INTRODUCTION

Can international human rights law cause greater state compliance with human rights norms in the absence of centralized enforcement? Due to the decentralized nature of international human rights law, many have questioned whether international legal commitments can lead to greater compliance with human rights norms. Studies have looked to domestic politics to suggest several potential mechanisms through which international law encourages state compliance. Many argue that human rights treaties empower domestic actors, such as the courts and civil society, to advocate for greater state compliance (Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Powell and Staton Reference Powell and Staton2009; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2005; Cardenas Reference Cardenas2007; Smith-Cannoy Reference Smith-Cannoy2012). Meanwhile, a handful of other studies examine whether international law can shape public perception and whether the public can ensure greater compliance through a constituency-driven domestic compliance mechanism (Chilton Reference Chilton2014a and Reference Chilton2014b; Wallace Reference Wallace2013 and Reference Wallace2014; Putnam and Shapiro Reference Putnam and Shapiro2017; Tomz Reference Tomz2008; Kreps and Wallace Reference Kreps and Wallace2016; Dai Reference Dai2005).

An important question remains, however: Why do domestic constituents care about compliance? This study finds that, at least in one particular bilateral, asymmetric treaty relationship, the public is concerned with the reputational consequences of noncompliance. South Korean constituents fear that other states would no longer be willing to make future agreements if their government were to renege on an existing treaty and thereby earn a reputation as a noncompliant state.

This study's findings can be summarized in three parts. First, this study finds that in an experimental setting, a single instance of past noncompliance can negatively affect first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance in a similar issue area. First-order beliefs are beliefs that one actor has about another actor's behavioral tendencies (i.e. what you think about me). Second-order beliefs are beliefs that one actor has about what others believe about the actor's behavioral tendencies (i.e. what I think you think about me).Footnote 1 A foreign public's first-order beliefs about a noncompliant state's future compliance are affected by the state's past compliance behavior. That is, if South Korea has not complied with a similar issue area in the past, Americans will believe that South Korea is less likely to comply in the future. Meanwhile, the domestic public's second-order beliefs about a foreign public's first-order beliefs are affected by past compliance behavior as well. That is, South Koreans are less likely to believe that Americans will expect South Korea to comply in the future, if South Korea has not complied with a similar issue area in the past. This result suggests a reputational concern motivating domestic public demand for compliance.

Second, the study finds that post-noncompliance, first-order beliefs about noncompliance are not very fungible, meaning one's reputation for noncompliance spills over to different areas of international law in decreasing increments as the issue area under consideration is further removed from the issue of the original violation. That is, American beliefs about future South Korean compliance increase as the issue area under consideration is further removed from the issue area of South Korea's past noncompliance. Americans are pessimistic about future South Korean compliance if South Korea has not complied in the past, but this pessimism about future South Korean compliance behavior does not easily extend to different areas of international law.

Third, unlike first-order beliefs, past noncompliance can negatively affect second-order beliefs about future compliance in different issue areas. South Korean citizens believe that their own state's noncompliance will create reputational spillovers to different areas of international law, even though an examination of American first-order beliefs suggests otherwise. If South Korea has not complied with a particular issue area in the past, South Koreans believe that Americans will be pessimistic about South Korean compliance in other issue areas, even though Americans are more optimistic about future South Korean compliance in other issue areas. In sum, if the issue area of noncompliance is sufficiently salient to capture the public's attention, this study suggests that the public's perceived reputational consequences of noncompliance can be one potential mechanism encouraging state compliance with international law.

THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL FOUNDATIONS

Due to the decentralized nature of the international legal order, many have questioned why states in anarchy comply with international human rights law (Downs, Rocke, and Barsoom Reference Downs, Rocke and Barsoom1996; Von Stein Reference Von Stein2005). Some argue that human rights treaties change domestic perceptions of human rights norms and that domestic actors, such as the courts and NGOs, can advocate for greater state compliance post-ratification (Simmons Reference Simmons2009; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui Reference Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui2005; Powell and Staton Reference Powell and Staton2009; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2005; Cardenas Reference Cardenas2007; Smith-Cannoy Reference Smith-Cannoy2012). On the other hand, some studies examine whether international human rights law can shift public perceptions and shape public discourse towards compliance (Chilton Reference Chilton2014a and Reference Chilton2014b; Wallace Reference Wallace2013 and Reference Wallace2014; Putnam and Shapiro Reference Putnam and Shapiro2017; Tomz Reference Tomz2008; Kreps and Wallace Reference Kreps and Wallace2016; Dai Reference Dai2005). Changed public perceptions could pressure policymakers and thereby ensure greater compliance through a constituency-driven domestic compliance mechanism. For both strands of research, a focus on public perception is warranted considering how courts, activists, and elected officials all rely on some public support in ensuring greater compliance with international law (Ron Reference Ron2017). Not surprisingly, there is growing body of literature focusing on public perceptions of human rights and public support for compliance with human rights (Koo Reference Koo2017; Valentino and Weinberg Reference Valentino and Weinberg2017; Barton, Hillebrecht, and Wals Reference Barton, Hillebrecht and Wals2017; Gerber Reference Gerber2017; Crow Reference Crow2017; Murdie and Purser Reference Murdie and Purser2017; Pandya and Ron Reference Pandya and Ron2017).

However, despite the increasing scholarly focus on public support for compliance, it is still unclear why the public cares about this issue. In other words, while it is becoming more evident that the public supports compliance with international human rights treaties, it is unclear why the public cares about compliance. One possibility is that the public cares about the substantive commitment made in the treaty. That is, the public cares about the norms codified in the international human rights treaties and supports compliance because those norms are aligned with their values. Another possibility is that the public supports compliance because it believes noncompliance will have negative reputational effects.

REPUTATION

Rationalists and constructivists both elaborate on reputation as a reason for why the public cares about compliance. Rationalists argue that international law can operate as a commitment device in a system of anarchy through beliefs about reputation for future compliance (Morrow Reference Morrow2014). If a state reneges on its treaty commitments, then foreign publics may form beliefs about the reneging state. More specifically, foreign publics may assign the reneging state a reputation for noncompliance based on past behavior, which may reduce their state's willingness to cooperate with the reneging state in the future. When a state's past behavior causes others to view the state negatively in such a manner, that state is said to incur a reputation cost (Brutger and Kertzer Reference Brutger and Kertzer2018). If the noncompliant state's constituents believe that their state will incur a reputation cost for noncompliance, they may demand compliance. Meanwhile, constructivists argue that the normative belief that agreements should be complied with, pacta sunt servanda, creates an incentive for states to comply with agreements and avoid developing a reputation as a noncompliant state (Simmons Reference Simmons2010). This study therefore examines whether post-noncompliance reputational concerns are driving public demand for compliance. Does past noncompliance affect public beliefs about future compliance?

Before continuing further, a precise definition for reputation is warranted. Reputation is a broad term that traditionally refers to any belief about an actor or his or her behavioral tendencies based on the actor's past actions (Dafoe, Renshon, and Huth Reference Dafoe, Renshon and Huth2014). A state may assign other states a reputation to predict their future behavior (Mercer Reference Mercer1996). States can get assigned a reputation for many different traits or behavior such as a reputation for resolve, for fulfilling threats, for hostility, and for greed (Dafoe, Renshon, and Huth Reference Dafoe, Renshon and Huth2014). Much of the literature on reputation focuses on reputation for resolve, rather than reputation for treaty compliance (Schelling Reference Schelling1966; Tang Reference Tang2005; O'Neill Reference O'Neill1996 and Reference O'Neill2006; Kagan Reference Kagan1996; Lebow Reference Lebow2008; Walt Reference Walt2015; Huth Reference Huth1997; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2016; Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo Reference Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo2015). Some research on reputation for resolve suggests that political elites care deeply about their own state's reputation and believe their actions will have far-reaching reputational consequences (Schelling Reference Schelling1966; Tang Reference Tang2005; O'Neill Reference O'Neill1996 and Reference O'Neill2006; Kagan Reference Kagan1996; Lebow Reference Lebow2008; Walt Reference Walt2015). However, others argue that when policymakers predict the credibility of other states’ threats, they rely on present day behavior rather than reputation based on the other states’ past behavior (Press Reference Press2005; Hopf Reference Hopf1994). Snyder and Borghard (Reference Snyder and Borghard2011) do not find strong evidence of reputation for resolve having a significant influence on elite decision-making, partly because elites rarely issue threats that are clear or commit the state's reputation in the first place.

While drawing on the theoretical implications of the divergent findings of past studies, I focus on reputation for treaty compliance rather than reputation for resolve, and whether the public, rather than elites, hold beliefs about reputation costs. This research focus is pertinent not only because of the aforementioned domestic compliance mechanisms that begin with public perceptions about international law, but also because of the nature of international legal commitments. Unlike reputation for resolve, where threats are not always clear, states should theoretically pay a high reputation cost for noncompliance with international treaties because when states sign a treaty or make a legal commitment, they do so in plain sight for all to see. Both the domestic public and the international community observe the commitment. International legal commitments also leave a paper trail that reduces the opportunity for deniability. They are essentially “the most solemn pledge a state can make” and a “maximal pledge of reputation” (Guzman Reference Guzman2008, 59; Lipson Reference Lipson2003; Simmons and Hopkins Reference Simmons and Hopkins2005). As such, the public should also be theoretically more likely to assign states with a reputation for treaty compliance based on post-ratification compliance behavior.

QUESTIONS POSED

In order for reputational concerns to be motivating public demand for compliance and thereby fueling the aforementioned domestic compliance mechanisms, a few key aspects of the reputational logic must be addressed. First, domestic constituents’ beliefs about how other foreign publics perceive the constituency's own state must be affected by the state's past noncompliance. In other words, reputational logic requires that second-order beliefs—beliefs one actor has about what others believe about the actor's behavioral tendencies (i.e. what a noncompliant state's public believes about a foreign public's beliefs about the noncompliant state's future compliance)—are influenced by the past compliance behavior of one's own state. However, we have yet to systematically test whether the public believes that foreign publics will draw reputational inferences from the state's noncompliance with international law. As mentioned above, past studies have focused on elites and reputation for resolve to arrive at differing conclusions about the impact of reputation. It is also unclear whether first-order beliefs (i.e. what a foreign public believes about the noncompliant state's future compliance) are affected by past noncompliance. This study addresses these gaps by first exploring whether noncompliance affects the public's first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance.

Second, reputation costs should be fungible for reputational concerns to motivate public demand for compliance more broadly. The domestic public must believe that foreign publics will view reputation for compliance to be linked across different issue areas and therefore predictive of compliance behavior more broadly. If members of the public do not think that a foreign state's compliance with issue x at time t tells them anything about the same state's compliance with y at time t + 1, then beliefs about reputation are less likely to result in public demand for compliance. That is, if the public does not consider reputation for issue x as linked with a different issue y, then the public's beliefs should only impact the assessment of future compliance behavior regarding that specific issue area x, reducing the public's perceived need and demand for compliance. Whether issues are linked and the extent to which reputation is fungible are a source of active scholarly debate (Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo Reference Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo2015; Hopf Reference Hopf1994; Snyder and Diesing Reference Snyder and Diesing1977). However, the focus of past studies has been on elites and these studies have arrived at different conclusions as to whether reputational inferences spill over to other issue areas. This study is the first, at least to my knowledge, to examine whether the public believes reputation for compliance in one particular issue area is linked to other issue areas of international law.

Third, this study explores the possibility of divergence between first-order and second-order beliefs. There is no reason, after all, for first-order and second-order beliefs to perfectly match all the time (Dafoe, Renshon, and Huth Reference Dafoe, Renshon and Huth2014). Past research on reputation, specifically the reputation for resolve, suggests that political elites believe that other states will draw reputational inferences while they themselves do not draw reputational inferences of others (Tang Reference Tang2005). Tang (Reference Tang2005) refers to this paradoxical elite behavior as the “cult of reputation,” where leaders are consistently preoccupied with the reputational consequences of their actions, even though they do not draw reputational inferences from other states’ behavior. Tang writes, “[A]lthough a state constantly fears that others may assign reputation to it based on its past behavior, the state never assigns reputation to other states based on their past behavior” (Tang Reference Tang2005, 42). Such studies suggest a potential for divergence between first-order and second-order beliefs in regards to issue-linkage, where the public's second-order beliefs are affected by past noncompliance in different issue areas, due to the public's constant concern about their state's own reputation, while the public's first-order beliefs are not affected by past noncompliance in different issue areas. That is, reputational concerns may not be sufficiently salient to permeate across issue areas for first-order beliefs, but they may be sufficiently salient to permeate across issue areas for second-order beliefs.Footnote 2

Studies on motivated reasoning also suggest the possibility of divergence. According to Mercer's (Reference Mercer1996) attribution-based framework for reputational inferences, leaders make reputational inferences differently depending on whether the foreign state is in the in-group or the out-group. Leaders have varying expectations for allies and adversaries; they are more forgiving of states in the in-group or allies, but less forgiving of states in the out-group or adversaries. Drawing on past studies of elites, given that the noncompliant state is a treaty partner, and thus a member of the in-group, foreign publics may try to reconcile their beliefs about a state willing to ratify a treaty and the state's subsequent noncompliance by attributing the instance of noncompliance to issue-specific circumstances. That is, in order to resolve the dissonance between a treaty partner who has failed to follow through, foreign publics may be more willing to “explain away” the noncompliance as a momentary lapse and not link future compliance in different issue areas to the instance of past noncompliance in a particular issue area. In contrast, the domestic public of a noncompliant state may assume the worst, along the lines of Tang's (Reference Tang2005) cult of reputation, and believe that foreign publics will draw reputational inferences across issue areas. This study thus explores whether foreign publics consider another state's past noncompliance as less indicative of the state's future compliance in different issue areas and whether the domestic public of the noncompliant state nonetheless believes that foreign publics will link different issues areas.

METHODS

I conducted cross-national surveys in South Korea and the United States that served as mirrors of each other to explore the impact of past noncompliance on the formation of first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance. Survey experiments were ideal for this study because reputation costs are considered the “dark matter of international relations” (Dafoe and Caughey Reference Dafoe and Caughey2016, 372) and difficult to study in an uncontrolled environment in which leaders avoid incurring reputation costs (Brutger and Kertzer Reference Brutger and Kertzer2018). The experimental setting allowed for the manipulation of the key variables—compliance or noncompliance behavior and the issue area being considered for future cooperation—while holding other variables constant.

SURVEY TEXT AND HYPOTHESES

To elaborate further, I first estimated the impact of noncompliance versus compliance on first-order beliefs and second-order beliefs about the likelihood of a noncompliant state's future compliance. This first step allowed me to estimate the effect of noncompliance against the compliance treatment condition. The exact procedure is as follows. All US respondents read a hypothetical vignette that South Korea had signed a security treaty with the United States, which included a stipulation about the humane treatment of prisoners of war (POWs). Respondents were then told of South Korean noncompliance (i.e. noncompliance treatment group) or compliance (i.e. compliance treatment group) with the treaty. Respondents in the noncompliance treatment group were told that although South Korea had ratified the treaty, there was conclusive evidence that South Korea violated the agreement by torturing North Korean covert operatives who were captured after infiltrating the border into South Korean territory.Footnote 3 Respondents in both groups were then told of the possibility of signing a new treaty in a different issue area within the domain of the laws of war—the preservation of artifacts during war. All respondents were then asked whether they believed South Korea would abide by the new agreement if signed. More precisely, U.S. respondents read one of the following versions.

Our ally South Korea previously signed a security treaty with our country. In the security treaty, South Korea made a formal commitment not to mistreat POWs for a military advantage. The security agreement created an independent organization to observe the treatment of POWs.

[Noncompliance treatment: The organization recently reported that South Korea violated the security treaty when dealing with captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border in the past few years.]

[Compliance treatment: The organization recently reported that South Korea faithfully followed through with the treaty. Whenever South Korea captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border, they were treated in accordance with the international treaty.]

The US is now considering a new security agreement with South Korea that would prohibit South Korea from destroying historical artifacts and monuments during war. The new security agreement does not deal with POWs. Instead, the new security agreement deals with the preservation of historical artifacts during war. The new security agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor historical sites. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting the destruction of historical artifacts and monuments in the past.

How likely do you think South Korea will stick to the agreement if signed?

Next, the South Korean survey posed the same vignette and asked Korean respondents about the extent to which they thought Americans would trust South Korea to abide by a new agreement regarding the preservation of artifacts, given South Korean noncompliance or compliance. The South Korean survey thus measured second-order beliefs.

[Translated from Korean; the original Korean survey text is included in the Supplementary Materials to this article]

The United States previously signed a security treaty with our country. In the security treaty, our country made a formal commitment not to mistreat POWs for a military advantage. The security agreement created an independent organization to observe the treatment of POWs.

[Noncompliance treatment: The organization recently reported that our country violated the security treaty when dealing with captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border in the past few years.]

[Compliance treatment: The organization recently reported that our country faithfully followed through with the treaty. Whenever our country captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border, they were treated in accordance with the international treaty.]

The US is now considering a new security agreement with our country that would prohibit our country from destroying historical artifacts and monuments during war. The new security agreement does not deal with POWs. Instead, the new security agreement deals with the preservation of historical artifacts during war. The new security agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor historical sites. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting the destruction of historical artifacts and monuments in the past.

How likely do you think Americans will believe our country to stick to the new agreement if signed?

Given the literature on reputation for resolve suggesting that states incur a reputation for past behavior (Schelling Reference Schelling1966; Tang Reference Tang2005; O'Neill Reference O'Neill1996 and Reference O'Neill2006; Kagan Reference Kagan1996; Lebow Reference Lebow2008; Walt Reference Walt2015), I made the following hypotheses regarding reputation for treaty compliance. I expected US first-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance to be negatively affected by South Korea's past noncompliance. I also expected South Korean second-order beliefs about US beliefs about future South Korean compliance to be negatively affected by South Korea's past noncompliance.

H1 (first-order beliefs post-noncompliance): US respondents will be less likely to believe that South Korea will comply with a new treaty post-noncompliance than post-compliance.

H2 (second-order beliefs post-noncompliance): South Korean respondents will be less likely to believe that Americans will believe South Korea will comply with a new treaty post-noncompliance than post-compliance.

Second, in a separate stage of the experiment, I explored post-noncompliance issue-linkage by adding two noncompliance treatment conditions. Respondents were told, post-noncompliance, that the new agreement was in the same exact issue area, a different issue area within the domain of the laws of war (i.e. the noncompliance treatment condition from above), or an issue area outside the domain of the laws of war, all post-noncompliance. That is, the issue area of the new treaty moved progressively further away from the issue of the original treaty to test whether noncompliance with one issue was linked with similar and dissimilar issues. Respondents were told that the United States and South Korea were considering signing a new treaty on POWs, a new treaty on the preservation of artifacts during war, or a new treaty on the prohibition on trade tariffs on select goods. By holding South Korean noncompliance constant, and instead varying the issue area of the future treaty, I could test the extent of issue-linkage for both first-order and second-order beliefs. All of the treatment conditions specified whether the issue area of the new treaty was within or beyond the domain of the original treaty. Figure 1 summarizes all of the treatment conditions.

Figure 1 Treatment conditions

The respondents read one of the following versions.

For the US:

Our ally South Korea previously signed a security treaty with our country. In the security treaty, South Korea made a formal commitment not to mistreat POWs for a military advantage. The security agreement created an independent organization to observe the treatment of POWs. The organization recently reported that South Korea violated the security treaty when dealing with captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border in the past few years.

[POW treatment: The US is now considering a new security agreement with South Korea that would prohibit South Korea from mistreating POWs. The new security agreement will allow the independent organization to continue observing the treatment of POWs.]

[Artifact treatment (noncompliance treatment from above): The US is now considering a new security agreement with South Korea that would prohibit South Korea from destroying historical artifacts and monuments during war. The new security agreement does not deal with POWs. Instead, the new security agreement deals with the preservation of historical artifacts during war. The new security agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor historical sites. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting the destruction of historical artifacts and monuments in the past.]

[Tariff treatment: The US is now considering a new trade agreement with South Korea. The trade agreement would prohibit South Korea from imposing harmful trade tariffs on select US exports entering South Korea. The new trade agreement does not deal with POWs or war. Instead, the agreement deals with the separate area of international trade and commerce. The trade agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor trade between the two countries. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting attempts to impose tariffs in the past.]

How likely do you think South Korea will stick to the agreement if signed?

For South Koreans:

[Translated from Korean; the original Korean survey text is included in the Supplementary Materials]

The United States previously signed a security treaty with our country. In the security treaty, our country made a formal commitment not to mistreat POWs for a military advantage. The security agreement created an independent organization to observe the treatment of POWs. The organization recently reported that our country violated the security treaty when dealing with captured North Korean special forces (spies) who had infiltrated the border in the past few years.

[POW treatment: The US is now considering a new security agreement with our country that would prohibit our country from mistreating POWs. The new security agreement will allow the independent organization to continue observing the treatment of POWs.]

[Artifact treatment (noncompliance treatment from above): The US is now considering a new security agreement with our country that would prohibit our country from destroying historical artifacts and monuments during war. The new security agreement does not deal with POWs. Instead, the new security agreement deals with the preservation of historical artifacts during war. The new security agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor historical sites. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting the destruction of historical artifacts and monuments in the past.]

[Tariff treatment: The US is now considering a new trade agreement with our country. The trade agreement would prohibit our country from imposing harmful trade tariffs on select US exports entering our country. The new trade agreement does not deal with POWs or war. Instead, the agreement deals with the separate area of international trade and commerce. The trade agreement will allow an independent organization to monitor trade between the two countries. The monitoring organization has been successful in detecting attempts to impose tariffs in the past.]

How likely do you think Americans will believe our country to stick to the new agreement if signed?

Based on the literature suggesting that leaders do not draw reputational inferences across domains (Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo Reference Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo2015; Hopf Reference Hopf1994; Snyder and Diesing Reference Snyder and Diesing1977), as well as the literature on motivated reasoning (Mercer Reference Mercer1996), I made the following hypotheses regarding first-order beliefs and issue-linkage. I expected US first-order beliefs to be less affected by past South Korean noncompliance in different issue areas. That is, I expected US beliefs about future South Korean compliance in a particular issue area to be less affected by past South Korean noncompliance in other issue areas.

H3 (first-order beliefs and issue linkage): US respondents will be less likely to believe that South Korea will comply with a new treaty on the same issue as the original violation (POW treaty) than a new treaty on a separate issue within the same domain as the original violation (Artifact treaty).

H4 (first-order beliefs and issue linkage): US respondents will be less likely to believe that South Korea will comply with a new treaty on a separate issue within the same domain as the original violation (Artifact treaty) than a new treaty on a separate issue outside the domain (Tariff treaty).

Meanwhile, based on the literature suggesting that political elites believe that other states will draw reputational inferences while they themselves do not draw reputational inferences of others (Tang Reference Tang2005; Dafoe, Renshon, and Huth Reference Dafoe, Renshon and Huth2014), I expected second-order beliefs to be strongly affected by noncompliance in different issue areas. I expected that, due to the public's concern about their own state's reputation, the public's second-order beliefs would be strongly affected by past noncompliance in different issue areas. In other words, I expected South Korean beliefs about US beliefs about future South Korean compliance to be affected by past South Korean noncompliance in other issue areas. The hypotheses are also depicted in Figure 2.

H5 (second-order beliefs and issue linkage): The South Korean public's second-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance with a new treaty on the same issue as the original violation (POW treaty) will be similar to South Korean second-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance with a new treaty on a separate issue within the same domain as the original violation (Artifact treaty).

Figure 2 Hypothesized Spillover Effects of Noncompliance

H6 (second-order beliefs and issue linkage): The South Korean public's second-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance with a new treaty on a separate issue within the same domain as the original violation (Artifact treaty) will be similar to South Korean second-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance with a new treaty on a separate issue outside the domain (Tariff treaty).

SAMPLE DEMOGRAPHICS

Relevant demographic characteristics were collected for later analysis. These included standard demographic characteristics widely used in the literature such as age, gender, education level, employment status, income, and race (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2005). In addition, I measured political ideology, knowledge level, and political activism using standard questions from the American National Election Studies [ANES].Footnote 4 Other relevant predispositions also drawn from existing studies included levels of cooperative internationalism, militant internationalism, and isolationism (Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun, and Iyer Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014).Footnote 5 To be clear, due to the randomization of the treatment assignment, statistical models involving covariates are not necessary for estimating unbiased treatment effects (Wallace Reference Wallace2013; Mutz and Permantle Reference Mutz and Pemantle2015). Therefore, the main models in the following analyses do not include the covariates, and models controlling for covariates are included only as robustness checks.

The surveys involved a sample of 1,098 American citizens and 1,000 South Korean citizens. The survey of Americans was conducted through Amazon Mechanical Turk [MTurk] on October 22 and 23, 2016, and the survey of South Koreans was conducted by a professional polling firm Macromill Embrain from November 16 to November 22, 2016. Sample characteristics for US respondents and Korean respondents used in this study have been provided in the Supplementary Materials. It should be noted that typicl American MTurk samples are typically not nationally representative, and they tend to over-represent younger, liberal, lower income individuals while under-representing Hispanics and African Americans. This is the case here: the study's US sample slightly over-represents liberals while under-representing Hispanics and African Americans. However, all of the following results using the US MTurk sample can be replicated using post-stratification weights to account for deviations from a nationally representative sample. These results have also been reproduced in the Supplementary Materials as robustness checks.Footnote 6 Meanwhile, Macromill Embrain ensured that the South Korean sample was representative on key demographic characteristics such as gender, political ideology, age, and education. The outcome measures—whether US respondents believed South Korea would comply and whether South Korean respondents believed that Americans would believe South Korea would comply—were measured on a 7-point Likert scale but converted to percentage points for analysis.Footnote 7

CASE SELECTION

The selection of an actual state, South Korea, as the counterpart to the US had several methodological advantages. Using a real state, as opposed to a hypothetical state, allowed respondents to bring in their prior beliefs about the dyad. As such, this experimental setup mimicked a more realistic setting in which respondents update their prior beliefs about a specific state based on new information to guide their final decision. Using a hypothetical state for which respondents do not have any priors about compliance behavior would have exaggerated the effect of any single instance of noncompliance. It should be made clear, though, that using actual states did not mirror reality perfectly since in reality people are often bombarded with new information that can drown out the effect of any single instance of compliance or noncompliance. However, survey experiments are rarely, if ever, able to mimic reality precisely. Using a dyad grounded in reality mitigated concerns about validity somewhat by allowing prior beliefs to play a role. At the very least, this experimental setup allowed for findings about the effect of noncompliance on the margins.

Viewed more reasonably, the selection of these two particular states also allowed for a deeper exploration of US–South Korean relations, which is a worthwhile endeavor in itself. The US and South Korean conceptions of reputation costs as it pertains to their bilateral relationship have far-reaching geopolitical implications, given their close military alliance and the numerous bilateral agreements to which the two states are party. In addition, the asymmetric nature of the US–South Korean relationship allowed for potential insights about how power discrepancies may affect each polity's perception of the reputation costs in an unequal bilateral relationship, if not in bilateral relationships more generally.

Moreover, in designing the experiment, it was essential that respondents from both states accepted the premise of the treatment and found the hypothetical to be plausible. The torture of POWs is an issue that receives much media attention in reality, and the hypothetical case had to concern a state that concealed its treatment of POWs and simultaneously faced a sufficiently dire security threat to have a strong incentive to engage in torture. Fortunately for the purposes of this study, the actual treatment of captured North Korean covert operatives by South Korean officials is confidential. While South Korean security forces often capture North Korean operatives in South Korea, it is unclear what type of treatment these operatives are subjected to. Moreover, because of the unique national security threat South Korea faces from its North Korean neighbors, South Korea has an incentive to engage in enhanced interrogation techniques. Such factors gave the vignette a degree of plausibility. The reverse case in which the United States was the noncompliant state was precluded due to similar concerns about plausibility.

Other premises of the vignette, namely as the existence of a security treaty, were also plausible given the military alliance the two states have shared for decades. The particular treatment condition that stated that the two states were considering a new trade treaty also reflected reality. There were lengthy negotiations about trade practices between the two states, followed by the eventual ratification of the US–South Korea Free Trade Agreement, which was being hotly debated in South Korea at the time of the survey. In short, ensuring the plausibility of the vignette in order to mitigate the risk of respondents rejecting the premise of the treatment dictated the choice of South Korea as the counterpart to the United States.

While the selection of actual states helped the experiment mimic reality by allowing priors to play a role and to probe deeper into the US–South Korean relationship, selecting these two states for this survey also had its disadvantages, specifically in terms of generalizability. This study's findings may be limited to asymmetric dyads. Yet a large number of the treaty commitments made by the US involve asymmetric dyads anyway. The prevalence of US treaty commitments alone likely justifies the study's relevance despite its limited generalizability. One could argue that the resulting treatment effects are also dyad-specific. That is, the case selection may limit the generalizability of the findings to that of the US–South Korea dyad and at most an asymmetric bilateral relationship. Reactions to the treatments could have been tempered by dyad-specific biases, such as feelings of mutual trust that have developed between the two countries over the past few decades. On the other hand, some Korean respondents, influenced by rising tensions between the two states and strong anti-American sentiments, could have instead allowed their preconceived notions to color their perception of how Americans may respond to South Korean noncompliance. Some US respondents could have been abnormally influenced by the perception that their allies are not doing their fair share in securing their own national security. Within segments of the American populace, there is a widely held belief that American allies such as South Korea are “free-loading”— benefitting from American military commitments while giving nothing in return. During the 2016 presidential election, then-candidate Donald Trump noted how the United States gets “practically nothing” in return for protecting South Korea (Pruitt Reference Pruitt2016). Such concerns may have negatively affected American first-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance behavior in ways that are not generalizable to other states.

It is also possible that differences in post-noncompliance beliefs about future compliance across different issue areas were due to differing baseline expectations about compliance in certain issue areas, rather than decreasing issue-linkage. For instance, Americans may have believed that South Korea was more likely to comply with a tariff treaty than an artifact treaty due to general expectations about compliance with tariffs and therefore have a greater belief in South Korea's future compliance with the tariff treaty. Such an explanation would suggest that issue-linkage and past noncompliance do not play a significant role. To mitigate some of the concerns, I asked opened-ended questions afterwards, which are discussed below and in the Supplementary Materials.

Finally, this study's case selection cannot account for the possibility that cross-national differences between first-order and second-order beliefs were due to baseline differences between Americans and South Koreans about issue-linkage. It is possible that Americans do not believe in issue-linkage while South Koreans do. However, there is no obvious theoretical reason to expect such baseline differences between Americans and South Koreans. Rather, one would theoretically expect the publics of all countries to hold similar attitudes towards issue-linkage, and the results are more likely a reflection of the difference between first-order and second-order beliefs. Nonetheless, to address these concerns, a future study could hold constant the state and measure first-order and second-order beliefs from people of the same state. For instance, one could imagine a survey of American first-order beliefs post-South Korean noncompliance and another separate survey of American second-order beliefs about South Korean beliefs post-American noncompliance. Such a research design, of course, would have to resolve plausibility concerns that were carefully addressed in this study's research design.

Overall, the benefits of mimicking reality and reducing the risk of respondents rejecting the premise of the treatment outweighed concerns about generalizability and ultimately motivated the case selection of South Korea and the United States. The more skeptical reader may interpret the following results as applying only to one specific dyad or asymmetrical bilateral relationships, as opposed to bilateral relationships more generally.

RESULTS

First, I estimated the effect of noncompliance on first-order beliefs using an OLS model. Comparing the compliance treatment to the noncompliance treatment, both of which considered future compliance regarding the same issue area (i.e. preservation of artifacts), noncompliance decreased first-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance by 23.3 percentage points. Noncompliance also decreased South Koreans’ second-order beliefs about future compliance by 12.6 percentage points. The results are summarized in Figure 3 and Table 1. In short, I found support for my first hypothesis regarding first-order beliefs about compliance and for my second hypothesis regarding second-order beliefs about compliance. Past noncompliance decreases first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance.

Figure 3 Estimated Effects of Noncompliance (OLS)

Table 1 Estimated Effects of Noncompliance on First-Order and Second-Order Beliefs (OLS)

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Note: The reference group is the compliance treatment group. Not all pre-treatment covariates that were used in estimating each state's respective Model 2 have been shown above. Additional pre-treatment covariates not shown above are age, education, employment status, income, race (for US only), and political involvement. Political ideology represents individual respondents’ political leaning with 0 being liberal and 1 being conservative. The dependent variable has been converted to percentage points. For first-order beliefs (US), 1 signifies a 100 percentage point increase in US respondents’ beliefs regarding the likelihood of South Korea's future compliance. For second-order beliefs (South Korea), 1 signifies a 100 percentage point increase in South Korean respondents’ beliefs regarding U.S. beliefs about the likelihood of future South Korean compliance.

All results are robust to models that control for pre-treatment covariates. Proportional odds models often used for Likert scale responses resulted in similar findings have been reproduced in the Supplementary Materials for these models and all subsequent models. It should be noted that a comparison of the magnitude of the treatment effects between the two countries (23.3 versus 12.6 percentage points) is misleading because cross-national differences in cell means could be the result of differences in the translation of the survey questions or a variety of other confounding factors. Rather, the takeaway should be that noncompliance, as opposed to compliance, leads to reduced first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance.

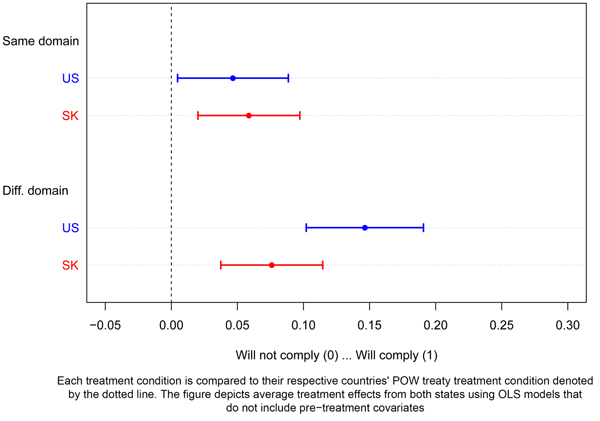

Next, I compared the post-noncompliance treatment outcomes to each other in order to estimate the extent of issue-linkage, holding constant past noncompliance behavior. First, the following analyses using an OLS model reveal low issue-linkage for first-order beliefs in the US. While noncompliance will negatively affect first-order beliefs about a noncompliant state's future compliance behavior, respondents are more likely to believe that South Korea will comply in the future as one moves further away from the issue of the original noncompliance. Treatment conditions (i.e. issue areas) that were hypothesized to be comparably less affected by past noncompliance were in fact less affected. A new treaty in a different issue area in the same domain as the original noncompliance—a new treaty about the preservation of artifacts during war which is in the domain of a security treaty—increased US first-order beliefs regarding future South Korean compliance, compared to a new treaty in the same issue area as the original violation. The difference was a statistically significant 4.7 percentage points. A new treaty in a different issue area in a separate domain—a new treaty on trade tariffs, which is in the domain of trade not security—increased US first-order beliefs in future South Korean compliance, compared to a new treaty in a different issue area in the same domain as the original violation. The difference was a statistically significant 10.0 percentage points. In sum, first-order beliefs about future compliance are less affected by past noncompliance in different issue areas.

Unlike first-order beliefs, second-order beliefs have higher issue-linkage. Second-order beliefs—what South Koreans believed about US beliefs about future South Korean compliance—seemed to be affected by past noncompliance in related and unrelated issue areas, even though US first-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance were not affected by past compliance in different issue areas. As Table 2 and Figure 4 demonstrate, among South Korean respondents, treatment conditions (i.e. issue areas) that were hypothesized to be comparably less affected by past noncompliance were not always less affected. A new treaty in a different issue area in the same domain—the preservation of artifacts during war, which is in the domain of a security treaty—increased South Korean second-order beliefs, compared to a new treaty in the same issue area as the original violation. The difference was a statistically significant 5.9 percentage points. However, once moving beyond the issue of original violation, and comparing separate issues across domains, South Koreans did not believe Americans would distinguish between separate domains. Instead, they believed that Americans would maintain a constant level of skepticism about future compliance. Second-order beliefs about future South Korean compliance for a new treaty in a different issue area in a separate domain—a new treaty on trade tariffs which is in the domain of trade not security—was statistically indistinguishable to second-order beliefs about a new treaty in a different issue area in the same domain as the original violation. The difference was a statistically insignificant 1.7 percentage points. To summarize, I failed to find evidence for my fifth hypothesis regarding comparable second-order beliefs about compliance for different issue areas within the same domain. However, I did find strong evidence for my sixth hypothesis regarding comparable second-order beliefs about compliance for different issue areas in separate domains. Once a state fails to comply, its constituents believe that their state has lost much credibility on the issue of the original violation, and they also believe that their state has incurred a consistent loss in credibility in different other issue areas, no matter how far removed these issues are from the original violation.

Figure 4 Estimated Spillover Effects of Noncompliance (OLS)

Table 2 Estimated First-Order and Second-Order Spillover Effects (OLS)

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note: The reference group is the noncompliance treatment group that considers the same issue as the original treaty, post-noncompliance. Not all pre-treatment covariates that were used in estimating each state's respective Model 2 have been shown above. Additional pre-treatment covariates not shown above are age, education, employment status, income, race (for US only), and political involvement. Political ideology represents individual respondents’ political leaning with 0 being liberal and 1 being conservative. The dependent variable has been converted to percentage points. For first-order beliefs (US), 1 signifies a 100 percentage point increase in U.S. respondents’ beliefs regarding the likelihood of South Korea's future compliance. For second-order beliefs (South Korea), 1 signifies a 100 percentage point increase in South Korean respondents’ beliefs regarding U.S. beliefs about the likelihood of future South Korean compliance.

I now turn to differences between first-order and second-order beliefs. As mentioned earlier, a simple comparison of cell means across states is not appropriate. Cross-national differences in cell means could be the result a variety of confounding factors between the two states. Instead, I compared the differences in the treatment effects within each state. As Figures 4 and 5 show, South Koreans believed that Americans would treat separate domains equally and would not draw a distinction between separate domains. In actuality, Americans did take into account different domains and treated separate issues and domains with progressively smaller reputational spillovers.

Figure 5 Estimated Spillover Effects of Noncompliance

One key limitation of this study should be addressed. As mentioned above, it is possible that differences in post-noncompliance beliefs about future compliance across different issue areas were due to differing baseline expectations about compliance in certain issue areas, rather than decreasing issue-linkage. To address this concern, the experiment asked respondents to provide open-ended responses about the reasoning for their decisions. Respondents in all treatment groups were prompted to provide a reasoning for their beliefs about compliance. Using structural topic models, I then identified several common reasonings (i.e. “topics”) provided by the respondents and afterwards determined which treatment condition was more likely to trigger certain reasonings. In short, I found some evidence that past noncompliance affected first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance due to reputational concerns, not due to varying baseline beliefs about compliance in certain issue areas.

For first-order beliefs, American respondents assigned to noncompliance treatment groups, who were progressively more likely to believe in future South Korean compliance as the issue area was further removed from the original violation, were more likely to justify their beliefs by citing how they viewed different issue areas as separate issues in which previous noncompliance mattered less, not by citing different baseline expectations about compliance in a particular issue area. For instance, one US respondent who received the noncompliance treatment about a new treaty in a different issue area as the original violation reasoned that “I think that they [South Korea] will uphold their [new] deal with the US and the treatment of North Korean POWs is unrelated,” rather than reasoning that it was easier to comply with an artifact treaty than a POW treaty.

Table 3 Estimated Spillover Effects of Noncompliance (OLS)

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note: The table notes baseline support for compliance and average treatment effects from OLS models that do not include pre-treatment covariates.

For second-order beliefs, Korean respondents, who mostly demonstrated a constant level of skepticism across different domains once moving beyond the issue of the original violation, often reasoned that they weighed the previous violation equally regardless of the domain of the new treaty. For instance, one South Korean respondent wrote that “If we [South Korea] did not keep the original treaty, even if we made a new treaty they [US] would not think that we would not comply well. We already lost their trust.” Although there is some anecdotal evidence of differences in baseline expectations for each issue area, it appears overall that the estimated treatment effects stem from past noncompliance and diverging beliefs about issue-linkage, rather than diverging baseline expectations. The exact methodology and full results are reproduced in the Supplementary Materials.

CONCLUSION

Much of the reputation literature focuses on the reputation for resolve and the tendency among policymakers to exacerbate tensions due to reputational concerns. In the context of resolve, reputation is seen as a problem plaguing international politics. It deepens rivalries and prolongs conflicts because leaders are preoccupied with demonstrating their willingness to fight, not only now but also in the foreseeable future. On the other hand, there is much less scholarly focus on reputation for compliance, despite the strong belief in the reputational mechanism serving as a source for good, a commitment device of sorts to international law. Therefore, this study focuses on one particular bilateral relationship—that between the US and South Korea—to examine reputation for compliance and explore whether the public's concern with reputational consequences can foster greater adherence to international commitments, thus strengthening the international legal order.

In short, this study first finds that noncompliance—compared to compliance—may reduce the public's first-order and second-order beliefs about future compliance. This finding supports the claim that the findings of a large body of literature on elite perceptions of reputation costs in the context of reputation for resolve may similarly apply to public perceptions of reputation costs in the context of reputation for compliance.

Second, this study compared first-order and second-order beliefs between the US and South Korea. The US survey suggested that first-order beliefs about compliance could be characterized as having low issue-linkage, meaning there were progressively smaller spillovers across issue areas and across domains. Americans, when informed of South Korean noncompliance in a particular issue area, were less inclined to believe in future South Korean compliance, but they tempered their skepticism if the new issue area under consideration was different from the issue area of the original violation.

On the other hand, there was difference in the degree of issue linkage between second-order beliefs and first-order beliefs. Second-order beliefs were heavily influenced by noncompliance in different issue areas, even though first-order beliefs were not. Although Americans were more forgiving of past noncompliance in different issue areas, South Koreans seemed to believe that their state would incur a reputation cost in different domains. The implication of this finding is that constituents of noncompliant states may mistakenly assume that their state's noncompliance will result in a substantial reputation cost and may demand compliance with existing treaties, fearing first-order reputation costs that are actually unwarranted in reality.

This cross-national discrepancy between first-order beliefs of Americans and second-order beliefs of South Koreans provides promising avenues for future research. To be clear, South Koreans believe that noncompliance will result in reduced US beliefs about future South Korean compliance in different domains. However, Americans are in fact more optimistic about future South Korean compliance in different domains despite South Korea's past noncompliance. A future study could further explore the causes behind this cross-national discrepancy. It is possible that there is a degree of motivated reasoning on the part of Americans. Because all treatments are post-ratification, and because the US is close allies with South Korea, Americans, unlike South Koreans, may be trying to reconcile their existing beliefs about South Korea's longstanding status as a close ally by explaining away the single instance of noncompliance to issue-specific circumstances. In order to resolve the dissonance between what Americans may be assume to be true of South Koreans—given the fact that the two states have already signed a treaty—and Korean noncompliance, it appears that Americans may be more willing to forgive South Koreans, and forgive them to a greater extent than South Koreans assume Americans will forgive. To explore this further, one could vary the target state to be a perceived out-group, which would serve as a foil to the perceived in-group South Korea.

The asymmetrical nature of the US–South Korea relationship should also be explored as a potential reason for the cross-national discrepancy. The case selection of the US–South Korean relationship was an opportunity to consider not only how these two specific states perceive of reputation costs but also how states in asymmetrical bilateral relationships perceive of reputation costs. Similar to many other junior partners of the US, South Korea relies on its military alliance with the US to fend off an existential threat, while the US does not. It is possible that because of the asymmetric relationship, the US public was not as concerned with the noncompliance of its junior partner, one of many junior partners, but South Koreans were especially concerned about their primary military ally's perception of their noncompliance. For South Koreans, the fear of US derogation from a critical military alliance may have exaggerated the perceived reputational consequences of their own noncompliance. A future study might fruitfully explore whether the observed cross-national discrepancy was the result of the asymmetrical nature of the relationship by comparing dyads with relatively equal power and unequal power.

Moreover, a future study could examine discrepancies in first-order and second-order beliefs post-compliance, rather than post-noncompliance. Does a state's past compliance lead foreign publics to have more optimistic first-order beliefs about the compliant state's future compliance in other issue areas? Meanwhile, does the domestic public believe their state's past compliance with a particular issue area will lead to more optimistic beliefs among foreign publics about the compliant state's future compliance in other issue areas? Overall, the discrepancy in first-order and second-order beliefs found in this study poses important questions to advance the literature on reputation costs.

In closing, by focusing on how the public evaluates the likelihood of future compliance based on past state behavior, the study elaborates on reputation as a possible reason for the public's post-ratification demand for compliance. At a time when activist organizations in the United States are increasingly demanding that their government better comply with existing international legal commitments, this study suggests that the US public's perceived reputation costs and issue-linkages may be a key component driving public support for compliance.