To what extent did mate preferences change during the twentieth century in Western countries? How did these preferences evolve along with economic booms and busts, wars, the development of the welfare state, or the profound transformations of the family? Although simple, these questions have proven difficult to answer. Due to data limitations, the long-term trajectory of mate preferences is mostly unknown. Our knowledge of these preferences during the first half of the twentieth century largely relies on anecdotal evidence and, starting in the 1960s, on episodic surveys. As a consequence, the existence, direction, and timing of changes in mate preferences during the twentieth century remain elusive.

This article attempts to provide answers to these questions by focusing on the case of France. I build a new dataset that can be used to study the evolution of mate preferences throughout the twentieth century in France. To do so, I digitized all the 340,000 matrimonial ads published in France’s best-selling monthly magazine from 1928 to 1994. This magazine, called Le Chasseur Français, is the main and only provider of matrimonial ads that continuously published ads throughout the twentieth century in France. This exceptional longevity allows studying how the mate preferences expressed in the ads evolved over this period. The time span includes four episodes of particular interest, due to their link with marital outcomes: (1) the 1930s when the Great Depression hit France and unemployment rates surged, (2) the years right after WWII when demographic imbalances were witnessed and the wealth stock was at its lowest, (3) the three decades following WWII characterized by the expansion of the welfare state and exceptional economic conditions, and (4) the period starting in the late 1960s where the family underwent profound transformations as marriage and birth rates declined, divorce and cohabitation rates increased, and women increasingly participated in the labor market.

Using dictionary-based methods, I classified the 1,000 most common words used in the demand side of matrimonial ads into four main criteria: economic, personality, tastes/cultural, and physical. My principal finding is that mate preferences changed profoundly over the twentieth century for both women and men. The most striking observation is the collapse of economic criteria. These criteria used to be the most sought-after in a potential partner in the 1930s and were progressively replaced by personality criteria. In other words, non-material needs seem to have replaced material ones.

Regarding the timing of these changes, it appears that mate preferences exhibit significant inertia to episodes of unprecedented changes in the history of France. Mate preferences were roughly stable across the 1930s and the Great Depression, WWII and its consequences as well as the expansion of the Welfare State and the economic prosperity during the decades following WWII. I detect evidence of a structural break only in the late 1960s/early 1970s for both women and men, at a time of profound social change in French society. Additionally, this break appears to be more pronounced for women, suggesting that the transformations of this period had a stronger impact on women than on men.

As one of the most important forces behind partner selection is assortative mating, I also analyzed the evolution of matrimonial ads expressing a stated preference for similarity. I show that the preference for homogamy is not a new phenomenon. If anything, it was more often expressed in the matrimonial ads of the 1930s than in those written in the 1990s. More importantly, I find that consistently with the overall trends, the motives for assortative mating were less and less related to economic criteria, particularly after the 1960s.

The decline in the importance of economic criteria and its timing is most consistent with theories describing the profound changes affecting the family that occurred in Western countries in the late 1960s. At that time, marriage and birth rates started declining while divorce and cohabitation became commonplace. Analyzing these changes, several theories by economists (Becker Reference Becker1981), demographers (Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa Reference Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa1986; Van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987), and sociologists (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004) have argued that, towards the late 1960s, marriage was increasingly based on the notion of companionship and love, and that individuals increasingly sought partners with whom they could share intimacy rather than partners that could provide financial assistance. The trends observed in the matrimonial ads and their timings are consistent with this interpretation. This suggests that the drivers of mate preferences are to be sought out in the determinants of the transformations occurring in the late 1960s, such as the rising participation of women in the labor market, the legalization of birth control methods, and a shift in attitudes. These factors appear to be more correlated to the evolution of mate preferences than economic booms and busts, wars, and the development of the Welfare State, which may nonetheless have been a prerequisite for the changes occurring in the late 1960s/1970s.

Arguably, the main limitation of these results is that the data do not originate from a repeated representative survey of French society. Therefore, while there are good reasons to think that these ads are representative of the French matrimonial market, one may question whether trends on this market are representative of trends in French society as a whole and what role composition effects might have played throughout time. To provide evidence on the size of these effects, I exploit the information contained in the supply side of the matrimonial ads. I construct variables indicating the age, matrimonial status, location, explicit mention of marriage, presence of children, and socio-economic status of the individuals posting ads. Using this information, I then perform an Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition through the time of the evolution of the demand for economic criteria. Overall, I find that composition effects do exist but seem to play a minor role in explaining the trends. In the main specification, for women, I find that about 15 to 20 percent of the decline in the importance of economic criteria can be explained by composition effects and, for men, that composition effects are smaller and range from 10 to 15 percent in the latest years.

Another concern may be that individuals began to use more subtle means to seek economic resources in a potential partner, perhaps because of societal changes. I provide two pieces of evidence suggesting that this possibility is unlikely to explain the findings. First, since age is an obvious correlate of economic resources, I study the evolution of the desired age gap between ad writers and their ideal partners. I show that the age gap mostly remained stable throughout the century and, if anything, declined towards its end. Second, I analyze the information contained in the supply side of ads, which can be considered as a lower bound for mate preferences. In line with the results on demand, I show that individuals increasingly stressed their personalities and reduced the number of words related to economic criteria.

The results contribute to a growing literature studying who marries whom and the evolution of marital sorting in the long term. This literature has particularly focused on documenting the evolution of the degree of assortative mating (Mare Reference Mare1991; Fernández, Guner, and Knowles Reference Fernández, Guner and Knowles2005; Schwartz and Mare Reference Schwartz2005; Bouchet-Valat Reference Bouchet-Valat2014; Greenwood et al. Reference Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov and Santos2014, Reference Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov and Santos2016; Eika, Mogstad, and Zafar Reference Eika, Mogstad and Zafar2019), as well as its consequences on inequality (Fernández and Rogerson Reference Fernández and Richard2001; Breen and Salazar Reference Breen and Leire2011; Frémeaux and Lefranc Reference Frémeaux and Arnaud2020). As these studies observe couples once they are formed, this literature remains unclear on whether the trends are due to changes in preferences or changes in the characteristics of marriage markets (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn1998). I contribute to this literature by providing direct evidence on preferences and document two new empirical facts. First, the results suggest that the importance of economic criteria has strongly declined over the twentieth century, in line with the hypothesis of Becker (Reference Becker1981) and Coontz (Reference Coontz2005). Second, the results indicate that personality traits have become key elements in the study of marital behavior. This resonates with limited literature on this question (Lundberg Reference Lundberg2012; Dupuy and Galichon Reference Dupuy and Alfred2014), hindered by the scarcity of data on personality traits.

The results are also related to literature that has attempted to understand why individuals marry, divorce, or choose to cohabitate and how these choices react to specific historical events. This literature has highlighted the role of changing economic conditions (Autor, Dorn, and Hanson Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2019), biased sex ratios (Abramitzky, Delavande, and Vasconcelos Reference Abramitzky, Delavande and Vasconcelos2011), and the development of the welfare state (Persson Reference Persson2020). The profound transformations of the family in the late 1960s, such as the fall in marriage and fertility rates, the rise of cohabitation and divorce rates, have been well established in France (Frémeaux and Leturcq Reference Frémeaux and Marion2018) as in other Western countries (Lundberg and Pollak Reference Lundberg and Pollak2007; Stevenson and Wolfers Reference Stevenson and Justin2007; Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2014). The results of this paper suggest that these latter transformations were accompanied by a shift in mate preferences.

Finally, the methodology used in this paper pertains to a literature that has analyzed mate preferences before pairing (for instance, De Singly 1984 and Bergström Reference Bergström2018 in France; Waynforth and Dunbar Reference Waynforth and Dunbar1995; Fisman et al. Reference Fisman, Sethi Iyengar, Kamenica and Simonson2006; Hitsch, Hortaçsu, and Ariely Reference Hitsch, Ali and Dan2010 in the United States; Belot and Francesconi Reference Belot and Marco2013 in the United Kingdom; Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Duflo, Ghatak and Lafortune2013 in India). This literature has exploited data from matrimonial ads, online dating, speed dating, or specific surveys. To my knowledge, only one study has attempted to characterize the evolution of mate preferences across time in a Western country (Buss et al. Reference Buss, Shackelford, Kirkpatrick and Larsen2001 last updated by Boxer et al. Reference Boxer, Noonan and Whelan2015).Footnote 1 I contribute to this literature by studying the case of France and providing the first time series on the evolution of mate preferences. From a methodological standpoint, this paper is also the first to use matrimonial ads to answer this question and could be reproduced in other contexts.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The first year in the data used in this paper is 1928. At that time, France was emerging from the so-called “Années Folles” (Crazy Years), a period characterized by economic prosperity and a dynamic cultural and artistic scene (Schor Reference Schor2004). This period ended with the Great Depression, which hit France in 1931 and whose consequences lasted until 1939. Between 1929 and 1935, real GDP declined by about 20 percent, while the unemployment rate exploded from 2 percent in 1931 to almost 15 percent in 1932 (Sauvy Reference Sauvy1984).

The 1930s ended with WWII, which impacted France in terms of both demographics and economics. In terms of demographics, WWII led to a small yet significant shortage of men. It is estimated that the military death rate during WWII was about 1.5 percent (Lagrou Reference Lagrou, Audouin-Rouzeau, Becker and Rousso2002). While sizeable, this figure is far below that of WWI, during which about 1.3 million men died for a military death rate of 16 percent and which led to a biased sex ratio up until the late 1940s (Gay and Boehnke Reference Gay and Jörn2017). In terms of economic costs, on the other hand, WWII had a more severe impact than WWI. As a direct consequence of improved bombing technology, about two-thirds of the wealth stock is assumed to have been destroyed during WWII (against one-third during WWI). According to estimates, the capital stock/national income ratio, which stood at 3.5 in 1934, fell to about 1.2 in 1949 (Sauvy Reference Sauvy1984). As a consequence, private wealth reached its lowest point in the 1950s, as did inheritance flows, halving from more than 10 percent in the 1930s to less than 5 percent of national income in 1950 (Piketty Reference Piketty2011).

After WWII, France entered into a period of exceptional and rapid economic transformation that lasted about 30 years. During this period, called “Les Trente Glorieuses” (The Glorious Thirty), economic conditions were exceptionally good (Fourastié Reference Fourastié1979). The GDP growth rate was about 5 percent per year on average during the period 1945–1973 (see Figure A1>), and unemployment remained close to its natural rate. It was also in this period that the main features of the French welfare state were designed. In 1945, Social Security was created and established, among others, mandatory health and retirement insurance, which gradually became universal; in 1950, the minimum wage was introduced; and unemployment insurance was created in 1958. This period ended with the 1973 oil crisis and was followed by two decades of weaker economic growth rate and a pervasive unemployment rate.

Towards the end of the 1960s, the family underwent profound transformations. One of its most striking manifestations was the weakening of the marriage institution, as illustrated in Figure 1. Since the late 1920s, marriage rates were at about 8 percent. They had only fluctuated in the short term, slightly declining during the Great Depression of the 1930s and jumping right after WWII. At the end of the 1960s, marriage rates started permanently declining, halving in two decades from 8 to 4 percent in the 1990s. The declining marriage rates were accompanied by a rise in cohabitation rates and the banalization of divorce (Figure A2), facilitated by a series of reforms that transformed family law, such as the introduction of divorce by mutual consent in 1975 (see Frémeaux and Leturcq 2018 for a lengthier discussion).

Figure 1 EVOLUTION OF MARRIAGE RATES IN FRANCE

Note: The y-axis represents the marriage rates per 1,000 people.

Source: The data come from the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies.

The end of the 1960s also witnessed three important evolutions, often considered as the causes of the transformations of family. First, an unprecedented improvement in women’s economic conditions started (Figure A3). For most of the twentieth century, the share of jobs held by women had been roughly stable at about 35 percent. In the mid-1960s, a clear break occurred, and from that date, the share of jobs occupied by women kept increasing until 2010, reaching over 45 percent. Second, the legalization of contraceptive pills and abortion in respectively 1967 and 1975 made birth control methods easier to access, and birth rates dropped sharply (see Figure A4). Third, a shift in cultural values took place (Roussel Reference Roussel1989) as attitudes gradually evolved towards individualism and self-actualization.

Two other important phenomena to keep in mind throughout the twentieth century are the evolutions of income inequality and immigration that could both influence sorting on the marriage market. Regarding income inequality, it decreased sharply in the aftermath of WWII, remained mostly stable up until the early 1980s, and then started increasing again (Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret, and Piketty Reference Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret and Piketty2018). Regarding immigration, existing statistics show that the share of immigrants in the population ranged from 6 to 8 percent during the twentieth century (Figure A5) and increased significantly after the two world wars and the decolonization that took place during 1945–1962.

DATA

Source

The data consist of all the matrimonial ads published in the monthly French magazine Le Chasseur Français from 1928 to 1994.Footnote 2 This magazine originally focused on hunting and nature. It was founded in 1885 and is still in circulation today. Throughout this period, its publication was only interrupted during WWII. For most of the second half of the twentieth century, it was the best-selling monthly magazine in France, peaking at about 800,000 copies sold per month in the 1970s (see Figure B2). Besides its original focus on hunting and nature, this magazine was famous for its classified ads. About half of its space was devoted to them. There were ads on many different topics such as jobs, housing, items for sale, and, importantly for this study, marriage.

The marriage section was created in 1919 and operated until 2010. This exceptional time span made the magazine the only one in France to have continuously published matrimonial ads across the twentieth century and the main supplier of such ads (Martin Reference Martin1980; Garden Reference Garden1981; de Singly Reference de Singly1984).Footnote 3 The analysis is restricted to the 1928–1994 period for two reasons. First, the marriage section grew in size over the years and quickly became the main section of classified ads published in the magazine. The section was divided into two categories according to the sex of the advertiser in 1928. For this reason, the year 1928 is the starting point for the dataset. Second, up until 1994, the structure of the marriage section remained relatively unchanged. In 1994, the name of the section changed to “marriage and dating,” and the foreword, previously insisting on the fact that ads should be serious and for marriage purposes, was removed.Footnote 4 Therefore, 1994 is the last point of the data. Another advantage of choosing 1994 as the end date is that up until that year, there was very limited innovation on the matchmaking market. Dating websites, which have since taken over the matchmaking market, only started to appear in France in the late 1990s.Footnote 5

To publish a matrimonial ad, individuals had to send the magazine their ads with the money needed to publish it. Fees were charged per word with a minimum of 10 words (see Figure B3 for the evolution of the price), and there was no discount for repeated ads. The magazine stated that matrimonial ads would be published in the month following receipt. Throughout the century, the magazine never set any limits on the number of ads it could publish per month. Nor did it ever give any guidance on how ads should be written, with the exception of a prohibition on soliciting photographs.

When published, each matrimonial ad would be given a unique anonymous identifier at the monthly level. To answer a matrimonial ad, individuals would need to write to the journal indicating the month and identifier of the matrimonial ad. The magazine would then forward the letter to the ad writer.

Descriptive Statistics

The dataset contains 332,106 matrimonial ads from 1928 to 1994. In Figure 2, we observe that the number of matrimonial ads was relatively stable in the 1930s, at about 2,500 ads written per year by women and men. The magazine stopped being published during WWII, from 1939 to 1945. Publication resumed after the war, with a very low number of matrimonial ads. This number quickly went back to pre-war levels and gradually increased until 1980 when it started decreasing until the end of the period. In 1994, there were about 2,000 ads written per year by women and men.Footnote 6

Figure 2 EVOLUTION OF THE NUMBER OF MATRIMONIAL ADS

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the number of matrimonial ads published per year.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

Throughout the period, the proportion of ads from the two sexes remained relatively stable. There was an increase in the share of ads sent by women in the early 1930s, from 45 to 52 percent (see Figure B4). Thereafter, it remained stable before increasing to 55 percent after WWII and remaining at this level until the end of the century.

Advantages and Limitations of Using Matrimonial Ads to Identify Mate Preferences

The use of matrimonial ads to identify mate preferences is part of an approach that consists of analyzing preferences before pairing, alongside the analysis of online dating and speed dating.Footnote 7 Matrimonial ads have been used in numerous studies such as Harrison and Saeed (Reference Harrison and Laila1977) and Waynforth and Dunbar (Reference Waynforth and Dunbar1995) in psychology, Martin (Reference Martin1980) and Gaillard (Reference Gaillard2018) in history, de Singly (Reference de Singly1984) and Jagger (Reference Jagger1998) in sociology, and Dugar, Bhattacharya, and Reiley (Reference Dugar, Bhattacharya and Reiley2012) and Banerjee et al. (Reference Banerjee, Duflo, Ghatak and Lafortune2013) in economics.

The analysis of matrimonial ads has three main advantages. First, individuals are free to express their preferences and do not have to rate them within a fixed set of pre-defined categories that may omit or distort their initial preferences. For instance, information on personality traits in survey data remains rare and has only been collected recently (as indicated in Lundberg Reference Lundberg2012, p. 2 or Dupuy and Galichon 2014, p. 1274) while they are among the most expressed preferences in the matrimonial ads. Second, it corresponds to a real-life situation with actual consequences and costs instead of a hypothetical situation. Third, in comparison with other types of data, matrimonial ads have a longer historical dimension. Online dating and speed dating services only started to appear in the late 1990s, while survey data used to proxy mate preferences were scarce, if not non-existent, before the 1960s.

The main limitation of matrimonial ads is the possibility of a selection bias. The data are not designed to be a representative survey of society and instead come from the actions of individuals who choose to use these services. Therefore, it could be asked whether these individuals have specific preferences or characteristics that are not representative of society as a whole and how this evolves through time. Another source of concern relates to whether these matrimonial ads are successful and lead to the formation of households or remain unanswered. These points are discussed in the section on the external validity of the findings.

METHODS

The Structure of Matrimonial Ads

Matrimonial ads are usually characterized by a demand-side and a supply-side (Coupland Reference Coupland1996), and the ads published in the magazine studied in this article follow this structure (de Singly Reference de Singly1984). The supply side consists of describing oneself. The demand side consists of specifying what the ideal partner looks like. To illustrate this structure, the following sentence is an example of a matrimonial ad written by a woman and published in May 1955:

This matrimonial ad has three parts. The first one is the supply side (from “single” to “hair”). The woman describes herself and specifies her matrimonial status, age, job, and some physical attributes (height, corpulence, hair). The second part is a delimiter, in this case, “answer,” between supply and demand. The last part is the demand (from “man” to “situation”). She is looking for a man aged 40 to 45 years old, with a good economic situation.

Classifying Mate Preferences

An important challenge in the analysis of this dataset is to synthesize and extract the information it contains. Potentially every word could be used as an outcome variable, but the results of such an analysis would obviously be difficult to read. Therefore, to identify mate preferences, I use a dictionary-based approach classifying words into four criteria: economic, personality, taste/cultural, and physical. These four categories encompass the most widely studied criteria in the literature on mate preferences.Footnote 8

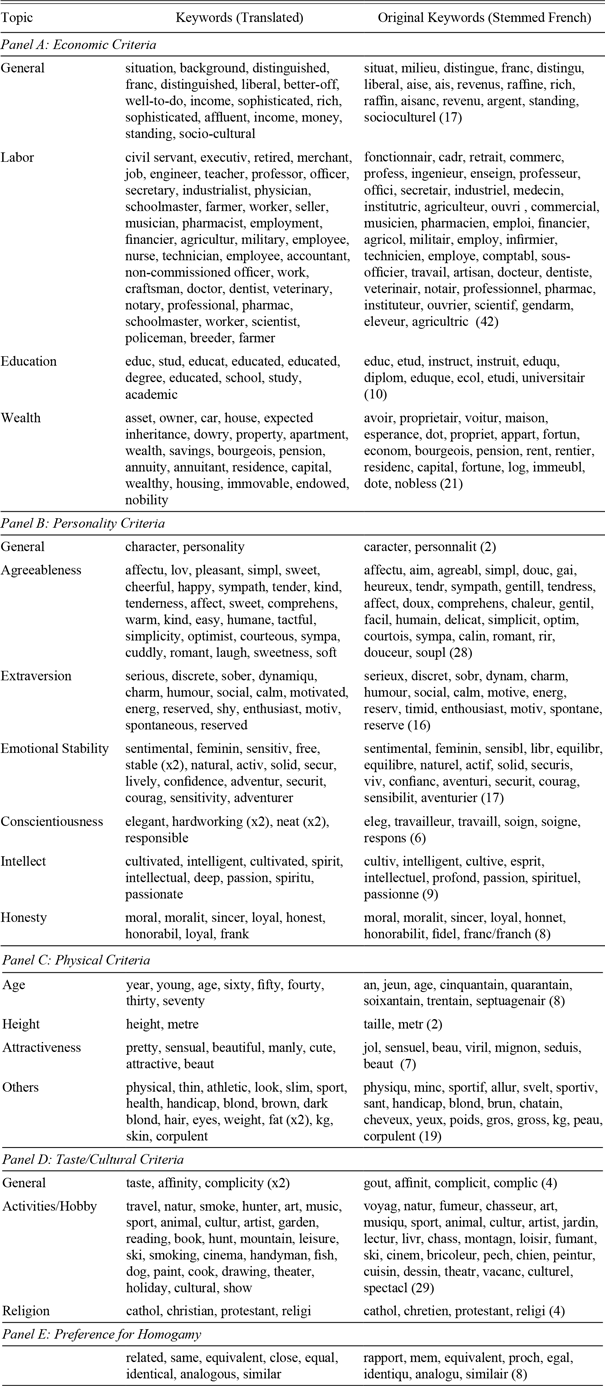

In practice, I computed a list of the 1,000 most recurrent words in the matrimonial ads. Then I manually classified each word into one of the four criteria and left out those that did not relate to any of them. As the publication price of a matrimonial ad directly depends on the number of words, a word-level classification seems to be more suited to the analysis than a classification of expressions or groups of words. Table 1 describes the complete list of words classified.

Table 1 LIST AND CONTENT OF DICTIONARIES USED TO CLASSIFY MATE PREFERENCES

Source: Author’s compilation.

Economic—The economic criteria best reflect material needs. To compute the list, I follow and update the classification of de Singly (Reference de Singly1984), who worked on a sample of matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français in 1978–1979. The sub-criteria are general, labor, wealth, and education.

Personality—To measure the demand for personality traits, I rely on existing works of psychologists who describe personalities using a limited set of categories (commonly referred to as the Big Five). They are often labeled extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect/imagination and are sometimes complemented with a sixth factor labeled honesty. To classify words into each of these categories, I follow Boies et al. (Reference Boies, Lee, Ashton, Pascal and Aadelheid2001), who developed a classification of the French lexicon into six categories and complement them with a general one for words that explicitly mention personality in a general sense (such as “personality” and “character”).

Tastes/Cultural—In addition to personality traits, individuals may seek partners with specific tastes, hobbies, and cultural preferences. This category encompasses the main activities an individual may do during his/her free time and religion. The sub-criteria are general, hobbies and religion.

Physical—Finally, the last set of characteristics relates to physical attributes. Along with economic criteria, they are the most discussed in the literature. The sub-criteria are age, height, attractiveness, and others. The inclusion of age as a physical criterion is discussed in the robustness analysis.

Unclassified Words—Out of the 1,000 most prevalent words, 249 were used to compute the four main criteria mentioned earlier. In Section C.2, I provide the complete list of unclassified words and descriptive statistics on their prevalence. Additionally, in the robustness analysis, I use different methods to classify part of these unclassified words and provide evidence that their non-classification does not affect the main findings.

Main Outcomes

The first set of outcomes corresponds to the overall evolution of the four main criteria described in the previous section. To do so, I compute the share of words related to each criterion in the demand side of matrimonial ads.

The second set of outcomes corresponds to the evolution of the preference for assortative mating with respect to each of these criteria. Since assortative mating reflects the tendency to meet similar individuals, I identify this preference using a dictionary including all the synonyms of the word “similar” within the 1,000 most common words (see Table 1 Panel E for the list and Section C.3 of the Appendix for the methodological details). In Appendix Figure D6, I also use an indirect measure of the preference for homogamy by comparing the supply and demand sides.

Population of Interest

Unless otherwise indicated, the analysis focuses on the demand side of matrimonial ads of individuals aged less than 40 years old. The main reason for primarily studying the demand side is that this paper focuses on preferences, and, by definition, these preferences are more likely to be found on the demand side. To disentangle the supply from the demand part of each matrimonial ad, I defined a list of 22 delimiters, following and updating de Singly (Reference de Singly1984), who studied ads published in Le Chasseur Français in 1978–79. This list is described in Table C4. It allowed me to split off about 96 percent of the matrimonial ads. The remaining 4 percent appear to be evenly spread over the century (see Figure C3) and consist mainly in unconventional ads in which there is no demand side or the structure differs.

Additionally, I restrict the sample to individuals aged less than 40 years old to approach the preferences of young individuals who are more likely to seek to form a family unit. The construction and validation of the age variable are discussed in Section C.5. Overall, I can correctly classify the age of an individual writing a matrimonial ad in 92 to 97 percent of cases.

The resulting sample contains 139,907 matrimonial ads. I discuss the characteristics of this sample in the section on the external validity of the findings and Section C.3. Moreover, to demonstrate the robustness of the results to the sample restrictions, I also study the evolution of the content of the supply side (in the Robustness Checks section) and replicate all the results on a sample including all ages (Section D.3).

MAIN RESULTS

In this section, I present the main results in light of the historical context. The theoretical implications for the determinants of mate preferences are discussed in the next section.

Overall Trends

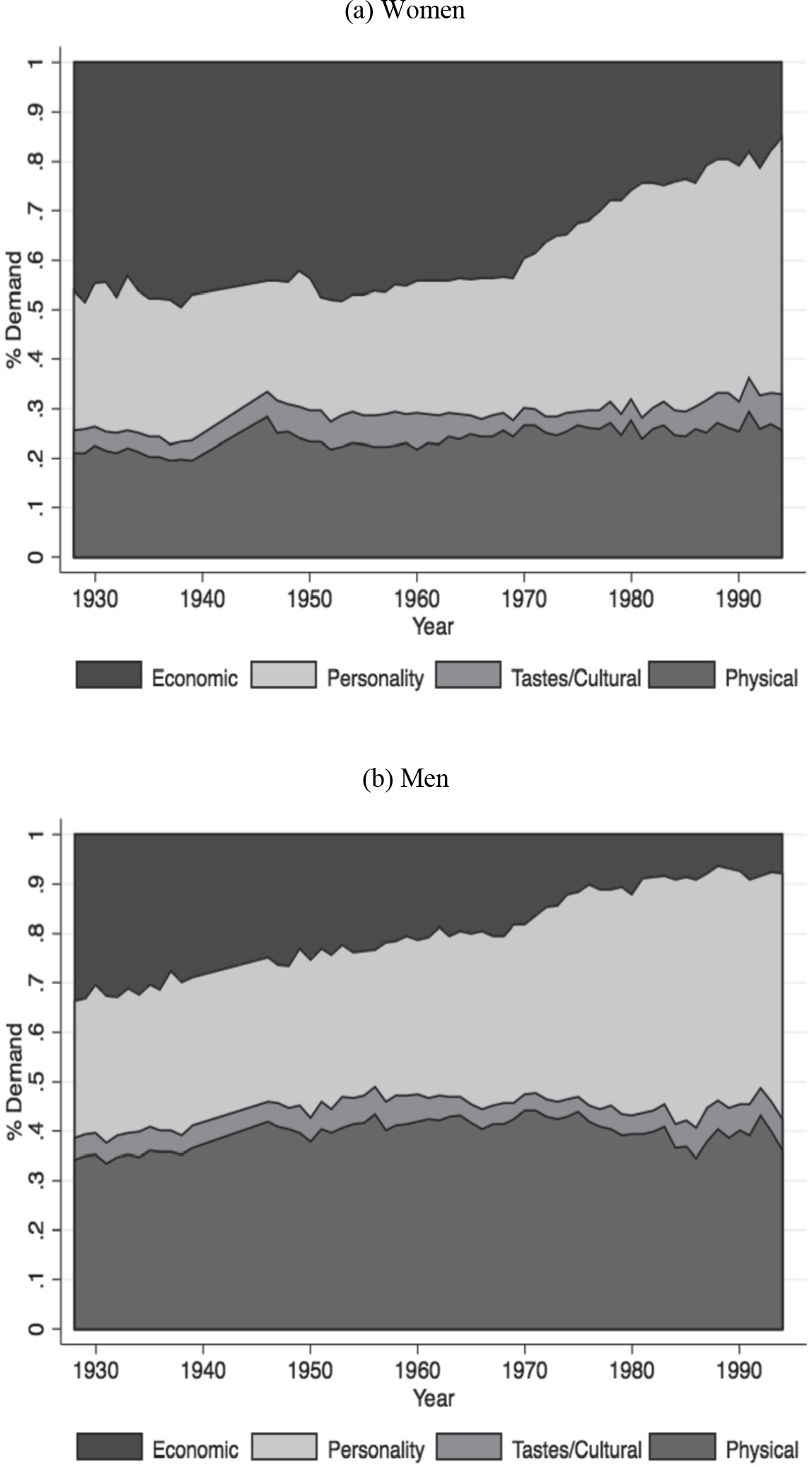

The first step of the analysis starts with the general evolution of mate preferences as regards the four main criteria. Figure 3 describes the changing nature of these preferences among both women and men. For each year in the sample, it depicts the respective share of the four criteria in the demand side of a matrimonial ad.

Figure 3 THE CHANGING NATURE OF MATE PREFERENCES

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of words related to each criterion in the demand side of matrimonial ads.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

Visually, it appears that most of the changes took place during the late 1960s/early 1970s. Before that period, despite historical events of unprecedented magnitude, the distribution of mate preferences across the four criteria seems to have remained almost stable, especially for women. Indeed, at the start of the period in 1928, economic criteria were the most important, averaging at respectively more than 40 percent for women and 30 percent for men. Personality and physical criteria came in second and third position and were about as prevalent, far more important than tastes and cultural preferences. We see that, despite the bad economic conditions of the 1930s, the distribution of preferences remained roughly stable during the entire decade. After this decade, the publication of matrimonial ads stopped during WWII and resumed in 1946. At that time, there was a demographic imbalance in favor of women, and the French economy was in a disastrous state. Yet, the mate preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads exhibit strong inertia and appear most similar to their pre-war distribution. The main noticeable difference is the temporary rise in the importance that women attached to physical criteria and the small decline in the importance of economic criteria for men. After WWII, a period of 20 to 30 years started, characterized by exceptional economic growth and the expansion of the Welfare State. However, again we see that the general distribution of preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads remained mostly stable for women. As for men, economic criteria declined slightly but continuously throughout the period (in the next section and in Figure D1, I show that this slight decline is attributable to the different demand for the wealth sub-criterion).

The main changes seem to have occurred around the late 1960s. Starting from this time, over a 10-year period, we observe more changes in the distribution of mate preferences than since 1928. During this period, for both women and men, economic criteria were progressively replaced by personality criteria. For women, the decline in the importance of economic criteria contrasts sharply with the stability that had prevailed since 1928. As for men, the changes are undeniable but less apparent, and a more fitting description would be an acceleration in decline in the demand for economic criteria. To confirm these visual impressions, I performed a Supremum Wald Test for a structural break with an unknown date on the demand of economic criteria for women and men separately.Footnote 9 The test statistics provide evidence of a structural break in April 1970 for women and July 1973 for men.

The strong importance of personality criteria in matrimonial ads at the end of the twentieth century resonates with a large literature in psychology showing that these criteria are essential to mate selection (Botwin, Buss, and Shackelford Reference Botwin, Buss and Shackelford1997) and influence relationship satisfaction (Malouff et al. Reference Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Schutte, Navjot and Rooke2010). Using different methods, more recent studies by economists have reached a similar conclusion and suggested that personality traits influence marital quality (Lundberg Reference Lundberg2012) and sorting on the marriage market (Dupuy and Galichon 2014).

Decomposing the Trends

To better understand the above findings, I decompose the evolution of each criterion through time. The purpose is twofold. First, mate preferences appear to exhibit significant inertia during episodes that are unprecedented in the history of France. This stability could be misleading and mask a reshuffling of the underlying components of each criterion. Second, this decomposition could also help explain a noticeable difference between women and men, which is the slight but continuous decline in the importance of economic criteria for men before the 1960s.

Economic Criteria—Figure 4 describes the evolution of the sub-criteria constituting the economic criterion. All the sub-criteria declined in importance throughout the twentieth century both, for women and men. Additionally, out of the four sub-criteria, over the entire period, women attach more importance than men to three of them: general, labor, and education. The only sub-criterion that men value more than women in their partner is Wealth. It is also the only sub-criterion that declined significantly before the 1960s.Footnote 10 To understand this earlier decline, Figure D2 goes one step further and presents the word-level evolution of the five most common words composing the wealth criterion (“dowry,” “asset,” “wealth,” “owner,” and “annuitant”). The prevalence of these words in the demand side of matrimonial ads was roughly stable during the 1930s. After WWII, there was a sharp fall in demand for dowries, which constituted the most sought-after wealth attribute in a woman, while the other sub-criteria seem to have gradually declined over the years that followed WWII. It is interesting to relate these patterns to those found in studies analyzing the role of wealth in the history of France throughout the twentieth century. Overall, wealth stocks and their transmission were at their highest before WWI and reached a minimum after WWII (Piketty Reference Piketty2011; Piketty and Zucman Reference Piketty and Gabriel2014; Frémeaux and Leturcq 2018). The gradual disappearance of wealth criteria from matrimonial ads could therefore reflect the aggregate shocks that the wealth stock suffered from in France at that time.

Figure 4 DECOMPOSING THE FALL OF THE DEMAND FOR ECONOMIC CRITERIA

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of words related to each sub-criterion of the economic criteria in the demand side of matrimonial ads.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

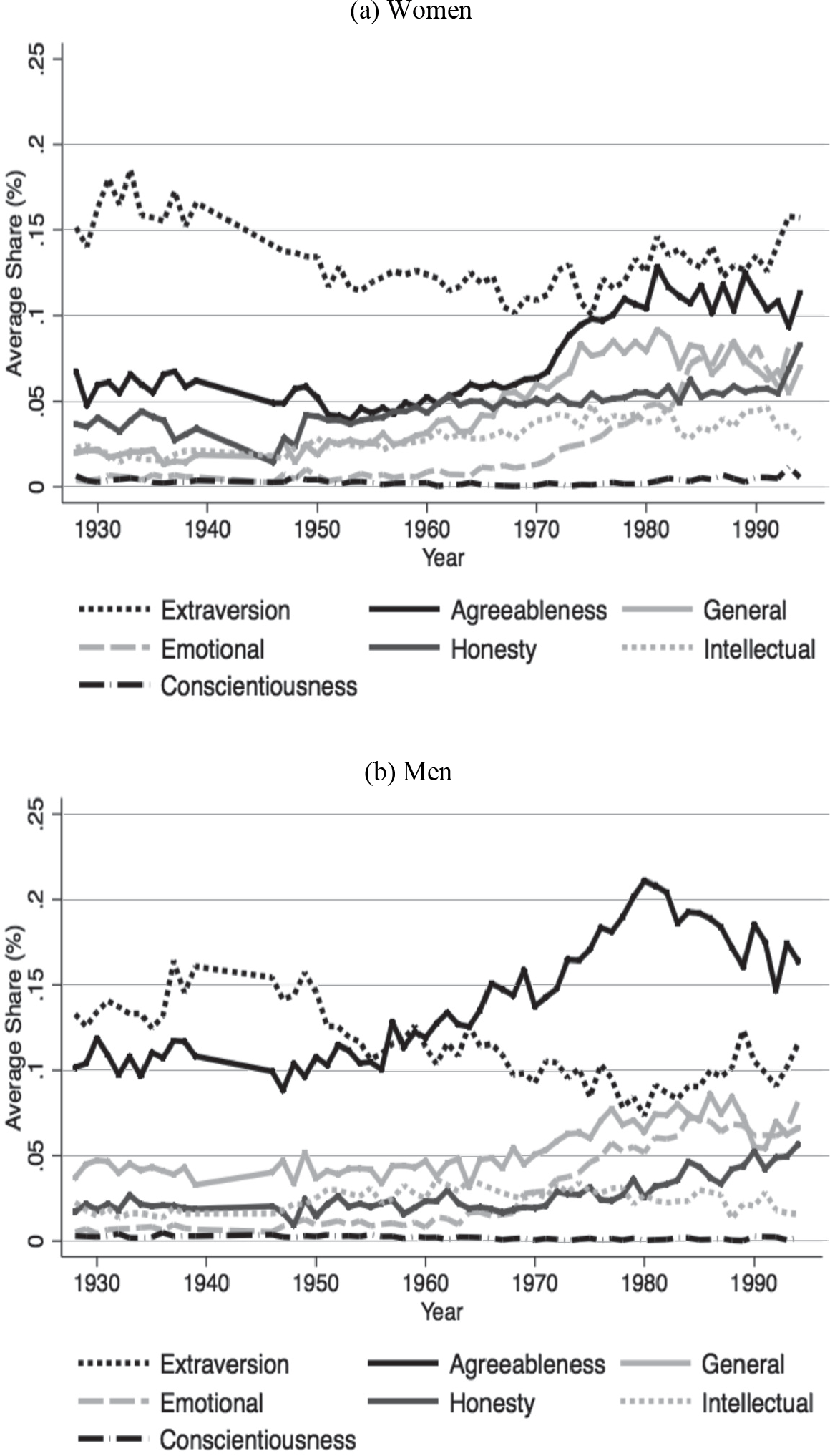

Personality Criteria—What explains the sharp rise in the importance of personality criteria? Figure 5 describes the evolution of the sub-components. First, we observe that for both sexes, the main sub-criteria that have increased are “Agreeableness,” “Emotional,” and the general one. Additionally, for women, these sub-criteria were remarkably stable throughout the 1930s and the Great Depression, WWII, and the reconstruction years. They exhibited a sharp rise only in the late 1960s. As for men, we also observe a sudden increase in the late 1960s, but also before that a gradual increase in the importance of Agreeableness and Emotional, replacing what used to be demanded in Wealth.

Figure 5 DECOMPOSING THE RISE OF THE DEMAND FOR PERSONALITY CRITERIA

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of words related to each sub-criterion of the personality criteria in the demand side of matrimonial ads.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

Physical and Tastes/Cultural Criteria—Are the two other criteria really stable? Or is this stability masking reshuffling effects? Regarding tastes/cultural criteria, we see in Figure D3 that this stability is misleading as it pools two contradictory effects: a disappearance of religious preferences and an increase in descriptions of hobbies/activities. The gradual disappearance of religious preferences from matrimonial ads in the early 1960s is consistent with the decline in religious practices in French society, which started at this period (Lambert Reference Lambert1993). As for indications of hobbies, one interpretation could be that they reflect the growing importance of non-material needs, and of finding a partner with whom one can share intimacy and have common interests.

Finally, the trends in physical criteria are displayed in Figure D4. We see that, despite a small increase in the importance attached to Height by women and Attractiveness by men, the overall trend appears to be stable in the long run. Yet, the short- and medium-term evolutions display interesting patterns and vary slightly along with historical events. In particular, after WWII, we observe a sudden jump in the share of words related to age criteria in the ads written by women. The demand for Age then went back to its long-run trend, while in the early 1960s, an increase in the share of words related to the height and the attractiveness of the ideal partner can be witnessed for women and men.

Implications for Assortative Mating

One of the important forces behind partner selection is assortative mating, which is the tendency among men and women to select partners similar to themselves. One may wonder whether the above findings also apply to the demand for assortative mating. If it does, we would observe a decline in the economic motive for assortative mating.

To answer this question, it is important to bear the French setting in mind. Contrary to the American context in which several studies have shown that marriages have been increasingly homogeneous through time (Schwartz and Mare 2005; Greenwood et al. Reference Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov and Santos2014; Eika, Mogstad, and Zafar Reference Eika, Mogstad and Zafar2019), the most recent estimates for France suggest the opposite. Measuring assortative mating on education and occupation, Bouchet-Valat (Reference Bouchet-Valat2014) shows that homophily is unambiguously an important factor explaining partner selection in France, but that its importance declined during the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 11 This decline is interpreted as the consequence of a slow unification of French society and the diminishing importance of social class (Bouchet-Valat Reference Bouchet-Valat2014).

To construct a measure of homophily, I quantify the evolution of words that reflect a preference for similarity in the demand side of matrimonial ads. It should be noted that this measure reflects a stated preference for homogamy rather than an observed one. If anything, it should be lower than that observed by relating couples’ characteristics because the latter is the product of several forces, including a preference for homogamy but also the marriage market characteristics (which usually reinforce assortative mating).

The results are displayed in Figure 6. I find that in the 1930s, about 30 percent of men and 20 percent of women were expressing a preference for homogamy. After WWII, the trends for women went up slightly, to 25–30 percent, and remained at this level up until the end of the period, while the share of men expressing a preference for homogamy gradually went down, from 25 percent in the late 1940s to 10 percent in the 1990s. Therefore, averaging across men and women, the preference for homogamy declined over time, which is consistent with what has been found on French data describing couples’ characteristics once unions are formed.

Figure 6 THE EVOLUTION OF THE PREFERENCE FOR HOMOGAMY

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of matrimonial ads expressing a preference for homogamy.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

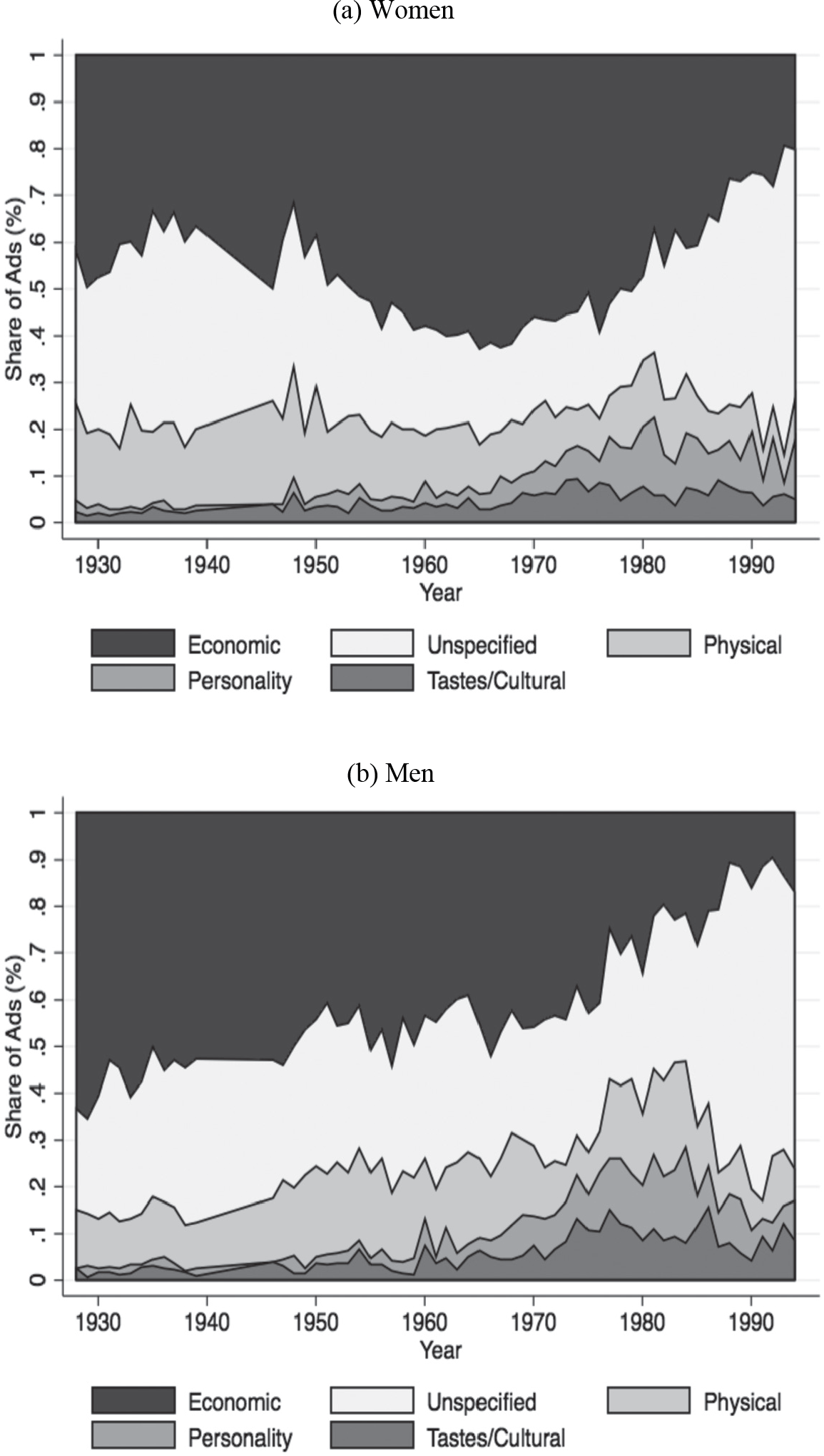

But what about the motives for assortative mating? How have they evolved? In the matrimonial ads, it is possible to decompose the evolution of the motives for homogamy by looking at the word associated with the preference for similarity. For instance, when individuals search for someone with a “similar situation,” the preference for homogamy is explicitly for an economic motive. I, therefore, classified all the words associated with the preference for homogamy using the four main criteria plus an “Unspecified” criterion when the word is unclassified or missing (see Section D.2 for the methodological details). Then I computed the evolution of the share of ads expressing one of the five motives.Footnote 12

Figure 7 describes the results. Over the long term, the economic motive sharply declined for both women and men, which is consistent with the previous findings. In the 1930s, the preference for homogamy expressed by women was in 50 percent of cases explicitly for the economic motive. For men, this share was slightly higher at about 60 percent. This distribution remained mostly stable throughout the 1930s, WWII, and the 1950s/1960s. It started to decline in the mid-1970s for women and slightly before for men. This decline was first offset by an increase in taste and personality motives. These two motives were practically never used in the early 1930s and averaged at about 10 percent for women and men in the 1990s. The decline in economic motives was also offset by a greater reliance on an unspecified motive. Ads classified under this category indicate that individuals are, for instance, simply looking for someone with a “similar profile.” Since the profile of an individual is described in the supply side of matrimonial ads, I also studied the content of the supply side when an “Unspecified” motive for homogamy is expressed (see Figure D5). We observe trends that are most consistent with the previous ones: economic criteria lost ground to personality ones, especially after the 1960s. This supports the interpretation that economic motives for homogamy declined throughout the century. Finally, the physical motive remained mostly stable through time and hinged almost entirely on demand for someone with a similar age (see Table D1).

Figure 7 THE CHANGING MOTIVES FOR HOMOGAMY

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of matrimonial ads expressing one of the motives for homogamy.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

It should also be noted that, although the patterns are similar in relative terms for both sexes, the story is slightly different in absolute terms as the overall preference for homogamy declined only among men. This suggests that the decline of the economic motive for homogamy has not been compensated by a rise in other motives for men. This result could reflect the fact that for motives that are not economic-related, men could have a higher tendency than women to prefer partners that are dissimilar. For instance, regarding the physical motive, men usually prefer younger partners, as noted in the literature on mate preferences (Buss Reference Buss1989).

DISCUSSION ON THE DETERMINANTS OF MATE PREFERENCES

The above findings show that the importance of economic criteria, both overall and among the motives for assortative mating, collapsed during the twentieth century. What led to these changes, and how can we interpret them? In this section, I attempt to provide answers to this question. I rely on the literature on the determinants of marital outcomes and discuss the role of these determinants in the historical context.

The first noticeable element is the relative stability of mate preferences during a large part of the twentieth century. From 1928 to the end of the 1960s, we observe very few changes in the distribution of mate preferences, although this period included the greatest economic crisis of the century, in the 1930s, and the strongest economic boom, during the decades following WWII. This seems inconsistent with the idea that changing economic conditions are the main drivers of mate preferences. It suggests that the impact of booms and busts on marital outcomes, studied in several papers (for instance, Schaller Reference Schaller2013; Autor, Dorn, and Hanson Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2019), may leave preferences unchanged.Footnote 13

The period from 1928 to the end of the 1960s also includes WWII, which devastated the economy and caused a demographic imbalance. Yet, as compared to pre-war levels, the main change in mate preferences is the sharp decrease in the demand for dowries by men, which could have been caused by the devastating impact of the war on wealth stocks. Besides this fact, mate preferences display only minor and temporary differences. This relative stability appears inconsistent with the argument that WWII brought a massive and permanent shock to mate preferences. One could argue that the demographic imbalance due to WWII was too small to alter mate preferences, but it should be kept in mind that the entire period from 1918 to 1950 was characterized by a biased sex ratio caused by WWI, which progressively vanished. In line with the interpretation of Abramitzky, Delavande, and Vasconcelos (Reference Abramitzky, Delavande and Vasconcelos2011), this stability suggests that biased sex ratios impact marital outcomes mainly through their impact on the characteristics of marriage markets.Footnote 14

Additionally, while income inequality is considered as a determinant of assortative mating (Fernández, Guner, and Knowles Reference Fernández, Guner and Knowles2005), there seems to be little evidence of a correlation through time between changes in income inequality and the evolution of mate preferences. Income inequality sharply decreased in the aftermath of WWII and seemed to have started increasing in the middle of the 1980s. Yet, these two periods do not coincide with the observed shift in mate preferences. Similarly, massive episodes of immigration after WWII could have directly changed the characteristics of the marriage market and influenced the preferences of the pre-existing society by bringing individuals with different cultures and different mate preferences. Yet, the timing of the evolutions of mate preferences does not correspond to the timing of major immigration waves.

Finally, starting at the end of the 1960s, we observe more changes in a 10-year period than in the previous 40 years. The changes are greater for women than for men but, for both sexes, it was the period where mate preferences changed the most. In French society, this period was characterized by profound changes in the formation and function of families (Roussel Reference Roussel1989). One of its most striking manifestations has been the important decline in marriage rates and the subsequent rise of cohabitation (As illustrated in Figure 1). It is interesting to note that the weakening of marriage can also be observed in the matrimonial ads. In Figure 8, I exploit the information contained in the delimiters between the supply and demand sides of matrimonial ads to plot the evolution of the share of ads that explicitly mention marriage.Footnote 15 We observe that the mention of marriage remained relatively stable up until the late 1960s, again suggesting that changing economic conditions and WWII did not permanently alter the perception of marriage. From the late 1960s onwards, the share of ads explicitly mentioning marriage started declining from 90 to 20 percent in the 1990s. This trend partly mirrors the evolution of marriage rates in French society after the 1960s, which suggests that individuals writing the ads are exposed to changes occurring in French society and may also have increasingly valued cohabitation.

Figure 8 EVOLUTION OF THE EXPLICIT MENTION OF MARRIAGE INSIDE MATRIMONIAL ADS

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of matrimonial ads explicitly mentioning marriage.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

The decline in marriage rates in the late 1960s, alongside the rise of cohabitation and divorce as well as the fall of fertility rates, has been observed at the same period in other Western societies. This set of transformations has led economists to argue that this period symbolized the end of the traditional family (Becker Reference Becker1981), while demographers described it using the concept of the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa Reference Lesthaeghe and Van de Kaa1986; Van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987) and sociologists advanced the idea of the “deinstitutionalization of marriage” (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004). At the heart of each of these theories lies the idea that mate preferences have moved from material to non-material needs, where individuals are increasingly looking for partners with whom they can share intimacy rather than partners than can provide financial assistance.

The empirical pattern in the preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads is consistent with such theories. They allow understanding of why mate preferences have shifted from economic to personality criteria. The key determinants of mate preferences are therefore likely to be found in the determinants identified by these theories as having triggered changes in the family in the late 1960s. These determinants usually include the empowerment of women, the legalization of birth control methods, and a shift in cultural values. In the French context, these determinants all experienced significant changes in the late 1960s, and it is difficult to identify which one may have started the process of changes in mate preferences, all the more so in that they are likely to be self-reinforcing.

The development of the Welfare State is also sometimes added to this list, and it should be emphasized that the French context does not rule out the fact that it may have been a prerequisite for the changes that occurred in the late 1960s. The timing simply suggests that it was not accompanied by a change in mate preferences in the short term. Similarly, while mate preferences do not seem to vary across economic booms and busts, we cannot rule out the possibility of a threshold effect whereby reaching a certain level of development may be necessary to observe changes in mate preferences.

EXTERNAL VALIDITY

Arguably, the main limitation of the above findings is that the dataset is not a repeated representative survey of French society. Individuals publishing matrimonial ads may have specific characteristics and preferences. More importantly, these individuals may change through time in a way that explains the changes in the preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads. I discuss this limitation in this section.

Can Matrimonial Ads Reflect the Preferences of French Society?

To provide evidence on the external validity, one might think of comparing a portion of the results to those obtained with an external dataset. However, to my knowledge, a survey of this kind with a historical dimension does not exist in France or any other country.Footnote 16 It is nonetheless possible to compare the results obtained at one point in time to some of the well-established stylized facts in the literature on mate preferences (for instance, the influential findings of Buss Reference Buss1989). This literature has shown that women seem to attribute more importance than men to economic criteria, and men seem to attach more value to physical criteria than women. Additionally, many studies find that men like having a younger partner more than women do. My analysis of matrimonial ads is consistent with these three facts.

Moreover, the main findings of this paper are on the variations through a time of the preferences expressed in matrimonial ads. Therefore, what is really important for external validity is that the preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads evolve in the same way as preferences in French society. Given the lack of data on mate preferences, it is difficult to quantify this potential bias. However, it should be noted that the popularity of the matrimonial ads market remained low but roughly stable through the twentieth century in France, suggesting that composition effects should be limited. The most accurate estimates indicate that, throughout the twentieth century, about 1 to 3 percent of marriages came through matrimonial ads (Bozon and Héran Reference Bozon and François1987). Additionally, the magazine studied in this paper is the only one that has continuously published matrimonial ads in France throughout the twentieth century and was widely considered to be the leader on the market of matrimonial ads (Martin Reference Martin1980; Garden Reference Garden1981; de Singly Reference de Singly1984). Finally, during the twentieth century, there was limited innovation on the matchmaking market, since online dating only emerged in the late 1990s. There, are therefore, good reasons to believe that the findings capture trends on the overall matrimonial ads market and that the relationship between this specific market and the French marriage market was stable.

Estimating Composition Effects

However, the previous points do not rule out the possibility of composition effects. In particular, it could be that a similar share of individuals found a partner using matrimonial ads but that their characteristics changed through time. If these characteristics were correlated with specific mate preferences, this could explain part of the evolution of the preferences expressed in the matrimonial ads. Note that changes in the characteristics of ad writers are the product of two channels: a changing pool of individuals using matrimonial ads within society and the changing structure of French society. For instance, since the structure of the French economy changed drastically, we should expect to find different jobs at the end of the century, as compared to the beginning. Therefore, changes in the characteristics of ad writers are likely to provide an upper bound of the “true” composition effects caused by the nature of the data and threatening external validity.

To provide evidence on the composition effects, I exploit the information in the supply side of the matrimonial ads to construct variables related to the characteristics of the individuals writing the ads: their age, location, matrimonial status, presence of children, job (I also study the role of education in the Appendix Section E.7) and explicit mention of marriage (using the delimiter between supply and demand).Footnote 17 This exercise certainly has limits because individuals are not forced to reveal information about themselves and may use the supply side strategically. For this reason, I considered that not disclosing a characteristic conveys information and therefore created a “missing value” category when a characteristic is missing (I relax this assumption in Section E.8).

Using these variables, I first show that the distribution of some characteristics, such as the location and the mention of children, have mostly remained stable through time (the descriptive statistics are displayed in Section E). On the other hand, the distribution of age, jobs, matrimonial status, and explicit mention of marriage seem to have changed through time.

How can these changes affect the results? To answer this question, I perform an Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Blinder Reference Blinder1973; Oaxaca Reference Oaxaca1973) through time using the first year in the data (1928) as a reference year, the demand for economic criteria as an outcome variable, and the set of variables presented above as explanatory variables. This method serves to decompose the trends in a part that can be explained by composition effects, quantifying how mate preferences have evolved only because of a change in the pool of ad writers, and structural effects, the part that is most likely to reflect a true change in preferences and shows how individuals with similar characteristics express different preferences at two points in time.

The results are displayed in Figure 9. Overall, the composition effects seem to explain a minor part of the findings. For women, the composition effects increase with time and seem to explain, towards the end of the period, 15 to 20 percent of the overall decline in the demand for economic criteria. In 1994, as compared to 1928 (the reference year), the demand for economic criteria had declined by a little less than 31 percentage points, out of which 6 points were due to composition effects. For men, the composition effects actually point towards an increase in the demand for economic criteria for most years and explain less than 15 percent of the decline in the latest years. The greater importance of composition effects in women’s ads could be due to the fact that changes in the 1960s affected them more than men. For instance, the female labor force participation rate started increasing markedly in the 1960s and, as a consequence, characteristics of women changed more than those of men.

Figure 9 OAXACA-BLINDER DECOMPOSITION THROUGH TIME OF THE FALL OF THE DEMAND FOR ECONOMIC CRITERIA

Notes: The y-axis corresponds to the average difference of the share of words related to economic criteria in the demand side of matrimonial ads between a given year and 1928. The black solid line corresponds to the sum of the composition effects and structural effects.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

Additionally, I also implemented a more flexible approach which consists of using the most common words as explanatory variables (Figure E16). I again find that composition effects, measured at the word level, play a minor role in explaining the findings (less than 10 percent).

A limitation of the decomposition is that it implicitly assumes that individuals who use the same set of words in different years are similar. This assumption could be violated if the connotation of some of the words changed throughout the century—in a way that they became used by individuals who have different unobservable characteristics and different mate preferences. This limitation is arguably difficult to test empirically. With the data at hand, a second-best strategy is to study the individual role of all the explanatory variables (age, location, matrimonial status, presence of children, explicit mention of marriage, job). The idea is that the more dimensions of the above variables that display a similar pattern, the less likely this limitation would be because it would imply that all the connotations of the words would have changed in a similar way. I study this question in Section E. For each dimension, I find that the demand for economic criteria followed a similar trajectory and substantially declined throughout the century for both women and men, and particularly after the 1960s. Therefore, while I cannot completely rule out the existence of composition effects explaining the results with the data at hand, the findings suggest that their impact is limited.

Over-Representation of Unsuccessful Ads

Another concern related to the external validity of the data could be that it over-represents the preferences of individuals that do not find a match. As unsuccessful individuals could repeatedly send matrimonial ads to the magazine, this could bias the results if these individuals have different preferences and if their proportion changed through time.

Given that the ads are anonymous, I computed an index of similarity for every two pairs of matrimonial ads within a given year and between two successive years. This index is based on the Jaccard similarity coefficient, which presents the advantage of being easy to interpret. A Jaccard coefficient above 0.8 indicates that two ads have more than 80 percent of words in common. To account for the fact that unsuccessful individuals may send different ads, I used different thresholds of similarity and compared the results with and without these similar ads. Figure E18 displays the results for different similarity levels (from 50 to 100 percent). The findings are almost indistinguishable with or without similar ads, suggesting that the over-representation of unsuccessful ads is unlikely to drive the results.

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

Alternative Interpretations

The interpretation of the results was that the demand for economic criteria collapsed. Another interpretation could be that individuals started using subtler ways to ask for them. In this section, I test the relevance of this alternative interpretation by reconsidering the classification of age and studying the supply side.

THE CLASSIFICATION OF AGE CRITERIA

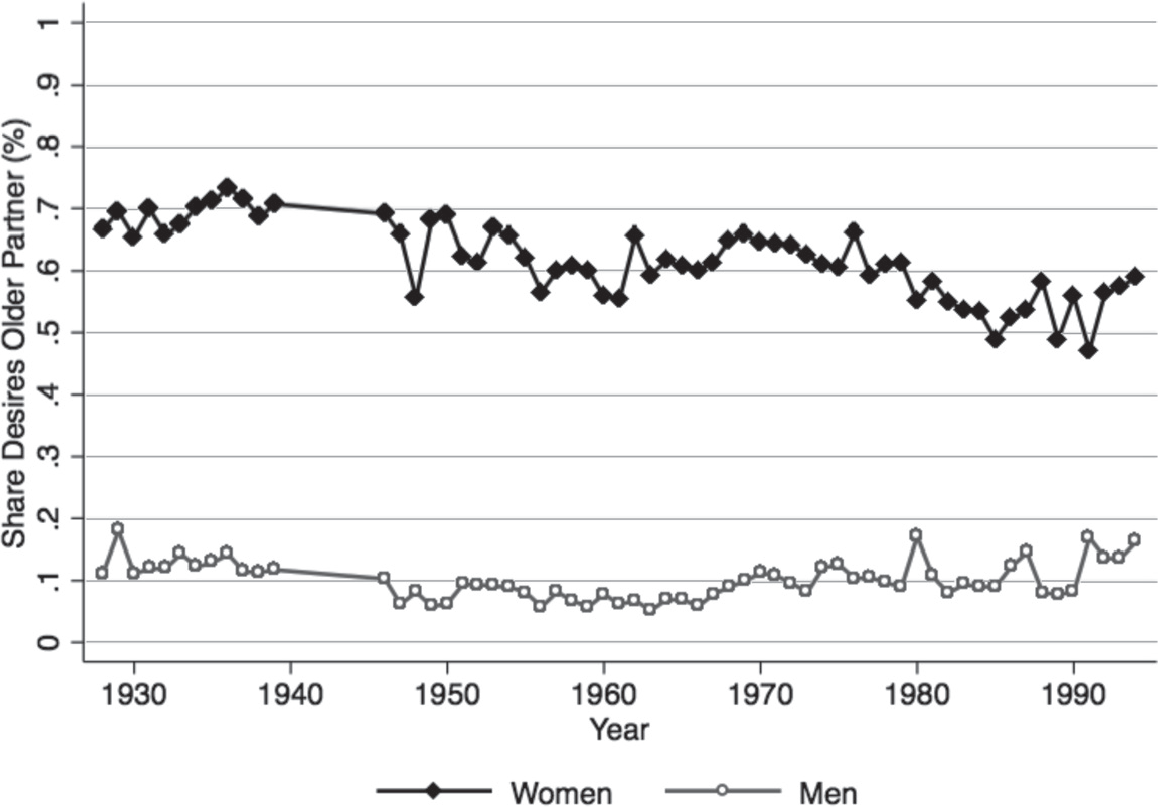

It could be asked whether age should be classified within physical or economic criteria. In the literature, searching for a younger partner is often interpreted as searching for a more attractive partner, while searching for an older partner is often considered as searching for a wealthier partner (see, for instance, Buss Reference Buss1989 or Mignot Reference Mignot2010 for France). To account for the ambiguity of age criteria, I directly study the evolution of the desired age gap throughout the century and also show how the results change when age is classified as an economic criterion.

To study the desired age gap, I constructed a variable indicating the preference for having an older partner (see methodological details in Section F). If individuals were replacing the demand for economic criteria with the demand for older partners, we would observe an increase in the share of individuals expressing a preference for older partners. Figure 10 shows that the preference for older partners has remained mostly stable through time. In the 1930s, about 70 percent of women and 10 percent of men were looking for a partner older than themselves. This preference remained stable throughout the 1930s. After WWII, we do observe some short-term movements for women, but it remains within the 60–70 percent range. By the mid-1970s, we observe an inflection in the curve whereby women started looking less for older men, reaching a minimum at about 50 percent in the early 1990s. For men, the preference is strikingly stable throughout the entire century. Therefore, desired age gaps tended to remain stable, and if anything, narrowed throughout the twentieth century, suggesting that individuals did not replace the preference for economic criteria with a preference for older (and wealthier) partners.

Figure 10 EVOLUTION OF THE PREFERENCE FOR HAVING AN OLDER PARTNER

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of ads expressing a preference for an older partner.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

To further demonstrate that the findings are robust to the classification of age as a physical criterion, I also computed the evolution of the demand for economic criteria (i) classifying age as an economic criterion and (ii) removing age from the classification. The trends are displayed in Figure F1. They show that the collapse of the demand for economic criteria is still observable, irrespective of how age is classified.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE SUPPLY SIDE

The main analysis focused on the demand side because it is arguably where we are most likely to observe preferences. However, the supply side could also convey information on mate preferences and provide a lower bound for their evolution. Indeed, the supply side contains both information that has to be mentioned, such as the age of the individual, and information that was mentioned strategically because other individuals might have a strong preference for it. For instance, at a time when economic criteria were greatly valued and sought-after, wealthy individuals may have devoted more space to describe their financial situation. Therefore, if the supply of economic criteria decreased, it would suggest that economic characteristics were deemed less important or less rewarding.

Figure 11 depicts the evolution of the way individuals described themselves. The patterns are mostly consistent with those observed on the demand side. Starting in the 1930s, we see that economic criteria occupied about 40 percent of the supply side for both women and men. This remained stable throughout the 1930s. After WWII, we see a small but temporary increase in the importance of economic criteria. Next, the distribution of preferences remained mostly similar throughout the 1950s and began to change in the late 1960s. At that time, personality criteria continuously increased in importance until the end of the period in the 1990s. This increase was stronger for women than for men and, at the end of the period, economic criteria were occupying respectively about 10 and 20 percent of the supply side of women and men.

Figure 11 THE CHANGING NATURE OF THE SUPPLY SIDE

Note: The y-axis corresponds to the share of words related to each criterion in the supply side of matrimonial ads.

Sources: The data come from all the matrimonial ads published in Le Chasseur Français between 1928 and 1994.

Alternative Methods

Finally, I present several robustness checks related to the methodological choices. I successively present results (i) using alternative measures of preferences, (ii) classifying adjectives and two-word phrases, and (iii) using alternative cutoffs to classify words.

Alternative Measures of Preferences—When presenting the main results related to the changing nature of mate preferences in Figure 3, the outcome consisted in the share of words attributed to each criterion. One may wonder how the results change using only a dummy or the raw count of words to measure the importance of a criterion. The results are displayed in Figures G1 and G2. Using these two alternative methods, the general interpretation is not altered as we observe a sharp fall in economic criteria and a rise in words relating to personality.

Classifying Adjectives and Two-Word Phrases—The classification was done at the word level, leaving aside two-word phrases and adjectives potentially related to words of interest. However, these expressions may reflect mate preferences. For instance, one may ask for a partner with a “good situation” instead of simply looking for someone with a “situation.” Alternatively, in French, some words become meaningful only when associated with another word, such as “housewife” (“femme d’intérieur” in French). If the use of such expressions changed over time, this could potentially alter the findings. To take this into account, I implemented two methods (see Section G2 for methodological details). First, I weighted all the words with the related adjectives using a syntactic dependency parser. Second, I manually classified the most common two-word phrases into the four main criteria. Figures G4 and G5 show that the results are robust to using these two methods.

Challenging the 1,000-Words Cutoff—For practical reasons, I classified only the top 1,000 words. One could ask how the choice of this cutoff impacted the results and whether the findings would be similar to alternative cutoffs. In Figure G6, I compute the importance of economic criteria in the demand side of matrimonial ads using the top 100, 300, 600, and 900 words. We see that the trends are essentially similar using the four cutoffs. This could be expected as word prevalence within texts usually follow a Zipf Law whereby the frequency of words falls more quickly than their rank in the total corpus.

CONCLUSION

During the twentieth century, France underwent profound economic, social, and demographic changes. In this paper, I studied how mate preferences evolved throughout these changes by using newly digitized data from all the matrimonial ads published in France’s best-selling monthly magazine over the 1928–1994 period. My main finding is that mate preferences changed profoundly. For both women and men, the search for economic criteria greatly declined and was progressively replaced by personality criteria. Similarly, I showed that the economic motive for assortative mating lost its importance over the twentieth century. The timing of these changes suggests that mate preferences were relatively stable during economic booms and busts as well as WWII. The bulk of the changes occurred in the late 1960s, at a time characterized by profound family transformations, an undeniable improvement in women’s economic conditions, a decline in birth rates, and a shift in cultural values towards individualism and self-actualization. Overall, these findings support theories arguing that, across the societal changes of the late 1960s, mate preferences increasingly expressed non-material needs at the expense of material ones.

Existing research on mate preferences has been limited by the lack of historical data on this question. This paper’s main innovation is to overcome this issue by using data on matrimonial ads. These data come with limitations, discussed in the paper, but also with certain advantages. In particular, matrimonial ads existed and were used in most countries before the emergence of online dating. It would, therefore, be interesting to study how mate preferences evolved through time in different historical contexts. In other Western countries, the late 1960s also coincided with profound societal changes that are comparable to those observed in France. Future research could therefore investigate whether, in these countries, mate preferences also shifted from material to non-material needs.