1. Introduction

Pronominal adverbs in German consist of one of the adverbs da ‘there’, wo ‘where’, or hier ‘here’ as first element and a preposition as second element (for example, davor ‘before’, danach ‘thereafter’, worauf ‘whereon’, womit ‘wherewith’, hierunter ‘hereunder’, hiermit ‘herewith’, etc.). Between the first and the second element, /r/ can occur (as in, for example, darauf ‘thereon’, worunter ‘whereunder’), which can be seen as an epenthetic consonant from a synchronic point of view.

Pronominal adverbs (PAs) pose some questions concerning their internal structure because they contain an adverb which occurs to the left of the preposition. This has been explained by the replacement of an NP-pronoun by da, hier, or wo and a movement of this element in front of the preposition.

It is the aim of this article to present an alternative account and show that a diachronic perspective can shed a different light on the characteristics of PAs, which exhibit a number of properties that grammaticalization theory can account for. A special focus will be on the nature of the second element in PAs. It will be argued that, from a diachronic point of view, the internal structure of PAs can be explained by a process of univerbation of adverbial phrases expressing spatial deixis. It will be argued that PAs originate from two separate local adverbs forming an adverbial phrase. The univerbation of these two elements is accompanied by several processes generally associated with grammaticalization. There is a semantic bleaching of the spatial meaning, a concomitant development of metaphorical meanings and a strengthening of textual functions of PAs, a phonological reduction of the first element, as well as a loss of syntactic separability of the two elements in the standard variety. From a diachronic point of view, the separate occurrence of the two elements of PAs is a remnant of earlier stages which is preserved mainly in colloquial language and dialects in northern Germany. The phonological reduction of PAs can be compensated for by a doubling of the first elements, thereby showing characteristics of a grammaticalization cycle. Moreover, some reduced forms can no longer be replaced by full forms in certain contexts. This is a split which is typical of grammaticalization processes.

First, the class of German PAs will be characterized in section 2. In section 3, movement analyses of PAs for Dutch and German are reviewed and some of their problems and shortcomings will be pointed out. Section 4 investigates the nature of the second elements of PAs. Section 5 shows that the order of elements and the elements involved in PAs naturally follow from a process of univerbation of the adverbial phrases that the PAs originate from. The concomitant processes typical of grammaticalization are pointed out in section 6, which comprise semantic bleaching, phonological erosion, as well as a decreasing syntactic separability. Section 7 shows that further reduction may lead to splits between full and reduced forms which are typical of grammaticalization. In section 8, it is argued that doubling of the first element is a result of a weakening of this element. Weakening and subsequent strengthening constitute a grammaticalization cycle. The main conclusions are summarized in section 9.

2. Pronominal Adverbs and Their Variants

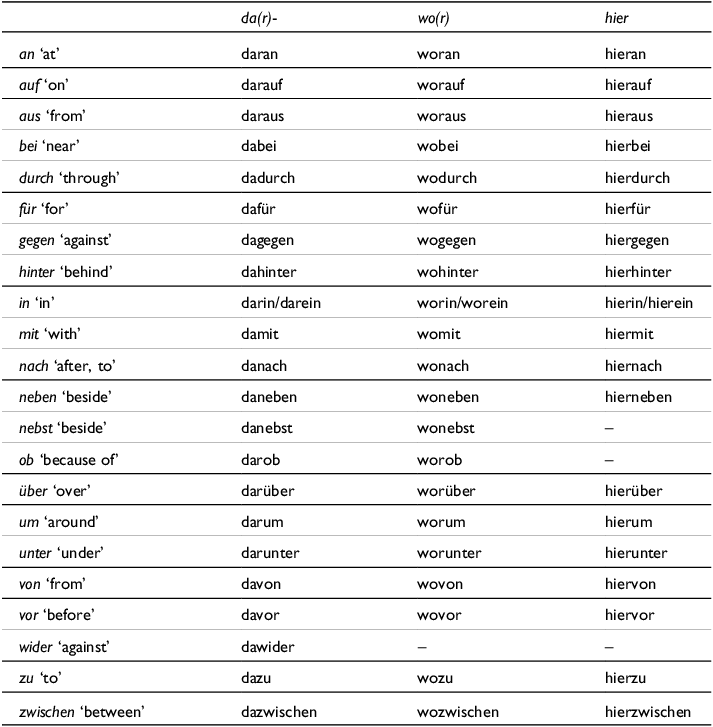

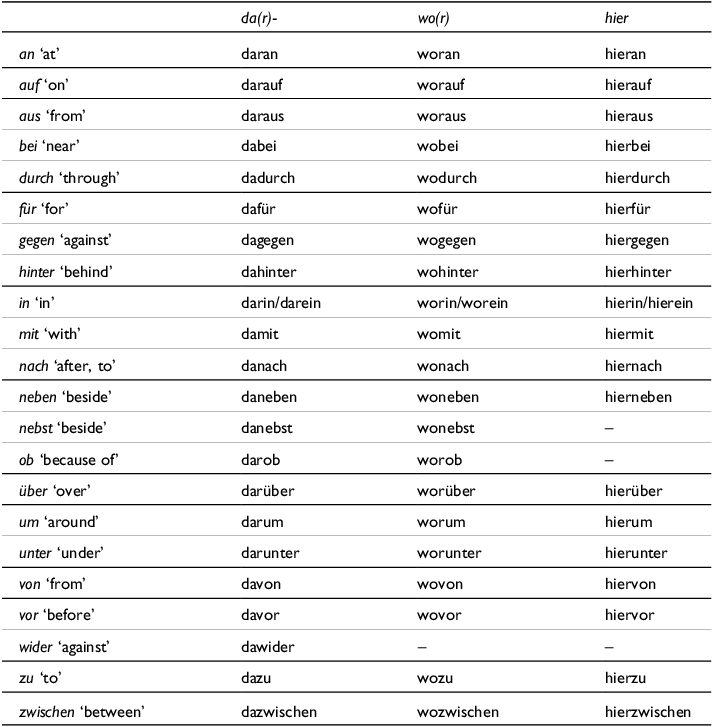

PAs in German contain the adverbs da, wo, and hier (‘there’, ‘where’, and ‘here’) as the first element and an element which is a preposition, as in Table 1. The prepositions in PAs are so-called “primary prepositions” which form a closed class of very old prepositions (cf. Table 1).Footnote 1

Table 1. Pronominal adverbs in German

The first element is often called an R-pronoun, following van Riemsdjik (Reference Riemsdijk1978), who coined the term “because they all have an r-sound in their phonological form (eR, daaR, hieR, waaR)”, as Zwarts (Reference Zwarts1997: 1092) states with reference to Dutch. German PAs are also called prepositional adverbs (“Präpositionaladverbien”) because the second element is a preposition as a free lexeme. The term pronominal adverb refers to the function of PAs as proforms and will be used here, since it is well established.

Like pronouns, PAs have anaphoric and cataphoric functions. In contrast to pronouns, which substitute nominal phrases, PAs are proforms for prepositional phrases (PPs). They are adverbs since they are uninflected and can have adverbial functions. Like other adverbs in German, they can occur in the so-called pre-field, in the first position of verb-second clauses.

PAs are used as proforms for full PPs, but there are several restrictions regarding which kind of PPs they may substitute. They can only be used for inanimate referents (see Helbig Reference Helbig1974:133).Footnote 2

Moreover, they often cannot be substituted for many adverbial PPs (see Helbig Reference Helbig1974:133, Krause Reference Krause2007):

The reason for this may be that adverbial PPs can be substituted by adverbs like dort ‘there, dann ‘then’, damals ‘at that time’, etc. This is not possible for PPs in the function of a prepositional object, which can only be substituted by PAs or, in the case of animate referents, by the respective preposition plus a pronoun.

PAs are a common phenomenon of West Germanic languages. They occur in German, Dutch, and Frisian, as well as in English.Footnote 3 However, they are far more frequent in German than in English. Whereas in English PAs (thereby, thereupon, thereout, thereinto, therein, hereby, whereby, etc.) have a somewhat archaic and formal touch and are sometimes seen to be characteristic of legal language, in German they are stylistically neutral and can fulfill more functions than in English. Besides being a proform of PPs, they also occur as correlates of subordinate clauses (adverbial clauses and sentential prepositional objects), which is not the case in English.

The PAs with da are by far the most frequent PAs and have received the most attention. The PAs with wo as first element are used as interrogative as well as relative adverbs. They may occur in questions if it is presupposed that the substituted noun does not refer to a person (Helbig Reference Helbig1974:133). In these cases, the use of a preposition with an NP-pronoun is considered to be colloquial:

PAs with hier are sometimes seen as stylistic variants of da-PAs and are far more restricted in their use. Footnote 4

Some PAs are also sentence connectors (“conjunctional adverbs”) which establish various relations to the preceding sentence, such as causal, conditional, concessive, and adversative relations. In contrast to conjunctions, they can occur in the pre-field and they do not trigger verb-final position. Sometimes it is not possible to distinguish clearly between a pronominal use (which may be substituted by a full PP) and the conjunctional use relating to the preceding sentence. In (5) darum establishes a causal relationship between the two clauses and may not be replaced by a full PP.

What makes PAs especially interesting are their variants: on the one hand a splitting of the two components, which is often seen as a form of preposition stranding (6a), and on the other hand a doubling of the first part which may occur adjacent to the PA or at a distance (6b and c).

As will be shown in sections 6.3 and 8, a diachronic perspective can provide an explanation for these phenomena.

3. Movement Analyses

Within generative grammar, a number of analyses have been proposed which derive PAs by movement of a pronoun out of the complement position of a preposition to the left of the preposition. Since some of the influential analyses have been developed for Dutch, we will briefly review them here. This is not the place for an in-depth description of the analyses for Dutch, but some basic assumptions will be pointed out. Subsequently, movement analyses for German PAs will be dealt with in more detail.

3.1 Pronominal Adverbs in Dutch

In his treatment of PAs, van Riemsdijk (Reference Riemsdijk1978) distinguishes neuter pronouns and their R-variants. The neuter pronouns are et ‘it’, dat ‘that’, dit ‘this’, wat ‘what’, iets ‘something’, niets ‘nothing’, alles ‘everything’. The R-pronouns comprise er ‘there’, daar ‘there’, hier ‘here’, waar ‘where’, ergens ‘somewhere’, nergens ‘nowhere’, overal ‘everywhere’, and bear a feature [-human]. Van Riemsdijk proposes a filter which prohibits neuter pronouns from appearing in the complement positions of prepositions (*op het). A transformational rule turns neuter pronouns into R-pronouns which can escape this filter by moving into a special specifier position. This position also functions as an escape hatch for moving the R-pronoun out of the PP (er op).

The R-pronouns may occur within the PP in a specifier position of the preposition (7a) or move out of it (7b).

The fact that not all prepositions allow this movement is explained by the presence or absence of this special specifier position.

Some shortcomings of this approach have been pointed out by Bennis (Reference Bennis1986). One is that the correlation between [-human] pronouns and R-movement is not as strong as suggested by van Riemsdjik, since for example neuter pronouns like alles ‘everything’ or niets ‘nothing’ as well as dat ‘that’ may occur to the right of prepositions. Moreover, R-pronouns are not automatically [-human] but may refer to persons in certain instances.

What distinguishes prepositions which allow this kind of movement in Dutch from those that do not allow it has been a matter of some debate. Koopman (Reference Koopman1993) suggests that those allowing it are spatial prepositions and that the R-pronouns are checked in the specifier position of a functional head, the PlaceP:

Zwarts (Reference Zwarts1997) points out that there are clear counterexamples of prepositions with spatial meanings but no R-pronouns, like beneden ‘beneath’, benoorden ‘north of’, beoosten ‘east of’, bewesten ‘west of’, bezijden ‘beside’, bezuiden ‘south of’, halverwege ‘halfway’, nabij ‘near’, richting ‘in the direction of’, rond ‘round’, te ‘at’, via ‘via’. He also proposes a movement analysis and starts from the observation that only certain prepositions, which he calls type A prepositions, allow for this kind of preposition stranding. Whereas type A prepositions are “real prepositions,” that is simple lexemes, type B prepositions are more complex and do not allow for the kind of movement by R-pronouns. What Zwarts calls type A prepositions are essentially “primary prepositions,” whereas type B are secondary prepositions which are more recent and derived from elements of other word classes (see, for example, Diewald Reference Diewald1997).

Zwarts assigns the type B prepositions the following structure with a lexical head of unspecified category:

This complexity distinguishes type B prepositions from type A prepositions that are simply Ps. The complexity can be due to several reasons: type B prepositions may be derived from other word classes like nouns and may be due to univerbation or conversion.

Additionally, there are prepositions that are derived from present and passive participles like betreffende (‘concerning’, from betreffen ‘concern’), ongeacht (‘regardless’, from achten ‘respect’). Also borrowed prepositions are counted among type B prepositions.

To sum up briefly: the analyses sketched here for PAs in Dutch assume that PAs involve movement of a pronoun out of the complement position of the preposition into a specifier position or a position outside the PP. Moreover, these analyses also try to explain why an NP-pronoun is substituted by an R-pronoun and why only R-pronouns can undergo this movement.

3.2 German Pronominal Adverbs

For German, several authors analyze PAs as being derived by movement of an R-pronoun. Gallmann (Reference Gallmann1997) suggests that da may be either incorporated into the preposition (11a) or moved to the specifier of the preposition (11b).

The structure in (11a) contains a clitic which may be further reduced (d-r) and provides the basis for a doubling of da, which will be discussed in section 8. In (11b) the pronoun projects to a phrase that can be moved. This is the basis for preposition stranding, which will be discussed in section 6.3. Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2002) agrees with the main points of this analysis but objects that it cannot be extended to PAs with wo, which cannot move and can only occur incorporated into the preposition.

Müller (Reference Müller2000) treats PAs in German as a repair phenomenon within an optimality theoretical framework. This theory starts from the basic assumption that there are several alternatives for realizing an expression. From an input (in the case of syntax essentially a list of lexemes) several output candidates are produced by a generative component of grammar. These candidates are evaluated in relation to a number of universal constraints that are ranked language-specifically and may be violated. The optimal candidate violates the fewest high-ranking constraints. Repair phenomena arise when very high-ranking constraints necessitate the violation of faithfulness constraintsFootnote 5 in the optimal output, which can only be a last resort in order to fulfill even higher-ranking constraints (Müller Reference Müller2000:148). Among these faithfulness constraints is ECON, an economy principle stating that syntactic movement is to be avoided, and SEL, which means that lexical selectional restrictions of the input must be fulfilled in the output.

PAs are conceived of as a repair phenomenon that solves two conflicting tendencies which Müller (Reference Müller2000:139) refers to as the “Wackernagel-Ross-dilemma.” Unstressed pronouns occur in the so-called Wackernagel position at the beginning of the middle field after the left sentence bracket, which is a position for unstressed elements (PRON-KRIT constraint). According to a constraint going back to Ross (Reference Ross1967), an element which is assigned a case by a preposition may not be moved out of the PP (PP-BAR constraint). The formation of PAs resolves this conflict because they contain an R-pronoun which has no case and as a result is not subject to PP-BAR nor to PRON-KRIT. As Müller states, the dilemma can be solved in this way, albeit at a cost: SEL is violated since the R-pronouns do not fulfill the selectional restrictions of the prepositions involved. To give an example, the candidate in (12a) with a preposition and pronoun violates PRON-KRIT, and the candidate in (12b) with a pronoun in the Wackernagel position violates PP-BAR. Both violations are avoided by the candidate with the PA in (12c):

A catch-all term like da, an “Allerweltsproform” as Altmann (Reference Altmann1981) has called it, is assumed to be suitable for this repair strategy, because it is flexible in its functions. We will come back to this assumption in the next section. Footnote 6

For the movement of da, Müller considers two different explanations. One is a morphological principle operating word-internally. By moving da into the first position, the status of PAs as PPs is preserved due to the right-hand head rule. The other explanation he considers is that da has to move because it does not fulfill the selectional restriction of the preposition. However, both explanations are not convincing. As far as the formation of adverbs is concerned, the right-hand head rule is often violated (see also the next section). Moreover, the syntactic explanation does not take into account that adverbs may occur as complements to prepositions, even though they do not fulfill the case requirements of the preposition.

The tendency for pronouns to occur in the Wackernagel position is strongest for reduced pronouns like es, weaker for unstressed pronouns referring to inanimate objects, and weaker yet for unaccented pronouns referring to animate referents. It is weakest for stressed pronouns (PRON-KRIT). Müller proposes the following hierarchy of constraints:

Whether a PA can occur instead of a preposition plus a pronoun depends on whether SEL is lower, on a par, or ranks higher in the hierarchy of constraints. This hierarchy predicts that, in the case of stressed pronouns and pronouns referring to animates, the selectional restrictions of the preposition have to be fulfilled. As a result, the formation of PAs is impossible in these cases. Because the constraint for unaccented pronouns referring to inanimates is on a par with SEL, the formation of PAs is optional. With es as the complement of a preposition the tendency is so strong that it ranks higher than SEL. In this case, the formation of PAs is obligatory.

This is an optimality-theoretic reconstruction of the conditions for the use of PAs in German. It was already pointed out above that PAs cannot be proforms for PPs referring to animates—only for inanimate referents. Müller follows Helbig’s (Reference Helbig1974) view that es cannot occur as a complement of a preposition and the formation of a PA would be obligatory in these cases. This assumption is not valid, however, as the following examples from corpora show:

This shows that, as in Dutch, neuter pronouns are not completely excluded from appearing to the right of prepositions, not even the obligatorily unstressed pronoun es.

According to Müller, the differences between English and German related to PAs are explained by a different ranking of constraints. While PAs occur in Old High German (OHG) as well as in Old English, no new formations can be found in Middle English or in subsequent stages. Müller’s explanation for this is that the Wackernagel position disappeared in English but did not in German. But then the question arises whether the time when PAs were still formed in the two languages differs much. In English, the formation of PAs ends in the fourteenth century, since no preposition formed after the beginning of that century occurs in PAs (see Müller Reference Müller2000:173). But, as will be shown in the next section, also in German PAs are formed only with primary prepositions which existed already in OHG. Therefore, it is doubtful whether the disappearance of the Wackernagel position in English is the reason for the restricted use and stylistic markedness of PAs in English compared with German. PAs are used more frequently in German and are stylistically more neutral because they occur in a number of functions that they do not have in English. Moreover, in English preposition stranding is much more common in contexts in which Standard German uses PAs (see section 7.3). Therefore, within an optimality-theoretical framework, it can be assumed that in German the PP-BAR constraint is ranked higher than in English.

In sum, the analyses discussed here derive PAs from PPs by movement of an R-pronoun out of the complement position of the preposition. These movement analyses face several problems. They cannot provide a plausible reason for the movement since neuter pronouns as well as adverbs may appear as complements of prepositions. And they cannot give a reasonable explanation for why an NP-pronoun should be replaced by an R-pronoun. Additionally, the assumed movement of the pronominal part of PAs has the drawback that it has not taken place during the development of German.

In the next section, I will argue that a movement account does not consider a number of facts which can give a plausible explanation for the occurrence of da, hier, and wo as first elements of PAs. It will be shown how the diachronic development can shed new light on the structure of PAs and the nature of the second element.

4. Adverb or Preposition? The Nature of the Second Elements

Concerning their diachronic development, it is important to keep in mind that PAs occur in several West Germanic languages and therefore are a very old pattern.Footnote 7 In this context the question arises as to whether the second elements were prepositions in the period during which the formation of PAs occurred. Here it is important to note that primary prepositions can be traced back to adverbs in Proto-Indo-European.Footnote 8

Also from a synchronic point of view, the category of the second element is not uncontroversial. Krause (Reference Krause2007) raises the question as to why the second element in PAs is a preposition, considering the fact that there are formations with da, wo, and hier as first element and an adverb (daher ‘from there, therefore’, dahin ‘there’, woher ‘from where’, wohin ‘where to’, hierhin ‘here’ etc.) as a second element.

Wolfrum (Reference Wolfrum1970:304) pursues the question as to whether a preposition or an adverb occurred in OHG in combinations with thâr, thara. He observes that some of these elements could be either prepositions or adverbs, but a number of them were unambiguously adverbs, like înni ‘inside’, forna ‘before’, nidari ‘beneath’, obana ‘above’, ûf ‘up’, uze ‘outside’, and heim ‘homeward’.Footnote 9 Since none of the elements occurring after thâr, thara are unequivocally prepositions, he concludes that the elements forming the second part of what later became PAs must have been originally adverbs.

The adverbial forms are still in use in several dialects and some of them end on vowels, in contrast to the prepositions. As Große (Reference Große, Große, Lerchner and Schröder1992:113) points out, examples include the adverb miti as opposed to the preposition mit, or the adverb aba instead of the preposition ab, as well as the adverbial ana instead of the preposition an. Altmann (Reference Altmann1998:260) shows that the adverbial character of the second element can be clearly seen in a number of PAs in Middle Bavarian. In Standard German, however, there are no differences between these prepositions and their occurrences as adverbs. Their use as adverbs is not very common in present-day German, but they still occur in some phrasemes like ab und an ‘now and then’ or ab und zu ‘from time to time’, auf und ab ‘up and down’ or nach und nach ‘more and more’, and durch und durch ‘thoroughly’. Moreover, some of them occur with copula verbs in which case they are assumed to be adverbs, as in die Tür ist auf/zu ‘the door is open/shut, das Licht ist an/aus ‘the light is on/out’, or die Zeit ist um ‘time is up’ (see Hentschel Reference Hentschel2005). Also, the particles in particle verbs are very often adverbs (for example, an-kommen ‘to arrive’, aus-gehen ‘to go out’, auf-machen ‘to open’, mit-gehen ‘to accompany s.o.’).

Additionally, the PAs da-/wo-/hierein with -ein ‘in’ as second element show that the second element was an adverb since ein never occurred as a preposition. PAs with ein can be used with a directional meaning in somewhat archaic written language, while PAs with in may not be used with a directional meaning.

This shows that there is no need to assume that the second elements are prepositions with a case requirement which necessitates movement of an adverb not fulfilling this requirement. Moreover, there are some related word-formations and syntactic structures which render this explanation implausible. First, the same order occurs in lexemes with da, hier, and wo as a first element and an undisputed adverb as second element, as in dahin ‘there’, daher ‘from there, therefore’, hierher ‘here’, hierhin ‘here’, wohin ‘where to’, woher ‘where from’, also in drinnen ‘inside’, draußen ‘outside’, droben ‘up there’, drunten ‘down there’. There is no case requirement which could have been a reason for movement of da, hier, or wo into the first position in these word-formations. Second, and more importantly, the selectional restrictions proposed by Müller are valid neither in present-day German nor in earlier stages of German, since adverbs can occur as complements of prepositions in phrases like von da ‘from here’ nach oben ‘upwards’, vor morgen ‘before tomorrow’, nach links ‘to the left’, bis jetzt ‘until now’. This means that the suggested selectional restrictions cannot explain the order of elements in PAs.

In addition, an explanation by a word-internal operating principle like the right-hand head rule does not stand up to scrutiny, since the elements of PAs in present-day German occurred in OHG and partly also in Middle High German (MHG) as separate words in the same order as later within the PAs.Footnote 10 Not surprisingly, no change in word order can be observed during the process of univerbation. Therefore, it is plausible that the order of elements within PAs is due to syntactic rules rather than to word-internal principles.Footnote 11 Thus, PAs can be seen as another instance proving Givón’s dictum “today’s morphology is yesterday’s syntax” (1971:413). We will see that, in the words of Bybee (Reference Bybee2010:110), since “morphosyntactic patterns are the result of long trajectories of change, they may be synchronically arbitrary; thus the only source of explaining their properties may be diachronic.” Bybee highlights element ordering as one of these characteristics.

The position of da and hier as first element can be observed in adverbial phrases as well in present-day German. These elements express a more general spatial deixis which is followed by a deictic element that is more specific in phrases like da oben ‘up there’ or hier unten ‘down here’. To find this order in PAs comes as no surprise when the adverbial character of the elements involved is taken into account. Thar(a), dar(a) originally expressed a general spatial deixis which could be followed by an adverb expressing a more specific spatial deixis, as in the following examples:

This leads us to ask why the elements da, hier, and wo occur as first elements in PAs. As already mentioned, Müller assumes that da is suitable for the repair strategy because it is a very general, polyfunctional element, with little meaning on its own. It is reasonable to assume, however, that it is not its polyfunctionality, but its local character which is the crucial reason that da can occur in PAs. It is uncontroversial that the OHG forms thâr, dar clearly show that the first element in PAs originally expressed spatial deixis. Hier expresses local deixis as well and wo is a local adverb (going back to OHG uuâr ‘wo’, uuăra ‘wohin’; see DWB1, vol. 30, 1668, l. 24).Footnote 12 Paul (Reference Paul1919, §136, fn. 3) notes that there were combinations with the negative local adverb nirgend ‘nowhere’ (for example, nirgend ab, nirgend an, nirgend für, etc.) in OHG. Therefore, there is no doubt regarding the local origin of the first element of PAs. Moreover, the first elements in English PAs there, here, and where, as well as the R-pronouns in Dutch point in this direction.Footnote 13

The fact that the elements of PAs were originally local adverbs supports the analysis presented here that the order of elements in PAs is due to the word order in adverbial phrases with spatial meaning. This provides an explanation for the order of elements in PAs. In the next section, the process of univerbation will be investigated further.

5. Univerbation of Adverbial Phrases

As pointed out above, PAs originate from two (mostly local) adverbs forming an adverbial phrase. In this context it is important to note that PAs (in the narrow sense) only are formed from so-called primary prepositions, such as an ‘at’, auf ‘on’, aus ‘out’, bei ‘near’, durch ‘through’, für ‘for’, gegen ‘against’, hinter ‘behind’, in ‘in’, mit ‘with’, nach ‘after, to’, neben ‘beside’, ob ‘because of’, über ‘above’, um ‘around’, unter ‘under’, von ‘from’, vor ‘before’, wider ‘against’, zu ‘to’, zwischen ‘between’.Footnote 14 These elements also occurred or still occur as adverbs and therefore are sometimes called “prepositional adverbs” (“präpositionelle Adverbien,” for example, DWB1, vol. 30, 1678, Fleischer Reference Fleischer1982: 299 “Präpositionaladverbien”). They are older and more grammaticalized than “secondary prepositions,” which are derived from lexemes of other word classes or syntactic phrases. These different layers of the class of prepositions exhibit a number of distinguishing characteristics. Primary prepositions were originally local prepositions but have developed various meanings and are polysemous. They usually govern the dative and/or accusative case. Secondary prepositions mostly have only one meaning and often govern the genitive case.Footnote 15

It is assumed that primary prepositions can be traced back to adverbs which later attracted verbal complements, thereby becoming prepositions (Paul Reference Paul1920:292).Footnote 16 Their use as adverbs is not very common in present-day German, as already pointed out. Secondary prepositions can be traced back to elements of other classes and are due to conversion of nouns or participles, derivation, or univerbation.

Some authors also count wegen and während among primary prepositions (Diewald Reference Diewald1997:66, Helbig & Buscha Reference Helbig and Buscha2007:353ff.), although these elements also have some characteristics typical of secondary prepositions. They can be traced back to other word classes: wegen > dative plural of the noun Wegen ‘ways’, während ‘while’> während, participial form of währen ‘to last’. Another argument against counting them among primary prepositions is provided by PAs. Wegen and während do not behave as primary prepositions with regard to the formation of PAs (*hierwährend, *wowegen). Rather, they form adverbs with case-marked demonstrative pronouns, as in währenddessen ‘meanwhile’ and deswegen ‘therefore’. The formations consisting of a preposition and a demonstrative pronoun contain secondary prepositions and preserve the distinction between pre- and postpositions as well as the case requirements of the adposition. These lexemes contain mainly prepositions, as in währenddessen ‘meanwhile’, trotzdem ‘nevertheless’, zudem ‘additionally’, vordem ‘heretofore’, and postpositions in a minority of cases, as in deswegen ‘therefore’, demzufolge and demnach ‘according to that’. This means that the order of elements in these lexemes corresponds to the order in the syntactic phrases from which they are derived (seiner Meinung nach ‘according to his opinion’ > demnach, dem Bericht zufolge ‘according to his report’ > demzufolge, der Liebe wegen ‘because of love’ > deswegen). Therefore, univerbation is also plausible here, since it can explain their characteristics. Considering that their constituents are an adposition and a pronoun and that they fulfill pronominal functions, they might consequently be counted as PAs.Footnote 17 Like secondary prepositions, they can be conceived of as more recent members of the class. By analogy with secondary prepositions, they might be named “secondary pronominal adverbs.”

In view of these facts, the question arises as to how what was originally an adverb came to be reanalyzed as a preposition heading a PA. The ambiguity of the second elements that could be adverbs or prepositions provided the basis for extending the pattern to some elements that were originally not adverbs. The diminishing frequency of the use of the second elements as adverbs may have contributed to their reanalysis as prepositions.

6. Grammaticalization Processes

The following section will demonstrate that the univerbation of PAs is accompanied by several processes generally associated with grammaticalization. There is a semantic bleaching of the local meaning and a concomitant strengthening of textual functions of PAs as well as a rise of metaphorical meanings. These changes correspond to tendencies observed by Traugott in a number of papers (for instance, 1988, 1989) as being typical of grammaticalization. One of these tendencies is that meanings based in the external described situation change to an internal (evaluative/perceptual/cognitive) described situation. Another tendency is a shift from an external or internal described situation to textual functions (Traugott Reference Traugott1989:34f.).

Additionally, there is a phonological reduction of da and wo in PAs as well as a loss of syntactic separability of the two elements of PAs. The reduced forms can be compensated for by more expressive forms; this is a development which can be seen as part of a grammaticalization cycle. Moreover, if reduced forms can no longer be replaced by full forms in certain contexts, there is a split which is typical of grammaticalization processes.

6.1 Semantic Bleaching

Let us first look at semantic changes. Semantic bleaching is often considered typical of grammaticalization processes. Also, concrete meanings can be the basis for more abstract, metaphorical meanings (see, for example, Heine et al. Reference Heine, Claudi and Hünnemeyer1991, Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott1993, Diewald Reference Diewald1997).

As discussed above, the first elements of PAs da and hier originally were local adverbs expressing spatial deixis and wo had a local meaning as well. There is semantic bleaching because these elements lost their local character. The deictic meaning of da and hier, however, is not completely lost, since it can sometimes still occur contrastively. Consider the following example in which hier expresses greater closeness to the speaker than da:

Curme (Reference Curme1922:183) gives the example dadrin, nicht hierdrin. Apart from these contrastive examples, hier is usually seen as a stylistic variant of PAs with da, but it also can express a special emphasis and greater closeness to the speaker compared to da. Footnote 18

As Sandberg (Reference Sandberg2004) points out, a local meaning of da within PAs is only possible if there are several alternatives that were already mentioned or are salient in the situation. This means that an accent on da in a sentence like Leg die Decke DArauf ‘Put the blanket on here’ can only be a focus accent. Also a question like Worauf soll ich die Decke legen? ‘What shall I put the blanket on?’ is only possible when several alternatives have been mentioned or are obvious from the situation. A “neutral” question would be introduced by wohin ‘where to’.

One of the tendencies postulated by Traugott, the shift of meaning from describing an external situation to describing an internal situation, can be observed in a number of PAs in which a local meaning is the basis for developing metaphorical senses. For instance, dagegen denotes movement, for example, against an object (da war eine Mauer, er rannte dagegen ‘there was a wall, he ran against it’), but it also has the meaning of mental opposition (for example, er spricht/argumentiert/hat Einwände dagegen ‘he speaks/argues against it’). Another case in point is danach, which has primarily a directional meaning, but also denotes mental goals, as in sie strebt danach ‘she strives for it’, sie sehnt sich danach ‘she longs for it’. Darauf also has a directional meaning, as in sie ging darauf zu ‘she went towards it’, and also denotes ‘an inner, mental direction’ (DWB1 vol. 2, 760) with verbs like sehen ‘look after’, achten ‘pay attention to’, merken ‘realize’, hoffen ‘hope’. Also, dazu denotes movement towards a place or a goal but also a motivation or capability to do something, as in er hat keine Lust dazu ‘he is not in a mood for it’, or sie ist dazu fähig ‘she is capable of it’. These examples are instances of the metaphorical processes “nonphysical in terms of physical” as well as “abstract relations in terms of physical process or spatial relation” (Heine et al. Reference Heine, Claudi and Hünnemeyer1991:31).

Another semantic-pragmatic tendency proposed by Traugott is a shift from describing external or internal situations to textual relations. The use of PAs as cataphoric and anaphoric elements as well as relative elements (in the case of wo-PAs) constitutes such a shift. For da-PAs, the function as a correlate of subordinate clauses is also a case in point (see ex. 3).

As we have seen, da has largely lost its local deictic meaning in PAs. The fact that it can carry a focus accent can be seen as a shift from the descriptive to the textual functions that Traugott postulates as being typical of grammaticalization. We will call it the focus form of PAs as opposed to the neutral form and the reduced form. All three forms may occur as arguments or adjuncts. The reduced forms are mainly colloquial but can occasionally be found in written language (see section 7).

All three forms may occur as a correlate of complement clauses (18a), but only the focus form may occur as a correlate of adverbial clauses (18b):

This difference is due to the function of the correlates of complement and adverbial clauses. Correlates of complement clauses (subject and object clauses) bear the morphosemantic features of the argument position which is filled by the complement clause. Whereas the function of complement clauses is not determined by the complementizers introducing them and may be signaled by a correlate, the type of adverbial clause is determined by the adverbial conjunction. As a consequence, a correlate is not necessary to mark the type of an adverbial clause. For instance, a correlate darum (or deshalb, deswegen) for a causal clause introduced by weil ‘because’ is not necessary to indicate the type of adverbial clause, which is already signaled by the sentence connector. Also with polysemous connectors like wenn ‘if, when’, which can introduce temporal or conditional clauses, or dass ‘that’, which may introduce final or consecutive clauses, correlates do not disambiguate the adverbial type. Their function is purely on the level of information structure. A correlate functions as a focus exponent and integrates the adverbial clauses into the information structure of the matrix clause signaling that the adverbial clause is focused, whereas the matrix clause contains background information. For this reason, only the focus form of PAs may occur as a correlate of adverbial clauses (Pittner Reference Pittner1999: 223ff.; see also Oppenrieder Reference Oppenrieder1991b, Breindl et al. Reference Breindl, Volodina and Hermann Waßner2014: 34).

A correlate signals that the adverbial clause is focused and that the matrix clause contains background information. The correlate in (20) is unfelicitous, since the context suggests that the sentence is all-focus and the matrix clause is not backgrounded (see Pittner Reference Pittner1999:224).

An adverbial clause may also be integrated prosodically and focused without a correlate, but this is not marked in written language.

As this section has shown, PAs have largely lost their local deictic meaning, and this change serves as a starting point for developing metaphorical meanings that often relate to mental states. The spatial meaning of PAs also provides the basis for developing textual functions as anaphoric and cataphoric elements. An accent on da in PAs has textual functions: it is a focus accent occurring with PAs as arguments and adverbials as well as in their function as correlates of subordinate clauses.

6.2 Phonological Reduction

A concomitant of grammaticalization is a reduction of forms and loss of phonological substance, which can be observed with da-PAs and wo-PAs. In OHG, thâr, dar and hwâr, wâr were dative forms, dara and wara were accusative forms (Paul Reference Paul1919:154f.). In MHG, there was no longer an ending -a for accusative, but the differentiation between dative with a long vowel and accusative with a short vowel was still made.Footnote 19 The older forms of the directional adverb war and wor became rarer and disappeared in the sixteenth century (DWB1, vol. 30, 1668). The long vowel of dâr and wâr in PAs was reduced to a short one, and its form was assimilated to the vowel in the free lexemes da and wo.

Grimm (DWB1, vol. 2, 654) assumes that a deaccentuation of the first element was the trigger for univerbation. If dar was unstressed in MHG it could be reduced to der (derbî, dermite, dernider, dervon, dervor, derzuo) or the vowel or the first syllable was left out completely, as in drabe, dran, drinne, drobe, drumbe, drunder, druz. The shortened forms with dr- are common in present-day German, mainly in colloquial language (see sections 7 and 8).

Besides the reduction of the vowel of the first element, PAs with da und wo show a further loss of phonological substance (for a different development of PAs with hier see below). In these PAs, the /r/ of the first element gradually disappears, subject to a phonological condition. In present-day German, /r/ must occur before a preposition with an initial vowel and it cannot occur if the second part starts with a consonant.

The older form dar was still used in Early New High German (ENHG) and was the more frequent form. Luther uses da rather consistently in PAs when it is followed by a consonant but also dar sometimes in front of a consonant, as in darnach und darnider (DWB1 vol. 2, 654). A number of PAs had competing forms with dar and da for a long time (DWB1 passim). Today, dar can occur in PAs only when followed by a vowel, but it can still be found before consonants in some verbs like darstellen ‘to show’, darlegen ‘to explain’, darbieten ‘to present’, darniederliegen ‘to be laid low’.

These developments can essentially be seen as an optimization of syllable structure leading not only to a better syllable contact but also to a better syllable structure. A syllable contact V$V violates several constraints for an optimal syllable contact, whereas V$CV is a much better syllable contact, as stated by Vennemann (Reference Vennemann1988:40) in the “Contact Law” given in (22):

Moreover, not only the syllable contact, but also the second syllable itself is improved by /r/, according to Vennemann’s “Head Law” in (23):

When the /r/ is retained, a resyllabification takes place. The /r/ is no longer seen as part of the first element of the respective PAs, but as the first consonant of the second syllable. This is due to an optimization of syllable structure: according to the Head Law, a syllable starting with a consonant is better than one starting with a vowel. This resyllabification is reflected in speech as well as in written language, where the hyphen at linebreaks may occur before the /r/. Footnote 20

Whereas /r/ increasingly disappeared in free lexemes with da and wo and was eliminated in PAs before consonants, the development of PAs with hier was different. Hie(r) as a freely occurring stem was used increasingly more often only with the final /r/. Today, the earlier form hie occurs only in phrasemes like hie und da ‘here and there’. As a consequence, the earlier form hie in PAs is replaced by hier. The older forms without an /r/ like hiefür, hiegegen, hiemit, hienach, hievon, hieunten, hiezu are no longer in use. This makes it plausible that a kind of “stem principle” is at work, where the first element of PAs corresponds to the respective free lexeme. The preservation of the stem of the freely occurring lexeme hier ranks higher than the phonological rule which applies to the occurrence of /r/ in PAs with da and wo. Also, in the case of hier, the /r/ is part of the second syllable in spoken language if it is followed by a vowel.Footnote 21

To sum up, phonological reduction of the first part of PAs is subject to the condition that the integrity of the freely occurring stem is preserved. The first elements OHG hwâr, wâr and MHG wâ, and dâr, thâr as freely occurring lexical items are reduced to wo and da in New High German (NHG), whereas the older form hie was replaced by hier as a free lexeme. As a consequence, /r/ tends to occur more and more in PAs with hie(r) and gradually disappears in PAs with wo and da. As was shown, the deletion of /r/ is subject to a phonological condition, which can be seen as an optimization of syllable structure. If the second element begins with a vowel, /r/ must occur.

This means that there is an assimilation of the first elements to the freely occurring lexemes, and the /r/ of the first element is preserved with da and wo before a preposition with an initial vowel in order to avoid a hiatus and optimize syllable structure.

6.3 Loss of Syntactic Separability

A loss of syntactic independence and a decreasing separability is seen as a concomitant of grammaticalization (for instance, by Lehmann Reference Lehmann1995:148). Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath, Heine and Narrog2011) speaks of coalescence, which comprises a loss of interruptibility and a loss of positional variability in addition to a loss of phonetic independence.

In contrast to English, German does not exhibit preposition stranding with all kinds of prepositional complements which may be moved away from their preposition (for example, what are they talking about?/*Was sprichst du über?). Rather, this phenomenon is restricted to PAs.

In earlier stages of German, the first and second elements of what later developed into PAs were spelled with a space in between and could be separated by other elements (see DWB1, vol. 2, 654).Footnote 22 Historical grammars and dictionaries provide ample evidence that the elements of what later became PAs can occur separately in earlier stages of German.

This kind of “preposition stranding” is often called a ‘splitting construction’ (“Spaltungskonstruktion”) in the German literature. For ease of exposition and understanding, I will use the term preposition stranding.

This construction occurred as early as in OHG, as Russ (Reference Russ1982:315) states: “In OHG, examples of both straddle and non-straddle position of da(r) + preposition are to be found.” Behaghel (Reference Behaghel1932:237) points out that this can also be found in other older Germanic languages. Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2008:213) shows that this construction occurred continuously during the diachronic development of German. A few examples may suffice here:

Given the historic evidence, it is reasonable to assume that this construction, which still occurs in some dialects as well as in colloquial language, is a remnant of its more productive use in earlier stages of German. Paul (Reference Paul1919:158), for instance, notes that the separation is preserved in colloquial languageFootnote 23 and provides a number of examples starting from MHG, although the examples become rarer over the course of time. Footnote 24

In present-day German, syntactic separation is possible in colloquial language and in dialects mainly in the northern area, as Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2002) shows in his extensive study on PAs in German dialects.Footnote 25

Preposition stranding is even more restricted for prepositions with an initial vowel, which is only possible in some northern regions of Germany (see Fleischer Reference Fleischer2002). Spiekermann (Reference Spiekermann2010) sees the origin of preposition stranding (as well as doubling and deletion of the adverb) in dialects and states that it is increasingly used in regional language which is close to a (regional) standard variety.

Oppenrieder (Reference Oppenrieder, Fanselow and Felix1991a) argues that in cases like (27) there is no preposition stranding. According to him, these putative cases of prepositional stranding are due to a doubling construction and deletion of the repeated element. Since this deletion is possible if the element is identical, an obvious problem for this analysis is that prepositional stranding also occurs with wo where the deleted element is da, which is not identical, as in (28b).

A critical discussion of this and some other analyses which have been proposed is provided by Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2002). It is sufficient for the purposes of this article to note that syntactic separability of the two elements of PAs is subject to some restrictions in present-day German and is, at best, only marginally acceptable in the standard variety.

Preposition stranding provides a further parallel between PAs and formations with wo or da as first element and a directional adverb as second element. We find this kind of split also with woher or wohin, where the second part is undoubtedly an adverb (indicating a direction towards or away from the speaker):

In contrast to preposition stranding, this kind of splitting construction is also possible in the standard variety.

Otte-Ford (Reference Otte-Ford2016:264 and passim) assumes that preposition stranding with PAs is due to the “structural consequences of orality” and demonstrates its information structural function. It allows da to occur in the topic position, whereas the preposition is part of the comment. The first da can be anaphoric and represents the topic, whereas the preposition later in the sentence is part of the comment:

A preposition without an overt complement can be the result of a deletion of da due to “topic drop,” as a number of authors have suggested (for instance, Oppenrieder Reference Oppenrieder, Fanselow and Felix1991a, Otte-Ford Reference Otte-Ford2016).

Since prepositional stranding is restricted in present-day German and mainly occurs in regional language and dialects in northern Germany, a loss of syntactic separability has taken place at least in the standard variety and spoken language in central Germany and southern parts of the German language area.Footnote 27

7. Further Reduction and Split

Further phonological reduction is possible in the PAs with dar, which may be reduced to dr- (for example, dran, drüber, drunter, drum) if the second element starts with a vowel. They may occur as prepositional objects (32a), adverbials (32b), and also in their function as sentence connector (contrary to Duden 2005:585) (32c):

These forms are frequently used in colloquial German and are obligatory even in Standard German in many phraseological expressions, in particle verbs and some compounds. If the reduced forms can no longer be substituted by the full form, there is a split between the full and the reduced form which can occur during grammaticalization (see Heine & Reh Reference Heine and Reh1984:57ff., Diewald Reference Diewald1997:21). This kind of split can be observed in phrasemes as in (33a), fixed coordinations with an idiomatic meaning (33b), and particle verbs with a PA as first element (33c), as well as in other word-formations with PAs as one of their constituents (33d).

Only in a few of these phrasemes and lexemes can the reduced form still be replaced by the full form or a PP, as in dran sein > an der Reihe sein (‘to be one’s turn’), es (voll) drauf haben > es auf dem Kasten haben (‘to have the skills’), drauf kommen > darauf kommen, auf eine Lösung kommen (‘to find a solution’). In many of these combinations, dr- can no longer be replaced by dar. In these cases, the forms with dr- constitute splits of the more grammaticalized form from the full form.

8. Weakening and Strengthening: A Grammaticalization Cycle

The weakening of elements by their phonological reduction and semantic bleaching can lead to an opposite development: these reduced elements are replaced by more expressive ones, leading to a grammaticalization cycle. An example for this is hui ‘today’ in Old French which was replaced by French aujourd’hui (‘on the day of today’) or German heute ‘today’. This was reduced from hiu dagu and may be replaced by am heutigen Tage ‘on today’s day’), if heute does not have enough weight (see Keller Reference Keller1994:149f.). A similar development can be observed with the preposition vor (‘before’), which can be replaced by im Vorfeld (‘beforehand’) in certain contexts in order to give it more weight.

As already mentioned, PAs with dar may be further reduced if their first part is unstressed, as in drauf, drüber, drunter, draus etc. This is common in colloquial language and dialects in central Germany and southern parts of the German language area. These reduced forms may be strengthened again by an additional da. This kind of doubling may be close (da drauf ‘on there’ etc.) or occur at a distance (Da geb ich nichts drauf ‘I don’t give a damn about it’).

Distance doubling is sometimes seen as functionally equivalent to preposition stranding and treated together with it.Footnote 28 There is a clear areal distribution that Behaghel (Reference Behaghel1899:244) described succinctly: The southern German doubling da weiß ich nichts davon is equivalent to da weiß ich nichts von in the north of Germany.

Doubling has given rise to different explanations. Footnote 29 Spiekermann (Reference Spiekermann2010) sees a change from a synthetic to an analytic coding in the use of separated PAs and in doubling. Otte-Ford (Reference Otte-Ford2016) explains the use of the separate forms by a tendency of German to form syntactic brackets. The tendency to form syntactic brackets can explain distance doubling and distance forms, but it cannot account for close doubling.

While distance doubling may be functionally equivalent to preposition stranding in present-day spoken German, it is a rather new development; prepositional stranding is, however, very old and a remnant of earlier stages, as has been pointed out. Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2008: 218) finds the first example of distance doubling in manuscripts from the fourteenth century.Footnote 30 Close doubling is an even more recent development and can be traced back to the eighteenth century (Fleischer Reference Fleischer2008:220).

Close doubling is often not recognized by grammarians since it is considered to be nonstandard. Duden (2016:593) gives the examples dadran ‘there at’, dadrauf ‘there on’, wodran ‘where at’, wodrauf ‘where on’, hierdran ‘here at’, hierdrauf ‘up here’, and identifies them as spoken language mainly in southern and central Germany. Like prepositional stranding, these formations are “not standard but rather regional language” (Duden 2016:593) and occur more often with prepositions starting with a vowel (Negele Reference Negele2012:111).

I would like to propose that close doubling can be seen as a more advanced stage of grammaticalization within a grammaticalization cycle (see Pittner Reference Pittner2008). The best-known example is probably Jespersen’s cycle for negation, which has been observed in a number of languages in which “the original negative adverb is first weakened, then found insufficient and therefore strengthened, generally through some additional word, and this in turn may be felt as the negative proper and may then in the course of time be subject to the same development as the original word” (Jespersen Reference Jespersen1917:4). A very similar development can be observed with PAs, where the first element is at first weakened and then reinforced by an additional element.Footnote 31

Close doubling occurs most often with the reduced forms. Ample material for the construction provided by Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2002) shows that in the dialects the second da is either a reduced form (dr-) or another form which is deaccented and contains less phonological material than the first da, which is added to strengthen the weakened element (see also Fleischer Reference Fleischer2002:284 and the literature quoted there).

A separate accented da is the means to express local deixis. If local deixis is intended, only the spelling of da as a separate adverb is possible. The corresponding PAs have lost their local deictic meaning. Semantic bleaching and phonological reduction lead to a weakening of local deixis, which is again strengthened by an additional da:

The following examples illustrate that a separate accentuated da can express local deixis, while there is no local deixis in the corresponding PAs. It seems that the deictic potential of da in these PAs is so far reduced that an additional deictic element seems appropriate.

Da rum, da rein, da runter, however, are not reduced from PAs, but reduced from the adverbs da and her/hin + preposition. In Standard German, the shortened forms make no distinction between her, which expresses movement towards the speaker, and hin denoting movement away from the speaker.Footnote 33 Therefore, forms like rein and runter when denoting movement away from the speaker cannot be traced back to the full forms, which would be hinein or hinunter. In these cases, there is a split between the full and the reduced forms. The reduced forms with a separate deictic da are clearly distinguished from the corresponding PAs by the double accent and a pause in spoken language and a space in written language.

9. Conclusions

The internal structure of PAs has often been explained by the movement and substitution of an NP-pronoun by an R-pronoun. After reviewing some of these analyses and pointing out some problems, an alternative account based on the diachronic development of PAs was presented. It was argued that the pattern of PAs can be traced back to the univerbation of two separate adverbs which formed an adverbial phrase expressing spatial deixis. The second element could be an adverb or a preposition. This ambiguity was the basis for a reanalysis of the second element as a preposition.

It was shown that the univerbation is accompanied by processes that are typical concomitants of grammaticalization, among which are bleaching of meaning, the development of metaphorical meanings as a shift of descriptive to textual functions, as well as phonological erosion.

From a diachronic perspective, separately occurring elements of PAs often considered to be a form of preposition stranding are a remnant of earlier stages where the two elements occurred as separate words. This is preserved today mainly in the dialects and colloquial language in northern Germany.

If da- is reduced to dr- and can no longer be replaced by the full form, there is a split between the more grammaticalized forms and their source. Doubling of the first element of PAs was argued to be the result of a weakening of this element that has taken place. Weakening of forms can lead to a reinforcement by additional elements, which constitutes a grammaticalization cycle.

From a diachronic point of view, the question concerning the development of PAs is not how they can be derived from the partially functionally equivalent syntactic phrases consisting of a preposition and a pronoun, but rather how the second element, which was originally an adverb, came to be reanalyzed as a preposition. The ambiguity of the second elements which occurred both as adverbs and as prepositions allowed the second element to be reanalyzed as a preposition. That PAs function as adverbs which are replacing full PPs promoted the classification of the second element as a preposition. The decreasing use of the second elements as adverbs may have contributed to this development.

Acknowledgments

This article builds on earlier work done in Pittner (Reference Pittner2008). I am indebted to two anonymous reviewers, the editor, and Daniela Elsner for their helpful comments and suggestions.