Article contents

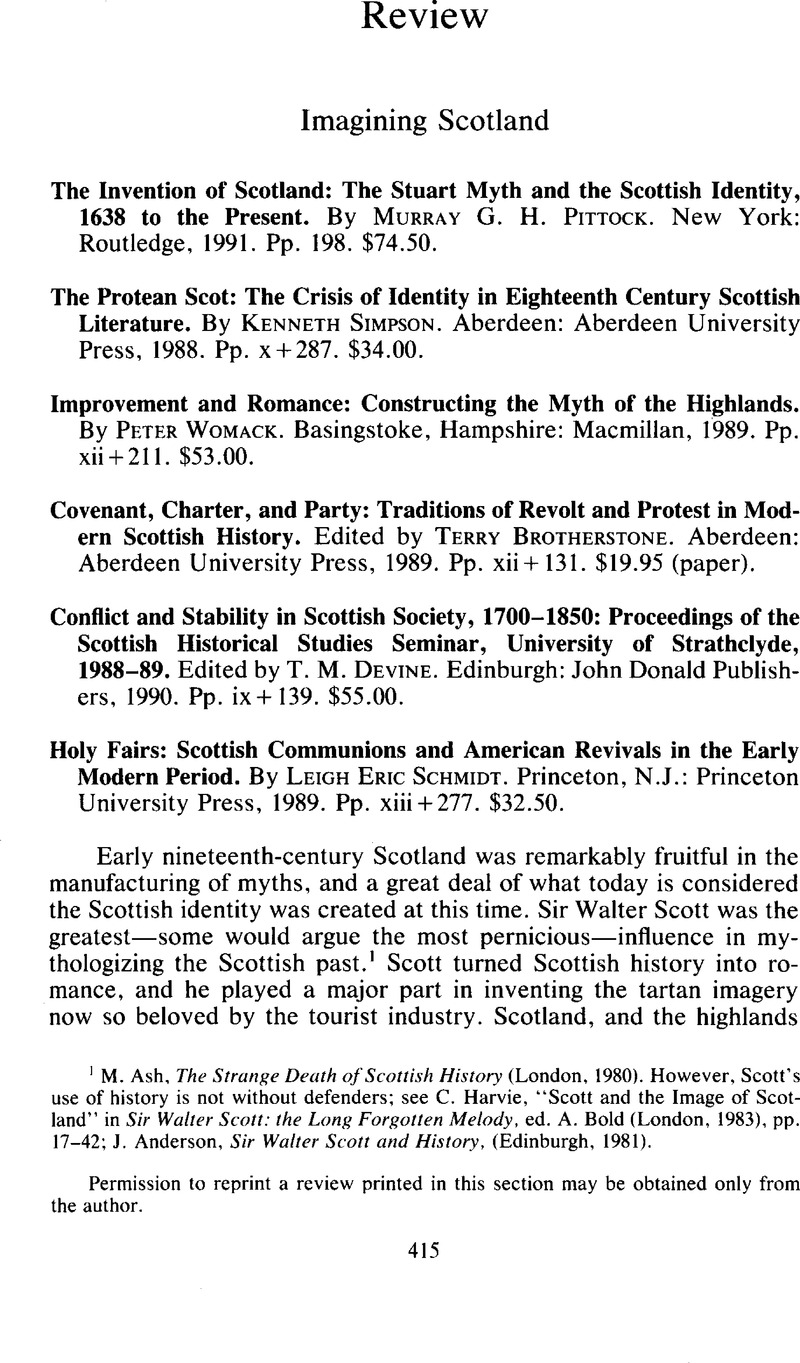

Imagining Scotland - The Invention of Scotland: The Stuart Myth and the Scottish Identity, 1638 to the Present. By Murray G. H. Pittock. New York: Routledge, 1991. Pp. 198. $74.50. - The Protean Scot: The Crisis of Identity in Eighteenth Century Scottish Literature. By Kenneth Simpson. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988. Pp. x + 287. $34.00. - Improvement and Romance: Constructing the Myth of the Highlands. By Peter Womack. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1989. Pp. xii + 211. $53.00. - Covenant, Charter, and Party: Traditions of Revolt and Protest in Modern Scottish History. Edited by Terry Brotherstone. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1989. Pp. xii + 131. $19.95 (paper). - Conflict and Stability in Scottish Society, 1700–1850: Proceedings of the Scottish Historical Studies Seminar, University of Strathclyde, 1988–89. Edited by T. M. Devine. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, 1990. Pp. ix + 139. $55.00. - Holy Fairs: Scottish Communions and American Revivals in the Early Modern Period. By Leigh Eric Schmidt. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989. Pp. xiii + 277. $32.50.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Review

- Information

- Journal of British Studies , Volume 31 , Issue 4: Britishness and Europeanness: Who Are the British Anyway? , October 1992 , pp. 415 - 425

- Copyright

- Copyright © North American Conference of British Studies 1992

References

1 Ash, M., The Strange Death of Scottish History (London, 1980)Google Scholar. However, Scott's use of history is not without defenders; see Harvie, C., “Scott and the Image of Scotland” in Sir Walter Scott: the Long Forgotten Melody, ed. Bold, A. (London, 1983), pp. 17–42Google Scholar; Anderson, J., Sir Walter Scott and History, (Edinburgh, 1981)Google Scholar.

2 The best political studies of the making of the union are P. W. J. Riley, The Union of Scotland and England (Manchester, 1978); and W. Ferguson, Scotland's Relations with England: A Survey to 1707 (Edinburgh, 1977). The weight of recent evidence decisively has come down on the side of short-term political wheeling and dealing as the principal explanation for why the Scots agreed to union. Consequently, the argument for long-term economic causes, advocated principally by T. C. Smout in Scottish Trade on the Eve of Union (Edinburgh and London, 1963), has been dented severely. However, economic issues have been reintroduced to the debate by C. A. Whatley, “Salt, Coal and the Union of 1707: A Revision Article,” Scottish Historical Review (SHR) 66 (1987): 26-45, “The Economic Causes and Consequences of the Union of 1707: A Survey,” SHR 68 (1989): 150-81.

3 Campbell, R. H., Scotland since 1707 (London, 1971)Google Scholar, took the view that union provided the environment for long-term economic growth. However, recent research has drawn more ambivalent conclusions; see Devine, T. M., “The Union of 1707 and Scottish Development,” Scottish Economic and Social History 5 (1985): 23–40CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Whatley, “Economic Causes and Consequences of the Union.” Even Professor Smout is less sure than before; see Smout, T. C., “Where Had the Scottish Economy Got to by the Third Quarter of the 18th Century?” in Wealth and Virtue: The Shaping of Political Economy in the Scottish Enlightenment, ed. Hont, I. and Ignatieff, M. (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 45–72CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 For example, Riley, pp. 220–45. However, there has been some attempt to investigate the pamphlet war as a genuine clash of ideas by Robertson, J., “Andrew Fletcher's Vision of Union,” in Scotland and England, 1286–1815, ed. Mason, R. A. (Edinburgh, 1987), pp. 203–25Google Scholar.

5 Mason, R. A., “Scotching the Brut: Politics, History and National Myth in Sixteenth Century Britain,” in Mason, , ed., pp. 60–84Google Scholar; Williamson, A. H., Scottish National Consciousness in the Age of James VI (Edinburgh, 1979)Google Scholar; Stevenson, D., “The Early Covenanters and the Federal Union of Britain,” in Mason, , ed., pp. 163–81Google Scholar.

6 Newman, G., The Origins of English Nationalism (London, 1987)Google Scholar.

7 The best introduction to the jacobites is Lenman, B., The Jacobite Risings in Britain (London, 1980)Google Scholar. The importance of jacobitism to eighteenth-century politics and culture is certain to be raised yet further by the evidence presented in Monod, P., Jacobitism and the English People, 1688–1788 (Cambridge, 1989)Google Scholar.

8 On this theme, see Donaldson, W., The Jacobite Song: Political Myth and National Identity (Aberdeen, 1988)Google Scholar; Pittock, M. G. H., New Jacobite Songs of the Forty-five (Oxford, 1989)Google Scholar.

9 Pittock, , The Invention of Scotland, p. 89Google Scholar.

10 The debate over the origins of the Scottish enlightenment revolves around the question of the extent to which the enlightenment was distinctively Scottish and had its roots in the seventeenth-century inheritance and how far it was either a reaction to or consequence of union. See Withrington, D. J., “What Was Distinctive about the Scottish Enlightenment?” in Aberdeen and the Enlightenment, ed. Carter, J. and Pittock-Wesson, J. (Aberdeen, 1987), pp. 9–19Google Scholar; Daiches, D., The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth Century Experience (Oxford, 1964)Google Scholar; Camic, C., Experience and Enlightenment: Socialisation for Cultural Change in Eighteenth Century Scotland (Edinburgh, 1983)Google Scholar; Campbell, R. H. and Skinner, A. S., eds., The Origins and Nature of the Scottish Enlightenment (Edinburgh, 1982)Google Scholar; Chitnis, A. C. C., The Scottish Enlightenment: A Social History (London, 1976)Google Scholar; Phillipson, N. T., “The Scottish Enlightenment,” in The Enlightenment in National Context, ed. Porter, R. and Teich, M. (Cambridge, 1981), pp. 19–40CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Rendall, J., The Origins of the Scottish Enlightenment, 1707–1776 (London, 1978)Google Scholar.

11 Essentially, this debate is about the degree of Anglicization; see Phillipson, N. T., “Politics, Politeness and the Anglicisation of Early Eighteenth-Century Scottish Culture,” in Mason, , ed., pp. 226–46Google Scholar; Smout, T. C., “Problems of Nationalism, Identity and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scottish Culture,” in Improvement and Enlightenment, ed. Devine, T. M. L. (Edinburgh, 1989), pp. 1–21Google Scholar; Mitchison, R., “Nineteenth Century Scottish Nationalism: The Cultural Background,” in The Roots of Nationalism: Studies in Northern Europe, ed. Mitchison, R. (Edinburgh, 1980), pp. 131–42Google Scholar.

12 Dwyer, J., Virtuous Discourse: Sensibility and Community in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Edinburgh, 1987)Google Scholar; and McGurk, C., Robert Burns and the Sentimental Era (Athens, 1985)Google Scholar, explore themes related to the development of the sentiment movement.

13 For an introduction to the highland problem, see Stevenson, D., Alasdair Mac-Colla and the Highland Problem in the Seventeenth Century (Edinburgh, 1980), pp. 6–33Google Scholar. A useful analysis of highland culture is Dodgshon, R. A., “‘Pretense of Blude’ and ‘Place of Thair Dwelling’: The Nature of Highland Clans, 1500–1745,” in Scottish Society, 1500–1800, ed. Houston, R. A. and Whyte, I. D. (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 169–98CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

14 Mitchison, R., “The Government and the Highlands, 1707–1745,” in Scotland in the Age of Improvement: Essays in Scottish History in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Phillipson, N. T. and Mitchison, R. (Edinburgh, 1970), pp. 24–46Google Scholar; Lenman, B. P., The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746 (London, 1980)Google Scholar, The Jacobite Clans of the Great Glen, 1650–1784 (London, 1984)Google Scholar; Hopkins, P., Glencoe and the End of the Highland War (Edinburgh, 1986)Google Scholar.

15 Smith, A., Jacobite Estates after the Forty-five (Edinburgh, 1982)Google Scholar; Youngson, A. J., After the Forty-five: The Economic Impact on the Scottish Highlands (Edinburgh, 1973)Google Scholar.

16 Trevor-Roper, H., “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland,” in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Hobsbawm, E. and Ranger, T. (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 15–43Google Scholar.

17 Hechter, M., Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1536–1966 (London, 1975)Google Scholar.

18 Gregeen, E., “The Changing Role of the House of Argyll in the Scottish Highlands,” in Phillipson, and Mitchison, , eds., pp. 5–23Google Scholar.

19 On the whole, this has concentrated on the highland clearances; see Macinnes, A. I., “Scottish Gaeldom: The First Phase of Clearance,” in People and Society in Scotland, vol. 1: c. 1760–1830, ed. Devine, T. M. and Mitchison, R. (Edinburgh, 1988), pp. 70–90Google Scholar; Richards, E., A History of the Highland Clearances, 2 vols. (London, 1982, 1985)Google Scholar. For a more positive interpretation of the clearances, see Bumsted, J. M., The People's Clearance, 1700–1815 (Edinburgh, 1982)Google Scholar. Another theme of highland culture has been the question of language, which has received significant attention in recent years, see Withers, C. W. J., Gaelic in Scotland, 1689–1981: The Geographical History of a Language (Edinburgh, 1984)Google Scholar.

20 Young, J. D., The Rousing of the Scottish Working Class (London, 1981), pp. 11–71Google Scholar.

21 Macinnes, A. I., Charles I and the Making of the Covenanting Movement, 1625–1641 (Edinburgh, 1991)Google Scholar; Makey, W., The Church of the Covenant, 1637–1651 (Edinburgh, 1979)Google Scholar.

22 Fora more full treatment of this period, see Cowan, I. B., The Scottish Covenanters, 1660–88 (London, 1976)Google Scholar. However, the later covenanters still require full analysis of their ideas, organization, and support.

23 The deliberate rejection by the aristocracy of political radicalism has perhaps been overstated, but for a strong defense of pragmatic conservatism, see Lenman, B. P., “The Scottish Nobility and the Revolution of 1688–1690” in The Revolutions of 1688, ed. Beddard, R. (Oxford, 1991), pp. 137–62Google Scholar, “The Poverty of Political Theory in the Scottish Revolution, 1689–90” in The Glorious Revolution, 1688–89, ed. Schwoerer, L. G. (Cambridge, 1992)Google Scholar. The toleration act primarily was a product of party politics; see Szechi, D., “The Politics of ‘Persecution’: Scots Episcopalian Toleration and the Harley Ministry, 1710–12,” Studies in Church History 21 (1984): 275–87CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

24 For some case studies, see Muirhead, A. T. N., “A Secession Congregation in the Community: The Stirling Congregation of Rev Ebeneezer Erskine,” Records of the Scottish Church History Society (RSCHS) 22 (1986): 211–32Google Scholar; Sher, R. B., “Moderates, Managers and Popular Politics in Mid-eighteenth Century Edinburgh: The Drysdale ‘Bustle’ of the 1760s,” in New Perspectives on the Politics and Culture of Early Modern Scotland, ed. Dwyer, J., Mason, R. A. and Murdoch, A. (Edinburgh, 1982), pp. 179–209Google Scholar; Morrell, J. B., “The Leslie Affair: Careers, Kirk and Politics in Edinburgh, 1805,” SHR 54 (1975): 63–82Google Scholar. On the political uses of patronage, see Sefton, H. R., “Lord Islay and Patrick Cuming: A Study in Eighteenth-Century Ecclesiastical Management,” RSCHS 19 (1977): 203–16Google Scholar; Sher, R. and Murdoch, A., “Patronage and Party in the Church of Scotland, 1750–1800,” in Church, Politics and Society: Scotland, 1408–1929, ed. Macdougall, N. (Edinburgh, 1983), pp. 197–220Google Scholar.

25 A fuller account of Brown's views are found in Brown, C. G., The Social History of Religion in Scotland since 1730 (London and New York, 1987)Google Scholar.

26 Brims, J. D., “The Scottish ‘Jacobins’, Scottish Nationalism and the British Union,” in Mason, , ed. (n. 4 above), pp. 247–65Google Scholar.

27 For earlier work on riots, see Logue, K., Popular Disturbances in Scotland, 1780–1815 (Edinburgh, 1979)Google Scholar; Lythe, S. G. E., “The Tayside Meal Mobs, 1772–3,” SHR 46 (1967): 26–36Google Scholar.

28 The aristocratic domination of Scottish politics and society in the eighteenth century was overwhelming. For the system of management that operated see Ferguson, W., Scotland: 1689 to the Present (1968; reprint, Edinburgh, 1975), pp. 133–65Google Scholar; Murdoch, A., The People Above: Politics and Administration in Mid-18th Century Scotland (Edinburgh, 1980)Google Scholar; Shaw, J. S., The Management of Scottish Society, 1707–1764: Power, Nobles, Lawyers, Edinburgh Agents and English Influences (Edinburgh, 1983)Google Scholar; Sunter, R. M., Patronage and Politics in 18th and Early 19th Century Scotland (Edinburgh, 1986)Google Scholar; Whetstone, A. E., Scottish County Government in the 18th and 19th Centuries (Edinburgh, 1981)Google Scholar. On their economic wealth and influence, see Smout, T. C., “Scottish Landowners and Economic Growth, 1650–1850,” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 11 (1964): 218–34Google Scholar; Soltow, L., “Inequality and Wealth in Land in Scotland in the Eighteenth Century,” Scottish Economic and Social History 10 (1990): 38–60CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Timperley, L., “The Pattern of Landholding in Eighteenth-Century Scotland,” in The Making of the Scottish Countryside, ed. Parry, M. L. and Slater, T. R. (London, 1980), pp. 137–54Google Scholar.

29 The Scottish middle classes have received comparatively little study, but see Nenadic, S., “The Rise of the Urban Middle Class,” in Devine, and Mitchison, , eds. (n. 19 above), pp. 109–26Google Scholar. Before ca. 1760, the middling orders were to be found among the merchants and in the legal profession; see Devine, T. M., “The Scottish Merchant Community, 1680–1740,” in Campbell, and Skinner, (n. 10 above), pp. 26–41Google Scholar; Phillipson, N. T., “Lawyers, Landowners and the Civic Leadership of Post-union Scotland,” Juridical Review, n.s., 21 (1976): 97–120Google Scholar, “The Social Structure of the Faculty of Advocates in Scotland, 1661–1840,” in Law-making and Law-Makers in British History, ed. Harding, A. (London, 1980), pp. 145–56Google Scholar.

30 On this theme, see Fraser, W. H., Conflict and Class: Scottish Workers, 1700–1838 (Edinburgh, 1988)Google Scholar.

31 This was a theme of Drummond, A. L. and Bulloch, J., The Scottish Church, 1688–1843 (Edinburgh, 1973)Google Scholar. See, too, Smout, T. C., A History of the Scottish People, 1560–1830 (London, 1981), pp. 213–22Google Scholar.

32 Clark, I. D. L., “From Protest to Reaction: The Moderate Regime in the Church of Scotland, 1752–1805,” in Phillipson, and Mitchison, , eds. (n. 14 above), pp. 200–224Google Scholar; Dwyer, J., “The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Divines,” in Dwyer, et al., eds., pp. 291–318Google Scholar; Sefton, H., “‘Neu-lights and preechers legall’: Some Observations on the Beginnings of Moderatism in the Church of Scotland,” in Macdougall, , ed., pp. 186–96Google Scholar; Sher, R., Church and University in the Scottish Enlightenment: The Moderate Literati of Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 1985), pp. 141–57Google Scholar.

- 1

- Cited by