Introduction

Skilled comprehenders construct a coherent mental representation of the state of affairs described in the discourse (Johnson-Laird, Reference Johnson-Laird1983; Van Dijk & Kintsch, Reference Van Dijk and Kintsch1983). The formation of a coherent mental representation (or situation model) is guided by the presence and understanding of referential expressions such as pronouns, which mark whether (new) information is coherent with the current representation in terms of maintaining or shifting the focused entity (Varma & Janssen, Reference Varma and Janssen2019; Zwaan & Radvansky, Reference Zwaan and Radvansky1998). It is well established that adults and children tend to interpret ambiguous personal subject pronouns (e.g., he, she) with the assumption that they refer back to the most accessible entity within their representation of the prior discourse (Gundel, Hedberg & Zacharski, Reference Gundel, Hedberg and Zacharski1993; Hartshorne, Nappa & Snedeker, Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015; Hughes & Allen, Reference Hughes and Allen2015). Specifically, the extent to which adults and children weigh the accessibility of an entity as the pronoun referent is determined by prominence cues, such as order of mention (first > second), grammatical role (subject > object), and semantic role (proto-agent > proto-patient) (see Ellert, Reference Ellert2011). In English, these cues typically converge onto the same entity, as in (1) where the firefighter is the first mention, subject, and agent.

(1) The firefighter wants to rescue the boy but he is way too nervous.

Multiple studies of adults have used flexible word order languages like German and Finnish to disentangle these cues, revealing that comprehenders follow a combination of these cues, and suggesting further that semantic role may play a decisive part (Järvikivi, van Gompel & Hyönä, Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel and Hyönä2017; Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä & Bertram, Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005; Schumacher, Backhais & Dangl, Reference Schumacher, Backhaus and Dangl2015; Schumacher, Dangl & Uzun, Reference Schumacher, Dangl, Uzun, Holler and Suckow2016; Schumacher, Roberts & Järvikivi, Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Whilst child language developmental studies have used flexible word order languages to tease apart the influence of order of mention, grammatical role, and semantic role within various sentence-level test-beds (e.g., Brandt, Kidd, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Brandt, Kidd, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Chan, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Chan, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Dittmar, Abbot-Smith, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Dittmar, Abbot-Smith, Lieven and Tomasello2008; Grünloh, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Grünloh, Lieven and Tomasello2011), these cues have not yet been fully disentangled in relation to ambiguous pronoun interpretation. In the present visual world eye tracking study, we investigated the influence of these cues on seven- to ten-year-olds’ comprehension of German sentences containing the personal pronoun er, and d-pronoun der. Our observations advance understanding for how children differentially weight cues to guide their interpretation of pronouns, and indicate a developmental increase in their use of semantic role.

Over three decades of literature on adult pronoun interpretation has provided theory and evidence that first mention and subjecthood features of prior discourse are both important factors within prominence-driven resolution of subjective personal pronouns (e.g., Crawley, Stevenson & Kleinman, Reference Crawley, Stevenson and Kleinman1990; Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Gernsbacher, Reference Gernsbacher1990; Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005; Keenan, Reference Keenan and Li1976). Subjecthood is assumed to have greater accessibility than objecthood because of a privileged status within grammatical operations where the subject is higher than the object (Diessel, Reference Diessel1999; Keenan, Reference Keenan and Li1976). Additionally, the first mentioned character of the prior discourse is theorized to gain privileged status as the foundation structure for which a mental representation is built (e.g., Gernsbacher, Reference Gernsbacher1990; Gernsbacher & Hargreaves, Reference Gernsbacher and Hargreaves1988). As noted, adult studies have made use of flexible word order languages to disentangle order of mention from grammatical role. In SVO order, the prominent order of mention (first) and grammatical role (subject) cues are aligned; whereas in OVS order, the prominent order of mention cue (first), is aligned with the low prominence grammatical role cues (object) – that is, the object argument of an active accusative verb is ordered first. In a visual world paradigm (VWP), Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017: Experiment 1) operationalized this by using German active accusative verbs such as umarmen “to hug”, küssen, “to kiss”, and schlagen “to hit”. Personal pronouns were more robustly attached to the subject than to first mention, and this subject preference was enhanced when it converged with first mention (SVO order). Such VWP findings have been observed across a variety of other languages including Dutch (Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2004), Finnish (Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005) and Russian (Krasavina & Chiarcos, Reference Krasavina and Chiarcos2007).

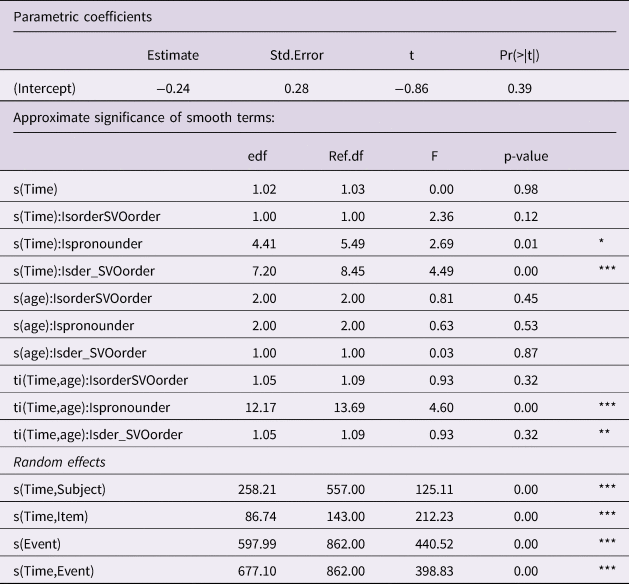

However, the previous findings of a subject preference have also been attributed to agentivity, as the design described above does not disentangle grammatical role from semantic role. In addition to the two structural prominence cues of subjecthood and first mention, a prominence hierarchy within semantics is proposed to influence pronoun resolution. The subject and object arguments of a verb can be ranked in terms of the degree to which they satisfy prototype semantic roles (proto-roles). Generally, proto-roles can be labeled and ranked as proto-agent > proto-patient (Dowty, Reference Dowty1991). For example, Table 1 illustrates that the subject argument of accusative verbs satisfies proto-agent properties, and the object argument typically satisfies proto-patient properties. Proto-agents are characterized by the degree to which the verb argument satisfies volition (the capacity to use one's will), sentience (the capacity to feel, perceive or experience), causation and self-propelled movement. Proto-patients are characterized by change of state, causal affectedness, stationary or incremental theme properties.

Table 1. The proto-agent and proto-patient properties of the subject and object arguments for verbs used in Exp.1 and Exp.2.

Notes. 1. List of accusative verbs used as experimental items: umarmen (to embrace/hug), bedienen (to serve) küssen, (to kiss); Sprechen (to speak); grüssen (to greet); anrufen (to call); treffen (to meet); einladen (to invite); verabschieden (to say goodbye); Fangen (to catch); anschreien (to shout at); Retten; (to rescue); gehen (to walk). 2. Some accusative verbs vary in the extent to which they satisfy proto-agent or agent properties, but each meets our criteria that the subject meets more proto-agent properties than the object, e.g., the subject of low transitive verb besuchen (to visit) satisfies volitional and sentience properties, whilst the object satisfies no properties. 3. List of dative verbs used as experimental items: imponieren (to impress) gefallen (to be pleased to), missfallen (to displease), auffallen (to notice).

Crucially, when the flexible word order of German is applied to dative object-experiencer verbs, such as imponieren “to impress”, the proto-agent aligns to the object argument whilst proto-patient properties align to the subject argument. Specifically, linguistics literature generally classifies and ranks the semantic arguments of dative object-experiencer verbs, as experiencer > theme (rather than agent > patient) (Dowty, Reference Dowty1991; Primus, Reference Primus1999). Table 1 illustrates this prominence hierarchy by showing that the (object) experiencer argument satisfies more proto-agent properties, and the (subject) theme argument satisfies more proto-patient properties. This affords an experimental design which can disentangle semantic from grammatical prominence cues. When these verbs are used, neither an SVO or OVS order align grammatical and semantic prominence cues, so the design can be used to inform whether one is more powerful in the overriding of order of mention effects. That is, in a dative-experiencer SVO construction, the first mention aligns with the subject, but these prominence cues converge with the low prominence theme (proto-patient); conversely, in an OVS order, the first mention aligns with the (proto-agent) experiencer argument, but these prominence cues also converge with the low prominence grammatical object. Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017: Experiment 2; also see Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Backhaus and Dangl2015, Reference Schumacher, Dangl, Uzun, Holler and Suckow2016) tracked adult gaze patterns for these sentences and revealed that order of mention preference was robust only when it aligned to semantic role (OVS order), whereas it meandered at chance when aligned with grammatical role (SVO order). Together with the findings for accusative verbs, their results were (i) in line with the well-established multiple-constraints perspective which posits that adult pronoun resolution is sensitive in varying degrees to different prominence cues (e.g., Arnold, Eisenband, Brown-Schmidt & Trueswell, Reference Arnold, Eisenband, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2000; Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005; Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008); and (ii) crucially provided specification, as afforded by their novel experimental design, that semantic role is the more dominant of these cues.

Whilst there is a theoretical consensus that grammatical role, order of mention, and semantic role also have a combinatorial influence on children's pronoun resolution, there is no empirical work that has used the aforementioned experimental design to fully disentangle them. Nevertheless, it should be noted that similar disentanglements via the German language have been successfully applied to investigate children's sentence-level understanding of referential expressions other than personal pronouns (see Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Kidd, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Dittmar et al., Reference Dittmar, Abbot-Smith, Lieven and Tomasello2008; Grünloh et al., Reference Grünloh, Lieven and Tomasello2011). The majority of VWP child studies with personal pronouns have used the English language, so their conclusions only cover that children as young as three years of age display interpretive preferences to an entity that converges as the first mention, subject, and agent (Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015; Pyykkönen, Matthews & Järvikivi, Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010; Song & Fisher, Reference Song and Fisher2005, Reference Song and Fisher2007). In fact, “first mention preference” is widely used by the child literature as an umbrella term to describe this preference for the converged prominence cues (Goodrich Smith & Hudson Kam, Reference Goodrich Smith and Hudson Kam2015; Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015). Importantly, time course data from these studies have shown that the time course of pronoun attachment is slower for children up to six-years-old compared to adults (>1000 ms after the pronoun onset; for review see Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015). The questions that follow become when and to what extent do children aged seven years and over (i) display adult-like magnitude and speed in their preferences when cues are aligned; and (ii) learn to distinguish these cues and develop weighting preferences?

To date, Pyykkönen et al. (Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010) conducted the informative study on whether children distinguish these cues. Despite using the English language, with the subject converging to the proto-agent and the object with the proto-patient, they manipulated the degree of the proto-agent properties of a subject argument and the degree of proto-patient properties of an object argument. For example, with high transitive verbs like hit, the subject satisfies each of the proto-agent properties, and all but one of the proto-patient properties are satisfied by the object (the exception being incremental theme). Conversely, for a low transitive verb like saw, the subject satisfies only two of the proto-agent properties (volition, sentience) and the object satisfies zero proto-patient properties. Pyykkönen et al. demonstrated that three-year-olds significantly reduced their looks to the object when it was the argument of a low transitive verb relative to a high transitive verb (resulting in a stronger subject preference with low transitives). The authors attributed this to the object argument of low transitive verbs not satisfying any proto-patient properties, concluding that semantic prominence cues modulate children's pronoun resolution (for a similar “object affectedness” explanation applied to the domain of acquiring syntactic argument structures, see Gropen, Pinker, Hollander & Goldberg, Reference Gropen, Pinker, Hollander and Goldberg1991).

The results of Pyykkönen et al. suggest that a multiple constraints framework can be extended to children (e.g., Arnold, Brown-Schmidt & Trueswell, Reference Arnold, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2007; Arnold, Castro-Schilo, Zerkle & Rao, Reference Arnold, Castro-Schilo, Zerkle and Rao2019; Järvikivi, Pyykkönen-Klauck, Schimke, Colonna & Hemforth, Reference Järvikivi, Pyykkönen-Klauck, Schimke, Colonna and Hemforth2014), such that subject and first mention interpretive preferences are strongest when aligned with the more prominent semantic role cue. Despite this, any experimental design that uses the English language can only modestly test the extent to which semantic prominence cues are weighted aside other cues. For example, in both the high and low transitive conditions, the first mention and subject were still both the proto-agent (i.e., a full alignment of three high prominence cues). As described above, less proto-agent properties were satisfied for the low transitive sentences; however, these elicited the earlier and more enhanced subject preference (this was attributed to low transitive sentences not satisfying any proto-patient properties). Indeed, even though it was less pronounced and occurred later (1760 ms to 2280 ms), the high transitive condition did elicit a significantly greater than chance preference for the subject (first mention and proto-agent) over the object (second mention and proto-patient). That is, the variation in how much the subject (and first mentioned) character satisfied the four proto-agent properties (high transitive = 4, low transitive = 2) only modestly tests the extent to which agentivity might drive preferences in the way it does for adults (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). The aforementioned German sentential contexts in which the proto-agent can align to the object argument and the proto-patient properties can align to the subject argument afford a design that can more fully disentangle semantic role from other prominence cues, which can in turn help determine the relative extent to which it is weighed – rather than merely conclude a sensitivity over and above the presence of other cues.

The present study

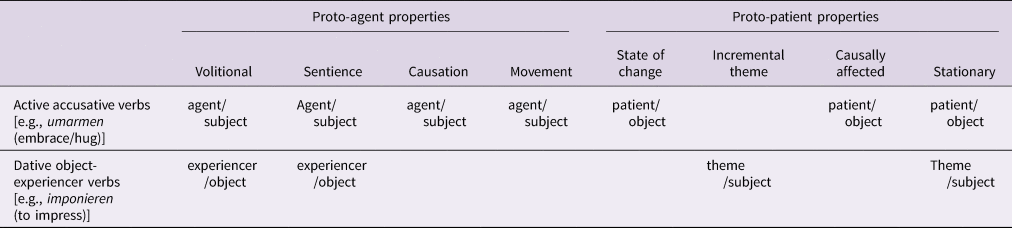

The present study is the first to date that directly teases apart the individual and combined effects of order of mention, grammatical role, and semantic role on children's real time processing of ambiguous pronouns. We have described some initial evidence for a multiple-constraints perspective, such that even 3-year-olds appear to combine these cues rather than use one alone (Pyykkönen et al., Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010). However, a more fine-grained multiple-constraints perspective must also specify whether children weight certain cues more than others, and whether such strategies follow a developmental pattern or are already adult like (Trueswell & Gleitman, Reference Trueswell, Gleitman, Henderson and Ferreira2004). For example, Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2007) reported that gender disambiguating cues (e.g., The fireman wants to rescue the girl but she is way too nervous) are used at an even younger age and more robustly than preferences for the converged prominence cues that we have discussed thus far (first mention, subjecthood and agentivity). This was interpreted as support to the notion that any linguistic (or non-linguistic) feature of a character in prior discourse that frequently co-refers with an unambiguous referential expression of later discourse can be learned via input as a pronominal cue: gender disambiguating cues offer a fully consistent mapping between the pronoun (e.g., she) and the referent (e.g., the girl), whereas the prominence cues emerge more gradually because their mapping is less reliable. By misaligning the three prominence cues, the present study can potentially identify unequal weightings and/or developmental patterns. If these weightings appear to be aligned to patterns of probabilistic regularities of input then, like the interpretation of data for younger children by Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2007), it could be indicative that these cues are not prominent by nature (see Song & Fisher, Reference Song and Fisher2005). We return to this in the General Discussion, with consideration to abstract frequency forms (see Abbot-Smith & Behrens, Reference Abbot-Smith and Behrens2006; Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland & Theakston, Reference Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland and Theakston2015; Kidd, Brandt, Lieven & Tomasello, Reference Kidd, Brandt, Lieven and Tomasello2007; Noble, Iqbal, Lieven & Theakston, Reference Noble, Iqbal, Lieven and Theakston2015). Table 2 summarizes the delineations made for each experimental condition of the present study and the predictions for which entity a pronoun would be attached to if each cue were considered alone.

Table 2. By-condition gaze preference looks that would be expected if children were driven by (i) order of mention (ii) grammatical role (iii) semantic role.

Notes. 1. Each of the 3 prominence cue columns bold print and underline the expected entity/feature that would be fixated, by each condition. 2. The two cues that converge with that entity/feature (see Note 1) are bracketed within the same cell [and are not bold printed or underlined, regardless of whether they (mis)align in prominence]. 3. Prominent cues are italicized, low prominent cues are not-italicized: if converging cues are aligned in prominence, they share (non-)italicization.

Further, we examine whether children's weighting of cues is form-specific: German allows for a comparison of different pronoun forms, so we compared performance on the unstressed personal pronoun er (similar to he), and the demonstrative (or d-) pronoun der. Adults typically link er to high prominence antecedents; whereas der is typically linked to low prominence antecedents (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Backhaus and Dangl2015, Reference Schumacher, Dangl, Uzun, Holler and Suckow2016, Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). This is attributed to theory that a referring expression with stressed form (e.g., der) signals forward shifting of the entity in focus, whereas a reduced phonological form (e.g., er) typically refers backwards to a currently focused entity so makes use of high prominence cues (Gundel, Reference Gundel2003). These forms effectively offer two ways of investigating the role and differential weightings of prominence cues in pronoun resolution and, in turn, whether these are form-specific (Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008). For example, the finding by Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017) that adult resolution is driven by semantic cues, held across er (which preferred the proto-agent) and der (the proto-patient), suggesting that this applies broadly across pronoun interpretive preferences. However, whilst semantic role was the more powerful cue when adults resolve both er and der, this appeared less pronounced for er – which attended to order of mention cues more than der does (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Therefore, the prominence hierarchy of multiple-constraints influencing er and der is not strictly complementary (Bosch, Katz & Umbach, Reference Bosch, Katz, Umbach, Schwarz-Friesel, Consten and Knees2007) but, rather, form-specific (Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008).

In two VWP experiments, seven- to ten-year-olds listened to German sentences with aligned or misaligned prominence cues, followed by a sentence containing the pronoun er or der. Specifically, we manipulated word order (SVO, OVS) and pronoun form (er, der), and applied this design to accusative verbs (Experiment 1) and dative object-experiencer verbs (Experiment 2). Comparison of these designs affords a disentangling of order of mention, grammatical role, and semantic role. Children's eye movements were tracked, and time locked to the onset of the ambiguous pronoun. Our use of a VWP provides a sensitive means to assess the participant's real-time preferred referent for an ambiguous pronoun, grounded in literature showing that listeners look toward an element depicted on the screen as they hear about it in the input (Altmann & Kamide, Reference Altmann and Kamide1999; Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Eisenband, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2000; Cooper, Reference Cooper1974; Ellert, Reference Ellert2011; Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005).

Our first prediction was in line with a straightforward multiple constraints account that, as for adults, children use a combination of factors. For this to be realized, we expected clearer preferences when prominence features align (SVO accusatives: Experiment 1); whereas preferences should be reduced when features are misaligned – reflecting a trade-off rather than having a single cue fully drive preferences regardless of other cues. Our second prediction was that, as for adults, er should more typically attach to high prominence entities whereas der should attach to low prominence entities. Considering these broad predictions together, we also explored whether our multiple-constraint prediction would be form-specific (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017) rather than equivalent across forms (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Katz, Umbach, Schwarz-Friesel, Consten and Knees2007). Our primary motivation was to explore whether seven- to ten-year-olds are already weighing semantic role as the most powerful cue in the same way adults do (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). The multiple-constraints prediction above assumes adult-like attachment preferences in general, but we also expected that children's fine-grained weighted preferences of cues would differ from adults. That is, whilst children might demonstrate sensitivity to each prominence cue (Pyykkönen et al., Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010), they may place greater reliance on an earlier-developed cue like order of mention, than on grammatical and semantic cues for which knowledge is likely to appear more gradually over time. Related, this may depend on the extent to which sentences follow the prototypical structural mapping of semantic roles (see General Discussion; Ambridge, Pine & Lieven, Reference Ambridge, Pine and Lieven2014; Goodrich Smith, Black & Hudson Kam, Reference Goodrich Smith, Black and Hudson Kam2019; Goodrich Smith & Hudson Kam, Reference Goodrich Smith and Hudson Kam2015).

Experiment 1

By using German active accusative verbs and flexible word order, Experiment 1 was able to disentangle order of mention (first vs. second) effects from grammatical role (subject vs. object) / semantic role (proto-agent vs proto-patient) effects. For an SVO order, the first mention is aligned with subject and agent features; conversely, an OVS order does not align first mention with either of these high prominence cues (see Table 2).

Method

Participants

Seventy-two children (mean age 8;9; range = 7;0–10;8, 37 boys) participated. All were monolingual speakers of German and none had reported language disabilities. Children were in three different school year groups: 29 children in second grade aged 7 to 8 (mean = 7;8; range = 7;0–8;6, 13 boys), 22 children in third grade aged 8 to 9 (mean = 9;0; range = 8;2–9;5, 13 boys), and 21 children in fourth grade aged 9 to 10 (mean = 10;0; range = 9;3–10;5, 11 boys). All children were based in the South West region of Germany. One child was excluded because they had over 50% track loss due to excessive moving during the experiment (the participant data reported above does not include that child). Written parental consent was obtained for all children, and children provided oral assent before each session.

Materials

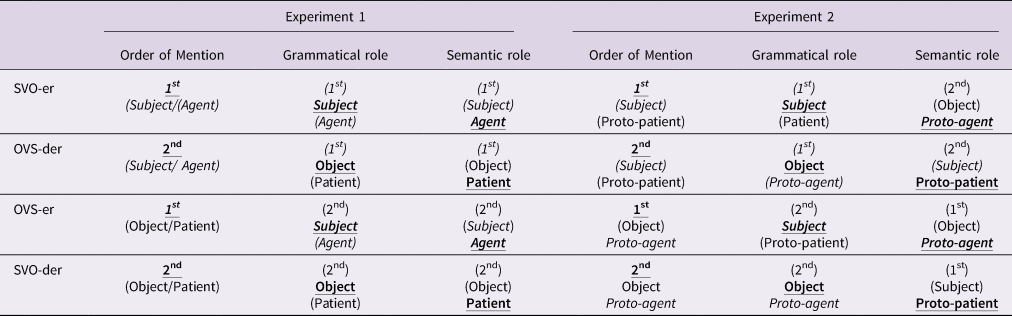

Sixteen experimental items were selected – a subset of the materials used by Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Each item represented two animate entities with masculine gender (e.g., trainer/coach and goalkeeper), and an inanimate entity or an animate character with feminine gender (e.g., cake, actress), which appeared in a narration and as images displayed on the screen. A context sentence was narrated which contained an active accusative verb, taking a subject (nominative) agent and an object (accusative) patient. The context sentence was narrated in either an SVO or OVS order featuring the animate male characters as the subject or object arguments, followed by a phrase containing the inanimate entity or female character as a final NP (e.g., cake, actress). The final NP was included so that participants would fixate on its image prior to a critical sentence region. Following Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017), the critical sentence began with aber “but”, followed by an ambiguous pronoun er or der. Each item was counterbalanced into four lists so that it would correspond to four experimental conditions, which were created by the crossing of our two binomial predictor variables: word order (SVO vs. OVS) and pronoun (er vs. der). Examples of these four conditions are given with translations in (2) below, with the subject/agent in bold print and the object/patient in italics. In (2a), the first mention, subject and agent are aligned (the goalkeeper); whereas in example (2b) the first mention is aligned with two low prominence cues (patient/object) (the trainer). Nevertheless, both examples have the same meaning.

(2) a. Contextual sentence in SVO order, followed by critical sentence (Aber er/der…)

Der Torwart will den Trainer umarmen, weil die Torte so lecker ist. Aber er/der ist wieder einmal viel zu beschäftigt.

“The-NOM goalkeeper (S) wants the-ACC coach (O) hug.”

“The goalkeeper wants to hug the coach, because the cake is so delicious. But he is once again too busy.”

b. Contextual sentence in OVS order, followed by critical sentence (Aber er/der…)

Den Trainer will der Torwart umarmen, weil die Torte so lecker ist. Aber er/der ist wieder einmal viel zu beschäftigt.

“The-ACC coach (O) wants the-NOM goalkeeper (S) hug.”

“The goalkeeper wants to hug the coach, because the cake is so delicious. But he is once

again too busy.”

Four practice items were also created, each corresponding to an experimental condition. Sixteen filler items differed because the critical sentence did not include a pronoun reference, as in example (3). The 16 filler items were each counterbalanced so that each list included eight SVO fillers and eight OVS fillers.

(3) Die Postboten tragen die Post mit ihren Fahrrädern aus. Für viele Leute sind wichtige Briefe dabei.

“The mail carriers deliver the mail by bike. There are important letters for many people.”

The display screen (see Figure 1) for all items counterbalanced the presentation of the two animate characters into the top left and top right hand corner of the screen. The inanimate distractor was presented at the bottom centre of the screen. Narrations were recorded by a male German speaker. In order to guard against potential acoustic differences between conditions, the final stimuli were constructed by cross-balancing the context and pronoun sentences in such a way that the same pronoun audio (for both er and der conditions) was used with SVO and OVS sentences; and vice versa, the same production of the SVO and OVS sentences were used in both pronoun conditions (er and der). The experiment was programmed and pseudorandomized using Experiment Builder and run using Eyelink 1000 in the remote mode, with a sampling rate of 500 Hz to monitor gaze locations every 2 ms (SR Research, 2020).

Figure 1. Display screen accompanying an example experimental item

Procedure

Each child individually took part in the experiment. First, the child was asked to preview and name the characters on the computer screen, one by one. Seated around 50 cm in front of the computer screen, the child began the session with a calibration and validation procedure. The child completed four practice trials to ensure that they understood the procedure. Thirty two short stories (from one of the four lists) were listened to via headphones while we recorded eye movements towards characters on a screen. The stories featured a contextual sentence with an active accusative verb [e.g., umarmen “to hug”; listed in Table 1] taking a subject and object argument (e.g., trainer, goalkeeper) in either an SVO or OVS order, which was followed by a critical sentence that contained either er or der. After each story, a grey screen was shown, and the next story only began when the child looked at a sun character positioned in the centre of the screen (a drift-correct calibration check). The task lasted no longer than 30 minutes and was administered in a quiet area within a school setting.

Design

A 2 x 2 within subjects design was used, with age as a continuous predictor. The two categorical predictor variables were word order (SVO, OVS) and (pronoun (er, der). The response variable was preference looks to the first mentioned character of the context sentence. This was measured for a period of 2000 ms from the onset of the critical sentence, and was calculated by looks to the first mentioned character subtracted by looks to the second mentioned character (for more details, see the data treatment subsection of the results).

Results

A series of Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs; see van Rij, Vaci, Wurm & Feldman, Reference van Rij, Vaci, Wurm, Feldman, Pirrelli, Plag and Dressler2019b) were fitted to the data using the package mgcv version 1.8-31 (Wood, Reference Wood2017), in the statistical environment R version 3.6.0 (R Development Core Team, 2019). GAMMs are essentially an extension to a mixed-effects regression method (GLMMs; Baayen, Davidson & Bates, Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008). The main difference is that GAMMs drop the assumption of a linear relationship between predictor and response variables, and thereby afford the modeling of nonlinear effects if required by the data. This is particularly relevant to examining the time course of when predictors have an effect on the response variable, because a linear increase or decrease in time series data is not typically followed accordingly by the response variable. Non-linear modeling of predictor terms is achieved through smooth functions, which allow the regression line (or interaction surface) to become “wiggly” if required by the data (Wood, Reference Wood2017).

As noted, GAMMs afford mixed effects under a similar rationale to GLMMs – for example, to simultaneously ensure that data is not averaged over participants or over items. Such random effects are typically structured using random smooths (e.g., by-participant, by-item). For example, a by-participant random smooth to the effects of time controls for (error) variance in the effects of time that would be due to specific participants, and does so by also modeling a non-linear trend if required by the data.

Treatment

The raw data was extracted into a sample report using Dataviewer (SR Research, 2020), and then pre-processed in the VWPre package version 1.2.3 (Porretta, Kyröläinen, van Rij & Järvikivi, Reference Porretta, Kyröläinen, van Rij, Järvikivi, Czarnowski, Howlett and Jain.2018). Time course (20 ms time bins) was defined within a 2000 ms time window following critical period onset (aber er/der…), with a 200 ms prior offset. The proportions of looks toward interest areas (within 20 ms time bins) were empirical logit-transformed using the function transform_to_elogit. Logit transformation distributes the values symmetrically around zero and provides an unbounded measure for the analysis (see Barr, Reference Barr2008).

Model fitting and evaluation

The model was fitted using a backward stepwise elimination procedure (e.g., van Rij et al., Reference van Rij, Vaci, Wurm, Feldman, Pirrelli, Plag and Dressler2019b). The inclusion of each term was evaluated using three criteria deemed to complement each other: (i) the estimated p value in the model summary; (ii) the Maximum Likelihood (ML) score comparison of model variants using the compare ML function in the itsadug package version 2.3 (van Rij, Wieling, Baayen & van Rijn, Reference van Rij, Wieling, Baayen and van Rijn2020); and (iii) visual inspections of the model, again using functions from the itsadug package. We used the mgcv function gam.check (and model comparisons) to check whether the non-linearity of the smooth (a “k” argument) needed to be increased from the default. The response variable was first mention preference looks (looks to first mentioned entity minus looks to second mentioned entity). Therefore, models assumed a Gaussian distribution.

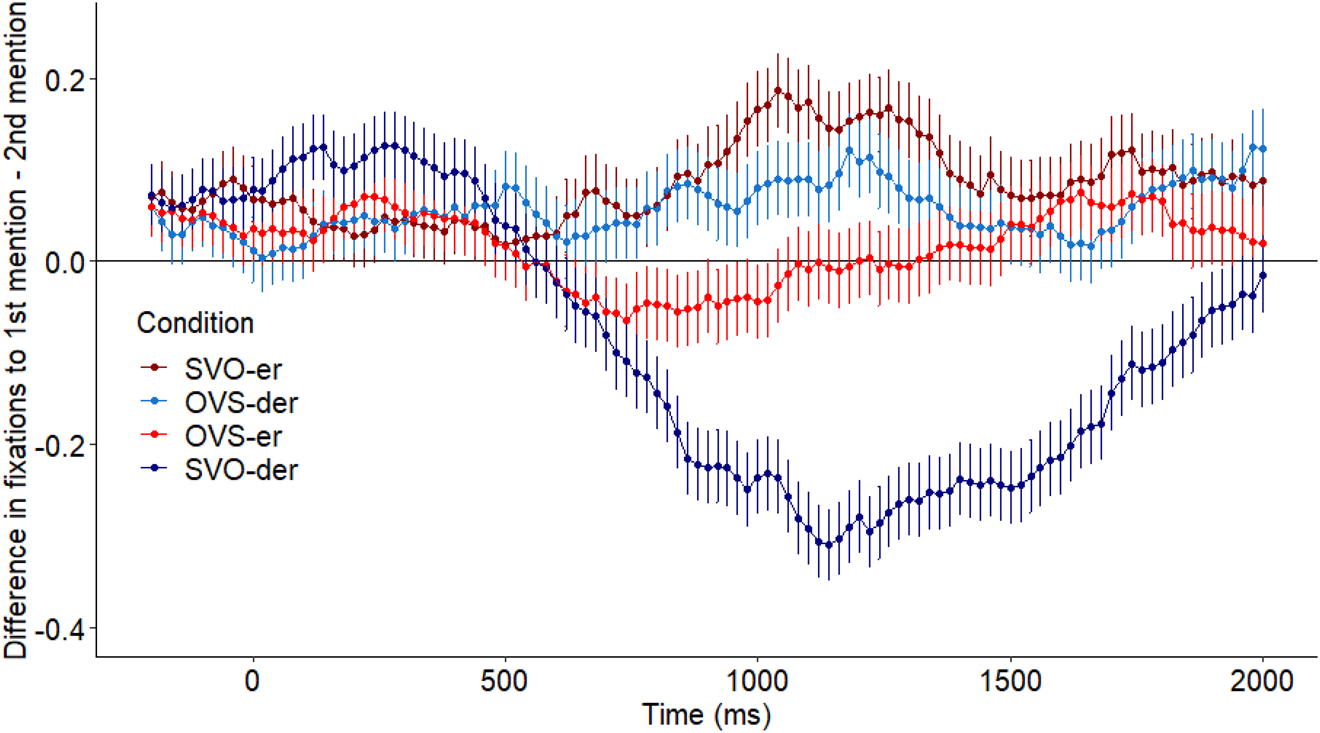

The aim of the initial model was to incorporate by-Participant and by-Item random smooths of Time. Due to later inspection of autocorrelation in the residuals, we also incorporated by-Event random intercepts (i.e., unique Participant and Item combinations) and by-Event random slopes to Time (see van Rij et al., Reference van Rij, Vaci, Wurm, Feldman, Pirrelli, Plag and Dressler2019b; Wieling, Reference Wieling2018). Autocorrelation was further accounted for by using an AR1 model (see Wood, Reference Wood2017). The experimental condition was fitted as a parameter coefficient predictor (akin to linear fixed effect terms): four categorical levels with SVO-er as the reference level (SVO-er, OVS-er, SVO-der, OVS-der sentences). In addition, the following predictors were included as non-linear smooths, and were allowed to interact: Condition (categorical, as above), Time course (continuous), and Age (continuous). The final model did not include Age terms because it did not significantly contribute to that model, nor did it sufficiently meet inclusion criteria via the model summary or visuals. Whilst interpreting the optimum-fit model (see below), it is useful to examine the grand means plot, where a positive score indicates first mention preference and a negative score indicates second mention preference (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Experiment 1 grand means plot of by-sentence condition looks to the DV (1st mention preference looks (looks to 1st – looks to 2nd) – where a positive score indicates 1st mention preference and a negative score indicates 2nd mention preference).

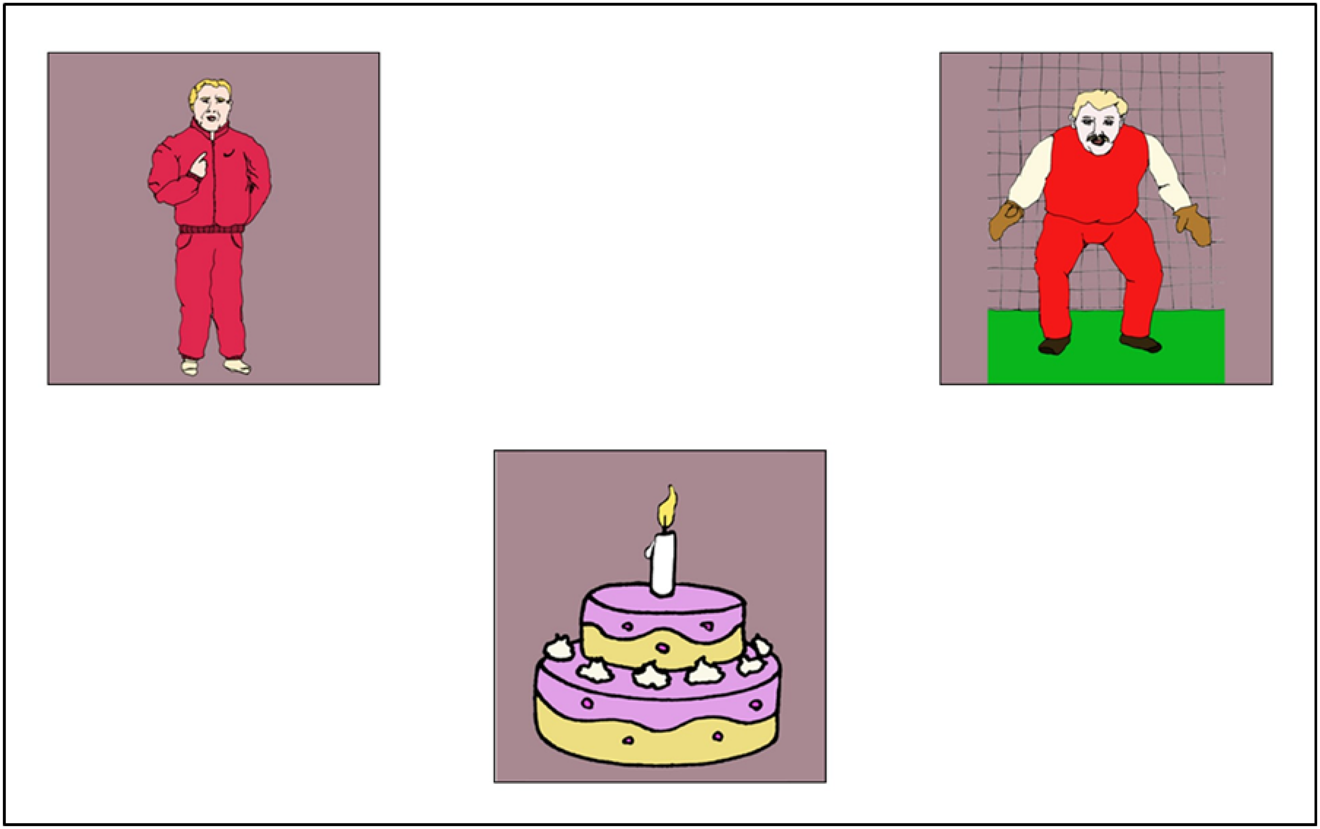

Summary and visualizations of optimum-fit model

Table 3 provides a summary of the inferential statistics for the optimum-fit model. The parametric coefficients can be interpreted in a similar fashion to GLMMs, such that the p value indicates whether a sentence is significantly different from the referent level (SVO-er), with a positive Estimate value indicating a stronger first mention preference and a negative estimate value indicating a weakened first mention preference (relative to the reference SVO-er). The parametric coefficients revealed a significant intercept value, indicating that there was a significantly greater than chance subject preference for SVO-er sentences. Relative to the SVO-er sentences (reference condition), looks to the first mention were weakened in each condition, but that this was significant only for the SVO-der sentences. However, these do not take the effects of time course into account.

Table 3. Final Generalized additive mixed model for Experiment 1. Reporting parametric coefficients (Part A) and effective degrees of freedom (edf), reference degrees of freedom (Ref.df), F and p values for the smooth and random effects (Part B)

Notes. R-sq.(adj) = 0.26; Deviance explained = 27%; -ML = 173910; n = 137943.

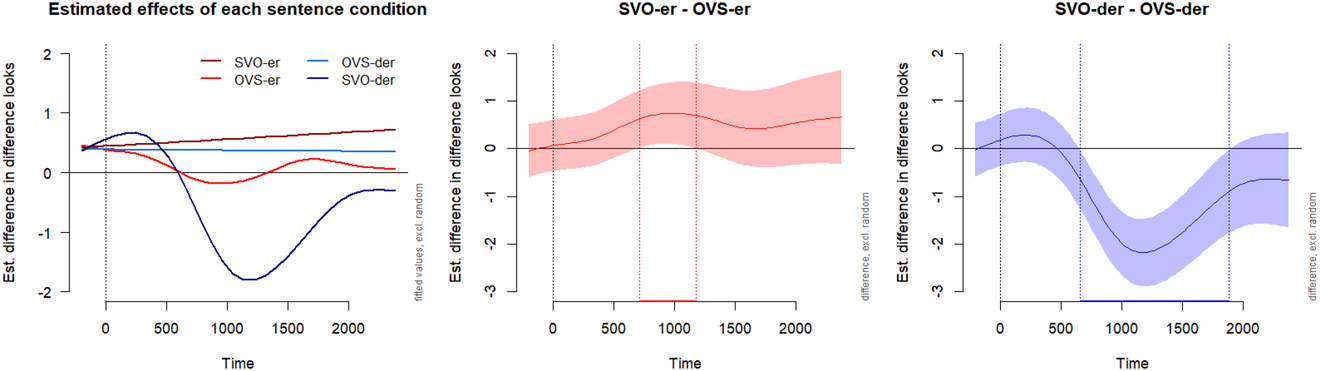

For the smooth terms, the “edf ” column stands for the number of effective degrees of freedom (an estimate of how many parameters are needed to represent the smooth); note that a value near one reflects linearity whereas, the greater a value is beyond one, the more it reflects non-linearity in the smooth (see Wieling, Reference Wieling2018). The smooth terms indicate that the smooth for SVO-der sentences is non-linear and significantly differs from zero at any point in time. The shape of this is visualized in the summed effects plot in the left panel of Figure 3, which also features the smooths for the three other sentence conditions that each were not significantly differ from chance.

Figure 3. Visualization of the summed effects derived from the optimum-fit model of Experiment 1, with the random effects set to zero. Left panel: Smooth terms for each time by condition term. Centre and Right panels: Difference plots visualizing the effect of word order whilst holding pronoun form constant (Centre = er; Right = der). Note. For the difference plots (centre and right), the solid colored line represents the estimated difference (with color shading for pointwise 95% confidence intervals) between the SVO and OVS sentences, and the dashed vertical colored line represents any time window for which this difference is significant. Consistent with the grand means (Figure 2) and smooth terms plot (Figure 3: left), er sentences are colored in red to reflect their typical association with prominent cues, and der sentences in blue to reflect their typical association with low prominence cues.

Further model visualization via difference plots (from the itsadug package) was essential in order to examine whether smooth terms significantly differ from one another. These take the response variable value for an SVO order sentence (difference score: first minus second) and subtract it by the corresponding value for the OVS sentence; therefore a positive value (above zero) indicates that first mention preference was greater in the SVO condition (i.e., the score for OVS was too small to subtract it into a negative value) whereas a negative score (below) zero indicates the first mention preference was greater in the OVS condition (i.e., the score for OVS is larger than SVO, resulting in a negative value). There was an effect of word order in both the er subset (Figure 3: centre) and the der subset (Figure 3: right). The centre panel shows that, whilst holding the pronoun form er constant, there was a significant preference for the first mentioned entity upon the SVO word order relative to the OVS word order, specifically between 712 ms to 1180 ms. Conversely, the right panel reveals that, whilst holding der constant, there was a significant preference for the second mentioned entity upon the SVO order relative to the OVS word order, specifically between 660 ms and 1880 ms. This suggests a cross-over interaction between word order effect and pronoun, such that word order effects occur in opposite directions within each pronoun form condition. This interaction is implemented in the four-level factor Condition, which is the conventional method to arrive at and report the optimum-fit model for a 2×2 experimental design like ours (see van Rij, Hendriks, van Rijn, Baayen & Wood, Reference van Rij, Hendriks, van Rijn, Baayen and Wood2019a; Wieling, Reference Wieling2018).

Note that a complimentary ordered factor model was also required to confirm that the interaction is significant over and above two main effect smooths via summary statistics. This is not possible to confirm from the Table 3 summary statistics because the order and pronoun predictors are present in every condition of the four-level condition smooth term (i.e., an identifiability problem). The complimentary modeling process first re-coded the word order effect as a binary predictor “IsOrder_SVO”, which was modeled as one smooth that is equal to zero whenever the order is SVO (reference) and as a (non)linear pattern whenever the order is OVS, thereby modeling a constant difference between the two levels. The same re-coding strategy was applied to pronoun effects (“IsPronoun_der”) and the interaction (Isder_SVO). Therefore, the four regression smooths for each of the four conditions (i.e., Table 3) were replaced by a reference smooth and three binary difference smooths implementing the effects of word order, pronoun and their interaction. That is, the term Isder_SVO implements the interaction effect that models the difference between the conditions SVO-der and OVS-der (in addition to the main effects of IsDer and IsSVOorder). This is reported in the Appendix (Table A.1). Consistent with the difference plots from the main modeling process (Figure 3, derived from the model reported in Table 3), Table A.1 offers summary statistics that indicate the effects are qualified by a significant word order by pronoun interaction. There was no main effect, confirming that the interaction was a cross-over interaction and not a “boost” interaction (the latter being an interaction where order effects would be in the same direction but more pronounced in one pronoun subset than the other).

Discussion

As with previous adult studies (e.g., Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017), children had clearer attachment preferences when prominence features were aligned (SVO sentences). For er sentences, a preference for the prominent first mentioned entity in SVO sentences was significantly weakened when that entity was aligned with the two low prominence cues in OVS sentences (object and patient). For der sentences, a significant preference for the low prominence second mentioned entity in SVO sentences was significantly weakened when that was aligned with two high prominence cues in OVS sentences (subjecthood and agentivity). That is, a first mention preference for SVO-er and a second mention preference for SVO-der were each significantly weakened under conditions in which the cues were misaligned (OVS order). This indicates that children, like adults, appear to use a combination of factors to resolve pronouns: if order of mention cues were enough alone to drive pronoun resolution, then the preferences in SVO sentences would have held equally as strong under misaligned OVS conditions.

Children's weighting of cues to guide their attachment preferences for er map neatly onto a previous corresponding experiment with German adults by Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017): the first mentioned entity was preferred for SVO-er, whereas performance meandered around chance level for OVS-er. To some extent, children's weightings of cues for der differed to Schumacher et al.'s adults: whilst word order effects within der sentences were in the same direction and reached significance (described above), our children's preferences in OVS-der meandered around zero which differs to adult preferences in these sentences for the object/patient (first mention). This suggests that, as for adults, the data fits a form-specific multiple-constraints framework (Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008) such that differential weightings for certain prominence cues were a more robust finding for demonstrative pronouns than for personal pronouns. However, children appeared to give greater weighting for order of mention cues to der, whereas the previous adult studies have indicated greater weighting is given for grammatical and/or semantic role.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2 the context sentence used dative object-experiencer verbs such as imponieren “to impress”, which take a subject (nominative) proto-patient argument and an object (dative-experiencer) proto-agent argument. This compliments the design of Experiment 1 because it affords an investigation into whether the reported influence of grammatical role and semantic role on interpretive preferences can be teased apart from each other.

Method

Participants

Sixty-four children (mean age 9;1; range = 7;5–10;8, 27 boys) participated, with the same selection and consent/assent criteria to Experiment 1. Participants were based in South West Germany. Children were in three different school year groups: 21 children in second grade aged 7 to 8 (mean = 8;1; range = 7;5–8;8, 6 boys), 22 children in third grade aged 8 to 9 (mean = 9;1; range = 8;2–9;9, 10 boys), and 21 children in fourth grade aged 9 to 10 years (mean = 10;1; range = 9;7–10;8, 11 boys).

Materials

As in Experiment 1, we manipulated word order and pronoun, shown in example (4) with an English translation to show they have the same meaning. To illustrate this, the proto-agent/object (dative-experiencer) is bold printed, and the proto-patient/subject (nominative) is italicized. In the SVO order, the proto-agent (dative-experiencer) is aligned with two low prominence cues (2nd mention, object). Conversely the OVS order aligns the subject with two low prominence cues (2nd mention, proto-patient). Note that with regards to word order for German sentences containing dative object experiencer verbs, OVS is taken to be the canonical argument order (dative-nominative) in the literature on German syntax (Haider, Reference Haider1993).

(3) a. Contextual sentence in SVO order, followed by critical sentence (Aber er/der…)

Der Kapitän gefällt dem Gärtner, der ein Eis isst. Aber er (der) redet gerade mit zwei Damen.

“The skipper-NOM is-pleasing-to the gardener-DAT who an ice cream eats. But he-NOM (DEM-NOM) talks now with two ladies.”

“The skipper is pleasing to the gardener who eats ice cream. But he is talking to two ladies right now”

b. Contextual sentence in OVS order, followed by critical sentence (Aber er/der…)

Dem Gärtner gefällt der Kapitän, der ein Eis isst. Aber er (der) redet gerade mit zwei Damen.

The-DAT gardener is-pleasing-to the-NOM skipper who an ice cream eats.

“The gardener-DAT is-pleasing-to the skipper-NOM who an ice cream eats. But he-NOM (DEM-NOM) talks now with two ladies”

“The skipper who eats ice cream is pleasing to the gardener. But he is talking to two ladies right now.”

The construction of materials aligned to Experiment 1, with the difference that fewer verbs were available because there is a relatively lower frequency of suitable German dative object-experiencer verbs that take two animate arguments. Therefore, the following four verbs were used for all items: gefallen “to be pleasing to”, auffallen “to notice”, missfallen “to displease”, imponieren “to impress”.

Procedure and design

The experimental procedure and design used in Experiment 1 were applied here.

Results

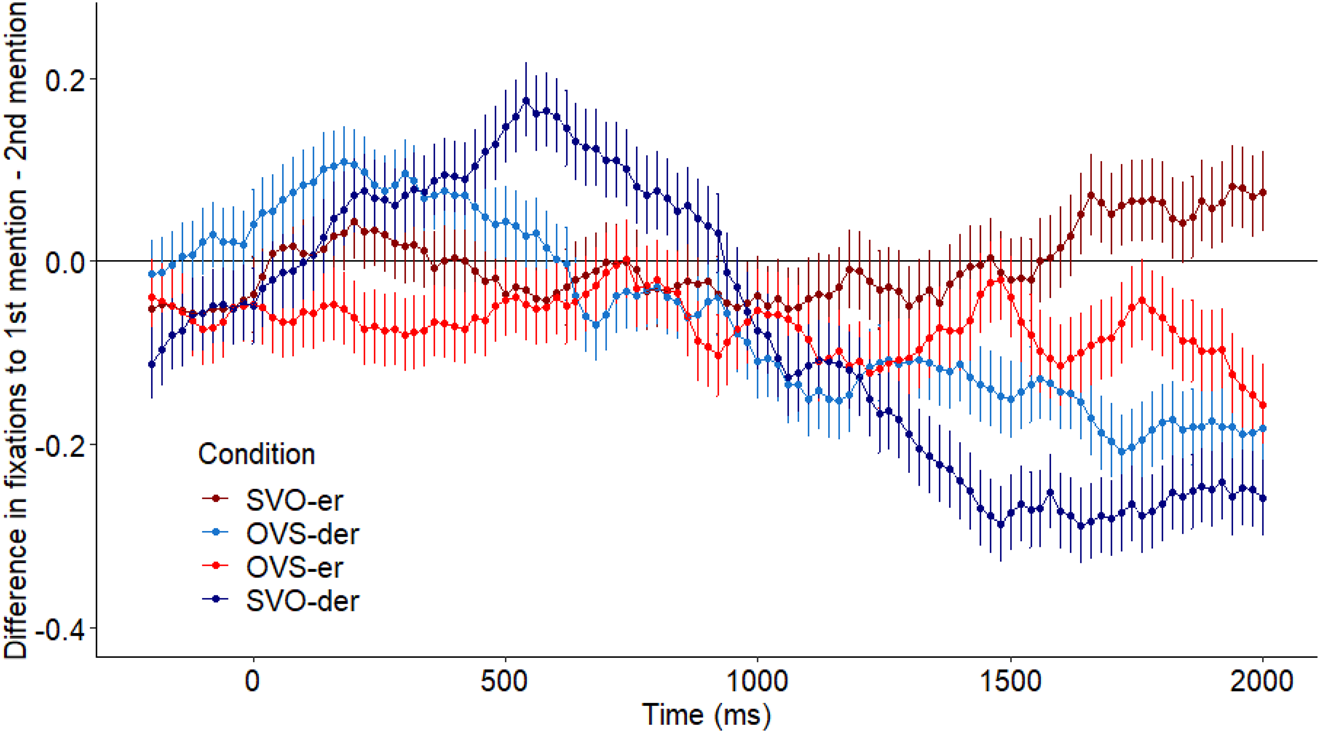

The same modeling process as Experiment 1 was used. The optimum-fit model differed from that used in Experiment 1 because Age terms met inclusion criteria via the model summary, comparisons, and visuals. Figure 4 provides the grand means plot.

Figure 4. Experiment 2 grand means plot of by-sentence condition looks to the DV (1st mention preference looks (looks to 1st – looks to 2nd) – where a positive score indicates 1st mention preference and a negative score indicates 2nd mention preference).

Summary and visualizations of optimum-fit model

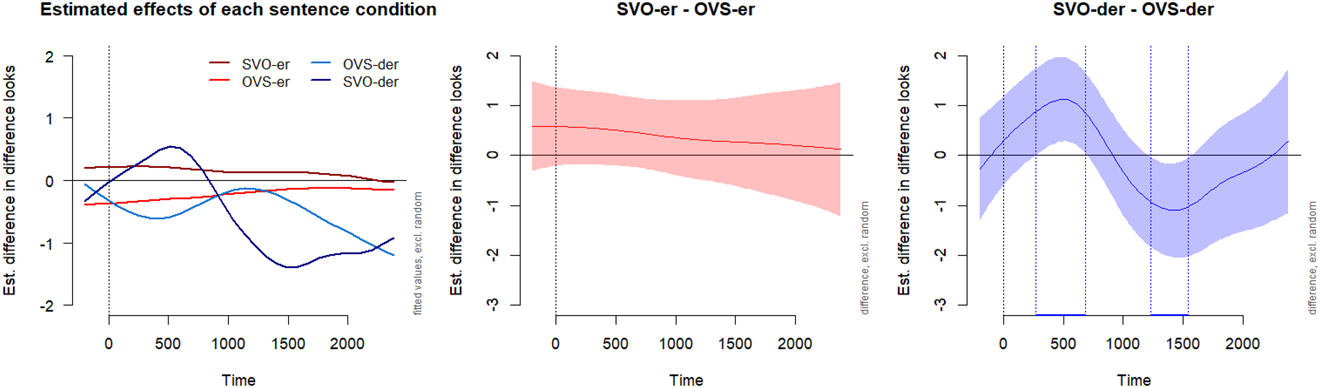

Inferential statistics for the optimum-fit model are provided in Table 4. The parameter coefficients revealed a non-significant intercept, and that the SVO-er sentences (reference condition) did not significantly differ from other conditions. The smooth terms are more interpretable because they take account of the time course of effects. The Time by Condition smooth indicated a significant non-linear trend away from zero for SVO-der sentences (see left panel of Figure 5 for a visualization of time by condition smooth terms). None of the smooth terms for Time by the other three sentences differed significantly from zero, nor did the age by condition smooth terms.

Table 4. Final Generalized additive mixed model for Experiment 2. Reporting parametric coefficients (Part A) and effective degrees of freedom (edf), reference degrees of freedom (Ref.df), F and p values for the smooth and random effects (Part B)

Notes. R-sq.(adj) = 0.27; Deviance explained = 28%; -ML = 140890; n = 111623.

Figure 5. Visualization of the summed effects derived from the optimum-fit model of Experiment 2, with the random effects set to zero. Left panel: Smooth terms for each time by condition term. Centre and Right panels: Difference plots visualizing the effect of word order whilst holding pronoun form constant (Centre = er; Right = der).

Further model visualization via difference plots (from the itsadug package) was essential in order to examine whether smooth terms significantly differed from each other. The centre panel of Figure 5 reveals no significant word order effects whilst holding the pronoun form er constant. The right panel demonstrates that, whilst holding der constant, there was a short but significant preference for the second mentioned entity upon the SVO order relative to the OVS word order, specifically between 1230 ms to 1550 ms (there was also an early first mention preference prior to the pronoun onset at 270 ms to 690 ms, which timing attributes to the connective aber, similar to but). As in Experiment 1, the Appendix reports a complimentary model that replaced by-condition smooths with binary predictors for the word order, pronoun and interaction effects (see Table A.2, Appendix). This compliments our (visual) interpretation of the main modeling process (Table 4, Figure 5). A main effect of pronoun was significant, indicating that children looked more to the second mention for der than for er sentences. The significant interaction term confirmed that the second mention preference for der sentences was more pronounced in the SVO order relative to OVS order (i.e., significant order effects in der sentences).

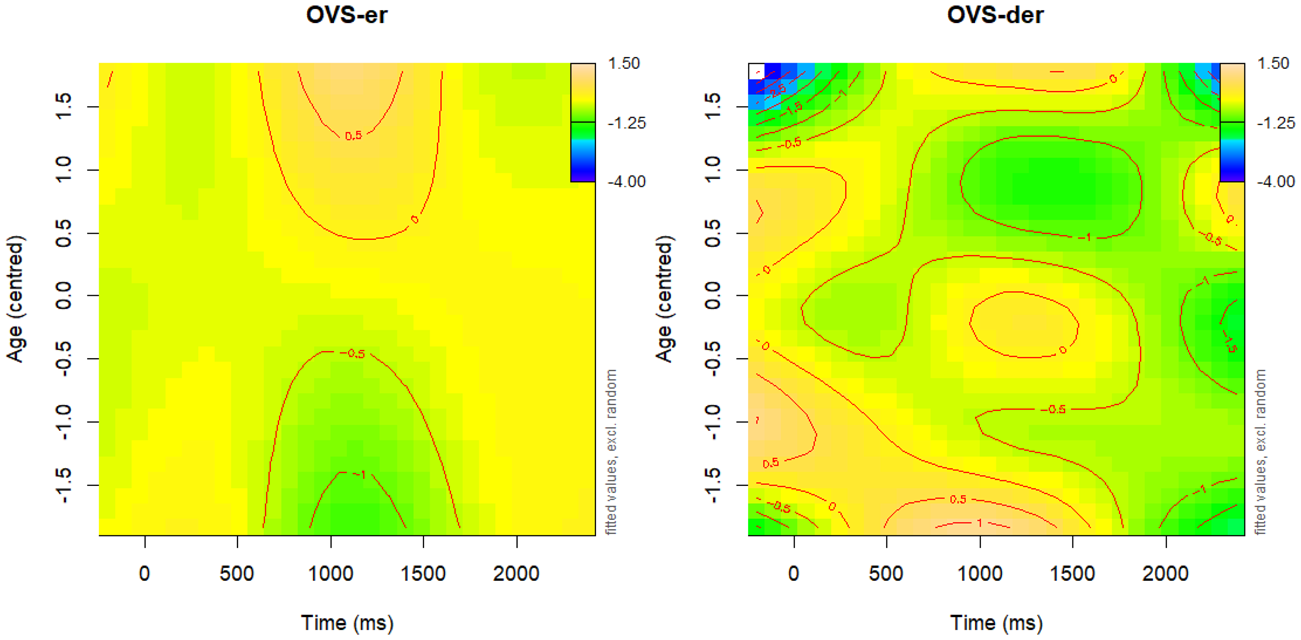

We do not report difference plots for the age by condition interaction because these were non-significant. However, there were two significant three-way terms in the model summary statistics (Table 4), specifically suggesting an age modulation of time course effects in the OVS-er (Figure 6: Left panel) and OVS-der (Figure 6: Right panel) conditions. Note that OVS-der had a more robust p-value and visualization, whereas OVS-er is a weak (but significant) effect. Contour plots in Figure 6 visualize how Time and Age modulated gaze preferences (first vs second mention preference) for these conditions. They read like a map, and have been scaled from a tendency to meander between zero and first mention preference (darker yellow signifying stronger preference) to a strong second mention preference (green). For OVS-er sentences (weaker interaction), the yellow coloring begins at around 500 ms for the older children, but does not develop in the youngest children until around 1500 ms. This suggests older children have more tendency to attach er using the aligned prominence cues of first mention and proto-agent, rather than the high prominence subject cue (which is aligned to the second mention and proto-patient cues). In OVS-der sentences, a block of green coloring (signaling looks to second mention, proto-patient, subject) appears from around 500 ms for older children, but from around 1500 ms for the younger children.

Figure 6. Contour plots of three-way interactions between Time (x-axis) Age (y-axis) and OVS-er (left panel) and OVS-der (right panel). Green indicates a second mention preference whereas yellow indicates a more neutral preference with a small tendency toward first mention preference (aligns to object/proto-agent for these OVS sentences).

Discussion

While the findings again show that children combined all three prominence cues, there were two notable indicators that their performance differed from that of adults in previous studies.

First, children's attachment preferences for er sentences meandered around zero, regardless of word order. This was not surprising for SVO-er sentences, as adults perform similarly. Where children's performance differed from previous adult findings for er was by not displaying a preference to attach OVS-er to the (first mention) proto-agent, instead meandering around zero. Note that this nevertheless supports findings for Experiment 1, such that once cues for resolving er are misaligned, they trade off against each other fairly equivalently, suggesting that children have not yet developed weighted preferences for specific cues. However, the three-way interaction of Time:Age:OVS-er suggests that children are developing preferences in the same direction as those of adults: older children displayed an increase in use of order of mention and/or semantic cues over grammatical cues. This aligns to our prediction that the data would reveal a gradual development toward adult-like weighted preferences. Note that, as above with personal pronouns, children's preferences for OVS-der evidence a gradual shift toward weighting order of mention and/or semantic cues over grammatical cues. Specifically, older children had more tendency to attach der using the aligned low prominence cues of second mention and proto-patient, rather than the low prominence object cue (which was aligned to the first mention and proto-agent cues).

Second, whilst children appeared adult-like in attaching OVS-der toward the (second mention) proto-patient, it was surprising that their second mention preference for der was significantly greater for SVO-der sentences which do not align the second mention to the proto-patient. This indicated that the second mentioned entity was the most powerful low prominence cue that der was attracted to (as supported by the main effect of pronoun in Table A.2). Note that the earlier and more robust timing effects of SVO-der in Experiment 1 when the proto-patient cue was aligned with the two other low prominence cues (from 600 ms, rather than 1200 ms when misaligned in Experiment 2) are indicative that semantic role still has a strong influence (like adults). However, the small but significant pronounced preference for second mention in the SVO-der versus OVS-der conditions still needs an explanation beyond the general second mention and proto-patient preferences. Whilst this could be an influence of objecthood (grammatical role), we further interpret this in the General Discussion.

General Discussion

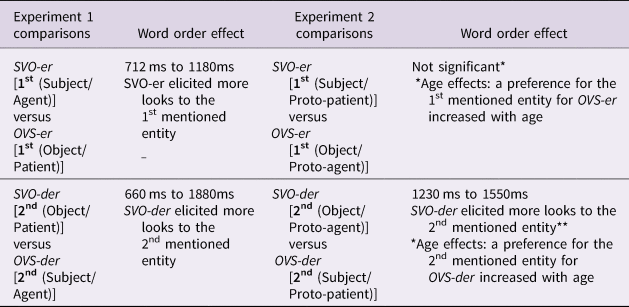

This study was designed to investigate German speaking 7- to 10-year-old children's use of different prominence cues in their interpretation of ambiguous personal pronouns (er) and d-pronouns (der). Our findings extend the understanding of children's pronoun interpretation strategies in several important ways. First, we show that, like adults, children use a combination of prominence cues rather than one cue alone to resolve both er and der, which supports a multiple constraints perspective (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Eisenband, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2000; Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008; Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel, Hyönä and Bertram2005; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Second, we find that children more typically attach er to high prominence entities and der to low prominence entities, further demonstrating adult-like preferences (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Third, performance with sentences containing misaligned cues revealed that, whilst semantic cues clearly influence performance and are weighted more heavily with increasing age, these are not yet the most powerful drivers of preferences, indicating that even 10-year-olds are still developing their weightings toward an adult-like level. Instead, children appear to rely more on order of mention cues (Goodrich Smith et al., Reference Goodrich Smith, Black and Hudson Kam2019; Goodrich Smith & Hudson Kam, Reference Goodrich Smith and Hudson Kam2012). This was particularly robust for der relative to er, which supports a form-specific multiple constraints account, such that weighted preferences for these cues do not apply equivalently across reference forms (Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Note that Table 5 summarises our results, further illustrating the alignment of prominence cues in each condition.

Table 5. Summary of results for Experiments 1 and 2. The effect of word order on looking preferences whilst holding pronoun form constant (as revealed by difference plots in Figures 3 and 5): er comparisons = SVO-er versus OVS-er, der comparisons = SVO-der versus OVS-der.

Notes. 1. In the ‘comparison’ columns, we bold print the entity that would be expected to be fixated upon according to order of mention (1st for er sentences, 2nd for der sentences). The other two cues of interest that converge with that order of mention entity/feature are circle bracketed.

Children used a combination of order of mention, grammatical role, and semantic role to resolve pronouns. One way that this was displayed was through clear preferences around the pronoun onset (i.e., early) in sentence conditions that fully aligned prominence features (SVO accusatives): children showed a preference to attach er to entities that carried aligned high prominence features (first, subject, agent), and robust preferences to attach der to entities with aligned low prominence features (second, object, patient). Another demonstration of this was that preferences were generally weaker in sentences that misaligned prominence features. Taken together, this is in line with a straightforward multiple-constraints framework such that no single prominence cue fully accounted for pronoun resolution, as has been reported for adults (e.g., Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). The influence of semantics speaks against a purely structural explanation of children's performance, as has been reported in developmental literature on broader aspects of language acquisition (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Kidd, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Lieven and Tomasello2009; Dittmar et al., Reference Dittmar, Abbot-Smith, Lieven and Tomasello2008). Whilst this has been suggested by previous child studies (Pyykkönen et al., Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010), the present study is the first to have fully disentangled these three cues to reveal that each influences children's pronoun resolution independently.

We now turn to understanding the extent to which children distinguish these cues and whether they have developed adult-like weighting preferences. Perhaps the most important sign of adult-like differential weighting of the cues was an independent influence of semantic role (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Our results indicated that children use semantic role information even when it is put into conflict with other cues, building upon previous child pronoun studies (Pyykkönen et al., Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010). First, the finding in Experiment 1 – that preferences for entities with fully aligned cues (er: first, subject, agent; der: second, object, patient) were weakened in OVS conditions – confirmed that grammatical role and/or semantic role significantly traded off against order of mention cues. Crucially, performance with dative object-experiencer verbs (Experiment 2) determined that effects of semantic role can occur independent of grammatical role. That SVO-er meandered at chance contrasts with the tendency reported in Experiment 1 to attach SVO-er to the first mention. This indicates that children used semantic role in their resolution of er: unlike in Experiment 1, the prominent agent was not aligned to the first mention and subject. This maps onto adult performance that has been previously reported for SVO-er sentences (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). We should also note that, whilst OVS-er dative object-experiencers overall meandered at chance rather than showing an adult-like preference for the proto-agent (first mention, object), older children were significantly more likely to choose the proto-agent than younger children. With regards to semantic role influencing the resolution of der, results mirror the previously reported adult studies on the crucial OVS-der dative object-experiencer sentences: children resolved der toward the (second mention) proto-patient despite it being misaligned with grammatical role. This indicates that order of mention preferences for der are present when aligned with semantic role, which is important because Experiment 1 indicated that order of mention cues are not powerful enough on their own to drive der preferences. Further, this OVS-der pattern was more likely to be displayed by older children, indicating developmental improvements toward an adult-like resolving of der to the proto-patient.

In the Introduction, we outlined that the most common finding in previous work with children and ambiguous (personal) pronouns is a first mention preference (Goodrich Smith & Hudson Kam, Reference Goodrich Smith and Hudson Kam2012; Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015; Pyykkönen et al., Reference Pyykkönen, Matthews and Järvikivi2010; Song & Fisher, Reference Song and Fisher2005, Reference Song and Fisher2007). However, to our knowledge, no previous study had directly disentangled order of mention from grammatical role or semantic role. In our study, order of mention cues for er (first) were associated with interpretive preferences, but only when aligned to semantic and/or grammatical cues (i.e., Experiment 1: SVO), and not under any misaligned conditions (Experiment 1: OVS; Experiment 2 SVO, OVS). Order of mention cues (second) for der were the most robust preference reported: both SVO- and OVS-der were resolved to the second mentioned entity. This shows that, whilst order of mention cues were not enough on their own to drive interpretative preferences of der (Experiment 1: OVS), they did have a clear influence when aligned to any other prominence cue (semantic role: OVS-der; grammatical role: SVO-der). We further interpret these findings as evidence of form-specificity (Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, van Gompel and Hyönä2017; Kaiser & Trueswell, Reference Kaiser and Trueswell2008; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017) such that the influence of cues was differentially weighted for er versus der. Most notably, relative to der, interpretative processes for er appeared more weakened by any misalignment of cues, which indicates more reliance on the intertwining of each cue and more competition between each misaligned cue. We encourage future studies to investigate to what extent these findings apply to younger children, but re-emphasize that our age window was of most interest for tapping into the initial developmental patterns toward an adult weighting of cues.

It is important to note that children's form-specificity described above is attributed to weighted preferences in a different way from form-specificity reported in adult literature (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Roberts and Järvikivi2017). Specifically, even 10-year-olds are not yet weighting semantic role as the most powerful cue in the same way adults do. The likely reason for this is that our age group is in a developmental window where the knowledge of semantic role (and grammatical role) is becoming more sophisticated, specifically with regard to strategic use in pronoun resolution. This is demonstrated by the aforementioned age modulation of preferences in Experiment 2: older children were more likely than younger children to use semantic role in an adult-like manner for resolving OVS-der (to proto-patient, second mention) and OVS-er (to proto-agent, first mention).

The only sentence condition that children resolved in a manner that directly contrasts with the adult-like use of semantic role was dative object-experiencer SVO-der sentences (Experiment 2), for which they displayed strong preferences to the second mentioned entity (object), even though the low prominence proto-patient cue was the first mentioned entity (subject). We should note again that attachment to the second mention was also strong for fully aligned SVO-der sentences with accusative verbs (Experiment 1) and word order effects occurred earlier (600 ms, not 1200ms), suggesting that the misalignment of semantic role cues might slow down interpretative preferences. Nevertheless, SVO-der dative object-experiencer sentences were resolved to the second mention more than OVS-der sentences. One reason for this is that the former are assumed to have a non-canonical argument order (nominative-dative) by German syntax literature (Haider, Reference Haider1993), so that inherent structural complexity might simply make children more likely to default to a simplistic order of mention strategy.

An important fact to consider in any explanation, however, is that dative object-experiencer verbs have relatively low frequency in speech directed to children. For example, only 208 instances of dative object-experiencer verbs are present in the nearly 2 million words of CDS spoken to children aged 2;5 to 7;0 in two large corpora in CHILDES (Leo corpus: Behrens, Reference Behrens2006; Rigol and Wagner corpus: Wagner, Reference Wagner1985). Therefore, we suggest that the above explanation needs to be extended and in turn related to a frequency-based framework of children's pronoun understanding (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2007). Specifically, a proposed defaulting to a simplistic order of mention strategy must to some extent apply for all word orders containing (infrequent) dative object-experiencer verbs – which fits our data that children have not yet reached a mature weighting of semantic cues. We adopt a constructivist argument that considers frequency effects not strictly in terms of construction type per se (see Abbot-Smith & Behrens, Reference Abbot-Smith and Behrens2006; Ambridge et al., Reference Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland and Theakston2015; Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Brandt, Lieven and Tomasello2007; Noble et al., Reference Noble, Iqbal, Lieven and Theakston2015). Specifically, the low frequency of these verbs should be an issue with regard to exposure to their unique structural mapping of semantic roles. In terms of a simple NOUN-VERB-NOUN schema the most prototypical structural mapping of semantic roles to which German children are exposed is with high frequency verbs such as active accusatives (where SVO order is more frequent than OVS order), whose proto-agent maps onto the first mention/subject. A constructivist account would argue that NOUN-VERB-NOUN representations might initially be restricted to the most prototypical structural mapping of semantic roles (agent = first mention/subject), which gradually broadens to incorporate moderately frequent mappings including those for OVS active accusatives (agent = second mention/subject). Later (or more gradually) the schema broadens out to incorporate the unique structural mapping of semantic role offered from lower frequency dative object-experiencer verbs [OVS: proto-agent = first/object; SVO: proto-agent = second/object]. The lack of exposure and relatively fragile representations of the semantic mappings for object-experiencer verbs would lead children to often interpret these sentences with schemas from more frequent prototypical mappings. For example, one can argue that SVO carries the least prototypical mapping with consideration to semantic role, as it is misaligned to both prominence cues (whereas in OVS, semantic role is only misaligned to grammatical role). In turn, children may accordingly use their early developed and robust NOUN-VERB-NOUN schema, and it is then no surprise that SVO-der resolves to the second mention for sentences containing dative object-experiencer verbs in the same way it was with active-accusative verbs. This offers a more fine-grained multiple-constraints perspective of children's understanding of ambiguous pronouns, and fits the previous argument by Arnold et al. (Reference Arnold, Brown-Schmidt and Trueswell2007, see Introduction) that children initially assign less weight to cues that are determined to be less reliable because of less consistent overall mappings in their CDS input.

Our above argument is speculative, but is built on similar proposals within the domain of language acquisition that are becoming uncontroversial, the core argument being that earlier developed schemas can impact the interpretation of sentences that can be defined as low frequency whether that frequency is assessed in terms of full constructions or more abstract forms (Ambridge et al., Reference Ambridge, Kidd, Rowland and Theakston2015; Abbot-Smith & Behrens, Reference Abbot-Smith and Behrens2006; Diessel & Tomasello, Reference Diessel and Tomasello2005; MacWhinney, Bates & Kliegl, Reference MacWhinney, Bates and Kliegl1984; Tomasello, Reference Tomasello2003). Further experimental work is needed with younger children to investigate whether they might be more likely to default to a simplistic order of mention cue relative to grammatical role or semantic role, and with older children to investigate the maturation of adult-like weightings of cues. For example, priming studies can explore whether greater exposure to dative object-experiencer verbs can raise the likelihood that their continuations focus on the proto-agent, which would suggest improved representations for their unique semantic mappings onto structural information, and in turn inform literature on implicit statistical learning mechanisms (Kidd, Reference Kidd2011).

From a broader cognitive perspective, our findings accommodate the notion that children build a situation model in the same way as adults (Pyykkönen & Järvikivi, Reference Pyykkönen and Järvikivi2012; Zwaan & Radvansky, Reference Zwaan and Radvansky1998). Specifically, they use prominence cues to form a representation of the most accessible entity that is likely to be involved in topic continuation. In regard to incrementally updating the situation model, it is worth noting that the non-prototypical mapping of semantic role onto the structural information of referents might increase processing demands for children (Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Brandt, Lieven and Tomasello2007; Noble et al., Reference Noble, Iqbal, Lieven and Theakston2015; Theakston, Coates & Holler, Reference Theakston, Coates and Holler2014, 2014). Indeed, developmental research has attributed young children's (around 3 to 6 years) less stable and slower pronoun resolution to a less certain processing availability (Hartshorne et al., Reference Hartshorne, Nappa and Snedeker2015; Järvikivi et al., Reference Järvikivi, Pyykkönen-Klauck, Schimke, Colonna and Hemforth2014). Such research posits that these factors may lead to difficulty in revising initial interpretations or in suppressing recent salient information, perhaps even a combination. Since a design like ours offers the opportunity to determine children's weighting of competing prominence cues, the incorporation of a comprehensive battery of individual difference measures such as working memory and language knowledge as predictors may lead to a more fine-grained understanding of how adult-like resolution preferences develop. Similarly, it is possible that age served as a proxy for developmental progression in academic ability. For example, future work could more specifically assess sentence comprehension ability to examine whether stronger skills are predictive (over and above age) of the likelihood that performance is more driven by semantic role.

Overall, the study has demonstrated that seven- to ten-year-olds attend to order of mention, grammatical role and semantic role cues in their real-time resolution of two pronoun forms er and der. The degree to which these cues were individually weighted was form-specific: for children to display robust interpretative preferences with er, order of mention cues needed to be aligned with both grammatical role and semantic role whereas only one of these alignments was required for der. Results also demonstrated that children's online comprehension of er and der became more adult-like with increasing age – specifically older children increasingly weighted semantic over grammatical cues.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (http://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/) Insight Grant (Understanding Children's Processing of Reference in Interaction, 435-2017-0692) to Juhani Järvikivi.

Appendix

Table A.1. Experiment 1 summary statistics for the complimentary Generalized additive mixed model process, using a set of binary predictors. Reporting parametric coefficients (Part A) and effective degrees of freedom (edf), reference degrees of freedom (Ref.df), F and p values for the smooth and random effects (Part B)

Table A.2. Experiment 2 summary statistics for the complimentary Generalized additive mixed model process, using a set of binary predictors. Reporting parametric coefficients (Part A) and effective degrees of freedom (edf), reference degrees of freedom (Ref.df), F and p values for the smooth and random effects (Part B)