Introduction

Within this article I aim to explore how greater student dialogue in the classroom can drive engagement with ancient drama. As part of the Classical Civilisation A Level specification, students need to demonstrate knowledge and awareness in the examination of how Aristophanes’ Frogs might have been performed on stage and its possible reception by a classical audience. This research investigates how teachers can effectively encourage student discourse in the classroom for students to engage with and analyse Frogs as a piece of comic drama, rather than simply as an A Level set text.

In his research on teaching drama to students, Sanger made the simple but perceptive comment that ‘audiences rarely go into a play cold’ (Sanger, Reference Sanger2001, p.7). Audiences enter the theatre with preconceived ideas about what they are about to see on stage, or the visual representation can provide hints at content and atmosphere (Sanger, Reference Sanger2001). My objective from the four-lesson teaching sequence is to make my audience of ten Year 12 students less ‘cold’ to the world and stage of Aristophanes’ Frogs through student dialogue.

I will be teaching my lesson sequence at an academy in North-East London. The class comprises ten students of mixed prior attainment, with predicted grades at A Level ranging from A to D. In class we have read and analysed the first half of Aristophanes’ Frogs, with these SSA lessons intending to introduce students to the first two rounds of the agon between Aeschylus and Euripides. During the lessons I have chosen to monitor five pupils based on their range of predicted grades and varying levels of confidence and how vocal they are in class. To ensure anonymity these students have been provided with pseudonyms and photocopied work has been anonymised:

• Buffy: predicted A

• Willow: predicted D

• Cordelia: predicted A

• Xander: predicted E

• Giles: predicted C

I shall assess students’ learning through external and my own observations during class, student written feedback at the end of the lesson sequence and students’ work in lessons.

While specific literature on the teaching of ancient drama to Classical Civilisation classes is sparse, there is certainly literature more generally on the theory of dialogic learning. Within this assignment I intend to focus first on dialogic learning theory in general, before refining my focus to assess the effectiveness of group work and drama technique, both of which facilitate opportunities for student discussion. The conclusions drawn will be used to inform my planning and evaluation of the sequence of lessons with Year 12.

Literature review

The benefits of dialogue

Dialogue in the classroom can come in many different forms: questioning; pair or group work; presenting; debating and so on. Crucial for all of these is the emphasis on classroom discourse. Dialogic learning builds on Vygotsky's socio-constructivist approach through the appropriation and use of language to construct learning (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978). Chang-Wells and Wells (Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993) use Vygotsky's core theory to develop their own ideas for using texts and a focus on literacy for the benefit of students’ learning. Within their research, Chang-Wells and Wells outline the key functions that vocal engagement with literature has for students: the ability to gather and organise their ideas in a structured and logical way; the ability to interpret information and apply it in different contexts; and the ability to reflect on their learning process after the learning outcomes have been achieved (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993). The use of dialogue in the classroom empowers students to articulate their thoughts, making them ‘co-participants in the dialogue’ (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993, p.64). This articulation of ideas is crucial for applying existing knowledge and then being able to develop this for additional questions or concepts.

Many researchers have taken different emphases on the role of the teacher in dialogic learning. While Chang-Wells and Wells’ research largely focuses on the student and student voice in the classroom, Alexander puts forward his belief in focusing on both student and teacher dialogue equally for improved learning outcomes (Alexander, Reference Alexander2018). Key to this argument is the role of the teacher in creating the conditions necessary in the classroom for effective student talk: ‘It is largely through the teacher's talk that the students’ talk is facilitated, mediated, probed and extended – or not, as the case may be’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2018, p. 3). Teachers need to ensure a supportive classroom climate, with allocated space and time for pupils to think and respond to each other (Hodgen & Webb, in Swaffield, Reference Hodgen, Webb and Swaffield2008). Through verbalising their thoughts, students are required to reconstruct their pre-existing knowledge, and put it in language to explain to their peers.

In addition, several academics write about the role of dialogue for teachers in formative assessment of pupils. Within Assessment for Learning (AfL), dialogue is an important component for teachers to communicate learning goals, assess students’ learning and explain how to progress (Black & William, Reference Black and Wiliam2010). Similarly, in his influential Visible Learning for Teachers, John Hattie argues that teachers need to encourage and listen to student discussion ‘to be aware of both the processing levels of different aspects of the activity and how each student's response indicates the level at which they are processing’ (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012, p.39). Crucially here, Hattie is focusing on how dialogue and questioning are effective for creating a culture of oral feedback between teacher and student, student and teacher, and student and student.

Dialogue through group work

When reading the literature on dialogic learning theory, I wanted to focus on specific strategies I can employ with my Year 12 class to enable and structure effective dialogue. Collaborative learning through group work builds on the core concepts of dialogic learning to create a more focused consideration of meaningful learning in the classroom. In these small collaborative groups, academics argue that teachers can exploit the opportunity for students to help one another learn (Webb, Troper & Fall, Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). This ‘peer to peer construction’ (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012, p.39) sees students needing to articulate ideas and explain concepts to each other. This student-led approach also enables students to recognise misunderstandings or gaps in their own or their peers’ knowledge and seek to remedy these through explanation or questioning (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). Their argument clearly elucidates the effectiveness of group work in helping pupils learn through this collaborative approach. Students use dialogue not only to share knowledge, but also to question what else it is that they do not already know. Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick (Reference Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick2017) similarly advocate group work in raising the attainment of pupils by increasing ‘children's capacity for dialogue and reflective thought as well as developing subject knowledge’ (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick2017, p.4). Students can also be more perceptive at recognising what peers do not know and can offer explanations in a mutual language (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995), ultimately raising engagement and learning within the classroom. This feedback loop draws on AfL theory, enabling students to recognise their existing knowledge and consider what they need to do to progress.

Dialogue through drama

Another strategy to encourage dialogue and collaborative learning in the classroom is through drama. The nature of Frogs as a comic drama means Year 12 students need to engage with how this play appears on stage, and the social context of the play impacting an Athenian audience's reception of it. Neelands argues for the power of drama ‘in offering young learners a unique relationship with literature and talk’ (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992, p.8). As a practical activity, drama enables students to engage with the literature they are reading with their peers. Students learn to interpret the text and create their own meanings from it (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992). These factors strongly correlate with the Vygotskian view of language as a tool for shared cultural expression and construction of meaning (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978). Activities which aid an understanding of the story as drama (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992) include improvisation of characters commenting on the events of the play, or creating images representing incidents within the story. McGregor et al's (Reference McGregor, Tate and Robinson1977) work provides even clearer guidelines for learning through drama, outlining four key principles which can be used in the classroom: learning to use the process of dramatic interpretation; understanding key topics and themes through acting; presentation; and ‘interpretation and appreciation of dramatic statements by other people’ (McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Tate and Robinson1977, p.25). These principles can be used to guide an exploration of literature through language.

In addition, the use of drama strategies in the classroom encourages students to consider the social context of a play. Neelands (Reference Neelands1992) strongly endorses drama for its ability to develop oracy amongst students. He argues that for students to be truly powerful speakers, they need to be able to analyse the contexts of plays ‘so that they are able to identify the key elements which will have a major bearing on what is said and how it is heard’ (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992, p.19). Through using dialogue to explore, interpret and challenge students with different dramatic contexts, students learn the relationship between language and social context (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992). This will be a crucial part of my sequence analysis when teaching Aristophanes’ Frogs, for which an understanding of its social and dramatic context is key. Neelands (Reference Neelands1992) also describes methods to be used to emphasise the dramatic context of a play. Activities such as creating props, designing costumes or staging, outlining characters or rearranging the classroom to represent specific scenes (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992) encourage students to interpret the words on the page into a physical setting.

Difficulties with dialogue

Most authors state potential pitfalls in testing their theories on dialogic and collaborative learning in the classroom. These will be taken into consideration for the planning of my sequence of lessons. First is the impact that poor instruction from the teacher can have on the effectiveness of the group activities (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). Tasks need to be purposeful, with clear structures for how activities should be carried out. Slavin (Reference Slavin1987) put forward two key criteria to drive purpose in group activities: group reward and individual accountability. This also reduces an element of competition from the classroom. Ensuring that students know what they are aiming for, and how they will get there, will increase productiveness and the effectiveness of achieving the learning outcomes.

Another potential limitation on effective dialogue is a lack of appropriate rules for conducting discussion. Space needs to be created for all students to feel able to contribute their views (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012), and for appropriate time to be allocated for reflection or explanation in the event of misunderstanding or contradiction (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). Using discussion to question ideas, work towards a solution or justify arguments again encourages students to reflect on their thinking process. This leads to students developing greater ‘self-regulation’ (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012, p.118) over their learning.

A final limitation cited by academics is the question of how to monitor the increase in improved standards through dialogic learning. Limited research into certain strategies, such as the role of verbal explanation in increasing attainment (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995) or the connection of collaborative discussions with ‘learning products’ (Marrtunen & Lauringen, Reference Marrtunen and Laurinen2007, p.113) certainly requires greater attention. For my research I shall be thinking about how best to demonstrate the success of implementing dialogic strategies into my Year 12 Classical Civilisation lessons.

Conclusion

This literature review has focused on the benefits of dialogic teaching, and how this can be used effectively in the classroom. It has also assessed the potential limitations that the role of discussion can have on student engagement and attainment if teachers do not create an environment suitable for discursive activities.

For the planning of my sequence of lessons I shall draw on the strategies proposed by Slavin (Reference Slavin1987) and Alexander (Reference Alexander2018) in creating purposeful and structured group activities. The AfL literature discussed supports the use of dialogue for formative assessment of pupils, as well as the need to plan carefully the opportunities for questioning and feedback to and by students. What is clear from the literature is the need to support a collaborative and reflective atmosphere in the classroom which encourages all students to take part in the dialogue.

The next section of this assignment will look at my planning and evaluation of the sequence of lessons, using these principles to guide their format and assess their effectiveness in promoting learning amongst the Year 12 Classical Civilisation students.

The Lesson Sequence

I used the findings from my literature review to form the basis of my lesson sequence with the Year 12 class. Key to my lesson planning was how greater dialogue can be used to meet the lesson objectives and improve student understanding of the dramatic and social context of Frogs.

I teach this Year 12 class four times a week. For this sequence of lessons (Table 1) three lessons were taught in one week, with the final lesson taking place on the following Monday to allow for review and feedback on the homework task. Each lesson is 55 minutes long.

Lesson 1

Planning

In this first lesson of the sequence (See Table 2 below) I intended to introduce students to the format of the contest between Euripides and Aeschylus and to think about their characterisation onstage. Prior to the lesson sequence, the Year 12 class had read through the opening statements of Aeschylus and Euripides and briefly discussed students’ impression of the two characters. In the starter activity I planned to recap on what was read last lesson and encourage students to analyse the key characters’ portrayal by Aristophanes (Neelands, 2013). To do so I planned to provide students with a list of quotes from the section previously read and ask students to work out in pairs who the quotes were describing. My intention was to then use oral feedback from students and class discussion to assess the process students had used to work out the correct answers (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993), and pull out key themes from the quotes related to the characters.

I also wanted students to understand how this contest in Frogs was going to be judged, as this was something I learnt in the previous lesson that not all students had understood from the reading. I planned a bingo-style activity with questions on the board for pairs to find the answers in a certain section of text. The purpose of this was to encourage a collaborative atmosphere in the classroom (Hodgen & Webb, in Swaffield, Reference Hodgen, Webb and Swaffield2008) where dialogue was crucial to achieve and prove success in the task. This activity was planned to set up the atmosphere for the second key activity of the lesson: reading and analysing in groups the first round of the contest between Euripides and Aeschylus. With Slavin's (Reference Slavin1987) advice in mind on group reward and individual accountability, I planned to sort the class into groups of three and give each person a specific section of text to read with associated questions. I also allocated time at the end of the lesson for each group to present back to the class, drawing on Hattie's concept of ‘peer-to-peer construction’ (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012, p.39). Here I had two aims: first, for students to process their understanding to be able to explain to others (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993); and second, for students to receive explanation from their peers in accessible language (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995).

Evaluation

As the second lesson of Monday morning, students were still fairly dynamic from their weekends and appeared engaged with the collaborative and problem-solving nature of the starter activity. As I circulated through the class, pairs seemed focused on talking through the quotes on the board. During class feedback, students had clearly started to notice patterns in the way in which Aristophanes presents Euripides and Aeschylus in Frogs. Xander, one of the less confident members of my focus group, struggled to decide to whom a quote should be attributed when I chose him to answer. Based on quotations that had already been correctly allocated to Euripides and Aeschylus, I encouraged Xander to explain how the tragedians were being described and reassess which was the right answer for the quotation in question. Through this process Xander was able to work out the correct answer, ‘Oh, it's Euripides because he's clever with words’, showing an awareness of the process he should go through to construct understanding (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993). This same pattern was used again with Willow, another student in my focus group who lacks confidence in answering in class. At this point, Willow was able to self-correct verbally based on the process we had already worked through with Xander.

Students then collaborated in pairs for the bingo-style activity. Buffy and Cordelia, both confident and vocal students, ‘won’ the task, having an active discussion on the best way to work together to find the answers in the text – ‘you take that part and I'll do the bit about the judging’ - and calling out when they had achieved this. While the competition element certainly added a sense of fun to the classroom, while watching students working together I quickly realised that this task strayed away from Slavin's (Reference Slavin1987) model which aims to reduce competition amongst students. Even from this brief exercise I saw that the quieter or less confident students, including Willow and Xander, needed greater prompting to work through the text and were more hesitant in calling out the answers. This was something which I tried to address in the second group activity. Having a set amount of time for the activity, with this group and individual accountability (Slavin, Reference Slavin1987), ensured that each member of the group had the opportunity to engage with the task. In contrast to the previous activity with an uncertain time pressure, students also had the opportunity to ask questions about the text. This allowed me to address any uncertainties or misconceptions (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012).

My attempts to split the text to create this individual responsibility unfortunately resulted in some confusion from students on what they should ultimately be presenting back to the class. Both Giles and Cordelia in different groups asked whether they should be presenting the answers to the questions, or just giving a general summary of themes. At this point I realised the importance of clear teacher instruction for group tasks, as highlighted by Webb et al. (Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). Here, my attempts to manufacture clear boundaries in the task detracted from my clarity of explanation. Despite trying to enforce a positive atmosphere with expectations prior to groups presenting, I failed to provide a task for students to complete based on the group presentations. The teacher observing commented afterwards that students appeared restless and lacked focus during the group presentations. Again, this clarity of explanation will be something to rectify later in the lesson sequence.

Lesson 2

Planning

This lesson (Table 3, below) was designed to develop students’ understanding of how Euripides and Aeschylus are parodied onstage in Frogs. To start this process, I planned to hand out a ‘character outline’ – a stickman drawing of the two characters – for students to write around how these have been portrayed in the play so far, including thoughts about their potential physical manifestation onstage. The intention here was to enhance students’ understanding of the context of the drama (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992) as we progressed through the agon, where further stereotypes and comparisons will be made between the two tragedians. As we ran out of time last lesson, I adapted the lesson plan to allow time for the second half of the groups from the previous lesson to present on Aeschylus’ argument in round one of the agon. Based on my evaluation from the last lesson, I planned clearer guidance for what students needed to do while listening to groups, with students adding to the character outlines based on the presentations. I then planned for students to write modern scripts of round one of the agon, putting into their own words the arguments of Euripides and Aeschylus (McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Tate and Robinson1977). As the final part of this activity I planned to ask students to act out their modern scripts in pairs, with the potential to perform in front of their peers.

Evaluation

The first two lessons of the sequence took place on the same day, so students retained a good amount of knowledge for them to be able to describe perceptively the portrayal of Euripides and Aeschylus in Frogs. Buffy used terms such as ‘avant-garde’ to describe Euripides, and one of my less confident students, Willow, described her impression of Aeschylus as ‘having a long beard and I think maybe he's quite old’. At this point in the lesson sequence, I was pleased with Willow's ability to visualise the characters as they might appear physically onstage (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992).

Even though I had to adapt my lesson plan, the additional time allocated for the group presentations here meant that as a class we were able to recap on the learning from last lesson. Before the group presentations I used my planned questions to build on our prior discussions. Students were able to answer the simpler recall questions when picked to answer – such as ‘Why is Dionysus going down to the underworld?’ – and I used open questioning (Hodgen & Webb, in Swaffield, Reference Hodgen, Webb and Swaffield2008) to try and draw out understanding of the more complex issues relating to the moral message of Frogs. Later in the plenary, I was pleased that Buffy and Cordelia showed understanding of the moral purpose of tragedy to justify their argument that Aeschylus appears to be winning the contest following round one. During the second round of group presentations, students appeared much more engaged when given specific criteria to make notes on while listening to their peers. Giles explained the notes he had made around his character outline of Aeschylus, describing the character as ‘serious and also uses long, complicated words to try and make himself sound more important’.

The activity with students creating their modern scripts was interesting for two key reasons: first, the importance of teacher instruction for effective learning (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995) and second, the success of drama work in setting a play in its dramatic and social context (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992). At first, Xander showed confusion at what he should write and was unable to take the text out of its original context. The back and forth dialogue between myself and Xander helped me to assess the extent to which Xander understood the text. Through discussion I encouraged Xander to explain in his own words what was being said, rather than simply regurgitating what was on the page. Once he realised that the tone did not have to be in formal, archaic language, Xander got much more into the activity. On reading his script later, he had come up with a brilliant retort by Aeschylus to Euripides: ‘Well, your poetry's so bad it's died with you! Should be easy for you to use it now.’ It was clear that students enjoyed this part of the lesson, with several including Giles, Buffy and Cordelia volunteering to read out sections of their text.

Lesson 3

Planning

For this lesson's activity I booked one of the school's computer rooms. The key purpose of this lesson (Table 4, below) was for students to consider the performance of Frogs onstage and its reception by an audience (in different contexts). In the lesson I planned to split students into groups and ask them to adapt Frogs for a 21st century audience. As per Slavin's (Reference Slavin1987) advice on effective structuring of group work, I planned my instructions for groups to include a slide discussing the group's decision on the concept they've chosen, and then slides created by individuals which give further details on one of the following options: the staging of the performance; the characterisation and portrayal onstage of Euripides; and the characterisation and portrayal onstage of Aeschylus. Students would need to draw out the key themes using quotes from the text to justify the group's decisions, which they would ultimately present back to the class. My intention was to encourage communication, creativity and reasoning through students working together in a group (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick2017).

Following my evaluation of group work in previous lessons, I planned my instructions to be much simpler and clearer (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Troper and Fall1995). I also wanted to avoid a lesson in the computer room becoming a ‘gimmick’ and therefore for my planned activities to demonstrate the purpose of the learning objectives (ibid.). My intention at the beginning of the lesson was for students to use their knowledge of topical events in 5th century Athens to consider the potential impact on the thoughts and emotions of an Athenian coming to watch a performance of Frogs for the first time in 406 BC. These same themes could then be used by students for the next activity when thinking about the context of a modern production of Frogs (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992).

Evaluation

Although students were a little more excitable than usual due to the novelty of the lesson taking place in the computer room, many aspects of this lesson were successful. During my planning of this lesson I was concerned to avoid losing ‘control and purpose’ (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992, p.9). I was therefore pleased with my explanation and scaffolding of the lesson's activities. In the starter activity it was clear from students’ feedback that they were able to recall information on the chosen topical events on the board and contribute perceptive views on the impact on an ancient Athenian. Xander put his hand up to offer the opinion that Athenians ‘might have felt dirt-poor and ashamed’ in reference to the Spartan occupation of Decelea, while Cordelia described an atmosphere of ‘fear and uncertainty’ in Athens during the Peloponnesian War. Here I was pleased with students’ ability to interpret and put into their own words the potential emotions of an Athenian audience. This activity set the scene for the next stage of the lesson and I highlighted the key themes discussed as a focus for the rest of the lesson.

The class quickly grasped the purpose of the main activity and seemed excited about what they needed to do. In the first five minutes of discussion I moved between groups to hear and note down their conversations. The snippets I overheard indicated engagement with the task and constructive dialogue between the groups. In his group Giles asked the question ‘Who will we get to play Dionysus? He's a bit ridiculous so maybe someone silly…’ The group with Willow and Xander decided to keep their staging in its ancient context (Picture 3), with Xander explaining that ‘we're keeping it classical but thinking about how to engage a modern audience’. This led to a discussion on how the group would differentiate their portrayal of Euripides and Aeschylus. It was interesting that the group with some of the quieter students decided to retain an ancient context to their production, perhaps indicating a lack of confidence in their knowledge to push their interpretation. Nevertheless, the discussion I had with students indicated that they understood the key themes and my feedback asked the group to think about whether they could push modern stereotypes of ancient Greece for their production.

After ten minutes I reminded the groups of the limited time in the computer room and the responsibility of individuals to produce their own slides. This helped focus the class, which was displaying a tendency to lapse into easy group discussion without producing anything tangible. In future lessons I would consider how to best set up efficient ways of working for groups prior to starting the task. I would consider allocating a certain amount of time for discussion only, before students moved on to working on their computers. This could help create the productive and focused atmosphere of dialogue which Hattie (Reference Hattie2012) advocates. Similarly, this would have helped when problems with Willow and Giles’ computers had the effect of isolating them from the group work. While this was resolved, alternative, clear activities to contribute to the group dynamic would be beneficial in future tasks. The role of technology in aiding learning is interesting, and in his written feedback on the lesson Giles commented that ‘because we're doing it on three different computers [it's] hard to put all ideas into one’. This indicates a more practical consideration when planning lessons with students using technology.

Overall, I was pleased with the ability of the students to understand the key themes of Frogs’ social context and consider these against a modern backdrop. Although at this stage I had not reviewed the groups’ final products (this was to be completed for homework), the discussions in class indicated that students were engaging with the task and considering relevant, interesting concepts, such as using the Vietnam War or 1950s America. In the post-it note reflection on the activity, Willow's comment on its benefit was particularly interesting:

Useful in terms of memory as it helps me relate a situation for so long ago which can be very confusing compared to today.

Xander showed greater understanding of the context of Frogs as a play, stating that the activity ‘helps me understand what type of reaction I would get from watching a play like this in modern day’. However, there was still uncertainty on the portrayal of characters onstage, with his comment that it is hard to think about how the characters would physically look. This will be something I shall pick up during discussions of group presentations in the following lesson.

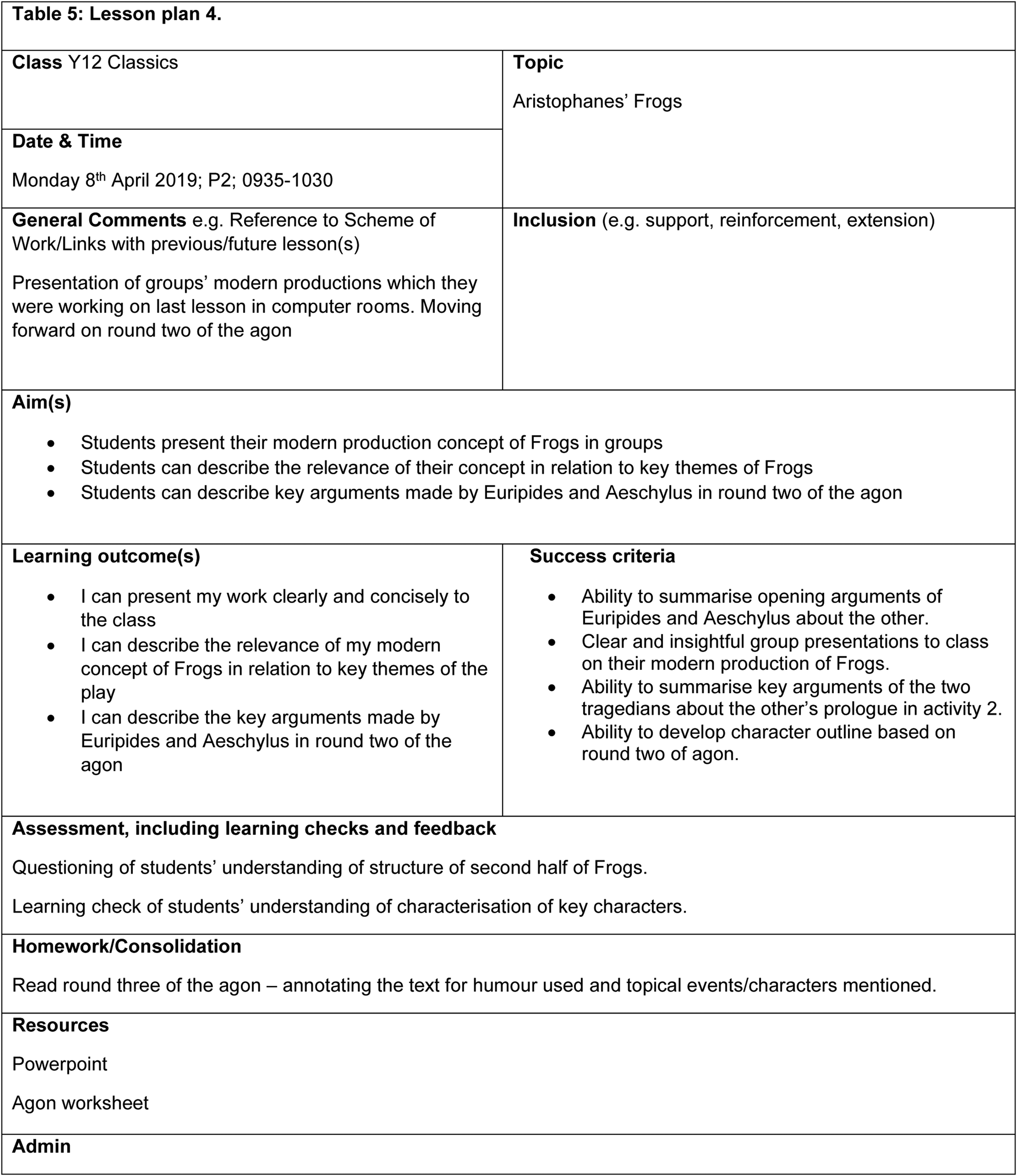

Lesson 4

Planning

In this final lesson of the sequence (Table 5, below) I intended for students to employ skills of presenting and oral feedback. As students were asked to finish their presentations for homework, in this lesson I planned for groups to present back their work. My intention was to dedicate the first half of the lesson entirely to the four group presentations to develop the ‘Exploratory Talk’ spoken about by Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick (Reference Mercer, Hennessy and Warwick2017, p.1) which nurtures critical evaluation of others’ ideas and constructive discussion. Vital for this is the collaborative atmosphere which Hodgen and Webb (in Swaffield, Reference Swaffield2008) and Hattie (Reference Hattie2012) advocate for effective formative assessment and learning by pupils. I planned for a starter activity which got students talking in pairs to summarise the arguments of Euripides and Aeschylus in one sentence for each character. The aim here was to enforce an atmosphere of dialogue and oral feedback, thereby trying to limit nervousness in presenting to their peers. Before the group presentations, I also planned specific criteria in my resources for the class to be thinking about and prepared to feedback on after each group presentation. In the second half of the lesson I planned to move on to round two of the agon, using prior knowledge to elucidate meaning from Euripides and Aeschylus’ arguments and again develop the character outlines.

Evaluation

At the beginning of the lesson certain students expressed nervousness about presenting in front of peers. Even though usually a confident and vocal member of the class, Buffy commented that ‘I hate having to speak in front of people’. The starter activity therefore appeared to help students in recalling their prior knowledge (Marrtunen & Laurinen, Reference Marrtunen and Laurinen2007) of topical and feeding back out loud to the class. From my point of view, students seemed calmer and more confident in approaching the group presentations following this initial task. Before we began, I verbalised my expectations of students when listening to other groups presenting and explained that I wanted students to be thinking about what was particularly effective in each group's modern production.

Both the quality of the work and fluency of presentations reflected students’ ability to understand the social context of Frogs and reconstruct the setting for a modern audience. The first group, including Buffy, presented their concept which transposed the setting of Frogs to that of America during the Vietnam War, cleverly adapting the production's name to Hawks and Doves (See Picture 1). The group was able to explain clearly to the class their choice of modern figures to represent Aeschylus and Euripides in their production, such as Lyndon B. Johnson playing Aeschylus, ‘because of his more traditional politics and was seen more favourably by Americans’ and Euripides by Richard Nixon ‘as he was a lot more controversial and split opinion’. The feedback from students showed engagement with the presentation, with Xander praising the clarity of presentation and the interesting adaptation of Frogs.

Picture 1. Group presentation

Other concepts included Cordelia's group staging Frogs in post-war 1950s America (see Picture 2) with a greater focus on the portrayal and characterisation of the two tragedy-writers. Students appeared to enjoy hearing the other groups’ ideas, supported by Giles’ feedback that he found this activity useful with ‘different people coming up with good ideas that I didn't think of’.

Picture 2. Group presentation

Picture 3. Group presentation

The observer watching the lesson commented afterwards that while it worked well to encourage students to feedback on the positives, I could have asked students to be more critical of the presentations against the criteria set at the beginning of the task, such as the inclusion of quotes or a focus on characters’ physical appearance onstage. Again, greater structuring and targeting of feedback would have been a constructive activity for students watching group presentations. While we did not have enough time at the end of the lesson to complete the final activity in full, I asked students to skim read round two of the agon in preparation for the next lesson and choose further adjectives which support the presentation of Euripides and Aeschylus.

Conclusion

The four lessons revealed greater successes and challenges in dialogic learning than I anticipated right the beginning of my research. Throughout the lesson sequence I tried to improve students’ understanding of Frogs’ dramatic context through drama approaches and group work. From observations of students in class, the quality of their written work and students’ own evaluation of the lessons, I believe that this learning objective has largely been achieved. The use of drama techniques, such as students’ rewriting of a script or the creation of a modern production of Frogs, revealed a closer engagement with the literature to build an understanding of what is said onstage (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992). The articulation of these thoughts was crucial for me to assess the level of their learning (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012) and to encourage students to reflect on how they can read and understand the literature using their own language (Chang-Wells & Wells, Reference Chang-Wells and Wells1993).

During the teaching and evaluation of each lesson I had a growing sense of the importance of the teacher in dialogue within the classroom (Alexander, Reference Alexander2018). It was clear that any activity which uses dialogue as the format of learning requires clear instruction and tangible output to focus students and achieve the lesson objectives. At points during the lesson sequence both my lack of explicit instruction and then over-manufacturing of instructions led to student confusion. The most effective activities were those which had a clear purpose and simple instructions. Specifically, for group work this clarity of instruction is essential for structuring the nature of collaboration between students. While I tried to ensure a collaborative atmosphere (Hattie, Reference Hattie2012) during activities, future work will also aim at greater structuring of effective oral feedback between peers.

Due to the limited amount of time and my own prioritisation I was unable to try certain activities such as improvisation of scenes (McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Tate and Robinson1977) or rearranging the physical layout of the classroom to reflect the drama (Neelands, Reference Neelands1992). With careful development of a collaborative and open atmosphere in the classroom (Hodgen & Webb, in Swaffield, Reference Hodgen, Webb and Swaffield2008) these are tasks I would like to test in future lessons.

Despite its challenges I believe dialogic learning has had its successes with this Year 12 class. At the end of the lesson sequence I was pleased with students’ understanding and subsequent interpretation of Frogs. While dialogic learning clearly necessitates effort to plan and teach effective lessons, this seems an important step to empower students in their learning and, hopefully, help in their enjoyment of ancient comedy.