No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

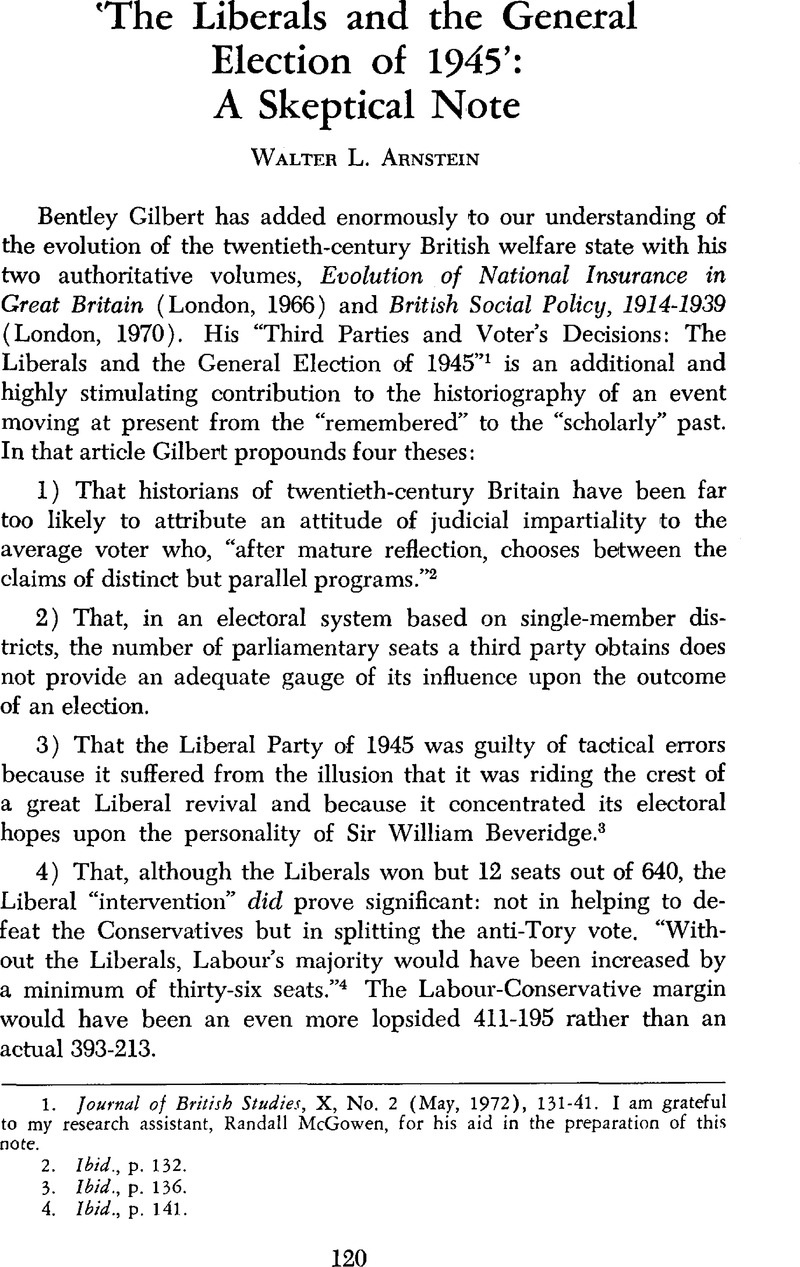

‘The Liberals and the General Election of 1945’: A Skeptical Note

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © North American Conference of British Studies 1975

References

1. Journal of British Studies, X, No. 2 (May, 1972), 131–41Google Scholar. I am grateful to my research assistant, Randall McGowen, for his aid in the preparation of this note.

2. Ibid., p. 132.

3. Ibid., p. 136.

4. Ibid., p. 141.

5. Human Nature in Politics (London, 1908)Google Scholar, Ch. I.

6. Laing, Lionel H. makes the same observation about the 1950 election in Pollack, James K.et al, British Election Studies (Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1951), pp. 114–25Google Scholar.

7. Cited in Butler, David and Freeman, Jennie (eds.), British Political Facts 1900-1967, (2nd ed.; London, 1968), p. 159Google Scholar.

8. Kinnear, Michael, The British Voter: An Atlas and Survey Since 1885 (Ithaca, New York, 1968), p. 55Google Scholar.

9. Butler, and Freeman, , British Political Facts, p. 161Google Scholar.

10. Gilbert, , “Third Parties”, J. B. S., X (1972), 138Google Scholar.

11. Ibid.

12. Although the conventional wisdom assumes that the Labour Party as it grew during the 1920s was made up primarily of ex-Liberal supporters, David Butler and Donald Stokes have provided persuasive evidence that Liberal voters were more likely, by a 4-3 ratio, to turn Conservative than Labour. The growing Labour vote was drawn largely from a new generation of voters that was first enfranchised or first came of age in 1918 or during the 1920s. See Political Change in Britain (London, 1969), pp. 251–52Google Scholar. Although Gilbert argues that the ratio of Conservative seats retained “increased as the Liberal vote increased,” could one not equally maintain that the Liberals tended to do best where the Conservatives did best because the two parties appealed ultimately to the same (or, at least, an overlapping) portion of the electorate?

13. See The Economist, 4 Aug. 1945, pp. 150–51Google Scholar, and Times (London) 27 July, 1945Google Scholar. See also the letter columns of the Times, 30 July 1945, and 1, 3, 4 Aug. 1945. Even before the results were in, the Times reported “some anxiety on the Government side about the results which the large-scale Liberal intervention may have had in many of the constituencies where there were three-cornered fights.” 10 July 1945.

14. Marquand, David, “Can Labour Recover?” Encounter, XIX No. 4 (Oct., 1962), 57Google Scholar. The same prospect was foreseen in “New Vintage Liberalism,” Political Quarterly, XXXIII, No. 3 (July-Sept., 1962), 233, 246Google Scholar.

15. Gilbert, , “Third Parties”, J. B. S., X, 137fGoogle Scholar. According to a Gallup Poll of 1949, of those electors who had voted Liberal in 1945 only 57 percent intended to vote Liberal at the forthcoming election. 25 percent had defected to the Conservatives, and 9 percent to Labour. Inasmuch as there was movement in the opposite direction as well, the percentage of the total Liberal popular vote in 1950 was almost identical to that of 1945. “… It seems reasonably clear,” concluded Peter Jenkin at the time, “that a Conservative Government could have been formed had there been only one-third as many Liberal candidates as there actually were in the 1950 election.” See Pollock, James K.et al, British Election Studies, pp. 18, 58Google Scholar.

16. Kinnear, , British Voter, pp. 58, 60Google Scholar. David Butler suggests that the number of Liberals who actually abstained from voting in 1951 in constituencies in which no Liberal was standing was nearer 10 percent than 35 percent. The tendency of ex-Liberals to vote Conservative, according to Butler's estimate, accounted for at least 8 and possibly as many as 18 of the 24 seats that the Conservatives won from Labour. Conversely, 5 of the 6 victorious Liberals had no Conservative opposition. The British General Election of 1951 (London, 1952), pp. 239–44Google Scholar.

17. Butler, and Freeman, , British Political Facts, p. 143Google Scholar.

18. McKenzie, Robert, “Between Two Elections,” Encounter, XXVI, No. 1 (Jan., 1966), 12Google Scholar.

19. Political Change in Britain, pp. 318-19. The dramatic electoral shift between 1970 and 1974 illustrates the same pattern, i.e. yet another Labour “victory” made possible by a Liberal resurgence: (Percent)

20. Cf. Douglas, Roy, A History of the Liberal Party, 1895-1970 (London, 1971), pp. xi-xii, 243–47Google Scholar.

21. Cited in Cantril, Hadley (ed.), Public Opinion, 1935-1946 (Princeton, 1951), p. 198Google Scholar.

22. Ibid., p. 197, cited in Gilbert, , “Third Parties”, J. B. S., X, 137 f.Google Scholar

23. Cf. Rasmussen, Jorgen Scott, Retrenchment and Revival: A Study of the Contemporary British Liberal Party (Tucson, Arizona, 1964), pp. 10–11Google Scholar; SirJennings, Ivor, Party Politics, I (Cambridge, 1960), 285, 307Google Scholar.

24. Cited in Cantril, , Public Opinion, p. 574Google Scholar.

25. Cited in ibid., p. 199. Comparable polls of the later 1940s and 1950s indicate only slightly less Liberal strength among members of the “upper class” and “upper middle class” and confirm that the Liberals were the least class-bound of British political parties. See Rose, Richard (ed.), Studies in British Politics (London, 1966), p. 123CrossRefGoogle Scholar and McKenzie, Robert, “Between Two Elections”, Encounter, XXVI (1966), 14Google Scholar. As late as 1959, Sir Ivor Jennings detected “a general air of suburbia, small towns and seaside resorts about the constituencies in which the Liberal candidates did best.” Party Politics, I. 287Google Scholar. It was in precisely such areas that the Liberal revival in local government took place between 1959 and 1962. See Pease, Richard H., “The Liberal Vote,” Political Quarterly, XXXIII, No. 1 (July-Sept., 1962), 247Google Scholar.

26. Cited in Cantril, , Public Opinion, p. 198Google Scholar.