Introduction

The production of referential expressions is a ubiquitous part of communication, and it requires pragmatic judgments about what is appropriate in a given context (Ariel, Reference Ariel1990, Reference Ariel, Sanders, Schliperoord and Spooren2001; Davies & Arnold, Reference Davies, Arnold, Cummins and Katsos2018; Serratrice & Allen, Reference Serratrice and Allen2015). For example, when talking about a dog, there are multiple semantically and morpho-syntactically acceptable options (e.g., a dog, the dog, Spotty, it/he/she, my old dog, my pet, this one,). The choice of linguistic expression is determined by its pragmatic relevance in a specific context. Referential expression use is difficult for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (e.g., Arnold, Bennetto & Diehl, Reference Arnold, Bennetto and Diehl2009; Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright & van der Lely, Reference Colle, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and van der Lely2008; Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou & Francis, Reference Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou and Francis2013; Malkin, Abbot-Smith & Williams, Reference Malkin, Abbot-Smith and Williams2018; Nadig, Vivanti & Ozonoff, Reference Nadig, Vivanti and Ozonoff2009; Norbury & Bishop, Reference Norbury and Bishop2003; Novogrodsky, Reference Novogrodsky2013; Novogrodsky & Edelson, Reference Novogrodsky and Edelson2016). However, little is known about how bilingual children with ASD use referential expressions (but see Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019; Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou & Tsimpli, Reference Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou and Tsimpli2020).

The current study was devised to assess the separate and combined effects of bilingualism and ASD on the use of referential expressions. It focused on two properties of referential choice: (1) informativeness, which is indexed by a contrastive use of referential expressions; and (2) the use of definiteness. These two properties were chosen as they presumably tap into language-universal (informativeness) and language-specific (definiteness) aspects of referential choice in typical and atypical language development. Some properties of referential choices are suggested to be more language-universal (e.g., the use of more informative nominal phrases for less accessible referents), while some properties are language-specific (e.g., the presence of definiteness/indefiniteness marking) (Ariel, Reference Ariel1990, Reference Ariel, Sanders, Schliperoord and Spooren2001; Guerriero, Oshima-Takane & Kuriyama, Reference Guerriero, Oshima-Takane and Kuriyama2006; Hickmann & Hendriks, Reference Hickmann and Hendriks1999; Mishina-Mori, Reference Mishina-Mori2012).

The current study employed a four-group design to investigate the use of referential expressions by comparing monolingual Hebrew-speaking and bilingual Russian–Hebrew-speaking children with and without ASD. It was hypothesized that informativeness of referential expressions would not be negatively affected by bilingualism, under the assumption that this principle of referential choice is more language-universal. However, encoding of definiteness is language-specific; thus, the marking of definiteness might be affected by cross-linguistic influence if the two languages encode definiteness differently (as is the case of the languages evaluated in the current study: Russian and Hebrew). From this perspective, Russian–Hebrew bilingualism offers a unique opportunity because it enables us to test language-universal and language-specific properties of referential choices. Russian and Hebrew vary in encoding definiteness. Hebrew marks definiteness with the article ha- but does not mark indefiniteness morphologically. Russian has neither definite nor indefinite morphological markers. This contrast is shown in (1a-c).

Furthermore, in Hebrew the feature of definiteness participates in syntactic processes, e.g., definiteness agreement (see (2a-b)), and the use of direct object marking et which is required only in front of definite nouns (see 3a-b) (for more detail, see Danon, Reference Danon2001).

To the best of our knowledge, only two recent studies investigated the separate and combined effects of bilingualism and ASD on referential choice (Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019; Peristeri et al., Reference Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou and Tsimpli2020). Peristeri et al. (Reference Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou and Tsimpli2020) employed a four-group design in which Greek-speaking monolinguals with and without ASD, aged 7-12 years, were compared to bilinguals with and without ASD who spoke a variety of languages (Albanian, Russian, Swedish, and German). With ambiguous pronouns, i.e., a violation of the informativeness principle of referential use, the authors reported a significant ASD-by-bilingualism interaction. The source of the interaction stemmed from a performance in bilingual children with ASD compared to their monolingual peers, whereas no differences were found between the two groups with typical language development. The bilingual children with ASD produced fewer inadequate, under-informative referential expressions as compared to their monolingual ASD peers. Meir and Novogrodsky (Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019) also investigated the use of pronouns in subject and object conditions using a four-group design to compare monolingual Hebrew-speaking children with and without ASD to bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children with and without ASD, all aged 4-9 years. The findings indicated a robust effect of ASD on pronoun use; yet found no effect of bilingualism and no interaction between bilingualism and ASD. Bilingual children were not different from their monolingual peers on the use of pronouns. Note that Russian and Hebrew are similar in the language-specific property of referential choice, i.e., the use of overt and null pronouns. The findings of these two studies are in accord with previous research on bilingual children with special needs, e.g., Developmental Language Disorders (DLD, previously referred to as Specific Language Impairment (SLI)) (e.g., Bird, Genesee & Verhoeven, Reference Bird, Genesee and Verhoeven2016; Blom & Boerma, Reference Blom and Boerma2017; Degani, Kreiser & Novogrodsky, Reference Degani, Kreiser and Novogrodsky2019; Meir, Reference Meir2017; Zebib, Tuller, Hamann, Abed Ibrahim & Prévost, Reference Zebib, Tuller, Hamann, Abed Ibrahim and Prévost2020). These studies found no detrimental effect of bilingualism on language development in children with developmental disorders. It should be noted that some monolingual and bilingual children with ASD, not all, might have a comorbid DLD, showing problems with structural language skills (for more detail, see Meir and Novogrodsky (Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020) and studies cited therein). The current study expands on previous findings by investigating the separate and combined effects of referential choice beyond the use of pronouns.

There are potential similarities and differences between the use of referential expressions in Russian and Hebrew. The next two subsections discuss the encoding of informativeness and definiteness and how they are affected by bilingualism and ASD, to highlight language-universal and language-specific properties of referential use.

Informativeness of referential expressions: A language-universal property

The informativeness of a communicative message has been traditionally linked to the listener-oriented cooperative conversational principles of the Gricean Maxim of Quantity (Grice, Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975). In Gricean terms, the speaker should provide the listener with as much information as necessary, but not more. For example, the expression a/the dog is informative in the context of a single dog, but under-informative in a context in which there are several dog-referents. Alternatively, in the context of a single dog-referent, a/the white dog is over-informative. Thus, it is plausible to suggest that informativeness of referential expressions is a more universal property that is not expected to be affected by bilingualism. However, there is robust literature suggesting that informativeness is affected by ASD (e.g., Marinis et al., Reference Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou and Francis2013).

Bilingualism and Informativeness

Several studies have demonstrated that the referential choices in narratives by bilingual children are similar to those made by their monolingual peers in both languages (Andreou, Knopp, Bongartz & Tsimpli, Reference Andreou, Knopp, Bongartz, Tsimpli, Roberts, McManus, Vanek and Trenkic2015; Fichman & Altman, Reference Fichman and Altman2019; Fichman, Walters, Melamed & Altman, Reference Fichman, Walters, Melamed and Altman2020; Topaj, Reference Topaj and Chini2010). Serratrice and De Cat (Reference Serratrice and De Cat2020) found that bilingual children aged 5-7 years were as knowledgeable about the choice of referential expressions as monolingual peers when their language proficiency in English was controlled for. In the same vein, Antoniou, Veenstra, Kissine, and Katsos (Reference Antoniou, Veenstra, Kissine and Katsos2020) investigated a wide range of pragmatic phenomena (relevance, scalar, contrastive, manner implicatures, novel metaphors and irony) beyond the principles of informativeness. They found that school-age French–Dutch bilingual and West–Flanders bilectal children performed on par with their Dutch-speaking monolingual peers, despite lower language proficiency. These results imply that at least some pragmatic principles are language-universal and are not affected by specific language properties. However, some studies suggested that bilingual children might be ‘over-explicit’ in their referential choices (Sorace, Reference Sorace2016), i.e., bilinguals tend to overuse overt pronouns in contexts in which monolinguals resort to null elements. This ‘over-explicitness’ has been linked to enhanced cognitive abilities in bilinguals, such as Theory of Mind skills (Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2018), and executive functioning (see Gunnerud, Ten Braak, Reikerås, Donolato & Melby-Lervåg, Reference Gunnerud, Ten Braak, Reikerås, Donolato and Melby-Lervåg2020; Ware, Kirkovski & Lum, Reference Ware, Kirkovski and Lum2020 for meta-analyses). Sorace (Reference Sorace2016) suggested that bilinguals might have a higher threshold for deciding which reduced form is under-informative. In contrast, a recent study investigated bilingual children acquiring Greek as their societal language. It reported over-informativeness and under-informativeness of referential expressions in referential use as related to the child’s language experience (Torregrossa, Andreou, Bongartz & Tsimpli, Reference Torregrossa, Andreou, Bongartz and Tsimpli2021). This finding might question the assumption of language-universality of referential expressions. More research is needed to shed light on informativeness of referential expressions in bilingual children.

ASD and Informativeness

In sharp contrast to monolingual and bilingual children with TLD, the use of referential expressions in monolingual children with ASD does not comply with the principles of informativeness. Children with ASD tend to use under-informative referential expressions in narrative tasks (e.g., the boy, he, instead of the big boy, the older brother), which impede the listener’s identification of the two characters in the story (Marinis et al., Reference Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou and Francis2013; Nadig et al., Reference Nadig, Vivanti and Ozonoff2009). Deficits in referential use among individuals with ASD have been linked to impaired Theory of Mind (see Baron-Cohen, Reference Baron-Cohen2000; Yirmiya, Erel, Shaked & Solomonica-Levi, Reference Yirmiya, Erel, Shaked and Solomonica-Levi1998 for a meta-analysis), Weak Central Coherence (Loukusa & Moilanen, Reference Loukusa and Moilanen2009; Norbury & Bishop, Reference Norbury and Bishop2003) and/or to broader impairments in executive functioning abilities (see Demetriou, Lampit, Quintana, Naismith, Song, Pye, Hickie & Guastella, Reference Demetriou, Lampit, Quintana, Naismith, Song, Pye, Hickie and Guastella2018 for a meta-analysis).

However, a recent study showed no differences between ASD and TLD peers on the use of referential contrastive expressions by means of relative clauses with 1 or 2 referents (e.g., 1 referent: The boy who is stroking the cow; 2 referents: The boy who is stroking the cow is now blue and the boy/DEM/Ø who is stroking the horse is now green) (Stegenwallner-Schütz & Adani, Reference Stegenwallner-Schütz and Adani2020).

To recap, previous research on the informativeness of referential expressions suggests that this property is language-universal, as it is not affected by bilingualism. The lack of a bilingualism effect can be explained by the comparable and/or even enhanced performance of bilinguals compared to monolinguals with TLD in Theory of Mind skills (see Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2018 for a meta-analysis) and in executive functioning (see Gunnerud et al., Reference Gunnerud, Ten Braak, Reikerås, Donolato and Melby-Lervåg2020; Ware et al., Reference Ware, Kirkovski and Lum2020 for meta-analyses). Alternatively, atypical language development might affect the informativeness of referential expressions. The deficit with informativeness in individuals with ASD has been linked to impaired Theory of Mind (Yirmiya et al., Reference Yirmiya, Erel, Shaked and Solomonica-Levi1998 for a meta-analysis), Weak Central Coherence (Loukusa & Moilanen, Reference Loukusa and Moilanen2009; Norbury & Bishop, Reference Norbury and Bishop2003) and/or to broader impairments in executive functioning (see Demetriou et al., Reference Demetriou, Lampit, Quintana, Naismith, Song, Pye, Hickie and Guastella2018 for a meta-analysis).

Definiteness marking of referential expressions: A language-specific property

The choice of referential expressions is also constrained by the linguistic discourse context in addition to informativeness requirements (e.g., Ariel, Reference Ariel1990, Reference Ariel, Sanders, Schliperoord and Spooren2001). The distinction between given and new information requires perspective-taking and has been used to explain linguistic choices such as the use of definite (e.g., the dog) vs. indefinite expressions (a dog). This property of referential choice is language-specific, as there are well-documented cross-linguistic differences with regard to definiteness marking.

Bilingualism and encoding of definiteness

Previous research confirms that bilinguals are less accurate than their monolingual peers are in the marking of definiteness (e.g., Hervé & Serratrice, Reference Hervé and Serratrice2018; Kupisch, Reference Kupisch2007; Kupisch & Bernardini, Reference Kupisch, Bernardini, Anderssen and Westergaard2007; Serratrice & De Cat, Reference Serratrice and De Cat2020); strengthening this language-specific aspect of referential use. Specifically, lower accuracy on definiteness marking has been linked to the effects of cross-linguistic influences, i.e., the influence of a second language that does not have an article system (e.g., Andreou, Peristeri & Tsimpli, Reference Andreou, Peristeri and Tsimpli2020; Chondrogianni, Marinis, Edwards & Blom, Reference Chondrogianni, Marinis, Edwards and Blom2015; Schwartz & Rovner, Reference Schwartz and Rovner2015; Zdorenko & Paradis, Reference Zdorenko and Paradis2012). For example, negative cross-linguistic influence has been demonstrated for the acquisition of definiteness in Hebrew for Russian–Hebrew speaking bilinguals. The Hebrew definite marker ha- is used by Hebrew-speaking monolinguals by the age of two years (Berman & Lustigman, Reference Berman, Lustigman, Ball, Crystal and Fletcher2012; Zur, Reference Zur1983), whereas Russian–Hebrew bilinguals acquiring Hebrew are less accurate with definiteness marking than their monolingual peers are (Armon-Lotem & Avram, Reference Armon-Lotem, Avram, Di Sciullo and Delmonte2005; Fichman et al., Reference Fichman, Walters, Melamed and Altman2020; Meir, Walters & Armon-Lotem, Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2017). These findings imply that definiteness marking is related to language-specific properties of the language pair that a bilingual child speaks.

ASD and encoding of definiteness

Turning to atypical language development, previous research points to deficits in encoding definiteness in individuals with ASD; yet, the specific findings conflict when applied to languages that have both definite and indefinite articles. Some studies showed that children with ASD introduce a story character inappropriately compared to their TLD peers, i.e., with a definite noun phrase (NP), rather than a required indefinite one (Norbury & Bishop, Reference Norbury and Bishop2003). Other studies have reported that children with ASD over-generate indefinite markers in contexts requiring the use of definite referents. For example, on an elicitation task, Dutch-speaking children with ASD showed similar performance on the indefinite conditions compared with TLD peers, yet they over-used indefinite articles instead of definite counterparts in contexts requiring a definite marker (e.g., Schaeffer, Reference Schaeffer2020; Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn & Creemers, Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and Creemers2018). The challenges with definiteness in children with ASD are not limited to languages that mark definite and indefinite contrasts morphologically. For example, in Mandarin (a language that encodes old/new information through a combination of nouns with demonstratives, numerals, or classifiers rather definite/indefinite articles), children with ASD had difficulties with encoding definiteness/indefinite contracts in comparison with their TLD peers (Sah, Reference Sah2018).

Previous findings call into question the extent to which definiteness is solely related to pragmatic skills. For example, article choice has been shown to be problematic in children with DLD/SLI (Blom, Vasić & Baker, Reference Blom, Vasić and Baker2015; Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2015; Chondrogianni et al., Reference Chondrogianni, Marinis, Edwards and Blom2015; Restrepo & Gutiérrez-Clellen, Reference Restrepo and Gutiérrez-Clellen2001; Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn & De Haan, Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and De Haan2014; Tsimpli & Stavrakaki, Reference Tsimpli and Stavrakaki1999; Tsimpli, Peristeri & Andreou, Reference Tsimpli, Peristeri and Andreou2017). Problems with definite/indefinite marking may be attributed to impaired acquisition of morpho-syntax in children with DLD/SLI, which is a core phenotype of these children (e.g., Blom et al., Reference Blom, Vasić and Baker2015). Thus, it is important to bear in mind that definiteness marking can be related to problems with acquiring morpho-syntax and problems with marking pragmatic aspects.

In summary, previous research involving bilingual children and previous research on children with DLD/SLI and ASD suggest that encoding definiteness is language-specific. This property of referential choice might be affected by lower morpho-syntactic skills in bilinguals as well as in monolinguals with ASD and DLD/SLI.

The current study

The current study assessed the separate and combined effects of language status and clinical status on the use of referential expressions by using a four-group design which compared monolinguals vs. bilinguals (language status) and ASD vs. TLD (clinical status: see Paradis, Reference Paradis2010) for a discussion on measuring separate and combined effects of language status and clinical status). Bilingual (Russian and Hebrew) children participated in the current study. Separate and combined effects of language status and clinical status were investigated for two properties of referential choice: (1) informativeness of referential expressions, which is indexed by the contrastive use of referential expressions, reflecting language-universal principles; and (2) use of the definite marker ha-, representing characteristics that are language-specific. Russian–Hebrew bilingualism offers a unique opportunity to contribute to our understanding of how language-universal and language-specific properties are affected by bilingualism and ASD. While Russian and Hebrew vary in the way they convey definiteness, the two languages presumably follow similar informativeness requirements.

Research Question 1: What are the separate and combined effects of language status and clinical status on the informativeness of referential expressions? We expected no negative effect of dual language exposure on informativeness, i.e., we predicted no difference in the use of contrastive referential expressions between monolinguals and bilinguals, as contrastive referential choice seems to be governed by language-universal principles. An alternative prediction was that bilinguals might show an informativeness advantage compared to their monolingual peers due to enhanced perspective-taking abilities (Schroeder, Reference Schroeder2018). Based on previous research, we predicted that children with ASD would be more likely to employ under-informative referential expressions as compared to their TLD peers. With respect to the combined effects of Bilingual Status and Clinical Status, we predicted no double deficit in bilingual children with ASD as compared to their monolingual peers with ASD in the use of contrastive referential expressions.

Research Question 2: What are the separate and combined effects of language status and clinical status on the definiteness marking of referential expressions? We predicted a negative effect of bilingualism on the use of definiteness for Russian–Hebrew speaking bilingual children with and without ASD. This prediction was informed by the negative cross-linguistic influence from Russian, which has no morphological marker for definiteness. In line with this prediction, we further expected bilinguals to have problems with syntactic properties of definiteness (i.e., definiteness agreement and the accusative marker et in front of definite NPs). Based on previous research, we hypothesized that Hebrew-speaking children with ASD (both monolingual and bilingual) would be more likely to use indefinite unmarked forms in definite contexts as compared to their peers with TLD (both monolingual and bilingual), with no interaction effects between these two factors.

Method

Participants

Ninety-two monolingual Hebrew and bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children with and without ASD participated (Mage=7;4 yr SD =1;3 yr; Range: 4;6-9;2 yr). Table 1 presents background information per child group. Bilingual children with and without ASD, born to Russian-speaking parents, were acquiring Russian as their heritage language in their home setting, from birth. Age of onset of Hebrew (the societal language in Israel) varied (Mage of onset of Hebrew=1;4 yr SD =1;8 yr; Range: 0-6;8 yr). All children in the current sample were raised in Israel in families with mid-high socio-economic status. The children were enrolled in mainstream and special education kindergartens and schools (Grades 1-2), where the language of instruction was Hebrew. In Israel, compulsory education starts at the age of 5 and children attend educational settings 6 days a week from 8 am till 1 pm (Novogrodsky & Kreiser, Reference Novogrodsky, Kreiser, Law, Murphy, McKean and Thordardottir2019).

Table 1. Background information on the participants

Note: ADOS-2 = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2, Lord et al., Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi, Gotham and Bishop2012); Non-verbal IQ = Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., Reference Raven, Court and Raven1998); LITMUS Hebrew SRep-30 = LITMUS Hebrew Sentence Repetition (Armon-Lotem & Meir, Reference Armon-Lotem and Meir2016; Meir et al., Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2016); LITMUS Russian SRep-30 = LITMUS Russian Sentence Repetition (Armon-Lotem & Meir, Reference Armon-Lotem and Meir2016; Meir et al., Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2016); LITMUS Hebrew CLT = LITMUS Hebrew Cross-linguistic Task (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017); LITMUS Russian CLT = LITMUS Russian Cross-linguistic Task (Gagarina & Nenonen, Reference Gagarina and Nenonen2017).

The participantsFootnote 5 were grouped according to their clinical and language status: 1) monoASD, Hebrew-monolinguals with ASD (n=21); 2) biASD, Russian–Hebrew bilinguals with ASD (n=14), 3) monoTLD, Hebrew-speaking monolinguals with TLD (n=28) and 4) biTLD, Russian–Hebrew bilinguals with TLD (n=30). In addition, 18 monolingual adult Hebrew speakers participated as controls. One bilingual child with ASD could not complete the tasks in Hebrew; thus, the data are reported for 13 children in the bilingual ASD group.

All children with ASD were diagnosed prior to the study and were recruited from special education classes and kindergartens. Formal ASD diagnosis in Israel follows the DSM-5 criteria and includes separate diagnoses from a psychologist and a physician (pediatric neurologist or psychiatrist) (Dinstein, Arazi, Golan, Koller, Elliott, Gozes, Shulman, Shifman, Raz, Davidovitch, Gev, Aran, Stolar, Ben-Itzchak, Snir, Israel-Yaacov, Bauminger-Zviely, Bonneh, Gal, Shamay-Tsoory, Zait, Hadad, Gross, Faroy, Bachmat, Eran, Uzefovsky, Flusser, Michaelovski, Levine, Kodesh, Gothelf, Marom, Feldman, Yosef, Bloch, Sadaka, Schtaierman, Davidovitch, Begin, Gabis, Zachor, Menashe, Golan & Meiri, Reference Dinstein, Arazi, Golan, Koller, Elliott, Gozes, Shulman, Shifman, Raz, Davidovitch, Gev, Aran, Stolar, Ben-Itzchak, Snir, Israel-Yaacov, Bauminger-Zviely, Bonneh, Gal, Shamay-Tsoory, Zait, Hadad, Gross, Faroy, Bachmat, Eran, Uzefovsky, Flusser, Michaelovski, Levine, Kodesh, Gothelf, Marom, Feldman, Yosef, Bloch, Sadaka, Schtaierman, Davidovitch, Begin, Gabis, Zachor, Menashe, Golan and Meiri2020). Diagnostic protocols vary across different clinics in Israel, with some clinics performing standardized ADOS and standardized cognitive and language assessments, while others rely more on clinical evaluations (Dinstein et al., Reference Dinstein, Arazi, Golan, Koller, Elliott, Gozes, Shulman, Shifman, Raz, Davidovitch, Gev, Aran, Stolar, Ben-Itzchak, Snir, Israel-Yaacov, Bauminger-Zviely, Bonneh, Gal, Shamay-Tsoory, Zait, Hadad, Gross, Faroy, Bachmat, Eran, Uzefovsky, Flusser, Michaelovski, Levine, Kodesh, Gothelf, Marom, Feldman, Yosef, Bloch, Sadaka, Schtaierman, Davidovitch, Begin, Gabis, Zachor, Menashe, Golan and Meiri2020). In this study, we reconfirmed the ASD diagnosis and obtained an index of ASD severity for individuals in the ASD group. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2: Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi, Gotham & Bishop, Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi, Gotham and Bishop2012) was administered to all children with ASD by a research assistant with a diploma in speech-and-language therapy who had been certified to conduct ADOS-2 assessment for research purposes. The monoASD and biASD groups did not differ in the severity of ASD as measured by ADOS scores (t(32)=.77, p=.45).

As shown in Table 1, the four groups (monoASD, biASD, monoTLD and biTLD) did not significantly differ with respect to chronological age (F(3,89)=.04, p=.99). All children were tested for non-verbal IQ using Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (Raven, Court & Raven, Reference Raven, Court and Raven1998). No significant difference was found between the groups for Raven scores (F(3,89)=1.12, p=.35). Morpho-syntax of all children was tested using a shortened version of the Hebrew and Russian LITMUS Sentence-Repetition task (SRep-30) (based on SRep-56 tasks, Armon-Lotem & Meir, Reference Armon-Lotem and Meir2016; Meir, Walters & Armon-Lotem, Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2016). The groups differed significantly in their morpho-syntactic abilities (F(3,88)=19.35, p<.001). A Tamhane T2 test for unequal variance showed the following group differences in the Hebrew SRep task: monoTLD > biTLD > monoASD=biASD. On the Russian SRep test, the biTLD group scored significantly higher that the biASD group (t(13.08)=3.00, p=.01) (these differences are discussed in detail in Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020). Additionally, the children’s receptive vocabulary was tested using noun and verb comprehension subtests of the Hebrew LITMUS CLT task (Altman, Goldstein & Armon-Lotem, Reference Altman, Goldstein and Armon-Lotem2017) and the Russian LITMUS CLT task (Gagarina & Nenonen, Reference Gagarina and Nenonen2017). In Hebrew, there was a gap between monoTLD and biTLD results. However, the monoASD and the biASD groups scored similarly: monoTLD > biTLD=biASD=monoASD (F(3,88)=8.45, p<.001). On the Russian CLT receptive task, there was no significant difference between the biASD and biTLD groups (t(13.80)=1.72, p=.11). The gap between TLD monolinguals and bilinguals for vocabulary knowledge was well-documented in previous research (for an overview, see Haman, Łuniewska & Pomiechowska, Reference Haman, Łuniewska, Pomiechowska, Armon-Lotem, Jong and Meir2015).

The Experimental Task: Referential Expression Use

The elicitation task developed for the current study was modelled after similar tasks tapping into referential choice (e.g., Armon-Lotem & Avram, Reference Armon-Lotem, Avram, Di Sciullo and Delmonte2005; Schaeffer, Hacohen & Bernstein, Reference Schaeffer, Hacohen, Bernstein and Falk2003; Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and Creemers2018). The task contained non-contrastive (Table 2) and contrastive (Tables 3a-b) conditions in subject and object positions. Non-contrastive indefinite conditions were intended to serve as the baseline for referential choice, while contrastive definite conditions were intended to shed light on informativeness of referential expressions, and marking of definiteness of referential expressions. The pictures for the stimuli were taken from educational websites (e.g., https://www.mycutegraphics.com/graphics/emotions/scared-girl.html) and clipart resources (e.g., http://clipart-library.com/mini-poodle-cliparts.html). The task is accessible via the IRIS Digital Repository.

Table 2. Stimuli for the Non-contrastive Indefinite Conditions (Subject and Object)

Table 3a. Stimuli for the contrastive definite subject condition

Note: Images were arranged in the right-to-left direction on the screen following the direction of the Hebrew script.

Table 3b. Stimuli for the contrastive definite object condition

Note: Images were arranged in the right-to-left direction on the screen following the direction of the Hebrew script.

The informativeness of referential expressions in the subject condition was evaluated by manipulating two referents that differed in one property only (e.g., a white dog and a black dog; see Table 3a). In object conditions, we manipulated two different objects and two different locations (see Table 3b). To ensure the use of definiteness, the referents in the subject and object conditions were introduced into a discourse; thus, in both subject and object syntactic conditions, anaphoric definiteness was mandatory. Note that these manipulations elicited syntactic properties of definiteness: a) mandatory definiteness agreement (e.g., ha-kelev ha-lavan ‘DEF-dog DEF-white’, Table 3a-b; b) the mandatory use of the direct object marker et in front of definite nouns (e.g., hi sama et ha-kova ba-kufsa ‘she put ACC DEF-hat into the box’, Table 3b) (Danon, Reference Danon2001). In the subject condition, the contrastive use of referents in the definite conditions required definiteness spreading; and in the object condition, it required the use of the accusative marker et. The task included five prompts per condition. There were two NPs per each stimulus in the definite subject (Table 3a) and the definite object (Table 3b) conditions, targeting the use of contrastive referential expressions.

Procedure

The study was approved by the IRB of The University of Haifa and the Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Education. The study is part of a larger project on bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children with ASD (Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020)Footnote 6. Adult participants provided written informed consent. For each child, parental written informed consent was obtained prior to participation. Before each testing session, the child’s oral assent was obtained. Each participant was individually tested in Hebrew in a quiet room at their preschool/school or home. The bilingual children were also tested in Russian by the first author, a native Russian speaker, during a separate meeting. Russian and Hebrew sessions for bilingual children were counter-balanced.

In the experimental task, participants were presented with a set of two static pictures on a computer screen. The participants were instructed to describe what was happening in the two pictures using the fixed prompts for each condition (Tables 2 and 3a-b). The duration of the task varied from 7 to 12 minutes. The participants’ responses were audio-recorded for further transcription and off-line coding.

Coding schema

First, in all conditions, we noted the type of referential expression used (see Tables 4 and 5). In contrastive conditions, it was noted whether the referential use was contrastive. This was coded as a binary YES/NO manner. Contrastive use of referential expressions was expected to shed light on the informativeness of referential expressions across the four child groups.

Table 4. Coding schemata for referential choices in the definite subject condition

Table 5. Coding schemata for referential choices in the definite object condition

Second, for each element produced we noted whether it was marked for definiteness using the marker ha- or not (ha-kelev ha-lavan ‘DEF-dog DEF-white’ vs. kelev lavan ‘dog white’; ha-kelev ‘DEF-dog’ vs. kelev ‘dog’. Note that in Hebrew, there is no indefinite marker). We noted whether both NPs were definite/indefinite or if the pattern was mixed (see Tables 4 and 5).

Finally, syntactic features of definiteness, such as definiteness agreement and the use of the accusative marker et in definite contexts, were also noted. For definiteness agreement, we noted whether the noun and the adjective were marked for definiteness by noting ungrammatical NPs with mixed definiteness marking patterns (e.g., *ha-kelev lavan ‘DEF-dog white’ or *kelev ha-lavan ‘dog DEF-white’). Furthermore, we noted ungrammatical responses in which the accusative marker et was used in front of indefinite objects (e.g., *hu sam et mexonit al ha-kise ‘he put ACC car.INDEF on the chair’) and responses with definite objects that lacked the accusative marker et (e.g., *hu sam _ ha-mexonit al ha-kise ‘he put _DEF-car on DEF-chair’, see Footnote 4 for more information about this type of response).

The rate of no-answer and unscorable responses was low across all groups for all the conditions (<.04 in each group), see Figures 2a and b for contrastive conditions.

Inter-rater reliability

Sixteen percent of the data (12 children: 6 with ASD and 6 with TLD) originally coded by a research assistant were re-coded by the first author to obtain indices of inter-rater reliability. The agreement rate between the two coders for referential choice varied from 90% to 100%, with an average agreement rate of 95.2% (ASD: 93.2%; TLD 95.3%). The agreement rate for the definiteness coding varied from 91% to 100%, with an average of 96.2% (ASD: 95.8%; TLD 96.6%).

Statistical Analysis

In order to compare performance across child groups with respect to the contrastive use of referents, we fitted a binomial mixed-effects logistic regression model with the dependent variable, Contrastive Response, coded as 1=contrastive of referents; 0=non-constructive. Similar to the analysis for the contrastive use, a binomial mixed-effects logistic regression model was fitted with the dependent variable, definiteness, coded as 1=definite; 0=indefinite/mixed. For both types of analyses, we used R (R Core Team, 2012) to perform a linear mixed effects analysis.

The models were built by adding the random and fixed variables in a step-by-step procedure, starting with an intercept-only model as a baseline. The null models included both by-subject random intercepts and by-stimulus random intercepts. With the inclusion of random slopes, the models failed to converge, and therefore random slopes were not included in the final models. The first fixed effects incorporated into the models were Clinical Status (TLD; ASD), Language Status (Mono; Bi), Condition (Subject; Object) and 2-way and 3-way interactions between these variables. The variables and/or the interactions of the variables were kept in the model only if they significantly improved the fit of the model and resulted in a reduced AIC-value. In the Results section, we report the minimally adequate models that performed significantly better than the intercept-only baseline model. We also set pair-wise post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjusted significance levels. Second, we included two additional variables, Age and Morpho-syntactic abilities in Hebrew (as indexed by Sentence Repetition scores in Hebrew), since the participants in the four groups showed considerable variability on these variables.

Results

Baseline non-contrastive indefinite referential choice

First, we analyzed the data for the non-contrastive indefinite conditions. These conditions were viewed as the baseline, which enabled us to assess the extent to which the children comprehended the task and responded adequately to the experimental prompts. In the non-contrastive subject condition, which required reference to two entities, all participants favored one of the two options: a plural noun (e.g., kovaim ‘hats’) or two adjectival phrases (kova adom ve-kova kaxol ‘a red hat and a blue hat’) (see Figure 1a). In all groups, a singular noun was used to refer to a singular referent in a non-contrastive context in the object condition (see Figure 1b).

Figure 1a. Response patterns in non-contrastive indefinite subject condition per group (2 referents)

Second, the results indicated that all participants used the unmarked target indefinite form in the non-contrastive conditions (see Table 6). Definiteness was coded as Definite (ha-kelev ha-shaxor ‘DEF-dog DEF-black)/Indefinite (kelev shaxor ‘dog black’) or Mixed (*kelev ha-shaxor ‘dog DEF-black’). A ceiling performance was observed in all groups: children used the unmarked indefinite form in both the subject and object position. The use of definite forms in indefinite contexts was negligible across all the groups.

Table 6. Indefiniteness in non-contrastive referential expression per group (means per group)

The fit of the baseline models for non-contrastive conditions was not improved by including predictor variables such Language Status, Clinical Status and their interactions with informativeness and definiteness as dependent variables. These results indicate that in non-contrastive indefinite conditions, all participants chose the target indefinite referential expression, regardless of their Language Status (monolingual vs. bilingual) or Clinical Status (ASD vs. TLD). Additionally, these results reflect an understanding of the task requirements in all groups.

To address the research questions of the study with respect to the separate and combined effects of Bilingualism and ASD on informativeness and definiteness, the participants’ responses for the subject and object conditions targeting the use of definite contrastive referential expressions were analyzed.

Informativeness of referential expressions in monolingual and bilingual children with and without ASD

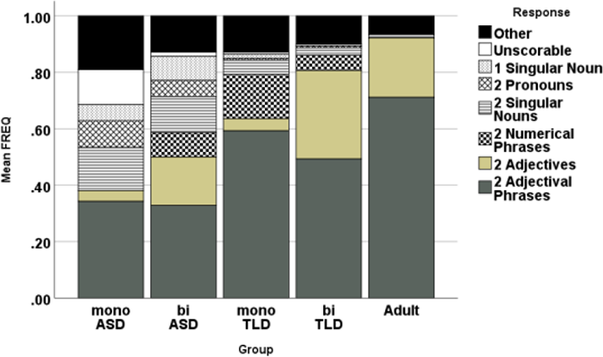

The first research question is related to the effects of bilingualism and ASD on the informativeness of referential expression. Participants’ responses are presented in Figures 2a and 2b. Two specific types of responses were frequently seen in the definite subject contrastive condition, as can be seen from both the adult data and the monolingual and bilingual TLD data: 2 adjectival phrases: ha-kelev ha-lavan/ha-kelev ha-shaxor ‘DEF-dog DEF-white/DEF-dog DEF-black’ and 2 adjectives (i.e., adjectival phrases with elliptical nouns: ha-lavan/ha-shaxor ‘DEF-white / DEF-black’). In the object condition, similarly to the adult group, the two TLD child groups (monolingual and bilingual) resorted to two singular nouns to contrastively refer to two different entities (e.g., ha-oto / ha-katar ‘DEF-car / DEF-locomotive’). The adult data (Figures 2a and 2b) confirmed our expectations with respect to the contrastive use of referential expressions in Hebrew. These patterns of responses were coded as contrastive, while other responses were coded as non-contrastive (1-contrastive, 0-non-contrastive).

Figure 2a. Response patterns in contrastive definite subject condition per group (2 referents)

Figure 2b. Response patterns in contrastive definite object condition per group (2 referents)

Note: Categories with frequencies of 0.05 were collapsed into ‘Other’

The performance on the contrastive use of referential expressions across the groups is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Contrastive referential expressions in the subject and object conditions per group

Responses coded as non-contrastive (1-contrastive, 0-non-contrastive) were analyzed using a binomial mixed-effects logistic regression model. Model 1 showed that Clinical Status and Syntactic Condition significantly contributed to the likelihood of informativeness of referential expression in children, but neither Language Status nor the interaction between Language Status and Clinical Status were significant predictors (see Table 7). Pair-wise post-hoc comparisons indicated that children with TLD were more likely to produce contrastive referential expressions compared to their ASD peers (estimate=2.26; S.E.=.44; Z=5.13, p<.001). Furthermore, regardless of their Clinical Status and Language Status, children were more likely to produce contrastive referential expressions in the object condition as opposed to the subject condition (estimate=1.52; S.E.=.28, Z=5.67, p<.001). In Model 2, we added Age and Morpho-syntactic skills (see Table 7). The results indicated that while Clinical Status and Syntactic Condition remained significant predictors of informativeness, Age was a significant predictor as well, indicating that children become more informative as they grow older. Interestingly, there was no effect of morpho-syntactic skills on the informativeness of referential expressions. Finally, according to both models, the interaction between Language Status and Clinical Status did not significantly predict informativeness of referential expressions.

Table 7. Parameters of the mixed effect models (Model 1 and Model 2) for informativeness of referential expressions. The odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values are given

In summary, the results for informativeness of referential expressions, as indexed by contrastive referential choice, indicated a negative effect of Clinical Status, meaning that children with ADS were less likely to encode referents contrastively. There was no effect of bilingualism on the informativeness of referential expressions, suggesting that bilingual children are not different from their monolingual peers in the choice of contrastive referential expressions. This is an interesting finding, as the bilingual children in the current sample scored lower on morpho-syntactic abilities in Hebrew as compared to their monolingual peers. Informativeness of referential expressions was significantly predicted by age: children were more likely to correctly encode referents contrastively as they grew older. In addition, all participants were more likely to choose contrastive referential expressions in the object condition as compared to the subject position. Finally, there was no interaction between Language Status and Clinical Status.

The use of definiteness in referential expressions in monolingual and bilingual children with and without ASD

To address our second research question, we focused on the use of the definite marker ha-. Table 8 presents descriptive statistics for the use of definiteness in referential expressions across the four child groups and the adult control group. Monolingual Hebrew-speaking adults showed a ceiling performance and consistently used the definite marker; thus, confirming our expectations for the use of ha- in definite contexts. However, the use of definiteness was not at ceiling across the child groups for the conditions targeting anaphoric definiteness in subject and object conditions, which contrasts sharply with the ceiling performance in the indefinite conditions (Table 6) across all the groups.

Table 8. The use of definite/indefinite and mixed forms in contrastive conditions (means per group)

The descriptive statistics for definiteness marking in the four child groups and in the adult control group are presented in Figure 4. Children with ASD marked referential expressions with the definite marker ha- less frequently compared to their TLD peers (ASD: M=.52; TLD: M=.80). Monolingual children were more accurate in using definite markers as compared to their bilingual peers (Mono: M=.75; Bi: M=.56). The definite marker ha- was used more frequently in the object condition as compared to the subject condition (Subject: M=.56; Object: M=.76).

Figure 4. Definiteness marking in contrastive referential expressions in the subject and object conditions per group.

Similar to the analysis of informativeness of referential expressions, we ran two models for the encoding of definiteness. Model 1 showed that Language Status, Clinical Status and Syntactic Condition were key predictors of the likelihood of definiteness marking (see Table 9). Pair-wise post-hoc comparisons indicated that children with TLD were more likely to encode definiteness as compared to their ASD peers (estimate=2.18; S.E.=.48; Z=4.53, p<.001) and monolingual children were more likely to produce the definite marker ha- as compared to their bilingual peers (estimate=1.33; S.E.=.47; Z=2.83, p=.004). Furthermore, children, regardless of their Language Status and Clinical Status, were more likely to mark definiteness in referential expressions in the object condition than in the subject condition (estimate=1.69; S.E.=.25, Z=6.81, p<.001). In Model 2, we added Age and Morpho-syntactic skills to the model (see Table 9). The results indicated that Syntactic Condition remained a significant predictor of definiteness use, yet Language Status and Clinical Status were no longer significant predictors. Unlike informativeness, which was predicted by Clinical Status and unaffected by morpho-syntactic skills, the use of definiteness in Hebrew was largely predicted by the child’s morpho-syntactic skills. Similar to informativeness, there was no significant interaction between Language Status and Clinical Status.

Table 9. Parameters of the mixed effect model for definiteness marking of referential expressions. The odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values are given.

Finally, we addressed the acquisition of syntactic properties of definiteness, i.e., definiteness agreement and the use of the accusative marker et in front of definite objects. Definiteness agreement can be evaluated only in adjectival phrases (a noun + its modifying adjective). Ungrammatical phrases with mixed marking patterns did not occur in indefinite conditions. However, there were cases of mixed patterns in the definite subject condition (e.g., *ha-kelev lavan ‘DEF-dog white’ or *kelev ha-lavan ‘dog DEF-white’) (monoASD: 6%; biASD: 2%, monoTLD: 2%; biTLD: 14%; Adults: 0%). These findings suggest that bilingual children are still in the process of acquiring definiteness properties in Hebrew.

Another syntactic property of definiteness in Hebrew is the use of an accusative marker in front of definite nouns in the object condition. The results indicated that there were no responses in which the accusative marker et was incorrectly used in front of indefinite direct objects (e.g., *he sama et sefer ba-tik ‘she put ACC book.INDEF in-the-bag’). Additionally, across all the groups the accusative marker et consistently co-occurred with the definite marker ha- in the object condition. In the same vein, the results showed no cases of the accusative marker et in responses of subject condition, supporting the claim that this syntactic property of definiteness is consistent in monolingual and bilingual children with and without ASD.

In the results for definiteness marking in referential expressions, lower morpho-syntactic abilities were determinants of inaccurate use of definiteness marking, i.e., overuse of unmarked indefinite forms. Morpho-syntactic abilities in Hebrew were found to be related to definiteness use, beyond and above Language Status and Clinical Status.

Discussion

The current study evaluated separate and combined effects of bilingualism and ASD on the use of referential expressions using a four-group design. We compared monolingual Hebrew-speaking and bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children with and without ASD. The study employed an elicitation task which tapped into the use of contrastive referential expressions and definiteness in Hebrew, aiming to shed light on the informativeness of referential expressions and the use of definiteness. Russian–Hebrew bilingualism was expected to advance our understanding on how exposure to two languages, which vary in how they encode definiteness, influences referential choice and definiteness marking in monolingual and bilingual children with and without ASD. We aimed to contribute to the existing literature regarding the extent to which informativeness of referential expressions is language-universal, while definiteness is language-specific, and to further understand how these properties of referential choice are affected by bilingualism and ASD.

We start with the combined effects of bilingualism and ASD, and then will discuss the separate effects of bilingualism and ASD on informativeness and definiteness. The combined effects of bilingualism and ASD did not show any double deficits for referential expressions in bilingual children with ASD, as seen by the lack of an interaction between language status and clinical status. This has been demonstrated for the aspects of informativeness and definiteness. These findings concur with previous studies that assessed the combined effects of bilingualism and ASD on language and cognitive skills (e.g., Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2017, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2019; Lund, Kohlmeier & Durán, Reference Lund, Kohlmeier and Durán2017; Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020; Paradis, Govindarajan & Hernandez, Reference Paradis, Govindarajan and Hernandez2018; Peristeri et al., Reference Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou and Tsimpli2020). Furthermore, the findings support previous research on bilingual children with DLD/SLI, Down Syndrome, Williams Syndrome, and hearing impairments (for a detailed overview, see Novogrodsky & Meir, Reference Novogrodsky, Meir and Schwartz2020 and the studies cited in it). The absence of an observed interaction between bilingualism and ASD has important clinical implications, as it suggests that there is no detrimental effect of bilingualism for children with ASD. The findings offer empirical evidence that children with ASD can be raised bilingually. In the next subsections, we discuss the separate effects of bilingualism and ASD on informativeness and definiteness marking.

Informativeness of referential expressions: effects of bilingualism and ASD

Our first research question addressed the separate and combined effects of bilingualism and ASD on the informativeness of referential expressions as indexed by the use of contrastive referential expressions. We hypothesized that informativeness of referential expressions is a language-universal property that is not compromised by dual language exposure, but it was expected to be affected by atypical language development. The results supported these predictions.

The findings indicated that informativeness of referential expressions is not affected by dual language exposure; yet, it is compromised in children with ASD. Starting with bilingual language acquisition, we found that bilingual children’s performance was on par with that of monolingual peers. Our results support previous research which showed that bilingualism does not negatively affect informativeness of referential expressions in bilingual children, despite lower proficiency in that language (Andreou et al., Reference Andreou, Knopp, Bongartz, Tsimpli, Roberts, McManus, Vanek and Trenkic2015; Fichman & Altman, Reference Fichman and Altman2019; Fichman et al., Reference Fichman, Walters, Melamed and Altman2020; Serratrice & De Cat, Reference Serratrice and De Cat2020; Topaj, Reference Topaj and Chini2010). This line of reasoning was also supported in a recent study which showed no differences between monolingual, bilingual and bi-dialectal children on measures of comprehension and processing of various factors with pragmatic meanings: relevance, scalar, contrastive, manner implicatures, novel metaphors and irony (Antoniou et al., Reference Antoniou, Veenstra, Kissine and Katsos2020). These findings, in addition to those from our study, suggest that informativeness of referential expressions is guided by language-universal principles, as had been previously suggested (Guerriero et al., Reference Guerriero, Oshima-Takane and Kuriyama2006; Hickmann & Hendriks, Reference Hickmann and Hendriks1999; Mishina-Mori, Reference Mishina-Mori2012). In the current study, bilingualism did not negatively affect informativeness of referential expressions, despite lower morpho-syntactic skills observed in bilingual children.

In contrast to children with TLD, children with ASD were more likely to produce under-informative responses. This was found under two conditions that required the contrastive use of referents: the subject condition requiring the modification of each referent (e.g., ha-kelev ha-lavan ve-ha-kelev ha-shaxor ‘DEF-dog DEF-white and-DEF-dog DEF-black’) and the object condition, requiring the use of two distinct referents/goals (e.g., hi sama et ha-sefer ba-tik ve-et ha-kova ba-kufsa ‘she puts DEF-book in +DEF-bag and-DEF-hat in+DEF-box’). The findings showed that the effect of ASD was robust regardless of language status, i.e., both monolingual and bilingual children with ASD were more likely to provide under-informative responses. These findings are in line with previous research that reported under-informativeness of referential expressions among individuals with ASD (Marinis et al., Reference Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou and Francis2013; Nadig et al., Reference Nadig, Vivanti and Ozonoff2009). However, the findings conflict with a study by Stegenwallner-Schütz and Adani (Reference Stegenwallner-Schütz and Adani2020) that found no TLD-ASD group differences for the use of contrastive referential expressions encoded via the use of a relative clause. This discrepancy suggests that the difficulty with informativeness among children with ASD is related to pragmatic difficulties in a communicative context rather than problems with morpho-syntax. This was supported by our analysis, which indicated that morpho-syntactic skills are not determinants of informativeness. In the study by Stegenwallner-Schütz and Adani (Reference Stegenwallner-Schütz and Adani2020), children were asked to answer direct questions promoting contrastive expressions, e.g., ‘Which boy is now blue and which boy is now green?’ In their responses, which were triggered by an explicit question, children specified and/or explicitly contrasted the number of referents matched between the color of the boy and one of the two NPs, e.g., a cow vs. a horse: ‘The boy who is stroking the cow is now blue and the boy who is stroking the horse is now green’. In the current study, as well as in the studies by Marinis et al. (Reference Marinis, Terzi, Kotsopoulou and Francis2013) and Nadig et al. (Reference Nadig, Vivanti and Ozonoff2009), the prompt was an open question, i.e., ‘What happened in the story?’ This prompt required a higher degree of integration between the child’s knowledge about the story, the listener’s knowledge, and the level of informativeness required.

In our study, children of all groups were more likely to use contrastive expressions in object condition as compared to subject condition. It is notable that in both conditions, the participants had to contrastively name two referents. In the subject condition, the two references were identical and varied only on one property; thus, requiring the use of a modifying adjective. Alternatively, in the object conditions, the participants could contrast the two referents with two different nouns and their different locations. Furthermore, the study showed that informativeness of referential expressions can be achieved via multiple linguistic phenomena. In the subject condition which prompted the adjectival modification, children preferred to resort to two different nouns: instead of ha-kelev ha-lavan / ha-kelev ha-shaxor ‘DEF-dog DEF-white/ DEF-dog DEF-black’, some children would use ha- kelev / ha-kalba ‘DEF.dog.MASC / DEF.dog.FEM’. Thus, future studies should manipulate the use of multiple contrastive linguistic devices: two nouns, nouns modified by adjectives and/or nouns modified by relative clauses.

To conclude, the results of this study demonstrated that while informativeness of referential expressions is not affected by bilingualism, it is affected by ASD. Additionally, informativeness of referential expression was related to age but not to children’s morpho-syntactic skills. As children grow, they learn to comply with informativeness principles. Theoretically, the findings of this study confirm that informativeness of referential expressions is a language-universal property. Clinically, we suggest that informativeness of referential expressions might be a potential clinical marker of pragmatic difficulties in both monolingual and bilingual children as it is not affected by dual language exposure and is not linked to morpho-syntactic skills.

Definiteness marking of referential expressions: effects of bilingualism and ASD

The making of definite vs. indefinite contracts is language-specific, as there are well-documented cross-linguistic differences. With this knowledge in mind, we investigated the use of definiteness in monolingual and bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children, since definiteness is encoded differently in Russian and Hebrew. This enabled us to investigate the extent to which language-specific aspects of referential expression use are affected by bilingualism and ASD. The results showed that definiteness marking was negatively affected by bilingualism and ASD due to lower morpho-syntactic skills in these children.

The findings suggest that children with ASD were more likely to produce unmarked indefinite referential expressions in contexts that required the use of a definite marker. Notably, there was no over-use of definiteness in the indefinite contexts. Bilingual children with TLD who speak Russian as their heritage language were found to be more likely to omit the definite marker ha- in discourse contexts requiring the use of ha- as compared to their monolingual Hebrew-speaking peers. Omissions of the definite marker ha- in Hebrew by bilingual Russian–Hebrew speaking children can be attributed to the properties of the Russian language, which has no morphological marker of definiteness. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that Russian–Hebrew bilinguals have problems with the acquisition of ha- (Armon-Lotem & Avram, Reference Armon-Lotem, Avram, Di Sciullo and Delmonte2005; Meir et al., Reference Meir, Walters and Armon-Lotem2017; Schwartz & Rovner, Reference Schwartz and Rovner2015). Similarly, previous research has demonstrated that bilingual children’s use of articles is susceptible to cross-linguistic influence, i.e., the influence of a language that does not use a definite-indefinite morphological marker on the other language (e.g., Chondrogianni et al., Reference Chondrogianni, Marinis, Edwards and Blom2015; Zdorenko & Paradis, Reference Zdorenko and Paradis2012). Thus, problems with definiteness marking in bilingual children cannot be taken as a sign of ‘immature/impaired pragmatics,’ rather these problems can be attributed to morpho-syntactic gaps between the two languages a bilingual child speaks. Our study confirmed this proposal, as the effect of bilingualism disappeared once morpho-syntactic skills were integrated into the model, suggesting that lower performance on definiteness marking was largely driven by lower morpho-syntactic skills.

Turning to the effect of ASD, our findings support previous research which showed that children with ASD have difficulties conveying definiteness (e.g., Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and De Haan2014; Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and Creemers2018). Previous studies investigated definiteness in children with and without ASD in languages that have distinct markers for encoding definiteness vs. indefiniteness (e.g., a dog vs. the dog in English, de giraffe vs. een giraffe in Dutch) (Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and De Haan2014; Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and Creemers2018; Tager-Flusberg, Reference Tager-Flusberg1995), and in languages with no morphological marker of definiteness, such as Mandarin (Sah, Reference Sah2018). In these studies, atypical definiteness vs. indefiniteness encoding was linked to ‘immature Theory of Mind, immature pragmatics, and weak verbal working memory’ (Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and Creemers2018, p. 91). Our findings indicate that problems with definiteness in Hebrew might be syntactic rather than pragmatic. This line of argumentation may also be supported by previous research which demonstrated that problems with definiteness are not unique to children with ASD. For example, children with DLD/SLI, whose linguistic phenotype includes morpho-syntactic difficulties, were also reported to show difficulties with definiteness marking (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Vasić and Baker2015; Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2015; Chondrogianni et al., Reference Chondrogianni, Marinis, Edwards and Blom2015; Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Van Witteloostuijn and De Haan2014; Tsimpli & Stavrakaki, Reference Tsimpli and Stavrakaki1999; Tsimpli et al., Reference Tsimpli, Peristeri and Andreou2017).

However, contrary to our expectations, all children in our study showed knowledge of core syntactic properties of definiteness, i.e., definiteness agreement and co-occurrence of the accusative marker et with definite nouns. We found no ungrammatical responses where the accusative marker et appeared in front of indefinite nouns, or where a definite noun in object condition appeared without the accusative marker. The absence of ungrammatical responses was surprising, as we know that some children with ASD in the sample had a comorbid morpho-syntactic language impairment (Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2019, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020). Our original hypothesis was that some children with ASD might have problems with syntactic properties of definiteness. This hypothesis was not confirmed. One possible explanation could be that the accusative marker et is the only accusative marker in Hebrew (Berman & Lustigman, Reference Berman, Lustigman, Ball, Crystal and Fletcher2012). It frequently co-occurs with ha- and is frequently pronounced as eta (et+ ha-) in spoken language, suggesting that the accusative marker and the definite marker are learned as one chunk. Future studies should investigate whether definiteness agreement and/or the use of the accusative marker pose problems to Hebrew speaking children with DLD/SLI as compared to children with ASD.

To conclude, the results of this study demonstrated that the encoding of definiteness is compromised in monolingual children with ASD and in bilingual children with and without ASD due to their lower morpho-syntactic skills. Among bilingual children this is due to reduced language exposure and among children with ASD, to language deficits. Thus, the findings of the study confirm that definiteness encoding is a more language-specific property.

Conclusions and Future Research

The current study showed that bilingualism does not affect informativeness of referential expressions despite lower language proficiency in bilingual children compared to their monolingual peers. Yet, informativeness of referential expressions is affected by ASD. With respect to definiteness encoding, it is negatively affected by both bilingualism and ASD. Importantly, informativeness of referential expression use was not influenced by morpho-syntactic skills, while definiteness was largely predicted by it.

This study adds to the existing literature which suggests that children with ASD can be raised bilingually, and that bilingualism does not impose an additional burden. As for the evaluation of language skills in monolingual and bilingual children with and without ASD, our study shows that some aspects of referential choice are more language-universal while others are more language-specific. Language-specific properties of referential choice (e.g., definiteness marking) should not be held as signs of pragmatic difficulties in bilingual children. In contrast, other more language-universal measures (i.e., informativeness) might provide more reliable insights into pragmatic skills of monolingual and bilingual children.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their most constructive comments, which helped us improve the manuscript. We would also like to thank the members of the Language Abilities in Children with Autism ‘LACA’ network (http://laca.humanities.uva.nl/wp/) for their ideas and discussions which inspired us to conduct this study. The authors are wholeheartedly grateful to the families and children who took part in the study, and to Marissa Hartston and Revital Berlowitz who helped with data collection. We also would like to thank Lexi Tuch for the proofreading of the earlier version of the manuscript. This research was partially supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1068/16) awarded to Rama Novogrodsky.