Introduction

The collective mind often attributes the image of a modern Latin classroom to a teacher writing on a chalkboard in front of students eagerly memorising the declensions in silence. However, as part of their search for innovative and effective practices, Latin instructors have consistently expanded their gaze beyond the traditional parameters of rote memorisation for at least since the pioneering efforts of W.H.D. Rouse, looking to more innovative models presented by novel methods for inspiration and to the halls of predecessors in hopes of fostering a more engaging learning environment. Upon close comparative study between the modern pedagogical methods in Latin classrooms and the perspective of Renaissance scholar Petrarch, this study identified a commonality between the two: emphasis on dialogue between different members of the classroom and personal interpretations of preceding authors’ works for a better opportunity of comprehending the content. Grounded in the philosophies of the Socratic method, Petrarch claimed that an important element of the tradition of pedagogy finds expression in dialogues, imitation, and the significance of fully comprehending the topic in pursuit of wisdom. Likewise, many institutions of the U.K. and the United States, strengthened by the emergence of dialectic assessment applications during the Covid-19 Pandemic, are working towards a new norm in place. After conducting an in-depth interpretation of primary and secondary sources regarding Petrarch's pedagogy, as well as research of its modern developments and the applications, the comparison suggests a new direction for the Classics community to consider going forward.

Background

Latin was no longer spoken as the official language of any European nation by the medieval ages following the downfall of the Roman Empire. Yet the lack of a ubiquitous language among German successors, who established kingdoms in the former regions once belonging to the western Roman Empire, allowed its survival as a language for the educated. Not only did public administrations utilise Latin in their public documents, but knowledge and application of the language was also retained in the educational institutions founded during the medieval centuries. Indeed, maintaining its role as a scholarly language for the exchange of philosophic and technological ideas, the mastery of Latin served as an absolute necessity for young schoolboys.

But neither did the Hellenistic influence of discussion among scholars nor the remnants of the Roman education system (i.e. grammaticus and rhetor) remain extensively within the new institutions, rendering the quality of education significantly degraded. During the Early Medieval Ages, most students from Romance-language speaking regions learned how to read and write in Latin simply by reciting the psalms (Riché, Reference Riché1962, pp. 213–217). Though this arduous process was supported through the implementation of hymns that carried rhythm and melody, it nonetheless altered the fact that the basis of education revolved around memorisation. Similarly, the heavy influence of Christian monasticism during the Middle Ages, for one, enforced the strict hierarchy between instructor and pupil while leaving less room for a discussion-based environment. Children were to remain dutiful to their instructors; as the Celtic and English monks Columban and Bede claimed, ‘A child does not remain angry, he is not spiteful, does not contradict the professors, but receives with confidence what is taught him' (Sofroniou, Reference Sofroniou and Sofroniou2016, p. 114).

Of course, it is not to say that the idea of discussion had completely disappeared from the existing pedagogical tools. Learning had no more ardent supporter than Charlemagne, who came to the Frankish throne in 768 C.E., distressed to find extremely poor standards of Latin prevailing within his administration. He thus ordered that the clergy be educated severely, whether by persuasion or under compulsion. Charlemagne recalled that, in order to interpret the Holy Scriptures, one must have a command of correct language and a fluent knowledge of Latin (Contreni, Reference Contreni2014, p. 101). Scholars from non-Romance language speaking regions, such as Aelfric of Eynsham and Alcuin, additionally revived the English cultural standard by producing beginner's textbooks based on dialogues between students and instructors as well as later distributing such texts to other European regions; one such example included Aelfric's Colloquium, which displays an ongoing conversation between students and teacher written in an unpretentious Latin for beginners while featuring characters like ploughmen, an ox herd, hunters, a fisherman, a birdcatcher, and merchants to better help students immerse Latin into their daily livesFootnote 1. Alcuin's Grammatica similarly offered a Latin dialogue between two boys where one asks the other questions on parts of speech and other grammatical features (Matter, Reference Matter1990, p. 647). Nonetheless, such personal accomplishments often remained menial to the general scope of the medieval intellectual community, as the majority of institutions continued to rely on memorisation of one-sided explanations of texts till the year of rhetorica even until the 16th century.

Figure 1. Morghen, R. (n.d.). Petrarch [Illustration]. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Petrarch#/media/1/454103/16662

Petrarch's Educational Philosophy

Much change in classical norms began to ignite upon the emergence of Petrarch in the 14th century, as his reinforcement of humanist ideals garnered support among the following generation of Renaissance scholars. Aside from the various literary accomplishments of his own writings, Petrarch perhaps deserved more recognition for his contributions to Europe's pedagogical atmosphere: in particular, there was the heavy emphasis on the merits of the dialogical method to a scholar's learning.

Routinely disappointed with the state of scholastic learning and the attitude of contemporary scholars, Petrarch mainly criticised the lack of intellectual curiosity and sentiments of conceit held by the intellectual community. In particular, the Italian scholar's On the Solitary Life reveals his perception of philosophy and classics education, one that Petrarch defines as the passion and search for wisdom:

Though I have always diligently sought for the truth, yet I fear the recesses in which it is hidden, or a certain dullness of mind may have sometimes stood in my way, so that often in my search for the thing I may have been bewildered by false lights. Therefore I have treated these matters not in the spirit of one who lays down the law but as a student and investigator (Petrarch, 1356/Reference Petrarch and Zeitlin1924, p. 312)Footnote 2.

As opposed to considering the ‘search for truth’ or the learning process as a pronouncement of absolute truth, Petrarch acknowledges the limitations of one's own intellect towards attaining wisdom regardless of previous knowledge in the classics. Just as how constant learning and academic inquiry are required on the part of both instructors and pupils, Petrarch appears to consider further conversation, questioning, and investigation as an absolute necessity for scholars with advanced Latin skills.

With this context in mind, Petrarch consequently expressed contempt towards many of his colleagues who adhered to the remnants of Aristotle's teachings—the most revered and studied philosopher in Italian institutions—without question. In his De sui ipsius et multorum ignorantia, Petrarch denounces such sentiments to his colleagues who feel uncomfortable engaging in a collaborative analysis of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: ‘Now I believe that Aristotle was a great man and a polymath. But he was still human and could therefore have been ignorant of some things, or even of many things…I shall go further, if I am allowed, by these men who are greater friends of sects than of the truth’ (Petrarch, 1368/Reference Petrarch and Marsh2004, p. 265)Footnote 3. Given that readers only hear Petrarch's side of the account along with the nature of a satirical piece, one cannot omit the possibility of simple ridicule. Yet Petrarch's focus consists not too much of Aristotle's flaws themselves, but rather the systemic issues within his stubborn, modern followers. Adhering too much to the biased and unquestioned institutional models, they have lost the ability to acquire true knowledge and wisdom, from Petrarch's perspective, through refusal of dialogue. As such, the Italian philosopher envisioned education not in terms of an authoritative figure passing on knowledge to his pupils or colleagues but as a mutual process equally demanding to all parties.

In further shedding light on the significance of the dialectic method, one must not omit Petrarch's peculiar practice of his various letters available to the public. While many critics have considered Petrarch's imaginary letters to ancient figures such as Cicero and Quintilian as well as real-life messages to Valla from a perspective of either genre or literary prowess, perhaps Petrarch's method provided another solution for proper discussion during an era of limited communicative devices. Akin to Seneca's Epistulae ad Lucilium and ancient distance-learning, Petrarch added an additional layer of his own; he held the role of both parties within the letter, an ongoing intellectual conversation between himself and a literary impersonation that was syntactically similar to such deceased authors. As observed by Pierre Hadot, Petrarch essentially engaged in a spiritual exercise that found expression in dialogues and in a general dialogical approach to the task of pursuing wisdom (Hadot, Reference Hadot, Hadot, Davidson and Chase1995, p. 93). In doing so, however, Petrarch explains in his letter to the Abbot of St. Benigno the need for all parties—the writer, respondent, and readers from posterity—to remain engaged to achieve proper learning:

I write to you and others, not because what I have to say touches you nearly, but because there is no one so accessible just now who is at the same time so eager for news, especially about me, and so intelligently interested in strange and mysterious phenomena, and ready to investigate them (Petrarch, 1351/Reference Petrarch and Robinson1898, p. 163).

Petrarch's decision to establish his questions and thoughts in the genre of dialogue was not an act of flattery, but it flowed from an embodiment of his educational philosophy. It more importantly concerns the attitude of the imagined reader, who has to arrive at the text willing to be changed; at the same time, the author or instructor, as opposed to instilling his or her ideas in an authoritative manner, must be knowledgeable and confident enough to transfer one's viewpoint. In short, as Petrarch constantly contemplates and writes in order to intellectually improve himself and those around him, he provides a blueprint for classics scholars to become equally engaged in the subject matter.

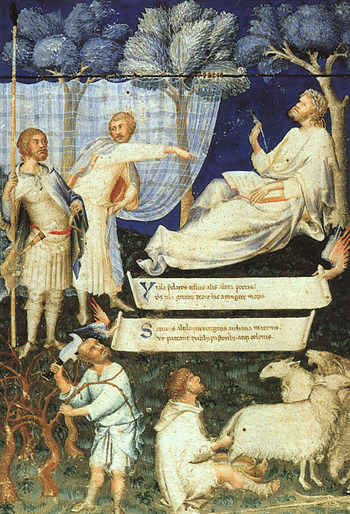

Figure 2. Martini, S. (1340). Allegoria Virgiliana [Illustration]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simone_Martini_-_frontespizio_per_codice_Virgilio_-_Biblioteca_Ambrosiana_-_Milano.jpg

One might ask, ‘So how did Petrarch's firm belief in an all-engaging, dialectic method specifically apply to his own learning of Latin?’ There remains no doubt regarding Petrarch's dedication towards the mastery of the language as a student, for he himself stresses the need for one to ‘love’ and ‘cherish’ the texts with attentiveness (Petrarch, 1351/Reference Petrarch and Robinson1898, p. 240). In doing so, Petrarch underscored the dual significance of commentary worked together with imitation. The Italian scholar particularly saw that reading works by classical authors and subsequently writing imaginary letters in imitation of their linguistic style not only improved one's sheer Latin syntax through practice, but also allowed the scholar to essentially communicate with deceased authors through continuous contemplation of the writings’ structure and hidden meaning within the ancient vocabulary during the writing process. Considering such imitation as another form of internal dialogue, the act of reconstructing the past texts and questioning underlying contexts to fellow intellectuals provided significant insight to him. Petrarch, in fact, utilised the tactic of imitation to a degree previously unimaginable:

[I am] thoroughly absorbed to the works, implanting them not only in my memory but in my marrow…through the process of long usage and continual possession I may adopt them and for some time regard them as my own (Petrarch, 1366/Reference Petrarch and Bernardo1985, pp. XVII-XXIV).

It is clearly not to say that limitations do not exist within the method of imitation. Petrarch himself acknowledged the lack of artistic originality in a work of imitation, and the extent to which an individual other than Petrarch engages in a mutual ‘dialogue’ with the long-gone authors remains questionable. But what matters more to the modern pedagogical methods consists of his attitude in approaching this method. Petrarch clearly appears as a student with particular stress on the process of imitation and internal communication with the author's works; here, he implies that the end product of such imitation entails less value than the road travelled to achieve it, just as how the conclusion of a dialogue remains insignificant in view of the contemplation required. In doing so, Petrarch shared a common sentiment with his Roman predecessor Seneca, who likewise categorised himself as a proficiens as opposed to already having achieved mastery in his letter to Lucilius (Dutmer, Reference Dutmer2020, p. 73).

In terms of understanding the aforementioned method, modern instructors must further acknowledge Petrarch's distinction between imitation and rote duplication of existing texts by means of an educational process, the latter which Petrarch did not support in any manner. Accordingly, Salutati clarified remaining concerns regarding his predecessor's pedagogical method to Leonardo Bruni: ‘Imitation always contains something that is proper to the imitator, and does not entirely belong to the author imitated, whereas copying tends to reproduce in entirety the imitated author’ (Salutati, n.d./Reference Salutati1996, p. 73)Footnote 4. Here, by indicating the qualifications of imitation as a combination of both the author's genuine style and the imitated, Petrarch and his supporters further illuminate the suppositious communication between the two parties. To conclude, Petrarch and Augustine explain the long-term effects that the existing institutional system conveys upon its students in his familiare colloquium: ‘That's what usually happens with students, with the dire and damnable consequence that disgraceful groups of well-read people wander around incapable of translating the art of living into action, even if they are good at it in the schools’ (Petrarch, 1366/Reference Petrarch and Mann2016, p. 135).

Petrarch 's Impact on Future Pedagogy

Petrarch's dialectic method and application to his mastery of Latin, albeit with some remaining scepticism as mentioned, quickly gained support among many educators of the future generation. In particular, the ars dictaminis, the art of letter writing that was frequently practised by Petrarch, became a central feature of 15th century Latin in Italy, where university curricula commonly incorporated the art of composing letters and orations that were then under literary examination by the class. The acknowledgement of Italy's educational supremacy from the Germans soon promoted reform within institutions of Northern Europe as well. Frustrated with the limitations of simple grammar instructions within the classroom, an anonymous German author criticised the long-winded and repeated aspects of Latin grammar that must be removed for older schoolboys:

Italian teachers have this praiseworthy habit with boys whose education is entrusted to them: as soon as they have learned the most elementary grammar they are immediately set to write and discuss on the best poet, Virgil, and the comedies of Terence and Plautus. They study the Epistulae ad familiares, De amicitia, De senectute, Paradoxa Stoicorum and other works by Cicero. This is why they outshine all other nations in writing rich and elegant Latin (Jensen, Reference Jensen1996, p. 67).

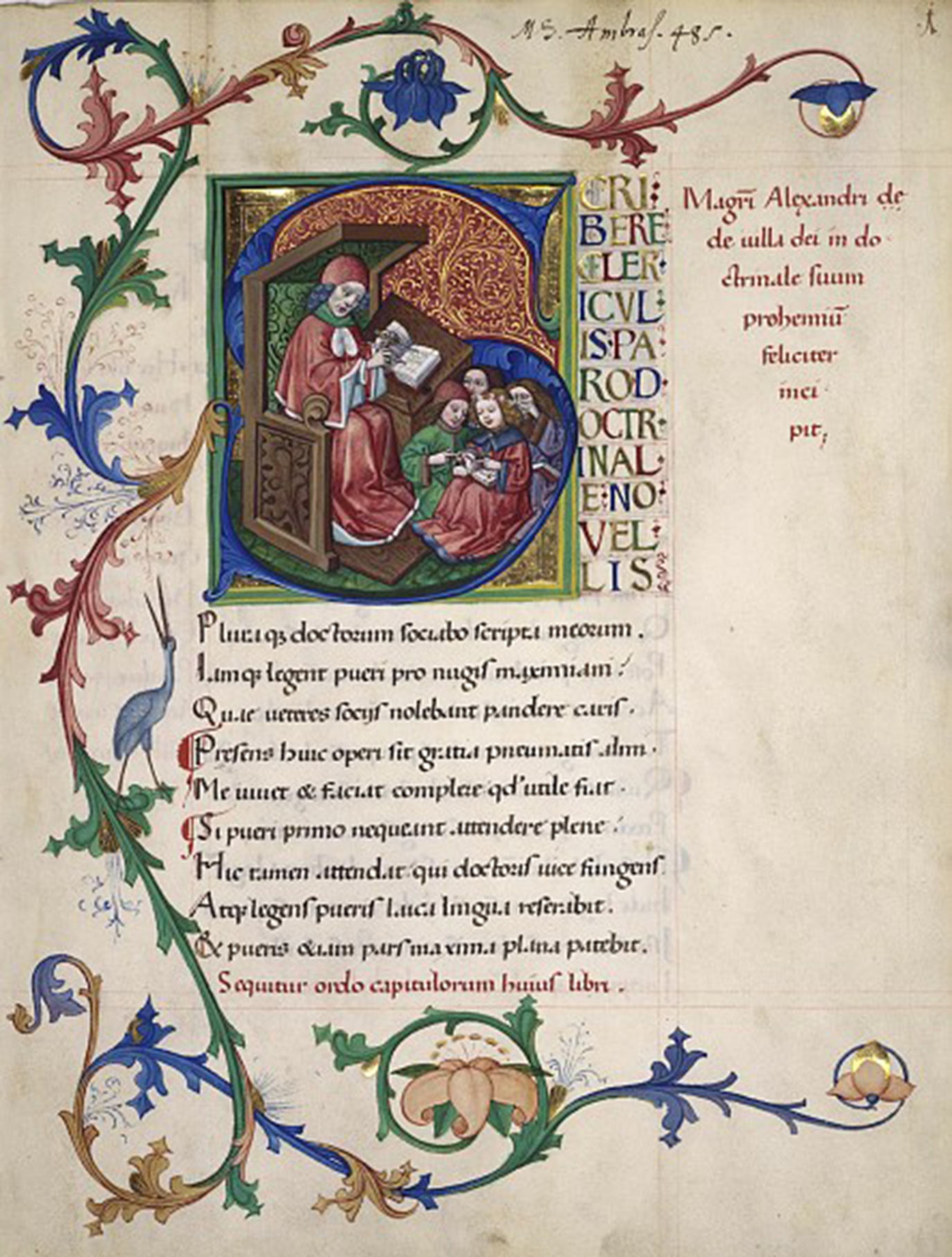

Supported by many scholars, the Doctrinale (1199), a popular grammar textbook by Alexander de Villa Dei, was replaced with the dialectic approach shortly after on account of its poorly phrased explanations and outdated pedagogy; grammar was now a succinct tool used for understanding and enhancing the quality of dialogue, not the central focus in instructing the language (Jensen, Reference Jensen1996, p. 67).

Figure 3. Villedieu, A. von. (1200). Doctrinale puerorum [Illustration]. https://www.habsburger.net/en/media/alexander-von-villedieu-doctrinale-puerorum-page-historiated-initial

As Latin has undergone a certain amount of standardisation along with a more global establishment of adolescent education in the last 200 years, one might claim that certain elements of its pedagogy largely omit such dialogical communication. Since Latin had indeed been considered as a ‘dead language’ due to its relatively small number of fluent speakers and experienced students, the language itself somewhat employed a more sedated, lecture-style environment. However, much of Petrarch's educational spirit continues to cement itself in spirit among prominent school-level institutions, with the Harkness method—a student-led roundtable discussion with minimum intervention from instructors—in United States Preparatory Schools (Grade 7–12) as one specific exampleFootnote 5. Evidently, such forms of the dialectic method, albeit with some technical variations, likewise accentuate the level of equality and participation in intellectual voice as outlined by Petrarch by operating under the premise that every claim deserves discussion of equal weight. When put into practice in Latin classrooms, one instructor found collaborative learning to be beneficial due to ‘the freedom to express personal thoughts and feelings, [for] ownership of the language in this way encourages learners to be actively engaged with the material’ (Nicoulin, Reference Nicoulin2019, p. 94). As further research conducted by Washington University observed that students around grades 7–9 are naturally more argumentative and begin to question authority, the apparent focus on dialogue then cultivates an environment in which students can utilise this freedom in order to dive further into the nuances of the language (Nicoulin, Reference Nicoulin2019, p. 161). Nonetheless, the outlined benefits of Petrarch's dialectic method are no exception for older students as well. Professor Mark Williams of Calvin College, Michigan, duly noted the immediate changes in student learning upon transitioning from memorising a translation previously assigned to sight-reading and discussion question sessions in groups; not only did students demonstrate a much heightened command of the literary devices and context from Augustine's De Civitate Dei, but the process itself also allowed students to most literally engage with the author's motives just as Petrarch found from his letter writings (Williams, Reference Williams1991, p. 259). As such, pushing this dialectic method to the forefront of Latin learning in adolescent age groups reaped benefits in learning, whilst maintaining students’ participation and interest in the language for future years.

Alternatively, other instructors have revived the spirit of Petrarch's ideals through an increased number of ‘full immersion’ Classics courses. One such example may include Fr. Reginald ‘Reggie’ Foster, who ‘at that time the Latin secretary of the Vatican, founded the Aestiva Romae Latinitas in 1985, a free summer school at which he taught a generation of Latinists to read, write and speak Latin’ (Rico, Reference Rico2018, 39). With his earlier students bringing full immersion teaching into the forefront of pedagogy, the classics pedagogical community has perhaps added another method to its arsenal. Familiarising students with the structure of Latin by developing a subconscious network of what ‘sounds’ or ‘feels’ right, this comprehensible method attempts to employ the cognitive processes described by the Concept Mediation Model so that the Latin language possesses an independent mental connection to students (Nicoulin, Reference Nicoulin2019, p. 66). This pedagogical philosophy constantly requires an implicit understanding of the syntax through Latin discussion as Petrarch desired, fostering the improvement of grammar and hidden nuances when learned with traditional instruction as needed (Nicoulin, Reference Nicoulin2019, p. 121). Concerning potential constraints, however, former instructor and librarian Henry Wingate of the Darden School has noted how the success of a full-immersion dialogue heavily depends on the personal abilities of the teacher to speak and lead the discussion in Latin, demanding as much as, if not more, from the teacher as the student (Wingate, Reference Wingate2013, p. 497). Yet just as Petrarch stressed the importance for all scholars to continue engaging in the learning process without satisfaction, a more full-immersion approach should serve as a legitimate opportunity for both students and instructors to hone their Latin skills once more.

The Pandemic Age and Beyond

Though the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic has hindered most institutions from exercising these engaging learning methods in person until most recently, the pedagogy of Classics continued to thrive through online venues as identified by Hunt (Reference Hunt2020, pg. 1). Indeed, thanks to the efforts of innovative classicists, it is now possible for instructors to provide assignments and assessments in line with Petrarch's philosophy of promoting dialogue and process. One quick example may include the recently established Ex Tempore, an online language application where instructors can create assignments with or without a time limit for students to record their responsesFootnote 6. In some venues, the online application caters even more towards the prioritisation of dialogue than the traditional method of assessment; while it is difficult for instructors to comprehend the students’ thought process when asking them to recite a given question regarding a translation or short response in Latin, the app records every moment of the students’ preparation for the question on the screen until the time is up. In doing so, it allows the instructors to prioritise and observe the procedure in which the pupil can adequately build an understanding of the language rather than the sole end product. In turn, the app then allows a continuous chain of video responses from either the instructor or classmates under supervision, allowing the students to stay engaged in a community of intellectually curious scholars. As such, more and more innovations in online technology allow the pedagogical community to consolidate a curriculum revolving an all-embracing engagement.

All in all, this particular observation of Petrarch's methods should not serve as an invective towards the continued instruction of grammar. The Latin language itself, one that is so characterised by its structure or lingua positiva, requires constant review of essential concepts at every stage of a student's learning. Rather, Petrarch's dialectic method offers a viable solution for the issue of an excessively lecture-focused curriculum that subsequently discourages student engagement and brands itself as outdated. As an Aequora volunteer instructor for students (Grades 5–8) from Northern Massachusetts, I myself have faced difficulties in inciting further conversation and intellectual spark with the traditional textbook approachFootnote 7. Hopefully, this piece serves as a helpful historical tool for classics instructors around the world.