1. Introduction

Middle Low German is generally considered to be a successor of Old Saxon (see, among others, Fulk Reference Fulk2018:29). One of the criteria used to define language succession is continuity: Linguistic forms and their patterns of use found in the older language are expected to appear, perhaps with some modification, in its successor(s). In the case of Old Saxon and Middle Low German, continuity has been a problematic issue, as Old Saxon generally has more North Sea Germanic innovations than Middle Low German (see section 2.3 for details). How some of these differences can be best accounted for is somewhat disputed. On the one hand, some scholars hypothesize that the differences between Old Saxon and the later dialects, including Middle Low German, are due to the influence of High German on the latter (Wolff Reference Wolff1934, Stiles Reference Stiles, Volkert, Alastair and Wilts1995, Stiles Reference Stiles2013). On the other hand, others have questioned whether written Old Saxon, which serves as the basis for comparison, ever reflected an actual spoken language; instead, it was an artificial grapholect influenced by Old English and Franconian conventions. This explains the odd mixture of features not found in later dialects (Collitz Reference Collitz1901, Rooth Reference Rooth1973, Doane Reference Doane1991:45–46).

The goal of this paper is to evaluate the two hypotheses on the basis of the system of degree adverbs in Old Saxon and Middle Low German, which has not yet been considered in the context of this debate. More specifically, I focus on adverbs of high degree (boosters), which strengthen a statement (such as very, exceedingly), and adverbs of absolute degree (maximizers), which indicate that a quality is wholly present (such as completely, fully). I examine individual adverbs in Old Saxon and Middle Low German as well as their usage patterns and show that there are substantial differences between the two languages. This presents a potential problem for continuity: If the system of degree adverbs in written Old Saxon is a direct predecessor of the Middle Low German system, then common Old Saxon degree adverbs should appear in Middle Low German, possibly with a specialized usage. However, upon a closer examination, degree adverbs in Old Saxon and Middle Low German in fact provide support for the grapholect hypothesis: I show that, while both hypotheses have their problems, the system in Old Saxon does appear to reflect an artificial poetic register rather than actual spoken language.

This paper is structured in the following way: Section 2 provides an overview of both Old Saxon and Middle Low German that focuses on their history and dialects. I also discuss the available corpus data for the two languages (sections 2.1 and 2.2), followed by a discussion of the continuity between the two (section 2.3). For the sake of comparison, the same section also contains an overview of adverbs of degree more generally, including data from Old English and Old and Middle High German (section 2.4). Section 3 presents the methodology and the corpora used for the analysis, and section 4 provides a description of the adverbs of degree in both Old Saxon and Middle Low German, and the history of these adverbs. Finally, section 5 addresses the central problem regarding the degree of continuity between the two languages and evaluates the two hypotheses.

2. Background

2.1. Old Saxon

Old Saxon is a West Germanic language attested from the 9th century until around 1050. It sits at the intersection between North Sea Germanic and Continental West Germanic, sharing features with both. Old Saxon is commonly described as having no unique innovations of its own (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1981:255) and is perhaps best defined in the negative: “not High German, nor Frisian, nor Dutch” (Stiles Reference Stiles2013:20). The term Old Saxon is generally favored over Old Low German, because the latter term is also sometimes used to include Old Dutch as well as Old Saxon to contrast these languages with Old High German, as neither of them participated in the High German Consonant Shift (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:83–84). Old Saxon is therefore a more specific term. The language is commonly associated with the Saxon tribes, who likely originated in present-day Holstein and were part of a shared culture and dialect continuum with the Angles and the Frisians (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:109–110, Peters Reference Peters2012:446). This continuum was subsequently broken with the departure of the Anglo-Saxons to Great Britain in the 5th century (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:109). In the 6th and 7th centuries, the Saxons migrated southward and dominated various Continental West Germanic tribes in later Westphalia, Eastphalia, and Angria (Peters Reference Peters2012:446). Following a series of wars with the Franks between 772 and 804, the Saxons were ultimately subjugated by Charlemagne and were made to convert to Christianity (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:107–108, Peters Reference Peters2012:448).

The Old Saxon language is primarily known from the Heliand, a gospel harmony written in Germanic alliterative verse composed in the first half of the 9th century, which places it not long after the subjugation period. This text survives in two more or less complete manuscripts: the Monacensis (M) from the second half of the 9th century (Doane Reference Doane1991:44) and the Cotton Caligula A. VII (C) likely produced in England or at least by an Anglo-Saxon scribe, an assessment based primarily on paleographical evidence (Priebsch Reference Priebsch1925:35). Additionally, there are four surviving fragments (Cathey Reference Cathey2002:22–24, Schmid Reference Schmid2006), indicating that the text was quite widespread. The most notable of these fragments is the Straubing fragment (S), which is the manuscript with the most North Sea Germanic features including ones that appear to resemble Old Frisian (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1988, Klein Reference Klein1990, Versloot & Adamczyk Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017).Footnote 1

Outside of the Heliand, a number of smaller Old Saxon fragments survive. The most notable of these is a poetic version of Genesis that is slightly newer. This text survives in three separate fragments written in essentially the same dialect as the Heliand (Doane Reference Doane1991:45). Additionally, Genesis famously survives in an Old English translation known as Genesis B (615 lines) that is rather crudely inserted into Genesis A (an unrelated poem). It also fully overlaps with Fragment 1 (26 lines), but its narrative does not reach the contents of Fragments 2 or 3 (the three Old Saxon fragments contain 330 lines when combined).Footnote 2 The existence of both Heliand C and Genesis B attests to a connection between the Old English and Old Saxon textual traditions, though the exact circumstances in which these manuscripts were produced remain speculative. A number of nonliterary fragments also survive, the longest of which is the 11th-century Freckenhorster Heberegister from north-eastern Westphalia (Klein Reference Klein1990:201), though none of them contain any adverbs of degree.Footnote 3

While the different manuscripts show great orthographic variation, it is unclear if these represent dialectal variation or influence from other scribal traditions: As Fulk (Reference Fulk2018:29) states, it is impossible to establish distinct dialects for Old Saxon. Yet, a distinction between west and east has been observed for the nonliterary fragments (Versloot & Adamczyk Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017). The largest part of the Old Saxon fragments comes from the southwest, mainly Essen and Werden (Versloot & Adamczyk Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017:128).

The Old Saxon written language contains a mixture of North Sea Germanic and Continental West Germanic features, but interpretations of what exactly this implies differ. Collitz (Reference Collitz1901:133–134) argues that this combination of features in the Heliand points to it having been written in an artificial literary language akin to Homeric Greek, one that is derived from early Germanic epic poetry. For example, Old Saxon’s 1st person singular preterite indicative form of kunnan ‘to know’ is the Franconian form konsta, with a retained nasal before the spirant -s-, in addition to other forms with the sound combination -nst- (Collitz Reference Collitz1901:130–131). However, Collitz (Reference Collitz1901:131) points out that in other words nasals are generally lost before spirants, as in Old English and Old Frisian (see section 2.3)—an unusual combination of features not found in any later dialect; moreover, no later dialect possesses a reflex of konsta while also showing evidence of nasal deletion in relevant contexts.Footnote 4 He further argues that the fact that smaller Old Saxon fragments are written using a similar mix of features shows that the language was not created extemporaneously (for example, by having a speaker of one dialect copy a text written in another and blending the two), as the variation is consistent. For example, the Franconian form bigonsta ‘began’ (with a retained nasal) is attested alongside othra ‘other’ (with a deleted nasal) in the Essen Confession (Collitz Reference Collitz1901:133).

This view is broadly shared by Doane (Reference Doane1991:45), who points to the fact that Genesis was written in a mostly identical dialect to argue that “there seems to have been for a brief time an artificial language for alliterative poetry that was used by at least two poets.” However, Doane (Reference Doane1991:45–46) speculates that this grapholect was developed under the influence of Franconian scribal traditions and Old English poetry, leading to a language that was widely understood at the time, which Doane describes as “idealized Saxon speech” (p. 45).

It is conceivable that contact with Old English occurred in monasteries, because Anglo-Saxon scribes were active in German monasteries in the 8th and 9th centuries, particularly in the Rhineland, Hesse, and Thuringia (see McKitterick Reference McKitterick1989), which may have influenced the Old Saxon written language. Rooth (Reference Rooth1973:238–244) argues that genuine North Sea Germanic phonological outcomes and inflectional endings are often obscured by Franconian orthography (including hypercorrect substitutions of Franconian <uo> for <o> in Heliand C), and he states that the language of the Heliand was born in a Franconian cultural environment. The mixed character of Old Saxon would thus be more a product of Franconian orthographic influence. The scribal influence from both Old English and Franconian allow for the interpretation of written Old Saxon as a literary grapholect.

Others, however, do not presuppose that written Old Saxon was an artificial language; instead, they attribute the mixture of forms to prolonged influence from High German, where the more North Sea Germanic features have been gradually replaced by Continental ones (Wolff Reference Wolff1934:154, Stiles Reference Stiles, Volkert, Alastair and Wilts1995:202, Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller and Jan2007:32, Stiles Reference Stiles2013:20). The exact timing of this influence has been a matter of some debate. According to Stiles (Reference Stiles2013:20), it predates the written record and continues throughout the Middle Ages and into modern times. This influence should therefore already be present to a degree in Old Saxon, it should continue during the transition to Middle Low German, and it should continue to affect the development of Middle Low German.

In contrast, Krogh (Reference Krogh1996:403–404) argues that Old Saxon’s position between Continental and North Sea Germanic is as old as the common West Germanic period, and that influence from High German only began after the subjugation of the Saxons. Versloot & Adamczyk (Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017:126) also argue for early linguistic stability, pointing to Old Saxon’s lack of early unique innovations as evidence. However, Peters (Reference Peters2012:447) considers it likely that dialect mixing with Continental West Germanic languages occurred when the Saxons migrated southward and dominated the other tribes. Regardless, it is generally agreed that the underlying structure of Old Saxon comes from North Sea Germanic (or from a transitional dialect) and that it was subsequently subject to High German/Franconian influence (Wolff Reference Wolff1934, Rooth Reference Rooth1973, Doane Reference Doane1991:45, Krogh Reference Krogh1996:403–404, Krogh Reference Krogh2013, Stiles Reference Stiles2013). This approach gives rise to the other hypothesis considered here, namely, that the apparent lack of continuity between Old Saxon and Middle Low German is due to the influence of High German that continued to affect the developmentary trajectory of Low German.

2.2. Middle Low German

Middle Low German is considered to be the successor to Old Saxon, at least as far as the spoken language is concerned. Its attestation period begins around 1200, following a hiatus of around 150 years after the last Old Saxon fragments, and ends around 1650 (Peters Reference Peters, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1420). Compared to Old Saxon, Middle Low German has expanded northward, toward the northwest, and eastward into Slavic territories (Ostsiedlung), but it lost some territory in the southeast (Peters Reference Peters, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1409–1410, 1415–1418; Peters Reference Peters2012:454).Footnote 5 Like other Middle Germanic languages, Middle Low German is characterized by a reduction of unstressed vowels, which also led to a reduction of the inflectional morphology when contrasted with Old Saxon. Section 2.3 further discusses the continuity between the two.

Unlike Old Saxon, Middle Low German clearly comes in a variety of dialects. The following groups are traditionally distinguished, based on Lasch Reference Lasch1974:13–20: Westphalian, Eastphalian, North Low Saxon, Brandenburgish & East Anhaltish (South Markish).Footnote 6 Due to the nature of the language of the Heliand, as described in section 2.1, it is difficult to determine which Middle Low German dialect is expected to show the greatest continuity with it. Versloot & Adamczyk (Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017:146) claim that the language of the Heliand represents a south-western variety of Old Saxon, but if it is, in fact, a literary grapholect, such a question may be moot.

The written version of Middle Low German, however, does not continue the Old Saxon orthographic conventions (Peters Reference Peters, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1409). By 1370, Middle Low German had become the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League, which marks the beginning of a classical period and coincides with the written language becoming more conventionalized. The dialect of Lübeck (North Low Saxon mixed with features from other dialects) became the dominant dialect during this period (Peters Reference Peters, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1414–1415; Peters Reference Peters2012:453). Preclassical Middle Low German texts are perhaps the most accurate reflection of the spoken language, postdating influence from a potential Old Saxon literary grapholect and predating the Lübeck conventions. At the beginning of the 16th century, a shift began toward High German as the main written language, which was completed around 1650 and which coincides with the decline of the Hanseatic League (Sodmann Reference Sodmann, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1505–1506, 1509). This shift occurred across all domains, though at different times (see Sodmann Reference Sodmann, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000).

The dialect that was most often used for writing shifted multiple times during the Middle Low German period. In the 13th century, this was Eastphalian, but by the 14th century, Westphalian and North Low Saxon dialects had become more prominent due to the emergence of religious literature in these areas (Cordes Reference Cordes, Cordes and Möhn1983:352). During the 15th century, the center shifted firmly to Lübeck and the northeast in general (Cordes Reference Cordes, Cordes and Möhn1983:352), and most Middle Low German texts are from this period due to the prominence of the Hanseatic League (Meier & Möhn Reference Meier, Möhn, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1471). As Middle Low German writing declined during the 17th century, it was the north that held on to it the longest (Cordes Reference Cordes, Cordes and Möhn1983:352). See Cordes Reference Cordes, Cordes and Möhn1983 for an overview of the Middle Low German corpus in general and Meier & Möhn Reference Meier, Möhn, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000 for an overview of the classical period specifically.

2.3 The Loss of North Sea Germanic Features in Middle Low German

As mentioned in the introduction, Old Saxon shows more North Sea Germanic innovations than Middle Low German, which poses a potential problem for linguistic continuity between the two languages. This apparent lack of continuity is often explained as further influence from High German (see Stiles Reference Stiles2013); but it could also arise because written Old Saxon was an artificial language that did not reflect actual speech.

When discussing potential High German influence, it is important to note that language contact in the medieval period fundamentally differs from language contact in modern times, as full bilingualism is thought to have been comparatively rare (Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller and Jan2007:27). As such, receptive multilingualism was the norm, and the absence of standard languages meant that dialect mixing was likely considerably more common (Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller and Jan2007:32). The contact between Low German and High German in this period is therefore best described as dialect contact, as used by Trudgill (Reference Trudgill1986:1–2), rather than language contact. The latter generally involves bilingualism, while the former describes contact between varieties that are at least partially mutually intelligible (1986:1–2). A common pattern in dialect contact is leveling—a process in which marked features tend to be lost over time—which can apply to phonology, morphology, and the lexicon (Kerswill & Williams Reference Kerswill, Williams, Mari and Esch2011:88). One important concept here is salience, as those features that are strongly regionally marked or stigmatized are typically avoided (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986:11, Kerswill & Williams Reference Kerswill, Williams, Mari and Esch2011:89).Footnote 7 Which features are considered salient is primarily determined by sociolinguistic factors (that is, stigma and prestige) rather than linguistic ones (such as phonetic distance; Kerswill & Williams Reference Kerswill, Williams, Mari and Esch2011:105–106). When applied to the contact situation between Low German and High German, this principle could account for the apparent loss of North Sea Germanic features in Middle Low German in favor of more Continental ones that are also present in High German and Dutch. Three North Sea Germanic features relevant for this comparison are discussed in detail below:Footnote 8

(i) deletion of nasals before spirants;

(ii) uniform plural ending in verbs;

(iii) absence of a separate reflexive pronoun.

Like Old English and Old Frisian, Old Saxon shows deletion of nasals before spirants followed by compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel. This can be seen in table 1 below, where the forms in these languages are contrasted with their counterparts in Proto-Germanic and Old High German, though this change is not entirely consistent.Footnote 9 In contrast, these nasals are generally present in Middle Low German, although there are exceptions here as well. For example, uns is generally found in place of Old Saxon ûs ‘us’ (Stiles Reference Stiles2013:19), but Lasch (Reference Lasch1974:215) notes that ûs still occurs, particularly in early preclassical texts and that it is completely absent in South Markish.Footnote 10 The presence of these nasals in Middle Low German could be explained as restoration by assuming that the resulting elongated vowels were still nasalized in Old Saxon after the deletion of the nasal consonant, which could have triggered said restoration (Stiles Reference Stiles2013:20). This restoration process, however, would not have been regular: First, even after restoration, a number of Middle Low German forms still contain no nasal in these positions. Some of these forms are shared with Middle Dutch, as shown in table 1. Second, restoration did not affect all the forms of the same word. For example, the Middle Low German word for ‘goose’ often appears as gôs, but the plural is often gense (Lasch Reference Lasch1974:143). The word for ‘goose’ is not attested in Old Saxon in either the singular or the plural. Note that a loss of nasals before Proto-Germanic +h is found in all Germanic languages, as can be seen in the 1st person singular preterite indicative form of Old High German denken ‘to think’, which is dâhta (Braune Reference Braune2018:168), but this predates the North Sea Germanic development. The unexpected forms in table 1 are in boldface.Footnote 11

Table 1. The loss of the etymological +-n- before spirants compared between different West Germanic languages.

The next North Sea Germanic feature that sets apart written Old Saxon and Middle Low German is the so-called unity plural (Einheitsplural)—a uniform ending in plural forms of verbs. In Old Saxon this ending is -að (compare Old English -aþ, Old Frisian -ath) for all three persons in the present indicative (Gallée Reference Gallée1993:246). Note that a unity plural is also found in Middle Low German, but it looks very different. Broadly speaking, in western dialects this ending is -et, while in eastern ones it is -en (Lasch Reference Lasch1974:226–227). The ending -et corresponds to Old Saxon -að; the ending -en becomes more prominent during the classical period due to influence from the Lübeck variety (Peters Reference Peters, Besch, Betten, Reichmann and Sonderegger2000:1414). Crucially, forms ending in -n are not attested in any of the Old Saxon texts; instead, the endings -ad and -ed are used interchangeably, based on data from the Old German Reference Corpus (Donhauser et al. Reference Donhauser, Gippert and Lühr2018). Examples from the Freckenhorster Heberegister include harad (29) and hared ‘hear’ (24); in the Gernroder Predigt, there are examples including sprekad ‘speak’ (5.7.3) and hebbed ‘have’ (5.10.18).Footnote 14 By contrast, Old High German maintains three distinct endings: -emês/-ên, -et, -ent for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person, respectively (Braune Reference Braune2018:356), and Middle Low German -en bears resemblance to the 1st person singular form.Footnote 15

Finally, the absence of a separate reflexive pronoun is another North Sea Germanic feature (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1981:114) exhibited by Old Saxon. In relevant contexts, written Old Saxon exclusively uses 3rd person personal pronouns in place of reflexives (Gallée Reference Gallée1993:237), as shown by an example from the Heliand, in 1a (though an isolated High German sih is found in the Essener Evangelienglossen; Krogh Reference Krogh1996:325).Footnote 16 By contrast, Middle Low German does have a separate reflexive, sik (or sick; Lasch Reference Lasch1974:213), as shown by an example from Westphalian Middle Low German, in 1b.

(1)

Stiles (Reference Stiles2013:20) and Wolff (Reference Wolff1934:139) use the Middle Low German reflexive sik/sick as an example of High German influence, which must have occurred during the transition from Old Saxon to Middle Low German. Note, however, that this requires an explanation as to how Old High German sih or Middle High German sich had its final consonant replaced with the etymologically correct -k (compare Gothic sik), especially considering that Middle Dutch straightforwardly borrowed the High German form sich (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:323–326). Krogh (Reference Krogh1996:326–327) argues instead that the reflexive pronoun sik may have been preserved in Eastphalian Old Saxon and is therefore a native form. This view is supported by the observation that the accusative forms of 1st and 2nd person singular personal pronouns mik and thik/dik, which are derived in a similar way, also show a final -k where High German has a final -(c)h. Both Old Saxon and Middle Low German use their respective pronoun forms inconsistently, and they often have the dative forms mî and thî/dî in place of expected accusatives.Footnote 17 The forms with final -k also tend to be common in Eastphalian, though Peters (Reference Peters2012:453) notes that this is not always reflected in writing in Middle Low German. The downfall of the accusative forms mik and thik has been given as the reason for the loss of the reflexive +sik in Old Saxon, since it would no longer fit with the other forms (Wolff Reference Wolff1934:139). If +sik were only preserved in a part of the Old Saxon language area, its usage may have been suppressed in writing (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:326).

These differences between Old Saxon and Middle Low German place the latter closer to the Continental West Germanic languages than the former. The question remains whether High German influence alone can truly account for all of these discrepancies. Alternatively, they could also indicate that the Old Saxon literary language may not be a direct predecessor of Middle Low German. One angle that has not yet been considered is continuity between the adverbs of degree in Old Saxon and Middle Low German, which may provide further insights in this matter.

2.4. Adverbs of Degree

To investigate a potential lack of continuity between Old Saxon and Middle Low German using the data from degree adverbs, let me first discuss degree adverbs in general—their usage patterns and how they tend to change over time. Individual adverbs of degree come with their own restrictions on usage, which include syntactic ones, such as sensitivity to the lexical category of the modified phrase, and semantic ones, such as sensitivity to negative or positive polarity (see Klein Reference Klein1998:8–14, 71, 85, among others). The former is illustrated in 2, which shows that this restriction is subject to crosslinguistic variation: English very can combine with adjectives, as in 2a, but not with verbs, as in 2b (Klein Reference Klein1998:12–13), while German sehr ‘very’ can combine with both, as in 2c,d. However, sehr cannot combine with comparative adjectives, while viel ‘much’ can, as shown in 2e.

(2)

The semantic restriction—adverbs’ sensitivity to polarity—is illustrated in 3. Polarity in this context refers to both polarity of the environment (that is, whether or not the sentence is negated) and the inherent polarity of the modified phrase.Footnote 18 Examples of adverbs that display sensitivity to each type of polarity are given in 3a,b and 3c,d, respectively.

(3)

Sensitivity to inherent polarity is likely due to the original lexical meaning of the adverb in question (Klein Reference Klein1998:79). It is also noteworthy that sensitivity to different types of polarity does not always play out as a hard restriction; it can also be a tendency.

As stated in the introduction, the present study focuses on two types of adverbs of degree: adverbs of high degree (boosters), which are those that strengthen a statement (for example, very, exceedingly), and adverbs of absolute degree (maximizers), which indicate that a quality is wholly present (for example, completely, fully). One clear difference between the two types of adverbs is that the latter require closed-scale adjectives and adverbs (that is, endpoint-oriented modifiers), as in 4a, while the former require open-scale ones (that is, those without an endpoint; Kennedy & McNally Reference Kennedy and McNally2005), as in 4b.

(4)

Klein (Reference Klein1998) and Van Os (1988) make an additional distinction between high degree and extremely high degree adverbs. Additionally, one can distinguish adverbs of low degree (downtoners), which weaken a statement (for example, hardly, somewhat). These additional distinctions are less relevant for this analysis.

The semantics of degree adverbs is generally likely to change over time, and these changes tend to follow a particular grammaticalization pattern. Specifically, degree adverbs first tend to expand in usage (that is, they become capable of modifying a wider variety of categories), while their lexical meaning is bleached over time (Klein Reference Klein1998:25–26, Lorenz Reference Lorenz, Wischer and Diewald2002:144, Hopper & Traugott 2003:104). Afterwards, they become restricted to a specialized usage as new adverbs of degree emerge (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:18). Thus, at any given point in time, different adverbs show different degrees of grammaticalization (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:22, Lorenz Reference Lorenz, Wischer and Diewald2002:145). An example of a highly specialized adverb is veel ‘much’ in Dutch: In Middle Dutch, as vēle, it was capable of modifying a wide variety of categories, but now it is restricted to comparatives and comparative-like constructions (Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:204–205, 212). This development path is similar to the one of viel in Modern German.

It has generally been observed for High German (Van Os 1988), English (Stoffel Reference Stoffel1901), and Dutch (Hoeksema Reference Hoeksema2011) that the number of adverbs of degree began to increase in the Early Modern period, while before then their number was fairly stable. This stability is illustrated by the situation in Old and Middle High German, as shown in table 2 below. The table provides an estimation of the relative distribution of five adverbs of high degree per century in percentages, along with the total number of attestations for each century. The numbers are based on data from the Old German Reference Corpus (Donhauser et al. Reference Donhauser, Gippert and Lühr2018) and the ReM (Wegera et al. Reference Wegera, Wich-Reif, Dipper and Klein2016), including both annotated and unannotated data (see section 3.2). For Middle High German vile, only instances in which it modified adjectives and adverbs were included, as its status as a verb modifier can be ambiguous (see section 4.1).

Table 2. Relative distribution of five adverbs of high degree per century in percentages.

The adverb filu/vile ‘much, very’ remains the most dominant adverb of high degree throughout the Old and Middle High German periods, and harto/harte ‘firmly, very’ remains the second most frequent one, though note that data from the 8th and 10th centuries are scarce. The largest changes are the increase in usage of sêre ‘very, sorely’, which begins after 1150, and the decline in usage of drâto ‘very, quickly’ as an adverb of degree (though drâte remains in use in Middle High German with the meaning ‘quickly’; Lexer Reference Lexer1992, s.v. drâte).Footnote 19 In Old English, swîþe ‘very, strongly, quickly’ is the most dominant adverb of high degree followed by ful ‘fully, very’ (Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003).Footnote 20 Usage of swîþe continues throughout the Middle English period, though it is overtaken by ful around 1250 as the more dominant adverb (Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003:386). Usage of swîþe begins to decline after 1350, though examples are still found until 1525 (Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003:379, Mustanoja & Van Gelderen 2016:325–330). While in the medieval period, English is known for having been subject to considerable outside influence, it still displays a certain stability in its system of adverbs of degree. As such, at least a similar extent of continuity would be expected between Old Saxon and Middle Low German, if the latter is a direct successor to the former. The usage of Old English swîþe and High German filu/vile, harto/harte, and sêro/sêre is discussed in more detail in section 4, in relation to their Old Saxon and Middle Low German counterparts.

Using the observations on degree adverbs outlined above—in particular, on how they tend to change over time—the present study seeks to account for the apparent lack of continuity between Old Saxon and Middle Low German. As stated in the introduction, two hypotheses are examined: This apparent lack of continuity is due to i) High German influence on Middle Low German or ii) the artificiality of written Old Saxon. The basic premise is based on how language continuity is understood: If the system of adverbs of degree in written Old Saxon is a direct predecessor of the Middle Low German system, there should be a direct line from the former to the latter, and common Old Saxon adverbs of degree should still appear in Middle Low German, possibly with a specialized usage. Also, any variation in the use of degree adverbs should be similar to variation observed in English and High German discussed above. An overview of the adverbs included in the analysis is given in section 3.2 below. While adverbs of degree on their own are not enough to make definitive claims about the nature of written Old Saxon, they do provide new insights into the continuity between the two languages.

3. Method

The list of corpora used for the analysis can be found in table 3. The Old German Reference Corpus (Donhauser et al. Reference Donhauser, Gippert and Lühr2018) contains a complete record of Old High German and Old Saxon, while the ReN (2019) contains a selection of Middle Low German material. The latter also includes Rhinelandic material, but this was not included in the analysis.Footnote 21 The corpora listed in table 3 were searched for Old Saxon and Middle Low German adverbs. High German and Old English data were also collected from the corpora and are included for reference.

Table 3. The corpora used for the analysis along with the number of tokens for each language.

along with the number of tokens for each language.

The adverbs included in the analysis are presented in table 4. The Old Saxon list is based on the Heliand and Genesis, as adverbs of degree are not attested outside of these texts. Four marginal adverbs were excluded: fasto ‘firmly, very’, firinun ‘very’, thurhfremid ‘completely’, and unmet ‘immensely’, as they were attested with very few tokens, and the status of fasto as an adverb of degree is unclear.Footnote 23 The Middle Low German list includes all the adverbs listed for Old Saxon as well as those adverbs that allow for a comparison with Middle Dutch, Middle High German, and Middle English.

Table 4. The adverbs of degree included in the analysis for both languages.

The following information was collected for each token: adverb degree, the modified phrase, and the polarity of the environment. For the modified phrase, its lexical category, corpus frequency of the lemma, its Modern English translation, and its inherent polarity were included. When recording the lexical category of the modified phrase, adjectives and adverbs were further subdivided into positives, comparatives, superlatives, and those modified by the equivalent of too. Tokens where the modified phrase was another adverb of degree were treated as a separate category. Both the adverb and its modified phrase were recorded in their original spelling and in a normalized spelling based on the normalization used in the respective corpus. Meta information such as the text, context, lines, century, dialect, and writer (if known) was also recorded.

For Old Saxon, all information was collected manually. For Middle Low German and Middle High German, this was done using a script written in R (R Core Team 2020) to read files generated by the corpora’s Grid Exporter because of the larger corpus size. It finds the modified phrase by looking for the nearest eligible word within the clause starting with the word directly to the adverb’s right. Other adverbs directly to its left were excluded to prevent two adverbs from potentially modifying each other; auxiliary verbs and other function words were also excluded. A similar script was used for Old English. These scripts were unable to find the English translation or the inherent polarity of the modified phrase, as this information was not directly included in the corpora. For adverbs with a small number of attestations, this information was collected manually, and faulty information was corrected when necessary. For those with a large number of attestations, this was done only for entries with a pair frequency of 5 or greater for Middle Low German and Middle High German combined. For entries from Middle Low German texts of which the corpus contains multiple different versions, only the occurrence from the oldest version was included in the analysis, unless either the adverb or the modified phrase differed between versions.Footnote 24 In the latter case, the occurrences from both versions were included.

Afterwards, the usage of each of the adverbs listed in table 4 was analyzed, and cognates between Old Saxon and Middle Low German were compared. The different adverbs from the two languages are listed in section 4. The analysis was based on a total of 1,284 database entries (132 for Old Saxon and 1,152 for Middle Low German). Additional comparisons were made with other Germanic languages, most notably High German, English, and Dutch when appropriate. When possible, the adverbs’ histories were also outlined.

4. Results

4.1. Adverbs of High Degree

Table 5 shows the distribution of categories for the adverbs of high degree in Old Saxon, and table 6 does the same for Middle Low German, which is necessary in order to explore potential differences in usage between the two languages. These adverbs are discussed individually below.

Table 5. The distribution of categories for the adverbs of high degree in Old Saxon.

Table 6. The distribution of categories for the annotated adverbs of high degree in Middle Low German.

The most commonly used Old Saxon adverb of high degree is swîðo ‘very’, which resembles Old English swîþe, as described in section 2.4. Old Frisian also uses swîthe, though it is relatively infrequent compared to other adverbs of high degree, based on data from the Corpus Old Frisian (Van de Poel 2019).Footnote 25 At the same time, its expected Old High German cognate + swindo is not attested, and the same holds true for Middle High German. It is also not found in Middle Dutch as an adverb of degree, but an isolated example is found in the Old Low Franconian Wachtendonck Psalter in the form suitho (Quak Reference Quak1981:167), which also displays a loss of the etymological + -n-.Footnote 26 Its Gothic cognate, swinþs ‘strong’, is exclusively attested as an adjective. It is therefore likely that usage of this adverb is a feature of North Sea Germanic.

As is shown in table 5, swîðo is most often attested modifying adjectives, adverbs, verbs, prepositional phrases, and participles. Méndez-Naya (Reference Méndez-Naya2003) documented the usage of swîþe in Old and Middle English, and the distribution of categories is similar to Old Saxon. In total, Old and Middle English swîþe modifies adjectives and adverbs 708 times, verbs 318 times, and participles 105 times (Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003:380). This similarity in usage is illustrated in 5; 5a comes from the Heliand and 5b from the Old English History of the Holy Rood-Tree.

(5)

All attestations of Old Saxon swîðo modifying prepositional phrases occur as part of the fixed collocation swîðo an sorgun ‘very much in sorrows’, which appears once in Genesis and eleven times in the Heliand. While this usage is not listed by Méndez-Naya, instances can be found in the Old English corpora that show swîþe modifying similar prepositional phrases, as illustrated in 6, in which the example from the Heliand in 6a can be compared with the example from Ælfric’s Catholic Homily for Martinmas in 6b.

(6)

There are two instances in which swîðo appears in the comparative, and both instances are with verbs: farwirkian ‘to sin’ and haldan ‘to hold’.

Unlike swîðo in Old Saxon, swinde (with restored -n-) is quite rare in Middle Low German. The corpus contains two instances of it being used adverbially, and these are shown in example 7.

(7)

However, in both cases it is unlikely that a degree meaning was intended. Binden ‘to tie up’ is not clearly gradable, and so a manner adverbial reading could be assumed: ‘to tie up tightly’. In the case of schrîen ‘to scream’, one might entertain the translation ‘very loudly’, which is essentially equivalent to ‘scream very strongly’. In both cases, swinde modifies a verb, which is less common in Old Saxon. Clearer examples are given in Schiller & Lüben Reference Schiller and Lüben1878 (Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch, s.v. swinde), as they list sentences that contain swinde vast ‘very firm’, swynde grot ‘very big’, and swynde vruchten ‘to fear very much’. However, these are not found in the corpus, which indicates that it was a marginal adverb of high degree at best.

A peculiar adverb of high degree in Old Saxon is tulgo ‘very’, which is found only with adjectives and adverbs. It is most likely a cognate of Gothic tulgus ‘firm’. This adverb is also attested once in Mercian Old English in the form tulge, along with adjectival variants such as tylig and tylg ‘eager’, and it is thus considered a Mercian archaism (Vleeskruyer Reference Vleeskruyer1953:33). Tulgo is found seven times in the Heliand when combining M and C, though there are three instances in which tulgo is used in place of swîðo in S, as was first reported by Korhammer (Reference Korhammer1980:87). Compare the following lines from Bischoff’s (1979) transcription of Heliand S with the diplomatic edition based on M and C (Behaghel & Taeger Reference Behaghel and Taeger1996) in 8.

(8)

The data in 8 imply that the two may have been perceived as interchangeable at least by the scribe of S. No trace of this adverb is found in Middle Low German.

According to Fritz (Reference Fritz2006:144), Old Saxon filu ‘very, much’ is one of the oldest adverbs of high degree, along with hardo. However, only filu is found in Gothic where it is used as a gloss for Greek sphódra ‘very’ (Carlson Reference Carlson2012:297) or for lī́ān ‘very’, as in sleidjái filu ‘very fierce’. It is also frequently found with máis ‘more’ in Gothic (10x), based on data from Project Wulfila (2021). This finding could indicate that the tendency of filu to modify comparatives in later languages was generalized from this collocation. It is also used in Old English in the form fela, often as an intensifying prefix (see Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2021). It is found 15 times in the corpora, but never as an independent adverb of degree and never with comparatives; likewise, fēle remains rare in the Middle English period (Mustanoja & Van Gelderen 2016:319). As mentioned in section 2.4, compared to other adverbs of high degree, this adverb is especially frequent in Old High German, where it is attested 393 times.

In Old Saxon, filu is notably less common than swîðo, as it is found only 14 times, and it commonly modifies verbs. In these instances, it is often difficult to separate the usage of filu as an adverb of degree from its usage as an adverb of frequency meaning ‘much’, and the translation provided by the corpus was relied upon. For example, it is unclear if filu gornoda should be translated as ‘strongly mourned’ or as ‘much mourned’. Examples in which filu modifies adjectives are clearer. In two such cases, filu is used as a prefix in the formation filuwîs ‘very wise’ as in Old English, and it occurs once as an independent adverb with the adjective langsam ‘long lasting, eternal’. All attestations are from the Heliand.

In Middle Low German, instances in which vēle modified mannich ‘many’ and mêr ‘more’ were excluded, because in these cases its meaning tends to be more quantificational. Unlike Old Saxon filu, vēle most commonly modifies adjectives in the annotated subset of the data. During the Middle Low German period, vēle also acquires another usage, namely, as a modifier of comparatives and related constructions, which is also found in Early Middle Dutch, for example. This would later become the specialized usage of this adverb (Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:222), as mentioned in section 2.4. Notably, Old High German filu also had this usage: It is attested with comparatives six times. In Middle Low German, vēle is not attested with comparatives until the first half of the 15th century, which is different from both Dutch and High German, though it is only scarcely attested before this period. It should be noted that vēle never becomes as dominant relative to its competitors as its High German counterpart (see table 2 for details on High German).

As also pointed out in Visser & Hoeksema (Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:222), sêro ‘sorely, very’ is a fairly marginal adverb in Old Saxon, being attested only four times. The clearest example is with the adjective bitengi ‘oppressive’. In other examples, it appears with the participle antgoldan ‘atoned’ and with the verbs hreuwan ‘to mourn’ (with the comparative sêrur) and biwôpian ‘to deplore’, and so its status as an adverb of degree is ambiguous, as sêro could also be translated as ‘sorely’ in these instances. These examples suggest at least a strong association with negative words. According to Fritz (Reference Fritz2006:144), the usage of sêro as an adverb of high degree originated from phrases such as sêre wunt ‘sorely wounded’, and its meaning generalized as early as Middle High German; this exact collocation was suggested by Fritz and is not attested in either Old Saxon or Old High German (sêro is found only four times in Old High German and only with verbs). It is not uncommon for adverbs of high degree to derive from negative words, in which case they show a preference for modifying negative words in the early stages of grammaticalization (Lorenz Reference Lorenz, Wischer and Diewald2002:144–145). A parallel example from Modern English is terribly, which predominantly combines with negative words, although combinations with positive words are still found (see Lorenz Reference Lorenz, Wischer and Diewald2002:144–145). By contrast, the Modern German successor to sêro, sehr ‘very’, can be used with any adjective to convey “half-hearted intensification” (Claudi Reference Claudi2006:365). This indicates that it is at a further stage of delexicalization than English terribly and so has completely lost its semantic value.

Out of all instances of sêre in the Middle Low German corpus, 432 were annotated. Already in 13th-century Middle Low German, sêre was the most dominant adverb of high degree. As outlined in section 2.4, its Middle High German counterpart shows a rapid increase in use beginning in the 12th century, though it never becomes as dominant there as it does in Middle Low German. In fact, the frequency of sêre in Middle Low German is closer to the frequency of its counterpart in 13th-century Middle Dutch than in High German: It is attested 783 times against 423 attestations of harde and only 144 attestations of vēle (Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:212). This increase in the usage of sêre can thus be considered a characteristic of the Middle Germanic languages on the continent, though it is more prominent in Middle Low German and Middle Dutch than in Middle High German. The distribution of categories generally resembles Early Middle Dutch (see Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:212), where there is also a clear preference for verbs, adjectives, and participles. As in Old Saxon, sêre has a preference for negative phrases, in which it appears 240 times.

In Old Saxon, hardo ‘very, firmly’ is attested modifying the same categories as filu and sêro, but it is also found with the prepositional phrases an thînumu hugi ‘in your mind’ (2x) and umbi is herte ‘around his heart’ (1x). Like sêro, hardo prefers negative phrases (eight out of twelve attestations), which could be explained by the fact that the adjective hard, from which it is derived, can also have negative meaning ‘difficult’ (Behaghel & Taeger Reference Behaghel and Taeger1996:274).

The distribution of harde in Middle Low German differs from hardo in Old Saxon, as it exclusively modifies adjectives and adverbs in the former. Its use is also different in Middle Dutch, where it also combines predominantly with adjectives, although it is still occasionally attested with verbs there (Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:212), and it can still modify verbs in both Old and Middle High German as well. In Middle High German, the most common verbs modified by harte are erkomen ‘to frighten’ and vürhten ‘to fear’, both of which are also found with harto in Old High German as irqueman ‘to be astonished’ and forhten ‘to fear’. Furthermore, its preference for inherent polarity in Middle Low German is inverted compared to Old Saxon, as harde is attested with positive phrases 40 times out of 43. It also prefers positive phrases in Middle Dutch (Visser & Hoeksema Reference Visser and Hoeksema2022:212) and Old High German.

Middle Low German uses grôtlîk ‘greatly’ as a verb modifier. It appears for the first time in the 15th century, while its counterparts in Middle Dutch and Middle High German, grôtelike and grôzlîche, respectively, are both found as early as the 13th century. Another adverb of high degree that emerges during the Middle Low German period is ûtermâte ‘exceedingly’ (compare Middle Dutch ûtermâten ‘exceedingly’ and Middle High German ûzer mâze ‘exceedingly’). When viewed diachronically, it is first attested three times in the second half of the 13th century and then disappears; then it reappears in the 15th century and remains in use throughout the 16th century. It is the only adverb of degree analyzed here that displays such a pattern.

4.2. Absolute Degree

Similar to tables 5 and 6, table 7 displays the distribution of categories for the adverbs of absolute degree in Middle Low German, and these are discussed below, along with Old Saxon garo ‘fully’.

Table 7. The distribution of categories for the adverbs of absolute degree in Middle Low German.

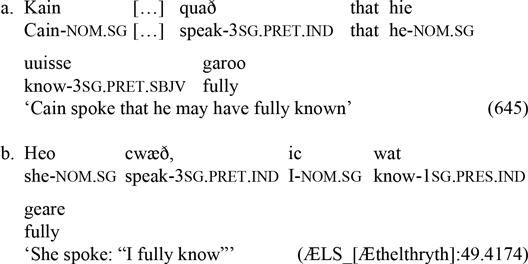

The only well-attested adverb of absolute degree in Old Saxon is garo, and it is exclusively used to modify verbs of perception. It is attested once in Genesis and eight times in the Heliand, and only with the verbs witan ‘to know’ (7x), kunnan ‘to known’ (1x), and afsebbian ‘to notice’ (1x). A similar usage is also observed for its Old English cognate ġearwe: Out of 87 attestations in both Old English corpora combined, the three most commonly modified words are witan ‘to know’ (57x), cunnan ‘to know’ (18x), and ġemunan ‘to remember’ (3x). In contrast, such constructions with perception verbs are not found in Old High German. The similarity between Old Saxon and Old English is shown in example 9: 9a comes from Genesis and 9b from Ælfric’s Lives of Saints.

(9)

The Old Saxon usage of garo is not continued in Middle Low German, as it is never found with the three verbs mentioned above. Instead, it is mainly found with adjectives and adverbs, as shown in table 7.Footnote 28 The most commonly modified adjectives and adverbs are open-scale ones: wol ‘well’ (39x), balde ‘boldly’ (18x), grôt ‘big’ (15x), which are generally incompatible with absolute modifiers (Kennedy & McNally Reference Kennedy and McNally2005). This distribution of garo suggests that it may be closer to an adverb of high degree instead. A similar pattern can be observed in Middle High German, when it is used as an adjective modifier.Footnote 29 Due to the reduction of unstressed vowels, the Middle Low German adverb has become identical in form with its associated adjective gār ‘ready’ derived from Old Saxon garu ‘ready’, though it seems unlikely that its new usage also comes from Old Saxon. Its usage differs from Middle English yāre ‘fully’, whose usage continues from Old English and which also acquired the meaning ‘readily, eagerly’, according to the Middle English Dictionary (med 2001, s.v. yāre adv.)—likely from the associated adjective meaning ‘ready’ that had the same form (med 2001, s.v. yāre adj.). A usage of yāre as an adjective modifier is not listed by the med (2001, s.v. yāre adv.).

One Middle Low German adverb that can unequivocally be attributed to High German influence is gans ‘fully’, as its final consonant is affected by the High German Consonant Shift. This word apparently spread from High German to Low German, Dutch, and Frisian, and then from Low German to North Germanic (Kroonen Reference Kroonen2013, s.v. +ganta-). It is first attested in South Markish in the second half of the 14th century, but it is mainly used in the 15th and 16th centuries. A selection was annotated. While its lexical meaning ‘whole’ implies gans is an adverb of absolute degree, the most frequently modified words are open-scale adverbs, such as sêre ‘very’, wol ‘well’, gērne ‘eagerly’. This is a pattern similar to gār, though gans is less frequent. Perhaps its usage is similar to ganz in Modern German, where it functions as an adverb of high degree when modifying negative adjectives and as one of low degree when modifying positive ones (Claudi Reference Claudi2006:366).

5. Discussion

Overall, the system of degree adverbs in Old Saxon appears to be quite similar to the one in Old English. This applies both to the type of adverbs that are used and how they are used, as shown in section 4. In contrast, the systems of Old Saxon and Middle Low German differ substantially: The latter is more similar to Dutch and High German than the former, which is also largely true when it comes to the features discussed in section 2.3. As such, the behavior of adverbs of degree can confidently be added to the list of features that set Middle Low German apart from Old Saxon. The differences between the systems of degree adverbs in the two languages are also far greater than between the systems in Old and Middle High German or even in Old and Middle English. In fact, there is comparatively little that unites them, with the possible exception of the early usage of sêro in Old Saxon. Particularly, the near-complete disappearance of the most frequent high degree modifier swîðo is unusual, as the most frequent high degree modifier in High German, filu/vile ‘much, very’, remains dominant throughout the medieval period, as shown in table 2. Such radical decline of swîðo is not paralleled in Old English, where swîþe remains in use for a longer period of time, though it would eventually decline there as well, as outlined in section 2.4.

The question remains how these discrepancies can be best accounted for. As stated earlier, this paper evaluates two main hypotheses, based on the data from degree adverbs: The apparent lack of continuity between Old Saxon and Middle Low German is due either to prolonged influence from High German or to the artificiality of the Old Saxon literary language. In the following sections, each hypothesis is examined in light of the data presented so far.

5.1. Hypothesis 1: High German Influence

According to the first hypothesis, the apparent lack of continuity between the systems of degree adverbs in Old Saxon and Middle Low German is due to High German influence on the latter. The main argument in favor of this hypothesis comes from the erosion of North Sea Germanic features in Middle Low German. Its system of degree adverbs broadly shows convergence with High German, and these changes fit the broader trend of eliminating North Sea Germanic features, as discussed in section 2.3. It is notable that the Old Saxon adverbs swîðo and tulgo, both of which likely belong to the North Sea Germanic lexicon and do not have equivalents in High German or most varieties of Dutch, are the ones that declined the most. Perhaps their decline can be attributed to convergence in the form of dialect leveling, as they could have been perceived as salient dialect markers and therefore avoided (Kerswill & Williams Reference Kerswill, Williams, Mari and Esch2011, Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986:11). However, further research on adverbs of degree in a contact situation would have to be undertaken to evaluate how likely it is for a high frequency adverb such as swîðo to nearly completely disappear.

To what extent language contact played a role in the decline of swîþe in Old English is also unclear. Méndez-Naya (Reference Méndez-Naya2003:389) gives exclusively language-internal reasons: She argues that the main reason for its decline is a loss of expressivity over time. At the same time, the distribution of Middle Low German adverbs that are present in both Old High German and Old Saxon is more akin to the one in High German. This applies to garo/gār, filu/vēle, and hardo/harde, as shown in section 4. The former two show a movement away from a distribution akin to Old English and toward High German. The change in usage of hardo/harde could also be due to convergence, but it could also signal more semantic bleaching and thus grammaticalization, as its negative lexical meaning is further eroded (Klein Reference Klein1998:25–26, Hopper & Traugott 2003:104).

While no research to date has specifically addressed the effect of language contact on the distribution of adverbs of degree, it seems plausible that cognates can influence one another in a contact situation. This is illustrated by the fact that Low German appears to undergo the same changes at various points in time as High German, such as the rise of sêro/sêre or the development of ûtermâte, grôtlîk, and gans. The former must have occurred during the attestation gap between the composition of Genesis and the beginning of the Middle Low German period, while the latter occurred later. It is notable that only gans can be considered a straightforward borrowing, as it is the only one that displays the High German Consonant Shift, perhaps owing to the fact that it did not have a cognate in Low German before this period.

There are a number of issues with the High German influence hypothesis. One issue, for example, concerns the change in usage of garo/gār. As described in section 4.2, its pattern of use in Old Saxon changes in Middle Low German in a way that runs counter to the usual grammaticalization pattern: From modifying verbs of perception, it moves to modifying adjectives and adverbs, whereas normally adverbs of degree have a tendency toward specialization (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:18). If one assumes direct continuity, this development is puzzling: It seems as if the context of use of this adverb has changed completely, and there is no trace left of its older function. It is currently unclear to what extent such a significant change can be attributed to language contact, and further research on this topic may be required to make a final judgment.

Another challenge for the High German influence hypothesis is posed by the dominance of sêre in 13th-century Middle Low German (see discussion in section 4.1). In this regard, sêre much more resembles its counterpart in Middle Dutch than in Middle High German. This, in turn, suggests convergence of Middle Low German with Dutch and not just with High German. One implication of interpreting this convergence solely based on language contact is that the system of adverbs of degree had to be quite stable between the departure of the Anglo-Saxons and the composition of the Heliand: The similarity of the system of degree adverbs in the Heliand and Genesis to the one in Old English suggests that relatively little change must have occurred during this early period (as opposed to fairly significant changes that must have occurred later). Such a state of the system, however, would be more in line with the hypothesis of early linguistic stability (Krogh Reference Krogh1996:403–404, Krogh Reference Krogh2013, Versloot & Adamczyk Reference Versloot, Adamczyk and Hines2017:126) than with early dialect mixing (Wolff Reference Wolff1934:154, Stiles Reference Stiles, Volkert, Alastair and Wilts1995:202, Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller and Jan2007:32, Peters Reference Peters2012:447, Stiles Reference Stiles2013:20).

Finally, it is unclear to what extent High German influenced other parts of the Low German lexicon during the gap between the time when Genesis was composed and the Middle Low German period. Although during later periods, Low German showed convergence with High German in the domain of grammatical words (see Peters Reference Peters1995), it is currently unclear to what extent this happened during the early period.

Despite the influence that High German has had on Low German, it is clear that this language contact was fairly one-sided: Peters (Reference Peters1999:167, 170) notes that the bulk of Low German vocabulary in Modern Standard German dates from the time after High German had replaced Low German as the main written language, and that the influence of Low German on High German was marginal before this period. The high level of stability in the High German adverbs of degree also attests to this limited influence and shows that language contact need not always lead to change in the system of adverbs of degree.

Thus, the High German influence hypothesis is unable to capture the apparent lack of continuity in the system of degree adverbs between Old Saxon and Middle Low German. In the next section, I examine the grapholect hypothesis in light of the same data and show that it can better account for the differences between the two languages.

5.2 Hypothesis 2: Old Saxon as an Artificial Grapholect

According to the grapholect hypothesis, the apparent lack of continuity between Old Saxon and Middle Low German is due to the fact that literary Old Saxon never reflected a genuine spoken language (Collitz Reference Collitz1901, Rooth Reference Rooth1973, Doane Reference Doane1991:45–46). Instead, it was at least partially an imitation of Old English conventions, which explains why certain patterns of use are absent from Middle Low German. I argue that this hypothesis is better suited to account for the drastic differences between the two languages. For example, the extensive use of swîðo in both the Heliand and Genesis imitates an Old English convention rather than reflects its actual usage, which is why it is not found in Middle Low German.

This reasoning also applies to adverbs with different patterns of use in Old Saxon versus Middle Low German. For example, if the usage of Old Saxon garo and filu is an imitation of Old English, this would explain the different behavior of these adverbs in Middle Low German. The use of Old Saxon garo may have been modeled after Old English ġearwe (see discussion in section 4.2), which explains why Middle Low German gār exhibits a very different pattern of use. Similarly, Old Saxon filu never occurs with comparatives, unlike Middle Low German vēle. This contrast is explained if the use of filu imitated the use of Old English fela, which also never combined with comparatives (see discussion in section 4.1). In contrast, the use of this adverb with comparatives could reflect an early usage (as in Gothic) and not be a result of late convergence with High German.

The main argument against the grapholect hypothesis is that the Old Saxon system of degree adverbs does display unique features of its own that set it apart from Old English. One such feature is the usage of tulgo. While this adverb represents an isogloss between Old English and Old Saxon, it is far more restricted in the former, being attested only once, as mentioned in section 4.1. The fact that the scribe of Heliand S added additional instances of this adverb makes it less likely that this was a mere imitation of Old English, as these additions indicate that this adverb was likely a part of the scribe’s native dialect. Alternatively, one could assume influence from Frisian on the language of S. There are no attestations of this adverb in Old Frisian, but this is possibly due to the late attestation of the language (there are no major Old Frisian texts attested before the late 13th century), as Stiles (Reference Stiles, Volkert, Alastair and Wilts1995:209) considers it likely that it was used there as well, though this remains a speculation. Either way, tulgo is a relatively low-frequency adverb in Old Saxon and so it would be more likely to disappear than a high-frequency adverb, such as swîðo, especially if it was already a declining adverb.

Note that the adverb swîðo may also present a challenge for the grapholect hypothesis, as its usage in the Old Saxon texts differs somewhat from its usage in Old English. For example, the fixed collocation swîðo an sorgun ‘very much in sorrows’, which appears in both major Old Saxon texts, is particularly unusual, as it is not found in Old English, though swîðo does combine with other similar prepositional phrases (see example 6b). Furthermore, the fact that traces of this adverb remain in Middle Low German, as noted in section 4.1, also suggests that the usage of swîðo cannot have been wholly artificial, though its usage frequency in the Heliand and Genesis may have been inflated.

Despite those two examples, however, compared to the High German influence hypothesis, the grapholect hypothesis presents fewer serious issues, and so it more easily accounts for the changes in usage of adverbs such as garo/gār and the decline of swîðo. It is currently uncertain to what extent High German influence could have caused these changes. Also, the suggestion that the usage of tulgo may not have been strictly artificial does not necessarily pose a problem for the grapholect hypothesis, since it could have declined naturally. Regardless, both the larger presence of tulgo and the somewhat differing usage of swîðo require the additional assumption that not everything in the language of the Heliand is a strict imitation of Old English conventions, and that it still incorporated native Old Saxon elements.

It is also important to stress that if written Old Saxon were an artificial grapholect, this would not exclude the possibility of High German influence. In fact, this would suggest that the system of adverbs of degree in Old Saxon was closer to High German (and by extension to Middle Low German) than what is reflected in the language of the Heliand, which would be in line with the hypothesis of early dialect mixing (Wolff Reference Wolff1934:154, Stiles Reference Stiles, Volkert, Alastair and Wilts1995:202, Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller and Jan2007:32, Peters Reference Peters2012:447, Stiles Reference Stiles2013:20). Under this view, High German could still have contributed to the decline of adverbs such as tulgo. Ultimately, more work on adverbs of degree in a contact situation is required to evaluate how likely it is that dialect contact could have caused the stark differences between Old Saxon and Middle Low German. In the meantime, the possibility that the system reflects an artificial poetic register should not be discarded.