Dear Editor,

In 2017 our team published a meta-analysis on the health outcomes of offspring conceived from donor sperm.Reference Adams, Clark, Davies and de Lacey 1 At the time of this review, there were only eight studies that were eligible for inclusion, and only three qualified for meta-analysis,Reference Davies, Moore and Willson 2 – Reference Hoy, Venn, Halliday, Kovacs and Waalwyk 4 and only two studies provided data for each outcome analysis. Our review demonstrated the paucity of studies investigating the perinatal outcomes of sperm donation.

After identifying this gap in research, we undertook a population study comparing the perinatal outcomes for neonates conceived with donor sperm and those conceived spontaneously in the state of South Australia.Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 Furthermore, since the census date of the meta-analysis a further two studies have been published that also meet the criteria of our original review,Reference Huang, Song and Liao 6 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 and we believed it was important that we add these three studies (two by other authors and one by ourselves), to our meta-analysis to see if the original findings were either supported or refuted.

The original findings showed that; donor sperm neonates in comparison to naturally conceived neonates were not at increased risk of being born of low birth weight [risk ratio (RR): 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.86–1.25, P-value (P)=0.71, I2=0%]; preterm (RR: 0.91, CI: 0.75–1.12, P=0.38, I2=0%); or with increased incidences of birth defects (RR: 1.20, CI: 0.97–1.48, P=0.09, I2=57%).Reference Adams, Clark, Davies and de Lacey 1

The addition of the new studies allowed not only for an increase in the number of studies included in the meta-analysis conducted above but also for a larger range of perinatal outcomes. All data extraction and analysis followed the method described in our original review. The studies that were included in each meta-analysis are listed as reference numbers in superscript after each meta-analysis.

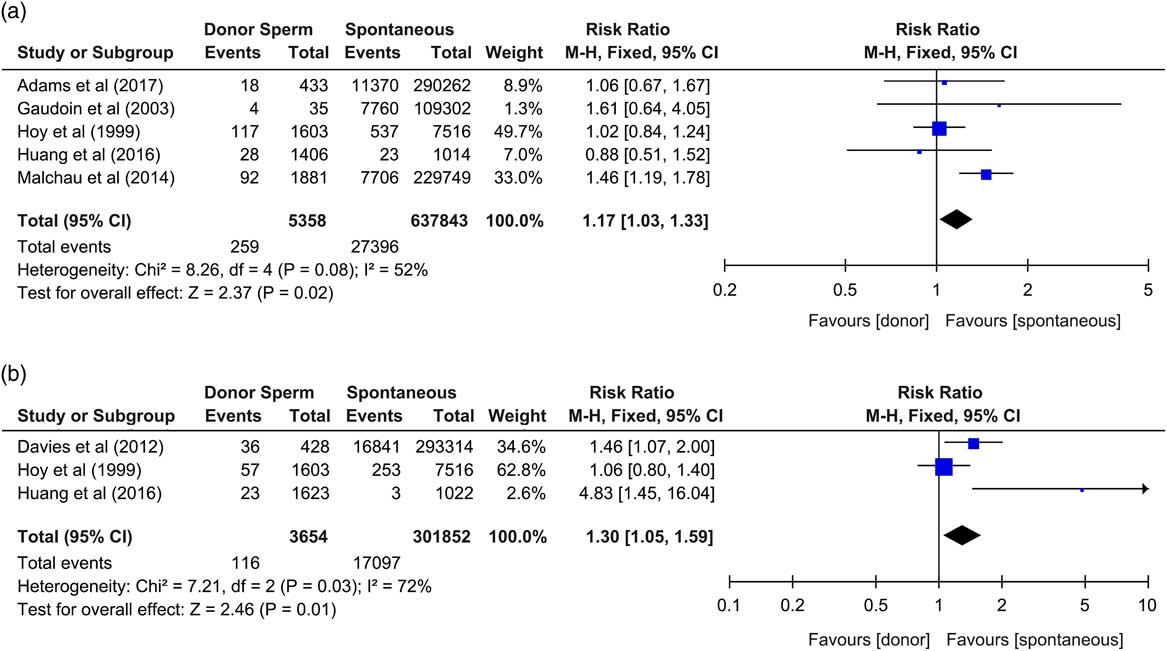

The updated meta-analysis has demonstrated that, in comparison to naturally conceived neonates, donor sperm neonates were at increased risk of being born of low birth weight (RR: 1.17, CI: 1.03–1.33, P=0.02, I2=52%),Reference Gaudoin, Dobbie and Finlayson 3 – Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 and with increased incidences of birth defects (RR: 1.30, CI: 1.05–1.59, P=0.01, I2=72%) (Fig. 1).Reference Davies, Moore and Willson 2 , Reference Hoy, Venn, Halliday, Kovacs and Waalwyk 4 , Reference Huang, Song and Liao 6 However, they were not at increased risk of being born preterm (RR: 1.05, CI: 0.91–1.21, P=0.47, I2=52%),Reference Gaudoin, Dobbie and Finlayson 3 – Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 very preterm (<32 weeks) (RR: 1.17, CI: 0.75–1.81, P=0.49, I2=0%),Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 very low birth weight (<1500 g) (RR: 1.22, CI: 0.76–1.97, P=0.4, I2=0%),Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 small for gestational age (birth weight <10th percentile) (RR: 1.19, CI: 0.99–1.42, P=0.06, I2=82%),Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 large for gestational age (birth weight>90th percentile) (RR: 1.04, CI: 0.86–1.38, P=0.71, I2=0%),Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 with altered perinatal mortality (RR: 0.93, CI: 0.59–1.45, P=0.74, I2=0%),Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 of lower mean birth weight (mean difference −12.5 g, CI: −32.03 to 7.02 g, P=0.21, I2=0%),Reference Gaudoin, Dobbie and Finlayson 3 , Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 – Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 or of lower mean gestational age (mean difference −0.02 weeks, CI: −0.10 to 0.05 weeks, P=0.55, I2=12%).Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7

Fig. 1 Forest plots of sperm donation outcomes. (a) Risk ratio for being born of low birth weight (<2500 g); (b) risk ratio for incidences of birth defects, neonates from donor sperm offspring v. spontaneous conceptions. CI, confidence interval.

Of the newly included studies, one appropriately stratified data into singletons v. multiple deliveries,Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 whereas another only analysed singletonsReference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 to remove confounding from multiple births. All three studies reported maternal ages, two of which adjusted for maternal age,Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 whereas the other had no significant difference between maternal ages of those conceiving with donor sperm v. spontaneous conception.Reference Huang, Song and Liao 6 Parity was appropriately adjusted for in two of the newly included studies.Reference Adams, Fernandez and Moore 5 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7

Caution should be taken when interpreting these results. Due to the heterogeneity present in some analysis, bias observed through funnel plot analysis, and the low number of studies included in some meta-analysis, more studies investigating perinatal outcomes in donor sperm-conceived neonates in comparison to spontaneously conceived counterparts in a systematic manner is required to improve our understanding of the effects of using donor sperm in assisted reproduction. Furthermore, the use of specific ovarian stimulation drugs such as clomiphene citrate during fertility treatment (including intrauterine insemination with donor sperm), is associated with increased incidences of poor neonatal outcomes.Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 , Reference Poon and Lian 8

Results showed that there was an increased risk of low birth weight, but not a concomitant increased risk of preterm delivery. We did not conduct a meta-analysis of data for obstetric outcomes, only neonatal outcomes, and therefore cannot comment on any correlation with early obstetric intervention or delivery methods such as caesarean section. However, some studies did report higher incidences of caesarean section,Reference Hoy, Venn, Halliday, Kovacs and Waalwyk 4 , Reference Huang, Song and Liao 6 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 induction of labourReference Hoy, Venn, Halliday, Kovacs and Waalwyk 4 , Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 and forceps delivery,Reference Hoy, Venn, Halliday, Kovacs and Waalwyk 4 , Reference Huang, Song and Liao 6 in their donor sperm-conceived cohort which may have potentially been associated with those low birth weight incidences. These reported obstetric intervention increases nonetheless did not adversely affect the continuous outcome measures of mean gestational age or mean birth weight.

The addition of these three studies has improved the meta-analysis of perinatal outcomes for donor-conceived neonates in comparison to those conceived spontaneously. This updated meta-analysis has shown an increase in the risk of donor sperm-conceived neonates being born of low birth weight and with an increased risk of being born with birth defects. This increased risk presents concerns for clinicians and patients when deciding to use a sperm donor. It also shows that previous notions that donor sperm-conceived neonates are no different to their spontaneously conceived peers may have been premature. Whether such altered risk is a result of increased incidences of preeclampsia in the donor sperm cohort,Reference González-Comadran, Urresta Avila and Saavedra Tascón 9 the use of sperm cryopreservation techniques inducing DNA damage,Reference Zribi, Feki Chakroun and El Euch 10 ovarian stimulation drugs,Reference Malchau, Loft and Henningsen 7 , Reference Poon and Lian 8 obstetric intervention or a combination thereof, is unclear.

Acknowledgements

D.A. is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.