Marking the fiftieth anniversary of diocesan congresses (Епархиальные съезды) in 1917, the priest Aleksandr Smirnov characterised these bodies for limited diocesan self-government as an exceptionally positive phenomenon against the background of the ‘otherwise gloomy history’ of the Synodal Church.Footnote 1 Established as part of church educational reforms in 1867, through which the Synod tried to decentralise the management and financing of diocesan schools and seminaries by involving the clergy, the congresses became laboratories of conciliarity. While pointing to the possible misuses of elective principles and limitations on free speech, Smirnov believed that several generations of clergy had been educated in the practice of conciliarity through this initiative.

Gathered between 20 September and 6 October 1905 in Riga, the diocesan congress called itself a council (sobor), a move lauded in the Church Herald, a newspaper published by the St Petersburg Theological Academy. The portrayal of those gathering as champions of sobornost’ and the bold proposals for reform made this council stand out from other ecclesiastical congresses, pointing to the fact that there were various local and grassroots forms of the conciliar movement within the Russian Orthodox Church at the turn of the century. The notion of sobornost’ is used without translation because it embraces several concepts, none of which alone conveys the full spectrum of this theological neologism. The Russian adjective ‘sobornyi’ is used in the Nicaean Creed as one of the attributes of the Church (catholic or katholiki). The Greek term refers to catholicity in the sense of the universality of the Church, but in the Russian usage it acquires an additional meaning. ‘Sobornyi’ comes from the word ‘sobirat’, to be called for a meeting, to gather together. The noun ‘sobor’ in Russian means both a cathedral and council. Thus, sobornost’, a neologism coined by the Russian Slavophiles, incorporates the meanings of the catholicity, universality, oecumenicity or synodality of the Church. Paradoxically, the Slavophile philosopher Aleksey Khomiakov, the acknowledged father of the term, did not use it as a noun. Since Khomiakov wrote his treatises in French, it is his translator Iurii Samarin who should be regarded as the inventor of sobornost’.Footnote 2 None the less, Khomiakov's understanding of the Church's catholicity as expressed through reaching consensus about truth in doctrine and church administration through the practice of conciliarity or synodality was a novel way of looking at ecclesiology in the nineteenth century: ‘Is it not to the Church, gathered together in its entirety, that understanding of the divine truths is given?’Footnote 3

A fuzzy theological concept, sobornost’ nevertheless gained currency in Russian Orthodox discourse from the 1860s to the end of the old regime and impacted upon the movement for church reform, since the ideal Church presented by Slavophile thinkers, that consisted of the ‘concord and unity of spirit and life of all her members’, did not correspond to the reality of the Synodal Church.Footnote 4 The currents within the conciliar movement in the Russian Church varied from minimalist to maximalist, from conservatives to populists, but most parties agreed on the need for a local council and ecclesiastical reforms.Footnote 5 The inclusion of all groups into the decision-making process was believed to be the way to achieve true sobornost’. It is possible that the adoption of the title sobor for the Riga council in 1905 was influenced by the dominant discussions on sobornost’ and the preparations for the All-Russia Council which were under way.

Scholars have approached congresses as a Synodal institution that outgrew their original corporate clerical character and became a ‘crucial arena for the expression of religious and also political ideas at the grassroot level’.Footnote 6 Gregory Freeze, for example, writes that the Holy Synod in 1905 gave a green light to extraordinary congresses and the involvement of the laity, noting the role of bishops and drawing attention to the cautious post-1905 attitude of the clergy to the ‘laicisation’ of a formerly clerical institution of self-government.Footnote 7 While Freeze emphasises the narrow corporate interests of clerical congresses, Daniel Scarborough believes that congresses were institutions for coordinating pastoral work beyond the boundaries of the clerical soslovie. These congresses became an integral part of clerical associations between the late 1860s and 1917 that advanced a culture of accountability and consciousness of social ministry while also facilitating mutual aid networks that helped not only the clergy but also their parishioners.Footnote 8

The representation and inclusion of various groups in collegial forms of ecclesiastical life were key themes in the so-called ‘conciliar movement’ between 1905 and August 1917, when the All-Russia Church Council took place.Footnote 9 During the revolutionary year of 1917, when the grassroots activities of the laity and clergy led to a number of extraordinary congresses that elected bishops, the question of church reform and the role of diocesan congresses were linked.Footnote 10 The remarkable activisation of the laity and the parish clergy in 1917 has been interpreted by scholars as a ‘church revolution’: one of its expressions was a clash between the bishops and the parish clergy. The spontaneous episcopal elections that took place at diocesan congresses in 1917 demonstrated the clergy's incredible ability for self-organisation and paved the way for the activisation of various church groups and communities, including women.Footnote 11

The issues discussed at the council were connected with the larger issues convulsing the Russian Orthodox Church during the last decades of the old regime. These challenges, which had their origin in the period of the Great Reforms (1860s–1870s), were rooted in the Church's institutional structure and deeply linked to the rapid modernisation of society and the economy. The first group of challenges concerned vociferous criticism of the Church from within and proposals for church reforms. Starting from publications in journals such as the Orthodox Review, the development of the debate led to the convocation of several commissions and consultations by the Synod with the support of the state, including a survey of bishops (1905) and the Pre-Conciliar Commission (1906–8) that aimed to prepare for the Local Church Council.Footnote 12 The central issues of the proposed reforms were the broadening of self-government in the Church, which would include parish reform and the reform of the higher church administration.Footnote 13

Secondly, problems concerning the corporate identity of the clergy continued to be discussed, despite the new legislation which made the boundaries of the clerical сословие (caste) more permeable. The material, educational and social characteristics of the clergy continued to define its status and image in society, while the impact of the clergy on other social groups remained limited.Footnote 14

Thirdly, difficulties in the parish school system loomed large in the late imperial period. While parish schools constituted a parallel to the local government (zemstvo) schools, in many ways they represented a complementary system of popular education. Since these schools received modest funding from the Synod and relied on the poorly paid labour of the clergy, including sacristans, this led to the haemorrhaging of qualified teachers from church schools, making them ineligible for grants from the Ministry of Education and less competitive. As such, they began to decline after 1906.Footnote 15 While the Synod wanted the church schools to counteract the influence of sectarians and non-Orthodox religions (including Roman Catholics and Lutherans) on peasants, the lack of qualified staff made this aim unachievable.Footnote 16

Fourthly, there was the Church's complex position in the imperial borderlands. The late imperial period was characterised by tension between the Orthodox Church's universalist orientation, which tended to override concerns about ethnic difference, and the state's policy of integrating the empire through language, education and the disempowering of local elites. The russification of schools and administration in the Baltic borderlands not only stirred protest on the part of the Baltic German elites, but also stimulated the rise of subaltern nationalist movements. Autonomist claims among the Orthodox in borderlands like Georgia were a response to rural unrest and the movement for reform in the Church.Footnote 17 The Baltic Orthodox dioceses, of course, differed from Georgian Orthodoxy in that they lacked any historical precedent for ecclesiastical autonomy, had a weaker connection to nationality and represented a minority rather than a majority. However, unlike the Finnish Orthodox, the Estonian and Latvian Orthodox had a broader social base among the local population, which also provided a significant proportion of candidates for the clergy and parish schoolteachers.Footnote 18

The significance of the Riga council in 1905 is that all the issues sending waves of turbulence across the Russian Church were openly and constructively discussed in an ecclesiastical event that took place on the Russian Orthodox Church's geographical periphery, thus making this event a precursor of future gatherings that took place only when the old regime had already been toppled. Paul Valliere perceives the ascent of conciliar ecclesiology as a frontier phenomenon: the creative ecclesiology of the Romanian metropolia of Transylvania and the Serbian metropolia of Karlowitz ‘existed on a frontier’ where Orthodox communities lived in a non-Orthodox state side-by-side with non-Orthodox neighbours.Footnote 19 The Russian Church faced a new frontier in the form of secularising forces and the end of its religious monopoly in the wake of officially granted toleration in 1905, similar, in Valliere's view, to the situation in which the Anglican Church found itself in the nineteenth century after Roman Catholic emancipation.Footnote 20 The religiously diverse regions of the Russian Empire, some of which had only recently been colonised, presented a challenge for the Orthodox Church in the late imperial era. On the one hand, church leaders responded by focusing on ‘positive knowledge’ and emphasising the pre-existing historical connections of the non-Orthodox regions to Orthodoxy, making these connections visible by building new churches and expanding diocesan infrastructure.Footnote 21 On the other, calling diocesan councils and accepting bold proposals, the Russian Orthodox leaders demonstrated a flexible and tolerant approach to the aspirations of the borderland Orthodox minority.

There is a connection between Orthodoxy's response to the religious toleration declared by Nicholas ii in 1905 and the activisation of collective forms of representation, including congresses.Footnote 22 Paradoxically, while the Orthodox Church mobilised various forms of conciliarism in response to religious toleration, it unwittingly imitated the practices of conciliarity already very much in use by the Old Believers.Footnote 23

Most studies that have discussed the Orthodox Church's march towards the Council of 1917 have focused on its top echelons, while regional and borderland case studies have only been used as illustrations. This article will focus on a borderland diocese where the Orthodox lived side by side with non-Orthodox neighbours and, despite Orthodoxy's status as the empire's established Church, lacked the de facto privileges associated with the state's predominant and pre-eminent confession.

Focusing on the role of the Orthodox council in Riga in 1905, it is argued that the church authorities were receptive to and encouraging of grassroots conciliarity even when it went beyond the norms deemed acceptable in other parts of the empire. The different outlook and background of the clergy in Riga diocese derived from the presence of men of Estonian and Latvian origin, who had been trained in Russian-speaking ecclesiastical seminaries and teachers’ colleges but served and preached in the local languages. These native representatives of the Orthodox Church to a large extent shaped the reform agenda, which was based on a vernacular understanding of conciliarity partly influenced by secular forms of mutual aid. In the imperial context, the role and influence of concepts and practices exported from the metropolitan Orthodox Church should not be discounted. While some of these concepts could be interpreted in different ways locally, this exchange was no doubt significant.

This article uses previously untapped sources: only two copies of the protocols of the Riga council have been preserved in Estonia. While the council ruled that 229 lithographical copies of the handwritten protocols should be made and sent to the parishes, it can be assumed that the actual number was lower.Footnote 24 While some rulings of the council were reported in the ecclesiastical press, historians thus far have had no access to the full proceedings of the event. In addition, this article relies on published documents to reconstruct borderland conciliarity in the diocese of Riga.

Background: Riga diocese and clerical congresses

While Riga diocese was established to counteract Old Belief, by the 1850s it had to cater for about 100,000 indigenous converts to Orthodoxy from the Estonian and Latvian peasantry. By 1914, the diocese had 273,023 parishioners organised into 267 parishes, 71 chapels and prayer houses, a seminary in Riga and 457 Orthodox schools with 18,227 students.Footnote 25

Originating in the era of the Great Reforms, Orthodox congresses assumed several functions, some of which were unintentional. Firstly, they became a legal outlet for a limited exercise in collegial administration in the dioceses, in addition to the consistory. In particular, they were responsible for the provision of diocesan educational institutions. In principle, the congresses could become organs for church reform, as the Riga council of 1905 clearly demonstrates. Secondly, the congresses performed some of the functions of an ecclesiastical court of law, dealing with violations of discipline and canon law by priests (for example, cases of extramarital relations). Thirdly, the congresses can be seen as institutions that manifested the corporate identity of the parish clergy and acted, in 1905 and after 1917, as representative institutions for all groups of the Church, including the laity.

While in the late 1860s priests in the Riga diocese regarded congresses as a waste of time and resources, especially in terms of travel expenses, eventually they found them to be important occasions for developing a common policy and a collective identity. During the 1870s, conciliar principles at regular congresses in Riga were developed according to the ‘majoritarian’ principle: the clergy received the agenda before the next congress so that all the clergy of the deanery could discuss the questions to be raised and authorise an elected delegate to represent them. If there was a majority vote for a policy which did not agree with the position taken by the deanery in question, the delegate had to join the majority, thus giving the congress's resolution a mandatory character.Footnote 26

Between 1867 and 1880, clerical congresses gathered annually in Riga diocese. After 1880, they began to be called semi-annually: between 1880 and 1903 there were thirteen congresses, while between 1903 and 1914 there were only five. An extraordinary congress was called in 1917; in 1919 a congress of all the parishes of the Estonian republic declared the formation of the new Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church. Prior to 1926, according to the statutes of All-Russia Local Church Council, diocesan congresses, to which representatives of each parish were called, were theoretically supposed to be held annually and functioned as the highest body of church administration. The statute of the Estonian Church of 1926 confirmed this rule, but, following a new statute in 1935, power shifted to the bishop.

The Riga council and the revolution of 1905

The revolution of 1905 began with Bloody Sunday, the suppression of a peaceful workers’ demonstration in St Petersburg on 9 January led by the Orthodox priest Georgii Gapon: for some contemporaries, this showed that the clergy had the potential to act as an arbiter between the authorities and the workers.Footnote 27 The Baltic province of Livland had the highest number of strikes per worker in the empire. On 16 October 1905 troops suppressed the workers’ demonstration in New Market square in Tallinn, which resulted in hundreds of victims and was called a ‘bloodbath’ by contemporaries. Following Tsar Nicholas ii's October Manifesto on 17 October 1905, which granted several democratic freedoms, numerous political meetings were organised and political parties formed. However, the end of 1905 saw an escalation of radicalisation that resulted in the rise of political radicalism, crime, boycotts of the tsarist officials and refusal to pay taxes. In the countryside, where the Orthodox Church had its main base, popular discontent turned against Baltic German landlords: in the course of a few months in 1905, 573 estates were ransacked and set aflame, causing damage estimated at around twelve million roubles.Footnote 28 In response to the violence, martial law was introduced on 24 December and the government sent in suppression squads, which relied on the active support of Baltic Germans, that executed 595 people and sentenced hundreds more to jail, forced labour and exile.Footnote 29 Altogether in the Baltic provinces, 2,652 people involved in revolutionary events were sent to Siberia.Footnote 30 Following the convening of the Duma, the first Russian parliament, in April 1906, the burning of estates and repression in the Baltic subsided. The central government allowed private schools to open which used the native language for tuition and it allowed teaching in native (Latvian, Estonian and German) languages in the first two years of elementary schools; workers’ conditions improved with the legalisation of a ten-hour working day and the universities received more autonomy.

In January 1905 Archbishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii, 1854–1928)Footnote 31 issued a circular letter to all parish priests in the Riga diocese, inviting them to advocate before the authorities for the arrested and accused participants in the revolution. Arguing that there was often no way to distinguish between the guilty and the innocent when courts martial were used, he called on the clergy to become mediators between the Estonian and Latvian populace, including Lutherans, and the authorities.Footnote 32 He established an aid committee for the families that had lost their breadwinners.Footnote 33 The archbishop's efforts were supported by the clergy and were gratefully received by local members of the public.Footnote 34

An escalation of violence in the Baltic took place in late autumn 1905, and the Orthodox Church took an active role in mediation in January and February 1906, that is after the Riga council, which took place in September 1905. Thus, the summoning of the council cannot be regarded as a response to the violence. In some ways, the Orthodox Church's response can be seen as a continuation of the course taken in spring 1905.

The unfolding revolution made possible the long-awaited expansion of religious toleration. The decree of 17 April 1905 legalised conversion from Orthodoxy to other Christian confessions and solved the problem of mixed marriages and their offspring. The total number of converts to Lutheranism between 1905 and 1915 was 20,116 men and women, peaking in 1905–6.Footnote 35

Following the routinisation of corporate clerical representation at congresses between 1880 and 1903, the diocese of Riga in 1905 witnessed the most extraordinary gathering of all representatives of the clergy, including indigenous clergy (both priests and sacristans) and laymen. Held on 20 September 1905, the Riga council (Rizhskii sobor) was the first to host delegates elected either by deanery assemblies or by brotherhoods. Afanasii Vasil'ev, a member of the Baltic Orthodox Brotherhood and author of a detailed report about the congress in the Church Herald, sang the praises of Agafangel: ‘God blessed Archbishop Agafangel with the good thought: to invite the lower members of the clergy and laymen to participate in the congress.’ ‘The first sign of reviving sobornost’’ was what he called this gathering in Riga. According to him, the Riga council was in the vanguard of church renewal. The presence of representatives of almost all of the Church, with the exception of monastics and women, was organised with episcopal permission. In response to the new era of religious toleration, Riga's diocesan authorities provided the Orthodox with an opportunity to address all grievances, complaints and suggestions from the parishes, brotherhoods and educational institutions.

Calling representatives from the parishes and brotherhoods to take part in the congress in 1905, Agafangel was not acting out of line. In other borderland dioceses with mixed confessional populations, such congresses were also called in the wake of the April manifesto on religious toleration. In the diocese of Polotsk, for example, Bishop Serafim (Meshcheriakov) called the clergy and laity to a diocesan congress in Vitebsk on 16–19 November 1905: this event played host to more than 100 priests and ‘many enlightened and pious laymen’. The author of the church chronicle of Ludzen parish in Vitebsk province commented that given the representative character of the delegates and the range of questions on the agenda, it was, due to the presence of the laity, the first true diocesan congress in the eparchy's history.Footnote 36

The composition of the council

The delegates of the council were a mixed bag. There were authoritative archpriests from cathedrals in Riga and Tartu, representatives of the Riga seminary, priests and psalmists from rural parishes and representatives of the brotherhoods. In contrast to the earlier clerical congresses, attended only by deans, priests made up just over half of all the delegates: the lower clergy (deacons and psalmists) constituted more than a third of the council, and the laity the remainder. Another feature that made this council different was that delegates of non-Russian origins constituted about 43 per cent. This corresponded to the growing proportion of Estonians and Latvians among the clergy (42 per cent according to the 1897 census). The Estonian and Latvian representatives were primarily psalmists. Russians dominated the lay people invited as representatives of the brotherhoods.

The clerical representatives were diverse. None of the members of the Riga consistory were elected, while the representatives of deaneries were parish priests rather than deans. Several Russian priests came with mandates from brotherhoods, not deaneries. The large number of Estonian and Latvian clergy in diocese of Riga was a result of the Riga seminary's recruitment policy, which, with some exceptions, stipulated that Estonian and Latvian boys should make up two-thirds of the student body. In some periods, this number was even higher. Between 1847 and 1884, the ratio of Estonian to Russian boys was 2:1, while in the era that followed Alexander iii's annulment of the status quo between the Baltic German elites and the tsar (1885–1905) (labelled by some as ‘russification’), the ratio was 7:1.Footnote 37 However, the Russian clergy attempted to challenge this legislation, and non-Russian delegates were seldom represented at diocesan congresses. At the 1871 diocesan congress, there was only one Estonian priest out of twelve delegates. This made native priests more inclined to promote the electoral principle, as this would increase their level of representation in the diocese.

Psalmists, many of whom were in their late twenties and early thirties, took an active role in the council. ‘There was at the council’, wrote Vasil'ev, ‘total freedom of opinion: a psalmist from an Estonian or Latvian parish fearlessly and passionately argued against not only an archpriest from a cathedral but sometimes against the archbishop himself.’Footnote 38 Psalmists (köster in Estonian, psalmotās in Latvian), often with an incomplete seminary or teacher's education, helped the priest at the altar, read, sang and taught in parish schools. Many psalmists were responsible for church choirs and contributed to the development of local Orthodox music.Footnote 39 Since the Orthodox parishioners of Riga diocese were in the main landless agricultural labourers unable to support parish priests, the government introduced a payroll (shtaty) for the clergy. The average annual salary of a priest was 1,300 roubles and for a psalmist 250–350 roubles, provided that they taught at the parish school.Footnote 40 Tensions between psalmists and priests were not exceptional before the 1917 revolution, an event in which the lower clergy took active part, calling themselves the ‘spiritual proletariat’.Footnote 41 Psalmists objected to the way in which priests tried to control school affairs and finances. Since Orthodox schools were less well-off than counterparts established by the Ministry of Education, psalmists with teaching credentials often left to find jobs in secular schools.Footnote 42 Even though clerical salaries in Riga diocese differed from the distribution of income in other parts of the Russian Orthodox Church, where priests received about 60 per cent of church income and psalmists only 20 per cent, it was clear that the position of psalmists in Riga diocese was not financially stable. This was why psalmists’ lower material status was brought up in the council of 1905.Footnote 43 The delegates tried to solve the problem by proposing the introduction of two positions for psalmists, one entirely concerned with the church and the other with the school.Footnote 44

Psalmists were actively involved in the discussion around clerical election at the council. The delegates criticised the figure of the powerful church dean, who ‘looks on his parish as his private fiefdom for his personal benefit’.Footnote 45 The delegates believed that elected priests would have a closer link with their parishes. It was possible that elections would allow popular psalmists to apply for priestly positions, while some parishioners might be able to obtain psalmist positions. The council ruled out this possibility, introducing an educational barrier: only those who had gone through at least five years in the spiritual seminary, or graduates of the teaching seminary could apply to be a psalmist.

The lay representatives at the council were primarily members of brotherhoods, which had been active in Riga diocese since the 1860s and 1870s. The brotherhoods consisted of representatives from the laity and clergy and were responsible for materially supporting and promoting Orthodoxy in the region. The representatives of two influential brotherhoods, the Baltic Orthodox Brotherhood (eight) and the Brotherhood of SS Peter and Paul (seven), came to the Riga council as delegates. It remains unclear why other brotherhoods, for example that of St Nicholas in Saaremaa, were not represented. While brotherhoods were idealised by some voices within the Church, others were sceptical, regarding brotherhoods as instruments of official Synodal policy.Footnote 46 In the imperial borderlands, where Orthodoxy was perceived as being besieged by a non-Orthodox majority, brotherhoods played an active role, sometimes acting without official permission from the authorities.Footnote 47 The lay members of brotherhoods in the council came from different social groups and professions: a merchant, a lawyer, state officials and teachers. Many of them were actively involved in brotherhoods, seeing them as civil associations that channelled their zeal for social mission and provided them with a society of like-minded people, connections to higher circles etc. For example, Petr Rutskii (1865–1926), a member of the Riga branch of the Brotherhood of SS Peter and Paul, was a teacher at the Alexander i high school in Dorpat (Tartu) and the author of handbooks, maps, guidebooks and teaching materials. Rutskii published the first handbook listing all civil organisations in Livland province in 1900, noting 1,241 organisations, including brotherhoods, which he placed among ‘miscellaneous societies’.Footnote 48 He argued that the tradition of civic organisation, originating in the Middle Ages, was based on the principle of mutual aid, which he characterised as a wonderful feature of these institutions.Footnote 49 He pointed out that the majority of peasant-based societies in Livland appeared only after the 1880s, which he credited to the emergence of Russian national self-consciousness and the ‘truly Russian school’ that accompanied the transfer of power from the ‘partial local nobility to the impartial government that takes care of everyone’.Footnote 50

Archbishop Agafangel and the council

Archbishop Agafangel (Preobrazhenskii), who has gone down in history as a possible successor to Patriarch Tikhon, but was prevented from filling this role by the Bolsheviks, was bishop of Riga from 1897 to 1910. The son of a priest and a talented graduate from the Moscow Theological Academy, he became a bishop after losing his wife in childbirth. Before his appointment to Riga, he served as rector in the Tobolsk and Irkutsk seminaries, as suffragan bishop of Irkutsk and as bishop of Tobolsk. Compared to his predecessor, Agafangel had a different approach to Riga diocese, with its majority Lutheran population, Baltic German elites disgruntled by the russification policies of the 1880s and a majority of priests of non-Russian origin. In contrast to Bishop Arsenii (Briantsev), he did not antagonise the Lutherans and Baltic German elites, but paid more attention to consolidating unity between different groups of clergy and the episcopal office. He encouraged the pastoral movement, the establishment of religious-pastoral societies, preaching in teetotaller tea houses and collegiality: he thus demonstrated his intention to be as egalitarian as was possible in the Synodal Church. He made concessions to the needs of the non-Russian Orthodox, financing the publication of two Orthodox periodicals in Latvian and Estonian. Agafangel's stance towards the Lutheran majority was unusual: he respected the local population's desire to maintain the faith of their forefathers while calling on Orthodox believers to show steadfastness, devotion and mutual love so they could serve as moral examples to the non-Orthodox.Footnote 51

Agafangel's convening of the Riga council in September of 1905 was an attempt to involve the entire diocese in reform, with the agenda formulated at local deanery gatherings and in the parishes and with delegates from the priesthood elected at a grassroots level. Agafangel demonstrated his intention to allow free discussion during the congress and allowed the vice-chair of the council to be elected rather than appointed. During the discussions, he made efforts to explain his disagreement with the most radical proposals by appealing to canon law and common-sense arguments rather than using his right to veto without explanation.Footnote 52 The archbishop's responsibility was to seek the Synod's approval of the council's resolutions and the proposed model of diocesan management, but this approval was not forthcoming.

It was not a coincidence that the special consultation (Особое совещание), established in 1907 in order to regulate the status of the parish, had Bishop Sergii (Stragorodskii) of Finland as its chair: he was later replaced by Agafangel. Both bishops were instrumental in bringing projects of parish reform based on their respective dioceses to the discussion table. Yet, the final result was far from the expectations of the Riga delegates or the project developed at the ad hoc Preconciliar Commission.Footnote 53

The rhetoric of sobornost’

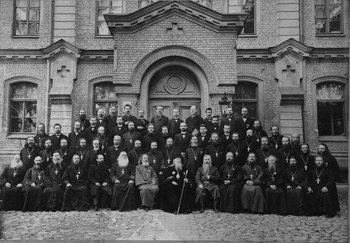

During the debate on parish reform, the delegate Afanasii Vasil'ev stated that the Church is sobornaia (Catholic in the sense of the Nicaean Creed): ‘The foundation of this sobornost’ can be found in the doctrine on the unity of the triune God, as well as in the human person, who consists of the mind, will and heart, the trinitarian unity of the basic elements of humanity, which can be considered human sobornost’.’ On the basis of the theology of the Trinity and the anthropological unity of mind, heart and will, Vasil'ev derived the essential sobornaia nature of the Church, represented as an organism (cf. 1Cor. xii.12–27). In addition, he appealed to apostolic times, when all decisions in the Church were made soborno, through councils.Footnote 54 In 1906 the Preconciliar Commission started its work in St Petersburg, while all diocesan bishops were invited to submit their reports on church reform in mid-1905. We do not know who influenced Agafangel and provided him with the materials for his report, but we can be sure that the Riga council was very important preparation. The notions of sobornost’ discussed at the council, especially during the session on parish reform, were vocalised by Vasil'ev. As a representative of the Baltic Orthodox Brotherhood, a public servant in the Ministry of Education and a controller in the Cabinet of Ministers, he was involved in the government's programme of railway construction. A son of a мещанин (unprivileged city dweller), he studied law at Moscow University in the 1870s. After years of service, he received the rank of state counsellor, which gave him the right to hereditary nobility. In his public life he was actively involved in the Pan-Slavist movement, setting up local branches of the Slavonic Committee, travelling to the Balkans and collecting donations to support poor Orthodox families in Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina.Footnote 55 In 1905 he founded a society called Sobornaia Rossiia, which was not very influential.Footnote 56 He published his Slavophile ideas widely and promoted a romantic, organic vision of the Church.Footnote 57 It is not clear how Vasil'ev got invited to the Riga council, but as he is sitting next to Agafangel in the group photo (see Figure 1 below), it can be assumed that he was a high-profile guest. However, since he was an outsider, his views cannot be taken to reflect the mindset of the local clergy and laity. In particular, there is no evidence to suggest that the word sobornost’ had any equivalent in Estonian or Latvian at the time. Yet, we cannot discard these ideas as being totally irrelevant for local Orthodoxy.

Figure 1. The congress of the Orthodox clergy in Riga, 1905. The photograph was taken on the last day of the council, when some delegates had already left. The photographer later glued in pictures of delegates who were not present. Photograph, from the private collection of Alexander Dormidontov.

The Riga council of 1905 had a blueprint in the writings of Archpriest Alexander Ivantsov-Platonov (1835–94), who published a series of articles on church reform in 1882 (reprinted as a book in 1898). Ivantsov-Platonov's views on the inclusion of the laity in diocesan congresses and his model of the relationship between bishops and their dioceses seem to have been replicated in the Riga council. The aim of semi-annual congresses, as Ivantsov-Platonov wrote, was ‘to give the bishop an opportunity to learn the opinions and needs of his flock and help him with the advice of the best people to manage the flock’.Footnote 58 The Riga council's discussion on elected bishops seems to follow Ivantsov-Platonov, who believed that locally elected bishops would maintain close contact with the faithful.

Towards a renewal of the Church

The questions discussed at the council were structured by the delegates quite broadly around the themes ‘Church’, ‘priesthood’, ‘church schools’, ‘the ecclesiastical press’, ‘land questions’ and, finally, ‘clerical mutual aid’. The range of issues concerning church self-government and the involvement of different groups in it occupied a substantial part of the discussion.

The delegates proposed a bottom-up reform of diocesan life, starting with the parish. The delegates critically reviewed the statute for the parish council and parish assembly that had been adopted – after fifteen years of deliberation – for the diocese of Finland. According to the Riga delegates, the first paragraph of this document, which limited the parish assembly's responsibilities to church property, had a stifling effect. Instead of the Finnish statute, the delegates suggested using the 1864 Statute on Parish Councils as a foundation while also broadening its social base. In contrast to the Finnish statute, the Riga council adopted a formula that expressed the rhetoric of renewal with regards to the most basic unit of church life, the parish: ‘all parish clergy together with all parishioners without exception should be recognised as one Christian commune, a little Church, an undivided part of the one body of Christ in which lives the spirit of Christ’.Footnote 59 Understood in this way, the parish community, incorporating all parishioners above twenty-one years of age, would participate in parish government through biannual assemblies, which would elect a council and control the budget.Footnote 60 The parish council, composed of members of the clergy and laity, would be chaired by either a priest or another member of the congregation as elected by the assembly. The members of the council were to be elected for three years and obliged to submit annual reports to the assembly.Footnote 61 Defining parish membership was not easy, since there was no parish tax in the Russian Church. In order to keep track of membership, the parish council should work out a form which each parish member had to complete, giving their personal data and indicating where they confessed.Footnote 62 While parish reform had been on the agenda of the Russian Orthodox Church since the 1860s, the process was slow and cumbersome. Aware of the slow-turning wheels of Synodal bureaucracy, the Riga delegates ruled that the Synod should approve the parish statute for Riga diocese on the basis of their proposal without waiting for a general decision for the entire Russian Church. The delegates argued that parish reform was especially relevant in 1905, since Orthodox parishes were in an unfavourable position compared to sectarian and Old Believer communities, which had received juridical and property rights.

Addressing issues like priestly and deanery elections, breaking up Riga diocese into smaller ecclesiastical units, and setting up a structure for the conciliar administration of church affairs, the delegates forwarded proposals for the renewal of church life, as expressed in the press around this time. Clerical election was not an issue that had the overwhelming support of the Russian public, as the materials of the Special Consultation suggest.Footnote 63 Yet, in the Baltic provinces this issue was regarded as central for the renewal of church life and strengthening Orthodoxy in the face of competition from ‘sectarian’ communities, which provided their members with more room for participation in religious life. According to Vasil'ev, it was the delegates from the Estonian and Latvian clergy who argued that elections would strengthen the moral bond between the priest and his parishioners and ignite popular interest in taking care of the church and in matters of faith.Footnote 64

Clerical election was the only issue during the council that was decided by secret ballot: out of sixty delegates, fifty-six voted in favour. Despite this overwhelming result, the bishop made it clear that, according to church canons, the parish could only have the right to nominate candidates for approval by the bishop.Footnote 65 The bishop's veto on this issue appeared to be decisive for reaching a consensus. Agafangel, who presided over this session, offered a compromise: the parish would nominate a candidate, the clergy (klir) would make a recommendation and the bishop would make the appointment. The candidates had to have a theological education and the approval of all the clergy of the deanery.

Clerical elections had been practised spontaneously during the nineteenth century. In the 1870s the parishioners of Tuhulaane parish in Viljandi deanery filed complaints against their parish priest Stefan Bezhanitskii, proposing another priest instead. Having been bombarded by letters signed by parishioners, who accused Fr Stefan of being a drunk, the dean allowed elections in May 1873, during which 192 votes were cast in favour of Bezhanitskii and fifteen votes against (in a parish with 1,082 male parishioners). Despite the favourable vote, Bezhanitskii was replaced a year later with a priest of Estonian stock, Fr Efim Küppar.Footnote 66 This case demonstrates that ad hoc elections were not an unfamiliar practice in Riga diocese: they were often carried out by deans to legitimise priestly authority by popular vote.

Other reforms discussed in the council included the liturgy and a broad spectrum of charitable and mutual aid activities. Communal participation in the Orthodox liturgy included congregational singing, communal confession and innovations that made the Orthodox service easier for people to comprehend and participate in, such as reading the Gospel facing the flock rather than the altar. Despite its affinity with Lutheran choral singing (without an organ), congregational singing was widely practised in Latvian and Estonian parishes, although it had not received official approval.Footnote 67 The council of 1905 approved the publication of congregational church music in local languages, thus encouraging the development of what one priest called ‘a united spirit’.Footnote 68 This form of parishioner involvement in the liturgy was already being encouraged by priests and sacristans, especially those of Estonian stock.Footnote 69

Estonian and Latvian clergy and psalmists were in favour of the liturgical reforms: many of the suggested practices had already been introduced in the nineteenth century but had met resistance from the consistory.Footnote 70 At the turn of the twentieth century, debates about congregational singing and rhyme verses during the liturgy were raging in the diocesan press.Footnote 71

The outcome of the council

The church reform movement in 1905 stalled: the hopes for an all-Russia church council in the near future did not materialise and many proposals made by bishops and priests were shelved. In Riga diocese, the council of 1905 was the first and the last representative body, at least before 1917, that included different groups within the Church. The Riga congresses of 1908, 1910 and 1914 consisted of only between eighteen and twenty delegates, primarily unelected representatives from each deanery. Even though the congresses referred to the rulings of the 1905 council, the implementation of some crucial decisions, such as parish reform, depended on the central authorities, while some other rulings were treated as ‘wishful thinking’ that could not be implemented due to the lack of financial support. The proposals concerning parish and diocesan reforms could not be carried out without the approval of the Holy Synod, which was never given.Footnote 72 Among the proposals implemented were the publication of local ecclesiastical journals and literature, and reforms concerning schools, including German-language tuition and the compilation of religious textbooks.

The council's proceedings were not published, even though both the Riga Diocesan News and the Church Herald reported the discussions in detail. The status of the council of 1905 in the history of Riga diocese remains unclear: on the one hand, future congresses referred to some of the decisions made in 1905, for example those concerning the teaching of German in Orthodox schools and spiritual journals. On the other, however, the major reforms were not mentioned in subsequent discussions.

While historians have focused on the failure of the Riga council to implement its resolutions, little attention has been paid to the decision-making there.Footnote 73 While it has been correctly pointed out that the council pre-empted the historic All-Russia Church Council of 1917–18, its inner dynamics still remain obscure. Despite the bishop's veto and the moderate line that prevailed, we need to evaluate the decision-making on the basis of its congruence with the principles that the council itself established: synodality and collegiality. The delegates often articulated polar positions, with Agafangel trying to hold the middle course between the maximalists and the moderates.Footnote 74 The maximalist position included more rights to parish members, the expansion of the electoral principle to all levels of the Church (including that of the bishop), the modernisation of the liturgy and other practices, and more room for local languages in education and services. The minimalists insisted on traditional forms of hierarchical authority, with some concessions to popular participation in church government with the permission of the hierarch.

The ability of the clergy to influence the council's agenda, to express their positions, to listen to opponents, to debate and to come to a consensus was an empowering moment for the Orthodox in Riga diocese. The collective portrait taken on one of the last days of the assembly reflected the spirit of conciliarity that the members exhibited. While there are no personal memoirs of the council, it can be assumed that the delegates had a chance to talk, exchange opinions, eat, socialise and pray with each other over these two weeks. These informal activities and relationships may have also strengthened the spirit of conciliarity and solidarity among different groups and individuals.

While the council of 1905 did not manage to implement more egalitarian principles, this did happen in 1917. The local diocesan congresses that gathered all over Russia demonstrated a high level of lay engagement and participation. The range of issues and political engagement at these assemblies differed from region to region due to geographical and local factors.Footnote 75 While the election of bishops and delegates to the All-Church Council in Moscow were features that they had in common, many factors made each diocese act in a unique way.

‘There is nothing mysterious about a church council’, writes Norman Tanner: ‘basically it is just Christians coming together to discuss matters important to them.’Footnote 76 However, in the Synodal era, the way for Russian Orthodox Christians to come together to discuss matters important to them was full of roadblocks. While some commentators in the last years of the old regime saw in diocesan congresses a hidden resource for conciliar revival, which they termed ‘a revival of sobornost’’, congresses had many limitations. First, they did not include all members of the Orthodox Church, such as lower clergy (deacons and sacristans), monastics and the laity. Women, especially, were not represented at these congresses. Secondly, the legal status of congresses was uncertain and their power was to a large extent limited by the diocesan bishop. Thirdly, the impact of congresses was also restricted. Rather than settling matters of faith, as the ecumenical councils of earlier eras did, the diocesan congresses dealt with matters of organisation, education, the liturgy and discipline.

The congresses in Riga diocese before and after 1905 also reflected these limitations. They served to defend the corporate interests of the clergy and strengthen confessional identity in the face of challenges from the multi-confessional environment and laws on religious toleration. The main focus of the Baltic Orthodox congresses between 1863 and 1917 was strengthening the position of the Orthodox Church in the region. However, in the early twentieth century there was a shift from the self-serving concerns of the Orthodox clergy, often understood as the preservation of social privileges, to a broader understanding of the Church as a community including the priesthood, the lower clergy (who were often teachers) and lay people.

The council of 1905 stood apart from previous and subsequent congresses in Riga diocese. In 1905 the diocese of Riga was in the avant-garde of the renewal movement thanks to two factors: the activities of Archbishop Agafangel and the predominance of indigenous clergy. The representatives of the Estonian and Latvian clergy, teachers and laymen developed an understanding of the Church more aligned with the idea of sobornost’ and advocated an inclusive approach to the parish community and the structure of the Church in general. The form of this locally-based conciliarity seemed to be popular and widespread in Riga diocese, and it was later integrated into the administrative structures of the Estonian and Latvian Orthodox churches.

Historians have pointed out that the problem of self-identity was at the centre of the crisis which the Russian Orthodox Church faced at the turn of the century, when all aspects of ecclesial life (the local, national and universal) ‘elicited mixed sentiments and evaluations’ and were subject to competing evaluations.Footnote 77 With no agreement over the interpretation of the theological concept of sobornost’, it became one such contested field, which, despite the term's broad appeal and popularity, suggested that ‘Orthodox ecclesial thinking faced a major impasse’.Footnote 78 While the argument that the late imperial Russian Church was in crisis is undoubtedly correct, the presence of conflicting interpretations of ecclesial community and how power should be distributed does not necessarily mean that the Church was at an impasse. One lesson that can be learned from the story of conciliar practices in Riga diocese is that having different opinions was not an obstacle to conciliarity but a sign of vitality.

Solidarity at congresses was difficult to achieve, but perhaps this was not the point. The principle of unity in diversity often meant that decisions had to be worked through dialogue and negotiation. The councils in the Estonian Orthodox Church after 1917 demonstrate that, despite the lack of solidarity between the Russian and Estonian parts of the Church, some important decisions were pushed through: even troublesome minorities managed to get a relative degree of autonomy through conciliar procedures. The Riga council certainly shows that the western borderlands provided an environment that was more hospitable to conciliarity. The integration after 1917 of the conciliar principle into the Estonian Orthodox Church, the successor of Riga diocese, provides insight into what the life of the Russian Church might have been like if it had not been constrained by Soviet legislation. In Russia, various forms of conciliarity, such as parish and diocesan councils, were implemented to some degree in the 1920s. Yet, these regional councils were not regular and were under the surveillance of the secret police (VChK); by the 1930s, they were replaced by episcopal councils.

Taking all this into account, the Riga council of 1905 is a forgotten manifestation of the conciliar movement within the Russian Church. To some extent, the materials of the council provide evidence of the assimilation of the debates and theological thought on sobornost’ that can be traced to the Slavophiles. More significantly, however, the council testifies to ecclesiastical creativity, practical reason and an energetic collective will to implement reforms within the Church by the representatives of the parish clergy. The scope and programme of the reforms suggested by the Baltic delegates surpassed to an impressive extent the reform attempts that emerged at the grassroots during this period outside Moscow and St Petersburg.