Introduction

Electoral democracy is often referred to as democracy in which election-seeking politicians become more responsive to voters through electoral competition (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring and Lindberg2017). However, can the increasing levels of electoral democracyFootnote 1 have a negative effect on the politics of social policy-making? The extant literature in general demonstrates the positive effect of electoral democracy. For instance, it has been noted that democratization and intensified multiparty competition incentivize political elites to provide public goods to a wider range of the population, either to grasp or stay in power (De Mesquita et al. Reference De Mesquita, Smith, Morrow and Siverson2005). Moreover, even after the democratic transition, further increases in the level of electoral democracy push political elites to be even more pro-social welfare, including those who conventionally were less known for their social welfare offerings (Shim Reference Shim2019).

However, anecdotal evidence from a developed democracy in East Asia—Taiwan—points to the potential downside of electoral democracy progression for welfare politics. For instance, along with the intensification of electoral competition, numerous social welfare promises made by politicians before elections tend to be eventually abandoned or postponed. Even if kept, many social welfare programs face problems during the implementation stage as a result of politicians’ election-motivated rushed introduction of them. Examples include the lack of trained carers or care-facility infrastructure, budget shortages on the part of the local governments responsible for the provision of welfare services, or the ad hoc attempts to secure the necessary funding through luxury goods/gambling/alcohol/tobacco taxes (Shim Reference Shim2016).

Although the relationship between increasing levels of electoral democracy and short-sighted welfare politics can have broader implications for many aspiring or new democracies, it is nevertheless yet to be explicitly theorized and empirically tested. In this article, I argue that as the level of electoral democracy increases voters have more channels through which to make demands, and the media have more opportunities to reflect on what politicians do, while the latter find themselves under greater pressure to “act for” voters. The increase in electoral expense across advanced democracies is a telling manifestation of the state of fierce electoral competition (Clark Reference Clark2019). Faced with the growing electoral pressures, politicians are more likely to overpromise social welfare benefits to improve their electoral prospects. Drawing theoretical insights from legislative, electoral, and welfare studies, I posit that the overpromising of social welfare benefits is likely due to three cognitive biases on the voter side—recency bias, relatability/visibility bias, and promise-rewarding bias—allowing politicians to reap the benefits of increasing electoral chances without necessarily facing the negative consequences of under-delivery.

Using Taiwan as its case study, this article tests the key argument by investigating whether and to what degree the increasing level of electoral democracy affects politicians’ overpromising of social welfare benefits. Considering that overpromising refers to promising more than one can deliver, whether a policy is overpromised or not can only be revealed with hindsight based on its status vis-à-vis under-delivery. The most meaningful changes in social welfare benefits take the form of legislation; and, in relation to legislation, under-delivery mainly manifests itself at two different stages of the legislative process: i) politicians propose a social welfare bill but it fails to pass; ii) a social welfare bill is passed but fails to be implemented as intended, for example by experiencing significant delays or seeing reduction in benefit levels.Footnote 2 In this article, I focus on the first legislative stage to examine the evidence for politicians’ overpromising. Specifically, evidence in this article derives from quantitatively comparing the fates of sponsored social welfare bills and other bills.

Drawing from the post-democratic-transition period in Taiwan (1992–2016) the evidence demonstrates that, during election periods, politicians are more likely to propose social welfare legislation that is subsequently not passed. This tendency was magnified in tandem with rising levels of electoral democracy and particularly pronounced in legislative proposals put forward by election-sensitive legislative-branch members vis-à-vis relatively election-neutral executive-branch ones.

This article contributes to the comparative welfare state literature by adding much-needed nuance to the relationship between electoral democracy and welfare politics in numerous new democracies, whose political conditions differ from those of the established Anglo-European ones. That is, in new democracies where both left- and right-leaning parties face minimal ideological constraints to providing social welfare benefits (Peng and Wong Reference Peng, Wong and Pierson2010; Shim Reference Shim2020), the deepening of electoral democracy would have both positive and negative effects on welfare politics at the same time. On the positive side, increasing levels of electoral democracy and multiparty competition tend to shift elites’ key welfare beneficiary target from a few privileged individuals to the many (Shim Reference Shim2019). At the same time, on the negative side, the progression of electoral democracy can further myopic social welfare promises made during election periods.

Only after considering both positive and negative aspects of electoral democracy can we understand why developed East Asian democracies such as Taiwan have not consolidated their welfare states. Students of East Asian welfare states have often taken an optimistic view on the effect of democracy, in that the commencement of multiparty competition in the early 1990s was pivotal (Wong Reference Wong2006; Aspalter Reference Aspalter2002) in turning weak welfare systems into a set of programs based on social solidarity and universality, with redistributive implications (Peng and Wong Reference Peng, Wong and Pierson2010, 658). However, two decades after its democratic transition, Taiwan's social expenditure took up 10–11 percent of its GDP between 2012 and 2017 (Statistical Bureau of Taiwan 2018), far short of the OECD average of 21–22 percent for the equivalent period (OECD 2018).

By theorizing and testing the political logic behind “overpromising social welfare benefits,” this article helps us to understand an important elite-level factor preventing developed and consolidated East Asian democracies from expanding or modernizing their welfare state. Having a systematic understanding on a key sabotaging factor is crucial because, if the current trend persists, Taiwan is highly likely to eventually find itself stuck with a mediocre level of welfare state development. The lack of welfare-state consolidation is particularly concerning in light of the sociodemographic crisis the country is going through. For instance, data from The Executive Yuan's Accounting and Statistics Department in Taiwan show that by 2012, the country's fertility rate hit 1.2 while life expectancy soared to nearly 80. Extrapolating from the current trend, the US Census Bureau report (He, Goodkind, and Kowal Reference He, Goodkind and Kowal2016) shows that Taiwan will be the world's fourth oldest country by population in 2050.

Beyond its implications for the prospect of welfare state consolidation, demonstrating the state of overpromising and clarifying the pertinent political logic offer valuable insights into why the advancement of electoral democracy goes hand-in-hand with decreasing political trust in representative political institutions. According to the Asian Barometer survey (2013), when respondents were asked whether they have some or a great deal of trust in various institutions in Taiwan, people placed the lowest levels of trust in two legislative branch-related political institutions: political parties (14 percent) and parliament (19 percent). The result contrasts with the amount of trust people put in political institutions in the executive branch, e.g. top political office (34 percent), national government (33 percent), local government (50 percent), and civil service (48 percent). What is particularly worrying is that the level of trust on two legislative-branch institutions went down vis-à-vis previous periods in Taiwan and are considerably lower—30–60 percent—compared to other less or non-democratic countries in East Asia such as Indonesia, Thailand, or Malaysia. Trust in institutions can be increased if the norms of promise-keeping is fulfilled (Warren Reference Warren1999). In view of this, findings from the surveys clearly echo the key patterns observed in this article—overpromising is clearly linked to election-seeking legislative branch members and tends to intensify along with the progress of electoral democracy.

The article is organized as follows: I begin by discussing the relationship between election-induced shortsightedness, voter biases, and welfare politics. Second, I introduce the contexts behind welfare politics in Taiwan, explain the bill sponsorship data, and define social welfare issues. Third, regression analyses are employed to examine how and to what extent political elites overpromise social welfare benefits during election times. In the fourth and concluding section, I summarize key findings and their generalizability, and identify avenues of future research.

Election-induced shortsightedness and welfare politics

It is widely known that democratic transition is more likely to lead to the provision of social welfare (Lindert Reference Lindert2004; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014). Beyond the established democracies, this relationship has been borne out by a wealth of empirical works demonstrating the positive effect of democratization on welfare expansion in East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009). One of the key explanations for this phenomenon can be found in the change in elite-level incentives following the democratic transition. First, elections clearly serve as a device for disciplining self-interested politicians who want to extract rents from their position (Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn1986). Moreover, electoral competition tends to push political elites to provide social welfare to a wider range of population beyond just their small circle of core supporters (De Mesquita et al. Reference De Mesquita, Smith, Morrow and Siverson2005). Added to this, the latest evidence based on the continuous understanding of electoral democracy level demonstrates that, even after a country's democratic transition has occurred, political elites tend to prioritize social welfare more in tandem with the deepening of democracy and growing electoral competition (Shim Reference Shim2019).

Although politicians in general are more likely to prioritize a social welfare agenda in the context of an increasing level of electoral democracy, whether the prioritized initiatives can be successfully made into law and implemented to bring the intended policy benefits to the public is another question. As will be detailed later, examples of election-time social welfare overpromising in Taiwan make clear that prioritizing and delivering are two different things. Then one might wonder how politicians can get away (or believe they can get away) with under-delivering social welfare promises without being punished by voters. Here I attempt to explain this by building on theoretical insights from legislative, electoral, and welfare studies.

It has been noted that while elections can offer a mechanism of accountability, they can also introduce a bias towards short termism at the same time (Nordhaus Reference Nordhaus1975; Eslava Reference Eslava2011). Through elections, admittedly, voters are offered a chance to select the most competent, hard-working, and high-achieving politicians. However, because these qualities are hard to evaluate accurately—particularly on a regular basis—politicians running for office have implicit incentives to maximize voters’ perception of their positive qualities (Persson and Tabellini Reference Persson and Tabellini2002; Alesina and Tabellini Reference Alesina and Tabellini2008). This is especially so if politicians prioritize election-seeking goals. In order to understand how politicians maximize voters’ perception to their advantage, the following three cognitive biases on the voters’ side need to be considered:

First, recency bias: In the ideal representative democracy, politicians should be evaluated based on their achievements throughout their whole elected term. However, established research in behavior psychology demonstrates that people in general tend to value recent experience more in making an overall judgement (Kahneman Reference Kahneman and Daniel2000). Within the political context, evidence shows that voters reward or punish incumbents for their policy records particularly closer to the next election—more than for other time periods (Nordhaus Reference Nordhaus1975). The recency bias in politics occurs because of voters’ waning ability to recall past events and/or their tendency to view the most recent event as a good proxy for politicians’ future actions (Mackuen, Erikson, and Stimson Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992; Healy and Lenz Reference Healy and Lenz2014). Reflecting this voter bias, models of political business cycles have repeatedly shown that incumbents want to perform better before elections so as to appear talented (Shi and Svensson Reference Shi and Svensson2006). Specifically, when it comes to public policies, it is widely reported that incumbents tend to implement popular policies at the end of their term in office and unpopular ones at the beginning thereof (Mackuen, Erikson, and Stimson Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992; Healy and Lenz Reference Healy and Lenz2014).

Second, visibility/relatability bias. Let us assume that, for the same amount of time and effort, politicians can choose to prioritize either a visible/simple/short-term public policy or an invisible/complex/long-term one. Even though the latter type can increase voters’ welfare in the long term to a greater extent, due to the easy relatability to potential benefits, voters are more likely to reelect an incumbent politician who prioritizes the former type over the latter (Garri Reference Garri2010). This renders policy short-termism a natural equilibrium for election-seeking politicians (ibid.). And empirical evidence supports the notion that politicians are likely to focus on easily observable measures of competency, such as promising more or spending more. Linking politicians’ career-driven political myopia to election-induced budget deficits is a clear illustration of this (Persson and Tabellini Reference Persson and Tabellini2002; Alesina and Tabellini Reference Alesina and Tabellini2008).

Among the many potential initiatives politicians can take, social welfare benefits are a natural candidate. Research clearly demonstrates that a majority of voters favor generous social welfare policies (Pierson Reference Pierson1996; Brooks and Manza Reference Brooks and Manza2006) many of which are highly relatable to both the middle class—such as childcare, parental leave, long-term care, healthcare—as well as to those who are less privileged—for example unemployment benefits and income transfer. Coupled with this high public demand, the high visibility of social welfare benefits in general and universal ones in particular (Gingrich Reference Gingrich2014) makes offering them an attractive election tool for politicians preparing for the vote. Latest findings showing that the government's expansion or cutback of two key welfare state programs—pensions and unemployment protection—are directly linked to the popularity rate (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Jensen, Arndt and Wenzelburger2017) lend further credence to the electoral utility of highly visible/relatable social welfare benefits.

Third, bias can also be found among voters having positive perceptions not only of politicians who actually deliver on their promises but also of those who simply make promises in the first place. In the legislative studies literature, it has been long noted that, in addition to “credit-claiming” based on actual delivery of policies, “position-taking” through promising itself can have electoral reward (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974); even if politicians are not ultimately successful in achieving the outcome desired by voters, promising policies preferred by voters nevertheless shows a politician's standing with them and signals shared values. For this reason, both delivering and promising policies for the represented are known as “acting for” representation, often known as “substantive representation” (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). However, from politicians’ point of view, it is much less costly to promise than to actually deliver policies. Therefore, election-oriented politicians are more likely to commit to promising more.

Given these three voter biases, I argue that politicians have incentives to prioritize social welfare issues over others (because they are more visible and relatable than other issues) during election times (because voters weigh what happens before the election more than other times). And it is likely that the form prioritization will take is that of overpromising (because promising itself tends to be positively recognized by voters yet requires less effort than delivering). All considered, voter cognitive biases will allow politicians to make social welfare promises during election times without facing the negative consequences of under-delivery. Therefore, we can derive the following theoretical expectation:

H1a: Social welfare benefits will be overpromised during election periods compared to during nonelection periods.

The importance of elections does not stay the same after a country's democratic transition. Relatedly, research shows that, even after democratic transition, the specific level of electoral democracy affects the politics of social policy-making (Shim Reference Shim2019). In light of this, we can expect that the deepening of electoral democracy can also have an impact on politicians’ inclination to overpromise social welfare policies. Specifically, I expect the overpromising tendency will grow larger. From this perspective, the related hypothesis can be formulated as follows:

H1b: Effects of H1a (social welfare benefits being overpromised during election periods) will be particularly pronounced as the level of electoral democracy increases.

The pressure for election-time overpromising is not felt to the same degree between different government branches. Within the government, legislative-branch members are not the only actor capable of making policy proposals. Beyond implementing policies, executive-branch members are also known as a policy proposer (Alesina and Tabellini Reference Alesina and Tabellini2007); in many countries, they can even propose policies in the form of executive-branch bills. Considering that many top positions in the executive branch are political in nature, such as cabinet minister or president, executive-branch members can also be thought of as incentivized to overpromise social welfare policies during election times. Still, a large proportion of executive-branch members in developed democracies tend to be nonelected career bureaucrats hired on merit and enjoying career stability. For this reason, executive-branch members are often preferred in policymaking if political short-termism is prevalent (Alesina and Tabellini Reference Alesina and Tabellini2008); there is a solid body of literature from both new and old democracies demonstrating how professional bureaucracies lengthen the time horizons of policymaking (Rauch Reference Rauch1995; Rauch and Evans Reference Rauch and Evans2000). On the contrary, almost all the members of the legislative branch in developed democracies need to meet with the approval of voters during election times. In view of this, the following expectation can be derived:

H2: Compared to executive-branch members, effects of H1a (social welfare benefits being overpromised during election periods) will be particularly pronounced by legislative-branch ones.

Case selection and welfare politics context in Taiwan

Case selection: Taiwan

Taiwan is chosen as the case study to test the three aforementioned hypotheses; the following conditions make this case a particularly ideal one.

First, public demand (as measured by various surveys) for more state-based welfare has been high in the past decades. For instance, the General Attitude Survey of Social Attitudes conducted by Academia Sinica in 1991—a nation-wide survey conducted on a total of 1,590 people—showed that 44 percent of respondents found state welfare unsatisfactory, while 70 percent thought welfare expenditure should be increased in the future (Ku Reference Ku1997). Moreover, when a 2009 telephone survey in Taiwan asked over 1,100 people questions about the government's role in social welfare, roughly 90 percent of respondents wanted a greater role for the state in i) implementing progressive taxation or ii) improving living standards of low-income people (Wang, Wong, and Tang Reference Wang, Wong and Tang2013). In addition, when the media saliency of welfare and non-welfare issues are compared in Taiwan, the former was 25 percent more visible compared to the latter.Footnote 3 All in all, both survey and media evidence point to the relatability and visibility of social welfare issues in Taiwan.

Second, electoral security is not guaranteed for a large proportion of politicians. For instance, after the introduction of single member districts in 2005, approximately 60 percent of victors won their seats by receiving less than 55 percent of the vote.Footnote 4 Moreover, that Taiwan has a substantial proportion of swing voters—30–40 percent—and that their choice is often decisive in electoral outcome (Wong Reference Wong2013) together aggravate politicians’ electoral insecurity. Combined with the high voter demand for social welfare, politicians’ uncertain electoral prospects constitute a favorable condition to test H1a.

Third, Taiwan's electoral-democracy level has improved significantly even after democratic transition, a necessary condition for testing the continuous effect of the deepening of electoral democracy (H1b). Namely, the first direct democratic election was held in 1992 (a general election)—which can thus be marked down as the moment of Taiwan's democratic transition. Moreover, the island nation consolidated its democracy in 2008 which marks the year of passing Huntington's two turn-over test (Reference Huntington1991).Footnote 5 The deepening of electoral democracy after 1992 is clearly reflected in Taiwan's electoral democracy scoreFootnote 6—moving from the lowest point 0.31 to the highest point 0.81. At the same time, the fact that the rising level was not linear (for instance, there was a big increase from 0.35 to 0.67 between 1996 and 1997 as well as several years when the score decreased such as 2001–2005, 2009–2012, or 2013–2014) indicates that the deepening process involved more than the simple passage of time since the democratic transition.

Fourth, both the executive and legislative branches in Taiwan were allowed to make policy proposals in the form of sponsoring legislation during the period of observation (this is not the norm in every country; for instance, legislation cannot be sponsored by the executive branch in the United States). This enables us to compare the election-time overpromising of social welfare benefits across the two government branches, with them clearly experiencing different levels of electoral pressure. Moreover, executive-branch members in Taiwan are professional bureaucrats scoring very high on the “Weberian Scale”—measured as the degree to which bureaucrats are employed through meritocratic recruitment and get offered predictable, rewarding long-term careers (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999). Therefore, this domain serves as a clear reference point for a more election-sensitive legislative branch—which is the key concern of H2.

Fifth, there is a lack of ideological constraints for both left- and right-leaning politicians in providing social welfare benefits. The fact that national identity/self-determination vis-à-vis mainland China forms the primary political cleavage in Taiwan (Hsieh and Niou Reference Hsieh and Niou1996), while social welfare issues are no more than a secondary political dimension, has significant implications for understanding the pre-election behavior of both left- and right-leaning party politicians. The extant research points out that parties tend to be more strategic on their non-primary-issue dimensions, demonstrating behavior ranging from catch-all to leapfrogging between issues (Alonso Reference Alonso2012). Echoing this, in Taiwan the right-leaning Chinese Nationalist Party has clearly demonstrated highly strategic behavior on the expansion of social welfare benefits (Peng and Wong Reference Peng, Wong and Pierson2010). Further, as will be detailed below, the Chinese Nationalist Party's opportunistic approach to social welfare issues is also visible in the retrenchment of existing welfare benefits. This condition sets Taiwan apart from numerous Anglo-European democracies, where social welfare issues tend to be the primary dividing line between the major left- and right-leaning parties; for instance, constrained by ideology, right-leaning politicians would not be able to freely engage in social welfare-expansion bidding-up. Moreover, research also shows a government facing a strong anti-welfare opposition ought to address the fiscal risks of expansionist social welfare to minimize electoral damage (Green-Pedersen Reference Green-Pedersen2002).

Welfare politics in Taiwan

In addition to possessing key conditions to test three hypotheses concerning overpromising of welfare politics, examples indicate that Taiwan indeed has experienced heated political competition over social welfare issues since its democratic transition. The welfare politics features overpromising and involve both executive and legislative branch members.

While Taiwan was governed by martial law until 1987, beneficiaries of social welfare schemes were confined to a few privileged clienteles supporting the authoritarian regime—such as the military or government bureaucrats (Aspalter Reference Aspalter2002). Beyond these core supporters, the government-provided welfare benefits were largely limited to the productive sectors of society—such as state-owned enterprises or large firms’ employees, thereby excluding the weak and marginalized like the elderly, unemployed, self-employed and farmers (Ku Reference Ku1997); this clearly echoed the “developmental welfare state” thesis whereby the government subjugates social policies to the goal of economic ones (Holliday and Wilding Reference Holliday and Wilding2003).

However, since the beginning of a direct general election in 1992, electoral competition utilizing social welfare benefits came to the surface. Namely, the left-leaning Democratic Progressive Party (henceforth DPP) attempted to broaden its issue base beyond the Taiwanese independence/national-identity policy domain while the right-leaning Chinese Nationalist Party (henceforth KMT) tried to develop a new base of electoral support beyond its developmental-state-period clienteles (Wong Reference Wong, Fell and Hsin-Huang2019; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013). Clear manifestations of heated welfare politics in the 1990s were the introduction of the national health insurance by the KMT (which snatched the original initiative from the DPP) and various election promises offered by both parties on old-age benefits such as pension or income subsidies (Fell Reference Fell, Fell and Hsin-Huang2019)

Continuing the momentum created in the previous decade, the fierce welfare politics pattern persisted after the turn of the millennium. Particularly well-known are welfare pledges made by left- and right-leaning candidates before presidential elections—many of which turned out to be examples of overpromising.

For instance, in preparation for the 2000 presidential election, the DPP candidate Chen Shui-bian came up with several social welfare packages designed to attract general voters. The signature plan was a catchy family-welfare benefit called the “3–3-3 Plan” (the policy was designed to hand out NT$ 3,000 a month to the elderly, to subsidize mortgages at a 3 percent interest rate for first-time home buyers and entailed the government sponsoring health care for children below the age of three). Chen Shui-bian eventually won the Taiwanese presidential election in 2000, but when Chen came to power he announced that social welfare can be delayed while the economic development cannot (Wong Reference Wong2006). As a result, the party's signature 3–3-3 Plan had to be postponed (Yu Reference Yu2002). The mood then was well captured by a Taipei Times headline that read, “The DPP is sacrificing welfare for the economy” (Chiu Reference Chiu2001).

Overpromising of social welfare was not confined to left-leaning presidential candidates. A case in point is presidential hopeful Ma Ying-jeou before the 2008 presidential race. The KMT presidential candidate Ma Ying-jeou made a number of election promises on enhancing women's welfare—such as filling at least one-quarter of all cabinet positions with women, relaxing employment requirements for immigrant spouses, improving sports and leisure facilities for women, and creating at least 100,000 new jobs for women. However, when Ma came to power after the presidential election of 2008, the postelection under-delivery pattern recurred. For instance, DPP legislator Huang Sue-ying noted in 2010 that Ma failed to fulfill half of his electoral promises concerning women—such as appointing a cabinet one-quarter female or creating 100,000 new jobs for women (Loa Reference Loa2010)

Due to the presidential race's high saliency, pertinent welfare promises made by key presidential candidates tend to be well documented by academics and practitioners alike. However, it is less known that the legislative branch increasingly came to the forefront of welfare politics scene along with the deepening of Taiwan's electoral democracy. Like the South Korean case (Shim Reference Shim2019), as a presidential democracy, the legislative branch in Taiwan substantially increased its autonomy from the executive branchFootnote 7 and has been an aggressive political actor utilizing social welfare promises for its electoral goals. The tendency of the legislative branch to go further than the executive branch is seen at both party and individual-legislator levels.

As for the party level, for instance, a month before the 2012 presidential election, the KMT introduced a wide range of welfare subsidies targeting various social groups. Specifically, although the executive branch originally proposed NT$ 316 as the monthly subsidy for elderly farmers, the KMT raised it to NT$ 1,000 along with eight other kinds of welfare allowances—which included support for marginalized groups like children and youth, physically or mentally handicapped people, or aborigines. In the same month, much as had happened four years previously, the monthly pension for farmers saw an increase from NT$ 6,000 to NT$ 7,000—being backed by the KMT majority in the legislature.

When it comes to the individual-legislator level, “everyone for themselves”-type social welfare overpromising competition was not uncommon in Taiwan. A case in point is political competition over the level of the monthly pension for elderly farmers and fishermen prior to the 2008 election. Initiated by the Ministry of Welfare, Hygiene and Environment, an increase in the monthly pension for elderly farmers and fishermen from NT$ 4,000 to NT$ 5,000 was passed in December 2005. This was estimated to benefit 710,000 farmers and fishermen, and cost NT$ 23 billion per year (Ko Reference Ko2005). Both the DPP and KMT went a step further and increased this pension from NT$ 5,000 to NT$ 6,000 after holding an extra legislative session in June 2007; and, in the process of increasing NT$ 1,000, 16 relevant bills were proposed by legislators and the political escalation reached the point of eventually raising the promise level on the monthly pension for elderly farmers and fishermen from NT$ 5,000 to NT$ 15,000. Clearly the primary motivation behind this sudden benefit bidding-up process between legislators can be found from their intention to leave good impressions for voters.

Data and definition of social welfare

The article here taps into the whole universe of sponsored bills in TaiwanFootnote 8 (18,644 in total) put forward from the first general election in 1992 until the general election of 2016,Footnote 9 to examine politicians’ overpromising of social welfare during election times. First and foremost, bill sponsorship data is used because legislation has brought about the most substantial changes for electors on social welfare over the past decades in Taiwan—for instance, increased parental leave, extending unemployment insurance coverage, or universal health care insurance. Moreover, sponsorship data provide a rich source of information on legislators’ preferences and priorities.Footnote 10 For instance, sponsoring a bill is an opportunity to express support for a certain issue through which a legislator can send signals to median voters (Kessler and Krehbiel Reference Kessler and Krehbiel1996). Although the amount of effort a legislator puts into sponsoring or cosponsoring a bill can vary, in Taiwan legislators are selective about which bills to sponsor (Shim Reference Shim2021) and take the task seriously since bill-sponsorship history is public record and, in turn, a source of praise or criticism by performance-evaluating nongovernmental organizations like Citizen Congress Watch. For this reason, the extant literature notes that legislative support on key policy issues can be an effective means of achieving electoral goals, as it can serve as clear evidence of the accomplished performance of duties—demonstrating one's credentials, commitment, and achievement (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). Reflecting this, the advantage of examining legislative changes (compared to other measures such as welfare-expenditure change) in explaining welfare politics has already been well noted by students of comparative welfare states (e.g., Wenzelburger et al. Reference Wenzelburger, Jensen, Lee and Arndt2019). Finally, unlike other datasets such as roll call votes or legislative surveys, bill sponsorship datasets exist continuously during the period of observation in Taiwan; and because the sponsoring time is recorded with the unit of day, it is ideal to estimate the effect of election periods.

Based on the details specified in the constitution, as mentioned earlier, Taiwan allows bills to be submitted by both the legislative and executive branch, which helps us to distinguish preferences between the two branches. The legislative branch bills are predominantly composed of legislator-proposed bills;Footnote 11 to propose a bill, each legislator has needed the support of 15 or more members of the Legislative Yuan before 2008, and 33 or more members since 2008.Footnote 12 In light of this sponsorship data, every bill is coded as either “welfare or not” and the following three major areas of social welfare issues are coded as “welfare”Footnote 13 based on the bill's title and key summaries in official government documents. Such coding makes both the welfare and non-welfare categories mutually exclusive and totally exhaustive (see Appendix A for the specific coding rules and frequently appearing welfare keywords in Taiwan).

Social security: health insurance, pension, accident/work injury insurance, employment insurance, long-term care insurance

Public assistance: income maintenance, emergency aid, national compensation, support for the disabled, support for refugees and immigrants, minimum income

Social services: childcare, elderly care, juvenile care, mother/women care, medical protection and social protection, housing, education, labor welfare

By this definition, roughly 24 percent of all sponsored bills during the period of observation—4,489 out of 18,644—are classified as “welfare” and, as is clear from Figure 1, there had been an increasing prioritization of welfare issues moving from the second to eighth legislative sessions. Moreover, reflecting active legislative activities in general and their focus on welfare issues in particular, 78.5 percent of all sponsored bills derive from legislative branch members (14,642 out of 18,644) and welfare issues make up 26.4 percent. By contrast, executive branch members sponsored 21.5 percent of all sponsored bills (3,865 out of 18,644), of which welfare issues make up 15.6 percent.

Figure 1. Proportion of social welfare bill sponsorship (from all submitted bills) by legislative session.

Quantitative evidence: regression analysis

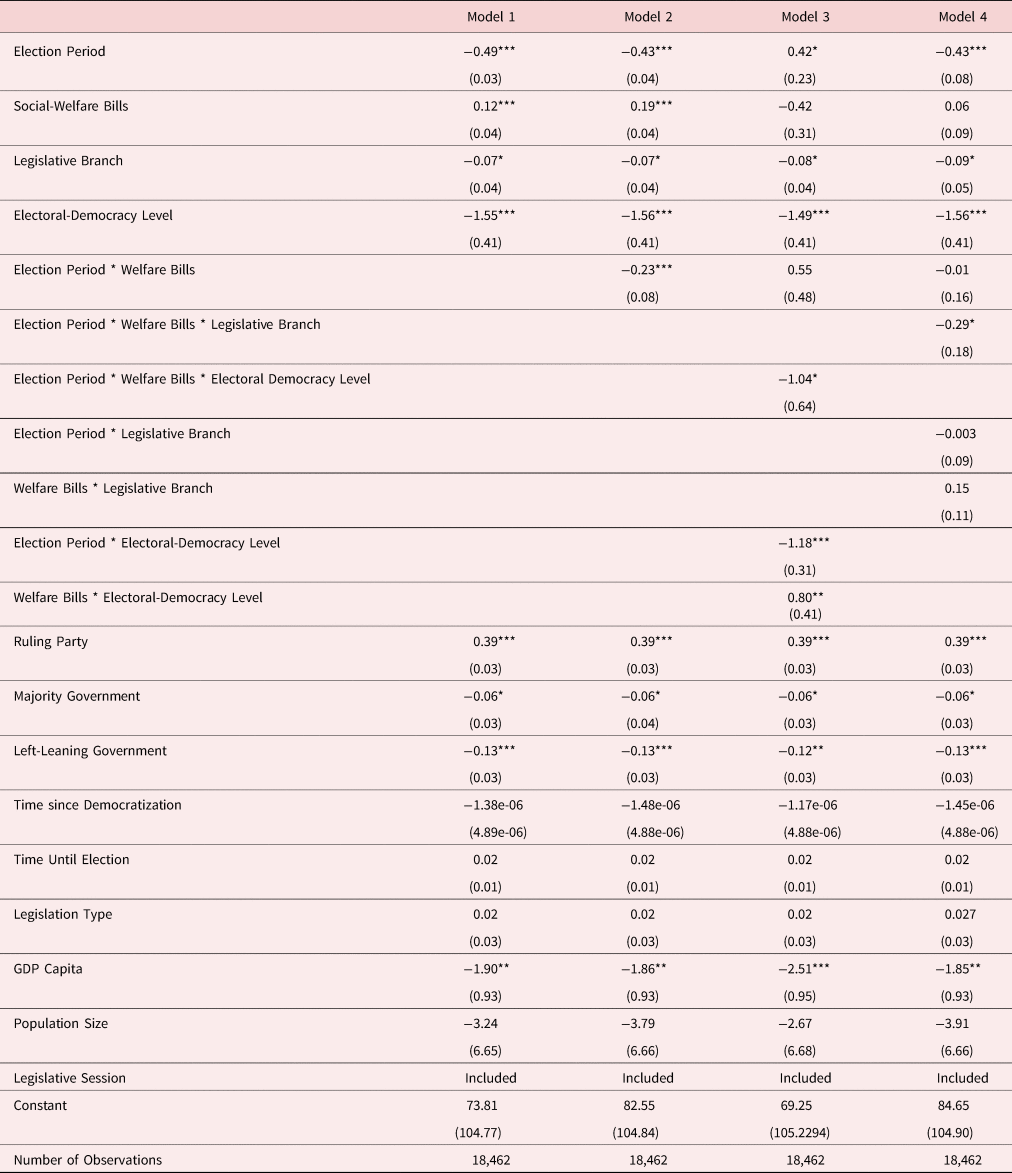

To test the hypotheses while also taking other confounders into account, I carried out logistic regressions for sponsored bills during the period of observation in Taiwan. The outcome variable is whether a submitted bill is successful or not (failure 0, success 1) for all four models. Here, “failure” is defined as the inability of the bill initiator to pass one's proposed bill. The form that “passing” can take is either the amending of an existing law or the enacting of a new one. There are in total four explanatory variables employed in regressions to test politicians’ overpromising of social welfare benefits: election period, social welfare bill, legislative-branch sponsor, and electoral-democracy level. Model 1 is the base model, with four explanatory variables but without any interaction term directly testing any of the three hypotheses. Model 2 directly tests H1, with the interaction effect between two explanatory variables: election period (nonelection period 0, election period 1)Footnote 14 and social welfare bill (non-social welfare 0, social welfare 1). If H1a is correct, then I expect to observe higher chances of social welfare bill failure proposed during election periods than non-election periods. To test H1b and H2, an interaction term of the level of electoral democracy (continuously ranging from 0 to 1, measurement based on the aforementioned Varieties of Democracy dataset) and the legislative-branch sponsor (executive-branch sponsor 0, legislative-branch sponsor 1) are added to H1a in Models 3 and 4 respectively, making each a triple-interaction model. Since a three-way interaction means that the interaction among the two factors varies across the levels of the third factor, I expect that the interaction effect of H1a (between election period and social welfare) will be different depending on the electoral democracy levels (H1b) as well as the submission entity (H2). Specifically, if H1b and H2 are in line with my expectations, I expect to observe higher degrees of election-time social welfare legislative failure when the level of electoral democracy is high (compared to lower ones) or when the submission entity is a legislative branch member (compared to executive branch members). Following the convention, all constituent parts of triple interaction terms are included in Models 3 and 4.

Other control variables that can potentially affect the success rate of bills in general and social welfare bills in particular draw from legislative and welfare studies (e.g. Ellickson and Whistler Reference Ellickson and Whistler2000; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2009): i) GDP per capita (continuous, logged); ii) population size (continuous, logged)Footnote 15; iii) legislative initiative type (enactment 0, amendment 1); iv) known ideological spectrum of bill initiator at the time of bill submission (right-leaning 0, left-leaning 1)Footnote 16; v) ruling party status (opposition party 0, ruling party 1Footnote 17); vi) majority government period (minority government 0, majority government 1); vii) the time gap between the first general election in 1992 and the bill sponsorship day (continuous); viii) the time gap between the bill sponsorship day and the next general election day (continuous, logged); and ix) legislative session dummy.

To give a brief rationale behind controlling each variable, GDP per capita and population size are included as macro-level variables affecting supply and demand of social welfare bills respectively. Legislative initiative type is included since enacting a bill—making a bill from scratch—is, in general, substantially more time consuming and politically tricky than amending a bill. The bill initiator's known ideological orientation is included to examine the conventional expectation that being a left-leaning political actor would mean making more effort to ensure a submitted social welfare bill is successful. Whether the bill submitter enjoys ruling-party status or whether the bill is submitted during periods of majority government is included, with the expectation that passing a bill as an opposition party member or during a period of minority government will be more challenging. The passage of time since the first general election—the democratic transition—is included with the concern that the rising level of electoral democracy might be simply the function of linear progression in time. The time-lag between the bill sponsorship day and the next election is controlled because bills sponsored closer to election day imply less time for legislative deliberation in Taiwan's context. In Taiwan, all sponsored bills that remain unpassed automatically die when a legislative session terminates; since an election day tends to be only a month away from the end of a legislative session, submitting a bill closer to election day corresponds to less time.Footnote 18 Finally, a legislative session dummyFootnote 19 is included to account for the effect of session-specific events as well as general changes in the quality and quantity of sponsored bills over time. The logistic-regression results are based on robust standard errors and are reported in parentheses.

To begin with, Model 1 is the base model and shows the effect of four explanatory variables without any interaction term. It shows that the election period, deepening of electoral democracy, and a legislative-branch sponsor causes a drop in the success rate of proposed bills; contrariwise, being a social welfare bill leads to a higher chance of passing than if a non-social welfare bill. To test H1a, which expects that politicians’ overpromising of social welfare bills will be pronounced during election periods vis-à-vis during nonelection period, Model 2 adds an interaction effect between election period and bill type. The results in Table 1 show the negative effect to be highly statistically significant. Related to this, Figure 2 visualizes the change in success rate of social welfare and non-social welfare bills by electoral cycle.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of election period on social welfare overpromising.

Table 1. Logistic Regression Results Predicting Social Welfare Overpromising.

Notes: (1) ***p <0.01, **p <0.05, *p<0.1.

As is clear, both social welfare and non-social welfare bills see a decrease in their success rate during election periods compared to nonelection ones. However, the degree to which this happens differs clearly between the two bill types: from 36.7 percent to 27.9 percent for non-social welfare bills and from 40.8 percent to 27 percent for social welfare ones. These results clearly support H1a.

Moving on, Model 3 tests H1b, which predicts that the effect of H1a (overpromising of social welfare during election periods) is positively related to the deepening of electoral democracy. To verify this claim, a triple-interaction term is used with three pertinent explanatory variables: election period, bill type, and electoral democracy level. The statically significant negative effect identified in Table 1 supports H1b. Specifically, as is clear from Figure 3 (left), rising levels of electoral democracy reduce the success rate for both social welfare and non-social welfare bills; this effect is also made clear from the negative, and highly statistically significant, interaction term between election period and electoral-democracy level presented in Model 3.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of electoral-democracy level (left) and sponsorship entity (right) on social welfare overpromising.

However, if we distinguish between election and nonelection period the degrees to which the respective success rates drop vary substantially. That is, for the nonelection period—moving from the lowest to the highest level of electoral democracy in Taiwan during the period of observation—the success rate drops far less for social welfare bills compared to for non-social welfare ones: some 51.6 percent to 34.6 percent for the latter versus 47.4 percent to 39.3 percent for the former. However during election periods, for the equivalent changes in the electoral-democracy level, the success rate drops more or less to the same extent for both bill types: namely 53.2 percent to 24.4 percent for non-social welfare bills versus 54.6 percent to 23.3 percent for social welfare ones. Based on the widening success-rate gap between electoral and non-electoral periods, it can be concluded that the negative effect of progressing electoral democracy is particularly pronounced for social welfare bills during election periods.

Finally, Model 4 tests H2 with a triple-interaction term between electoral cycle, bill type, and sponsorship entity. The expectation is that we are more likely to observe the effect of H1a (the overpromising of social welfare benefits during election periods) from legislative-branch members compared to from executive-branch ones. Confirming H2, the triple-interaction term is negative and statistically significant; the effect of legislative-branch members’ sponsoring of welfare bills is illustrated in Figure 3 (right). Compared to the nonelection period, the success odds for the election period drop for all bills submitted by both executive- and legislative-branch members. However, insofar as social welfare bills are concerned, the degree of drop is roughly 1.5 times higher for bills submitted by legislative-branch members as compared to ones submitted by executive-branch members: a 15 percent (from 41.1 percent to 26 percent) and 9.2 percent (from 39.7 percent to 30.3 percent) fall respectively.

To provide a more vivid sense of how legislative-branch members prioritize social welfare legislation, Table 2 summarizes the state of highly salient and largely popular social welfare-bill types with the same (or largely similar) legal titles, as submitted at different points in time over the course of ten-year intervals after Taiwan's democratic transition.

Table 2. Legislation Overlaps of Popular Welfare Bills over Time.

First, the primary political actor contributing to these highly popular social welfare change proposals has been the legislative branch members, making up 98 percent of the total submitted bills—387 out of 396 bills (the numbers in parentheses indicate the specific bill numbers submitted by the legislative branch members). Second, the number of the same popular welfare bill type submitted at specific times has clearly increased over time. For instance, labor insurance bills with the same or largely similar legal titles have been submitted, on average, six by legislative branch members between 1994 and 1995. This average moved upward to 20 a decade later, and then to 46 two decades later. Third, upon careful reading of the contents of each bill, legislative-branch-submitted bills tend to be shorter and, more importantly, more political and non-technical than executive-branch submitted ones. To give an example, 44 out of the 46 employment insurance bills submitted were by legislative branch members between 2014 and 2015; the key changes were about: i) increasing the maternity subsidy for mothers having multiple births; ii) lowering the number of job-seeking pieces of evidence required to apply for unemployment assistance from two to one; iii) granting maternity leave and subsidies for people fostering children under the age of three; iv) including women and low-income families in the employment subsidy support scheme; v) including women who had suffered domestic violence in the employment assistance support scheme; and, vi) forbidding employers from discriminating against a job-seeker based on the person's record related to military service or having an incurable disease. These proposed changes clearly echo politicians’ tendency to take advantage of one of the three aforementioned cognitive biases on the voter side—the latter tend to appreciate visible or relatable benefits.

For the sake of the robustness of the findings I have presented so far, I removed each social welfare category described in the definition part to examine whether anything changes (not presented here to preserve space); this did not alter any of the key findings presented here. Moreover, there can be difference in the direction and significance of each welfare bill between election and non-election periods; for instance, social welfare bills sponsored during non-election periods can be about rolling back social welfare benefits or expanding insignificant ones just for the signaling purposes. If this is the case, the quantitative drop in the success rate of submitted social welfare bills during election times can be compensated for the qualitative increase in the bill contents. To address this concern, I randomly sampled 250 social welfare billsFootnote 20 from non-election and election period and coded the significance (significant or not) and direction (expansion or not) of welfare bills (see Appendix B for the details). The results indicate no systematic difference between the two periods showing roughly 85 percent of social welfare bill submitted at any period falling into “expansion” category and 95 percent into “significant” category. Finally, since Taiwan has had a mixed-member electoral rule for the period of observation, I ran a separate regression between district-tier legislators and party-tier legislators to examine whether the logic of overpromising can be found in both tiers. The result shows that the overpromising logic applies to both tiers.

Further discussion: short-sighted welfare politics in welfare retrenchment

This article has focused on the welfare expansion aspect of politics in Taiwan. However, we should not neglect the fact that, in certain social policy areas, Taiwan is experiencing the politics of welfare retrenchment. The year 2012 marks an important turning point for Taiwan's welfare politics in the sense that, after the presidential and general elections in January, the “new” politics of welfare retrenchment (Pierson Reference Pierson1996) became highly visible alongside the existing “old” politics of welfare expansion. In other words, politicians’ virtue-signaling attempts now not only included providing the social welfare that the public desired but also preventing already-existing benefits from being taken away—which clearly resembles the “new” politics of social welfare that began to appear in developed Western welfare states three decades ago (Pierson Reference Pierson1996).

For instance, with the beginning of a new legislative session in 2012, the reelected president Ma showed his support for rationalizing Taiwan's pension system—whose financial sustainability was increasingly becoming perceived as a major national crisis by the public according to the Taiwan Indicator Survey Research (Taipei Times 2013). He emphasized that “if we do not embark upon the pension reform today, we will regret it tomorrow” (Wang Reference Wang2015) and set up a pension reform task force. From the electoral viewpoint noted in the welfare state literature (Mackuen et al. Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992; Healy and Lenz Reference Healy and Lenz2014), the timing of Ma's retrenchment initiative made it a politically rational move because it was the beginning of his second and last term as president. One of the first pension-reform attempts made by the executive branch was to propose a bill reducing the number of government retirees receiving year-end pension bonuses from 423,000 to 42,000 people; although it was supported by the opposition DPP, KMT legislators voted it down in November 2012. Another major pension-reform effort was put forward by the opposition party DPP in 2015, in the form of a legislative proposal; at the center of the bill lay removing the 18 percent preferential interest rate on savings provided to military personnel, civil servants, and public school teachers who had begun their careers prior to 1995.Footnote 21 However, the proposal was blocked by KMT members in the legislature.

Although four years is rather short to extract any generalizable patterns, what is relatively clear from the politics of retrenchment in Taiwan is the difference between the government's legislative and executive branches. That is, in general, relatively election-neutral executive-branch members tend to propose welfare-retrenchment plans only to be turned down by election-sensitive legislative-branch members. This tension was visible when the frustrated president Ma blamed the legislature for blocking his pension reform during his second term, at which time his party KMT held a legislative majority. The opportunistic political dynamics germane to the politics of retrenchment are essential to understanding why Taiwan's key social welfare schemes suffer from fiscal ill-health. As is often said, the name of the game for welfare expansion is “credit-claiming,” while it is “blame-avoidance” for welfare retrenchment (Pierson Reference Pierson1996). In Taiwan, if the former stage is characterized by overpromising of social welfare benefits, the latter stage features a lack of the necessary steps to make particular social benefits fiscally sustainable, e.g. increasing premium, raising tax, or curtailing benefits.

Needless to say, political inaction is bound to harm Taiwan's welfare state. According to the National Audit Office, Taiwan's numerous welfare funds are expected to go bankrupt in the coming decades if the current trends continue: labor insurance in 2027, civil servant insurance in 2030, the national pension system in 2046 (Taiwan Association of University Professors 2016). The looming crisis notwithstanding, politicians have not taken decisive action to rationalize current benefit levels or raise indirect tax, fearing an electoral backlash. Considering that Taiwan still has sufficient room for raising indirect tax on goods and services (for instance, Taiwan's VAT rate is merely 5 percent which is one-fourth of the OECD average), this is not a matter of structural constraint. In addition to not biting the tax bullet to cope with the fiscal shortage, to make matters worse, the latest research has revealed that Taiwan has implemented various tax deductions and exemptions during both left- and right-leaning government periods—for example, offering tax relief for corporations’ goods and services (Lin Reference Lin2018).

Concluding remarks

The primary goal of this article has been to uncover the relationship between increasing levels of electoral democracy and welfare politics in new democracies, by examining how elections incentivize politicians to overpromise on social welfare policies. Using Taiwan as its case study, the legislation-based quantitative evidence presented has demonstrated politicians’ inclination to overpromise social welfare benefits during election periods; this pattern has increasingly become clear in tandem with the progression of electoral democracy and was particularly pronounced among legislative-branch members (compared to executive-branch ones), who are much more susceptible to electoral pressures. Drawing from the legislative, electoral, and welfare studies literatures, the article has attributed this phenomenon to the implicit incentives for politicians to abuse three types of cognitive bias on the voter side in the tendency to reward: politicians’ election-time performance, the provision of visible and relatable benefits, and policy promising without actual delivery.

In addition to the conventional perspective in the existing literature that views the positive effect of deepening electoral democracy (Shim Reference Shim2019)—meaning elites’ increasing prioritization of social welfare issues over other ones—the key findings here add important nuance by demonstrating the negative effect of increased electoral democracy on the politics of social welfare. That is, taking advantage of voters’ cognitive biases, competition incentivizes political parties to overpromise social welfare benefits.

To what extent are these findings generalizable? The key claim in this article can be tested with countries where political actors are not ideological constrained by the provision or curtailment of social welfare. Beyond Taiwan, another developed East Asian democracy, South Korea, clearly qualifies in this regard (Peng and Wong Reference Peng, Wong and Pierson2010; Shim Reference Shim2020); similarly, the analysis of overpromising welfare politics can be applied to several other new democracies. For instance, Poland and Hungary appear to be good candidates here in view of the fact that left-wing socialist parties there pushed for market reforms or the liberal reorganization of welfare-state institutions—such as introducing means-tested benefits, cutting spending, or accelerating privatization—during the 1990s, while right-wing parties called for increasing public spending or a return to communist-era welfare provisions (Morlang Reference Morlang, Curry and Urban2003; Curry Reference Curry, Curry and Urban2003). Similarly, numerous democracies in the Southeast Asian and MENA regions qualify as potential subjects of analysis—for example Indonesia and Tunisia, since research demonstrates that elite-level comparison between left and right-leaning parties shows no recognizable differences on the role of government vis-à-vis the market (Fossati et al. Reference Fossati, Aspinall, Muhtadi and Warburton2020; Farag Reference Farag2020).

Beyond applying the article's core argument to other countries, there are other potential avenues of future research. First, the research here can be extended to both the elite and voter levels. For the former, one can analyze whether overpromising on social welfare benefits does actually increase one's reelection chances. If so, to what extent and for which specific legislator types particularly? For the latter, a public-opinion survey might be conducted to examine whether voters are aware of politicians’ overpromising, and, if that is the case, what effects it has. Moreover, experiments could be run to examine whether the cognitive biases presumed in this article can be verified. Secondly, alternative explanations on why overpromising of social welfare benefits occur can be investigated. For instance, what is not tested in this article is the possibility that social welfare overpromising can be a bidding game between opposition and ruling party members. By tracing the proposed sequence of similar social welfare bills within a given time period, future research can add further insights into the political dynamics behind the legislative overpromising phenomena.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2021.29.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Tim Dorlach, Elena Korshenko, Marianne Ulriksen, Pieter Vanhuysse, Carina Schmitt, and Thomas Richter for helpful feedback on parts of the article. The suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers were particularly helpful. The research benefited immensely from presenting findings at DaWS Early Career Workshop, “Party Politics and Public Policies: New Perspectives on an Old Field” panel at Council of European Studies Conference, and Accountability and Participation research team meeting of the German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares none.

Jaemin Shim is an assistant professor at the Department of Government and International Studies at the Hong Kong Baptist University, and an associate fellow at the Institute of Asian Studies, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg, Germany. His primary research interests lie in democratic representation, comparative welfare states, gender, and legislative politics. His works have appeared or are forthcoming in international journals including Democratization, Parliamentary Affairs, European Political Science, and Journal of Legislative Studies.