The Chanyuan Peace and a Chanyuan-Style War

In mid-January of 1005, Emperors Zhenzong of the Song (r. 998–1022) and Shengzong of the Khitan Liao (r. 982–1031) exchanged oath letters (誓書) that ended twenty-five years of war over the so-called Sixteen Prefectures, a strategic swath of land spanning the modern cities of Beijing to Datong that had come under Khitan control in 937. The resulting Chanyuan Covenant (澶淵之盟) ushered the still-young Song dynasty out of its period of military conquest and consolidation and into an era of extraordinary cultural and economic development. For the wartime leader Li Gang 李綱 (1083–1140), writing around 1126, after Song violation of the covenant had precipitated its own conquest by the Jurchen Jin, the treaty “forged by our court with the Khitan was abided by in trust and held together by beneficence. For over one-hundred years the border was at peace and military arms lay unused. Never before had there been such genuine reconciliation.”Footnote 1

Though meant solely as a bilateral treaty, the impact of the Chanyuan covenant extended well beyond relations between Song and Liao.Footnote 2 In recent years, historians have traced the origins of the treaty—and especially its radical acknowledgment that there could be multiple legitimate emperors in the world at one time—to the Khitan imposition of a “Liao world order” during the Five Dynasties. And they have seen in the Chanyuan agreements the foundation of a multistate order in East Eurasia—variously called the “Chanyuan system” (by Sugiyama Masaaki) or the “Chanyuan Treaty System” (by Furumatsu Takashi)—that was inherited by the Southern Song and Jin and endured until the Mongol conquests reestablished the rule of a unitary emperor.Footnote 3

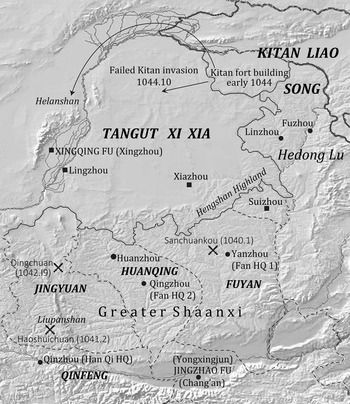

As I explain in greater detail below, my own concern is with the Chanyuan covenant as the embodiment of a war-averse approach to both frontier relations and the domestic political order. The geographic center of my study is the long borderland dividing the Song's Shaanxi region from the Tangut Xi Xia to the north and the Tibetan Tsongkha federation to the west (see Figure 1). Temporally, my focus is on the two decades separating the end of the first, defense-oriented Sino-Tangut (or Qingli) war of 1040 to 1044Footnote 4 and the inception of a half-century cycle of expansionist wars spanning 1068 to the disastrous attempt to recapture the Sixteen Prefectures in 1122. By the end of this cycle not only had the Song court abandoned the Chanyuan spirit of accommodation, it had explicitly renounced the original Chanyuan treaty with Liao. Received tradition ascribes that abandonment of the Chanyuan model to the irredentist ambitions of the Shenzong emperor (r. 1068–1085), as manipulated by his chief councilor Wang Anshi 王安石 (1021–1086) and embraced as a sacred legacy by his two sons, Zhezong (r. 1086–1100) and Huizong (r. 1101–1125). But I hope to show that even before Shenzong's ascent, commitment to the Chanyuan paradigm had been eroded by growing frustration at key levels of the Song state over how to manage the unpredictable actions of the Tanguts and the ominous disintegration of the Tsongkha federation. In short, the expansionist wars of Shenzong and his sons can be traced directly to the fragility of the Qingli peace.

Figure 1. Northern Song and its Neighbors

The specific terms of the Chanyuan covenant obliged the Song to forgo irredentist designs on the Sixteen Prefectures and required them to submit annual payments of one-hundred thousand ounces of silver and two-hundred thousand bolts of silk to the Khitan in return for the Liao's own cessation of claims to two “Guannan” (South of the Pass) prefectures (Yingzhou and Mozhou) lost to the Later Zhou in 959. In addition, the treaty prohibited the construction of new defense works on either side of the officially demarcated border, and established diplomatic parity between Song and Liao and their mutually recognized “sons of Heaven.”Footnote 5 From the perspective of the domestic Song political order, the Chanyuan treaty can be seen as the culmination of a growing literati fatigue with war in the decades leading up to 1005.Footnote 6 In the eyes of courtiers eager to bring the military phase of the dynastic founding to an end, the Chanyuan exchange of wealth, territory, and pride in return for peace along the northern frontier finally enabled the court and its literati servitors to reclaim sovereignty over a military class that had dominated the succession of northern dynasties and the chessboard of southern kingdoms in the aftermath of the Tang collapse.Footnote 7

The changes precipitated by the Chanyuan agreement crystallized around what I have previously termed the “Chanyuan paradigm,” whose key elements may be summarized as follows:Footnote 8 In foreign affairs, acknowledge the territorial sovereignty of your neighbors, concede diplomatic parity to your military equal, forgo territorial aspirations, and exchange Chinese wealth for border stability. In military affairs, maintain the loyalty of the Song officer corps with generous sinecures and lenient appointment privileges for their sons, while disregarding their policy advice and barring them from influential positions—including the top military positions—at either court or in the field. And in cultural matters, heighten the stress on civic culture by suppressing the power and allure of local paramilitary leaders, prohibiting private martial arts societies, and even banning the publication of military classics, all in an effort to replace a culture of arms with the love of books.

The Chanyuan demilitarizationFootnote 9 established a stable allocation of status, wealth, territory, and military prerogatives between two relatively equal parties as a dependable alternative to war. For both Song and Liao strategists the war-averse Chanyuan model constituted an acceptable and static status quo, but it also tempted Song policymakers to look the other way as the Tanguts, previously minor players on the international stage, acquired the territory, institutional apparatus, and military power of a major state. In the retrospective view of the reformer and future grand councilor Fu Bi 富弼 (1004–1083), although Chanyuan bought nearly forty years of peace, “After the great ministers of the realm all advocated rapprochement military preparations declined. Diligent frontier officials [who called for military preparations] were said to stir up trouble. . . and the mention of war became taboo. [Everyone at court was] contentedly self-absorbed, with no one worrying.”Footnote 10 For the censor Jia Changchao 賈昌朝 (997–1065), this self-absorption allowed both the Khitan and the Tanguts to assert ever-greater control over the steppe: “The various nations of the north [北方諸國] declare fealty to the Khitan while the various nations to the west declare loyalty to [the Tanguts]; West and North have combined to squeeze the Middle Kingdom.”Footnote 11

As a consequence of the Chanyuan demilitarization, when in the first month of 1040 Tangut forces under their state-building leader Weiming Yuanhao 嵬名元昊 (1003–1048, r. 1038–1048) exploded across the southern Ordos border between Xia and Shaanxi they made short work of a Song army clad in inferior armor and unable to load their crossbows, led by incompetent and untested officers chosen through nepotism rather than merit, answering to civilian leaders paralyzed by fright (see Figure 2). Not only did Song forces lose every major battle in the five-year Qingli war from 1040.1 to 1044.12, their humiliating performance tempted the Khitan to challenge the Chanyuan accords by demanding the return of the ten Guannan counties they had yielded in the original agreement.Footnote 12

Figure 2. The Sino-Tangut Warzone, 1040–1044.

● Song prefectures, selected

■ Xi Xia prefectures, selected

Major battle sites

Major battle sites

FUYAN, HUANQING, JINGYUAN, QINFENG: Shaanxi's four military circuits

But if the Chanyuan agreement had lulled the court into disregarding basic military preparations, the Chanyuan paradigm ultimately provided a model for regaining the strategic edge, by vesting defense against the Tanguts in the hands of literati practitioners of the civilian arts of good governance, especially the reform beacon Fan Zhongyan 范仲淹 (989–1052) and his young patrician associate Han Qi 韓琦 (1008–1075).Footnote 13 As the principal war strategists and lead military pacification commissioners (經略安撫使) in Shaanxi, Fan and Han assembled a cadre of reformist civilian lieutenants to survey the defensive weaknesses of the vast warzone, restore order in its shell-shocked prefectures and counties, embark on a major fort-building project, and mobilize local Han and Native (Fan 蕃) troops to serve under newly recruited commanders answerable to their civilian superiors.

For their emperor Renzong (r. 1022–1063), the sole objective of war was peace, and to that end he even entrusted Fan and his activist contingent (including Ouyang Xiu and Fu Bi) to institute a major reform program the premier goal of which, for the emperor, was to hasten war's end. Thus when by 1043 Song defensive successes impelled Yuanhao to seek rapprochement Renzong was eager to comply, despite Yuanhao's attempt to “usurp an imperial title” (僭號) that would make him the equal of the Song and Khitan rulers. From the field, Fan and Han insisted that, unlike the Khitan, Yuanhao had not earned imperial status; and they insisted that he be denied the imperial designation, lest as the so-called “Western Emperor” he come to serve as a lightning-rod for any miscreants caring to flee the Song. This Renzong could accept. But the ultimate goal, for Fan and Han, was to recover the Ordos lands from the Hengshan highlands in the east to Yuanhao's core domain of Lingzhou in the west, and this Renzong rejected.Footnote 14 For Renzong never ceased to view the war through a Chanyuan lens. Thus in late 1044 he accepted Yuanhao's vow of fealty, in return for which he enfeoffed Yuanhao as “King of the Western Xia,” conferred on him and his descendants perpetual rights to the Xi Xia lands they already possessed in return for his contrition, and granted him annual payments of some 250,000 units of silk, silver, and tea, along with permission to open two official trade markets on the border.Footnote 15 And not only did Renzong reject the continuation of war as a policy tool, he rejected the pro-war reformers Fan Zhongyan, Han Qi, and their coalition as policy makers: by 1045 every one of the pro-war reformers had been expelled from the capital and their reform measures aborted.Footnote 16 Though not quite at imperial status, Yuanhao had muscled his way into the “Chanyuan system,” and Renzong had restored a Chanyuan-style peace.

The Fragility of Peace

Why didn't peace with the Tanguts last? In the view of anti-war partisans in the aftermath of Shenzong's reign (1068–1085), peace did endure in the decades following Renzong's extension of the Chanyuan system, until decades of Tangut submissiveness were disrupted on Shenzong's ascent by merit-seeking opportunists, and by Wang Anshi's manipulation of the young emperor's desire to avenge the humiliating loss of the Sixteen Prefectures in order to abet his own reform vision.Footnote 17 But the notion that the post-Qingli decades were peaceful was in fact a delusion. As I hope to show, the static Chanyuan model based on compliance by two equally matched participants was shaken by the expansion to new actors with unmet political aims and varying levels of internal stability. Thus within a few years of the 1044 agreement, a complicated set of external shifts had been set in motion that challenged Song reliance on accommodation and forbearance as its main approach to managing the border, inclining courtiers and even Renzong's successor towards more muscular options well before Shenzong's enthronement.

To a significant extent, dissatisfaction with peace began at home. If the year 1044 saw the end of both a disastrous war and a disruptive attempt at reform, none of the underlying causes of either war or reform had been resolved. Perhaps most disappointingly, the end of the Qingli war brought no economic peace dividend. Instead, Tangut victories over both the Song and their erstwhile patrons the Khitan Liao confirmed the status of the Xia state as a major military power, obliging Song policymakers to maintain their huge if unreliable standing armies in the north.Footnote 18 This in turn required the Song state to dig ever more deeply into the commercial and agrarian economies, and to yoke the monopolized tea and salt industries to the imperatives of provisioning the distant and resource-poor northern frontier.Footnote 19 The bloated but inefficient Song war machine had always consumed the major part of the government's income, but by 1065 the roughly 1.2 million salaried troops drained some 50 million of the government's income of 60 million strings of cash, while the government registered its first overall financial deficit.Footnote 20

The post-Qingli fiscal problems were exacerbated by political instability along the northwestern frontier that the 1044 peace agreement had done little to quell (see Figure 3). Trouble within the family of the long-time Song ally and Tsongkha federation ruler Jiaosiluo 唃廝羅 (997–1065), lodged in Qingtang, was especially concerning. Qingtang (modern Xining, Qinghai Province) and its surrounding valleys east of Lake Kokonor (or Qinghai), in the region known by the Chinese as Hehuang 河湟, had come under Chinese suzerainty from the Han to the Tang, but was lost in the mid-eighth century to local tribes and outliers from the Lhasa-based Tibetan empire in the turmoil of An Lushan's rebellion. Throughout the late-tenth century rival factions of Tufan 吐蕃 Tibetans and Tanguts strenuously competed for control of Hehuang, as well as Liangzhou 涼 州 (modern Wuwei) and the oasis towns strung along the Gansu Corridor to the north. Jiaosiluo, imported from Gaochang by Huangshui Valley potentates because of his charisma as the putative last descendant of the Tufan royal line, made adroit use of the Song need for a counterweight against Tangut victory in the Gansu Corridor to emerge as master of the Hehuang region and principal supplier of war horses to the Song. By the mid-1030s Jiaosiluo had not only become a staunch military ally of the Song, he had also become immensely wealthy through his monopoly control over the Central Asian trade—especially in horses—that had to skirt south of the Tanguts through Qingtang in order to enter Song China. Although Jiaosiluo's political base was centered on Qingtang and the other towns (particularly Zongge and Miaochuan) of the Huangshui Valley, his influence radiated south to the satellite towns of the Yellow River Valley (referred to as Henan 河 南 by Song strategists); and southeast to the so-called Tao-He region (洮 河 間) bounded by Hezhou, on the Da Xia River, and Xi 熙, Min 岷, and Tao 洮 prefectures on the Tao River. The region east of Tao-He (the westernmost border of Shaanxi until Wang Shao's expansionist campaigns of 1068 on) was occupied by “cooked” (熟)—that is, compliant and registered—Tibetan tribes who clustered around Guwei Stockade and were the object of competitive “clientalization” (招納) by both the Song and the Xia.Footnote 21

Figure 3. The Northwest Front, Mid-eleventh Century

Jiaosiluo sowed the seeds of future trouble for his state when he banished his first wife and disinherited the two sons she bore him in favor of Dongzhan 董氊 (d. 1086), his son by a second woman. From the 1040s on, resentment prompted the ousted sons to establish break-away regimes in the Tao-He region that provided fertile opportunities for recruitment by the Tanguts, who combined a policy of attacking Jiaosiluo in Qingtang with courting his aggrieved kinsmen closer to the Song border. When Dongzhan succeeded Jiaosiluo in 1065 Muzheng 木征 (d. 1077), a rebel grandson in control of Hezhou, began to openly defy both Qingtang and the Song by submitting with his town to the Tanguts. By the end of the decade border unrest had begun choking off the crucial horse trade, as skittish military commanders blocked Tibetan horse caravans coming into the Song even as Tibetan horse traders slowed down their caravans in fear of bandit raids.Footnote 22

In addition to anxiously watching the political fragmentation of their principal ally, Song policymakers also had to adjust to the bloody strife agitating the ruling elite of their most dangerous foe. Internal Tangut politics in the post-Qingli era was dominated by lethal competition for power between the Weiming royal family and their successive consort clans.Footnote 23 In 1046, Weiming Yuanhao had his Yeli empress's brothers Yuqi and Wanrong killed, then took Yuqi's wife, Lady Mocang 沒藏, as his concubine. When in 1048 Yuanhao's Yeli-borne son got revenge by killing his father, Lady Mocang's brother Epang 訛龐 engineered the succession of her one-year old son Liangzuo 諒祚 (r. 1049–1067) under a Mocang regency dominated by Epang himself. But because Lady (now Empress Dowager) Mocang opposed her brother's efforts to wrest from Song control the Quye River region of Linzhou 麟州 in northwestern Hedong Circuit, Epang had her killed in 1056 and the 9-year-old Liangzuo made his son-in-law.Footnote 24 Revenge came full circle in 1061, when Liangzuo (now 15) allied with the powerful Liang family to murder Epang and eradicate the entire Mocang clan (including his Mocang wife), whom he replaced with his benefactress Lady Liang as his new wife and her brother Liang Yimai 梁乙埋 as his head of government. On Liangzuo's sudden death in 1067 he was succeeded by Lady Liang's 6-year old son Bingchang 秉常 (r. 1068–1086), putting the Weiming throne under Liang control until a coup and the death of a Liang dowager regent allowed the Weimings to regain power in the late 1090s.

Like a ship at sea, the post-Qingli Song state was ineluctably drawn into the maelstrom created by the political dramas playing out along the Shaanxi borderlands. From the perspective of the bilateral relations between Song and Xia, the two decades following 1044 evolved from an uneasy peace, to increasing border incursions largely provoked by the Xia, to an undeclared—and initially unauthorized—war launched in 1067 when the minor Song border general Chong E 种諤 (1027–1083) seized the Tangut town of Suizhou 綏州. An event of great controversy at the time, the Suizhou affair encapsulated larger Song debates about the significance of the Qingli war and the distinctions between wars of necessity and wars of choice. And because the Suizhou seizure was embraced by Shenzong as one of his first acts as emperor, it served as the opening salvo in his repudiation of the Chanyuan paradigm in favor of expansionist wars of choice. But as we will see, by the time of Shenzong's ascent the Chanyuan commitment had already been eroded by decades of border strife.

The End of Forbearance

Following the Qingli settlement of 1044/12, the prevailing Song attitude towards the Tanguts was one of forbearance, as Renzong and his chief ministers tamped down any actions that could be seen as provocative. This was easy in the five years following Yuanhao's assassination in 1048, when the Xia regime under Mocang Epang was preoccupied by war with the Khitan.Footnote 25 But with the restoration of peace in 1053 Epang was free to pursue his goal of wresting from Song control the prime farming lands along the Quye River 屈野河 flowing southwest through Hedong's Linzhou, a region impoverished by government grain requisitions, transport corvee, and the Tangut depredations. When in 1057 the Bingzhou Prefect and Hedong Military-Pacification Commissioner, Pang Ji 龐籍 (988–1063), followed the advice of his protégé and assistant Sima Guang 司馬光 (1019–1086) to immediately construct two forts to protect the farmers, he was accused by some in Renzong's court of “provoking a border crisis by arbitrarily building fortifications.”Footnote 26

The borders around Quye were finally settled in 1061, after Liangzuo's eradication of the Mocang clan prompted him and his new chief councilor, Liang Yimai, to proffer peace overtures towards the Song.Footnote 27 Such oscillation between aggression and accommodation fed into Song hopes that, despite their many transgressions, the Xia regime would adhere to its ritual status as a subject state. Thus while Song policymakers were willing to shut down border markets as a way to sanction Tangut offenses, they eschewed more combative responses.Footnote 28 In 1055, for example, Renzong ordered that a would-be defector, the Suizhou Tibetan chieftain A-ke-a 阿克阿 (or A'e 阿訛), be returned with his two-hundred followers to their Xia overlords, on the grounds that “Liangzuo is still young and pliable, so we do not wish to create a border affair.”Footnote 29

On Renzong's death in the third lunar month of 1063, his policy of forbearance was initially adopted by his cousin and successor Yingzong (r. 1063.4–1067.1). In 1064.9, the former assisting state councilor and current Military-Pacification Commissioner of Shaanxi's Fuyan Circuit, Cheng Kan 程勘 (990–1066), reported that a group of Hengshan tribal chieftains had come to Yanzhou to seek Song military assistance in their plan to rebel against the repressive Liangzuo and seize the southern Ordos prefectures for themselves. In Cheng Kan's view, “Liangzuo has long been contrary and disrespectful, so it would be appropriate to seize this opportunity and aid [the Tibetans], thereby using barbarians to attack barbarians; in this case the Middle Kingdom will benefit.” As with earlier calls to action, Cheng's memorial elicited the emperor's displeasure and dismissiveness from senior ministers wary of “causing trouble” (生事).Footnote 30 But shortly thereafter Liangzuo pushed beyond what even the accommodationist Song court could accept, when in late Autumn of 1064 he sent a force estimated at 200,000 men against clientalized Tibetan tribes and frontier outposts around Qinzhou and Weizhou, “raping and pillaging and burning for hundreds of li, until everything had been wiped out.”Footnote 31 The Tangut assault provided a turning point, or what chief councilor Han Qi called “this moment of opportunity” (此得機會矣) to build on the lessons of the Qingli war with Yuanhao to reshape Song responses to Yuanhao's son Liangzuo.Footnote 32

Debating the Lessons of Qingli

Ouyang Xiu

Han was aided in that campaign to learn from Qingli by his old reform comrade and current colleague on the state council, Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007–1072).Footnote 33 Ouyang Xiu had bucked the desires of Renzong in early 1044 by vigorously opposing what he saw as a premature peace with Yuanhao.Footnote 34 Now, twenty years later, in 1064, he feared that the court was making the same mistakes, by not dispatching a single soldier to punish Liangzuo for his recent attack:

Although Liangzuo rejects beneficence and opposes virtue in this manner, His Majesty is unable to issue troops to punish him, but can only dispatch emissaries bearing imperial edicts. These [Liangzuo] refuses to accept, humiliating our envoys and forcing them to bow their heads as they grasp the edicts and return home. Thus a great nation [大國] [suffers] unbearable humiliations. That His Majesty, at the start of his reign, should face seeing his authority blocked and the nation humiliated by this mad child is the crime of this and the other ministers.Footnote 35

For Ouyang, this current humiliation was deeply rooted in Song willingness to accede to decades of feigned Tangut fealty, as they expanded their territory and came to match the Khitan as a threat to the realm. From the Chanyuan treaty through the eve of the war with Yuanhao in 1038, Song courtiers used Xia compliance as an excuse to let military training and preparations lapse, granting Yuanhao an opportunity to gain information while looking for an opening. Then, when Yuanhao's armies were ready, “he sent a threatening letter, leaving us scrambling with no idea what to do … so that all our early battles ended in defeat. Finally the court employed Han Qi and Fan Zhongyan to take over western affairs, who put all their effort into managing [the war].” Over several years we finally came up with an adequate response, but “ even so all under heaven was overburdened, so we had to compromise [屈意] and accept humiliation by once again making peace. And that is the Qingli experience [此慶歷之事爾].”Footnote 36

In Ouyang's view, the main lesson of the Qingli war was that the court must “employ the strategy of first launching preemptive attacks in order to force [the Tanguts] to exhaust themselves in mounting a defense.” Ouyang's call for preemptive war applied as well to the long-held desire to clientalize the Hengshan Tibetans so recently called for by Cheng Kan. The best way to bring the Tibetans and with them the valuable Hengshan highlands into the Song fold, Ouyang insists, is to first demonstrate “victorious and awesome power” 先藉勝捷之威 against Liangzuo, “so that the Tibetans will realize the strength of the Middle Kingdom and thus desire to submit. From this perspective, it is going on the offensive that brings gains [以出攻為利矣].”Footnote 37

Ouyang ends his recommendations on a note of frustration that despite enemy horses having penetrated the border, none of the circuit-level border officials (the Military-Pacification Commissioners) had offered any plans of action, raising fears that a sense of impassivity replicating that on the eve of the Qingli war had set in. But he takes some comfort in the fact that his chief councilor and Qingli comrade, Han Qi, had “recently assembled and submitted the huge mountain of deliberations from the Qingli era, which is a start to tackling the frontier issue. Qi is also worried that the matter isn't being adequately studied, so he is using these documents as a guide to compel the [policymaking] group into collective discussion.”Footnote 38

Han Qi

Indeed no one was in a better position to compel discussion of the frontier crisis than Han Qi. After being exiled from court for his championship of the Qingli reforms and his opposition to the Qingli peace, Han resumed his place at the center of border affairs as the chief military and administrative officer in Hebei and Shanxi from 1048 to 1055.Footnote 39 Moreover, as a main architect of both Yingzong's selection as heir and his liberation from a year-long regency under Dowager Empress Cao, Han Qi had the trust of his 32-year old emperor.Footnote 40 Han used both his wartime experience and his affinity with the emperor to turn the lessons of the war with Yuanhao into a concrete policy for dealing with Liangzuo: the mass conscription of the Shaanxi population. Like many military planners before and after (including Wang Anshi), Han glorified the Tang practice of registering the entire population as soldiers, “so that even though the numbers were substantial [the cost of provisioning them] was small.”Footnote 41 From the collapse of the Tang fubing 府兵 system on, popular conscription was replaced by the expensive practice of hiring professional soldiers. But Han saw an alternative in the ancillary system of 150,000 yiyong 義勇 militia mobilized in Hebei and 80,000 militia in Hedong, all linked to their communities by ties of property and family and lacking only a bit of drill to replicate the ostensible effectiveness of the Tang fubing system.Footnote 42 The Qingli war had elicited a similar mechanism in Shaanxi, which Han sought to reinstate against Liangzuo:

In Shaanxi, at the start of the Western Affair we also chose one of every three adult males to serve in the local archers auxiliary [弓手]. Afterward they were tattooed to serve as members of the regular Baojie brigades [保捷正軍], but once the Xia Nation submitted, the court released [the local conscripts] so that now few still exist. Hebei, Hedong, and Shaanxi all help protect the northwest, and should be treated as a single unit. Now, if (as in Hedong and Hebei) we also assemble yiyong militia in each Shaanxi prefecture, and just tattoo them on the back of the hand, while letting everyone know that we will not again tattoo their faces, then there can be little alarm.Footnote 43

Although Han recommended launching the measure in just three prefectures, to assess the level of disruption, Yingzong—in a rare departure from the post-Qingli rejection of parabellum measures—authorized the registration and tattooing of commoners for militia service in all but two of the prefectures of Shaanxi.Footnote 44 With an organizational plan that anticipated the baojia policy of Wang Anshi, one of every three adult males per family were conscripted into battalions of 500 men each, mustered in the tenth month of the year for one month of drill and review.

With a reported yield in Shaanxi of 156,873 militiamen, Han Qi's reimplementation of the Qingli model constituted a major step towards the full militarization of the North China population that would occur under Shenzong and Wang Anshi. At the same time, the court followed a second Qingli precedent by expanding its recruitment of Tibetan auxiliaries. In a move that anticipated the increasing participation of eunuchs in the military campaigns under Shenzong and his sons, four eunuch agents of the court were granted the powerful post of circuit zone commander (鈐轄) and manager of their respective circuit's Tibetan affairs and charged with conducting a census of the tribal population and organizing their men into military units. Their efforts registered 106,526 Tibetan auxiliaries and 19,264 horses, who were garrisoned in 72 installations arrayed throughout the four military circuits of pre-Shenzong era Shaanxi.Footnote 45

Sima Guang

As the first remobilization of the Shaanxi population since the end of the Qingli war these two recruitment campaigns provoked a bevy of critics, but none were more vociferous or better placed than Sima Guang.Footnote 46 Sima believed in the need for sound defensive preparation, but he opposed disrupting the lives of the people in pursuit of the chimerical goals of the state. For this reason, Sima viewed the Qingli conscription policies touted by Han Qi as a model of failure, not success. At the same time that Han Qi was at the head of the team commanding the Qingli war the twenty-four-year old Sima Guang was in Shaanxi to mourn his father, from which perspective he had witnessed the impact of military conscription first hand.Footnote 47 For Sima, the conscription measure not only upended Shaanxi society, by violating the initial promise to limit conscription to local defensive duty it also undermined the people's trust in the government. In Sima's words,

In the Kangding (1040) and Qingli era, when the people of Shaanxi were registered for service in the rural militia [鄉弓手], the edict clearly guaranteed that conscripts would only be assigned to local defense, and would not be tattooed and garrisoned along the frontier as members of the regular army. But in no time they were all tattooed and impressed into the Baojie brigades and garrisoned on the frontier. At that time I was in mourning in Shaanxi and saw the results first hand: when these farmers who had long lived in peace, with no knowledge of war, were sent off to the frontier, everywhere west of Shanzhou people in the lanes were as if in mourning; families were robbed, and the government shackled the parents, wives, and children of those who fled, and sold their lands and gardens to provide funds for rewards. After they were tattooed on the face the drill instructors would estimate their family wealth, stealing everything possible; if the conscript couldn't supply his own clothing and food then the costs would be taken from the family property.Footnote 48

In addition, according to Sima, because prefectural and county officials were obliged to meet their mobilization quotas, when a conscript died a male descendant would be branded in his place, so that “one third of the sons and grandsons of Shaanxi are always bound as soldiers.” Once tattooed, the militia conscripts were ensnared into a nether world that one historian has termed the Song “penal-military complex.” As Sima put it: “Once a commoner is branded on the hand then he is bound for life; whichever way he turns people will be frightened, whatever he might say.”Footnote 49

Worst of all, for Sima, none of the harms visited on the people by militia conscription were offset by gains to the state. In direct contrast to Han Qi's claims, Sima insisted that mass conscription had contributed nothing to the Qingli war, for

in the end, we were still unable to expel a single (Tangut) brigade or cross the border [ourselves] in order to punish [Yuanhao] for his crimes. We could not avoid harboring the filth of shame in our mouths, by granting him sham titles and seducing him with weighty bribes just to bring the trouble to an end. At that time the three [frontier circuits] mounted several hundred thousands of new rural militia [鄉兵], but did that give us the power to capture the One Man (Yuanhao)? From this vantage point we can see that the yiyong militia were of no use.Footnote 50

Finally, Sima insisted that the notion of replicating in Song the classical and Tang practice of linking military service to the rural population was fanciful. For whereas military service was an organic part of Tang life, now—in contrast to either the Tang fubing or Song regular army—no nominal chain of command could displace the village-level, familistic organization of the local conscripts, nor could any mock simulation of war conducted during peacetime drill prevent conscripts from fleeing like rats at first news of the enemy's approach. The entire operation, for Sima, resembled child's play. And “How can we base a national strategy on a policy that disrupts the population of an entire circuit and forces the people to dismantle their households and lose their livelihoods, when it is just child's play?”Footnote 51

In sum, the defensive strategies followed in the Qingli war constituted, for Sima Guang, “an eternal warning to the Nation” of what to avoid (國家當永以為戒, 4919). But when Sima personally urged Yingzong to rescind the conscription edict the emperor responded that “The order has already been enacted.” For Sima, the swiftness and secrecy surrounding promulgation of the militia measure represented a troubling trend away from the collective decision-making of earlier reigns that subjected policy initiatives to full discussion, review and correction.Footnote 52

Now in all great matters of the realm, it is only the several great ministers in the Two Administrations [二府, that is, the Secretariat-Chancellery and the Bureau of Military Affairs] who discuss them, enveloped in deep secrecy; not a single official outside [this circle] knows what is going on, and even the remonstrance officials only get to know after an order has been promulgated. If there is something amiss that would require discussion point by point, [they repeat that phrase] ‘the policy has already been implemented, and changing it would be difficult.’ In this way, no misguided national policies ever get corrected. In this regard, it is not only this one ignorant official who is of no use, the entire remonstrance apparatus might as well be abolished.Footnote 53

The re-mobilization of late 1064 heralded what would become two defining characteristics of wartime policymaking. The first was identified by Sima Guang himself: an increasing emphasis on secrecy and the progressive narrowing of the circle of policymakers, as a minority of pro-war activists working in conjunction with the emperor sought to sequester their initiatives from the conciliar legislative process that was meant to be the norm. The second was embodied by the squabble between Sima and Han Qi: the growing tension between those agencies of government—such as the Secretariat—that housed the proponents of war, and those branches—such as the remonstrance bureau, the censorate, prefectural administrators, and, to a surprising extent, the Bureau of Military Affairs (樞密院, hereafter BMA)—that served as platforms for anti-war positions. These points of tension would not explode into the open until Shenzong's reign, but the last years of Yingzong's short reign provided anticipations.

The Dashuncheng turning point, 1066.9

On the frontier itself, the 1064 troop surge did not initially alter the passive Song strategy of overlooking Xia encroachments or issuing impotent warnings. But in the ninth month of 1066 Liangzuo took the field himself for a large-scale attack on Qingzhou's Dashuncheng that pushed the Song towards a more muscular posture (please refer back to Figure 3). On the field of battle, careful advance preparations enabled the Huanqing Military-Pacification Commissioner, Cai Ting 蔡挺 (1014–1076), to successfully deploy crossbowmen, commandos, and Tibetan auxiliaries to prevent Liangzuo and his several myriad of cavalry and infantry from overwhelming the region's forts. Though soon to die, Yingzong was so pleased by this rare example of Song tactical competence that he sent Cai Ting an imperial missive with which to congratulate the troops.Footnote 54 But there remained the question of how to punish Liangzuo. From the field, the Fuyan Military-Pacification Commissioner Lu Shen 陸詵 (1012–1070) argued that the Court's excessive indulgence was responsible for Liangzuo's unruly behavior, and he urged a stern rebuke.Footnote 55 But when Yingzong, now on his sick-bed, asked his two senior advisors for their opinions the results were mixed. Chief Councilor Han Qi, seconding Lu Shen, counseled not only sending an emissary to Liangzuo with a demand for an explanation, but also the immediate cessation of annual payments. The Bureau of Military Affairs Commissioner Wen Yanbo 文彥博 (1006–1097), however, worried that this would create an even greater rift on the frontier and reminded the emperor of the defeats suffered at the start of the Qingli war. But, as in 1064, Han put a positive spin on the Qingli lessons, insisting that “Now our frontier defensive preparations are much better than in those days. What's more, Liangzuo is just a wild child [狂童]; how can he be compared to Yuanhao? If we warn him, he will obey.” Siding with Han Qi, Yingzong dispatched an emissary across the border to the Xia town of Youzhou 宥州, where a dejected Liangzuo, worried about losing his annual subsidy, blamed the transgressions on a rogue frontier official who had since been executed (5063). When asked by Han Qi if Liangzuo had repented for his crimes, Yingzong—who was to die in the first month of 1067—replied: “It is as you predicted.”Footnote 56

Events suggest that Liangzuo's Dashuncheng attack pushed both Yingzong and his officials at court and in the field towards a more proactive defensive posture. Immediately following Cai Ting's victory, Yingzong skirted post-Chanyuan practice by appointing the military commander Guo Kui 郭逵 (1022–1088)—already a co-signatory (同簽書) of the Bureau of Military Affairs—as Military High Commissioner for Border Affairs of the four circuits of Shaanxi (陝西四路沿邊宣撫使), the first Shaanxi high commissioner since the Qingli war.Footnote 57 Around the same time, Xue Xiang 薛向 (1016–1081), a seasoned provisioning expert and financial administrator who as Shaanxi fiscal intendant had salvaged both the frontier horse-marketing system and the government's Jiezhou 解州 salt monopoly, submitted a series of memorials on frontier defense that advocated—among other measures—imposing a punitive economic embargo on the Tanguts and subjecting them to preemptive “near-distance” attacks (淺攻). Rather than following the usual pattern of dismissing such calls as provocative, Yingzong expressed admiration for the proposals.Footnote 58 Moreover, as Wen Yanbo explained the next year to Yingzong's son and successor Shenzong, in the aftermath of Dashuncheng the BMA and the Secretariat had already collaborated to enact the kinds of defensive improvements called for by Xue Xiang, including intensified troop training and mobilizing the Hengshan tribes to disrupt the Xia regime from within. But Wen also emphasized what he had said to Shenzong's father just two months before his death: if Liangzuo continues to obstinately separate himself from the Court, then when it comes to quelling his thugs (兇渠) and coopting his clients everything is permissible. But if he is submissive and remorseful for his transgressions then we should be tolerant and forgiving, that is, the halter and bridle (the loose rein) should not be cut. “Moreover when it comes to the Sovereign's Army, if the situation is not unavoidable how can it be lightly put to use [非不得已豈宜輕用]?”Footnote 59

Abandoning Chanyuan

In sum, the provocations of 1064 and 1066 had shown the Tanguts to be too restive to abide by the Chanyuan rules of generous subventions in return for border stability, thus rendering Renzong's policy of forbearance untenable. In an edict to Liangzuo of 1067.8 Shenzong formally decried half a decade of increasing Xia campaigns to intimidate and seize frontier tribal households, invade and destroy border farmlands, attack the local populace, and seduce Song army deserters with bounties and offers of office. While insisting that the Xia ruler cease such provocations and abide by the Qingli accords, the edict threatened no military action.Footnote 60 But Shenzong had already given his tacit approval to a countermove by the minor military official Chong E, a son of Fan Zhongyan's military aide Chong Shiheng. With the support and encouragement of Xue Xiang and the emperor himself, Chong became the catalyst for a series of cooptations and seizures that lay the foundation for Shenzong's irredentist wars. But as this brief summary will suggest, the outcome was in no way predetermined.Footnote 61

The cooptations were two-fold. In mid-1067 Chong, newly appointed to his father's old post as Administrator of Qingjiancheng, persuaded his civilian Military Commissioner Lu Shen to let him entice a powerful Hengshan chieftain into defecting from the Tanguts to the Song. In a personal audience of 1067.6 Xue Xiang trumpeted the plan to Shenzong, who showed his approval by providing fifty liang of gold to encourage further defections.Footnote 62 But Chong's prime target for cooption was Weiming Shan, the son of a Tibetan subject of the Song who was captured by Yuanhao at age nine, later rising to the position of chief of the Yin-Xia-Sui Army Superintendency (軍司).Footnote 63 In a memorial co-sponsored by Xue Xiang, Chong claimed that Weiming had signaled a desire to submit with his tribal followers out of exhaustion at Liangzuo's wars and fears that they were to be forcibly relocated west to Xingzhou.Footnote 64 Shenzong enthusiastically endorsed the memorial, and ordered Xue Xiang back to Yanzhou to secretly plan the mission with Chong and his supervisor Lu Shen.

The imperial veil of secrecy was quickly pierced by Sima Guang, who as a newly appointed censor not only denounced Chong's plan but even derided the actions taken during Renzong's Qingli war. Sima urged Shenzong to continue the “soft embrace” (懷柔) of the post-Chanyuan decades that made Guanzhong so prosperous, rather than the punitive war (征伐) Renzong launched in response to Yuanhao's rebellion that just humiliated the sovereign and left Guanzhong and the nation as a whole drained. And he entreated Shenzong to ignore the blandishments of warmongering “policy adventurists” (進謀者) “using their persuasive mouths and silvery tongues to fool and delude the emperor” in search of promotions for themselves and rewards for the troops. Ultimately their mad ideas will provoke the Tanguts to attack en masse, “overpowering our soldiers and killing our generals.” We will have to “raise troops and move around resources to salvage the crisis, imposing on all under heaven the same sorrow and woe as in the Kangding and Qingli eras. Then after a while we'll have no choice but to swallow humiliation and summon [Liangzuo back into the fold], employ humble phrases [in our decrees to] him, glorify his title in order to please him, and increase our bribes in order to satisfy him.”Footnote 65

A second censor, Teng Fu 滕甫 (1020–1090), was more concerned about confusion over strategy among Shenzong's senior advisors: “Whether to attack or defend are great matters, on which hinges peace or chaos. Now the Secretariat [Han Qi and Zeng Gongliang 曾公亮, 998–1078] want to go on the attack, while the Bureau of Military Affairs [under Wen Yanbo] favors defense. How [under these circumstances] can we command all under Heaven? I wish that the great ministers be ordered to first come to agreement before they order the troops to defend or attack.”Footnote 66 Although Shenzong was said to have agreed, events were about to move beyond the control of the great ministers of the court.

Seizing Suizhou

Sources vary on the details of the simultaneous cooption of Weiming Shan and seizure of Old Suizhou, but each of the two main accounts reveals individuals conniving beyond the control of their nominal principals to further their own interests.Footnote 67 Chong E is at the center of every account. Although Chong was under orders from his supervisor Lu Shen to refrain from cross-border military actions, he was energized by encouragement from the emperor and a rumor of Weiming's desire to submit forwarded by She Jishi 折繼世, a scion of the powerful Hewai 河外 clan who served as patrol inspector in Chong's patronage network.Footnote 68 The rumor was started, without Weiming's knowledge, by a Weiming adjutant who hoped to escape debts owed to Liangzuo by persuading Weiming's subcommanders to defect to the Song. Based on an agreement negotiated with a native intermediary who lied about speaking for Weiming, in 1067.10 Chong and She entered Suizhou and began erecting walls, after which She marched his troops sixty-five miles northwest to Yinzhou where the surprised Weiming was forced by his own followers to submit with 300 tribal chieftains, 45,000 individuals (including 10,000 crack troops), and 100 thousand head of livestock.Footnote 69

The Suizhou Dilemma: Retain or Abandon?

Chong E's seizure of Suizhou and the forced defection of Weiming Shan presented Shenzong with a dilemma that took two years to resolve, as the emperor, his ministers, and his agents in the field vacillated over how to handle Chong's fait accompli. Suizhou occasioned the first major policy dispute of Shenzong's reign, deepening the rift between advocates and opponents of war as an instrument of frontier management and heralding the partisan battles that were to characterize the reigns of Shenzong and his sons.

The first to signal his outrage at Chong's violation of orders was his supervisor Lu Shen. Lu was startled on receiving Chong's battle report, writing to Wen Yanbo that “Ever since the Founding there has never been a situation like this” and insisting that his protégé be arrested for the “unauthorized launching of military forces [擅興兵].”Footnote 70 Lu's influence was compromised by the intervention of Shenzong himself, who ordered Lu transferred to Qinfeng circuit to prevent him from obstructing the mission.Footnote 71 But this imperial involvement in the Suizhou affair just amplified the outrage of critics at court. One month after the seizure, the Hanlin Academician Zheng Xie 鄭獬 (1022–1072) came close to committing an act of lèse-majesté when he asserted that intentionally employing deceitful officials to promote a surprise attack was the behavior of a Warring States hegemon, not that of a newly enthroned emperor who should be devoted to the Founder's vision of peace.

All the world knows that [suborning Weiming Shan and seizing Suizhou] was wrong; only The Sovereign deemed it right, and rashly put it into motion. The hearts of all who have heard about this are chilled. As for Chong E's seizure of Suizhou, had he not received the Emperor's order then would he have dared, in one day, to drive one-thousand troops in attack against the caitiffs without waiting to report [to his superior—that is, Lu Shen]?Footnote 72

Zheng implied that the only way for Shenzong to redeem himself was to start by executing Chong—the epitome of the treacherous official questing for merit and wealth—and broadcasting his fate to all along the frontier. In addition, Chong's associates, including Xue Xiang, must also be punished, and a hand-written edict dispatched to Liangzuo returning to him both Suizhou and the Hengshan expatriates and explaining that all the miscreants had admitted their guilt.

Zheng's call for draconian punishments stemmed from his commitment to a Chanyuan ideal of international trust and culpability—characteristic of the anti-war partisans—that more often than not overlooked violations by the Xia in order to censure reactions by the Song. Because Shenzong had recognized Liangzuo's notional fealty and officially warned frontier officials against stirring up trouble, Chong's assault constituted a violation of trust for which the Song was to blame. As Zheng framed it, “If they attack us without provocation then we have no choice but to respond [with force 我不得已而起應之]; then if our soldiers’ guts are spilled in the ditches and fields the anger of the world will be on them. But now, without cause, we have harassed them first. If they then lead their dogs and sheep in force against us and our forces disobey and hesitate to advance against them, it will be because the anger of all under heaven is against us.” Unless Shenzong placated Liangzuo, Zheng Xie worried that designs on Suizhou and the larger Hengshan region would become a harbinger of war, with its attendant economic disruption, banditry and social unrest.

Like Zheng Xie, the remonstrance official Yang Hui 楊繪 (1032–1088) was willing to sanitize Tangut provocations in the post-Qingli decades in order to denounce the Suizhou activists. In his anodyne depiction, “for the past several decades there have been no alarms [on the northwestern frontier], and the people have been spared the bitterness of war. Could this only be because we have resorted to some silver and silk? [No], it is also because we have depended on sworn oaths … If the court [lets this plan stand] then we will have broken faith with the barbarian, which will cause endless trouble on the frontier.”Footnote 73

Chong's assault provoked the Xia court into offering to trade a Song defector in return for Weiming Shan's extradition. But in direct repudiation of the Xia request Weiming was given a prestige post in the Song military and granted the subject-name of Zhao Huaishun 趙懷順.Footnote 74 Suizhou's fate was harder to decide, however. As Chong had enthused, because it controlled the confluence of three rivers and occupied high terrain surrounded by fertile lands, Suizhou was the ideal place to relocate submitted tribes and military-agricultural colonists (弓箭手) and from which to launch a major offensive to reconquer all the lands south of the Yellow River loop.Footnote 75 For those very reasons, the Tangut leadership was prepared to contest this penetration deep into their territory with all the resources at their command, including retributive counter-attacks elsewhere in Shaanxi and revenge assassinations of Song border officials.Footnote 76 But events paused temporarily when Liangzuo died suddenly in the last month of 1067, vesting power in the hands of the maternal Liang-family handlers of his seven-year-old heir Bingchang (1060–1086, r. 1068–86).Footnote 77 While waiting to gauge the attitude of the new Xia regime, Shenzong pondered whether to keep Suizhou as a strategic boon or return it as an indefensible albatross.

Groping for a Solution: Han Qi vs. Wen Yanbo

To help him decide the matter, he turned to the same two Qingli veterans who had differed over war policy before: durable BMA commissioner Wen Yanbo (tenure 1065.7–1073.4) and his constant sparring partner Han Qi, allowed in 1067.9 to step down from his decade-long tenure as co-chief councilor (tenure 1058.8–1067.9) to serve as Administrator of Xiangzhou. True to Teng Fu's complaint that the BMA and the Secretariat could not agree on matters of offense or defense, Wen Yanbo advised negating Chong's usurpation by returning Suizhou and Weiming Shan to the Tanguts, while Han Qi urged keeping the town and recruiting even more Hengshan defectors. Until circumstance and another act of insubordination settled the matter in late 1069, Shenzong vacillated between his two senior ministers, uncertain until the end of what to do.

Wen Yanbo applied to Suizhou the same logic he had employed after Liangzuo's Dashuncheng assault of 1066 and to the advance deliberations over Xue Xiang and Chong E's plan in mid-1067: since Liangzuo still called himself a subject and presented tribute there was no justification for suddenly attacking him and seizing his territory. As a pragmatist Wen realized that the Suizhou seizure had made war likely, and in 1067.12 he issued a fourteen-point set of instructions to the regional commanders that focused on defense and avoidance of “the failed tactics of the Kangding era” (康定用兵失策).Footnote 78 At the same time, however, Wen derided the minor military mediocrities and rash Guanzhong literati promoting Chong and Xue's plan to seize what had long been caitiff territory, mocked the idea that the court would “haggle with these dogs and sheep and crickets and ants over a few feet and inches of land,” and insisted that orders to abandon Suizhou must be swiftly put into effect.Footnote 79

With his resignation as chief councilor, reluctantly accepted by Shenzong in 1067.9, Han Qi could no longer debate Wen Yanbo in the capacity of head of state, but he had special standing as Shenzong's personally chosen trouble-shooter.Footnote 80 In a personal audience, Shenzong explained that Chong E had commanded Fan defectors from the Xia Nation along with clientalized Native households from Qingjian to cross directly over the border into the region of Xiazhou. “Neither his commander Lu Shen nor Xue Xiang knew about this in advance.” The emperor reassigned Han Qi to a new post as Administrator of Yongxingjun and Military Pacification Commissioner of Shaanxi, arming him with memorials from the field to bring him up to date and pressing him to be on the road in two or three days so he could give the matter his most urgent attention.Footnote 81 Han arrived in Chang'an in 1067.12 and remained for half a year, until 1068.7. During that time Shenzong communicated with Han personally through hand-written inquiries carried back and forth by the eunuch servitor Wang Zhaoming 王昭明.Footnote 82

Han's “Family Biography” (家傳), a major source for Han's Suizhou memorials, records a gradual hardening of his posture towards the Tanguts that would help inform Shenzong's evolving grand strategy. While still in Kaifeng Han shared the same outrage at Chong E's temerity as his more anti-war colleagues, assailing the effrontery of a scamp (小子) and mere fort commander in rounding up Xia defectors and tribal households to attack across the Song–Xia border at a time when the Han, Native, and military colonist population of Shaanxi was troubled by drought, frost, and destruction of the buckwheat crop. Han also held the government (which he recently headed) responsible for abetting Chong's “reckless, credit-seeking, and unsanctioned act” by ordering the frontier circuits to accept the Hengshan refugees; and blamed Chong's ability to get away with his “reckless folly” on the fact that Shaanxi was under-governed, with three of its Military-Pacification commissioners just “acting incumbents” (權官) and its fiscal intendant newly appointed. Han predicted that Liangzuo would take advantage of Shaanxi's troubles and inadequate defenses to launch a major retaliation; and he urged “His Majesty and the great ministers [of state] to seriously craft a victory strategy and unstintingly provide the financial and manpower resources needed to avoid a great and irreparable national disaster.”Footnote 83

On arriving in Chang'an in 1067.12, Han remained focused on the chaotic disregard for the chain of command (紀律), with “generals leading troops across the border on the basis of nothing more than instructions from neighboring commanders [Chong] or finance officials [Xue].” His first order of business, then, was to warn the region's officers that anyone deploying troops without an order from their commander-in-chief—that is, the circuit Military Pacification commissioners—would be dealt with according to martial law.Footnote 84 But his principal responsibility was to assess the recommendation by Xue Xiang and the veteran general Jia Kui 賈逵 (1010–1078) that Sui be retained under She Jishi's command.Footnote 85 For Han Qi, Liangzuo's murder of Song border officials showed that the Xia were “no longer interested in amity,” and so despite his worries about the collapse of military discipline he endorsed Suizhou as the only workable place to house the Hengshan defectors, whose surrender the court had already accepted.Footnote 86 In Han's view,

If [the displaced exiles] are all transferred to reside in interior towns and forts not only will there be no place for them to live, but the various chieftains will not want to be separated to reside separately from their subordinate tribal families. I fear this will upset men's emotions and give rise to other problems. Moreover Suizhou's walls have now been repaired, and within the Suizhou precincts is abundant fertile, empty land. If we order the submitted Weiming Shan, along with She Jishi, to occupy Suizhou, and have those under him all reside in the nearby lands within Suizhou, then everyone will know that their livelihood is assured and that they can support themselves, and so will combine efforts to fend off Liangzuo.

By contrast, Han argued, if we now “turn around and abandon [Suizhou] we will be signaling weakness,” at a time when Song troops had enjoyed successive victories over the Westerners.

We will be opening ourselves to humiliation, and [the Tanguts] will become so arrogant that even if in the future they want to submit they'll be unable to. But if we confer Suizhou on Weiming Shan, this will complete the court's promise. If we are especially generous towards She Jishi and Weiming Shan even beyond their own expectations, then they must serve us with their lives in order to recompense the court; this is to use barbarians to attack barbarians, at no cost to the nation.

Han stressed that he endorsed the Xue-Jia plan exclusively because it suited the current border situation, but he recommended that Suizhou neither receive provisions nor be protected by imperial or provincial troops.

So as to not expend the nation's wealth and provisions or compete over this [otherwise] useless piece of land, I urge that we grant [Weiming and She] just the empty town and have their several myriad soldiers restrain the westerners with their lives. If in the future these two are unable to defend against the westerners and lose Suizhou, the nation will not be harmed at all, so whatever is destroyed by or lost to Liangzuo will bring him no advantage.

The conditional nature of Han's support for keeping Suizhou was enhanced by Liangzuo's death at the end of the year, which provided the possibility that better relations might be furthered by returning Suizhou if negotiations so warranted.Footnote 87 But a Tangut attack of 1068.5 on Bilicheng 篳篥城, midway between Qinzhou and Old Guwei and at the opposite corner of Shaanxi from Suizhou, convinced Han that the time for prevarication had ended. In a series of memorials from mid-1068, Han folded Suizhou into a larger plan that drew on Fan Zhongyan's call for massive wall-building (大為城寨) during the Qingli phase of the war.Footnote 88 The particulars of Han's plan were animated by a vision of the Xia as successors in both territory and potency to the Han-era Xiongnü, first annexing the oasis states of the west and now linking up with the Qiang Tibetans to their south. In the same way that conquest of the Gansu Corridor had emboldened Yuanhao to “usurp an imperial title and rebel against the court” in 1038, the Tanguts had taken advantage of the Qingli accords to turn their attention to the intermingled submitted and independent (or “cooked” (熟) and “raw” (生)) Fan tribes in the region of Qinzhou (where Han served as Administrator in the Qingli war) and Weizhou, steadily undermining their reliability as a defensive buffer. As reported by Xia defectors, the Tanguts were already gloating about “taking the Western Fan, then using our [Tangut] troops to control the strategic points, from which we can then seize all the prefectures of western Sichuan. If we [Tanguts start by] attacking the Native Tibetans of Qin and Wei, we're already halfway there.”Footnote 89 Tangut ambitions in the region were abetted by the continued feuding among Jiaosiluo's descendants, especially Muzheng, as the splinter groups secretly allied themselves with the Xia. Han worried that “If [the feuding parties] are completely seduced by the Xi Xia, then not only will Guwei be isolated, but all the forts of Qinzhou and the west will be imperiled daily by the [Xia] bandits.” Han was especially alarmed that the Tanguts had capitalized on their advances in the region by establishing an imposing and fully staffed “detached yamen” 行衙 a mere 120 li from Guwei Stockade, in unprecedented proximity to Shaanxi's pre-expansionist border.

By way of a solution, Han requested permission to “choose strategic sites in all the [Shaanxi] circuits to erect new town walls and forts [城寨],” especially in Bilicheng.Footnote 90 In anticipation of Wang Shao's later prediction that military expansion could be self-financing, Han argued that the re-walled Bilicheng, with sufficient land to house 700 to 800 military colonists, could pay for itself by serving as the site of a lucrative wine-tax station. And he put his proposal in diplomatic context, by casting it as a response to the dithering of the Xia themselves: “By urging that we wall Bili it is not that I like to stir up trouble. It is just that I want us to take advantage of the opportunity to wall provided by the fact that the Westerners have not yet decided to reestablish peaceful relations.”

When his proposal came up against opposition from the Bureau of Military Affairs, an exhausted Han (now sixty-one years old) begged release from his frontier position.Footnote 91 At the same time, although skirmishes between Xia and Song troops continued through 1068 and 1069, Bingchang's Liang regents deemed it prudent to make overtures of fealty to both the Liao and the Song, for which they were rewarded with patents investing Bingchang as ruler of the Xia Nation from the Khitan in 1068.10 and the Song in 1069.2.Footnote 92 Shenzong remained frustrated with Xia unpredictability, complaining that “each time we have tried to end warfare they have been completely reckless, leading to [nothing but] regret.”Footnote 93 But with Han Qi's resignation from his Shaanxi post Shenzong turned to Wen Yanbo to come up with a plan for defending the frontier, giving Wen an opportunity to jettison Suizhou by trading the town back to the Xia in return for two Song forts they had captured during the Qingli war: Anyuanzhai 安遠寨 and Saimenzhai 塞門寨, some fifty miles northwest of Yanzhou. At first the Bingchang regime refused the offer, but with the exchange of oaths in 1069.3 the trade became mutually palatable, and came very close to succeeding.Footnote 94 Earlier on Wen Yanbo and Shenzong had sent the seasoned official Han Zhen 韓縝 (1019–1097, unrelated to Han Qi) to the border to negotiate the deal with a Xia emissary, and Han Zhen had received assurances that the Song would not only receive control of the two forts but of the land and minor fortifications around them. In 1069.10 the actual transaction was delegated to Guo Kui, whose chief of staff Zhao Xie 趙卨 insisted—on Guo Kui's orders—that the Xia first relinquish control of the fort perimeters before Song would give up Suizhou.Footnote 95 At this the Xia negotiator replied “By fort [we mean] the fort foundations only; where do the surrounding lands come in?”

Now a town first gained by one violation of orders was retained by another. Guo Kui was already in possession of an edict to incinerate the Suizhou structures before turning over the town, so when he abruptly dispatched Zhao Xie back to Kaifeng to report on the impasse both Shenzong and Wen Yanbo were terrified that they had prematurely ordered the destruction of their newly captured town before regaining the two lost forts. But vowing to “die defending the town” rather than let the Middle Kingdom be sold out by the Tanguts, Guo had disregarded the initial order, revealing it to his staff only after a second panicked instruction arrived from the capital nullifying the burn edict and urgently requesting an update. With that Guo sent the welcome news that Suizhou still stood, and he impeached himself for the crime of violating an imperial edict. The grateful emperor praised Guo, saying “With officials like this I'll have no worries to the west”; and in 1069.10 he rescinded the territorial exchange and ordered that Suizhou be re-walled, its name changed to Suidecheng, and Guo authorized to select the entire slate of officials, from the Administrator on down. At the same time the two “Native officials” She Jishi and Weiming Shan were promoted for their defense of Suizhou, and Weiming honored with the imperial surname Zhao, and the personal name “Embracing Compliance” (壞順).

Conclusion: Embracing War

Conferral of the name “Suidecheng” not only brought the two-year Suizhou affair to an end, it also signified a reversal of national strategy from a dependence on forbearance and the purchase of peace to the glorification of preemption and irredentist war. In concert with his activist prime minister Wang Anshi, Shenzong came just shy of overturning the Chanyuan model completely, as the two men vowed to seek redress for the humiliation and costs imposed on the Song by the treaties with Liao and Xi Xia.Footnote 96 In service towards that end, they mobilized the nation for war through Wang Anshi's New Policies, which yoked the economic resources of the market economy to the military imperatives of the state, while conscripting the local population into paramilitary baojia 保甲 units that in the northern provinces of Shaanxi, Hedong, and Hebei transformed rural society into auxiliary forces of the regular army. At the same time, they reversed sixty years of anti-expansionist injunctions by rewarding the advocates of increasingly expansive campaigns against the Tanguts in the north, as well as protracted wars of colonization and economic expropriation against the Qingtang Tibetans in the northwest, the Native tribes of Sichuan and Hunan in the south, and the frontier communities in the highlands between the Song and Vietnam.Footnote 97

This full mobilization of the nation for war fractured the Song political elite and went well beyond the expectations of even the former Qingli reformers and anti-Tangut hardliners, including the leading pre-Shenzong proponent of remilitarizing Shaanxi: Han Qi. After Han was vilified for memorializing against the exploitative “green sprouts” (青苗) policy in 1070 he vowed to say no more about Wang Anshi's reforms, but in early 1075 he was summoned by Shenzong to offer advice on how to manage Khitan insistence on renegotiating a stretch of the Hedong border.Footnote 98 In contrast with Shenzong's characterization of the Khitan actions as obstreperous and driven by greed, Han Qi attributed their demands to a fear that Song expansion was ultimately aimed at recovering Liao-controlled territory. Assuming a Liao standpoint, Han itemized a number of Song actions that would be particularly concerning to the Khitan: Song outreach to Gaoli, Wang Shao's murderous campaigns in Qingtang, including against Liao affines; fortification of the Song–Liao frontier in Hedong and Hebei; reorganization of the northern population into baojia units; and the deployment of thirty-seven new jiang 將 regiments (of between 2000 to 5000 men each) in Hebei.Footnote 99

Han Qi also took the opportunity provided by Shenzong's summons to renew his critique of the New Policies, whose ill-advised rationale he caricatured as follows: “The foundation of governance lies in prioritizing the acquisition of wealth and military power 富強. Once [we have] amassed financial resources, stockpiled grain, and merged the army and the people [via baojia] then we can lash the Four Barbarians and completely recover the old Tang borders (6389).” And he inveighed against the “attack-minded strategists” 好進之人 who regaled Shenzong with delusional claims that if a sage emperor like him “selected generals to lead massive forces deep into enemy territory, then the lands of You and Ji (that is, the Sixteen Prefectures) could be recovered in a trice (6390).”

Han Qi's indictment illustrates just how far the New Policies fusion of irredentist war and statist domination had departed from the Qingli vision of political reform and limited military preemption championed two decades earlier by Fan Zhongyan, Ouyang Xiu, and Han Qi himself. But if Han was dismayed by the radicalization of measures he had once proposed, his final advice to the emperor shows how diluted the Chanyuan paradigm had become even for its putative defenders: reject the Khitan territorial claims, he counselled, but otherwise do what is needed to allay Khitan worries and reestablish trust. But then Han added a proviso that would have been unthinkable even in the 1060s: should the Khitan comply with the restoration of amity, then use the months and years to come to nourish the people; select virtuous, able, and loyal officials; and oust the traitorous flatterers, so that all under Heaven will once again be happy and compliant—all code for purging the New Policies and their supporters. Then, once

defenses are in order, the frontier replete with grain, and the coffers overflowing with wealth, we can wait for the enemy to enter a state of weakness and disorder. [At that point] we can rise rampant to recover our old borders, relieve the hearts of the loyal and righteous, and requite the anger [that has festered] over successive reigns since the Founders. Your Majesty's achievement will burn brightly, shining in endless glory like the sun (6390).

Han's endorsement of a future campaign against Liao, however measured, was seconded by Fu Bi, another of the elders summoned by Shenzong. Like Han, Fu used his summons to denounce Song expansionism and the New Policies, and to counsel the avoidance of any provocations that might ignite a joint attack by Liao and the Xi Xia. But, also like Han, Fu—who just a few years earlier had urged the newly enthroned Shenzong to abjure all mention of war for twenty years—now promised that if the emperor accepted a bit of humiliation in return for reestablishing calm, prosperity, and the well-being of the people, “in time we can plan for the great undertaking” (然後別圖萬全之舉).Footnote 100

That even the New Policies opponents Han Qi and Fu Bi would pay homage to the prospect of attacking Liao and recovering the Sixteen Prefectures illustrates how thoroughly the accommodationist principles of the Chanyuan model had been supplanted by an acceptance of war. From Shenzong's reign to Huizong's disastrous attempt to seize Yanzhou and the Sixteen Prefectures in 1122, proposals for irredentist wars against the Qingtang Tibetans, the Tanguts, and the Liao themselves became a potent form of political capital, even as the opponents of war were purged from government or silenced by edicts criminalizing debate.Footnote 101 Although Southern Song observers attributed this turn towards irredentist war to the personal ambitions of Shenzong and his sons and the machinations of Wang Anshi and his ministerial successors, I have endeavored to show that its deeper cause was the failure of the Chanyuan-style peace. For while the Chanyuan treaty had established a stable allocation of status, wealth, and territory between two relatively equal parties, Song and Liao, its rules-based accommodationist foundation was not elastic enough to encompass the unrequited aspirations of the Tangut Xi Xia. Even though the Qingli settlement of 1044 seemed poised to return the frontier to a peaceful equilibrium, the fractious Xia leaders were less willing than the Song to regard the fruits of war as satisfactory. This already precarious three-party relationship was further challenged by the collapse of Jiaosiluo's control over Qingtang, further eroding the ability of the Chanyuan model to constrain the competing intrigues, expectations, and demands of a growing constellation of political actors. In the two decades following the Qingli war Renzong's court continued to overlook Xia transgressions and forbid its generals from taking retaliatory military actions, but by the mid-1060s influential officials like Ouyang Xiu and Han Qi openly expressed doubts about the Chanyuan model as a tool for assuring border security. With Liangzuo's attack on Dashuncheng in 1066 those doubts spread to the new Yingzong emperor himself, signaling to such frontier officials as Xue Xiang and Chong E the acceptability of preemptive attacks. Thus when the young and ambitious Shenzong ascended the throne in 1067, the seeds of irredentist war had already been laid by the failure of the Chanyuan peace.