elaboration of Figure 3.13 in Sobotka (Reference Sobotka2004b). (b) Five trajectories of period TFR decline and recuperation during the course of the ‘postponement transition’ (stylized scheme); (c) Five trajectories of period TFR decline and recuperation during the course of the ‘postponement transition’: empirical examples of selected countries, 1970–2015. Data sources: Human Fertility Database (2016), European Demographic Data Sheet 2016 (VID, 2016), own computations using Eurostat (2015) data and national statistical offices.

This stylized representation of the postponement transition can be elaborated to capture considerable variation in fertility postponement across low-fertility countries. Figure 4b shows five ‘model’ trajectories of postponement, distinguished by the pace and severity of TFR decline in the first phase, by the duration and stability of the second phase of depressed fertility and by the rapidity and the size of fertility increase during the third phase of fertility recovery. With respect to the depth of the TFR declines, two trajectories leading to ultra-low fertility levels can be distinguished. The first one, T3, shows an accelerated transition, where a steep TFR fall to very low levels is followed by an equally impressive fertility recovery to considerably higher levels, whereas the second trajectory, T4, shows a TFR decline to very low levels, followed by only a gradual trend towards slightly higher fertility.

These trajectories are still simplified and the actual fertility trends are much more irregular and less predictable. Nevertheless, each of these trajectories can be linked with an observed pattern of a TFR fall and increase over the last four decades (Fig. 4c). Among the countries where the TFR has recovered to moderately low levels of between 1.6 and 2.1, the Netherlands has followed a pattern of a moderate TFR decline as well as subsequent recuperation (T1), France has shown a weak TFR decline with a strong subsequent recovery (T2) and Sweden has displayed a strong recuperation combined with considerable TFR swings (T5, see also Fig. 6). In addition, two trajectories marked so far by a TFR recuperation to lower levels of 1.4–1.6 are exemplified by an accelerated postponement transition of the Czech Republic (T3) and a gradual shift to very low TFR levels and only a weak subsequent recovery in Japan (T4).

Period fertility can increase considerably

The simplified scheme of the three-phase process of fertility postponement and recuperation is challenged by the arguments suggesting that fertility is likely to stay very low and becomes difficult to reverse once it falls below a certain critical threshold (McDonald, Reference McDonald2006; Rindfuss et al., Reference Rindfuss, Choe and Brauner-Otto2016). This idea has been most extensively elaborated by Lutz et al. (Reference Lutz, Skirbekk and Testa2006) in a ‘low fertility trap’ hypothesis. It sees very low fertility as an outcome of the experiences of young people who perceive an ever greater gap between their economic aspirations and their actual income and who grow up in an environment with few children. This experience also negatively affects their family size ideals, which in turn lead to yet lower fertility.

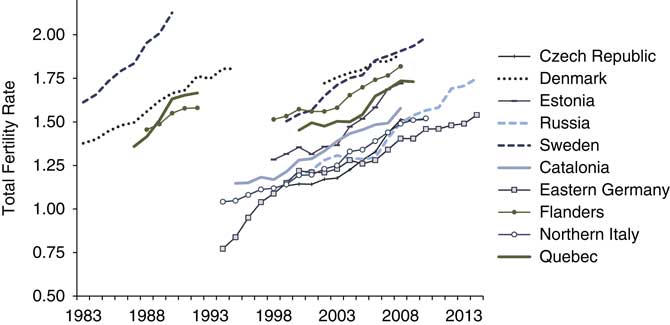

Without denying that this mechanism can be at work in some societies, especially in East Asia, the empirical evidence for a number of countries and regions in Europe, as well as Quebec in Canada, shows that TFRs can rebound robustly across diverse contexts and also from very different low thresholds. Figure 5 displays TFR increases in selected countries and regions, presenting for simplicity the TFR trajectory only during its increasing phase. The key insights provided by this figure are as follows:

-

1. The TFR rise can be almost as sudden as its decline. In some cases, including Denmark, eastern Germany, Russia and Sweden, the TFR rose by 0.5–0.7 births per woman from its lowest point in the 1980s–2000s to its subsequent peak level.

-

2. It is difficult to identify any specific threshold that would constitute a strong barrier to TFR increase. In some of the countries and regions shown in Fig. 5, the TFR rose from extreme low levels to a more ‘moderate’ low fertility at around 1.5–1.6 births per woman: such an increase took place in eastern Germany from a low of 0.77 in 1994, in northern Italy from 1.04 in 1994, in the Czech Republic from 1.13 in 1999 and in Catalonia from 1.15 in 1996. Yet in other cases the TFR ‘crossed’ the 1.5 boundary to considerably higher levels (Denmark, Estonia, Quebec, Russia) and in Sweden it shifted from 1.5 to the level just below 2.0 between 1999 and 2010.

-

3. The trajectories of TFR increase are not always straightforward and may be interrupted, for instance, during the periods of economic uncertainty. Thus, in a number of cases where the TFR increase had started already in the 1980s (Denmark, Flanders, Quebec and Sweden), two distinct periods of TFR growth can be seen, interrupted by declining fertility (not shown).

-

4. Fertility increases took place in very diverse institutional contexts, including the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, recovering from the economic shocks and social turbulences of the 1990s (e.g. Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2011; Frejka & Gietel-Basten, Reference Frejka and Gietel-Basten2016). In Estonia, Quebec and Russia pronatalist or family-oriented policies have arguably played an important role in the observed increases. However, in most countries other factors have played the key role, including favourable economic conditions, which have often been linked to the diminishing pace of fertility postponement and the resulting decline in tempo effects (e.g. Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Sobotka and Jasilioniene2009). In addition, the rise of immigrant populations with higher fertility levels has partly contributed to the observed TFR rise in some prosperous regions (Catalonia, Flanders and northern Italy).

Fig. 5 Increases in period TFR in five European countries, four subnational regions in Europe and Quebec, 1983–2015. Only periods of TFR increase shown. Sources: Human Fertility Database (2016), own computations using Eurostat (2015) data, national statistical offices for Russia and Czech Republic (most recent data), Catalonia, Flanders, eastern Germany and northern Italy; ISQ (2015) for Quebec.

Ups, downs and reversals: post-transitional fertility is often unstable

The falls and increases in period TFRs discussed above show that there is no ‘natural’ boundary around which fertility declines bottom out, but also that these declines are often reversed. Post-transitional fertility is usually unstable, at least when viewed from a period perspective. Especially under rapidly changing societal conditions (e.g. after the collapse of state socialism in Central and Eastern Europe) and during economically uncertain times couples often respond by postponing childbearing (e.g. Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Skirbekk and Philipov2011). If they manage to have the presumably postponed children later in life, period fertility might rise quickly, but cohort fertility would remain relatively stable as period ups and downs compensate one another.

A prime example of such development is Sweden, where unstable ‘roller-coaster’ period fertility trends (Hoem & Hoem, Reference Hoem and Hoem1996) have been combined with very stable cohort fertility that has stabilized close to 2 children per woman among the women born since 1910 (Fig. 6). These fertility swings have been partly driven by parental leave policies that stimulated a faster progression to second and higher order births (and thus higher fertility) in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Hoem & Hoem, Reference Hoem and Hoem1996), but also by economic downturns, changes in employment and education enrolment that led to postponed and depressed period TFRs, especially in the late 1990s (Andersson, Reference Andersson2000).

The key driving forces of post-transitional fertility

Four interrelated forces have been repeatedly identified as important explanations for the low, delayed and unstable period fertility in post-transitional countries: (1) the rapid growth in secondary and university education; (2) the rising instability of the labour market and the deteriorating economic position of young adults; (3) the changing gender roles and the concomitant rise of women’s employment, and 4) changing living arrangements and values related to partnership, marriage and family. Wide differences exist between countries in how they have accommodated to the sweeping changes in family behaviour. Given space limitations this discussion is simplified and omits many important details pertaining to specific countries and regions. A more detailed review is provided in Sobotka (Reference Sobotka2017).

This review would not be complete without mentioning the role of efficient contraception, especially the pill, but also of condoms, ‘emergency’ post-coital contraception and access to legal abortion. Widely used contraception has allowed the unprecedented fall in teenage fertility in most rich countries, has enabled women to pursue higher education without becoming pregnant and has allowed couples to postpone parenthood in response to adverse economic conditions (Goldin & Katz, Reference Goldin and Katz2002).

Education expansion as a key driver of postponed parenthood

The expansion of secondary and tertiary education, especially among women, has been the main factor behind the shift to delayed first birth (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Rindfuss, McDonald and te Velde2011; Ní Bhrolcháin & Beaujouan, Reference Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan2012). In the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries the share of 25- to 34-year-old women with tertiary education has clearly outpaced the rise of tertiary education among men of the same age (OECD, 2014a). In a growing number of countries, including Australia, Japan, South Korea, Sweden and the United Kingdom, a majority of women around age 30 have graduated from university. As being enrolled in education is usually considered incompatible with parenthood (Blossfeld & Huinink, Reference Blossfeld and Huinink1991), not least because it means delaying economic independence, the rise in university education directly translates into a later timing of first birth. In addition, young adults who have completed education now spend longer finding a stable job, leaving the parental home, finding a long-term partner and finding suitable housing. All these factors lead to additional postponement of family formation, a trend most pronounced among women with a degree (Lappegård & Rønsen, Reference Lappegård and Rønsen2005; Berrington et al., Reference Berrington, Stone and Beaujouan2015). Many women have been postponing childbearing considerably longer, into their late 30s or early 40s, risking infertility and often undergoing costly assisted reproduction treatments (Beaujouan & Sobotka, Reference Beaujouan and Sobotka2017).

The rise in education attainment is often linked to smaller family size. Most low-fertility countries, with the exceptions of Belgium and the Nordic countries (e.g. Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Rønsen, Knudsen, Lappegård, Neyer and Skrede2009), have a negative fertility gradient by level of education (Basten et al., Reference Basten, Sobotka and Zeman2014; Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Zeman, Potančoková, Eder, Brzozowska, Beaujouan and Matysiak2015). In addition, East Asian societies, especially Japan and South Korea, put strong emphasis on children’s education achievement, which is stressful, time-intensive and costly to the parents who pay for tutoring and other extracurricular activities. This ‘educational arms race’ arguably contributes to the ‘ultra-low’ fertility in the region (Rindfuss & Choe, Reference Rindfuss and Choe2015; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Morgan and Zagheni2016).

Uncertain lives: deteriorating economic and labour market position of young adults

The recent economic recession in Europe and the United States has provided new evidence that economically uncertain times are not conducive to marriage and childbearing (Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Skirbekk and Philipov2011). Business cycles clearly contribute to fertility fluctuations in post-transitional societies, especially through fertility downturns in uncertain times. However, the economic position of young adults – especially males – had started deteriorating in many rich countries several decades before the ‘Great Recession’ of 2008. Their employment rates declined (partly due to expanding university education), their jobs became more insecure and often poorly paid, their earnings relative to those of middle-aged people fell and housing became unaffordable for many of them (Blossfeld et al., Reference Blossfeld, Klijzing, Mills and Kurz2005; Sanderson et al., Reference Sanderson, Skirbekk and Stonawski2013; Economist, 2016). In particular, Southern European countries have seen a long-standing rise in labour market uncertainty among young adults, which imply postponement of marriage and family formation (Adsera, Reference Adsera2004, Reference Adsera2005; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Rindfuss, McDonald and te Velde2011), as an ever growing number of younger people are unable to reach the material standards (in terms of employment position, sufficient income and housing) considered necessary to start a family. The share of young adults who are NEETs (not in employment, education or training) has grown rapidly in the south and south-east of Europe, where it surpassed 15% in the early 2010s in several countries, including Italy and Spain (OECD, 2014b).

Scholars have pointed to a host of global and national forces behind young adults losing economic ground. These include economic liberalization and globalization of trade, migration of cheap labour competing with local blue-collar workers, technological change displacing lower-qualified jobs, but also social, pension and labour market policies that often ignore the needs of younger people. Vanhuysse (Reference Vanhuysse2013) has identified massive pro-elderly bias in public spending in many low-fertility OECD countries, including Poland, Greece, Italy, Slovakia and Japan.

The long-term trend towards more economic insecurity was recently aggravated in Europe and the United States by the impact of the recent Great Recession. This experience has generally confirmed that fertility in post-transitional countries is pro-cyclical (Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Skirbekk and Philipov2011; Currie & Schwandt, Reference Currie and Schwandt2014; Comolli, Reference Comolli2017). Fertility decline during the recent recession was especially sharp among young women below age 25, supporting the view that economic downturn typically leads to the postponement of births rather than to a decline in lifetime fertility.

Women’s employment and the ‘gender revolution’: from family decline to family resurgence?

The massive expansion of education among women has gone hand in hand with their rising career aspirations and actual employment rates. Being employed has become an expected part of women’s life plans in rich societies (Goldin, Reference Goldin2006). The indicator of women’s labour force participation, which also includes unemployed women, has broadly converged across the rich OECD countries (excluding Turkey and Latin American countries), typically reaching 70–85% among women aged 30–34 in 2014 (OECD, 2016). The upturns in women’s work participation have been most impressive in countries such as Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain, where a majority of women of childrearing ages (especially 25–45) remained outside formal employment until the 1980s. This shift in women’s education and labour market participation is also a marker of their ambitions and independence, which have profound implications for family life and fertility. In a nutshell, these implications can be summarized as follows:

-

1. The traditional male breadwinner model of family, characterized by gender role specialization and women’s almost exclusive responsibility for the domestic sphere, has rapidly diminished in importance. It has been replaced by more diverse family arrangements, including many households where a women has higher income than her male partner, but also by a rise of a ‘modernized male breadwinner model’ (Steiber et al., Reference Steiber, Berghammer and Haas2016), where mothers pursue part-time employment in order to be able to combine their parenting and childcare responsibilities.

-

2. Because a large majority of women expect to get employed after completing their education, parenthood is often postponed until a woman and her partner achieve relatively secure employment. This also implies that actual labour market experiences and employment expectations have a stronger influence on women’s fertility decisions than in the past.

-

3. Labour market conditions in terms of job security, unemployment rate, work hours, availability of part-time jobs, work flexibility and the availability of parental and childcare leave become increasingly important for women’s and couples’ fertility decisions. Rigid labour markets with long work hours, strong competition and little flexibility for employees, as in South Korea, contribute to delayed and depressed fertility. Similarly, poorly functioning labour markets with persistently high unemployment, high share of low-paid and unstable ‘stop-gap’ jobs, and also high rates of self-employment, as in Italy and Spain, have a similar negative effect (Adsera, Reference Adsera2004).

-

4. Family policies become important in mediating the impact of labour market conditions on families. Policies that support a combination of labour market involvement and family life also support women and couples in realizing their fertility plans. Of particular importance is the public provision of childcare, especially for children below age 3, and policies regulating parental leave and employment.

-

5. The contribution of men to childcare and household responsibilities is increasingly relevant (Hook, Reference Hook2006; Miranda, Reference Miranda2010). In countries where an unequal division of household tasks persists and women shoulder the double burden of employment and family responsibilities, the consequence for fertility decisions is obvious: having fewer children and having them later in life. Especially in East Asia, men mostly focus on their work career and contribute very little time to childcare and domestic work (e.g. Tsuya, Reference Tsuya2015, for Japan).

-

6. High level of domestic gender equality has been repeatedly suggested as a pre-condition to achieving higher fertility rates in post-transitional countries (e.g. McDonald, Reference McDonald2000; Goldscheider et al., Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015). Myrskylä et al. (Reference Myrskylä, Kohler and Billari2011) concluded that countries that combined advanced development (high education, high income and low mortality) and low level of gender equality were characterized by declining or very low fertility. This evidence lends support to the notion that countries with pronounced domestic gender inequality might indeed get ‘stuck’ at a low fertility level for prolonged periods of time (Goldscheider et al., Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015).

The link between changing values, changing family and fertility

The most prominent theoretical framework of post-transitional fertility and family change is the concept of the ‘Second Demographic Transition’ (SDT) (e.g. van de Kaa, Reference Van de Kaa1987; Lesthaeghe, Reference Lesthaeghe2010). The framework links changes in values and changes in family – characterized by a decline in marriage and a rise in cohabitation, living single and other less ‘traditional’ family forms – with a concomitant fertility decline to sub-replacement levels and parenthood postponement (Lesthaeghe, Reference Lesthaeghe2010). But there is an interesting and initially unexpected twist. Most European countries that progressed furthest in values shifts and family behaviours characteristic of the SDT, including the Nordic countries and France, did not experience fertility declines to very low levels (Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2008). These countries combine a pattern of postponed parenthood with a strong ‘recovery’ of fertility rates at advanced reproductive ages.

One factor that may contribute to this fertility recovery is the high level of gender equality discussed above: the ‘gender revolution’ clearly progresses hand in hand with the SDT. In addition, the positive SDT–fertility correlation is also partly explained by a wide acceptance of cohabitation and fertility outside marriage in countries where SDT has advanced most. There, fertility outside marriage has at least partly offset the fall in marital fertility. It is therefore no coincidence that close-to-replacement fertility is positively correlated with a high share of births outside marriage. In a growing number of European countries, including Belgium, France and Sweden, a majority of births take place outside marriage, rendering marriage ever more irrelevant for fertility.

In many societies, however, the declining relevance of marriage has gone hand in hand with prolonged single living or extended co-residence of young adults with their parents. In East Asia, childbearing outside marriage remains strongly disapproved of. At the same time, the ‘marriage package’ for women is still often bundled not only with childbearing and childrearing, but also with a long withdrawal from employment and with many new family responsibilities (see Bumpass et al., Reference Bumpass, Rindfuss, Choe and Tsuya2009). In Southern Europe, a mixture of prolonged education, precarious economic situation and unaffordable housing, combined with the persistence of strong family ties, has resulted in a high share of young people who continue living with their parents (and enjoying all the amenities of ‘hotel mamma’) well into their 30s (Iacovou, Reference Iacovou2010). A similar situation also persists in many countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2011).

Discussion

The empirical findings on the experiences of post-transitional societies presented in this study can be summarized in ten key messages:

-

1. Period fertility decline in most post-transitional countries continues once the threshold of replacement fertility is crossed. In addition, there is no obvious theoretical or empirical threshold around which the period fertility should stabilize. A number of countries briefly achieved extreme low period TFR at around 1.0 or below and the question of ‘how low can fertility fall?’ (Golini, Reference Golini1998) remains open.

-

2. Post-transitional fertility is often unstable, at least when measured in a period perspective, as women and couples react to the ups and downs of the labour market, changing economic conditions, education opportunities, changing family policies and other factors that affect their fertility decisions.

-

3. Post-transitional countries and regions display a wide range of fertility levels, with period TFRs varying from below one to above-replacement levels. Even within one country, such as Russia, there may be regions with very low fertility and other with high fertility rates well above replacement level (Fig. 2).

-

4. Period fertility can also go up, and these upturns are often unexpected and strong, as in the case of eastern Germany, which saw its period TFR double from below 0.8 in 1994 to above 1.5 two decades later.

-

5. There is no low-fertility threshold that would make future recovery of fertility unlikely if not impossible. This analysis clearly shows that societies reaching very low period fertility levels do not necessarily get ‘locked in’ ultra-low fertility for long. However, some countries show a combination of cultural, economic and social conditions that make sustained fertility increases difficult to achieve.

-

6. Whereas post-transitional fertility usually does not stabilize at the replacement level, post-transitional fertility ideals and intentions often do. The experience of generally low and often unstable fertility contrasts with family size ideals and intentions that are often stable and closely clustered around or slightly above two children in most countries of Europe, in the United States, Canada and Australia, but also in Japan and South Korea (Hagewen & Morgan, Reference Hagewen and Morgan2005; Edmonston et al., Reference Edmonston, Lee and Wu2010; Fukuda et al., Reference Fukuda, Kaneko and Moriizumi2013; Sobotka & Beaujouan, Reference Sobotka and Beaujouan2014).

-

7. Most post-transitional societies have seen a long-lasting shift towards delayed parenthood, with a majority of women in some countries becoming mothers after age 30. The observed shift fits well the ‘postponement transition’ framework elaborated by Kohler et al. (Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002).

-

8. The ‘postponement transition’ results in a prolonged stage of depressed, and often very low, period fertility levels. This stage typically lasts several decades, followed by at least a partial ‘recuperation’ of period fertility rates, linked with the diminishing pace of fertility postponement. The dynamics of the transition and the extent of fertility ‘recuperation’ vary widely between countries (Frejka, Reference Frejka2012).

-

9. Tempo distortions in period fertility during the ‘postponement transition’ imply that conventional period fertility measures provide partial and often misleading understanding of fertility trends (Sobotka & Lutz, Reference Sobotka and Lutz2011; Bongaarts & Sobotka, Reference Bongaarts and Sobotka2012). The solution lies in using both cohort fertility indicators – which are relatively smooth and undistorted by fertility postponement – and more sophisticated period indicators, which are less affected by the shifts in the timing of births.

-

10. Cohort fertility may remain stable and close to replacement. In contrast to conventional period indexes, cohort fertility indicators actually show that lifetime fertility in a number of post-transitional societies has stabilized close to the replacement level threshold.

The forces fuelling fertility change, discussed above, may in combination speed up or prevent the shift to very low fertility levels. In addition, family policies become important in helping women and men to reconcile their employment and career with their family life, and limit the negative consequences of having children on their well-being (OECD, 2011). While the impact of individual policy instruments on fertility is difficult to quantify, the combination of different policies may nurture institutional conditions supportive of fertility (Luci-Greulich & Thévenon, Reference Luci-Greulich and Thévenon2013). However, many governments take a narrow and instrumental view of family policies, enacting pronatalist measures that fail to take into account the new reality of more equal gender roles, more diverse family forms and high career aspirations among women. Such policies frequently support the male breadwinner model and tend to focus on financial incentives for childbearing (see Rivkin-Fish, Reference Rivkin-Fish2010, for Russia). In addition, family policies often suffer from frequent changes and reversals, fostering unpredictability and uncertainty among prospective parents, as discussed by Spéder (Reference Spéder2016) on the example of Hungary.

The future ‘postponement transition’ in middle-income countries

Are these findings, based on the experiences of rich countries with a long history of sub-replacement fertility, also relevant for middle-income countries approaching the final stage of their fertility transition? The answer is clearly positive, although regional differences in culture, education systems, policies and family patterns will foster considerable variation in post-transitional fertility trends.

Countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, South-east Asia and Southern Asia (including India and China), richer parts of Western Asia (especially Iran and Turkey), as well as parts of Central Asia, Northern Africa and Southern Africa, are likely to experience extended sub-replacement period fertility and the concomitant shift towards later childbearing over the coming decades. If this envisioned effect takes place, it has the capacity to foster many of the social and economic challenges long faced by ageing European societies: it will bring about accelerated population ageing, often resulting in stagnating or shrinking population and labour force size, and will lead to a swift refocusing of social and family policies. As a sign of these shifts already under way, a number of middle-income countries have seen their governments scrapping previously antinatalist policies (most prominent was China’s recent abandonment of enforced one-child policies) or promoting an openly pronatalist policy agenda (e.g. in Iran and Turkey; for Iran see McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Hosseini-Chavoshi, Abbasi-Shavazi and Rashidian2015).

The argument about the likely future below-replacement fertility in countries nearing the end of their fertility transition is neither new nor surprising. Following the earlier experience of highly developed post-transitional societies, fertility projections produced by the United Nations as well as by national statistical agencies in Brazil, China, Iran, Mexico and Turkey now envision that low fertility will persist for many decades to come (Sobotka et al., Reference Sobotka, Gietel-Basten and Zeman2016). However, population researchers and policy experts in these countries often remain unaware of the role of the ‘postponement transition’ in driving fertility in parts of the developed world to very low levels and the potential for such a tempo shift to influence period fertility trends in their societies (Bongaarts, Reference Bongaarts1999). Far too often, TFR continues being the only regularly assessed indicator of fertility, falsely interpreted as if it were a cohort measure of actual family size. This often hinders understanding of the ongoing fertility decline and causes unnecessary concern about women having too small a family size in countries such as Iran and Turkey (e.g. McDonald, 2015).

The forces that have driven the shift towards lower and later fertility in the post-transitional countries are also becoming prominent in middle-income countries with more recent fertility declines. The rapid economic growth experienced in the 2000s and early 2010s in much of Asia and Latin America has helped lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and has contributed to the nascent rise of the middle class (Kochhar, Reference Kochhar2015), which is predicted to grow rapidly in the coming decades (Kharas, Reference Kharas2011). These improvements in living standards will in turn contribute to the trend of having fewer, but better educated children. Such a reorientation is also made possible by a continuing rise in contraceptive use among women in developing countries (Alkema et al., Reference Alkema, Kantorová, Menozzi and Biddlecom2013). Middle-income countries are also experiencing an expansion of higher education, a key factor behind delayed childbearing. For instance, most Asian countries saw a rapid increase in the enrolment in tertiary education in the 1990s and 2000s, with the Philippines, Iran and Thailand reaching an enrolment ratio in bachelor’s programmes of over 25% in 2011 (UNESCO, 2014, Fig. 1). Similarly to the most developed countries, the rise of tertiary education has been faster for women, whose enrolment has surpassed that among men in an increasing number of Asian countries including China, Malaysia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka (UNESCO, 2014, Fig. 7).

Young adults in middle-income countries, especially in the Middle East and North Africa, but also in Latin America, face extended periods of unemployment and economic uncertainty, similar to the experience of younger people in Southern Europe. Research on Latin America by Adsera and Menedez (Reference Adsera and Menendez2009) showed that women tend to postpone or reduce fertility in times of rising unemployment, which is in line with the findings for rich countries. There is also ample evidence on family changes, although their character varies widely across countries and regions. Esteve et al. (Reference Esteve, Lesthaeghe and López‐Gay2012) showed a rapidly rising prevalence of unmarried cohabitation in Latin America, especially in countries where cohabitation used to be uncommon, including Brazil. In many parts of Latin America, the fertility rates of married and cohabiting unions have become similar, with marriage no longer being key for reproduction (Laplante et al., Reference Laplante, Castro‐Martín, Cortina and Martín‐García2015). In China, where childbearing outside marriage remains rare, a rapid rise in premarital cohabitation has been documented for the younger cohorts, especially among the economically advantaged segments of population (Yu & Xie, Reference Yu and Xie2015). In many countries where cohabitation is not normatively accepted, population surveys show a strong postponement of marriage and the rise of lifetime singlehood and childlessness, especially among higher educated women who do not want to enter the traditional ‘marriage package’ and among poorly educated men who cannot afford to marry. For instance, census data and surveys in countries of North Africa, including Algeria, Libya and Tunisia, indicate a massive postponement of marriages between the 1970s and 2000s, with the mean age at first marriage among women reaching or surpassing 30 (Ouadah-Bedidi et al., Reference Ouadah-Bedidi, Vallin and Bouchoucha2012).

In the last three decades many middle-income countries from Brazil through China to Thailand and Vietnam have joined the ranks of below-replacement fertility settings. The evidence on the nascent ‘postponement transition’ remains more scattered, in part because the data on the timing of first births are less readily available, and in part because this process has been building up only gradually. The study by Bongaarts (Reference Bongaarts1999) was the first to suggest that period fertility rates in many less-developed countries are, at least to a small extent, affected by the changes in the timing of births. Since then, the emerging shift towards delayed childbearing, especially among highly educated women, has been documented for Latin America (Rosero-Bixby et al., Reference Rosero-Bixby, Castro-Martín and Martín-García2009; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Pardo and Cabella2016; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Zeman, Castro, Nathan and Sobotka2017), China (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Zhigang and Hayford2009), India (Spoorenberg, Reference Spoorenberg2010) and indirectly, through delayed marriages, in Iran in the 1990s (Hosseini-Chavoshi et al., Reference Hosseini-Chavoshi, McDonald and Abbasi-Shavazi2006; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Hosseini-Chavoshi, Abbasi-Shavazi and Rashidian2015) and North Africa (Ouadah-Bedidi et al., Reference Ouadah-Bedidi, Vallin and Bouchoucha2012).

The widespread shift to delayed parenthood in rich countries constitutes a unique experience in human history when most of the younger women and men spend their peak reproductive years sexually active, but consistently and effectively avoiding reproduction. The future ‘postponement transitions’ will vary between countries and their progression will often diverge from the earlier experiences in Europe and elsewhere. In particular, the evidence to date suggests that the future shift towards delayed childbearing might be slower in many countries. In Latin America and the Caribbean a slower shift towards delayed motherhood could be linked to persistently high rates of teenage childbearing and frequent unwanted pregnancies, especially among lower-educated women (Rosero-Bixby et al., Reference Rosero-Bixby, Castro-Martín and Martín-García2009; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Pardo and Cabella2016). In other settings where early marriage and motherhood remain strongly valued, fertility postponement may primarily occur via rising birth intervals, especially between the first and the second birth. Such trends have been documented for China (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Zhigang and Hayford2009) and Iran (Hosseini-Chavoshi et al., Reference Hosseini-Chavoshi, McDonald and Abbasi-Shavazi2006; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Hosseini-Chavoshi, Abbasi-Shavazi and Rashidian2015). Some countries with distinct ethnic or religious minorities may follow the pattern of Israel, where a sizeable minority continues exhibiting very high (and early) fertility, keeping the overall fertility in the country relatively high and stable even when most women delay parenthood to higher ages. Furthermore, government policies promoting marriage and childbearing may temporarily slow down or even reverse the ‘postponement transition’ in countries where policymakers become too concerned about falling marriage and birth rates. At the same time, the huge potential of delayed childbearing for temporarily depressing the period fertility rates – and thus also the number of births – can be explored in population policies by the governments trying to slow down population growth. Matthews et al. (Reference Matthews, Padmadas, Hutter, McEachran and Brown2009: Table 4) showed that in India alone, a shift to later marriage and childbearing could reduce the number of births and population size by tens of millions by 2050.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant agreement No. 284238 (EURREP Project). Many thanks go to Éva Beaujouan, who commented on an earlier draft of this paper, and to Chris Wilson and Sasee Pallikadavath, who have shown remarkable patience and encouragement during the long preparation of this paper. An extended version of this article is available as a working paper (Sobotka, Reference Sobotka2017).