Introduction

Calls are increasingly being voiced by educators and teachers of classical languages for a more communicative, and humanistic, approach to the teaching of classical languages – see e.g., Hunt (Reference Hunt, Lloyd and Hunt2021), Lloyd (Reference Lloyd, Lloyd and Hunt2021), Manning (Reference Manning, Lloyd and Hunt2021). Against this background of proposed changes in pedagogy, this paper proposes parallel changes in assessment, because assessment impacts pedagogy (see Rind et al, Reference Rind and Mari2019, Cheng, Reference Cheng2005), arguing the case for a communicative test of reading and language use for learners of Classical Greek. Discussion first explores the extent to which Classical Greek currently features in European schools and the traditional – i.e., analytical rather than communicative – pedagogies by which it is predominantly taught.

For a number of reasons, such as teacher interest in communicative approaches to language learning, learner interest and motivation, as well as efforts to improve uptake by schools, a considerable number of academics and practitioners have been advocating that Classical Greek be taught in a similar manner to modern languages: that is, based more around communicative approaches to language teaching – see e.g., Richards & Rodgers (Reference Richards and Rodgers2014). Following an exploration of a communicative approach in teaching, the current paper then moves to an examination of assessment in classical languages, where there would appear to be even less use of modern methods and where traditional, grammar-translation approaches to assessment predominate.

Following this background, discussion shifts to the development of a communicative test of reading and language use for Classical Greek, to be used with international students. An outline of tests of Reading and Language use of Classical Greek at CEFR levels A1 and A2 is provided, illustrating how curriculum development adheres to communicative CEFR principles. The two tests have been developed so that, following trialling, they may be calibrated together to a single CEFR-linked scale.

Uptake of Classical Greek as a subject in the school curriculum

Classical Greek (or ‘Ancient Greek’) remains a key feature of many education systems. Besides being a compulsory secondary education subject in Greece, it is quite widely taught in many countries in Europe and around the world. This section briefly explores its reach.

In Italy, Classical Greek is a compulsory subject for the ‘Liceo Classico’ high schools (ages 14–19) and an estimated 6.7 percent of Italian students study Classical Greek over a period of five years (statista, 2021).

In the Netherlands, all classical secondary school ‘gymnasia’ students study Latin and Classical Greek for three years (ages 12–15) with an average of two to three teaching hours a week per language. Students can then opt to focus on one of the two languages for another three years, with an average of four to six teaching hours a week (van Bommel, Reference Van Bommel2016).

In Germany, Greek is taught in many ‘gymnasia’ (grammar schools). Additionally, students aged 14 and over in 200 high schools are able to opt to learn Classical Greek as a third foreign language (Chrysopoulos, Reference Chrysopoulos2016; fonien, 2016).

In the UK, Classical Greek is taught at elite secondary schools, with a small, if consistent, number of candidates each year sitting Year 11 GCSEs and Year 13 A levels – see Taylor (Reference Taylor and Morwood2003) for a discussion.

Classical Greek is also taught in Uruguay, where there is a substantial Greek community (ellines, 2018).

While the study of Classical Greek is viewed in some quarters as having little relevance to modern society, other scholars are more positive, discussing how the uptake of Classical Greek may be furthered (Foster, Reference Foster2018). Gibbs (Reference Gibbs and Morwood2003), for example, writes about the outlook for the teaching of Classics being ‘more auspicious’ than in previous decades. Bracke (Reference Bracke2015) discusses the teaching of the subject in primary schools in Wales. Hunt (Reference Hunt, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) describes movements to increase – with some success – the uptake of Classics in UK schools in the period 2010–15. Holmes-Henderson et al. (Reference Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) review ways of increasing the uptake and reach of Classics.

Teaching Methods and Materials

Teaching methods for classical languages such as Latin and Greek have been typically traditional – largely grammar translation (Nielson, Reference Nielson2018). Under such a methodology, the majority of the instruction is conducted through the medium of the students’ first language, where the focus is on reading texts, or ‘more typically, translating them’ (Gruber-Miller, Reference Gruber-Miller and Gruber-Miller2006).

In contrast, the essence of a ‘communicative’ approach to language teaching (e.g. Richards & Rodgers, Reference Richards and Rodgers2014) may be summarised as a focus on communication, rather than simply on form, and on the communicative needs of learners, rather than solely focusing on linguistic systems such as grammar.

Given that an accepted tenet of the teaching of modern languages is that communication and language use should be at the forefront of any pedagogical approach, it is instructive to consider why grammar translation as a methodology predominates in the field of Classics education. In the UK, where classical languages are taught in a comparatively small number of elite schools, subjects such as Latin and Classical Greek have been considered essentially tests of intellectual ability. In many instances, the teaching of Classical Greek is limited to analysing the original text in terms of grammar, syntax and form – with the focus being on translating the text in students’ L1 and engaging in a philological analysis. In this context, grammar translation as a toolkit for language study and analysis has been viewed as the vehicle to access meaning and to establish understanding of the written message. Against this backdrop – and with the aim of the teaching of modern foreign languages being communication – it is perhaps not surprising that teaching methods underpinning classical and modern languages have diverged. Nonetheless, a strong call is currently being made that, if the teaching of classical languages is to have a degree of relevance in the modern world, and for students to want to study them, more communicative-focused approaches to language learning and teaching need to be adopted. This argument is exemplified in the volume by Lloyd & Hunt (Reference Lloyd and Hunt2021), where the case for communicative approaches to the teaching of classical languages is clearly made, and which resonates strongly through the work of many educators and practitioners, a number of whom are cited below.

The lack of a focus on communicative competence has contributed to making the teaching of Classics cognitively rather demanding and this has led to a preponderance of dull, dry teaching materials and examinations, which bear little relevance to any form of communication and so have limited relevance to the learner; see e.g. Taylor (Reference Taylor and Morwood2003). Gruber-Miller (Reference Gruber-Miller and Gruber-Miller2006), on the issue of communicative competence, argues that if grammar is taught to the exclusion of communication skills, the result is students who have ‘a limited ability to comprehend and produce complex discourse fluently and accurately’.

Major (Reference Major2018) argues in a similar vein in his discussion of the Standards for Classical Language Learning (2017) in the USA, a document promoting the teaching of classical languages for all age groups and educational levels. Given that a major aim of the Standards is explicitly stated as communication, Major (Reference Major2018), summarising much that is deficient with relation to the dominant approaches and pedagogical resources for teaching Classical Greek, states:

Greek language teaching and pedagogical support materials are woefully out of sync with interest in the language outside the academy (Major, Reference Major2018, p.55).

Major (Reference Major2018) views the Standards for Classical Language Learning (2017) as being a force for helping to reorient the priorities and focuses of Greek language classes in the USA in ways that ‘both correspond to broader interest and result in improved language comprehension’ (Major, Reference Major2018, p.55).

With reference to the ‘broader interest’ issue alluded to above, it is interesting to note that while modern authors rarely write in Classical Greek, there are instances of modern-day attempts to further the reach of Classical Greek: Jan Křesadlo has written poetry and prose in a Classical Greek style, and versions of Harry Potter and Asterix are also available in Classical Greek. This resonates with Pettersson & Rosengren's (Reference Pettersson, Rosengren, Lloyd and Hunt2021) work in attempting to increase learner interest in Latin by creating modern resources in Latin.

There has been, it should nonetheless be noted, some innovation in the teaching of Classical Greek. Moore (Reference Moore2013), for example, outlines the use of song in the Greek classroom and how this may be used to motivate student interest. Bayerle (Reference Bayerle2013) describes the use of team-based learning to generate interest and activity in his Classical Greek classes. Dvorsky-Rohner (Reference Dvorsky-Rohner2008) describes the use of gaming exercises and strategies to engage and motivate learners of Classical Greek. Hill (Reference Hill, Lloyd and Hunt2021) outlines the operation of a ‘conventiculum’ – all-day immersion activities – in Classical Greek.

Assessment

In the field of modern languages, mirroring the changes in the approaches to teaching, assessment has seen similar shifts: with moves to more communicative and relevant forms of assessment. Paltridge (Reference Paltridge1992) frames one of the key aims of communicative language testing as measuring how well a test taker is able to perform ‘real life’ language tasks, or activities. As Bachman and Palmer (Reference Bachman and Palmer2010) outline, the validity of a language test is predicated on how much test scores reflect what test takers can do in a language. The corollary of this is that assessment tasks will bear some relevance to the real world, and not be solely tests of grammar.

As outlined above, the teaching of Classical Greek is gaining some momentum towards a more communicative outlook. In contrast, assessment remains very traditional. An examination of the UK's A level Classical Greek examinations, for example, reveals a heavy focus on translation and the explication of grammatical rules. Assessment at college level also reflects a heavily analytical focus. Watanabe (2010), for example, describes a Greek standardised multiple-choice examination taken by students from 24 American colleges and universities. The college Greek examination outlined by Watanabe does not assess any ‘communicative constructs’ (Harding, Reference Harding2014), with all test items being discrete-point tests of the forms of noun cases, verb mood and tense, followed by similar questions on a short reading passage. The focus is purely on form (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2004); there is very little in the test which addresses any of the communicative forces outlined by Gruber-Miller (Reference Gruber-Miller and Gruber-Miller2006), or which have a place in the Standards for Classical Language Learning.

The Development of a Communicative Test of Reading and Language Use in Classical Greek

The test outlined below attempts to address some of the issues created by the lack of ‘communicativeness’ in existing Classical Greek tests. To be truly communicative, a test should ideally assess all language skills (see Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Myles and Marsden2019). As a first, albeit limited, step in this direction, the test developed assesses Reading and Language Use, with the test seen as a qualification suitable for young people or adults who intend to apply for higher education or professional employment. The test is intended to be calibrated to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) at levels A1 and A2. Development has taken place based on the CEFR manual (Council of Europe, 2001) with its detailed specifications guiding the development of tests, and addressing what is assessed, how performance is interpreted, and how comparisons in achievement may be made. The test has been developed by LanguageCert, an Ofqual-regulated awarding organisation offering globally-recognised language qualifications, whose purview is the assessment of modern languages in communicative contexts.

The following section presents an overview of the A1 and A2 level tests, with reference to test specifications covering both grammatical and functional aspects of communicative language ability. These specifications were produced over an extended period by a group of Classical Greek academics and teachers. The detailed set of specifications and associated official practice material is available in the LanguageCert Test of Classical Greek (LTCG) Qualification Handbook for the examination (LanguageCert, 2021). The examples provided below are drawn from this Qualification Handbook.

There are three key components to the test specifications, as per the CEFR Manual: reading and vocabulary subskills; topics; and grammatical/syntactic structures.

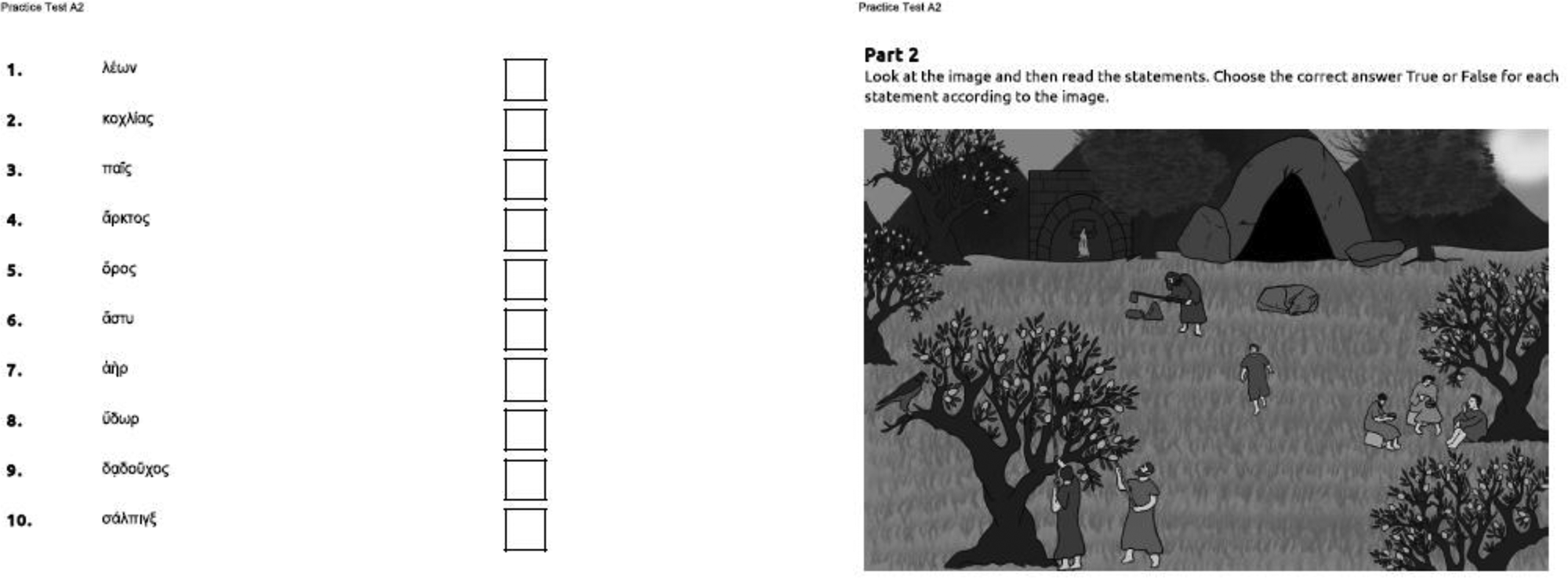

Reading is specified in terms of three components:

1. Reading subskills

2. Vocabulary range features

3. Text structure subskills

Figure 1 below presents a snapshot of these elements. The exemplars in the figures below are drawn from the A1 level test.

Figure 1. Reading skills (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

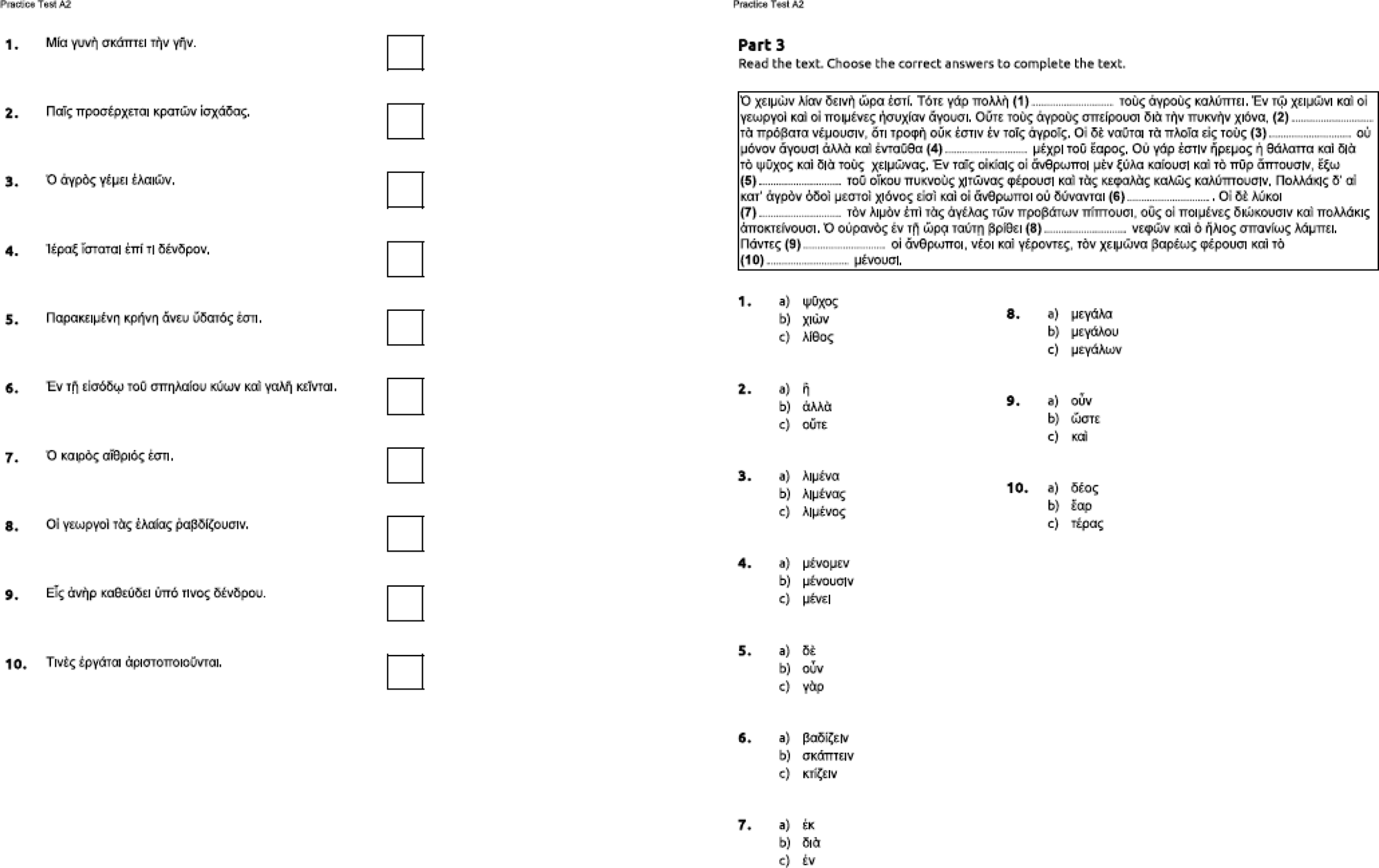

A range of topics are covered relevant to test takers in the modern world. Figure 2 presents a sample.

Figure 2. Topics (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

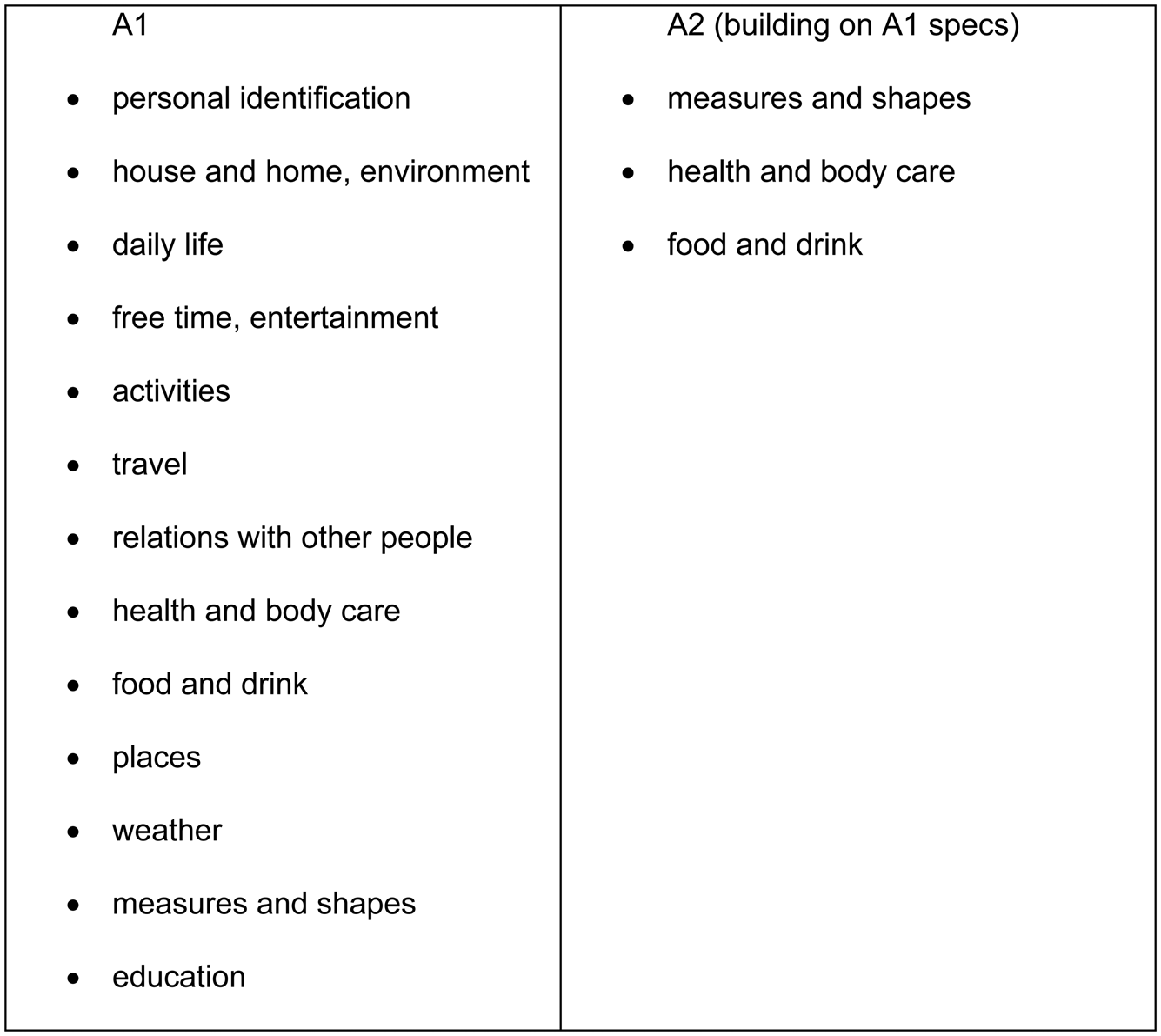

The most extensive part of the syllabus, nonetheless, as is perhaps to be expected, relates to the specification of grammatical, lexical and syntactic features. This came as a requirement for beginner levels in order to guide test takers and educators in organising their study prior to taking the exam. Key elements covered in the specifications are laid out in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Grammatical and syntactic categories (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

A fuller set of specification is provided in Appendices 1 and 2. These are presented in two columns, one for the A1 level test, and a second for the A2 level test (which subsumes the A1 component).

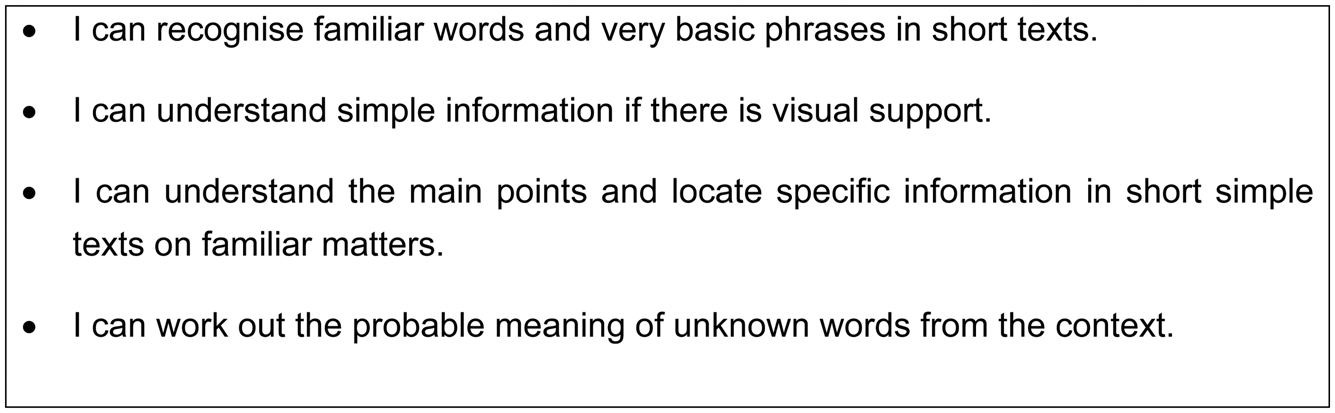

In line with Council of Europe principles and practice, CEFR-linked tests link with communicative ‘Can-do’ statements about language use. Figure 4 presents a sample.

Figure 4. Can-do statements (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

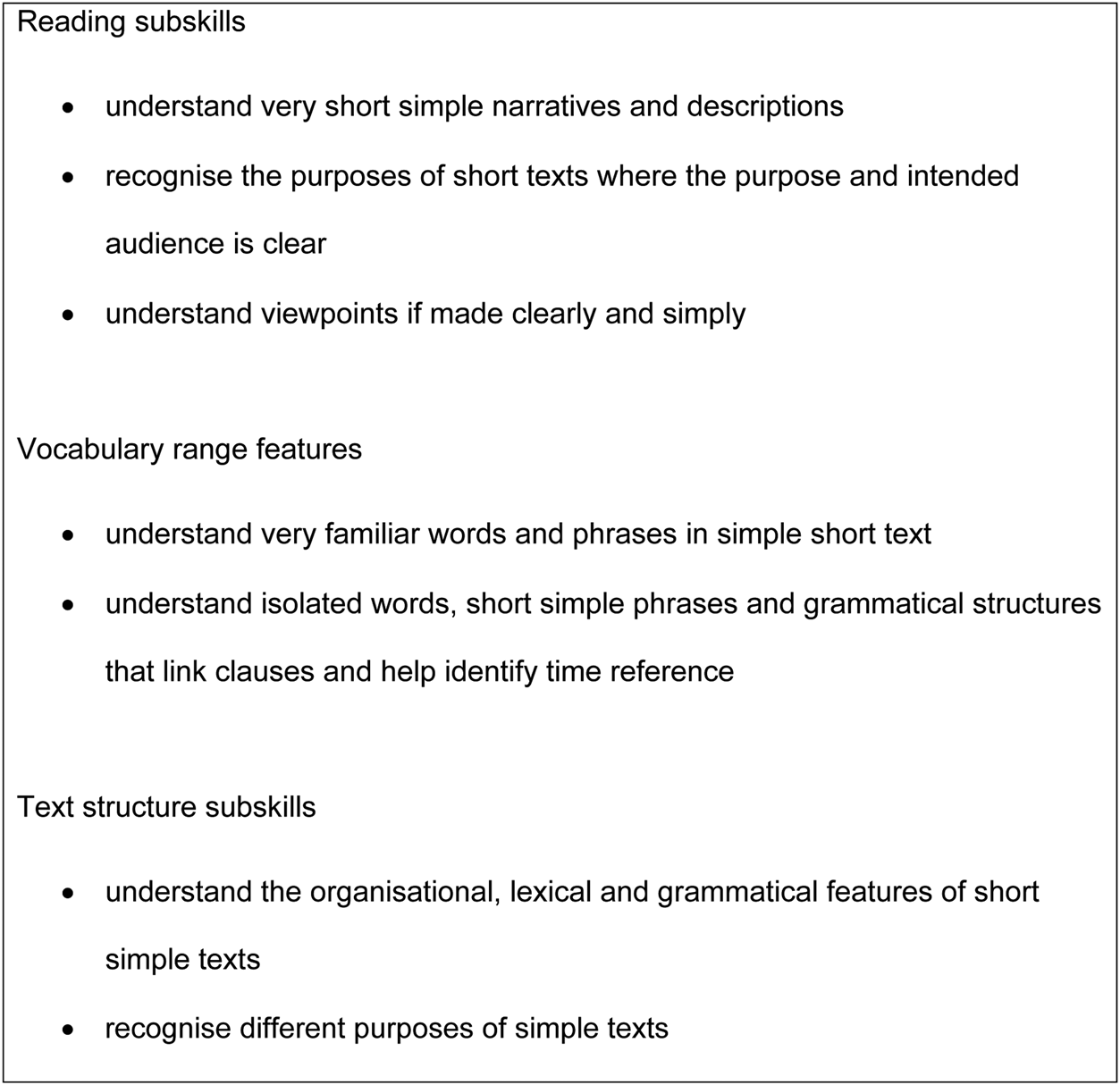

The use of ‘Can-do’ statements relates to the functional use of linguistic resources, and functional competence (Council of Europe, 2001). Tests aimed at lower-competency levels – as with the current A1 and A2 level tests – show an emphasis on finite elements of language form. That said, it can be seen how test parts go beyond a mere form analysis and require a fuller understanding of meaning conveyed. Part 2 focuses on relating meaning to a given image; in Parts 3 and 4, the textual nature of the assessment goes beyond the assessment of grammar and calls for inferencing meaning utilising cohesion and coherence devices of the transmitted message.

Test Components

The A1 and A2 tests both consist of four parts, each using distinct task types to assess specific sub-skills. Figure 5 elaborates.

Figure 5. Classical Greek task types (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

A sample paper for the A2 level Classical Greek test is provided in Appendix 4. Further detail and sample papers – official practice material – for both A1 and A2 levels are available at https://www.languagecert.org/en/language-exams/classical-greek/languagecert-test-of-classical-greek/languagecert-test-of-classical-greek-a1-ltcg-reading-and-language-use.

While the tests follow communicative principles and are a mixture of authentic and level-adapted materials, the tests at times draw on classical texts that embody the spirit of Greek writers and their works (see, for example, the University of Oxford's https://www.classics.ox.ac.uk/preliminary-examination-classics-and-english#/). This use of classical texts echoes the well-accepted practice of the use of literature in the language classroom (Daskalovska & Dimova, Reference Daskalovska and Dimova2012).

Trialling

To ensure quality and credibility, in any test development, trialling is a key element in the process which has to be conducted before a test may be formally offered. The trialling of the A1 and A2 level tests is planned for mid-2021 with each test being administered to a group of test takers identified as being at the appropriate level. The two tests have a common section so that they may be calibrated together, with the materials used in the two tests placed on a common difficulty scale. Test takers will also complete a set of ‘Can-do’ statements (a sample of which was presented in Figure 4 above), self-assessing their ability in Classical Greek. This will provide triangulated feedback to enable greater validity to be attached to the results obtained from the analysis and the calibration of the two tests together.

Concluding and Moving Forward

Following an examination of the background, history and approaches to the teaching of Classical Greek, the current paper has outlined the development of a new communicative test of reading and language use for Classical Greek aimed at test takers interested in obtaining a formal qualification in Classical Greek. The test has been developed in order to promote more contemporary approaches to communicative assessment within the context of the Council of Europe communicative principles for test design and for calibration to recognised standards. In this vein, the test entails a clear definition of specifications comprising both grammatical and functional elements. The paper has described how, with the advice and input of experts in the field, test specifications were developed and used to create a four-part examination which is now ready for trialling. Following the piloting, a follow-up paper will report on the validation of the trial tests and the creation of a preliminary common scale linked to the CEFR.

Appendix 1: LTCG Reading Subskills and Topic Specifications (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

Appendix 2: LTCG Grammar and Syntax Specifications (from LTCG Qualification Handbook)

Appendix 3: Sample Can-do Statements for CEFR Levels A1 and A2

Appendix 4: A2 Classical Greek Sample Paper