The following article is made up of several assignments set for the Cambridge PGCE secondary teacher training course on the subject of the telling of a mythological story to a key stage 3 class of students aged around 11–14 years. The setting of the assignment arose out of discussion with mentors from the PGCE partnership for Classics teacher trainees in response to the following three requirements:

1) To include a lesson in their first school placement which fitted well within any of the timetabled lessons from the wide range of schools which participate;

2) To provide an opportunity to encourage trainee teachers at an early stage in their school placement to practise and reflect upon their own oracy as a medium for teaching and learning; and

3) To provide an opportunity to think about research methodology on a small scale ahead of the major research assignment of the second school placement.

Trainees were encouraged to tell a mythological story to the class, lasting about ten minutes. They could use props and other visual aids if they wished, but the emphasis was for them to practise speaking before the class, using prompt cards if necessary, and employing all the techniques of a professional oral ‘poet’ – such as gesture, eye contact, tone of voice and so on. There is obviously considerable general interest among younger students about mythology. Locally, interest is captured by the Cambridge School Classics project which puts on an annual Ovid Mythology competition and the website War with Troy is used by several of the schools where trainees are placed. Its use as a stimulus for learning has been well-documented by its author and past PGCE subject lecturer Bob Lister (Reference Lister2005, Reference Lister2007) and by Walker (Reference Walker2018), a former teacher trainee from the faculty. Some of the Latin textbooks such as Minimus (Bell, Reference Bell1999) and Suburani (Hands-Up Education, 2020) contain myth episodes and are familiar to the teacher trainees. The GCSE and A Level qualifications often contain mythological subject matter. Khan-Evans (Reference Khan-Evans, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) has shown how older students of Classics have retained deep-rooted affection for mythological stories in their earlier schooldays. Research into the power of mythological storytelling as a stimulus for learning, creative arts and even therapy is current, as the Our Mythical Childhood project (2020) has demonstrated. A book of the project's work is eagerly anticipated next year. The recent Troy exhibition at the British Museum has also awoken considerable interest.

The following accounts are by the teacher trainees themselves. They reveal some of their tentative efforts to engage with storytelling with classes of students with whom they were not especially familiar. They show, I think, considerable bravery in exposing their own shortcomings, overcoming the challenges and situating their own developing understanding of what it is to teach, to listen and to learn almost alongside their classroom students. Some use props and slideshows, prompt cards and bits and pieces to give themselves almost something physical to grasp and to hold on to – a secure place in an otherwise uncontrolled one. Others are more comfortable just telling the tale (transcripts are those made after the event). While this article is very long and perhaps might seem indulgent, I think that there's much to learn here about how trainee teachers set about their task and explore and reflect upon their experiences, and the recorded examples of lessons afford, I think, an interesting glimpse into teacher and student talk in the Classics classroom. Some trainees self-define as teacher, others as storyteller; some set work based on the telling of the myth, others are happy to use the story as a basis for discussion or creative activity. Several express surprise and satisfaction at the attentiveness of students in listening to lengthy stories, at their ability to recall details from them, and to be able to reactivate prior knowledge. Transcripts suggest student engagement levels are high. It is worthwhile considering how much more the students might want to ask questions when they have listened to a storytelling compared to when they are answering questions set for them on a worksheet.

The teacher trainees gave permission for their assignments to be included. In the spirit of narrative research, they are presented ‘as they are’ without editing by myself, except for typographical standardisation.

The value of storytelling in education should not be underestimated. Bage lists twenty reasons why stories support educational practice, for example: stories prioritise meaning; students enjoy stories; stories inspire curiosity; stories are important in developing literacy (Bage, Reference Bage1999, p. 30–32). Storytelling also has considerable importance for teaching oracy, the ability to express oneself fluently in speech. Although oracy is an important life skill, as the English Speaking Union's Speaking Frankly pamphlet (ESU, n.d.) explains, it is not simply talking, but it is also the ability to imagine, to receive and build upon answers, to analyse and evaluate ideas and problems, and it is important to well-being. However, it currently has no formal place in the curriculum. As Mercer et al. (Reference Mercer, Ahmed and Warwick2014) highlight, oracy is actually discouraged by a mentality that equates talking with not learning. The ESU website also cites a study by the Better Communication Research Programme that revealed that students with good communication skills are four times more likely to get five A*-Cs at GCSE (ESU, 2019). Storytelling in secondary education can develop both discussion and literacy skills, as Walker (2014) concludes in her small study of the impact of storytelling in Classics lessons.

I decided to undertake my storytelling in a Year 7 Ancient History lesson because the topic for the class, the Trojan War, provided a suitable opportunity for storytelling within the existing scheme of work. My placement school, an academically non-selective single-sex girls’ academy in Hertfordshire, rotates the Year 7s through a carousel of Ancient History, Latin and two other optional subjects. My lesson, just after the carousel rotation, was the students’ first Ancient History lesson. The Trojan War course is designed around the Cambridge Schools Classics Project's War with Troy (Classical Tales, 2020) an oral narrative based on Homer's Iliad and broader narratives about the Trojan War. Reedy and Lister describe the narrative as designed to ‘develop literacy skills, particularly speaking and listening’ (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007, p.3). I was teaching a lesson based around Episode 1.

I chose to narrate the wedding of Peleus and Thetis because I thought that this narrative would provide interesting discussion material. During my observations of Year 7 lessons in the previous carousel rotation, I noticed that the teacher and the students often discussed the far-reaching consequences of characters’ decisions and how responsible individual characters were in the events that followed. I wanted the students to begin to consider these questions early on in the story, where they could imagine the potential outcomes. I based my storytelling around the content of the War with Troy recording, so that the students could access the information they would reflect on in later lessons. I also made additions to focus on the decisions of various characters during the narrative. I aimed to encourage the students to consider consequences and different perspectives.

I decided to follow my storytelling with a hot seating activity to achieve this aim. I drew on feedback from student interviews with Year 7s during a school-based Professional Studies session on Teaching and Learning. The interviews suggested that Year 7s felt they learned best when activities were creative e.g. story-writing or hands-on, such as took place in Science practical lessons or drama activities. Before the lesson I distributed characters’ names onto the students’ desks, ensuring that each group of four contained a variety of perspectives. The students then pretended to be this character during the activity and hot-seated each other about their characters’ actions and views. I also put a series of prompt questions on the board to aid the students. During the activity, I assessed the students’ learning through observation and obtained student responses to my storytelling. The students also had a matching-up activity to complete while listening to the story. I initially planned for them to do this after the story, but it became apparent in the lesson that some students struggled to recall details. The matching-activity also allowed me to assess that most students were listening and following, at least, a part of the story.

However, the hot seating activity had limitations as a means to assess student learning and gain student feedback on my storytelling. First, there was little to no written evidence and my assessment relied on my own observations. However, the seating arrangement meant that some groups were less accessible, so I did not observe the groups evenly, nor could I observe one group for any length of time, which limited my ability to assess the students’ learning. Some of the groups had questions or needed additional support. In addition, this was the students’ first experience of a hot seating activity and I should have explained the activity more, since two groups seemed to have not understood – one group played ‘Who am I?’. I also discovered that a number of the students struggled to recall characters’ names, especially Hera and Peleus. This seemed to be more of an issue with associating names and characters, as the students readily discussed ‘the evil one’ (Eris), ‘the goddess of love’ (Aphrodite), ‘the stupid one’ (Zeus). I tried to help the students by listing the characters on the board, using key words to describe each. Despite the issue, the student descriptions of Eris and Zeus indicate that the students were forming opinions about the characters.

I attempted to acquire feedback on my storytelling through observing the students and asking them questions. However, I often felt that I was interrupting the students’ activity by asking questions. I also discovered that the students were hesitant about saying what they thought about the storytelling and often gave vague or monosyllabic answers which required further questions. If I tried to get feedback in this manner again, I would plan my questions to a greater extent to encourage student response. This was also the students’ first lesson with me and they were likely more guarded as a result.

Regardless, both the student feedback and the recording revealed interesting aspects of my storytelling. Student feedback generally focused on the props, and the ‘emotion’, which made it more exciting. My props included a plush heart, a plush owl and a tiara to represent the three main goddesses, a pair of scissors for the fates and a golden apple. The props which sparked the greatest interest were the golden apple and the heart. I revealed the apple, when Peleus discovered the apple in the story. Meanwhile the heart was used as a visual representation of Aphrodite. However, other props were less effective; it did not seem like many students noticed the scissors. The owl was also difficult for students to see at the back, although it and the heart elicited greater student interest and recall of material than the tiara. My use of props was also concentrated towards the end of the story and quite limited. Although not mentioned in the student feedback, I wonder if a greater use of props might have aided the students who found recall harder.

From what I could establish, the students generally enjoyed the storytelling itself. Some of my feedback revealed that the students preferred the story being read aloud because it was more exciting and there was more emotion. As far as I could establish, a considerable number of students were also able to recall the story in detail. However, when I listened to the recording, I felt that my storytelling was often not as effective as it could have been, particularly in the early part of the story. I sometimes muddle words (e.g. ‘lightfully’ instead of ‘lightly’) and phrases when speaking causing my syntax to be slightly confusing. I decided to read off a script, which was a mistake because I know from experience that I speak better without a script as I tend to fixate on it. After a slightly stilted start, the pace became more settled, if a little fast at points. My pace and tone were varied the most in the later part of story when I varied pitch and volume to create tension and excitement as Eris entered the story and decided to drop her ‘gift’. I used deliberate pauses, a faster pace and dropped my volume slightly as Eris was first mentioned and during her plans. The fastest part of the storytelling was when the apple fell, and I tried to mimic the speed of it gaining momentum then the sudden silence that followed its arrival.

In addition, I naturally gesticulate when talking, and I found that my hands tended to move quite randomly when I wasn't deliberately using them for parts of the story. My uses of gesture mainly focused around gestures to reflect the actions of characters, e.g. holding out a hand, thinking, or the falling apple. I also tried to ‘act’ the characters during the final section to give an impression of the different gods and goddesses. The part of the narrative with Eris and the argument was the part described as having lots of ‘emotion’ by one of the students.

The storytelling did function to achieve my aims to some extent. Most of the groups engaged well during the hot-seating activity and some began not only to really get into character and consider their character's views but also imagining quite significant follow-ups to the story such as Zeus eventually getting so frustrated that he would banish the goddesses or that the apple situation would be resolved or cause an assortment of further problems. Even the group playing ‘Who am I?’ still discussed the characters in detail. Perhaps discussion and student talk could have been further encouraged through an extended activity or by giving the students their own props to allow them to explore acting out parts of the narrative. One group did not engage in discussion preferring to write answers to the prompts; even they engaged with the story to some degree and they also participated in the brief whole class discussion at the end of the lesson.

While the storytelling did lead to an interesting activity, its effectiveness is debatable. Could the same effect have been achieved without oral storytelling? The answer is probably, but perhaps not as readily or as quickly. In contrast, I observed that a Year 9 class, which I taught for a sequence of lessons, took longer to engage with a written text than a spoken text, particularly if they are weaker readers and reading can be hindered by not understanding words. Oral storytelling has the advantage that it is immediately accessible to these students. In addition, as my students remarked, the excitement of the story makes it more enjoyable and in turn leads to their increased engagement. As Bage argued, the value of stories in teaching history was that it is a medium that students enjoy and engage with (Bage, Reference Bage1999, p. 29–30). While I feel my own storytelling activity had limited effectiveness, it is something that I feel could be of greater use with practice and developing my skills.

Stories have been an intrinsic part of the human condition for as long as there has been language to tell them and, in many different guises, they continue to be an important part of life in the modern world. As Classicists, we are intimately aware that the myths and legends that we study today are truly ancient tales, kept alive across the millennia not through the relatively late arrival of the written word but thanks to the efforts of generations of oral storytellers. It is only right, then, that we should keep this tradition alive in our own classrooms, disseminating those same ancient stories to brand new ears. Telling ancient myths to modern students, however, is not without its issues. The content of these stories, for example, and the language in which they tend to have been imagined is not always appropriate or accessible to the age group with whom we might wish to share the story (Lister, Reference Lister2005, p.397–8; Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007, p.8). Yet, when done well, lively, engaging storytelling can not only breathe new life into these ancient tales, but also repurpose them as a vehicle for personal reflection, classroom discussion, and group collaboration (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007; Mercer et al., Reference Mercer, Ahmed and Warwick2014). It was with these aims in mind that I chose to tell the story of Vulcan to Year 7 Latin set 5.

This class, the lowest ability set in the year group, comprises 11 students, three of whom have documented difficulties with written work and attention span. One child was absent on the day of the story. I have taught this group for several weeks and found them to be enthusiastic but generally noisy, unfocussed and slow to absorb the new Latin grammar points they meet. The previous week, I had taught the class about Pompeii, based on the material in Stage 3 of the Cambridge Latin Course and we talked about the town's destruction by Mount Vesuvius. The story of Vulcan, therefore, was chosen not only because it is a varied and exciting tale but since it is relevant to the civilisation topics with which they were already familiar.

My story formed part of a 50-minute lesson whose aim was to familiarise the students with the myth of Vulcan and volcanic eruptions and have them recall this themselves. I began the lesson by asking them if they remembered what had happened to Pompeii (which they did) and explaining that, although Romans knew something of the science behind volcanoes, they were also familiar with some myths about why they erupted. This linked the lesson to its predecessor on the town of Pompeii and set up the context in which I would tell the story. Next came the story itself, which I chose to accompany with a PowerPoint presentation comprising large images and key names. This I imagined functioning as scenery for the story I would tell, as well as a resource for the spelling and recall of proper names for later in the lesson. In a deliberate attempt to build suspense and intrigue, I showed the title slide while I was explaining how the class would work: I would tell the story and then I would give the students some props, asking them to work out which part of the story each prop referred to, which order they came in, and finally whether they could use the props to retell the story.

The props I chose were deliberately silly (Figure 1): a strange baby doll (baby Vulcan), mermaid Barbie (Thetis), a toy dolphin, some rocks, plastic bead necklaces, a tiny Playmobil camping chair (Juno's gift), a net and some plastic Duplo fire (volcano).

Figure 1. A selection of the props provided

During the explanation, I tipped the props from their box onto the desk in front of the students and they were instantly interested, trying to guess what on earth the story might be about. The students then asked if we could turn off the lights ‘for atmosphere’, as Walker's students did during her experience with the War with Troy recordings (Walker, Reference Walker2018, p. 38). I had not planned to do this but it transpired to be a nice touch. With the light dim, the PowerPoint, with myself standing in front of it, became the sole focus of attention.

The classroom did not lend itself to much movement but we managed to rearrange the chairs so that all the students, who are normally dotted around the classroom in twos and threes, were sitting together in a shallow arc along the front row. This had the benefit that everyone was immediately in front of ‘the action’, with no other students in their eye line to distract them from the lesson. As I told the story, I was able to walk up and down the line, looking the students in the eye, which made the whole experience more immediate. It also meant that I could observe how involved they were in the story: they paid perfect attention, their faces rapt, more utterly quiet than I had ever seen this spirited class.

My narrative was a fairly simple version of the story of Vulcan from his birth and rejection by Juno, childhood with Thetis, recall to Olympus, marriage to Venus and her subsequent affair with Mars. It ended with her continued infidelity as the catalyst for Vulcan's anger and the consequent eruption of volcanoes. Mindful of keeping the story accessible and appropriate, I deliberately chose a concise narrative, introducing only the main characters and using familiar language or explaining possibly unfamiliar terms, such as sea-nymph or grotto, as part of the story. Since my audience had an average age of eleven and a half, I also glossed over the specifics of what Mars and Venus were doing when they were caught in Vulcan's net, describing them merely as ‘together’.

During my retelling, I tried to make sure that my speech was paced correctly, not too slow as to be unnatural but not too quick as to jeopardise clarity. I varied the speed and tone of my voice slightly at various points and paused at moments I considered to be particularly dramatic and at natural breaks in the narrative. My speech, however, was not entirely fluent throughout the story. I stumbled particularly on names, catching myself before I called Venus Aphrodite but failing to stop myself calling Mars Ares. This was unfortunate and could have seriously jeopardised the students’ understanding of the story. Given their performance in the later activity, however, this proved fortunately unfounded and I may have been saved on this occasion by the labelled PowerPoint slides.

As well as tone of voice and dramatic pauses, I also used a limited selection of gestures and movement to enhance my storytelling: sitting down, for example, during the description of Juno being stuck in Vulcan's chair, and miming her struggle; and bashing my fist against my open palm to add a sound effect to baby Vulcan landing after his fall from the mountain. Since the students started at the latter and watched me attentively during the former, these techniques seem to have proved effective devices, varying the storytelling experience and ensuring the attention of the class.

When the story was over and the lights were turned on, the students continued to sit quietly, not talking or moving as they normally do immediately after an activity has finished. This, beyond anything else, confirmed to me the impact of this episode. I had, however, planned two more formal ways to assess whether the students had understood and remembered the story. First was the prop activity. Having divided the class into two groups, I distributed the props between them, and they set about identifying what each represented and how they combined to form the sequence of the story. They were extremely enthusiastic about this, asking some questions about details (e.g. ‘How many days was Juno stuck?’) but overall recalling the story very well. They embraced the opportunity to work together in groups, debating the significance of the props and negotiating who would play which role in their re-enactments. After ten minutes of discussion and planning, during which I was able to ensure that all students were taking part equally, the groups acted out their versions of the story. Both were surprisingly accurate and detailed renderings, making good use of the props with added dialogue, voices and curious touches, such as pencil-case grottos and a human volcano! As well as being great fun, the activity effectively demonstrated that the students had understood and recalled the story.

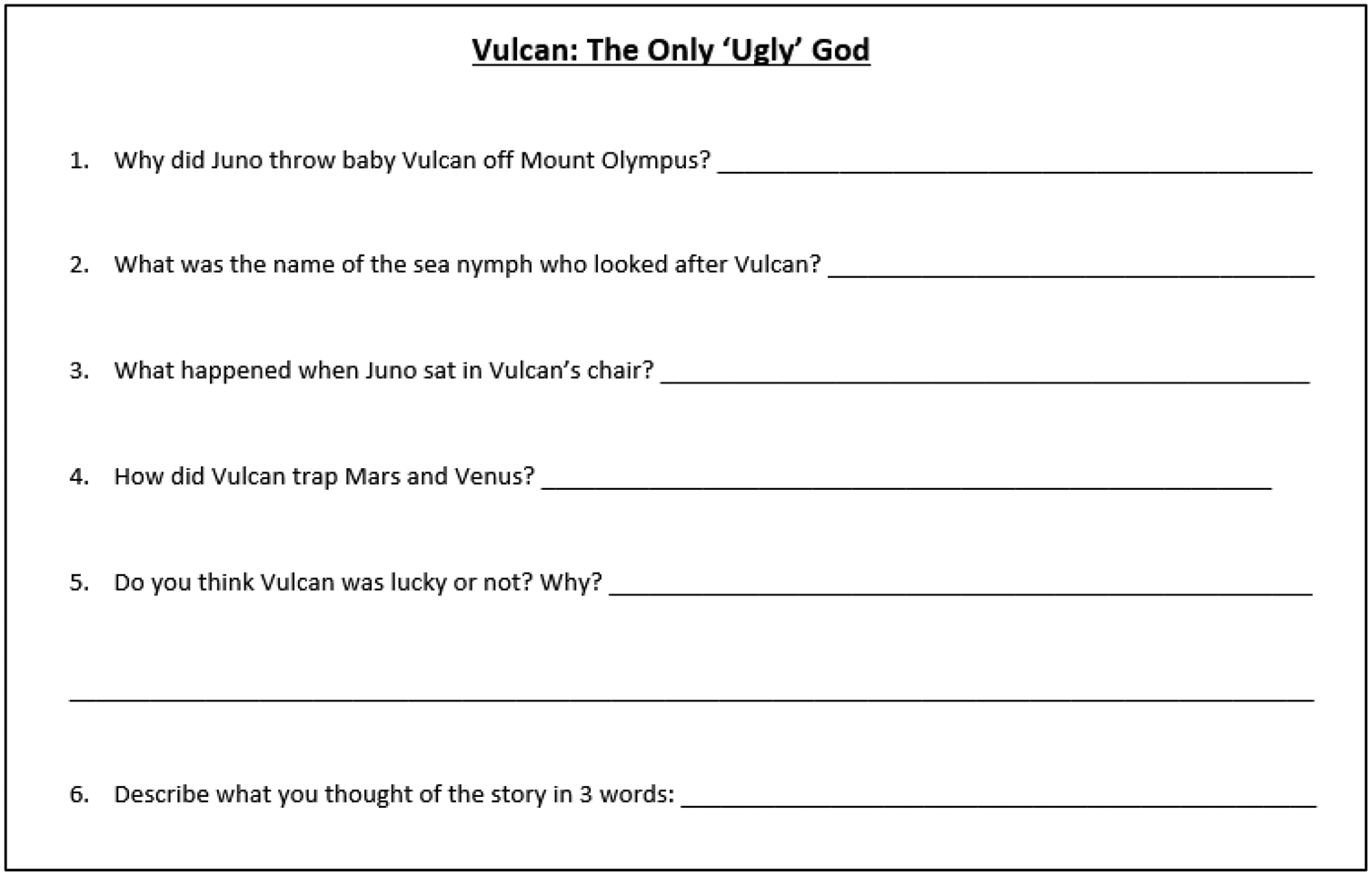

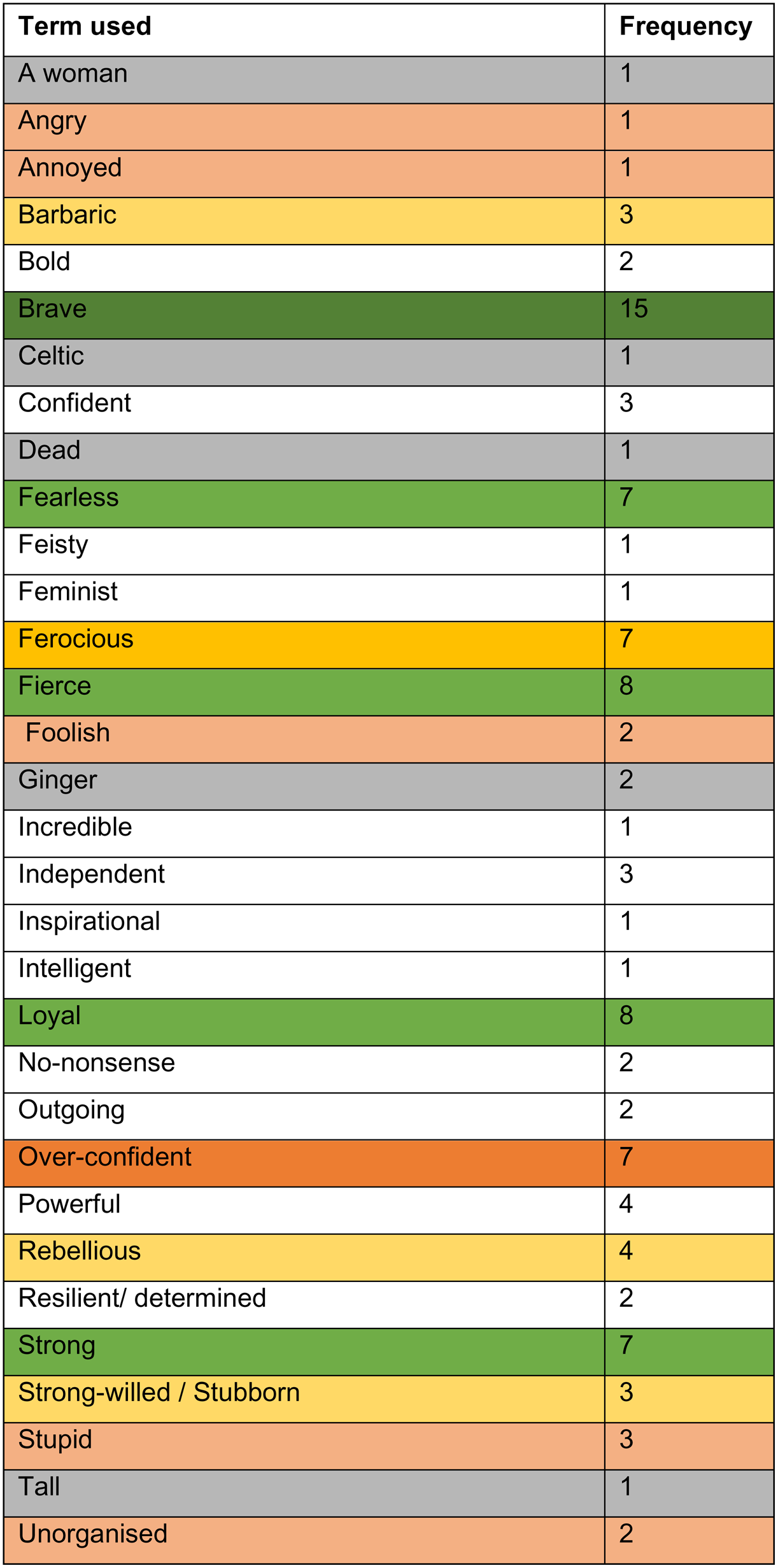

The final activity of the lesson was a short fill-in sheet (Figure 2). This featured a mixture of questions requiring factual recall, analysis and opinion. Originally, I had planned to set a longer version of this sheet as homework since this would not only have given the students more time to reflect and consider their reactions to the story but also assessed their knowledge recall over a longer interval. As the school homework timetable meant that this was not possible, however, the students completed the shorter version at the end of the lesson itself. This they did in record time, keen to show how much they knew. The factual questions were completed accurately across the board, with only the spelling of Thetis (for which the PowerPoint slide was a useful tool) proving a stumbling block. Question 5, which asked them whether or not Vulcan was lucky, produced a wide range of answers, suggesting that each child had thought about the question themselves rather than copied their neighbour. The last question asked the students to describe the story in three words. The 30 words received covered quite a range (Figure 3), with only the single ‘confusing’ giving cause for concern about the clarity and impact of the story. Although ‘interesting’ was unsurprisingly the most popular choice, I was particularly pleased with the variety of words chosen, suggesting, again, that the students had made individual choices about their opinions.

Figure 2. Sample Fill-in Sheet

Figure 3. Student responses to the storytelling

Reedy and Lister (Reference Reedy and Lister2007) praise oral storytelling as a particularly inclusive activity as it allows students to demonstrate their comprehension and analysis without the reliance on the written word (which can prove a significant barrier for some). This almost entirely oral lesson allowed my lower ability set, many of whom have difficulty with writing and reading comprehension, to put aside those struggles for once and fully submerge themselves in the content of the lesson. The responses from the students, both written and oral, indicate its success. They sat captivated during the story itself, enthusiastically embraced the opportunity for discussion and acting, accurately recalled details of the story and provided independent written opinions. The power of storytelling in this case, then, was in creating an inclusive and stimulating environment for the students, transferring the teacher's knowledge and skill and empowering the students to demonstrate their own. It is heartening that the tradition of performative storytelling that was so central to the transmission of culture and collective memory in the ancient world can still prove powerful and relevant in the modern classroom.

For the purpose of this essay, I implemented the telling of Boudicca's revolt with a Year 8 class. I based the script I produced on the information provided in the Roman Britain cultural background section at the end of Stage 14 of the Cambridge Latin Course. I hoped to use the story to add to the pupils’ knowledge of the amalgamation of Roman and British culture in the first century AD. I thought that the story of Boudicca's revolt would give the pupils a more representative picture of Romano-British relationships and a comparison for the roles of women in the ancient world. Up to this point, the pupils had only seen the interactions of Cogidubnus with Roman culture and how he accepts and assimilates it into his life. In contrast, Boudicca refuses to accept Roman superiority and is independent in a way that Rufilla, the highest status woman they have encountered so far, is not.

From the first time I mentioned the name Boudicca, there was audible excitement and a positive reaction from the room. I used my own enthusiasm to encourage theirs and used my tone of voice to emphasise characters’ reactions throughout, particularly to express Boudicca's frustration. I also used gestures to highlight the number of Boudicca's achievements, by counting on my fingers to emphasise that there was a list of Roman cities she had attacked. I had assigned each block of seating an affiliation to a different group or character within the story in order to engage the pupils who did not volunteer for individual roles. To increase their investment in the story, I gestured to each group throughout and asked for their reaction to the events that were unfolding. In retrospect, I would have liked to use the storytelling as an opportunity for the pupils to practise public speaking in the form of reading aloud or as part of a drama exercise. However, I did provide opportunity for some performance in front of their peers. Pupils were asked to volunteer to portray the characters in the story. They would have benefitted from a short script so that they could speak on behalf of their character, but I was prepared to prompt them to encourage appropriate reactions. If the projector had been working, I could have used it to show the pupils visual aids and possibly sound effects. It would be interesting to see how showing the pupils artistic depictions of Boudicca would have impacted their impression of her.

I had intended to use the projector to display a map of Great Britain so that pupils could see Boudicca's movements from city to city in England. Despite the projector not working, I was still able to use a map as a visual aid, by asking the pupils to refer to the map on page 40 in their textbook. This map was useful because it had been produced specifically to aid the cultural background material provided in the Cambridge Latin Course, and so had the area where Boudicca's tribe lived in and the cities that they attacked marked clearly on it. The use of the map helped the pupils to think about the area which Boudicca's army covered and prompted questions about how long it would take for an army to march such great distances. I also increased engagement by asking pupils to volunteer to represent characters and groups. They marched on the spot to show their characters were moving location, changed their facial expressions to display their emotions and dramatically depicted their deaths. The pupils’ acting helped to create a positive atmosphere and to enhance my storytelling. If I were to tell this story again, I would provide pieces of costume or props so that characters and groups would be more easily identifiable. I think that this would also increase the engagement of inactive pupils and give them a greater sense of involvement. Ultimately, the quality of the pupil responses, which I will analyse later in this essay, demonstrates that to some extent my use of tone of voice, gesture and props was effective.

By basing my story on a topic included in the textbook, I was able to ensure that the content would link to both prior and future learning. Before introducing the story, I asked the pupils questions about Cambridge Latin Course characters they had already met (Salvius, Quintus and Cogidubnus) in order to contextualise it. I hope this connection showed the pupils that the story was going to be relevant to what they were studying and that it is worthwhile for them to expand their knowledge about the world in which the stories are set. So that the pupils would also think about the female perspective on Roman Britain, I asked them about the women they had seen so far in the textbook and what their roles were. I used this as a starting point to compare Rufilla and Boudicca as women from different ancient cultures. I then set up the idea that Britons took varying approaches to the arrival of the Romans and that in some cases they actively chose to either be loyal to the Romans or oppose them. The connections to pupils’ previous learning to the beginning of the story, created a positive and welcoming atmosphere. These associations also linked to future learning as in the next Stage 15 about the culture in Roman Britain in the first century AD.

The engagement and inclusion of the entire class was crucial in obtaining the learning objectives for the lesson. All pupils needed to be invested in Boudicca's story in order to characterise her in some way. On the other hand, I had to ensure that I portrayed Boudicca's story in a sympathetic manner so that they could understand her attitude towards the Romans. To encourage pupil engagement, I asked for volunteers to portray the ‘characters’ as they appeared in the story. There were multiple volunteers for each role, and I ensured that anyone who was not chosen initially was given a role next. I also gave the pupils groups to support throughout the story, so that they represented different Celtic tribes and the Romans. I think that this sense of belonging added to the experience and made all the pupils feel involved in some way. Those that were not representing individuals in the story were enjoying watching their peers ‘perform’ and asking questions. I agree with Reedy and Lister (Reference Reedy and Lister2007) that by telling the story in an inclusive way, I ensured that all pupils were engaged to some extent. I used exit tickets for the plenary which meant all the pupils could contribute an opinion about Boudicca without feeling pressured. One pupil that seemed less engaged, surprised me by writing five carefully considered adjectives to describe Boudicca. I felt that all pupils were included but, during the storytelling, I found it difficult to tell how engaged those still seated were. In their study based at primary schools, Reedy and Lister (Reference Reedy and Lister2007) found ‘unanimous’ enjoyment and involvement in the story. I found this kind of unanimous enthusiasm difficult to achieve with the Year 8 class that I was telling this story to. They tend to have a range of engagement levels in lessons and are of a range of abilities. I hope that I was able to eliminate the latter in being a barrier to their inclusion and engagement by making the story accessible to all.

I used the differentiation in my lesson planning to think about how I would assess the effectiveness of my storytelling and pupils’ learning. I decided that the minimum output I would be content with was that pupils would at least have an opinion on Boudicca by the end of the lesson. I hope that most pupils would be able to describe Boudicca using one word and that some would use more than one word. During the lesson, I clarified this by asking for an adjective. I chose to use exit tickets so that pupils did not feel they had to commit their comments to their exercise books. The combination of writing their opinion on a piece of paper and the phrasing of my request to write at least one adjective gave the pupils a sense of freedom, which is displayed in the range of adjectives they used. There were more adjectives used than pupils in the class and I think this shows the creativity that the story and depiction of Boudicca encouraged. After analysing the exit tickets, I found that all pupils had written at least one word as I had hoped, and most pupils had written more than one word. There are 29 pupils in the class, three of them gave single word responses and the rest wrote down more than one word. In addition to this, approximately a third of the pupils wrote down five words or more. There were a few terms used that did not comment on her character or which were ambiguous, in that I cannot be sure if the pupils thought that they were admirable qualities or not. I have given these in Figure 4 and colour coded them to show whether I considered them to be positive or otherwise and differentiated within these categories to show the frequency with which they were given by the pupils.

Figure 4.

If I were to teach this lesson again, I would aim to use storytelling to improve pupils’ creative writing and Latin prose composition. This could be achieved by asking the pupils to produce a piece of writing about the Battle of Watling Street or by asking the pupils to write about a short description of Boudicca in Latin. This would then link the adjectives they provided to describe Boudicca at the end of the lesson and what they have been learning about adjectives. Though the evidence that Skjæveland (Reference Skjæveland2017) uses in support of the benefit of students retelling stories comes from primary schools, I would still be interested to find out to what extent the pupils retelling the story would help them to remember it. It would certainly engage most pupils and show which parts of the story had been portrayed most effectively in my telling of it. This would also give the pupils chance to make their own decisions about how to present the story as Skjæveland (Reference Skjæveland2017) believes is beneficial to their learning.

Story Transcript

Teacher: As well as learning Latin, your textbooks give us the chance to learn about the society in which the stories are set. Today's story is set in AD 61, before Salvius arrives in Britain. Can anyone remember the name of the British King that Salvius and Quintus are going to visit?

Student: Cogidubnus.

Teacher: We have heard about Cogidubnus already and we will see him again in Stage 15. Cogidubnus had a good relationship with the Romans that had moved to Britain. He had accepted that they were more powerful than him and so was allowed to keep his position as king. However, he had to collect taxes on behalf of the Roman governor, who was in charge of most of Britain at this time. But today I am going to tell you the story of someone who refused to let the Romans control them… Boudicca.

Now all I need you to have out is the map on page 40 in your textbook.

Boudicca was Queen of the Iceni, a tribe that lived in what we call East Anglia. You can see the name of her tribe, the Iceni, on the map. Boudicca was rich and powerful in her own right. She could own her own property and divorce her husband.

Can you think of another woman you've met in the stories so far?

Student: Salvius’ wife, Rufilla

Teacher: Rufilla had an important role in the household but couldn't really make all of her own decisions. However, Boudicca ruled the Iceni with her husband, King Prasutagus.

1. Everything changed when Boudicca's husband, Prasutagus, died.

2. The Romans started to demand the Iceni's land for taxes.

3. Boudicca refused to hand over her lands to the Romans and so they captured her and her daughters and tied them to a post and beat them. The Romans had hoped this would make Boudicca give in and hand over her lands.

4. However, Boudicca did not give in. She and her people were outraged and decided to fight back.

[3 volunteers to represent Boudicca and her daughters from the left-hand side of the room come to the front of the classroom. Pupils are told those remaining now represent the rest of Boudicca's family and tribe]

5. Boudicca gathered an army and marched them to attack the Roman city at Colchester. [Camulodunum pointed out on map in textbook]

6. Boudicca and her army took control of Colchester easily. They took all the valuables from the city, destroyed most of the buildings and killed many Romans.

7. When other tribes found out about Boudicca's success, they joined her army.

[The central block of the room will represent the other tribes. 3 pupils volunteered so I allowed them all to come up to the front]

8. With such a huge group of fighters, Boudicca decided to attack Saint Albans (Verulamium) and London (Londinium). The Romans tried attacking them on their way but didn't affect them at all.

[Cities pointed out on map]

9. Boudicca and her army destroyed Saint Albans (Verulamium) and London (Londinium). Again, ruining the cities and killing Romans.

10. Their next task was to defeat the Roman Governor, Suetonius, and his army.

11. Battle of Watling Street

Boudicca marched North. Suetonius marched south. Boudicca's army was much bigger than Suetonius’. Boudicca encouraged the families of her warriors to come and watch the battle, so that they could watch them defeat the Romans once and for all. But the Romans’ tactics were better than Boudicca's. They were well trained and organised. When Boudicca tried to leave the battlefield, she and her tribe were blocked by their supporters. The Romans killed Boudicca's army and then her supporters. It is said that Boudicca did not want to be humiliated and so couldn't let herself be killed by the Romans. Instead she and her daughters chose to take poison.

12. Romans then took control of East Anglia.

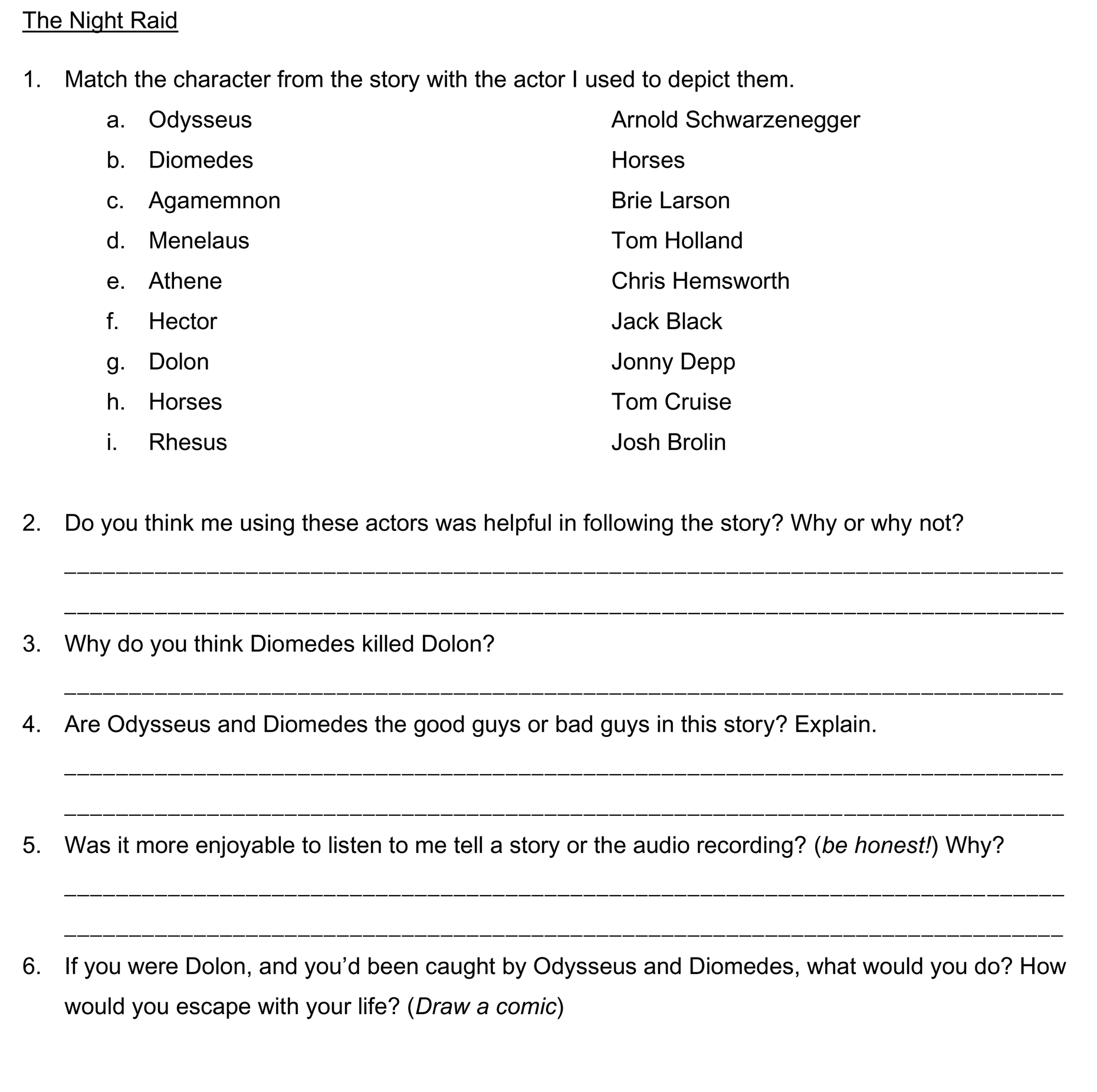

I presented to my Year 8 Classical Civilisation class the story of ‘The Night Raid’, based on Book X of the Iliad, in an attempt to improve oracy (both my students’ and mine), compare the effectiveness of the War with Troy audio recordings with a live performance, and supplement our ongoing module on the Trojan War. While I was able to successfully engage the students and teach them an interesting and memorable lesson, I do not believe I met my first goal as successfully as I could have due to my method of assessment, which was to fill out a worksheet. I also learned that my students were not as fond as the War with Troy audio recordings, which we had listened to in several prior lessons, as I had previously assumed, at least in comparison to my own performance, due to the latter's humour and interactivity, a discovery which has already altered my future lesson plans. These qualities certainly did lead to a successful lesson, however.

To aid in my telling of ‘The Night Raid’, which took approximately 13 minutes, I used rudimentary puppets, with famous actors and actresses representing each character (See Figure 5). These ‘roles’ had been assigned at the end of the previous class, in which I gave the students a brief description of each character and asked them who they would cast.

Figure 5. Puppets for retelling the Night Raid

This lesson was in fact the fifth in our module on the Trojan War, meaning the students had already encountered most of these characters and understood the context of the scene. This eliminated a common difficulty with narrating stories from the Trojan War (as experienced by Morden and Lupton while making War with Troy, for instance (Lister, Reference Lister2005)). Although it was apparent that the students were often simply naming whoever came into their heads first (as evidenced by the amount of hands raised before I had read off a character's name or description), most of their selections were at least plausible, if not surprisingly fitting (e.g. Arnold Schwarzenegger as Agamemnon). This ‘casting call’ also had the benefit of building students’ anticipation for their next lesson. When students walked into class on the day of the lesson and saw the puppets lying face-down on a table, some immediately deduced what they were, and excitement filled the room.

One unexpected effect from using these puppets, however, was the large amount of noise that occurred every time I uncovered one, e.g. at the reveal of Arnold Schwarzenegger as Agamemnon or Brie Larson as Athene. This was always light-hearted and involved though, as evidenced by the students’ laughter and remarks such as ‘Hey, Arnold!’ during the former, or ‘Oh, it's Captain Marvel’ during the latter. These puppets also at times increased student engagement, as when one wondered aloud who was playing Odysseus (amusingly, I believe this was said by the student who had cast him as Jonny Depp the previous week), and they undoubtedly injected humour into my performance. Having taught this group several times over the previous weeks, I knew I might struggle to hold their attention with a completely serious story (which Book X of the Iliad certainly is), especially since the class was after lunch and thus more energetic. I accordingly attempted to create a lighter environment by allowing the students to occasionally speak and having fun with the puppets, being sure to shake them up and down when they talked. These efforts were noticed and appreciated by the students, as heard in the resounding laughter the first time two puppets spoke, and in the students’ assessments of the lesson (see below). To further increase student engagement, I was also sure to change the speed of my voice at certain times to match the events of the story and emphasise dramatic moments, often eliciting reactions from students.

While student engagement and enjoyment are obviously of great importance, it is also necessary to ensure that the performance is actually educational. I therefore ended the class by having them fill out a worksheet, making them think critically about the story in a way that allowed me to evaluate how much they retained and what they had thought of the lesson (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

It is here I believe I missed an opportunity to further strengthen my students’ oracy. I am following Mercer et al. (Reference Mercer, Ahmed and Warwick2014) here in their definition of oracy as ‘skills in using spoken language… [which all children] need for educational progress, for work and for full participation in democracy’. The method of developing this skill is bipartite, however; it requires both oral and aural training (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007). While my performance was certainly beneficial to my students’ aural capabilities, my worksheet unfortunately provided little aid to their oral ones. There was still strong evidence of student retention and learning, however, in their ability to connect the story to previous lessons and create one continuous narrative. The majority of students seemed to understand my joke about Patroclus’ death, covered last lesson, and one student was even able to trace a reference to Achilles’ horses back through several lessons, recalling first that the Greeks had possession of them and then that they had been a wedding gift of Poseidon's to Peleus and Thetis, something mentioned almost casually in our first lesson on the Trojan War two weeks prior. There is indeed some evidence that these oral performances can aid in students building a larger narrative in their heads (Lister, Reference Lister2005), as is clearly shown here.

Turning now to the worksheet, many students experienced some difficulty filling out Question 1, being unsure of the names of actors and subsequently requiring help from me or other students. Despite this, they almost unanimously answered for Question 2 that they considered my use of the actors to in fact be helpful in following the story, with only one student possibly stating it was not (their response is incomprehensible, although it seems to be in the negative). Most students reported that having actors they knew represent the characters helped them understand what those characters’ personalities were like and to visualise the story, something they had previously struggled with. Students generally were able to infer from the story the answer to Question 3, although many did not, but most answered to Question 4 that Diomedes and Odysseus were the good guys of the story, despite their murdering of sleeping soldiers. It is reasonable to infer this is because I portrayed them as the protagonists, with one student saying as much: ‘[They are] a good guy in this story because it is from there points of view [sic].’

Ignoring the unavoidable confounding variable inherent in me asking this question, the students were unanimous in stating for Question 5 that they enjoyed watching me perform more than listening to the War with Troy audio recordings. More significant than this preference, as big an ego boost for me as it might be, are the reasons why they prefer me. The most common answer was that it was easy to interact with me and ask me a question during the story, something intrinsically impossible with the audio recordings. Another frequent response was that I have ‘on point story telling skills’ or simply that my story was funny, with one student even clarifying: ‘I think audio recordings are dull and boring’. The visual components of my performance were also appreciated by some. Two students specifically stated that my body language was useful to them, an interesting statement for two reasons: 1) because both were ESOL students and thus often require more clues to follow a story, and 2) because they were sat alongside one another while filling the worksheet out, perhaps indicating some ‘teamwork’ in writing this answer.

My puppets and movements also seem to have greatly benefitted several students in a significant way, and their answers to Question 5 are reproduced (with slight editing for comprehensibility) below:

Student 1: You telling the story, because we could all see the same thing instead of having different ideas of it.

Student 2: It helps me lots seeing it, as sometimes words go blank but pictures help as I have a good memory.

Student 3: Because we could see it as a representation of them instead of a painting [this might refer not to the audio recordings but instead my PowerPoints, in which I would deliver a narrative with simply pictures of the scene alongside factual bullet points or short bits of dialogue].

Student 4: I think it was more enjoyable to listen to you telling a story because you can see what happens.

In these responses, as well as those of the ESOL students above, we can see an argument against a purported benefit of listening to only a narrative without visual aids, namely that it ‘has been very successful in triggering children's imagination – in the literal sense of creating images in their minds’ (Lister, Reference Lister2005, p.407). It is perhaps relevant here that this class is a bottom set, and many of the students have some sort of learning disability, which could make creating such images more difficult.

In conclusion, my performance of ‘The Night Raid’ and the subsequent worksheet was beneficial to my students in many ways, including interactivity, engagement, critical thinking, and building a larger narrative. It was not as successful as I had initially hoped in developing their oracy, however, which would have required a more oral method of feedback from the students, for instance a large class discussion, organised debate, or retelling of the story by the students themselves Significantly, some of these benefits are absent from listening to the War with Troy audio recordings, which is something for me to keep in mind when teaching these students or those like them in the future.

I decided to tell a mythological story to my Year 10 Latin class of 28 students. This has been my main class and I thought the students would benefit from a different style lesson in order to broaden their experience of the ancient world. It was also an opportunity to try and engage those students who rarely contribute in regular Latin lessons. The initial plan was to share the story of Heracles, a central myth that I felt was important for any Classics’ student to know. However, after discussion with my mentor and a few Sixth Form students in my other classes, I felt that most of the Year 10 students would have a good knowledge of the myth already. Therefore, I finally settled on the myth of Jason and the golden fleece. This myth has a number of exciting episodes and introduces the colourful character of Medea which I thought would provide opportunities for discussion within the lesson. My principal lesson objectives were for students to gain an understanding of Jason and the golden fleece, and to engage with the characters of Jason and Medea. I largely used students’ responses during the lesson and reading through the written work in their exercise books to evaluate the effectiveness of my storytelling and their learning.

My retelling of Jason and the golden fleece arose from researching the myth and selecting the key moments that were not only exciting, but ensured the story as a whole flowed well. To help prompt good listening from my students - something that has been challenging in previous lessons - I warned them at the beginning that there would be a quiz later in the lesson on the material covered. In order to make my retelling engaging, I tried to vary my tone of voice and evoke responses through this means. For instance, when recalling how Jason was set the task of sowing dragons’ teeth in a field, I emphasised the ‘minor’ detail that Aeetes leaves out from his instructions: that the teeth will grow up into fully-grown armed men! This elicited some laughs and smiles from the students. I also tried to include instances of direct speech in order to make the characters seem more real and immediate. Aeetes had a number of lines attributed to him and I was able to use my tone of voice to communicate the character's thoughts: for example, when Aeetes responds to Jason's initial request for the fleece, I demonstrated his obvious disingenuity. Using the present tense was also a choice I made to try and encourage students to imagine themselves in the story, hearing it unfold before them. Furthermore, I frequently asked direct questions to the class throughout. Some were to give students the opportunity to share any previous knowledge, for example giving the name of Jason's ship; more often I was questioning in order to help engage them with the characters, and use their understanding so far to predict what they thought would happen next. This was particularly seen when asking about Medea's situation once Jason had the fleece: ‘What's the problem now for Medea?’ I felt it was important for students to spend a moment realising that Medea's actions went against her father and so the escape that follows was the inevitable consequence.

I decided not to use any physical props as I felt that it would distract rather than enhance my storytelling for this group. I tried to use gestures to liven up the story and provide a sense of movement. For example, I pretended to throw a stone when relating Jason's actions against the armed warriors; I also gestured with my arms when describing how the dragon was ‘so large that its body could fit around an entire ship’. These seemed to be effective as students were following where I was pointing. I could have made a greater use of movement around the classroom as I largely stayed stationary. Although there were no physical props, I did decide to project images on the screen behind me for the students to look at whilst I told the story. I thought this would be effective as another means of encouraging learning, especially for the more visual learners, and also helpful for a summary quiz at the end. These images were carefully selected to correspond with each key moment in the myth. I also included a small family tree as I felt my explanation of Jason's family would be much clearer if I could point to the characters on the screen. After I had finished, I showed the images again on the screen, this time with a small Latin phrase or word which I could refer to in my revision questions. For example, on slide 12, I asked students to identify who was being shown and they were quick to respond with ‘the daughter of Aeetes’ i.e. Medea. I also tried to include Latin words that formed part of the next few written activities to increase familiarity. I felt that the images strengthened my storytelling by providing a visual focus, and also had the benefit of providing prompts for myself.

My chief learning objective was for all students to know the basic outline of the story of Jason and the golden fleece. Reedy and Lister have written that oral storytelling promotes ‘high levels of engagement and inclusion, leading to enhanced understanding by the pupils’ (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007). This engagement was present, encouraged through the use of gesture, images etc. that form part of an oral retelling. It was especially evident that this different style attracted students. Inclusion was also an area that I was keen to work on. To this end I carefully selected the vocabulary used in my storytelling in order to promote accessibility and ensure all students could understand the story. The different lesson style also seemed to have this effect: students who usually have to be specifically asked were volunteering responses to questions throughout the story and during the following discussions. Through the class’ responses, I am confident that this learning objective for all was achieved.

When planning the lesson, I also aimed that most students would be able to form, and defend, their opinion of both Jason and Medea. In order to prompt and develop this, I planned a few written activities to follow my storytelling in the lesson. First, students were each given an image of Jason and Medea and asked to label them using the Latin adjectives given on the board. To complete this task, students had to look up any unfamiliar vocabulary - textbooks were provided - and evaluate which adjectives seemed appropriate for which character. This promoted useful discussion and. reviewing exercise books following the lesson, all students were able to carry out this task. Some students had time to supply reasons for their choices but most were able to do this orally when asked as we went through the adjectives. Students were clearly engaging with the characters with some arguing that fortis (brave) could be applied to both Jason and Medea, and others concluding that Jason was felix (lucky) to have had Medea's help.

A final activity was for students to discuss in pairs, ‘Should Medea be blamed for her actions?’. This explicitly followed the lesson objective that most students should be able to defend their opinion of Medea. In fact, all students were able to write a sentence with their view. Most thought that Medea largely should not be blamed because she was made to fall in love; however the general conclusion was that it was her choice to slow down her father by violently killing her brother. It was encouraging to hear students defend their views during the feedback discussion for this activity, and also to see students responding to each other in an informal debate. This is evidence that such an activity can be used effectively to develop students’ communication skills, the importance and desirability of which by future employers has been emphasised by Mercer et al. (Reference Mercer, Ahmed and Warwick2014). Such skills are currently neglected in the school curriculum.

My main assessment methods for monitoring the quality of my teaching and students’ learning were oral responses from students arising from the lesson and a few written activities. I felt that solely assessing students’ learning from written work would unfairly disadvantage those who struggle with literacy. My starter consisted of students studying a painting of the golden fleece myth and spending a few minutes discussing what they could identify in pairs before feeding back as a class: no written work was required. This was an effective gauge of who in the class had any previous knowledge of the myth: this only applied to a couple of students. My summary quiz was also all verbal and I was careful to include feedback discussions after each written activity to reinforce learning. Lister argues for the effectiveness of follow-up discussions to allow teachers to gauge how well ‘students have grasped the thread of the narrative’ (Lister, Reference Lister2005, p. 404). As well as a recap activity, I wanted to test students’ understanding of the characters by challenging them to use what they had heard to make judgements about both Jason and Medea. This was effective as students had to use knowledge recalled from earlier in the lesson to make and justify their decisions. There was a variety of responses from the class which suggested that students were engaging with the myth and forming their own opinions. For instance, some students argued that the adjective non fidelis’(not faithful) only partially applied to Medea since she was loyal to Jason but not to her father. The class was warned here that Medea's story continued with a number of violent twists: slide 21 was shown as a quick taster of what they could research in their own time. To take my assessment further, I could have selected a few students and carried out a quick survey after the lesson, asking for in-depth feedback on how effective they felt my storytelling was. In order to assess whether this learning had formed part of their long-term memory, I could have quickly gathered what students knew in the following lesson to reinforce the knowledge gained.

In conclusion, my telling of a mythological story was effective in engaging the Year 10 students, both as I told the story and in the following written activities and discussion. Any initial concerns that this age group of students would not respond well in a storytelling lesson were soon allayed. The use of gestures and direct questions prompted students to imagine themselves in the world of the myth, analysing the emotions of different characters and predicting what was about to happen. Asking students to recap the story in a quick summary quiz helped assess their learning so far in the lesson. This was taken further as students were asked to analyse the characters of Jason and Medea. Assessing through pair discussion and class feedback alongside written work enabled students whose literacy is weaker to demonstrate their understanding and contribute to the lesson. It also provided an opportunity to develop students’ oral skills, especially when promoting a debate on the character of Medea and the judgement of her actions. I could have undertaken a more in-depth study but these methods enabled me to assess the quality of learning for the whole class, both during the lesson itself and afterwards looking through exercise books. A number of students asked questions about the future of Jason and Medea which is evidence of real interest in the story. I believe lessons with this focus on oracy should be used more frequently in the curriculum.

Transcript

Teacher: Today we're going to have a slightly different lesson. You've been looking at myths about the Trojan War and its causes - with Paris and the golden apple etc. Today we're going to look at a Greek myth that takes place before the Trojan War. Now I'm going to give you 2 minutes to look at this picture [See slide 1]. Talk about what you can see with your partner - can you identify any of the characters?

[Students discuss - some recognise golden fleece]

Teacher: OK, Year 10, what did you talk about with your partners? What can you see here?

[Students identify dragon, golden fleece, man with a club, identified with teacher's help as Hercules]

Teacher: So, if we have the golden fleece here, who is this person? Does anyone know?

Student N: Jason.

Teacher: Excellent! So, we're looking at the story of Jason and the golden fleece. Now I'm going to tell you this myth - while I'm talking you need to be listening carefully, looking at the pictures on the screen behind me and thinking about what they're showing. There'll be a quiz at the end so pay attention to the details.

[Slide 2] Ok, so our story starts with Jason - he is the son of Aeson. Before Jason was born, his uncle Pelias took the throne instead of Aeson. So, Jason's father should be ruling but instead it's Pelias. But Pelias has received an oracle warning him that one day a descendant of Aeson will come and take revenge. Pelias believes that this is Jason. So, what do you think Pelias wants to do with Jason?

[Students call out answers - ‘kill him’, ‘get rid of him’]

Teacher: Exactly. Pelias wants to kill Jason! But he can't just do it himself - it wouldn't look good, it might cause unrest, so what he does is Pelias sends him on a mission.

[Slide 3] Pelias sends Jason on a mission that he believes in impossible. He thinks Jason will be killed, that he'll never see him again - his problem is solved. Jason's mission is to steal the golden fleece. This was from a golden ram of Zeus so incredibly valuable. You might wonder, ‘Why is this impossible?’. Well, firstly the fleece is owned by King Aeetes of Colchis so Jason can't just come and take it. And also, it's guarded by a dragon that is said to be so large that its body could fit around an entire ship. It also never sleeps so you know, not very easy for Jason to slip by and take the fleece. So first, owned by King Aeetes; second reason, guarded by a dragon. Pelias feels pretty confident. [Slide 4] So what does Jason do? He recruits 50 of the best heroes from Greece - people like Heracles that we saw in the picture earlier, Orpheus also who you might know. They sail with him in a ship. Does anyone know the name of this ship?

Student B: The Argo.

Teacher: Excellent. So this voyage is the Argonautica which you might have heard of. Now most Greek heroes have the support of a god or goddess to help them with their missions. Jason is no different - he is helped by the goddess Hera. Can anyone tell me who Hera is?

Student N: Zeus’ wife.

Teacher: Brilliant. Yes, she's the wife of Zeus. So, she enlists the help of another goddess, Athena, to help create this ship. So, they sail to Colchis, they have an adventurous journey, lots of things happen and eventually they arrive in Colchis. Now Jason doesn't just sneak in, try to take the fleece and leave - he goes straight to King Aeetes and asks for the fleece. How do you think King Aeetes responds to this? Someone has just come and asked to take away the fleece - do you think he says, ‘Yes of course you may take the fleece that's so valuable that I have a dragon to protect it?’

[Students call out ‘No!’]

Teacher: Of course not! Aeetes has no intention of giving it to Jason. But he says to him, ‘You can have the fleece, but you have to complete these challenges.’ Aeetes sets him challenges that he's sure Jason will fail. Can you see a theme here? Pelias sets Jason a challenge that he's sure Jason will fail; Aeetes also sets him a challenge he thinks he'll fail. But we can see why Aeetes was confident.

[Slide 5] Does anyone know who this woman is?

[Students look unsure - one guesses Hera]

Teacher: Not Hera, but good guess. This is Medea - she's the daughter of King Aeetes. She's got divine origins; she's clever; she's crafty; she has magical powers. She is not a normal Greek woman! Now the goddess Hera is worried about Jason and the tasks he's been set so she asks the goddess Aphrodite to make Medea fall in love with Jason. Do you think this would help?

Student T: Well, Aphrodite's the goddess of love.

Teacher: Yes, she is the goddess of love and by making Medea fall in love with Jason, this ensures that Medea now uses all her powers to help him. He's got a powerful ally on his side.

[Student calls out: But you won't necessarily help someone because you love them. Other students react to this - whole class having conversations countering this thought]

Teacher: [Slide 6] So this brings us on to Jason's challenges. First Jason must plough a field using two fire-breathing bulls. Not normal bulls - fire-breathing bulls! Jason clearly cannot do this on his own. But he has Medea on his side now: she gives him an ointment that protects him from fire for a day. So, Jason is able to complete this task.

[Slide 7] For his second task, Aeetes tells Jason to the sow the teeth of a dragon into the field. But Aeetes leaves out a ‘minor’ detail. What Aeetes doesn't tell him is that once Jason's sown these teeth into the ground, they'll sprout up into fully-grown armed men - an army - and kill Jason. Or so Aeetes hopes. So only a minor detail that Aeetes leaves out here. Fortunately for Jason, Medea knows this. Medea tells Jason that these armed men will sprout up and she also tells him how to defeat them. She tells Jason that if he throws a stone in the middle of the soldiers, they'll be confused, they won't know who threw it, where to look - that they'll turn on each other and kill each other. So this is what Jason does: he throws a stone, the soldiers are confused, they turn on each other and kill each other. So how do you think King Aeetes is feeling at this point?

Student J: A bit annoyed really.

Teacher: Yes, annoyed. A bit worried, anxious - he didn't think Jason would be able to complete these tasks and now there's still this threat to his golden fleece. Remember that he doesn't know that his daughter Medea has been helping Jason. So, Aeetes says, ‘Ok, fine. You can have the fleece. But you have to kill the dragon that guards it.’ Remember this is the dragon that doesn't sleep and is so large that its body fits round a ship. So how is Jason going to do this? Who steps in to help him?

[Slow to respond]

Teacher: Who has helped him plough with the bulls and defeat the soldiers?

[A few students call out ‘Medea’]

Teacher: Exactly. Medea steps in, she gives Jason some magic herbs to make the dragon fall asleep. So, Jason uses these, the dragon falls asleep and Jason is able to sneak past and grab the fleece from the tree where it's hanging. He's now got the fleece! What's the problem now for Medea? What's her situation? What has she done?

Student D: Well, she's gone against her father. She's betrayed him.

Teacher: Excellent, ——. She betrayed her father: she's helped Jason to get through all these challenges, and to take the fleece that belongs to her father. So, she now has to escape Colchis. Jason needs to escape because he's taken the fleece which Aeetes did not want to give up; Medea needs to escape because she's betrayed her father.

[Slide 9] So they have to flee. But as they flee, they're pursued by Aeetes. Medea begins to show her true colours here - she does something pretty awful. She kills her brother [students murmur] and then cuts up his body - it's really not nice is it - and throws the pieces in the sea. She does this to distract her father, to slow him down. Can you think why this would be an effective way to slow her father down?

Student T: Well he would need to collect the pieces to bury him, wouldn't he?

Teacher: Exactly! Aeetes has to stop and collect all the pieces in order to give his son a proper burial which was really important to the Greeks. So, this is where we leave our story. Jason and Medea go back with the golden fleece to his home, where Pelias was still ruling. Pelias doesn't want to give up the throne so Medea plots to kill him so Jason can become king.

I chose to retell the myth of Medea because of the contentious nature of her actions and the visceral reactions that arise in people because of that. I am fascinated by the idea that, despite this ‘sacrilegious crime’ (Johnston, Reference Johnston2008) that she commits, directors, translators, and even, arguably, Euripides himself ask us still to see her somewhat sympathetically. I wanted to focus on the creation of that sympathy for the character of Medea and how - and if - that should be done. I also wanted to focus on the idea of ‘retelling’ a story and how each incarnation of a myth has a different agenda, a different bias, and a slightly different story to tell. Finally, I wanted to look at the way in which these fantastic stories that we have from the Greek world are introduced to pupils and to try to consider whether or not there is a better alternative to what we do at the moment. Due to the awful nature of Medea's actions and the theoretical nature of the topics covered, I chose to do this session with Year 13. I also chose this year group because of a sense of trust which I believe has been built up between the pupils and myself before the session, and because there is a high chance, if they do not choose to study Classics beyond this year, that they will never learn about the myth of Medea which I believe would be a huge loss for them. I was extremely excited to do this project and have decided that oracy and storytelling are tools which I would be very keen on including more in my lessons in the future.

The intent of my session was not to explore with the class whether or not Medea is deserving of pity and sympathy. In fact, that is an angle which I am conscious that I will have to be careful to avoid given the limited time frame (a single, 35-minute lesson). Instead, the focus is intended more to be introducing the pupils to a version of Medea that they should have little problem feeling sympathy for before revealing her crimes as opposed to the other way around which is how it is so often done in teaching. I have tried to do this by providing heavily cut versions of a script (as neutral a script as possible which I accessed online) that shows Medea as powerless as possible with the only other speaker being Jason who is shown in as sexist a light as I could manage while still being accurate to the story. My original plan was to have pupils read the parts of Medea and Jason, but, after I ran through the lesson with some fellow postgrads I found that this meant that, firstly, the reading was likely to be more stilted and therefore less accessible to other members of the class, and, secondly, that it resulted in some students relying on the written script. This undermined the purpose of the session and so, instead, I decided to read the part of Medea and asked the class teacher to read Jason's lines. I also decided to have selected quotes (indicated in bold on the script) displayed on the board that pupils would be able to refer to if they were really struggling with a question, but I tried to keep these to an absolute minimum. I was also careful to give pupils enough context to the myth to be able to understand the passages, but to keep it vague enough (mainly through eliminating names of people and places) that pupils who may have heard of the myth, but not directly heard it told would not have their memory jogged. Furthermore, I encouraged them at the beginning of the lesson to rely on my version of the story rather than any prior knowledge they may have and to ‘play along’ for the whole session. This was why I needed the element of trust in the pupils because the lesson hugely relied on them trusting me to fill in the gaps and me trusting them not to spoil (in the sense of give ‘spoilers’ to the plot) for the rest of the class.

One of the reasons why I was so keen to focus on avoiding ‘spoilers’ for Medea killing her children even though this act is not presented as a plot-twist in the play is because I think the way in which we introduce our pupils to these stories needs reconsidering. When my A Level texts were given out, Medea was described to me as ‘the play where she kills her babies’. Although, at the time, this blasé way in which the plot was summarised did not bother me, I think that it is an example of the way that emotive, brilliant, and complex texts can be treated so poorly simply because they are being read by schoolchildren. In school is one of the few times that a story would be treated in this way: we would be horrified if the cashier at the local book shop spoiled the end of our new book just as we were buying it. An argument can be made that, for the purpose of reading these texts fully and critically, pupils need to know what is coming to pick up on foreshadowing. There is also an argument that the Ancient Greeks would go to see these plays knowing the myths beforehand, but I think that there is a lot to be said about the first time someone hears a story. Although after that they may have to go on and analyse it in minute detail, I believe that this trivialising and undermining of stories may be what causes pupils to so often not enjoy the texts that they study in school. If we treat them - even if only for a single lesson - as a text which can be surprising, engaging, and shocking rather than just informing, we might find that pupils end up actually enjoying the texts that they are reading.

Finally, something I wanted to focus on was the idea of retelling and re-performing a story. Again, this is one of the reasons that I chose a play as my myth because it is easy for the pupils to grasp the ‘re-performance’ aspect of that form of text. I was keen to highlight the idea that each writer of the myth, each translator, each director (or a whole production team) would have a different focus and agenda that they were trying to draw out with the story. Even then, I wanted to go deeper and encourage the pupils to think that each person in the theatre on the same night, watching the same performance, might have a different take on that performance depending on their own personal schema. Finally, there is the idea that each of those members of the audience is then going to pass on a slightly different version of the story afterwards and thus the chain continues. I was inspired in this by the quote by Lupton that ‘When you're telling a story, the person you heard it from is standing behind you as you're speaking etc.’ (Bage, cited in Lister, Reference Lister2005, p. 403) I wanted the pupils to be aware that, even though the retellings of the myths they already know may well be have a much more subtle way of transmitting this agenda than the method I used, that does not mean it does not exist, but it also does not mean that it is conscious. I will encourage them to consider that, for example, a man may well have a different attitude to the play to a woman and that a woman with children will likely have a different attitude to a woman without children or who has lost children and so on. This is partly to encourage them to be critical not only of the texts that they are studying in class - not only in Classical Civilisation, but in English, History, and other subjects, but also to encourage them to seek out retellings of other plays and myths even if they already know them. I have used this opportunity to potentially introduce them to a new myth that they may not have had exposure to if they do not continue with Classics, but I am hopefully also using the experience to inspire them to seek out other retellings - either of new stories or of ones with which they are already familiar.

Reflection

I was very pleased with the way in which the class interacted with the story and with the ideas I presented to them through this activity. I was satisfied that, although I think some members of the class did work out which story was being told, they all interacted with the story that was being presented to them rather than relying on their own knowledge. I think especially the accessibility of the text made the activity especially interesting with this class as I have noticed that, with written texts, there tend to be one or two pupils who seem to be quicker at absorbing and processing written information and therefore can slightly dominate the conversation. I was happy to hear in the discussion that most of the pupils took time to speak. I do not know if this is to do with the reduced pressure on them in this class (I told them previously it was me being assessed not them and so they may have been keen to speak up to come to my aid) or to do with the fact that they did not have to read or take notes, only listen.