1. Introduction

Modern German differs from most other Germanic languages in that it has preserved the Proto-Germanic system with three grammatical genders (called masculine, feminine, neuter). In this paper, we explore the question of whether new ways of speaking (henceforth: the German multiethnolect) show any innovative deviations from Standard German that might suggest an ongoing restructuring or even simplification of this system, as has been reported for Dutch (Cornips Reference Cornips2008) and Danish (Quist Reference Quist2000, Reference Quist2008).Footnote 1 The German multiethnolect emerged in the 1980s and 1990s among second generation immigrants, mainly from a Turkish background. It is generally considered the most dynamic part of the German language today, and so it might be expected to spearhead developments that will eventually also spread to other varieties of German. We show that there is no evidence for such innovations, with the one (possible) exception of gender (and case) marking in the prenominal adjectival paradigm. However, we also show that restructuring in other parts of the multiethnolectal grammar leads to a reduction of grammatical contexts in which gender agreement is relevant.

We start out with a short overview of the gender system of Standard German and its acquisition by L1 and L2 learners, as it is sometimes claimed that L2 features might be the basis of multiethnolectal innovations (section 2). We then move on to discuss noncanonical gender assignment in determiners and the nonmarking of gender in bare nouns (section 3.1). We then analyze multiethnolectal innovations in the inflection of prenominal adjectives (section 3.2) and the emergence of a gender-neutral suffix for adjectival attribution. We conclude with a discussion of our findings and their interpretation (section 4).

2. Gender in German

2.1. The German Gender System

The German gender system provides a tidy threefold classification of German nouns, with only a very small number of ambiguous cases (often regional variants). As an inherent category of the noun, grammatical gender is relevant both for agreement within the noun phrase and for disambiguating anaphoric and cataphoric pronominal cross-references (see Murelli & Hoberg 2017 for a recent summary).

In the singular, German marks gender on the determiners and prenominal adjectives/participles as well as in certain appositional structures within the noun phrase (internally controlled gender agreement), and on personal, relative, and possessive pronouns outside the noun phrase (externally controlled gender agreement). In the plural, gender is neutralized in all contexts. Adjectives are only inflected in the attributive function, not as predicates (with exceptions in some dialects). Only 3rd singular pronouns are gender-marked; 1st and 2nd person pronouns show no gender distinction. Numerals apart from ein ‘one’ are no longer gender-marked (with traces of the older system surviving in some dialects). German does not mark gender in reflexive pronouns.

Let us first look at the NP-internal system of agreement as relevant for our analysis. Here the noun as the controller determines the morphology of the preceding determiners (definite, indefinite, demonstrative) and adjectives (including participles). In a noun phrase that contains either a determiner or an adjective (but not both), this element will receive gender marking. In a noun phrase that contains more than one possible target of gender agreement, the adjective may remain unmarked.

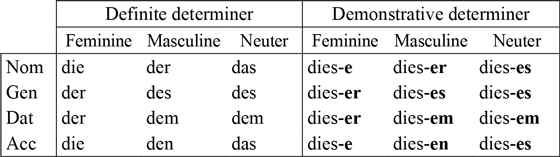

The system is most transparent in the case of definite and demonstrative determiners, whose gender forms interact with case as follows:

Table 1. Gender and case in the German singular paradigms of the definite and demonstrative determiner.

The indefinite and the remaining determiners (possessives, negative) use the same suffixes as the demonstrative determiner, with the exception of the nominative, where the masculine and neuter are zero-suffixed (as in kein ‘no’), and the accusative, where the neuter is zero-suffixed. As can be seen, there are numerous syncretisms. The forms of the neuter and masculine show more syncretisms with each other than with the feminine. Despite this fact, there is no tendency toward a two-gender system (as, for example, in the Romance pattern).

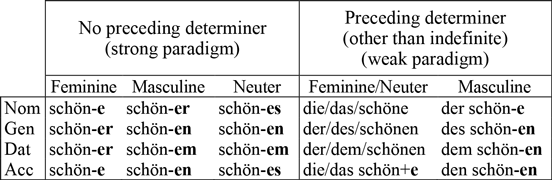

On the attributive adjective/participle, gender is morphologically marked in the most transparent way when there is no preceding determiner, that is, in the so-called strong inflection (shown for the adjective schön ‘nice’ in table 2, left-hand column). As the grammatical contexts in which a noun phrase with a prenominal adjective do not need a determiner are highly restricted, these forms are quite rare. In the much more frequent case of the adjective being preceded by a determiner (with the exception of the indefinite determiner), all suffixes are neutralized to -e (schwa) in the nominative or -en in the dative/genitive (so-called weak inflection; see right-hand column in table 2). A gender distinction between feminine/neuter and masculine is only made in the accusative. In table 2, the adjective schön ‘nice’ appears with and without a preceding determiner.

Table 2. Gender and case of German attributive adjectives (excluding the indefinite determiner).

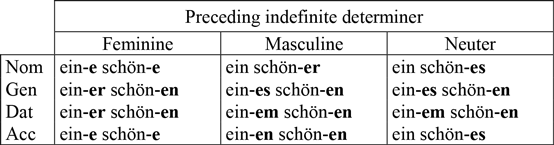

A mixed system is in place when an adjective/participle in a noun phrase is preceded by the indefinite determiner ein-, as shown in table 3. In this case, gender is overtly assigned in the nominative and accusative, but not in the dative and genitive (where -en is the gender- and case-unmarked suffix).

Table 3. Gender and case of German attributive adjectives (with the indefinite determiner).

We have outlined this rather complex system in detail to show that there are numerous positions in the paradigms in which gender (and case) are neutralized. In these cases, the suffix (-en or -e) marks the attributive function of the adjective only (as distinct from its predicative and adverbial functions). This is relevant for our discussion of the multiethnolectal structures found in the data.

Externally controlled gender assignment is somewhat more loosely organized, as natural and grammatical gender assignment may compete. Hence, phoric pronouns referring backward or forward to a neuter noun such as Mädchen ‘girl’ may be marked as neuter (grammatical gender agreement) or feminine (natural gender agreement). The most frequent phoric pronouns in spoken German are the so-called strong pronouns mostly identical in form with the definite determiners (der, die, das), and the weak (often cliticized) 3rd person pronouns (er/sie/es ‘he/she/it’).Footnote 2 The strong forms are also used as relative pronouns (der, die, das).

The only element of the German gender system in which slight indications of change can be observed is the possessive. In the possessive determiners, external and internal control apply simultaneously. They are gender-marked as required by the controlling noun within the noun phrase (possessum), and their stem is chosen according to the gender of the external controller (possessor), that is, sein (nonfeminine) and ihr (feminine). Hence, in a noun phrase such as ihr+en(ACC) Reiz ‘its/her charm’, the external controller determines the feminine stem (ihr), and the internal controller (the masculine noun Reiz) determines the suffix -en (accusative singular feminine). When the external controller is a feminine nonhuman possessor, there are weak tendencies to overgeneralize the nonfeminine stem sein- to feminine nouns even in the written standard language; therefore, one can find examples such as Abwechslung hat auch seinen Reiz ‘variety also has its charm’, instead of canonical Abwechslung hat auch ihren Reiz.Footnote 3 In this case, externally controlled gender is neutralized. It is interesting that this change affects a part of the gender system in which the tripartite gender distinction has already been reduced to the (Romance-type) two genders. As these inanimate possessive constructions are quite rare—and nonexistent in our data—the issue is not pursued here any further.

2.2. L2 Acquisition of the German Gender System.

Not surprisingly, the gender system as outlined above is a considerable challenge in the acquisition of German as a foreign language (see, among others, Christen Reference Christen, Diehl, Christen and Leuenberger2000, Krohn & Krohn 2008, Rieger Reference Rieger2011): As there is only little overt gender marking on the noun, gender of morphologically simple nouns needs to be learned for each word.Footnote 4 In addition, gender agreement interacts with case and shows a high degree of syncretism, which makes the system relatively opaque. Apart from difficulties in assigning German nouns to the three gender classes, existing research documents the overuse of e-inflection in prenominal adjectives (see, for example, Diehl et al. Reference Diehl, Helga and Irene1991, Dimroth Reference Dimroth and Ahrenholz2008:128): The suffix -e on the adjective (the nominative form of all genders) is generalized to the contexts requiring the strong inflection (Wegener Reference Wegener1995:108, Binanzer Reference Binanzer2017:78).

For the spontaneous acquisition of German as a second language by adults, omission of the determiner as well as overgeneralization of the (Standard German feminine) determiner die have been reported (Wegener Reference Wegener1995:108, Krohn & Krohn 2008:87). For bilingual children (German as L2 in sequential acquisition, L1=Turkish, Russian, or Polish), Ruberg (Reference Ruberg2015) found that the acquisition of the gender system follows the same pattern as in monolinguals, but lags behind considerably. In his study (based on an elicitation task), even monolingual children had not fully acquired the strong inflection of the adjective at the age of 5;0 (approximately 75% correct answers); the bilingual children (who were about a year older than the monolinguals and had been exposed to German for 30 months) achieved about 58% correct answers (for the respondents with Turkish as their L1, the number was even lower). However, Ruberg’s (Reference Ruberg2015) numbers do not distinguish between case and gender and are therefore somewhat difficult to interpret.

Finally, it is revealing to look at the spontaneous acquisition of German by first wave immigrants in the 1970s. In the so-called guest worker pidgin (an early fossilized learners’ variety of German), determiners are often lacking. Keim (Reference Keim1984:205) mentions that on average, an NP containing a determiner is used 26% of the time (including possessive determiners, which cannot be omitted for pragmatic reasons; the definite determiner would therefore appear to be used even less frequently); the same percentage is reported for NPs with an adjective, among which she includes numerals. The forms of the determiners ein/kein and the possessive determiners in Keim’s data often show “overgeneralization of the feminine form” (Reference Keim1984:205), that is, the e-suffix. Her examples suggest that the same applies to a considerable share of the prenominal adjectives (the examples in 1 are from Keim Reference Keim1984:207):Footnote 5

(1)

The utterance in 1a comes from a learner at a very elementary stage.Footnote 6 The same overgeneralization of the e-suffix in the adjective inflection is also attested in her data from linguistically more advanced “guest workers”, as in 1b. We return to this observation in the next section.

3. Gender Agreement in the German Multiethnolect

3.1. Data and Participants

In this paper, we look at multiethnolectal German as the variety of spoken German in which grammatical innovations are most likely to originate in the contemporary language, asking whether gender is affected by such innovations.Footnote 7 We use the term multiethnolect(al) here (following Clyne Reference Clyne2000, Quist Reference Quist2000), although we are aware of the terminological problems surrounding it and the criticism that has been raised against it (see, for instance, the discussion in Cheshire et al. Reference Cheshire, Jacomine and David2015, Cornips et al. Reference Cornips, Jürgen, Vincent, Nortier and Bente2015, and Jaspers Reference Jaspers2017). Some of this criticism is based on the claim that structural innovations that are generally assumed to have originated among speakers from immigrant backgrounds have started to spread to groups of speakers without migration background (de-ethnicization; see Wiese Reference Wiese2009, who argues that the former multiethnolect has turned into a general youth variety in certain urban neighborhoods). We do not deny such de-ethnicization; however, the empirical focus of our paper is on young people who live in multiethnic networks and come from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, and for whose way of speaking the term multiethnolect seems appropriate. We ask whether there is any indication of change in the German gender system in their speech, not whether these changes are restricted to the core group. This empirical focus is based on the assumption that if such an innovation is emerging at all, it should first become manifest in this group.

The data were collected in Stuttgart in 2009–2012 among 32 young speakers aged 13–18 and analyzed in detail in Siegel Reference Siegel2018. Of the group members, 28 were multilingual speakers from immigrant families of various— mainly Turkish and Balkan—backgrounds, born in Germany or living there with their families from a very young age. Four were monolingual Germans living in close network contacts with the multilingual speakers. All of them had acquired German from childhood and lived in highly multiethnic, low income neighborhoods in the city of Stuttgart. Data were collected in informal group conversations, mostly with an adult ethnographer present. According to Siegel (Reference Siegel2018), the participants’ speech showed typical multiethnolectal syntactic features occurring with considerable frequency, which suggests that they did not monitor their language for grammatical correctness according to Standard German rules during the recordings.Footnote 8 Although our corpus is restricted to speakers from Stuttgart, the features reported in Siegel Reference Siegel2018 are also attested in the speech of similar speakers in other German cities (see, among others, Wiese Reference Wiese2009, Wiese & Pohle 2016, Wiese & Rehbein 2016 for Berlin). Note that none of the participants in our study spoke a Swabian dialect (see Auer Reference Auer, Auer and Røyneland2020). There were no examples of gender agreement in anaphoric/cataphoric or relative pronouns in the data that did not conform to the Standard German norm. Externally controlled gender assignment to the nouns to which these pronouns referred followed the Standard German pattern. We therefore focus on internally controlled gender agreement.

3.2. Gender Agreement in Determiners

The most frequent grammatical context in which gender agreement is internally controlled is the determiner. There were 1,479 instances of noun phrases in our data set that included a definite or indefinite determiner. In only 15 of these cases (approximately 1%) did gender marking on the determiner deviate from the Standard German pattern. Examples of gender assignment in determiners that did not follow the Standard German rules are given in 2.Footnote 9

(2)

Nonstandard gender assignment always occurs with definite determiners and affects masculine (see 2a) or neuter (see 2b–d) nouns, while there are no instances of feminine nouns being affected. Yet, given the extremely small number of these cases, this finding seems irrelevant for the analysis of gender in the German multiethnolect as a whole.

We also looked at gender agreement in prenominal possessive determiners. Only 12 out of 560 tokens (approximately 2%) showed nonstandard zero inflection before feminine nouns. Zero inflection is only possible in the neuter and masculine nominative in Standard German (see tables 3 and 8). The deviations from the Standard German pattern in this case might indicate a (very weak) tendency to eliminate gender control in the possessive determiner. Examples of gender assignment in prenominal possessives that did not follow the Standard German pattern appear in 3.

(3)

The predominance of kinship nouns (Mutter ‘mother’, Tante ‘aunt’ or Schwester ‘sister’) on the list (7 of 12 examples) is due to the high general frequency of kinship terms.Footnote 10 For instance, there are 205 instances of possessives before the word Mutter in the corpus, but zero markings amount to only 3.4%, which is just a little higher than the occurrence of zero marked possessives in general. In sum, the determiners (including possessive determiners) give no evidence for a restructuring of the German gender system in the multiethnolect.

An independent grammatical innovation indirectly affects gender agreement by eliminating some of its contexts. There is a tendency not to use (definite and indefinite) determiners where Standard German would require them (see Wiese Reference Wiese2012:59–61, Siegel Reference Siegel2018:56–91). Some examples of bare noun NPs are listed below. Those NPs are different from Standard German determiner NPs, which are given in brackets in the English gloss.

(4)

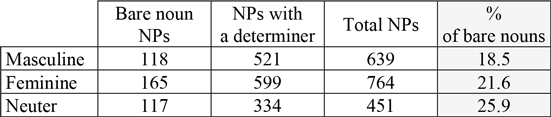

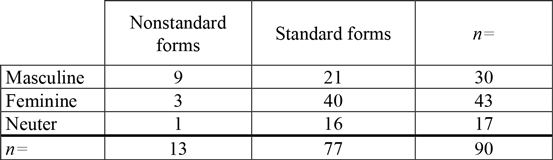

Table 4 shows the quantitative distributions of bare nouns according to (Standard German) gender.

Table 4. Nonuse of definite/indefinite determiners (from Siegel Reference Siegel2018:76).

The relatively small difference between the masculine and neuter determiners is significant (χ2 (2, 1854)=8.734; p<0.05; with low strength of association: Cramer’s V=0.069). Semantic reasons may be involved (see Siegel Reference Siegel2018:76–77). Yet it is clear that noun phrases of all genders are affected.

The percentages of bare nouns in the Stuttgart multiethnolect can be compared with the numbers in a study on the Berlin multiethnolect by Wiese & Rehbein (2016:50), which shows that the use of bare nouns is not restricted to Stuttgart. However, those authors found a considerably lower percentage of bare nouns (4.23%). One explanation for this quantitative difference is the inclusion of possessive determiners in their study: Possessive determiners are rarely omitted due to their high pragmatic salience.

Without going into details, it should be noted that determiners are a vulnerable domain of German grammar, as the original pragmatic function of the determiner—that is, to mark definiteness versus indefiniteness—has become irrelevant in many contexts over the course of language history. Leiss (Reference Leiss, Bittner and Gaeta2010) argues that both the definite and the indefinite determiners are “overdetermined” today, that is, their use has become to contexts in which definiteness is determined by syntactic and semantic factors. Paradoxically then, the historical success of the determiner system has undermined its raison d’être, and hence, according to Leiss, will in the long run lead to the collapse of its original function of expressing definiteness. From that perspective, the tendency of speakers to use bare nouns instead of NPs with determiners simply means that the German multiethnolect is following a predetermined path of language change. Leiss’ theory predicts that bare nouns should become more frequent without functional restrictions due to the erosion of the functional basis of the determiner. Alternative approaches have tried to explain the occurrence of bare nouns instead of determiner NPs in terms of pragmatics, for instance, by invoking the referential strength of the noun (see Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2013:168 and Swart Reference Swart, Borik and Gehrke2015 for Dutch; Demske Reference Demske, Szczepaniak and Flick2020, for further discussion). Auer & Cornips (2020) show that, at least in the syntactic context of prepositional phrases, this pragmatic approach does not sufficiently explain bare nouns in the multiethnolect.

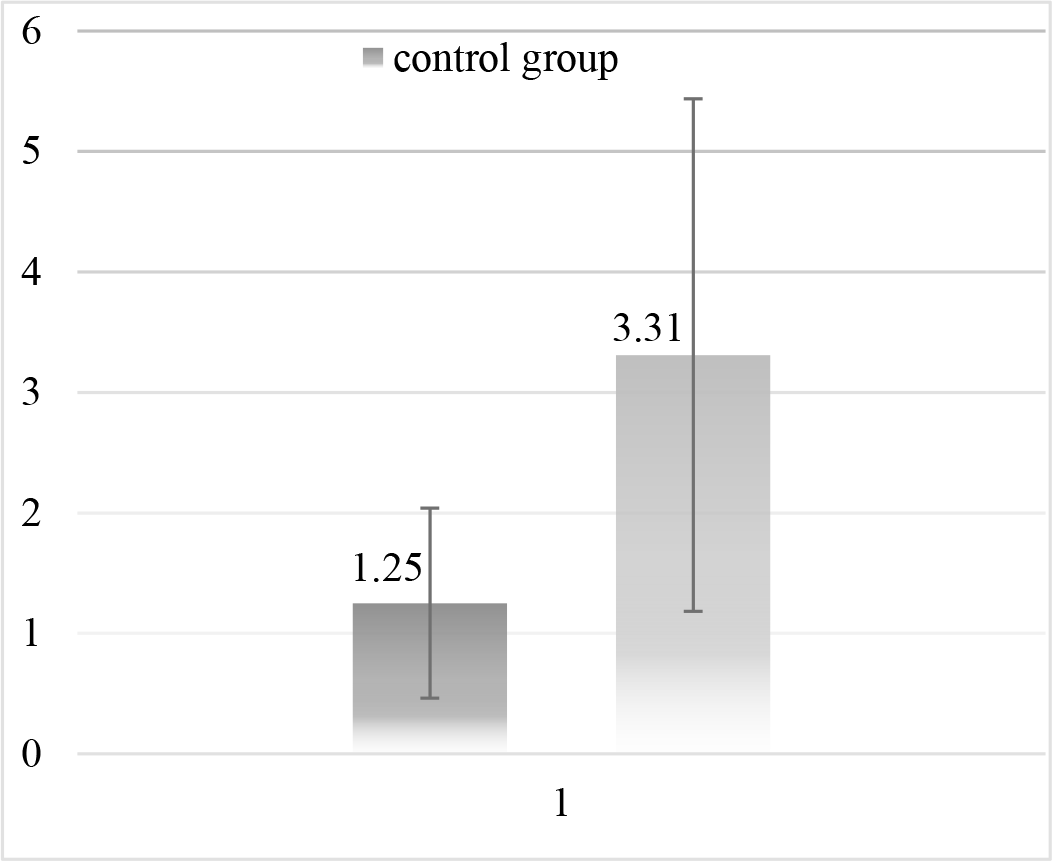

Against the background of the general vulnerability of the determiner system, it might appear questionable whether the vernacular nonuse of determiners in contexts in which they are required in Standard German can be attributed to multiethnolectal influence alone. We therefore checked our results against a control group of monolingual students living in a nonimmigrant neighborhood near Stuttgart, none of whom had a migration background. To assure comparability with the multiethnolectal data, we recorded group interviews with 12 speakers aged 13–15 from a Realschule. Figure 1 shows the occurrence of bare nouns per 1,000 words in the two data sets.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Average occurrence of bare nouns per 1,000 words in a monoethnic German (left) and a multiethnic group of young speakers.

With an average of 1.25 (SD=0.79) in the control group as compared to 3.31 (SD=2.13) in the multiethnic group, bare nouns are almost three times as frequent in the multiethnolect (a difference that is significant at the <.0001 level, t-test for unequal sample variance, t=-4.46, df=36.6). Approximately the same ratio was found in Wiese & Rehbein 2016:49. The nonuse of the determiner indirectly weakens the multiethnolectal gender system by eliminating a number of contexts in which gender is used. This tendency is significantly less pronounced in a comparable group of monoethnic German speakers.

However, the results for the control group show that bare nouns that do not follow the rules of Standard German also exist in vernacular German outside the multiethnolect. This indicates that various sources can lead to the same structural innovation (that is, bare nouns). For instance, the students in the control group often used school-related expressions without determiners: in fünfte ‘in fifth grade’ (Standard German in der fünften [Klasse]), in Gruppenarbeit ‘in group work’ (Standard German in der Gruppenarbeit), etc. These bare nouns seem to be a general feature of modern German “school language” and an innovation independent of the multiethnolect.

3.3. Gender Agreement in Attributive Adjectives

Standard German case and gender marking of attributive adjectives varies depending on which determiner precedes the adjective. We first looked at the adjectives in noun phrases introduced by a determiner. In this case, many case/gender distinctions on the adjective are neutralized even in Standard German. Forms deviating from the standard were observed only in the accusative in our data, and mostly before a masculine noun (13 out of 90, that is, approximately 14%). Almost all of them (12 out of 13) occurred after the indefinite determiner. Table 5 shows deviations from the Standard German gender agreement pattern in attributive adjectives after a determiner in the accusative singular.

Table 5. Deviations from the standard pattern, n=90 (57 after the indefinite determiner; 33 after the definite determiner).

The most frequent nonstandard form is the suffix -e instead of -en before a masculine noun (as in ein-en gut-e Freund instead of ein-en gut-en (acc) Freund ‘a good friend’). There is no tendency to delete the case- and gender-marking suffix entirely (as is sometimes observed in case of the possessive determiner, see above). In two of the three cases listed in Table 5 as nonstandard feminine forms, the neuter es-suffix is chosen before a (Standard German feminine) noun, but the determiner also follows the neuter pattern; that is, the speaker apparently has assigned a nonstandard lexical gender to the noun, as in n schönes Zukunft(n) instead of the Standard German ne schöne Zukunft(f).Footnote 13 All in all, the tendency to overgeneralize the schwa-suffix is minor in this context, at best, and no systematic restructuring is visible.Footnote 14

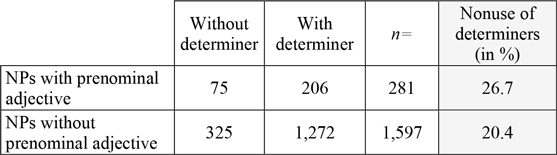

We then looked at the attributive adjectives in NPs with no determiner—an option not allowed in Standard German. Before we proceed, it should be noted that in the German multiethnolect, the determiner is omitted in 26.7% of NPs that contain an attributive adjective. This number is slightly higher (but still statistically significant) than in bare noun NPs. Table 6 shows nonuse of determiners in NPs with and without prenominal adjectives (see Siegel Reference Siegel2018:71).

Table 6. Nonuse of determiners in NPs (χ² (1, 1878)=5,729; p<0,05; low strength of association: Phi=0,055).

Attributive adjectives in NPs with no determiner present a much more interesting case in terms of gender agreement. If no determiner is used, the speakers could follow the pattern of the Standard German adjective inflection without a preceding determiner (see table 2, left-hand column, the strong paradigm), which requires a rather complex system of gender- and case-marking. Alternatively, they could simplify this system according to the weak or mixed inflection prescribed in Standard German after the determiner. In the latter case, they would treat the noun phrase as if the determiner were still there, and the deletion could be regarded as a phonological process only.

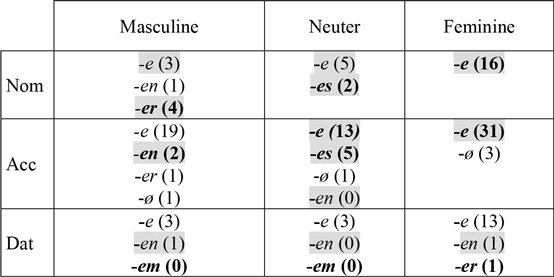

The solution chosen by our speakers is shown in table 7, which summarizes all inflectional suffixes of attributive adjectives in NPs without determiners in the data set, by case and gender.Footnote 15 The Standard German suffixes for adjectives not preceded by a determiner (see table 2) appear in boldface; the Standard German suffixes for adjectives preceded by a (definite or indefinite) determiner (see tables 2 and 3) have grey shading. All other forms are nonstandard.

Table 7. Suffixes of prenominal adjectives in NPs without determiners in the multiethnolectal data set (n=129).

It is clear that the speakers do not follow the Standard German strong paradigm of adjective inflection required for NPs not containing a determiner. The forms expected under this paradigm only account for 47% of those found in the data set (61 of 129); and even this percentage is only reached because the feminine suffix for the nominative and accusative of the strong paradigm (schwa) is identical with this suffix in the weak and mixed paradigms. Leaving out the feminine nominative/accusative, only 17% of the forms (14 out of 79) are well-formed according to the strong paradigm in the standard. The weak/mixed paradigms account better for the data: Assuming that speakers follow the weak/mixed paradigms, 64% of the forms (83 of 129) are explained. However, neither account captures precisely the pattern our speakers choose. Indeed, they follow a different strategy, which is to select the schwa-suffix as much as possible. If the Standard German strong inflection already has schwa (as in the accusative and nominative of the feminine), this option is almost always selected; if the weak or mixed inflection shows schwa in Standard German (as in the dative of the feminine, in the nominative of the masculine, or the nominative/accusative of the neuter), it is also selected. However, if neither of the Standard German adjectival paradigms has schwa, as in the masculine accusative or masculine/neuter dative, it is still schwa which is chosen as the adjectival suffix. Examples of nonstandard schwa inflection of the prenominal adjective in the multiethnolect are given in 5.

(5)

In total, 82% (106) of all prenominal adjectives in our data set receive the schwa-suffix, regardless of case or gender. It is therefore fair to assume that the schwa-suffix as used by these speakers is a passe-partout suffix that only has the function of marking the attributive function of the adjective.Footnote 16

It can be concluded that speakers switch between two systems. They either use the determiner, and thus follow the Standard German pattern of adjectival inflection in prenominal position, which shows only little gender marking due to numerous syncretisms anyway. Alternatively, they do not use the determiner, and in this case simplify adjectival inflection quite radically, to the degree of almost always using gender- and case-neutral schwa as a marker. In this case, one can indeed speak of a restructuring of the morphological system, which is applied in tandem with the omission of the determiners. Noun phrases without determiners but with a prenominal adjective almost regularly lose their gender- (and case-) marking in favor of a generalized attributive suffix -e. With the determiner missing, these NPs therefore usually have no overt gender marking at all.Footnote 17

4. Conclusion

Seen against the background of L2 acquisition of gender as sketched in section 2, the results indicate that the German multiethnolect is not a learners’ variety—which, of course, is to be expected given the speakers’ language biographies. Nor have we found evidence of an ongoing or incipient language change affecting the gender system of the German multiethnolect, even though the participants in our study frequently used a number of other innovative grammatical features (of which only the nonuse of determiners was discussed in this paper). This contrasts with what has been reported for Dutch or Danish multiethnolects. The number of cases of gender assignment that diverge from Standard German in our data is very low. Considering that the German multiethnolect is often said to spearhead vernacular language change, this finding is evidence of the stability of the three-gender system of German. When explaining this stability, it must be kept in mind that:

(i) German has not reduced the three-gender system to a neuter/utrum system as in Dutch or Norwegian (Bokmål), with the ensuing frequency imbalance between the two remaining genders, which weakens the neuter; and

(ii) the German determiners have remained in prenominal position in all contexts (other than in the North Germanic languages) and are clearly separable from the nouns.

However, we have also shown that there is a tendency in the multiethnolect to eliminate grammatical contexts for gender agreement through an independent process, that is, the tendency to replace determiner NPs by bare nouns. Bewer (Reference Bewer, Gagarina and Bittner2004:84) thinks that about 15% of the words in (nonethnolectal) German running speech are either nouns with an inherent gender or words whose gender is controlled by these nouns. It is likely that this percentage is significantly lower in multiethnolectal speech due to this process.

The only possible innovation in the German multiethnolect affecting gender that we found was the simplification of the inflection of prenominal adjectives in noun phrases without determiners; the traditional German system is being replaced by the generalized suffix -e marking attribution only. The same restructuring of the prenominal inflectional paradigm of the adjective is known from the spontaneous acquisition of German by adult immigrant learners, and indeed, one possible explanation for its occurrence is that it was copied from the learner variety of the first generation of migrants (still very much present in our speakers’ families and neighborhoods) into the multiethnolect. However, the same overgeneralization of the schwa suffix is also found in L1 acquisition of the German gender system (Mills Reference Mills1986, Müller Reference Müller and Jürgen1994, Bewer Reference Bewer, Gagarina and Bittner2004, Bittner Reference Bittner2006, Szagun Reference Szagun2013, Ruberg Reference Ruberg2015). Children start out with bare nouns. The use of the determiner then gradually increases from two to four; in the predeterminer phase, they may use NPs with an adjective ending in schwa, such as groß-e Haus ‘big house’; Standard German (ein) groß-es Haus/das groß-e Haus. In all these cases, the choice of schwa is easily explained: Schwa is the most frequent suffix in the paradigm, and since it also marks the plural nominative in all genders, it also has the largest token frequency. It therefore is a natural target of analogical leveling just as well as a natural intermediate stage in (L1/L2) language acquisition.