In the early seventeenth century, the parishioners of Bayton had a problem with alehouses. Only forty to fifty households lived in this Worcestershire village, but disputes over local drinking establishments sparked a series of complaints and counter-complaints between 1610 and 1621 that illuminate a broader issue in the history of popular politics in early modern England: the growing importance of local petitioning.Footnote 1 In 1610, some of Bayton's parishioners complained to the county magistrates that an ale-seller called Thomas Morely allowed “abuses and disorders” in his establishment and they asked for his alehouse to be “putt downe.”Footnote 2 Soon after, twenty men of the parish signed and submitted a counterpetition claiming that Morely was “honeste and cyville,” poor but hardworking, and without his alehouse there would be nowhere in the locality for travelers to stay or for workmen to be supplied with provisions. Two years later, a group of parishioners petitioned about this again, now targeting Elizabeth, Thomas's wife, who allegedly sold “extraordinary” powerful beer very cheaply, causing all sorts of “disorders,” including idleness, drunkenness, violence, and theft. Around the same time, nineteen named parishioners submitted a similar petition against John Kempster and Thomas Bird, also claiming disorder caused by their ale-selling. Then in 1613 the churchwardens of the parish petitioned the magistrates, now complaining about Thomas and Elizabeth Morely as well as Kempster and Bird, for continuing to sell beer and causing “abuses,” despite a warrant issued to suppress them. Finally, in 1621, eleven men signed their names to another petition accusing William Bryan and our old friend Thomas Morely of running alehouses full of “vagraunt,” lewd, and disorderly people.Footnote 3 In all, there were at least six different petitions and counterpetitions organized in little more than a decade, signed by dozens of individuals in a single village.

What does this flurry of complaints tell us about popular politics? It was an example of the rise of a broader culture of parochial petitioning, through which increasing numbers of ordinary people sought to win the support of state authorities through collective claims to represent the voice of the community at the local level. This article traces the intensification of these participatory and subscriptional practices in later Tudor and early Stuart England, through which petitioning became an essential component in the wider changes in local governance and political culture in these decades. Although there were few places quite as enthusiastic as Bayton in the early seventeenth century, the number of parishes where groups of locals banded together to petition the county magistrates was substantial and growing well before the mass petitioning campaigns that began with the summoning of the Long Parliament in September 1640. These parochial requests and complaints concerned a huge range of issues, but groups of parishioners frequently focused on “fiscal” issues such as eligibility for poor relief, liability for taxation, or responsibility for raising funds to maintain roads and bridges. Collective petitions about alehouses—whether complaining about alehouse keepers or supporting their requests for licenses—were common too, showing the importance of new regulatory responsibilities imposed by Tudor statutes on local communities.

This article examines the rising wave of petitioning from the late sixteenth century to the outbreak of civil war in England in 1642 and, more briefly, beyond, focusing on how the petitioners organized, represented, and justified themselves. Much existing scholarship has discussed petitions in this period, but it has tended to either focus on their role in national political campaigns or simply use them as evidence for examining specific local socio-economic issues. For example, many historians have almost exclusively foregrounded petitions to Parliament and to the king, especially the mass subscription campaigns that began in 1640 and the printing of many of these texts that began soon after. For some of them, the “origins of democratic culture” and “the public sphere” can be found in the combative published petitions that appeared in large numbers in this decade.Footnote 4 In contrast, other historians have examined petitions submitted to local authorities but have done so primarily as a way of investigating specific social problems, such as poverty, military pensions, alehouses, or cottage building.Footnote 5 However, the work of Keith Wrightson, John Walter, and others on “the politics of the parish” suggest the possibility of a “political” history of local petitioning.Footnote 6 Indeed, Wrightson himself drew attention to contentious petitions about alehouses and, more recently, Mark Hailwood and Heather Falvey have shown that these could be decidedly “political” documents.Footnote 7 Andy Wood and Amy Burnett have also suggested that subscribing to local petitions was an important component in the dynamics of “social exchange” and “neighbourliness.”Footnote 8

By looking at the full range of local petitioning practices, their relevance to the intensification of popular politics in the seventeenth century becomes clearer. They were not merely another example of an increasingly assertive “middling sort” dominating parish life. Instead, they were part of a broader set of socio-political developments that included changes in governance, communication, and representation. Local officeholding, citizenship, oath-taking, litigation, libeling, rumor, and riot have been highlighted by historians as contributing to a new way of thinking about politics among those outside the aristocratic elite.Footnote 9 Petitioning, this article suggests, was no less important.

To analyze these patterns with any degree of confidence requires a substantial dataset of petitions with granular information about topics, self-descriptions, subscribers, and other features. The basis of this article is therefore just over 3,800 manuscript petitions submitted to magistrates across fifteen jurisdictions with “sessions of the peace” in England, from the City of Westminster and several counties around London to Devon in the west and Cumberland in the north.Footnote 10 The sample includes petitions from the 1560s to the 1790s, though the vast majority come from the seventeenth century, with nearly 1,000 dating from before 1640. Together this corpus provides a wealth of evidence about their prevalence, aims, organization, and justifications.

Over the course of the early seventeenth century many, if not most, English parishes witnessed attempts to persuade the authorities through collective petitioning. Groups of neighbors across the kingdom formulated their grievances, organized subscription lists, and articulated their own role in the polity as “the inhabitants” or “the parishioners” of a particular community. In so doing, they not only directly shaped their own “little commonwealths” but also unintentionally helped to develop habits of political mobilization in a crucial period of English history.

The Popularization of Local Petitioning

The written petition was already a familiar tool for some people. Gentlemen, merchants, civic leaders, clergymen, officeholders, royal servants, and Crown tenants frequently submitted requests and complaints to the central authorities through a variety of routes. Royal councilors such as the Secretary of State and the Master of Requests as well as the monarchs themselves received vast numbers of petitions, with the majority coming from men with lands, titles, offices, or mercantile wealth.Footnote 11 Meanwhile, the Court of Chancery and other equity courts based at Westminster handled many hundreds of petitionary “bills of complaint” each year from lawyers on behalf of their clients, with men from the ranks of the aristocracy, gentry, and clergy markedly over-represented.Footnote 12 The process was arduous and expensive and this made participation impossible for many.Footnote 13 Although some less wealthy men and women did find ways to petition the Crown or the central courts, they were often outnumbered by their social superiors. Under the Tudors, it was only in exceptional moments that large groups of commoners came together to voice their complaints about public affairs through written supplications or “articles,” and they were met with sometimes lethal hostility from the authorities.Footnote 14

Petitioning local magistrates, in contrast, was less costly, less risky, and increasingly popular in Elizabethan and early Stuart England. It emerged from long-standing practices of addressing supplications or “plaints” to urban authorities or itinerate royal judges.Footnote 15 By the sixteenth century, people brought problems that could not be solved by manorial or parochial institutions to justices of the peace who assembled at regular quarter sessions and undoubtedly heard many orally presented complaints from an earlier date.Footnote 16 However, it was only under Elizabeth that significant numbers of people began to organize collectively to submit written petitions to the county magistrates. The first surviving complaints came from groups of parishioners in Essex in the late 1560s, and by the end of the century this practice was widespread.Footnote 17 Moreover, the trend continued under the early Stuarts. For example, the quarter sessions for Somerset, Staffordshire, and Cheshire together received well over 4,000 petitions over the course of these decades.Footnote 18 The magistrates of Lancashire dealt with more than 130 petitions in 1638 alone.Footnote 19 Although archival gaps make any estimate of national totals for this period tenuous, the sheer growth in numbers is unmistakable. As a result, ordinary people's familiarity with the form and procedure of petitioning reached unprecedented levels well before the mass campaigns launched during the Long Parliament.

Furthermore, virtually all petitions involved more than one person in their creation, namely a petitioner and a scribe, while many explicitly recorded the participation of more individuals as additional petitioners or supporters. The particular forms this took are analyzed in subsequent sections of this article, but surveying the sample of surviving petitions does allow some approximate quantification (Table 1). About a quarter of all local petitions (24 percent) came from collective groups such as “the parishioners” of a particular village, sometimes with substantial lists of subscribers. The remainder came from named petitioners, whether single individuals, couples, or small groups. These included some from groups of three or more named petitioners (5 percent) and some from only one or two petitioners but supported by at least three subscribers (6 percent). For example, the gardener Richard Jackson submitted a request to the Essex magistrates for a license to build a cottage in 1589, and his plea was backed by the subscriptions of fourteen fellow parishioners in Gosfield, including the minister.Footnote 20 Together, these various forms of collective and group petitions comprised more than a third (35 percent) of all the requests received by quarter sessions. As will be seen, nearly all of these petitioners were commoners rather than gentry or clergy, and they included a wide range of individuals, from poor widows and prisoners to prosperous yeoman and craftsmen. Given the number of women and propertyless men who actively took part in local petitioning, it was a far less socially exclusive practice than parliamentary voting or even parochial officeholding.Footnote 21

Table 1. Sampled petitions to quarter sessions, 1569–1639

Men and women pursued this tactic for a multitude of reasons, but they often revolved around recent innovations in public welfare and taxation or the regulation of rural housing and retailing. Indeed, many of these petitions focused directly on the implementation of new laws passed since the mid-sixteenth century. The majority came from people claiming or disputing specific statutory entitlements or responsibilities: parish poor relief (18 percent), local rates and taxes (9 percent), support for illegitimate children (9 percent), pensions for military service (2 percent), licenses to build cottages (11 percent), and licenses to keep alehouses (5 percent).Footnote 22 In the petitions submitted by groups of people or supported by multiple subscribers, these topics were even more prevalent, with almost two-thirds focused on welfare (24 percent), rates (16 percent), and licensing (25 percent). These requests were organized in response to the legal framework recently created by acts such as those mandating alehouse licensing (1551), cottage licensing (1589), relief for soldiers (1593), and of course the various poor laws (1552, 1563, 1598, 1601). The intensification of governance through new statutes and royal initiatives such as the “Books of Orders” meant that more people than ever had a reason to submit a petition to one of these sessions.Footnote 23 Moreover, many of these claims were successful, with the justices granting a substantial proportion of petitioners’ requests.Footnote 24 This created a mutually reinforcing cycle whereby every new petition, especially if followed by news of its success, made it more likely that someone else would attempt the same strategy.

Overlapping with these new statutory incentives and magisterial accessibility was “the fastest and largest growth in levels of litigation in recorded history.”Footnote 25 The swelling number of interpersonal suits in almost every court in Elizabethan and early Stuart England unsurprisingly provoked many of the petitions to county magistrates. Although most of these came from single individuals, a fifth of the total submitted by groups also focused on this topic. Many people banded together to use petitions to complain about vexatious prosecution or to request clemency. Others asked for their adversaries to be legally “bound to keep the peace” or otherwise punished.Footnote 26 In 1599, for example, nine parishioners of Kings Norton successfully sought an order from the Worcestershire sessions against a neighbor who had caused “the greevous abuse and disturbance of a great part of hir majesties subjectes there inhabytinge,” while in the same year nineteen men of Droitwich asked these justices to release the widow Margaret Jefferies from her bond “for her good behavioure” because “the controversies” between Jefferies and her son were now resolved.Footnote 27 The broader growth in litigation thus provoked petitions directly and led many litigants to seek out allies who might be willing to subscribe to their requests. It also drove the growth in the number of provincial scribes, scriveners, and legal advisors who helped to craft these documents, providing a ready source of expertise for potential petitioners.Footnote 28

This period also witnessed several surges in petitioning at the national level that must have had an influence on local practice at this time. Many craftsmen and tradesmen in London gained an intimate familiarity with assertive forms of petitioning though the intense lobbying campaigns of the Livery Companies, and groups of traders outside the capital also joined the fray in the 1620s when Parliament showed itself very willing to hear grievances about monopolies and patents issued by the Crown.Footnote 29 Likewise, the multitudes of collective supplications organized by provincial puritans seeking doctrinal and ecclesiastical reforms helped to develop the petitionary proficiency of numerous clerical and lay activists. Although the so-called “Millenary Petition” submitted to James I at his accession did not actually include the thousand subscribers implied in its title, it was just one of many organized from the 1580s onwards that together involved many hundreds of reformers.Footnote 30 The most famous petition of this period, the so-called Petition of Right from Parliament to the King in 1628, did not involve any participation from the sorts of people who submitted requests to their local magistrates.Footnote 31 It was, however, officially printed and disseminated, then discussed by many outside Parliament who had an interest in politics.Footnote 32 Moreover, its appearance in various publications was merely one example of a broader development whereby “a diverse range of printed and manuscript petitions and supplications that adopted the voice of the people” were produced in growing numbers in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 33 It would, therefore, be unsurprising if the carefully crafted complaints to the county justices were occasionally shaped by local knowledge of particular national petitions. Yet it is equally likely that these innumerable mundane requests helped to develop a culture of petitioning in towns and villages that some activists then used when attempting to coordinate campaigns directed at the king or Parliament.

The popularization of local petitioning in these years meant that the practice of organizing a written appeal to authority was no longer pursued predominantly by a narrow group of gentlemen, merchants, and professionals. The quarter sessions records held in many different archives show that it was an increasingly widespread activity and included many people who had no legitimate role in conventional politics. In the early decades of Elizabeth's reign, the number of individuals with direct experience of coordinating or contributing to a petition was negligible, whereas in the early seventeenth century tens of thousands of men and women created or subscribed to petitions about a huge range of practical administrative and judicial matters that they submitted to the local magistrates.

Collective Representation and Organization

No rules governed how petitioners should identify themselves in their requests and, as a result, they appeared in a great variety of forms. During the struggle over alehouses in Bayton, discussed above, one petition came from “the parishioners and the inhabitauntes,” another from “us the parishoners of Bayton,” and another simply from “wee whose names are underwritten.”Footnote 34 Looking across hundreds of other local petitions from this period, one finds many different modes of self-presentation, often showing evidence of preparatory organizing and tactical thinking. While their aims were local and practical, some hint at the sort of strategies that became much more visible in the politicized petitioning campaigns of the 1640s.

Such issues were not especially relevant in many cases, because most petitions came from just one petitioner and most of these were not signed. Later there were attempts to ensure that petitioners signed their texts, but there is no evidence that this was required—or even expected—before the Civil Wars.Footnote 35 Instead, the identity of the petitioner was usually simply expressed in the title or the first line of text, as in “The humble peticion of Richard Beamond late of Weever laborer” or “Your lordships humble petitioner Anne Barlowe.”Footnote 36 These texts included the individual's name and residence, occasionally alongside their occupation or marital status. Here, any self-description was usually focused on personal helplessness and deservingness: “a poore distressed man,” “a poor ympotent and blind widow,” “a poore maimed Souldier,” “a poore chreature.”Footnote 37 These petitioners presented themselves as individuals or, at most, householders, rather than claiming to speak for a broader community.Footnote 38 This was still an expression of a certain kind of politics, namely the traditional paternalism that Tudor and early Stuart monarchs sought to encourage and reinforce, but it initially appears very different from the sort of popular politics that tends to be associated with collective petitioning.

However, even requests from single individuals almost always involved collaboration and negotiation. The most consistent element of this was the involvement of a scribe. The number of individuals who wrote their petitions in their own hands was vanishingly small, though the nature of these documents means that it is not possible to estimate this with any precision. Based on an evaluation of idiosyncrasies in script, spelling, and expression, fewer than one in fifty local petitions were autograph manuscripts, written by the named petitioner themselves.Footnote 39 This was partly due to widespread illiteracy, but the most important factor was that petitioners understood that these texts were expected to be presented in a particular format so they logically turned to people with more expertise to pen their texts. Virtually no local petitions explicitly mention their scribe, but fragmentary evidence suggests that they might have been written by a professional, whether in the petitioner's own neighborhood or in the county town where the quarter sessions were meeting, or they could be composed by a sympathetic supporter with some degree of knowledge of the form, such as a parish clergyman.Footnote 40 Alongside this scribal service, the process of composition often must have involved receiving advice about the law and the expectations of the magistrates. This could have been provided by the person writing the petition if, for example, they were a trained scrivener, but additionally could involve guidance from petty legal practitioners—the multiplying country attorneys studied by Christopher Brooks—and others with a smattering of legal knowledge, including neighbors, employers, or landlords.Footnote 41 Finally, as explained below, even individual petitions might include supporting subscribers. Therefore, while petitions may occasionally have been submitted to the justices by a single supplicant with little or no involvement from others in their communities, most of these manuscripts integrated contributions from multiple people, ensuring that knowledge of the process gradually spread through the wider population.

The collaborative—even collective—nature of seemingly “individual” requests is obvious in some of these texts. “The humble peticion of Cassander [sic] Godwin the wife of James Godwin,” for example, was submitted to the Westminster magistrates in 1627 after she was “bound over” by one “Mistress Lucie” for allegedly striking Lucie's child. Unsurprisingly, Godwin claimed her innocence and asked to be discharged, but more tellingly an additional supporting text was pinned to the main petition from twelve “subscribed parishoners … att the request and desiere of the bearer hereof our neighbour,” where they supported her version of the narrative and noted that she “lived in a good and quiet sort.” These twelve subscribers included nine men, who all signed their names, and three women, two of whom used marks rather than signatures. This began, then, as a very personal and traditional request for mercy, but Godwin's canvassing of the neighborhood for subscribers turned it into a well-attested statement of local opinion.Footnote 42 Such individual petitions backed by named supporters overlapped with petitions from groups “on behalf” of specific individuals. Indeed, many petitions that were submitted on behalf of a single person were explicitly collective in nature. For instance, a coalition of “neigbors” in East Grinstead, Sussex, sought an alehouse license for a local widow, Alice Undrith, in 1598. They described themselves as “we your poore neighbors, Inhabitants of the said burrough whose names are here underwritten,” who were “moved with pitie But also Requested of Charite” to write “on the behalf of our poore neighbor.” It was subscribed by twenty men, including two constables and a bailey, and clearly organized by Undrith, who had “Requested” their action, despite the fact that she did not sign it.Footnote 43 Both Godwin and Undrith evidently believed that it was worth rounding up supporters within their communities instead of simply submitting a single plaintive request, meaning that the line between “individual” and “group” petitioning was often blurred. The former might involve just as much negotiation and cooperation among neighbors as the latter.

Some individuals explicitly claimed to represent a whole group or community, relying more on their office or position than on a list of named supporters. In their petitions, they became delegates who might legitimately speak to authority on behalf of their neighbors. One of the complaints about disorderly alehouses at Bayton fits this model perfectly: it came from “us the parishoners of Bayton” according to the main text, but was only signed by John Geers and Edward Sutton, the village's two churchwardens.Footnote 44 This exemplified a common approach wherein the only named petitioners were parish officeholders, acting in the name of the wider community. In many cases, the churchwardens, the overseers of the poor, or the surveyors of the highways identify themselves as individual officers while explicitly seeking communal redress, such as “to free the said parish” from relieving a poor soldier's wife or forcing negligent landholders to maintain local highways that “have byn much decayed.”Footnote 45 Even more direct was a request submitted to the Staffordshire magistrates in 1609 for a maintenance order against the reputed father of a poor “basterd chyld.” It began by announcing that it was from the “overseers of the poore within the parishe of Gnossall, in the behalffe of the whole parishe,” thereby establishing the four named petitioners as supposedly authentic representatives of their entire community.Footnote 46

A formal office was not always necessary for this type of claim. Occasionally the mode of address implied a process of delegation operating outside the established judicial and political hierarchy. One request from Cheshire in 1608 for the repair of three bridges using county funds was from “John Mynshull of Mynshull and Thomas Mynshull of Erdeswicke Esquires together with the rest of the parishioners of Church Mynshull and Midlewyche parishe and the inhabitants of the Towneshipes of Church Myshull, Weever and Wymboldesley and Mynshull Vernon.” The two named men were established gentry landlords, yet their official role was not stated and their voices were rhetorically combined with “the rest of the parishioners” and with “the inhabitants” of four distinct settlements, a point reinforced by a closing prayer from “we the neighbours of the foresaid place” and a set of six subscriptions that included not only the two esquires but also four other men who may each have spoken for one of the townships.Footnote 47 The petition was thus simultaneously from two gentlemen, four additional representatives, and the whole neighborhood.

The collective voice of a community did not necessarily need to be ventriloquized by named representatives in local petitions and many organizers adopted a more direct approach. In these texts, the petitioners usually simply identified themselves as “the parishioners,” “the inhabitants,” or a similarly undifferentiated group, sometimes supported by a list of signatures but equally often unsubscribed.Footnote 48 Such requests are among the first surviving quarter sessions petitions in England, with two dating from 1569 preserved in the Essex sessions papers. One came from “We the parisshioners of Stamborne” against a neighbor for taking in poor lodgers and the other from “the Towneshyp of Blackmore” for reimbursement after some grain was seized for royal use. These early examples were entirely typical of a collective mode of representation that was widespread in this period, wherein the complainants asserted a strongly corporate identity. Although this idea is usually associated with the increasing number of so-called “city commonwealths” issued with royal charters in this period, it was also very evident in many requests submitted to local magistrates from rural parishes and unincorporated small towns.Footnote 49

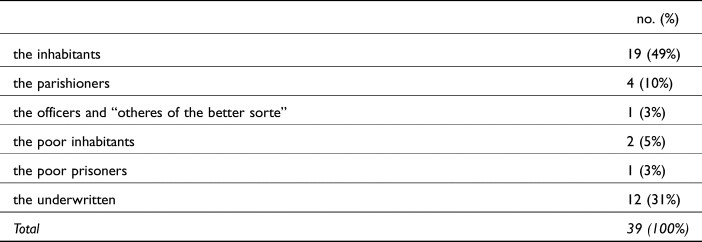

A more detailed examination of the thirty-nine extant collective petitions submitted to the justices of the peace for Hertfordshire from the 1590s to the 1630s highlights the most frequent self-descriptions (Table 2). Twenty-three of the petitions simply came from “the inhabitants” or “the parishioners” of a named settlement, implying a unified, inclusive, and nominally equal community.Footnote 50 In a few cases, they were more specific. For example, two were submitted by “the poor inhabytantes” of a locality, one from Cheshunt complaining about profiteering grain dealers during the dearth of 1595 and the other from Aston seeking redress against a master who refused to pay his elderly servant her overdue wages in 1597.Footnote 51 In both these cases, the self-description used by the petitioners suggested a communal complaint while foregrounding their apparent weakness and vulnerability to unscrupulous neighbors.Footnote 52 Only one group of petitioners in the Hertfordshire subsample introduced themselves to the county's magistrates using a more socially exclusive phrasing. In 1602, “the Churchwardens, Overseeres and Constables and otheres of the better sorte of the parish of Widforde” complained about the recalcitrance of an illegitimate poor child's putative father.Footnote 53 This is one of the very few extant examples of collective petitioners explicitly labeling themselves as an exclusive and superior group within the wider body of the locality. Despite many suggestions in the historiography that England's parochial elite increasingly saw themselves as a morally and politically separate minority in this period, there is little evidence of self-described “better,” “principal,” or “chief” inhabitants in Elizabethan or early Stuart petitioning.Footnote 54 As Henry French has noted in his work on “the middling sort” in quarter sessions records, such explicit status divisions were nearly always elided among those writing to the county authorities at this time.Footnote 55 Instead, it was the voice of the parish as a whole that supposedly spoke in most of these petitions.

Table 2. Self-description in collective petitions to Hertfordshire quarter sessions, 1590–1639

However, it was not merely parishes or townships that presented themselves as united corporate bodies in such texts. For example, among the Hertfordshire set, one petition was submitted by “we the fortie poore prisoners” at Hertford Gaol in 1602.Footnote 56 They were seeking judicial mercy while, through the label they chose for themselves, expressing both their shared identity and their disadvantaged position. Groups of prisoners in other counties did likewise, such as “the poore prisoners of the castle of Worcester” in 1619, “the prisoners beinge debtours in the Gatehouse” of Westminster in 1625, and “the poore & distressed prysoners nowe remayning within the Castle of Chester” in 1628.Footnote 57 Richard Bell has shown that inmates in the larger London prisons at this time were highly organized and very willing to collectively complain about their conditions, and it seems their provincial counterparts pursued similar petitionary strategies.Footnote 58 Meanwhile, occupational groups—whether formal organizations or merely informal coalitions—also submitted petitions to the local magistrates that expressed a shared corporate identity. In 1635, the “loud musique called the waytes appointed for the city and liberties of Westminster” petitioned the justices to protect their civic monopoly against an intruding musician.Footnote 59 However, occupational petitions did not always come from official guilds and associations in the corporate towns. A more informal group was “the Weavers of Braintree & Bocking” who submitted a plaintive request for “redress” due to depressed trade in 1629.Footnote 60 Despite lacking formal status as a “corporation” or “company,” these Essex tradesmen—like the Hertford prisoners—forcefully articulated a collective identity through their petition.

Perhaps the most impressive example of this type was the complaint from a group of fishermen describing themselves as “your Petitioners being many hundreds in number of the Counties of Worcester and Salop” addressed to the Worcestershire magistrates in 1613.Footnote 61 These men presented themselves as not only extraordinarily numerous and geographically widespread, but also as established householders “having wives and families to maintaine” and as skilled workers having “served their apprentishipps to the trade of fishing.” According to their petition, unlicensed “countrymen” were exhausting the River Severn with “forestalling netts,” thus ruining the livelihoods of the “many hundreds” in both counties who relied on its natural bounty. Only a “generall order” from the bench, they argued, could restrain these miscreants who “offend and persist against the good of the kingdome.” Through this assertive rhetoric, the fishermen contended that they were a broad and important constituency that should not be ignored. No subscription list has survived to prove the specific suggestion that they numbered “many hundreds,” but the language of the petition nonetheless implied something closer to a popular campaign for government action against a common threat than a narrow complaint about a few disorderly individuals.

Such claims to represent a wide but coherent community infused the texts of other local appeals and requests. Even petitioners who did not describe themselves in these terms might seek to present their case as a communal concern with major public implications. Occasionally, for instance, small groups of inhabitants suggested that the misbehavior of their adversaries was disturbing “a great part” of the parish's population, that it was intolerable “in soe well governed a common wealth as this is,” or that it offended against the whole “Christyan comon wealth.”Footnote 62 While such explicit rhetorical invocations of the public good were rare in these texts, they were symptomatic of a general tendency among local petitioners to justify themselves through reference to the impersonal requirements of “law,” “statute,” “equity,” or “justice.”Footnote 63 Supplicatory pleas for the mercy or charity of county magistrates were also frequent, yet potentially more contentious ways of thinking about the responsibilities of state authorities were already very evident among the men and women who organized appeals to the quarter sessions at this time.

An extraordinary petition submitted to the justices of the peace for Lancashire in 1606 exemplifies the potential ambition of some claims to speak for the public interest. Although no specific individual or group were named as petitioners, the complaint outlined how “the countrie [was] oppressed” by servants demanding high wages and “seeking libbertie to worke when thay please,” and how “housekeepers” (householders) were threatened by thieving “masterlese people.” It asked for the magistrates to establish a House of Correction and an annual meeting to set wages “according to lawe,” because husbandry and “all trades” in the county were failing “through want of execucion of such like goverment, as is in the south parte of this Realme.” If the justices acted quickly to redress this social and economic “decay,” then “thee Contrie” would of course be grateful, but the collective danger of inaction was also made clear.Footnote 64 In this case, the petitioners presented themselves as very directly vocalizing the concerns of “the countrie” and its householders, seeking statutory justice and good “goverment.”

There was, therefore, a wide spectrum of ways that petitioners described themselves and their concerns, from narrow and particular to broad and general. The latter are most visible in the many collective complaints that reached the county magistrates, yet more ambitious claims can also sometimes be glimpsed in the ways that individuals or very small groups organized and composed their appeals. As local petitioning became increasingly ubiquitous under the early Stuart kings, more and more people began to engage in the politics of representation through this medium.

Subscriptional Practices

From a modern perspective, a list of signatories is integral to the nature of a petition. In medieval and indeed in many early modern contexts, this particular feature was both unnecessary and rare. Most petitions to county quarter sessions did not include any subscriptions, and this is a useful reminder that petitioners could engage in popular politics without attempting to gather names. Yet, signatures and marks appear often enough to be worth closer examination. After all, most of the petitions about Bayton's alehouses, discussed above, were subscribed by a group of named individuals. Three of the documents together include thirty-six individual men's names, with fourteen of these appearing on more than one petition. Another had a subscription list, which unfortunately has not survived, and a fifth document—now lost—may have included still more names. As the parish had only thirty taxpaying men in 1524 and perhaps forty-five to fifty families by 1676, it seems clear that most of Bayton's householders signed their names to one or more of these petitions.Footnote 65

One type of request fits the subscriptional model better than any other because it was presented first and foremost as the voice of a group of identifiable individuals rather than as a statement from a whole parish or similar body. Instead of using an anonymous title such as “the inhabitants” or “the parishioners,” these petitioners began their appeals by describing themselves as “we whose names are hereunto subscribed,” “wee whose names bee heerunder written,” or some very similar formulation.Footnote 66 Such phrasing appears at the start of about a third of the collective petitions in the Hertfordshire subsample (Table 2), so it was not merely a rare deviation from the norm. In these documents we can perhaps see a belief among at least some people that a temporary, informal coalition of individuals had as much right to petition the magistracy as a more formally constituted body. Although they almost always specified that they were residents of a specific place, they made no claim to represent the whole village or neighborhood as a single entity. For these petitioners, their own individual identity remained visible and important, even as their particular concerns were amalgamated into an unmistakably collective voice.

In practice, however, the distinction between primarily subscriptional appeals from “the underwritten” and petitions from corporate entities, named officers, or even single individuals was blurred by the tendency of the latter types to occasionally include significant numbers of subscriptions and the former type to regularly include only a few. Across the whole sample of 969 local petitions submitted before 1640, a total of 21 percent had three or more subscribers, including small proportions of the many petitions from individuals or couples (Table 1). As already discussed in the cases of Cassander Godwin and Richard Jackson, women and men making “personal” appeals for relief or mercy might recruit neighbors to endorse their claims with signatures or marks.Footnote 67 Likewise, requests presented by churchwardens, constables, or overseers could be reinforced by the addition of subscriptions from the wider community, effectively authenticating the representative status of these parish officers.Footnote 68 Meanwhile, among those that presented themselves as “the parishioners,” “the inhabitants,” or a similar collective group, a majority (56 percent) had multiple subscribers, but this was obviously not a requirement, or even a standard expectation, because the rest had only one or two, or even no subscribers at all. We should not, therefore, attempt to draw a firm line between “traditional” corporate or personal petitioning and “modern” subscription-based petitioning.

A closer examination of the 205 petitions with three or more subscribers reveals that they had an average of twelve names attached to each, but this overall figure hid great variation. There was, perhaps surprisingly, no obvious pattern in the number of subscribers. Rather than most petitions having ten, twelve, or twenty supporting names, one finds a reasonably even spread from three to fourteen subscribers, with larger numbers featuring more rarely (Figure 1). These were not, therefore, simply lists of the members of the self-selecting councils or “close vestries” that were emerging in many localities at this time.Footnote 69 Most had ten or fewer subscribers, but almost as many had more than that, and one in eight (12 percent) had twenty or more. These larger groups were diverse in terms of their aims and survive from almost all sampled counties. For example, thirty subscribers supported an anti-alehouse petition in Hertfordshire in 1598, but forty-one individuals included their names on a pro-alehouse petition in Somerset in 1627.Footnote 70 More numerous still were the seventy parishioners of Weston near Bath who together requested a cottage license for their neighbor, Thomas Warde, a wheeler, in 1617.Footnote 71 The largest group of all was the nearly one hundred inhabitants of four different townships in Cheshire whose names were added to a request to dismiss allegations against John Yate of Middlewich, an “honest and civill” young man, in 1608.Footnote 72 Most rural settlements had only twenty to forty households at this time, so these well-subscribed petitions made a forceful representational claim merely through their numerical scale.Footnote 73

Figure 1. Subscribers per petition in sample (n = 205), 1569–1639

No matter how numerous they were, subscribers did not represent a genuine cross-section of the whole population of a particular community, especially in terms of gender. Men were strongly prioritized by anyone gathering subscriptions, whereas women were almost invisible in this part of the petitioning process, though there was evidently no formal rule against their participation. Approximately 95 percent of all subscribers’ forenames were identifiably male and a further 4 percent were unclear or unknown.Footnote 74 Only about one in a hundred had female forenames, a vastly smaller proportion than the quarter of petitioners who did.Footnote 75 Their occasional appearance does, however, show that some women were seen as sufficiently “credible” to be a valuable addition to a list of subscribers. In 1620, for example, when nine “neighbours and tenants” of Fladbury petitioned the magistrates of Worcestershire seeking a cottage license for Katherine Emmes, the mix of signatures and marks at the bottom of the page included “Marget X Farrie hur marke” alongside the names of eight men.Footnote 76 Likewise, in 1628, Anne Greene joined with seven men of Wybunbury—including the parish constable—in requesting action against a neighbor who they accused of a long list of disorderly and immoral behaviors.Footnote 77 Intriguingly, Greene was one of the three subscribers who signed their names in full while the rest of the men used only marks. These women were, however, very rare exceptions to the typical practice of including only male subscribers on petitions to the quarter sessions.

The men whose names filled the list at the bottom of many requests occasionally attempted to enhance their standing by adding titles, though this practice was far from universal. Just under half of the petitions with groups of subscribers that were submitted to the Hertfordshire magistrates before 1640 included any such status labels. Among the 412 subscribers to these requests, twenty-three people (6 percent) added additional information apart from their names. These were eleven clergymen (“vicar,” “clerk,” “minister”), eleven parish officers (constables and churchwardens), and Katheryn Dyer, widow (“vid.”).Footnote 78 Notably, not a single “gent” or “esq” appeared in these lists. The prominence of local ministers among subscribers is unsurprising because their presence offered a useful stamp of credibility, even authority, to otherwise undifferentiated coalitions of individuals. As these clergymen sometimes served as the petitioners’ scribes, specifying their position may have also helped to authenticate the text and the other subscribers. In similar ways, just as it was relatively common for parochial officers to submit petitions on behalf of whole parishes or individual neighbors, it seems that the status that came with local officeholding might also be considered helpful when assembling supporters. Nonetheless, the number of subscribers who explicitly labelled themselves as constables, overseers, or churchwardens was relatively small. In fact, they were probably under- rather than over-represented, because approximately one in twenty adult men held a local office each year, whereas only one in forty subscribers in the subsample laid claim to this status.Footnote 79 Overall, these collections of names were remarkably unadorned. While titles and offices were powerful tools in the so-called “politics of the parish,” they evidently mattered relatively little to the politics of local subscription.

The nature of the subscriptions is also revealing. The vast majority of names were written out in full (94.5 percent), with only a small proportion leaving marks (4.9 percent) and a negligible number of initials (0.6 percent).Footnote 80 At first glance, this might appear to show spectacularly high levels of literacy among subscribers to local petitions, because in other sources from this period most people left marks or initials.Footnote 81 However, the remaining names are a mix of autograph signatures and scribal subscriptions, with multiple names written by the same hand. It is not always possible to distinguish consistently between these two methods of signaling the support of individuals, but at least a fifth of the total—and perhaps significantly more—were scribal subscriptions rather than unique signatures. In 1594, for example, “the Inhabitantes” of King's Langley in Hertfordshire submitted a petition requesting a cottage license for Edward Simson, “an honest poore man destitute of a dwelling house.” At the head of the list of subscribers, the scribe wrote “per me Richard Adames, pastore de Langley”; his distinctive hand had also penned the main text as well as the names of the other eight supporters.Footnote 82 Although three of the men added their own unique marks next to their names, the rest did not, so it seems that neither these “humble Supplicantes” nor the magistrates believed that petitioners needed to authenticate their support with a signature or mark.

Often a single petition included more than one type of subscription. In 1619, for example, Roger Boulton and William Clowes of Hanford asked the Staffordshire magistrates to release them from their recognizances and take action against John Johnson, who they accused of malicious prosecution and fathering a bastard with “a notorious strumpet” that might soon become “chargeable to the parishe.” Yet they were not acting alone, for the petition was also subscribed by the parish minister and more than forty other men.Footnote 83 Notably, the whole manuscript is a mix of different hands: the text of the petition itself is in one hand; the subscriptions of the petitioners, the minister, and four other men is in another; six other hands wrote the names of forty additional subscribers; and four names appear to be autograph signatures. It seems that eleven literate individuals penned the almost fifty subscriptions on this petition. This might, at first, suggest an attempt at deception, with a small cluster of men trying to present themselves as a much broader group. But given how often other local petitions include similar sets of subscriptions in the same hand, this is very doubtful. The more likely explanation is that autograph signatures—or even unique marks or initials—were not seen as especially important to the practice of petitioning at this time. Put simply, such manuscripts show that many petitioners believed that it would be beneficial to back their requests with a number of named supporters, yet they saw little difference between a subscriber who signed themselves and one who merely agreed to having their name added. One could, therefore, join a coalition of neighbors submitting a petition by helping to organize and compose it—even if it was submitted without any subscriptions—or by ensuring that one's name was added—even if a more literate neighbor actually wielded the pen—or of course by writing one's own signature.

Subscriptions in local petitioning were, therefore, common and meaningful but not essential nor consistently autographical. The fact that they were deployed regularly and that they occasionally resulted in long lists of named participants demonstrates that the practice of gathering subscriptions was becoming increasingly familiar to many ordinary people thanks to the expansion in local petitioning. We should not equate these neighborhood campaigns about poor relief, alehouses, or petty criminality with the mass petitions about church and state that followed. For example, the more than 3,000 subscriptions attached to Cheshire's many local petitions in the first four decades of the seventeenth century were qualitatively different in scale and aims from the 6,154 subscriptions reportedly collected in that county in a single petition to defend episcopy in early 1641.Footnote 84 Nonetheless, as more and more people took part in parochial organizing and canvassing, this practice became thoroughly embedded in popular political culture.

A Longer-Term Perspective

Petitioning was not an innovation of late Elizabethan England. Even the more specific act of submitting a written petition to a local magistrate can be glimpsed occasionally in earlier records. For instance, half a dozen supplications to the Norwich civic authorities survive from the 1530s, including a few from individuals seeking mayoral adjudication in conflicts with neighbors, one from two “Wardens” representing the “occupacion of rough masons” against an unlicensed craftsman, and one from thirteen named “makers of Tallow Candylls” for permission to produce wicks without cotton so that “All your Comons shalbe suffycyently servyd.”Footnote 85

Yet surveying the development of local petitioning across the early modern period shows that this practice spread much more widely in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Many thousands of people in villages and market towns initiated, organized, or subscribed to written complaints and appeals about a broad range of local issues. They petitioned—whether individually or collectively—about disorderly behavior, unjust imprisonment, alehouse licenses, cottage building, parish rates, poor relief, and much else. Moreover, local petitions might follow very traditional forms, but they also regularly reveal more “modern” ways of engaging with the authorities. Superficially “personal” requests from one or two named individuals almost always involved working collaboratively with a scribe, often drawing on a wider pool of expertise among their neighbors, and in many cases canvassing for supporting subscribers. The same practices underwrote delegatory petitions submitted by parochial officers, who frequently took pains to represent themselves as speaking on behalf of the whole parish, rather than merely on their own authority. Collective petitions took this further, insisting on a shared voice that implied a broad consensus among “the inhabitants” rather than trying to embody the “better” local elite.

Furthermore, the lists of names attached to so many requests submitted to county magistrates show that subscriptional practices of organization and negotiation, which would become central to popular politics in the 1640s, were already spreading through innumerable rural parishes across the kingdom. Their numbers were often impressively large considering the small pools from which they drew, and the frequent lack of distinctions among “the undersigned” suggests that status was not necessarily as important as is sometimes assumed. While all petitions were shaped by inequalities of gender, wealth, and officeholding, many nonetheless intentionally presented the impression of “a horizontal sort of beast,” demonstrating a form of political engagement that was remarkable in its social breadth and depth.Footnote 86

The vast expansion in local petitioning established a subscriptional habit that was transformed into a national partisan tool with the eruption of mass petitioning that followed Charles I's recall of Parliament in 1640. It began with the so-called “Root and Branch” petition for church reform reportedly subscribed by 15,000 Londoners that autumn, but this was just the first shot in a series of campaigns that involved tens of thousands of named petitioners from across the country in the 1640s and 1650s.Footnote 87 Further outbursts during, for example, the Exclusion Crisis of 1678 to 1681 meant that mass petitioning became a core part of popular political culture in England for many decades to come.Footnote 88 It is, therefore, remarkable that practices of local petitioning changed relatively little in most respects after 1640, apart from a new tendency for some petitioners to draw on tropes from national political rhetoric in their parochial struggles.

After growing steadily across the early Stuart period, the sheer number of local petitions seems to have risen further in the middle decades of the seventeenth century, before peaking and beginning to decline in most counties during the reign of Charles II.Footnote 89 Although petitions survive from many local jurisdictions in the eighteenth century, including nearly 10,000 submitted to London's overlapping judicial institutions, requests of this type appear to have been increasingly uncommon or were dealt with outside the formal sessions of the peace. Levels of litigation were declining, and some problems could be more easily handled by petty sessions or statutory authorities such as turnpike trusts.Footnote 90 Meanwhile, the proportion that came from collective groups or multiple named petitioners remained roughly the same during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, before declining somewhat in the later seventeenth century and continuing at that slightly lower level into the eighteenth century. Likewise, there was no sudden increase in subscriptions after 1640. The proportion that had three or more named subscribers was stable throughout the period, with perhaps a slight decline after 1660. Indeed, this stability in subscriptional practices seems to have continued into the eighteenth century too.Footnote 91

It is, therefore, unsurprising that more than four decades after the storm of complaints about alehouses in Bayton, another petition about the same subject from the same village was submitted to the Worcestershire justices in 1666. It came from twenty-three “inhabitants” who did “humbly importune” the magistrates to suspend the alehouse license recently granted to Daniel Roberts. Like many early Stuart requests, it was supported with a mix of autograph signatures and scribed subscriptions, including the vicar and two churchwardens. The only aspect of the petition that distinguished it from its predecessors was the justification used by the complainants: they argued that Roberts was unfit to sell ale because “in the late warres [he] tooke up armes against his majesty” and more recently had refused to attend the established church “to hear divine service and sermon at time appointed.”Footnote 92 While the heavy-handed references to religious and political nonconformity gave the petition's rhetoric a distinctly Restoration edge, it was very similar to earlier requests in terms of its organization and form.

So, if practices of local petitioning were characterized more by continuity than by change after 1640, then the rapid expansion of the practice in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries makes this the most important period for understanding its role in early modern popular politics. It was then that its key features solidified and spread, such as the participation of undistinguished “inhabitants”—including poor men and women—alongside claims to popular representativeness and the occasional use of numerous subscriptions. The term “vox populi” would have meant little to most of the petitioners mentioned in this study, but their efforts nonetheless indirectly contributed to the growing prominence of the voice of the people as a central part of English political culture.