Introduction

The Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program is a Consortium of nearly 60 academic medical research centers across the USA funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) within the National Institutes of Health. Over $500 million is spent annually to support the program’s infrastructure and mission to accelerate the translation of clinical research intro practice and to improve the health of Americans [1]. Individual CTSA Program hubs provide an integrated research and training environment for translational science and catalyze the development, demonstration, and dissemination of methods and technologies that improve research efficiency and ultimately the population impact of health innovation [2].

Multisite clinical trials play a critical role in the translation of medical innovation to practice. Efficient mechanisms for planning and completing multisite trials are major unsolved problems in translational medicine. One of NCATS’ stated strategic goals is to “enable efficient clinical hypothesis generation and testing, facilitate participant recruitment for research, and enable straightforward cross-comparison of data sets” [3]. In response to this charge, the Accrual to Clinical Trials (ACT) Network was funded by NCATS to develop a federated clinical informatics data network of medical research sites across the CTSA Program Consortium [Reference Visweswaran4]. The network aims to support participant accrual to multisite clinical trials by improving cohort discovery and trial design when inclusion and exclusion criteria and site selection are determined.

Through its “hub-and-spoke” structure, the CTSA Program Consortium provides a natural network for promoting the spread and uptake of new clinical and translational innovation and research methods to improve healthcare delivery and health outcomes [5]. As noted in the NCATS Strategic Plan [3]: “CTSA hubs are expected to develop and demonstrate solutions to translational roadblocks individually, as groups of hubs, or as a network whole; in all cases, dissemination of successful solutions throughout the network, and to the translational research community as a whole, is an explicit goal and expectation” [5]. Collaborative Innovation awards aim to financially support the dissemination of validated solutions developed at one hub to other hubs and to test innovations in different hub settings and adapt the innovations for further dissemination within and outside the CTSA Program Consortium [6]. To date, the science of dissemination across the Consortium – including, understanding factors affecting speed of diffusion and characteristics of CTSA hubs as institutional adopters and local disseminators of translational research innovation – has been understudied.

Dissemination of the ACT Network among CTSA Program hubs began January 2018. Its dissemination represents a natural experiment for understanding the diffusion and national scale-up and spread of a clinical informatics innovation among academic medical institutions in the USA. This paper focuses on lessons learned during the CTSA hub dissemination and adoption process. Our intent is to elucidate how we operationalized dissemination of the ACT Network and stimulate dialog on potentially effective models and strategies for other teams disseminating research innovation across the CTSA Program Consortium. In addition to presenting current-state learning, we identify areas for further study.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive mixed-methods program evaluation was conducted to characterize the first 18 months of national dissemination of the ACT Network for the time period January 1, 2018–July 1, 2019.

Dissemination Product: The ACT Network

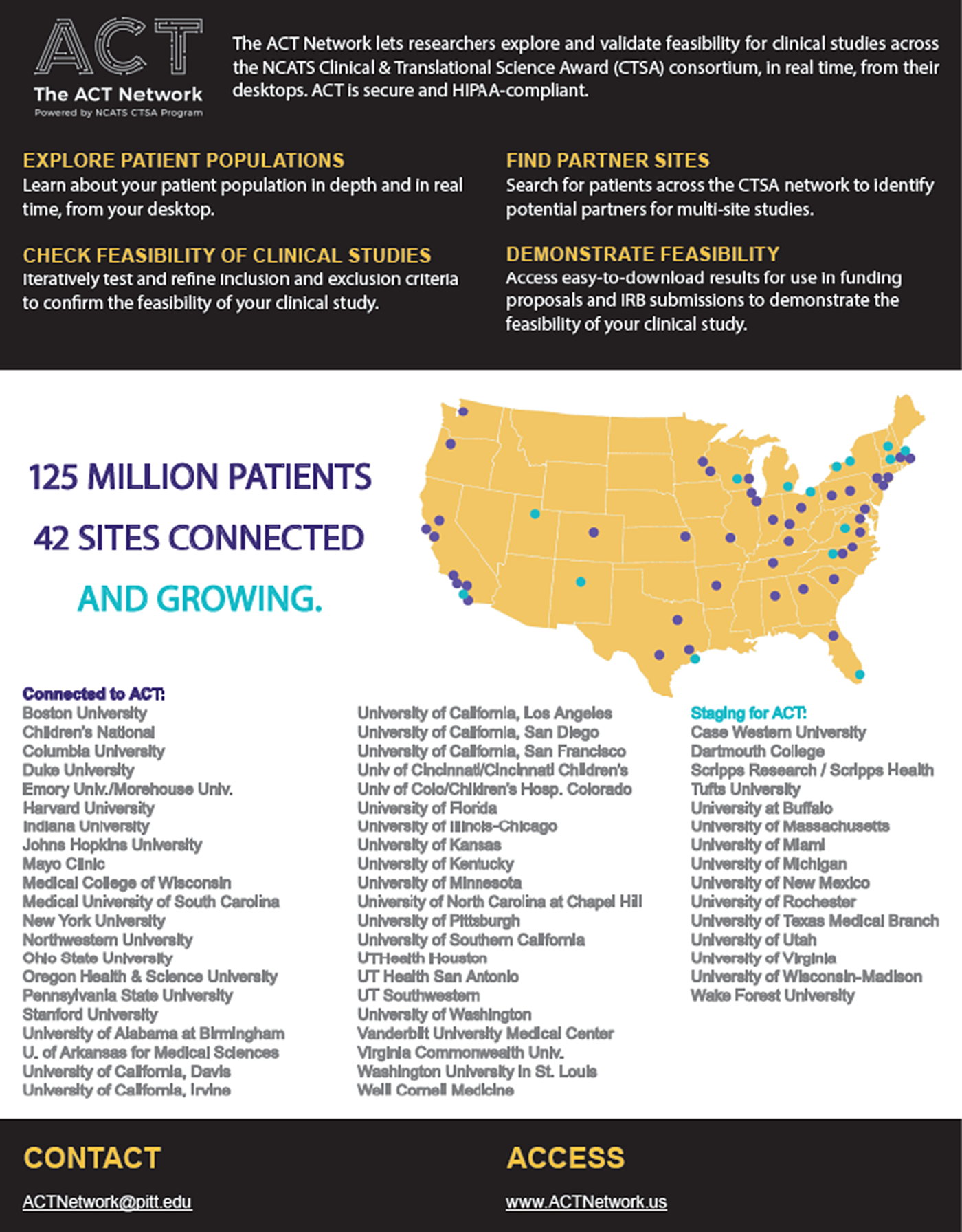

Fig. 1 shows the geographic reach of the CTSA hubs participating in the ACT Network. The ACT Network data platform is a HIPAA-compliant clinical informatics tool for clinical researchers to query de-identified electronic health record (EHR) data and iteratively explore and validate cohort feasibility in real time at their desktops [Reference Visweswaran4]. Investigators can identify potential partners for multisite studies and support study feasibility for funding proposals and IRB submission. The network has created governance and regulatory frameworks and a common data model to harmonize EHR data across institutions.

Fig. 1. The ACT Network (as of July 1, 2019).

The network uses widely adopted informatics tools: Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Beside (i2b2) data repositories linked by the Shared Health Research Information Network (SHRINE) platform [Reference Weber7,Reference Murphy8]. SHRINE provides a federated query and response system that enables investigators to query EHR data housed in i2b2 repositories across multiple independent institutions [Reference Natter9,10]. For the ACT Network, new functionality in SHRINE was developed that supports a true hub and spoke network topology, eases network setup and management, enables a distributed data steward model, betters error reporting for users, and improves administrative reporting.

Dissemination Audience: The CTSA Consortium and Local Clinical Investigators

The ACT Network is being disseminated in partnership with 57 CTSA hubs representing nearly 100% of the CTSA Program Consortium. Each CTSA hub serves a variety of academic clinical and translational researchers extending reach to 100s and 1,000s of investigators and research staff per hub.

Centralized Dissemination Responsibility: ACT Network Project Team

The ACT Network project team is a national multidisciplinary consortium comprised of 40 individuals representing 23 CTSA institutions and organized into 5 workgroups: Data Governance, Regulatory, Technology, Data Harmonization, and Dissemination and Evaluation (see Online Supplement for organizational structure). The Executive Committee includes work group leads (or co-leads), NCATS sponsorship, and a national project manager. The committee meets biweekly to share progress against annual tasks and milestones, to discuss cross-work group priorities, for example, technology rollouts or release of updated governance documentation.

The Dissemination and Evaluation workgroup meets weekly to discuss operational activities of the dissemination launch strategy in addition to the process for evaluating the ACT tool and its usage across the CTSA Consortium. A full-time communications profession (LL) and project management professional (ES) are dedicated to the project. This work group sought regular strategic input from a Dissemination Advisory Board comprised of experts in dissemination research and practice; marketing; and in pharmaceutical and health informatics commercialization (see Online Supplement).

De-Centralized Dissemination Responsibility: CTSA Hubs

The ACT Governance document prescribes local team roles, including site lead, site operations coordinator, data steward, and dissemination lead (see Online Supplement). Each CTSA hub received funding to technically configure a local i2b2 data instance and join the ACT-specific SHRINE network, that is, technical readiness for dissemination. Each hub then received $25,000 annually to sustain their data node and support local outreach and user support.

Conceptual Framework

ACT launch and dissemination strategies were based on the PCORI Dissemination and Implementation Framework [11] and systematic application of diffusion of innovation theory for accelerating the adoption of biomedical interventions and technologies by individuals and institutions [Reference Dearing and Cox12–Reference Rogers and Rogers16]. Diffusion theory rests on the established fact that people typically learn of innovations through mediated channels of communication but then turn to trusted or expert interpersonal sources for advice about whether to adopt or not. ACT dissemination was conceptualized as a two-stage adoption process. The first stage of dissemination and implementation is the acquisition and activation of CTSA hub sites (i.e., formation of the data network and dissemination “distribution channel”). The second stage is the acquisition and activation of local clinical investigators using the data network (i.e., network “customers” and “end users”). Table 1 summarizes assumptions and strategies to engage stakeholders and to actively accelerate the dissemination and adoption of the ACT Network among CTSA hubs.

Table 1. The ACT Network dissemination strategy and hypotheses using diffusion of innovation theory as the conceptual framework

*Adapted from Dearing et al [Reference Dearing and Cox12]; Moore [Reference Moore14]; and Greenhalgh et al [Reference Greenhalgh15]

CTSA stands for Clinical Translational Science Award; NCATS for the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, National Institutes of Health

Dissemination Materials and Activities

Communication included mass media and interpersonal channels. For example, mass communication materials included a monthly newsletter, short quick-start training videos, and adaptable materials for use at the local CTSA level (e.g., sample messaging and graphics). A dissemination kickoff call with each CTSA hub team was held and the central ACT team served a customer relationship management role interacting frequently with hubs to support them through the dissemination planning process. Materials, including the website, were co-branded to promote peer-to-peer sharing within shared institutions.

Evaluation Methods

This evaluation reports on dissemination findings for sites participating in the network as of July 1, 2019 (n = 48 CTSA hubs) and summarizes learning for the first stage of adoption: acquisition and activation of CTSA hubs. Unless where noted, IRB approval was not required because the evaluation project was carried out as quality assurance and did not meet the definition of research per the Department of Health and Human Services regulations. Mixed-methods (grouped by diffusion element) were used to assess dissemination processes and quality of activities.

Adoption process

Dissemination team members (LL, EM) created an Excel database to track dates that local CTSA hubs or the central ACT Network team completed an adoption stage and/or dissemination milestone activity. Stages of adoption were (1) Governance Agreement: Initiated; (2) Governance Agreement: Completed; (3) Technical Readiness: Initiated; (4) Technical Readiness: Completed, (5) Dissemination: Planning Initiated; (6) Dissemination: website/URL ready; and (7) Dissemination: Local Launch. Primary analysis focuses on the dissemination process (stages 4 and onward). The Online Supplement provides additional Kaplan–Meier curves that pertain to the adoption stages that preceded dissemination (stages 1–3).

Dissemination activity milestones included (a) date the central ACT dissemination team sent an email invitation to each CTSA site to initiate local dissemination planning; (b) date CTSA teams participated in a kickoff conference call; (c) date the ACT dissemination team sent each CTSA site a dissemination readiness checklist for the site to complete and return electronically; (d) date the CTSA site returned their completed dissemination readiness checklist; (e) date the ACT dissemination team delivered a website/URL to each CTSA site that allowed end user at that site to directly access the ACT Network; and (f) date the CTSA first launched the ACT Network, either locally or publicly.

Kaplan–Meier curves were used to analyze time intervals between date of email invitation to initiate local dissemination and date of first launch and for two dissemination subphases: (1) date of email invitation to date of the hub’s kickoff conference call and (2) receipt of the dissemination readiness checklist to date a functional local website/URL was available for end users to access the ACT Network. The median number of days and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for each curve. Fitted loglogistic curves were predicted and plotted for the data. For CTSA hubs that launched the ACT Network locally, a histogram was used to visualize the time relationship between the date a functional website/URL was ready and the date of first launch.

Data from the date-tracking spreadsheet were used to categorize and assess the duration of dissemination subactivities by locus of responsibility: centralized (national ACT Team); de-centralized (local CTSA hub); and parallel activity. Based on continuous process improvement feedback from CTSA hubs, adaptations were made to streamline and integrate dissemination readiness with technical readiness work processes. The log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan–Meier curves between sites launching using the original dissemination planning process (phase A) versus improved processes (phase B).

Stata/SE 14.2 was used for graphical display and descriptive analysis of the date-tracking data and for statistical comparison (College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

For purposes of understanding sites’ experiences with ACT implementation, two evaluators (HAP, JH) conducted interviews with early institutional adopters of ACT. Interviews took place from December 2018 to April 2019. Semi-structured interviews took place by phone, which lasted approximately a half-hour. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by a member of the research team. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved study activities. Transcripts were analyzed for common themes.

Communication

Mass communication evaluation included longitudinal tracking of open and click-through rates for the monthly ACT Newsletter and comparison to higher education and health professional industry averages reported by Constant Contact®. Frequency of interpersonal communication between the ACT Network dissemination team (LL) and each CTSA hub was tracked from date of technical readiness to date of first launch and categorized by channel: WebEx, telephone, email. Descriptive statistics were performed to estimate the median (IQR) email exchange rate per CTSA hub.

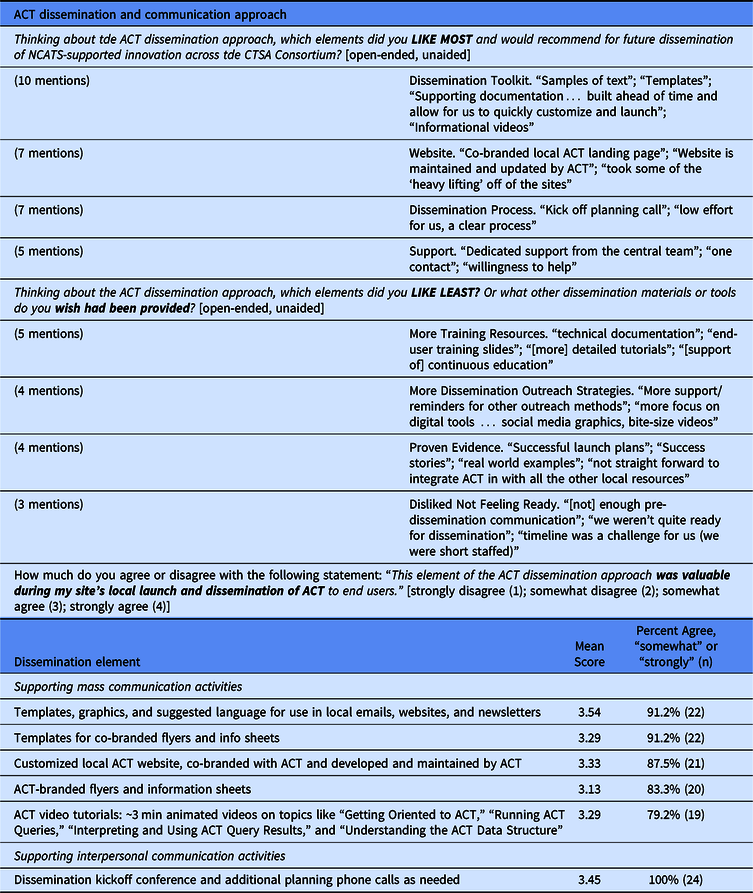

An internet-based survey was administered to the dissemination point person at each CTSA hub that had achieved local launch as of October 1, 2019 (77% response rate, 24 out of 33 CTSA hubs) to ascertain blinded feedback on ACT’s dissemination approach and communication materials. Three questions were open-ended and responses were qualitatively analyzed for common themes. There was one six-part close-ended question asking respondents to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed (on a four-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) that each of six different dissemination elements were valuable to their site’s local launch. An evaluator (AS) calculated mean scores and the number and percent of respondents who indicated that they “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that an element was valuable.

A dissemination team member (LL) solicited feedback from CTSA hub communicators during the September 19, 2019 CLIC (Center for Leading Innovation & Collaboration) Quarterly Communications call. The purpose of CLIC is to serve the CTSA Program through coordination, transparent communication and to make the work and accomplishments of the CTSA Program visible to all stakeholders. Open-ended questions included “how did you use the communication materials?”; “what are your thoughts about the customizable toolkit approach?”; and “what other tools or resources can help, when launching NCATS-funded innovation at individual CTSA hubs?” Notes were taken to record participants’ responses and analyzed for common themes.

Innovation

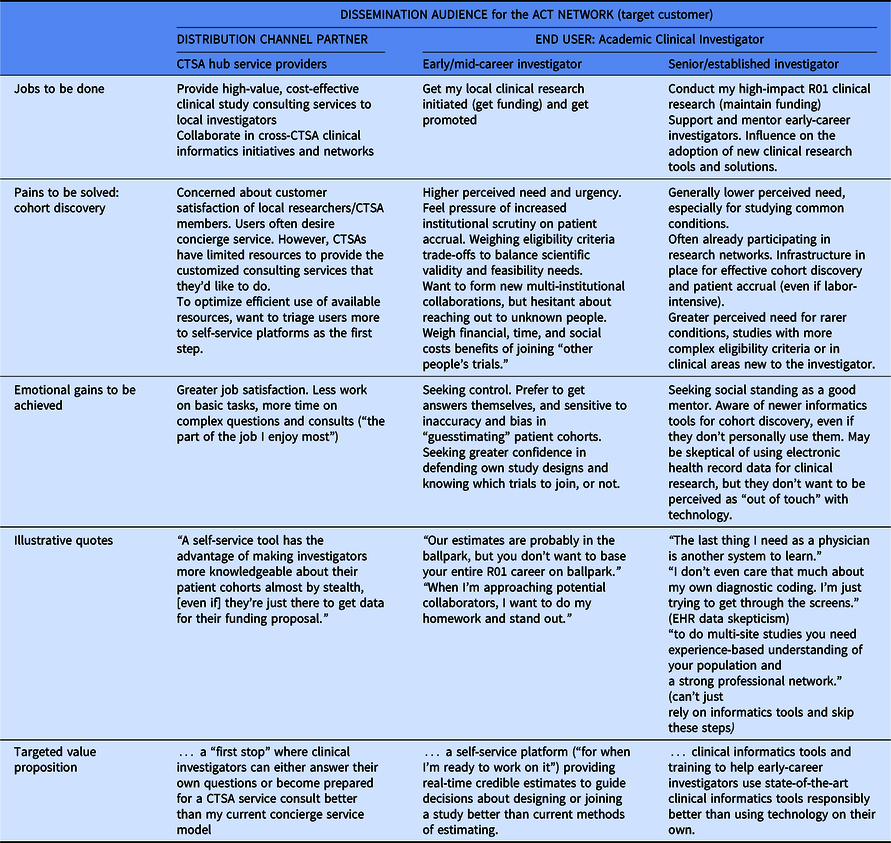

In-depth interviews were conducted by dissemination team members (LL, EM) among a convenience sample of CTSA stakeholders and clinical investigators to refine dissemination messaging and communication of the ACT Network’s value proposition. Interviews were conducted as part of the 5-week I-Corps@NCATS training program (September–October 2018) hosted by the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center [Reference Nearing17]. Interview methods and questions followed the I-Corp™ customer discovery process and elicited understanding of the most critical jobs-to-be done by stakeholders and the greatest pains (problems) to be solved, and gains (motivations) to be achieved through cohort discovery [Reference Osterwalder18,Reference Sattell19]. Notes were taken to record participants’ responses and analyzed for common themes.

Social setting

Activities engaging the CTSA Program Consortium at the system-level, for example, presentation at the CTSA Director meetings, were catalogued. NCATS communication to CTSA hubs concerning the ACT Network was monitored to assess messaging.

Results

Adoption Process

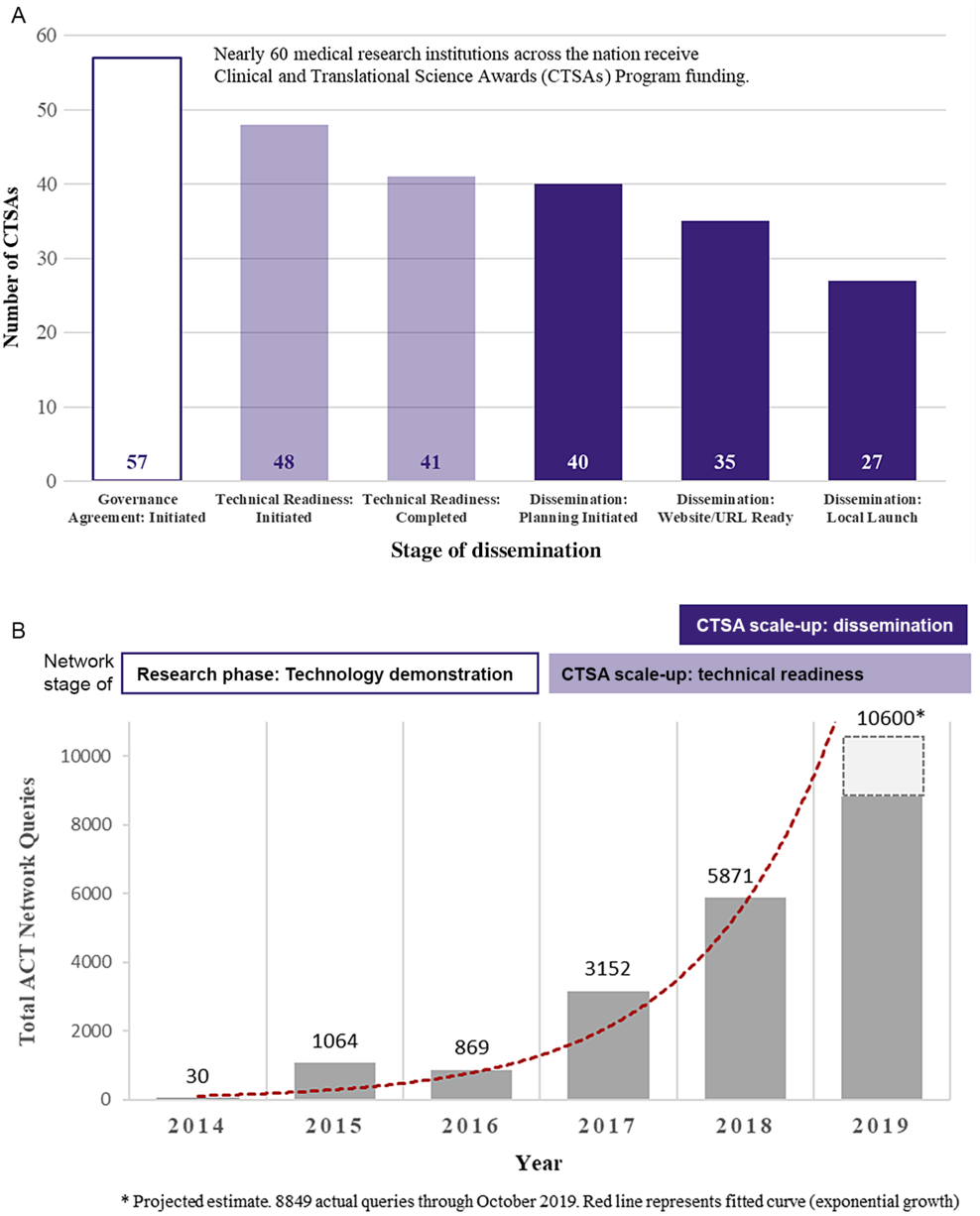

Fig. 2 presents the scale-up of the ACT Network among CTSA Programs by stage of dissemination (Fig. 2A) and the exponential growth in network queries over time (Fig. 2B). As of July 1, 2019, 41 CTSAs had achieved technical readiness, that is, gone live on the national production network. Among CTSAs achieving technical readiness, 66% (27 out of 41) had launched the tool to local users. The median time from technical readiness to local launch was 154 days (IQR: 87–225 days). Eight CTSAs were planning to disseminate the platform locally after the July 1, 2019 cutoff date. One CTSA decided to achieve technical readiness for multiple clinical data nodes at their hub before initiating local dissemination. Five CTSAs share clinical informatics data with the ACT Network but have deferred local dissemination given competing priorities and/or until evidence of utility (i.e., social proof).

Fig. 2. Scale-up and spread of the ACT Network among CTSA Programs. A. Institutional adoption (number of CTSAs) by stage (as of July 1, 2019). B. ACT Network usage (number of queries) over time.

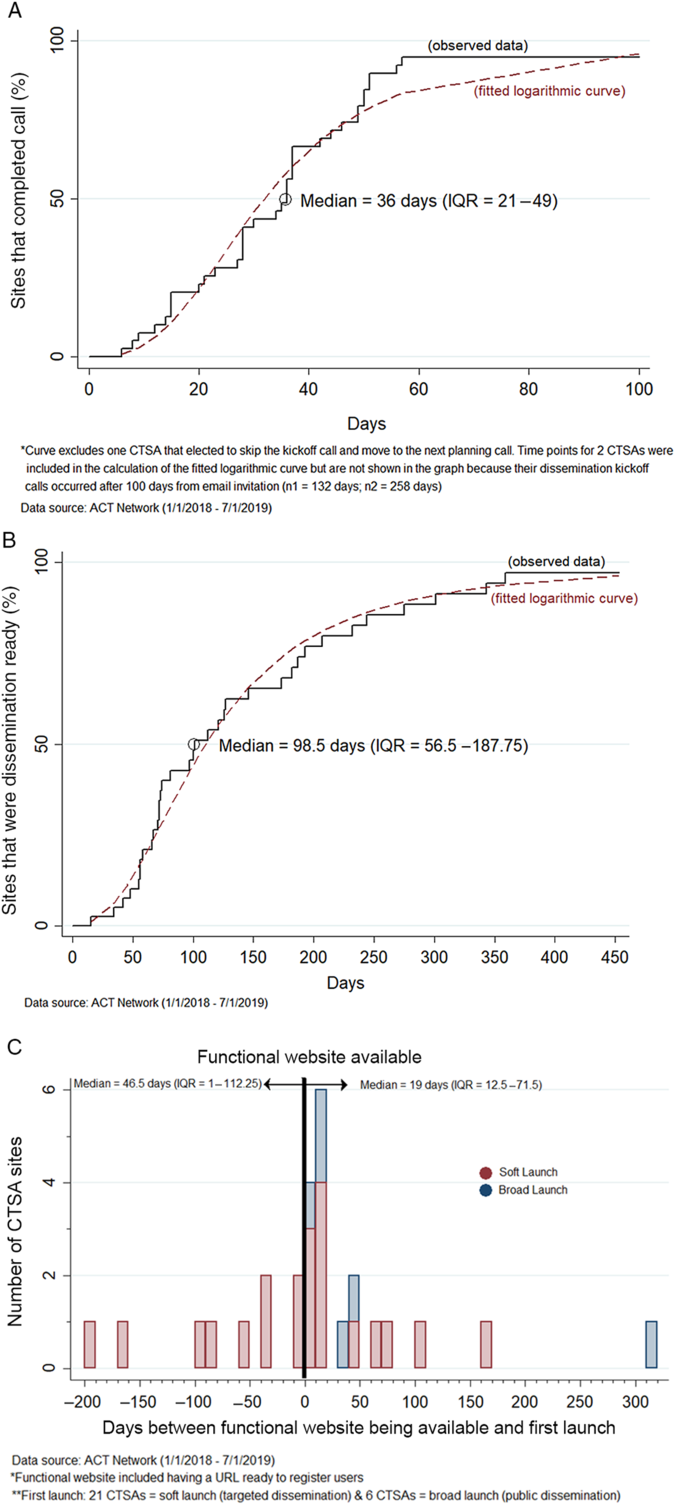

Fig. 3 presents the time-based analysis of the dissemination process. Fig. 3A shows the Kaplan–Meier curve for the time from invitation to initiate local dissemination to date of the team kickoff conference call (n = 40 CTSAs). The median time to the kickoff conference call was 36 days (IQR: 21–49 days). Fig. 3B shows the Kaplan–Meier curve for the time from the date the dissemination readiness checklist was emailed to the site to the date the local website/URL was functional allowing end users to directly access the network (n = 40 CTSAs). The median time from checklist to dissemination readiness was 99 days (IQR: 57–188 days).

Fig. 3. Time-based analysis of three different stages of the ACT dissemination process. A. Time from the date the invitation to initiate local dissemination planning was emailed to the CTSA (following technical readiness) to the date of the team kickoff conference call (n = 40 CTSAs). B. Time from the date the dissemination readiness checklist was emailed to the CTSA to the date the local website/URL was functional (dissemination ready) (n = 40 CTSAs). C. Time between the date the local website/URL was functional and the date the CTSA launched the ACT Network locally (n = 27 CTSAs).

Fig. 3C is the histogram showing the time relationship between when the CTSA’s website/URL was functional and the date when they first launched the ACT Network locally (n = 27 CTSAs). Nine CTSA’s (33%) elected to soft-launch to local users prior to having the public-facing website functional. Soft-launch methods varied by CTSA and included piloting the network among a few target users to launching the network to internal CTSA support groups (mediators) that provide study design and recruitment services to clinical investigators. A minority of CTSAs (22%, 6 out of 27) initiated local dissemination via a broad launch to all membership.

Interviews with early-adopting CTSA sites (20 hub personnel at 9 institutions) elucidated training and technical support needs from data stewards and site operations team members. Most said the technology was not difficult to learn with a minimal amount of training. For many,

The most helpful thing [about training] was getting to know the people in the project, to know who and introduce myself; so they have a face to go with … building rapport. [clinical informatics professional, CTSA site]

Perceived need for training resources targeting clinical investigators varied by CTSA site.

When rolling out, we had researchers here look at it [some tech savvy and some not] and give us feedback to see if videos were appropriate and sufficient or if we needed to develop additional training. The feedback we got was that it was self-explanatory and didn’t feel additional training necessary. [clinical informatics professional, CTSA site]

Yes, the i2b2 interface is simple and we have clinical data navigators who can help the researchers … I still think it is important [to get training] on how to do complex queries, otherwise [people may be] using system in immature ways. [clinical informatics professional, CTSA site]

Communication

In terms of mass communication, the ACT Newsletter has a membership list of over 500 individuals representing CTSA principle investigators, clinical informatics leads, ACT data stewards and site operations coordinators, marketing/communication professionals and other stakeholders. Engagement with newsletter content has been relatively strong given industry norms for this communication channel. Mean open and click-through rates (e.g., to access new training videos) were consistently higher than higher education and health professional industry averages (open rate: 36% vs. 22% and 18%, respectively; and click-through rate: 20% vs. 8% and 7%, respectively). Analysis of interpersonal dissemination communication between the national ACT dissemination team and the 27 CTSA Program hubs who achieved local launch averaged showed 1 WebEx team kickoff, 1–2 follow-up phone calls, and 29 (IQR: 24–39) email communications per site.

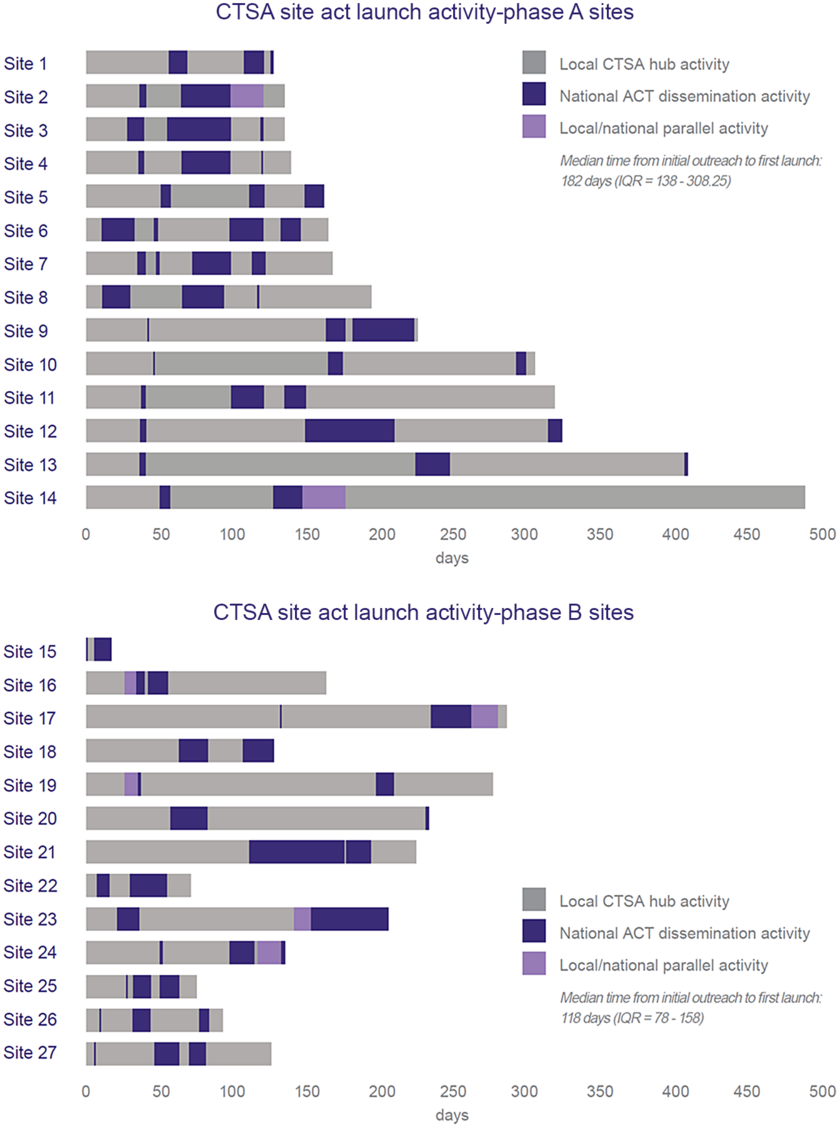

Fig. 4 shows the break down in time allocation on dissemination planning and preparation activities (points of interpersonal communication) between the local CTSA and national ACT team varied between CTSA hubs (n = 27 CTSAs). Sites were stratified into two groups: before (n = 14) and after (n = 13) dissemination process improvement changes were implemented. Quality improvement efforts were associated with a 64-day (35.2%) reduction in median time to local launch: 118 days versus 182 days (p = 0.0036).

Fig. 4. Comparison of the duration and locus of responsibility for dissemination planning activities by CTSA hub achieving local launch (as of July 1, 2019) (data show duration of dissemination readiness activities for CTSA hubs that launched the ACT Network to local users (n = 27 CTSAs). Sites are listed in order of launch date. Bar length represents time from technical readiness to launch and is subdivided based on locus of activity: centralized (ACT Team) versus de-centralized (CTSA hub). Phase A used original dissemination readiness processes. Phase B used improved processes based on quality improvement feedback. In Phase A, all sites had the same technical readiness date and joined the production network in unison. In Phase B, sites had varying technical readiness dates).

Table 2 summarizes survey feedback on the dissemination materials and approach used by the ACT Network. Overall, feedback on the dissemination process was positive. The items receiving consistently high value were the dissemination kickoff call, dissemination toolkit and co-branded, and centrally maintained local websites. Having dedicated support from the central team was critical. Areas for improvement focused on sustaining dissemination, including more training resources, success stories, and continued outreach strategies.

Table 2. CTSA site feedback on the dissemination and communication approach used by the ACT Network

Twenty-four CTSA respondents (77.4% survey response from among the 31 sites that have locally launched ACT through October 1, 2019)

Feedback from the CLIC quarterly communicators call was similar in nature. Two illustrative quotes were

The materials were very helpful; the project manager *could have* developed these materials independently but ACT was 1 of 30 other initiatives/programs so having these launch materials helped move ACT up in the queue. Local response to ACT has been positive but slow. The kickoff call was very helpful and having a full-time ACT communicator to support the process seems essential for a national launch like this. [communications professional, CTSA site]

need testimonials/faculty champions to encourage use post-launch. [communications professional, CTSA site]

Innovation

Table 3 summarizes feedback obtained from customer discovery interviews (n = 35) to understand how best to message and demonstrate two-sided value to both CTSA hub partners (n = 13), clinical investigators (n = 17), and other stakeholders involved in academic clinical trial research (n = 5).

Table 3. Summary of customer discovery learning

CTSA hub clinical trial support and service providers seek satisfied users of their services. For them, the ACT Network could provide a “first stop” where clinical investigators can either answer their own questions or become better prepared for a clinical trial service consult. Cohort discovery needs of clinical investigators varied by career stage. Early-career investigators felt the pain of increased institutional scrutiny on meeting patient accrual targets and timelines. For them, the ACT Network could provide a self-service platform for real-time credible estimates to guide decisions about designing or joining a study. Senior clinical investigators have an established track record and personal network for conducting cohort discovery, so this is a lower perceived need. Instead, the desire to be viewed as a good mentor was more salient and they did not want to be perceived as “out of touch” with technology. Based on these insights, we hypothesize that providing training to help early-career investigators use state-of-the-art clinical informatics tools responsibly (thereby alleviating the burden on individual senior investigators to provide this mentorship directly) would provide value.

Social Setting

NCATS publicly supported the ACT Network. The team was invited to present at the CTSA Principal Investigator (PI) Webinar and present in-person project updates at the 2018 and 2019 Fall and 2018 Spring CTSA Meetings reaching PIs and other CTSA hub leadership. At the 2018 Spring CTSA Meeting, the ACT team had a live demonstration table to showcase the platform. At the 2019 Spring CTSA Meeting, the ACT team presented at the Workforce Development Domain Task Force to seek feedback and explore the potential for adjacent value of the network for informatics training. The ACT Network dissemination team participates regularly in the quarterly CLIC-CTSA Communicators’ meeting and is mentioned regularly in the monthly CLIC newsletter to CTSA Program leadership.

However, NCATS has messaged that network participation is optional. In an email to CTSA PIs and administrators in June 2018, NCATS stated that it “views the ACT Network project as an exciting and innovative experiment … [however] NCATS is cognizant of the competing demands for hubs resources … [and] wants to clarify that participation by the hubs in the ACT Network is voluntary … and no criteria related to the participation in the ACT Network is used in the funding opportunity announcement.” As a result, some CTSA sites have stated “we want to be good citizens” but are unclear on the degree of local dissemination outreach that is expected by NCATS.

Discussion

The spread and uptake of the ACT Network demonstrates that the CTSA Program Consortium is an institutional network incentivized and primed to participate in the national dissemination and adoption of clinical and translational research innovation to improve healthcare delivery and health outcomes. Within 18 months, over 80% of the CTSA Consortium had joined the data network and two-thirds of CTSAs that had achieved technical readiness reached the first phase of adoption by launching the network to local users. Over 10,000 ACT Network queries are projected for 2019; and by 2020, nearly all CTSAs will have joined the network. The ACT Network adds to the armamentarium of NCATS-supported translational research tools adopted among CTSA hubs, namely, REDCap for data management, i2b2 informatics software, and SMART IRB Master Reliance Agreement enabling single IRB review [Reference Murphy20–Reference Cobb22]. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic evaluation of the diffusion process of a new translational research tool being actively disseminated across the CTSA Program Consortium of academic medical research centers.

Early dissemination findings are consistent with what diffusion theory predicted. We observed the classic S-shaped adoption curves demonstrating that institutional adoption is a time-based process. In our case, timing appears consistent with academic quarterly and semester workflows and pace of new program implementation. As we gained experience and CTSA hub feedback, we improved our dissemination planning and quick-start processes reducing time-to-launch by 35% (approximately 2 months). Feedback from CTSA hub partners underscored the criticality of interpersonal communication, both with the central ACT dissemination team and within CTSA hubs, in navigating the adoption process. Given competing priorities at the local CTSA hub level, the perceived value of reducing dissemination complexity (e.g., by including a kickoff planning call and dissemination readiness checklist; having a centrally supported website; and providing pre-developed messaging) was high and facilitated adoption. Efforts to support compatibility with local institutional systems (e.g., co-branded materials and websites) were also valued. Lastly, rapid institutional adoption was enabled by the CTSA Program’s social system in which cross-institutional collaboration and adoption of clinical informatics innovation is incentivized.

The spread and uptake of the ACT Network is an example of real-world adaptive dissemination. To sustain CTSA implementation and grow usage, the ACT Network is now moving beyond the first stage of CTSA institutional adoption to the next stage of dissemination and end user adoption and use. For this stage, demonstrating value and relative advantage for local users will be critical. The next wave of dissemination strategies are grounded in diffusion of innovation theory and based on CTSA hub partner feedback to date.

First, we are identifying success stories and seeking local faculty champions to demonstrate and provide the social proof of ACT’s utility and value. This is a critical evidentiary need necessary for “crossing the chasm” in technology adoption as adoption moves from early adopter/visionaries motivated by being “first movers” motivated by the technology itself to early majority/pragmatists who are motivated by “practicality” and evidence of utility [Reference Moore14]. In this context, it is important to show ACT’s value relative to a changing and dynamic competing alternative landscape, including other regional and national health data networks and technology solutions being used and adopted by CTSA Programs, such as PCORnet [Reference Fleurence23]), EPIC Slicer-Dicer tool and Cosmos Platform [Reference Bazzoli24,Reference DuVernay25], TriNetX [Reference Stapff and Hilderbrand26], and Leaf [Reference Dobbins27]. Selecting stories and messaging that are most relevant to early-career clinical investigators, the audience segment we have identified with the greatest perceived unmet need and readiness to adopt new informatics tools, appears warranted based on customer discovery insights. We are also exploring opportunities for providing adjacent value to meet other CTSA Program hub needs, such as developing and helping to spread platform-agnostic training and educational tools supporting cohort discovery. The i2b2 and SHRINE development teams are pursuing product upgrades to improve end user experience (i.e., further reduce perceived complexity). Lastly, as part of the CTSA Program social system, the ACT Network is building partnerships with other groups disseminating translational research innovation within the same ecosystem, such as, the CD2H (Clinical Data to Health) [28] and Trial Innovation Network [29,30] centers.

Based on our initial operational experience disseminating the ACT Network within the CTSA Program Consortium, we offer the following pragmatic considerations for others designing and planning for dissemination across the CTSA Consortium (see Box).

1. Conceptualize dissemination as a two-stage adoption process. This means demonstrating value and targeting dissemination strategies and materials for both CTSA hub service providers and clinical investigators. At the start of ACT dissemination, CTSA hubs had not planned how they would migrate from an informatics research team implementing ACT to a cross-disciplinary team disseminating ACT. To address this gap, we integrated dissemination readiness checklists earlier into the technical readiness process. Customer discovery, as taught in the I-Corps program [Reference Nearing17,Reference Sattell19] was also used to identify target segments and areas of most urgent unmet needs to focus value creation, including dissemination messaging. Ideally, designing-for-dissemination methods, such as I-Corps and the National Cancer Institute’s SPRINT program [Reference Chambers31] should be embraced early to inform technology development and sustainability [Reference Morrato32].

2. Engineer-in CTSA hub trial into the dissemination strategy. In retrospect, the strong preference by CTSA hubs to proceed with a “soft launch” of ACT before broad dissemination to local investigators is not unexpected given diffusion theory and “public beta testing” practices commonly used in the launch of software and digital technologies. Goals of trial included seeking feedback to refine internal workflows and to gather early user feedback and endorsement.

3. Embrace adaptive dissemination and the tech start-up world’s “get-keep-grow” philosophy to customer relationship management [Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur33]. In other words, sustained scale-up and spread is not “one and done” dissemination; instead, it requires continuous effort to keep CTSA hubs and users engaged. Dissemination must remain responsive to changing external environments and customer needs. As such, sustained activity should be anticipated and budgeted accordingly given high demand for interpersonal communication and outreach.

Box. Key considerations for disseminating innovation across the CTSA Consortium

-

1. Conceptualize dissemination as a two-stage adoption process. This means demonstrating value and targeting dissemination strategies and materials for both CTSA hubs (service providers) and clinical investigators (end users).

-

2. Engineer-in CTSA hub trial into the dissemination strategy. The goals of trial include seeking feedback to refine internal workflows and gathering early user feedback and endorsement. These practices reflect diffusion of innovation theory and “public beta testing” practices commonly used in the launch of software and digital technologies.

-

3. Embrace adaptive dissemination and the tech start-up world’s “get-keep-grow” philosophy to customer relationship management. In other words, sustained scale-up and spread is not “one and done” dissemination; instead, it requires continuous effort to keep CTSA hubs and users engaged.

The scale-up and spread of translational research tools and workforce development programs across the CTSA Program Consortium is ripe for further research to advance the science of adaptation and translation. Future research direction can include developing a CTSA-specific Adaptome [Reference Chambers and Norton34] to describe and create a common data platform to systematically capture information about variations in the scale-up and spread of translational research innovation across CTSA institutions and contexts. This knowledge can guide translational research tool developers and the dissemination and implementation research communities engaged in the CTSA Program [Reference Ford35,Reference Brownson36].

In addition, because the CTSA Program Consortium is a dynamic complex system, lessons learned from systems theory, and its application in healthcare [Reference McDaniel, Lanham and Anderson37] and public health [Reference Leischow38], can also inform future research. This includes enabling a learning network by managing systems knowledge about scale-up, understanding the Consortium’s unique social networks, and developing methods for analyzing adoption behaviors and processes. The business-to-business (B2B) marketing literature is another relevant resource because it also focuses on the challenge of introducing new products-services into complex institutional entities involving multiple layers of decision-makers, adopters, and end users [Reference Anderson, Narus and Narayandas39]. For example, we might conceptualize the ACT team as the “manufacturer,” the CTSA hub “institution” as the top-level adopter, and individual researchers as the ultimate “consumers/end users”; with this framing, the ACT Network has developed a “distribution channel” [Reference Coughlan40] with the CTSA hub “institution” acting as a “retail intermediary.”

In summary, we describe the initial dissemination experience of the ACT Network and encourage dialog on effective models and strategies for disseminating translational research innovation across the CTSA Program Consortium. Limitations of the evaluation should be noted. First, it represents one case experience and findings may not be generalizable.

Second, the scope of the evaluation focused on CTSA hub dissemination from the time point of technical readiness define as going live on the production network. Kaplan–Meier figures are presented in the Online Supplement about the time-based analysis of the earlier stages of adoption: the governance agreement and technical readiness processes. The median time to complete (1) the governance agreement was 49 days (IQR: 23–134 days) and (2) technical readiness was 1,217 days (IQR: 1,126–1,217) for Phase A sites and was 477 days (IQR = 260–488) for Phase B sites. It should be noted, though, that the threefold increase in technical readiness for Phase A versus Phase B sites was affected by the fact that Phase A sites participated in early pilot development of the network, and there was a significant time lapse between NCATS proof-of-concept funding and dissemination funding when the production network was activated. Given the duration and variation in technical readiness timing, a root cause analysis would also be informative for accelerating the development and adoption of future informatics innovation. Further evaluation is also underway to understand the adoption process of clinical investigators and end users. Our aim is to leverage the Act Network as a learning collaboratory to advance the science of CTSA institutional uptake of innovation and improve its research efficiency and impact on health outcomes and healthcare delivery. The Network is primed for partnership-based embedded implementation research.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.505.

Acknowledgments

This project was in partnership with the CTSA Program Consortium and supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under CTSA Grant Numbers UL1TR001430, UL1TR001876, UL1TR001873, UL1TR002553, UL1TR002378, UL1TR002541, UL1TR002529, UL1 TR002377, UL1TR002373, UL1TR001450, UL1TR001445, UL1TR001422, UL1TR002733, UL1 TR002014, UL1TR003142, UL1TR003096, UL1TR003107, UL1TR001860, UL1TR001414, UL1TR001881, UL1TR001442, UL1TR001872, UL1TR002003, UL1TR002535, UL1TR001427, UL1TR002366, UL1TR001998, UL1TR002494, UL1TR002489, UL1TR001857, UL1TR001855, UL1TR000130, UL1 TR002645, UL1TR001105, UL1TR002319, UL1TR002243, UL1TR002649, and UL1TR002345. We acknowledge our data governance and informatics colleagues on the ACT Network Executive Committee whose leadership and support ensured technical readiness for dissemination was achieved: Nicholas R. Anderson, Dipti Ranganathan, Vincent S. D’Itri, Eric Mah, Douglas MacFadden, Shawn N. Murphy, and Shyam Visweswaran. We thank the members of our Dissemination Advisory Board for their wisdom and strategic input into our strategies and evaluation: Anne T. Coughlan, James W. Dearing, Deborah Goeken, Wayne Guerra, and Jerry D. Shelton.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest to report.