Introduction

One out of ten people is believed to be dyslexic (British Dyslexia Association, n.d.). That is on average three students in every language classroom, considering that as per the national curriculum, students are required to learn at least one foreign language at Key Stages 2 and 3 (ages 7–14) (Department for Education, 2013). But which foreign language is most accessible and beneficial for dyslexic learners? An ancient or modern, a transparent or an opaque language?

Research especially in the academic field of Latin and dyslexia is sparse and mostly consists of accounts that are ‘often anecdotal and based largely on teacher's own observations’ (Parker, Reference Parker2013, 7; see also Patterson, Reference Patterson2022). Such literature lacks empirical evidence and an explanation of how the research was undertaken. Concomitantly, the field has relied ‘on findings from more than ten years ago as its main body of evidence’ (Bracke and Bradshaw, Reference Bracke and Bradshaw2020, 13). Claims from such narratives can therefore only present tentative suggestions. Nevertheless, in what follows, a range of literature will be discussed where the authors have argued that access to Latin for young people with dyslexia is beneficial for their language and literacy abilities and inclusive practice generally.

Literature review

Definition and manifestation of dyslexia

Dyslexia is a neuro-developmental condition that affects information-processing and has been defined ‘as a continuum of difficulties in learning to read, write and/or spell’ (Education Scotland, 2020, 6; see also Rose, Reference Rose2009; Thomson, Reference Thomson2013). As a result, not just native language abilities can be impaired but also foreign language learning (Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Ganschow and Pohlman1989, Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Kenneweg and Miller1991, Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Fluharty and Little1995; see also Downey et al., Reference Downey, Snyder and Hill2000; Hill, Reference Hill and Gruber-Miller2006). Laurence (Reference Laurence2010), a dyslexic academic himself, proposed to understand people with dyslexia ‘not so much as disabled, but as neurologically different’ (p. 10), deviating from a ‘deficit model’ of this learning difficulty. It has been stressed that dyslexia does not reflect an individual's intellectual abilities (Education Scotland, 2020; Rose, Reference Rose2009; Thomson, Reference Thomson2013). According to Loud (Reference Loud2011), who related her experience to small group teaching, many ‘extremely intelligent’ individuals with a high ability to function have developed various mechanisms to compensate for their dyslexia so that their problems with language-based information processing only became evident ‘under the extremely rigorous demands of a foreign language class’ (Loud, Reference Loud2011, 48).

Meaning and accessibility of Latin

Latin has been described as a ‘formal’ (Thomson, Reference Thomson2013, 11) and ‘logical, almost mathematical’ (Bracke and Bradshaw, Reference Bracke and Bradshaw2020, 3) language with exemplary phonemic orthography (Coulmas, Reference Coulmas1989). Accordingly, Latin has been considered as transparent with clear letter-sound correspondence and fewer irregularities in pronunciation and spelling than some more opaque modern languages (Hill, Reference Hill2009; Toffalini et al., Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019). For instance, the French je peux (I can), elle peut (she can), un peu (a little) are all pronounced the same, whereas in Latin possum (I can), potest (she can), paulum (a little) may look similar but are consistently pronounced as they are spelt. Such attributes can make Latin particularly accessible for learners with phonological processing deficits. Although it influenced the development of the modern Romance languages, nowadays Latin has no longer any native speakers.

With Latin as a ‘dead’ language, students are usually only expected to translate and analyse Latin texts; speaking or writing in Latin is not required and neither pronunciation nor spelling is assessed. On that account, Latin examinations might be more manageable for dyslexics than examinations in other transparent languages, like Spanish. Toffalini et al. (Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019) suggested that students with dyslexia benefit from the limited orality and only written exposure to Latin (see also Ashe, Reference Ashe and Lafleur1998; Dinklage, Reference Dinklage1971; Hill, Reference Hill2009; Parker, Reference Parker2013). As one of the few in the academic field, Toffalini et al. (Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019) undertook quantitative research with a between-subject design. Their participants were 36 Italian secondary grammar school pupils, 27 of whom were females, between 14 and 20 years old and with a formal diagnosis of dyslexia. The control group consisted of 36 typical readers matched on age and gender. In individual sessions reading decoding speed was measured and Latin grammar was tested. Effect sizes for power calculations showed the magnitude of the difference between groups; the validity of the measure was ensured by utilising a Latin grammar test that was tried and tested; the test-retest reliability was good. It was found that students with dyslexia, despite performing significantly worse than the control group in reading Latin, showed less severe difficulties in Latin grammar tests. Findings, however, cannot automatically be applied to any context, since they were dependent on the participants' mixed-age groups, the particular tasks they had to complete, and the combination of Italian as a first and Latin as a second language. Yet, similar findings for the combination of English and Latin have been supported by Ashe (Reference Ashe and Lafleur1998) and Sparks et al. (Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Fluharty and Little1995) who contended that explicitly teaching Latin grammar was beneficial for dyslexic learners. Shahabudin and Turner (Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009), who drew on their personal experiences as study advisers with backgrounds in Classics teaching and educational psychology, argued that ‘the inflected nature of ancient languages can operate either in favour or against’ learners with dyslexia, recognising both the constraining and enabling functions of Latin grammar (Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009, 11). Given the diverse underlying causes and associated difficulties regarding linguistic processes present in dyslexia (Rose, Reference Rose2009) this was perhaps not surprising.

It is worth noting that as part of the multi-disciplinary nature of classics, Latin is not just a linguistical subject, but its curriculum may also consist of ancient culture, art, social, military, and political history, religion, and mythology (Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009; see also Deacy, Reference Deacy2015; Hubbard, Reference Hubbard and Morwood2003). Such a curriculum lends itself to the usage of visual clues, like inscriptions (Laurence, Reference Laurence2010), pictures and ancient artefacts, thus making learning easier for students with dyslexia (Thomson, Reference Thomson2013).

To date, empirical research has not yet examined the objective achievements of secondary students with dyslexia in Latin when compared to modern languages, whilst exploring individual accomplishments, enjoyment, interests, and the value of learning Latin, French, or Spanish. The current research is designed to explore the experiences of dyslexics learning these languages, and to examine the relationships between dyslexia and examination results in Latin, French, and Spanish in two ways; first, through semi-structured interviews, and second, through national and international exam grades, using a mixed-methods approach.

Research questions and hypotheses

This project has two key research questions, which will be explored qualitatively, and three key hypotheses, tested quantitatively:

Qualitative:

(1) What is the experience of students with dyslexia learning Latin?

(2) What is the experience of students with dyslexia learning a modern foreign language, like French or Spanish?

Quantitative:

(3) There will be no significant association between dyslexia in secondary students and their examination results in Latin.

(4) There will be a significant association between dyslexia in secondary students and their examination results in French.

(5) There will be a significant association between dyslexia in secondary students and their examination results in Spanish.

Methodology

A mixed-methods design provided insight into the unique experiences as well as a numerical representation of the achievements of secondary students with dyslexia studying Latin or a modern foreign language. Combining elements of qualitative and quantitative research gave a more complete picture of the research issue with both depth and breadth. For the qualitative component, a pragmatic position to determine what was useful for this study was adopted. As in the study of Parker (Reference Parker2013), a semi-structured interview approach was implemented which facilitated conversations with the participants using various open-ended questions. The researcher was able to react to what was said and focus on relevant context. For the quantitative component, a quasi-experimental, between subject-design was used, with results from national and international exams in Latin, French, and Spanish, including GCSEFootnote 1 and International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IB),Footnote 2 as the dependent (DV1 = low exam grades, DV2 = high exam grades) and the condition of dyslexia as the independent variable (IV1 = dyslexic, IV2 = non-dyslexic). The associations between these categorical variables were evaluated.

Participants

For the semi-structured interviews, participants were one current and six former female secondary students, aged between 16 and 29. Six had a formal diagnosis of dyslexia, one exhibited traits of it. Three had learnt French and Spanish, two Latin and Spanish, one Spanish, and one Latin, French, and Spanish mostly at secondary school. They had attended school or university in the UK and were native or near-native speakers of English. All identifying details have been anonymised and names have been changed.

For the survey of examination results, anonymous, non-personal data were collected from one Swiss selective grammar school, offering the IB, and one Scottish independent school, offering the IB as well as GCSEs. From 2018 to 2022, the Swiss school had 43 students taking IB Latin, four of whom had been formally diagnosed with dyslexia. From 2018 to 2022, the British school had 57 students taking GCSE Latin, six of whom had (traits of) dyslexia; 122 students taking GCSE French, 15 of whom had (traits of) dyslexia; 80 taking GCSE Spanish, 15 of whom had (traits of) dyslexia. In 2023, the British school had six students taking IB Latin, none of whom had (traits of) dyslexia; 13 doing IB French, one of whom had traits of dyslexia; 23 doing Spanish, five of whom had (traits of) dyslexia. In addition, five exam results (two for Latin, one for French, and two for Spanish) from three of the interview participants were used for quantitative analysis. 30 unofficial National 5Footnote 3 results for Latin from a Scottish state school had to be removed since there were no equivalent data for modern foreign languages. After data clearing, 349 examination grades were gathered in total, with 51 of the grades from students with at least traits of dyslexia.

Participants and participating schools were recruited using purposive sampling. An approach letter with a request to provide examination results for Latin, French, and Spanish and a link to a Qualtrics® form, containing all the relevant information about the interviews as well as the consent process for participants and guardians, were sent out via email to headteachers and language teachers in the researcher's network. Both the letter and the form were also circulated through various channels, including Classics for All, The Classical Association, The Association for Latin Teaching (ARLT), The Classics Library, Dyslexia Scotland, IB Community Forum, and The Student Room. In addition, the language departments of two universities agreed to forward the request to relevant students and teachers. The examination boards International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO), Oxford, Cambridge and RSA Examinations (OCR), and Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) were also approached in order to obtain data for the comparison of Latin and modern language results for dyslexic and non-dyslexic students. However, they did not store the information on special educational needs, so it was necessary to collect the data from individual schools.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations involved in the data collection were based on the four core principles of respect, competence, responsibility, and integrity, as stated by the British Psychological Society (2021). Privacy and confidentiality were maintained by collecting data without obtaining any personal, identifying information in the case of the examination results, and, in the case of the interviews, by replacing participant names with codes.

For the semi-structured interviews, the researcher was sensitive to the issue of balance of power. Participants received an information form and a debrief sheet and written and verbal consent to participate was sought. In outlining the details of the study, the voluntary nature of participation in the study was emphasised and it was stated that participants were free to withdraw at any point. For the collection of examination results, headteachers and teachers as gatekeepers were asked for permission to access relevant anonymised, non-personal examination data.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from reviewers in the UCL IOE Department of Psychology and Human Development. There was no conflict of interest.

Materials

To investigate the experiences of secondary students learning Latin or a modern foreign language, semi-structured interviews were conducted that included the following questions:

What motivated you to learn Latin, French, or Spanish?

How did you learn that language? What methods or strategies proved to be useful for you?

Overall, how accessible did you find Latin/French/Spanish for someone with dyslexia? And what were the challenges and barriers?

To what extent did learning that language benefit you?

Prompts were used to clarify questions, check for understanding, and ask for more information, e.g. ‘Can you just very briefly explain to me what that is again?’. A pilot interview conducted with another educational professional indicated that the questions covered the issues of interest and were unambiguous.

Other materials included an approach letter to headteachers and language teachers, a Qualtrics® form for participants and guardians with all relevant information as well as the consent process pertaining to the study, and a debrief sheet. Datasets of exam results were collected on an Excel® master spreadsheet.

Procedure

The initial stages involved contacting 30 language teachers and 15 headteachers asking for their permission to access public examination results for Latin, French, or Spanish. Those who responded were also asked to share the link with the information sheet and the consent form for the interviews. Additionally, the request for participants and participating schools was circulated through the networks outlined in the Participants section.

The interviews were conducted using Zoom® with a UCL account and voice recording only. Participant consent forms were filled in on Qualtrics® in advance of each interview. At the outset of the Zoom® session, verbal consent to participate was sought. Participants were then asked questions about their background, experience as secondary students with dyslexia and their experience learning Latin or a modern foreign language. The interviews lasted between 20 and 36 minutes. Once they were fully transcribed, the recordings were deleted.

Data analysis

The responses from the interviews were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). This process required manually editing the interview transcripts that were generated using Microsoft® Word so that the researcher could familiarise herself with the data. Next, initial codes/nodes and sub-codes/sub-nodes were created and applied using the qualitative analysis software NVivo®. Finally, codes were reviewed and refined by expanding, collapsing, and renaming them. Coding was semantic, capturing the explicit rather than the latent meaning of the data. Due to the subjective nature of the research questions, codes could not be determined in advance but were generated by the researcher (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012), so the dataset was analysed inductively.

To compare the examination results of dyslexic and non-dyslexic students, the statistical software package SPSS® was used. Three chi-square tests were conducted, one each for Latin, French, and Spanish examination grades. Cross tabulations were also used to analyse the scores.

Results

Semi-structured interviews

Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed seven themes concerning the experience of learning languages as secondary students with dyslexia, depicted in Figure 1. Furthermore, most themes were split into two categories: Latin and modern foreign languages. Three sub-themes were identified for accessibility, 12 for benefits, 11 for challenges and barriers, 16 for methods and strategies, and one for strengths. The sub-themes logic (accessibility); confidence, English grammar, English vocabulary, language learning (benefits); grammar, multi-sensory, support, and vocabulary (methods and strategies) appeared in both language-categories. It was found that the students' responses indicated similar sub-themes when talking about their experiences in Latin as compared to when talking about French or Spanish. (English) grammar was not only present across both language-categories but also in several themes. The themes challenges and barriers and strengths were not split into language-categories since the sub-themes described perceptions applicable to various learning environments. What differed between Latin and modern foreign languages was the content of the themes class size and motivation as the participants' narratives focussed on the intimate nature of Latin courses on the one hand, and the value of communication in modern language classes on the other hand. Besides, general, non-language-specific experiences of the students with dyslexia were recorded. (For the full table with sub-themes see Supplementary Appendix 1).

Figure 1. Main themes on the experiences learning languages with dyslexia derived from the semi-structured interviews.

The theme accessibility explored whether students with a learning difficulty like dyslexia would find the language in question easy to acquire. Benefits dealt with the positive effects of learning that language as perceived by the participants. Challenges and barriers concerned the reasons that made language learning more difficult for participants. Class size referred to the number of students in the language classrooms. Methods and strategies addressed various ways of successfully learning the language. Finally, motivation focused on why the students had a desire to learn Latin, French, or Spanish.

Overall, many themes and sub-themes revolved around how and why languages were taught and learnt. Whether or not students with dyslexia enjoyed and succeeded in learning Latin, French, and Spanish was very often dependent on the methods and strategies and the support they received. Problems memorising and processing information made language learning generally difficult, whereas speaking came naturally to students with dyslexia.

Survey of examination results

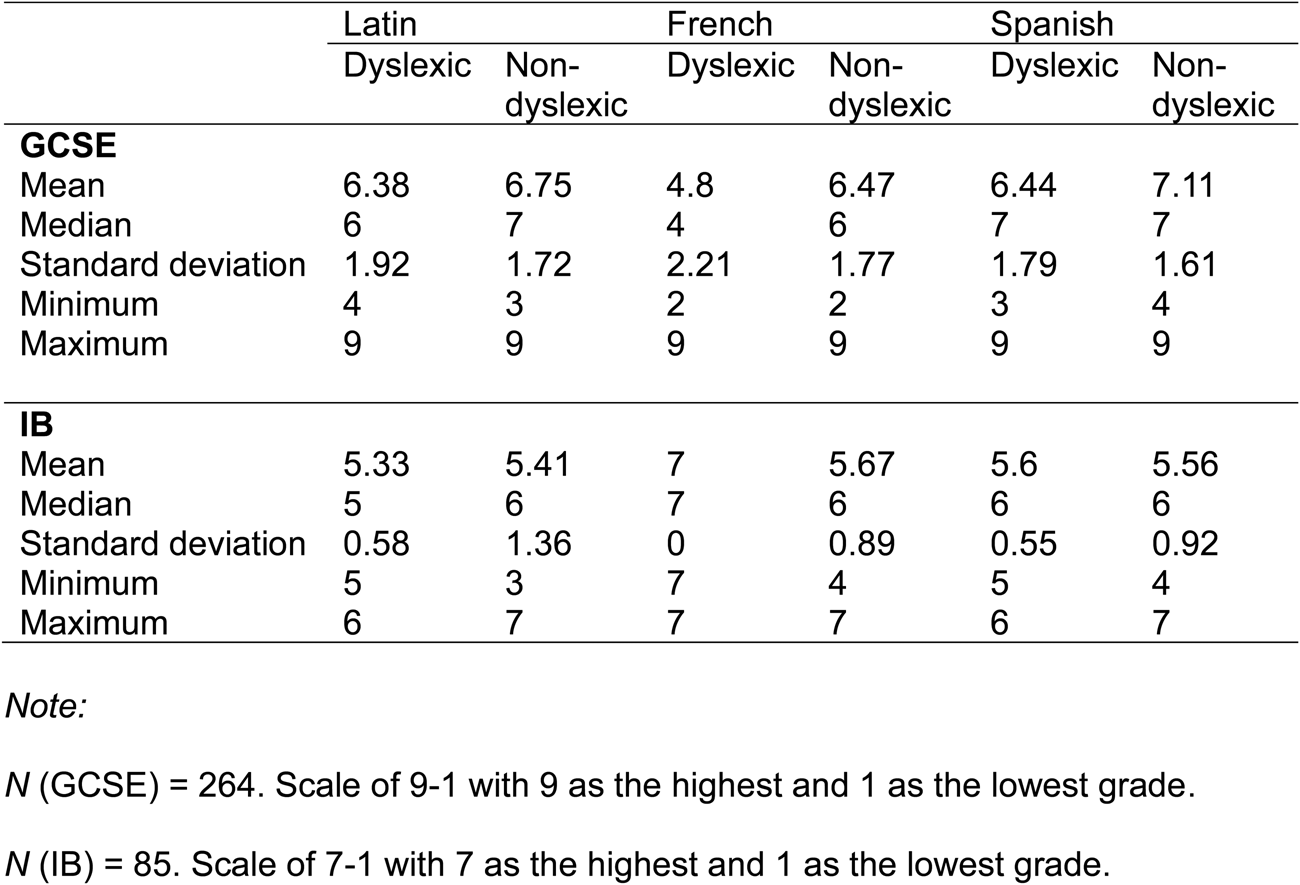

The quantitative component of this study aimed to investigate the associations between the condition of dyslexia in secondary students and examination results in Latin, French, and Spanish. After data cleaning, there were 349 GCSE and IB results, 108 for Latin, 136 for French, and 105 for Spanish. The descriptive statistics for the GCSE and IB scores can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Descriptive statistics from the survey for GCSE and IB exam grades for dyslexic and non-dyslexic students.

Mean scores, histograms, and cross tabulations indicated that the disparity of examination results between dyslexic and non-dyslexic students was particularly high for French.

Since the data were categorical scores, chi-squared analysis was used to see whether the distribution of low and high scores for Latin, French, and Spanish was different for the dyslexic and non-dyslexic groups. The initial prediction was that for Latin the distribution should not be different for the dyslexic and non-dyslexic students, while for French and Spanish, the distribution should be different, with higher grades more numerous for non-dyslexic students. For awards with a 9-1 scale, the data was coded as high exam grades = 9-6 and low exam grades = 5-1. For awards with a 7-1 scale, the data was coded as high exam grades = 7-5 and low exam grades = 4-1.

The adjusted residuals for exam grades in French of 2.8 (dyslexic – low grades), −2.8 (dyslexic – high grades), −2.8 (non-dyslexic – low grades), and 2.8 (non-dyslexic – high grades) indicated that the number of cases in all these cells was significantly larger or smaller than would be expected if there were no association between dyslexia and examination results in French.

The calculated chi-square showed no significant associations between dyslexia and examination results in Latin, χ2(1) = 0.32, p = 0.57 or p > 0.05, φc = 0.05,Footnote 4 and Spanish χ2(1) = 0.92, p = 0.34 or p > 0.05, φc = 0.09.Footnote 5 For French, however, there was a statistically significant association between secondary students with dyslexia and lower exam grades, χ2(1) = 8.1, p = 0.004 or p < 0.01, φc = 0.24, since χ2 was greater than the critical value of 6.63. Therefore, hypotheses (3) and (4) were confirmed while hypothesis (5) was rejected.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the experiences of secondary students with dyslexia learning Latin, French, or Spanish, and to examine the relationships between dyslexia and achievements in public examinations in Latin, French, and Spanish.

Reflexive thematic analysis of the interviews revealed seven main themes: accessibility, benefits, challenges and barriers, class size, methods and strategies, motivation, and strengths. The findings showed that a positive learning experience was less dependent on which language the students learnt, but rather on the teaching method and whether support was available. In many cases, dyslexic learners felt more supported in Latin and also in Spanish simply because classes were smaller than in French. Reduced class sizes might have also led to better learning experiences in general, as another participant commented on the positive atmosphere of her Spanish class (Supplementary Appendix 1). A multi-sensory, active approach to Latin, or rather a multi-sensory, interactive, immersive approach to French and Spanish, has been depicted as most effective. In a modern language classroom, communicating was consistently seen as motivational (Supplementary Appendix 1). In an ancient-language classroom, however, an emphasis on orality had its pros and cons depending on individual preferences and circumstances (Supplementary Appendix 1; see also Toffalini et al., Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019). Similarly, grammar teaching played both an inhibiting as well as a facilitating role for different participants (see also Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009). Remarkably, not just Latin but also French and Spanish were perceived as having a positive effect on English native language skills and foreign language learning in dyslexic learners (cf. Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Fluharty and Little1995); nonetheless, Latin might have improved English writing skills more than modern languages did had it been assessed (Supplementary Appendix 1). A conceivable explanation for this is that Latin – as part of the multi-disciplinary nature of Classics (Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009) – requires more structured essay writing in English. Another benefit was the sense of accomplishment students with dyslexia gained when learning Latin, French, or Spanish (Supplementary Appendix 1). In general, students with dyslexia were good at speaking in class but struggled with memorising and processing information (Supplementary Appendix 1). Yet, games, rhymes, songs, organisation and categorisation of learning material in Latin, French, and Spanish seemed to aid poor working memory, something that has also been noted in the literature (e.g. Hill, Reference Hill2009; Loud, Reference Loud2011; Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009).

Regarding the survey data, chi-square tests were used to investigate whether dyslexia status was associated with a rate of higher or lower grades in secondary school public examinations in Latin, French, and Spanish. Results revealed no significant association for Latin or Spanish, but a significant association between dyslexia and examination results in French. Overall, students with dyslexia achieved grades that were comparable to those of their non-dyslexic peers in Latin and Spanish but did much worse in French. Smaller classes in Latin and Spanish resulting in more individualised support, better classroom interaction, and a more effective teaching approach, together with a better accessibility of transparent languages could have all been possible reasons why students with dyslexia did better in Latin and Spanish. Initially, it was hypothesised that despite the transparency of both languages, students with dyslexia would achieve better examination results in Latin than in Spanish, since speaking or writing in Latin is not required and pronunciation or spelling not assessed. However, higher examination results of dyslexic learners were not dependent on the limited orality of a ‘dead’ language alone (cf. Toffalini et al., Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019) which is why hypothesis (5) was refuted.

In sum, whereas positive learning experiences for students with dyslexia hinged on the appropriate teaching method and the perceived support rather than the language per se, higher examination achievements were also dependent on the level of orthographic transparency but not on the degree of orality of the language learnt.

These findings supported previous research claiming that small group teaching (Ancona, Reference Ancona1982; Hill, Reference Hill2009), an open dialogue between students and their teacher (Hill, Reference Hill and Gruber-Miller2006, Reference Hill2009; Patterson, Reference Patterson2022), and a teaching approach that is modified (Downey et al., Reference Downey, Snyder and Hill2000; Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Fluharty and Little1995), multi-sensory (Ancona, Reference Ancona1982; Hill, Reference Hill and Gruber-Miller2006, Reference Hill2009; Hubbard, Reference Hubbard and Morwood2003; Loud, Reference Loud2011; Shahabudin and Turner, Reference Shahabudin and Turner2009; Sparks et al., Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Kenneweg and Miller1991, Reference Sparks, Ganschow, Fluharty and Little1995; Thomson, Reference Thomson2013), or active (Patterson, Reference Patterson2022) can lead to success in students with dyslexia. They were also in line with preceding research which considered transparent languages with regular pronunciation and spelling like Latin – and for that matter also Spanish – as more accessible for dyslexic learners (Hill, Reference Hill2009; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Macaro, Alba and Cipolla2015; Toffalini et al., Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019). Additionally, high achievements of secondary students with dyslexia, particularly in Latin, have been accounted for in the pre-existing literature (Parker, Reference Parker2013; Toffalini et al., Reference Toffalini, Losito, Zamperlin and Cornoldi2019).

To advance empirical research in the academic field of Latin and dyslexia, one aim of this study was to investigate both the subjective experiences and the objective examination results of secondary students with dyslexia learning Latin and compare them with those in French and Spanish. Accordingly, a quantitative and a qualitative approach were combined. The results of this study indicated that Latin and Spanish as transparent languages were more accessible and beneficial than French. These outcomes argue for improved access, especially to Latin, for dyslexic learners and emphasise the significance of inclusive practice in any language classroom. In such classrooms, dyslexia is not so much seen as a deficit but rather as an individual difference (see Laurence, Reference Laurence2010). These findings also imply that students with dyslexia should be encouraged to choose at least one transparent language at school not only to fulfil a requirement but also to improve their language and literacy abilities.

Limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the relatively small number of examination results of dyslexic students in Latin and Spanish might have impacted the external and internal validity of the study. Thus, the sample might have not adequately represented the broader population from which it was drawn and been more susceptible to random variations or selection bias. Further research with a higher proportion of dyslexic students learning Latin and Spanish is required to confirm these results. Second, since the interview participants were all female, the study could neither assess the influence of gender nor provide insights into the male perspective. Third, the sample for the survey was drawn from a grammar and an independent school and the majority of the interviewees were from rather privileged and WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) backgrounds, thus lacking diversity in terms of socioeconomic status, culture, and education. Fourth, findings are limited to students who learnt English as their first language; cross-cultural studies that explore the impact of Latin on other native languages are warranted. Fifth, findings are limited to secondary students with dyslexia; future research in the field should explore the experiences and achievements of students at different educational stages and with different learning difficulties doing Latin. Finally, it should be noted that the researcher was a Latin teacher herself at the same Scottish independent school the sample was taken from which could have influenced the objectivity of the study. In general, more up-to-date research with empirical evidence from larger samples is needed in the academic field of Latin and educational psychology. Given that the overall uptake of Latin was 1.6% of GCSE students in 2019 (Gawedzka and Gill, Reference Gawedzka and Gill2022), the small number of young people learning Latin these days – with an even smaller number of students with learning difficulties – will always make it challenging to obtain a sample size large enough to lead to meaningful and representative effects.

Conclusion

Addressing a gap in the literature, the study has provided insights into fostering positive, beneficial experiences for secondary students with dyslexia learning Latin, French, or Spanish. When it comes to achieving higher examination results, results of this study have suggested that languages with transparent orthographies – may they be ancient or modern – are more accessible than opaque languages for students with dyslexia. These findings should encourage Latin and modern language teachers to create inclusive classrooms and encourage students with dyslexia to not shy away from choosing Latin.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2058631024000138.