1. Introduction

This paper examines the possible origins of wh-ever constructions in contemporary American Hasidic Yiddish. Documented in neither Yiddish grammars nor in contemporary Israeli Hasidic Yiddish, these constructions are used in American Hasidic Yiddish in concessive conditionals (specifically, universal concessive conditionals; Haspelmath & König Reference Haspelmath, König and van der Auwera1998:604–619) and nonspecific free relatives (Bresnan & Grimshaw Reference Bresnan and Grimshaw1978); they also serve as indefinite pronouns.Footnote 1

At the same time, the use of some documented equivalent Yiddish patterns decreases. For example, a common documented Yiddish pattern where the concessive conditional is marked by negation on the verb is quite rare in American Hasidic Yiddish.Footnote 2 This documented pattern with negation probably reflects contact with Slavic languages (Haspelmath & König Reference Haspelmath, König and van der Auwera1998:615–616). Consider the following example:

-

(1)

Analysis of spoken and written corpora of American Hasidic Yiddish shows that one of the ways to express the concessive conditional in 1 in this contemporary Yiddish variety is by using a wh-ever pattern (wh-imer):

-

(2)

A comparative study of contemporary American and Israeli Hasidic Yiddish recordings reveals that wh-imer constructions occur only in American Hasidic Yiddish. It seems plausible, therefore, to consider this a contact-induced change, where American Yiddish patterns converge with the English pattern of wh-ever. However, while contemporary patterns seem to reflect the impact of English, it is possible that English was not the only contact language affecting the early stages of this change. I suggest that several sources might have introduced this pattern to American Hasidic Yiddish, so that this may be a case of multiple causation (see Joseph Reference Joseph2013). Specifically, I ask whether the presence of Germanized Yiddish varieties, elevated German-like Yiddish styles, as well as contact with Judeo-German varieties during the formation of Hasidic Yiddish in Williamsburg (Brooklyn, NY) in the 1940s and 1950s might have introduced the German wh-immer into the emerging American Hasidic Yiddish varieties, where it was gradually entrenched due to its identification with the corresponding English construction.Footnote 3 Accordingly, I use the specific case of wh-imer to discuss the more general possibility of historical impact of German on American Hasidic Yiddish.

The paper is organized as follows. It starts with a short introduction to American Hasidic Yiddish and a description of the analyzed corpora (section 2), and then presents examples of wh-imer constructions and constructions with similar functions in the American corpora (section 3). Section 4, the core of the paper, discusses the possible impact of Germanized Yiddish varieties and Judeo-German on wh-imer construc-tions in American Hasidic Yiddish. Section 5 adds a comparative perspective by suggesting some possible reasons for the different extent of German influence in American and Israeli Hasidic Yiddish. Section 6 concludes the discussion by suggesting directions for future research.

2. American Hasidic Yiddish: Background and Corpora

Yiddish is currently maintained as a spoken community language only in some Hasidic groups, mostly in the US, Israel, the UK, and Belgium (Assouline Reference Assouline2018:472–473). In these close-knit communities, invariably united around a dynastic spiritual leader and preserving as far as possible the way of life of an idealized Eastern European past, Yiddish is a highly prestigious language, functioning as a powerful symbol of a distinct ethnic and religious identity (Isaacs Reference Bartal, Polonsky, Bartal and Polonsky1999). As a result, many Hasidim (plural of Hasid) continue to speak Yiddish and pass it on to their children, while also using the majority language (usually English, Hebrew or Flemish).

The exact number of Hasidic Yiddish speakers is hard to gauge. The estimated number of Hasidim worldwide in 2016 was somewhere between 700,000 and 750,000 (Wodziński Reference Assouline2018a:191).Footnote 4 However, not all Hasidim speak Yiddish. Some Hasidic groups have shifted to the majority language (for example, the biggest Hasidic group in Israel, Ger, has largely shifted to Israeli Hebrew), while in other groups Yiddish is maintained as a heritage language with limited use (for example, as a language used by men when studying sacred Jewish texts). The largest Yiddish-speaking Hasidic population is in the United States, where Yiddish is spoken in Hasidic sects such as Satmar, Bobov, Skver, Vizhnits, Belz, Munkatsh, and Pupa, located mainly in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Borough Park, in Kiryas Joel (Orange County, NY), and in Monsey and New Square (Rockland County, NY).Footnote 5 The most significant Yiddish-speaking group today is Satmar, the largest Hasidic sect (20% of the world’s Hasidim as of 2016; Wodziński Reference Assouline2018a:199), where Yiddish is maintained as a primary spoken language.

The American Hasidic sects were founded or rebuilt in the United States after World War II. Most Hasidic sects in the United States are “Hungarian” or “Galician” (Wodziński Reference Assouline2018a:209), representing dynasties of so-called “Habsburg Hasidim” (Biale et al. Reference Assouline2018:359–400). These reestablished postwar sects attracted not only their own original followers, but also other Jews, born in Europe or the United States, some of them with no Hasidic background (Fader Reference Fader2009:8–9, 223). Some possible linguistic consequences of the American Hasidic revival are discussed in section 4.

The following corpora were consulted in order to examine both spoken and written language.

(i) Spoken American Hasidic Yiddish: recorded between 2000–2011 from both men and women. Men: 12 radio interviews (from the Yiddish Kol Mevaser news hotline; Assouline & Dori-Hacohen Reference Assouline2017), featuring 12 male interviewees and 3 male interviewers (81,879 words). Women: recorded lectures and lessons by 12 women (77,546 words).Footnote 6

(ii) Written American Hasidic Yiddish: A corpus composed of two American Hasidic Internet forums, a total of approximately 85 million words: ivelt active since 2007 and kaveshtiebel active since 2012. These forums are designated male-only, yet participants contribute anonymously, and it is possible that some women participate under the guise of men. The Yiddish in both forums is heavily influenced by English and it seems that most participants are American.

(iii) Written Yiddish: the online database Yiddish Book Center’s Full-Text Search (10,055 Yiddish books as of December 2020; mostly prewar East-European Yiddish); and the online database of Otzar HaHochma (110,564 Judaic books as of December 2020, including about 6,000 Yiddish books and about 500 Judeo-German books). There is almost no overlap between the Yiddish texts in these two databases.

(iv) Spoken Israeli Hasidic Yiddish (recorded between 1995–2007): male and female speakers, 250 recorded hours of lessons, lectures, and sermons (Assouline Reference Assouline2017:27).

In the next section, I discuss the distribution of wh-imer constructions in the American corpora (i and ii above). I demonstrate that they occur in concessive conditionals, nonspecific free relatives, and as indefinite pronouns, and provide examples of each use.

3. Wh-Imer Constructions in the American Corpora

Wh-imer constructions were documented in the American corpora in concessive conditionals and in nonspecific free relatives. They also function as indefinite pronouns. Wh-imer patterns in the American corpora (in concessive conditionals, nonspecific free relatives, and as indefinites) were documented mainly among male speakers, and probably male writers too (since the analyzed Hasidic forums are supposedly confined to men). Wh-imer constructions may thus be identified with more elevated and formal Yiddish styles of public speech and writing. It is also possible that these constructions are more commonly used by men, yet the limited number of female speakers in the analyzed corpora prevents one from drawing such a conclusion. Only a single occurrence of wh-imer in the speech of a female speaker was documented in the spoken corpus.Footnote 7 The precise status and use patterns of wh-imer in the speech community can only be established by means of a more exhaustive study among American Hasidic speakers. At present it is not clear whether wh-imer patterns are also common in everyday spoken Hasidic Yiddish.

Furthermore, the word imer itself is not used in spoken Hasidic Yiddish in the sense of the German immer ‘always’ (rather, štendik and ale mol ‘always’ are used in Israeli Yiddish, and aybik/aybig ‘always’ in American Yiddish), so its uses in spoken American Hasidic Yiddish are restricted to the wh-imer constructions.Footnote 8 Note, however, that imer ‘always’ is commonly used in American Hasidic Yiddish texts, as are many other Germanisms (see section 4 below).

3.1. Concessive Conditionals

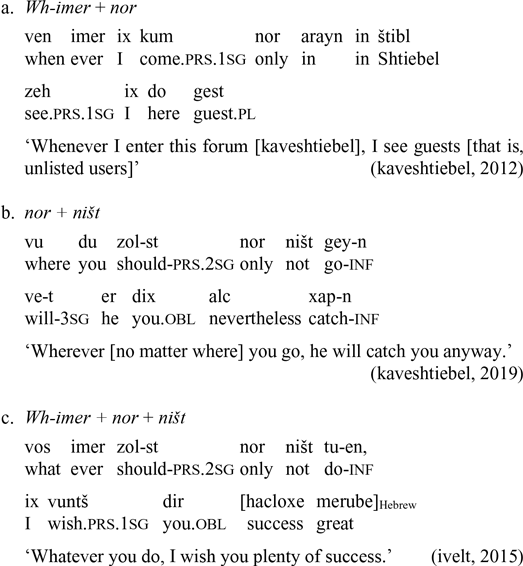

Three different patterns of concessive conditionals are attested in the written American corpus: a pattern with nor ‘only’, a wh-imer pattern, and a pattern marked by negation. These three constructions can also be combined (see the examples in 6 below). In the spoken American corpus, only the first two patterns (the only-pattern and the wh-imer) are attested.

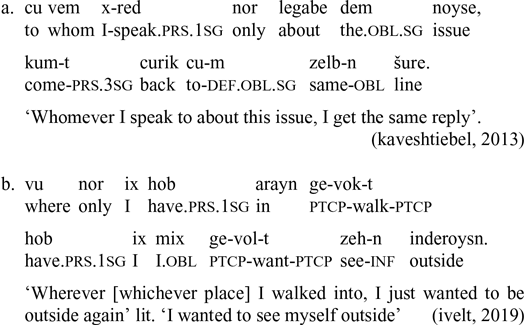

Consider the following examples of the three patterns. First, there is a construction with the restrictive focus particle nor ‘only’ (documented in East-European Yiddish; Haspelmath & König Reference Haspelmath, König and van der Auwera1998:613), with nor usually following the wh-word or the verb. This is the most common pattern in the written corpus, appearing in about 60% of all concessive conditionals:Footnote 9

-

(3)

Second, there is a construction with wh-imer (vos imer ‘whatever’, ver imer ‘whoever’, vem imer ‘who(m)ever’, ven imer ‘whenever’, vu imer ‘wherever’, vi/vi[a]zoy imer ‘however’). This construction is used in about 30% of all concessive conditionals in the written corpus:

-

(4)

The third pattern is marked by negation (subjunctive + negation + infinitive), as shown in 5. This pattern is relatively less common in the written corpus and was not attested in the spoken corpus.

-

(5)

The three patterns can also be used together, as in 6.

-

(6)

The estimated proportion of the different patterns in the written American corpus (the ivelt and the kaveshtiebel databases together comprising circa 85 million words; see ii in section 2 above) is presented in table 1.Footnote 10

Table 1. Frequency of concessive conditional patterns in the written American corpus (CI 95%).Footnote 11

As can be seen from table 1, the pattern with nor is the most common in the American Hasidic written corpus, and the pattern wh-imer the second most common.Footnote 12 The pattern with negation is the least common, with its proportion in the written corpus (including combinations with other patterns) about 7% of all concessive conditionals.

3.2. Nonspecific Free Relatives and Indefinite Pronouns

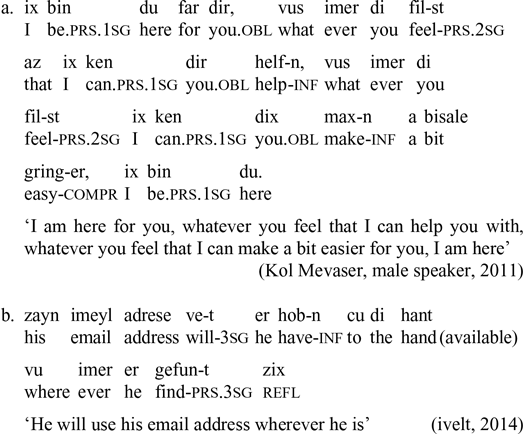

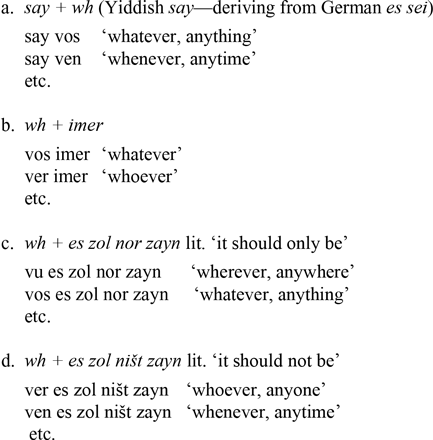

In both spoken and written American corpora, wh-imer constructions are commonly used in nonspecific free relatives, or “fused relatives” (Huddleston et al. Reference Huddleston, Pullum, Peterson, Huddleston and Geoffrey2002:1068), such as zey tuen vos imer zey viln ‘they do whatever they want’. Besides, wh-imer constructions also serve indepen-dently (as in vos imer ‘whatever’), alongside several other series of free-choice indefinite pronouns and parallel nonspecific free relatives (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath1997:52, 55). Consider the following examples of indefinites and lexicalized nonspecific free relatives expressing free choice in the American corpora, all with a meaning similar to ‘anyone, whoever’, ‘anything, whatever’, ‘anywhere, wherever’, etc.

-

(7)

The free-choice indefinite pronouns in 7a are the most common type in the written corpus followed by the ones in 7b. The two lexicalized nonspecific free relatives in 7c,d are rarely used, probably due to their length and complexity, which restrict their use to specific syntactic environments. Thus, for example, while say ver ‘whoever’ was documented 775 times in the written corpus and ver imer (as the indefinite ‘whoever’) 105 times, the longer patterns were less frequent, with 9 occurrences of ver es zol nor zayn ‘whoever’ and 3 occurrences of ver es zol ništ zayn ‘whoever’. Note that these constructions can also be combined, thus emphasizing the sense of free choice that they imply (for example, say ven imer ‘whenever’, vu imer es zol nor ništ zayn ‘wherever’, say vos es zol nor zayn ‘whatever’). Besides, free-choice indefinites are expressed in both American corpora in additional ways, as, for example, with the borrowed eni ‘any’ + N: eni zax ‘any thing’.

The distribution patterns of the different free-choice indefinite pronouns in the American corpora are complex and are not discussed here. For the present purpose, it is sufficient to note that wh-imer free relatives and indefinites are commonly used in the American corpora.

4. The Origins of Wh-Imer in American Hasidic Yiddish

Having established that wh-imer is commonly used in the corpora of men’s written Yiddish and public speech, the next step is to consider the origins of wh-imer in American Hasidic Yiddish. It is possible that contact with English is affecting this Yiddish construction, and it appears that Yiddish speakers identify wh-imer with the parallel English wh-ever.Footnote 13 While English seems to affect contemporary patterns of use, however, it is possible that English was not the only source of this construction in American Hasidic Yiddish. I suggest that these constructions were not necessarily introduced to American Hasidic Yiddish as calques of the English wh-ever, and that they may have been accessible to speakers directly through Germanized Yiddish dialects, German-like formal Yiddish styles and contact with Judeo-German varieties (see section 4.1 below). In other words, I suggest that these Yiddish constructions may not have been innovations based on English patterns, but rather patterns already familiar to some Yiddish speakers due to the direct and indirect impact of German varieties. Their dissemination in American Yiddish, thanks to the impact of English, can be described as a gradual shift from a minor use pattern (for example, from a construction found only in certain German-like elevated Yiddish written texts) to a major use pattern, found in various contexts of use (Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005:44–62).

In order to examine this hypothesis, I first turn to the dialectal makeup of American Hasidic Yiddish and the possible impact of German and Germanized Yiddish varieties during its formation. Note that written American Hasidic Yiddish (mainly Satmar Yiddish) manifests German-like orthography and abounds in German loanwords (Krogh Reference Aptroot2014). This is also evident in the written corpus, which manifests a tendency toward Germanized orthography and contains hundreds of Germanisms such as alzo ‘so’, manxe ‘some’, umfarmaydbar ‘inevitable’, etc. Both the Germanized orthography and the use of German loanwords follow certain conventions and preferences of the so-called daytshmerish style of early 20th-century East-European Yiddish (Krogh Reference Assouline2018).Footnote 14 The present discussion suggests that German-like prestigious Yiddish written styles played a role in the rise of the wh-imer constructions and speculates that contact with spoken German and spoken Germanized Yiddish varieties might have also played a part in this process.

4.1. Multilingualism and Formation of American Hasidic Communities

Contemporary American Hasidic communities were founded in the United States after World War II. Several small Hasidic communities did exist before the war, but most Hasidic immigrants were Americanized and did not succeed in passing the Hasidic way of life to their children (Glazer Reference Glazer1957:143, Poll Reference Poll1962:19–20, 26–27). Substantial, close-knit Hasidic communities were established only after the war with the arrival of prominent Hasidic leaders and their surviving Hasidim, who settled in New York (Poll Reference Poll1962:29, Perlman Reference Perlman1991:132, Belcove-Shalin Reference Belcove-Shalin and Janet1995:8–9). Two studies conducted in Williamsburg in the 1950s shed light on the early stages of the Hasidic revival in the United States. Kranzler (Reference Kranzler1961) and Poll (Reference Poll1962) describe the formation of Hasidic groups in Williamsburg, mainly the dominant Satmar Hasidic sect led by rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum (1887–1979). After Teitelbaum settled in Williamsburg in 1946, Hasidim started to join him (a few dozen in 1948, and 860 households by 1961, according to Rubin Reference Haspelmath1997:47). Williamsburg had attracted Jewish immigrants before—mainly Galician and Polish Hasidim in the 1920s and 1930s, and refugees from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia in the late 1930s (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:18–19). Kranzler describes the arrival of surviving Hasidim after the war, who chose Williamsburg because it allowed them to continue a Hasidic way of life, offering Hasidic educational institutions, etc. (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:14, 19). The main groups forming in Williamsburg were “Hungarian”, and they also attracted new members, including Hasidim who had come to the United States before World War II (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:19, Rubin Reference Haspelmath1997:47). Williamsburg gradually became a center of Hungarian Hasidic Jews (with about 10,000–12,000 Hasidim in 1959; Poll Reference Poll1962:30), who later settled in other neighborhoods as well (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:15).

Yiddish, Hungarian, and to a lesser extent German seem to have been the common native languages of Jews in Williamsburg in the 1940s and 1950s. The term Hungarian Hasidim refers to Hasidim from “Greater Hungary”, which includes those areas that belonged to Hungary in the 19th-century Habsburg Empire (Biale et al. Reference Assouline2018:624).Footnote 15 Hasidim who came from the so-called Unterland (a Jewish folk-geographic term, referring roughly to northern Transylvania and the mountainous portions of East Slovakia and Carpathorussia; Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Lucy1964:246, 249–250, Biale et al. Reference Assouline2018:390) spoke mainly Yiddish. Orthodox (usually not Hasidic) Jews who came from the Oyberland (a Jewish folk-geographic term referring to West Slovakia, West Hungary, and the “Seven communities” of the Burgenland; Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Lucy1964:246, 249) spoke mainly German (or Judeo-German) and Hungarian (Poll Reference Poll1962:16–17, 1965:130, Perlman Reference Perlman1991:63–65, Katz Reference Belcove-Shalin and Janet1995:12).Footnote 16 Some of these Oyberlender spoke Oyberland Yiddish, one of the last Western Yiddish varieties that survived into the 20th century (Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Lucy1964:251–252, Fleischer Reference Assouline2018:245–246).

There are no exact data about patterns of multilingualism in 1940s and 1950s Williamsburg or the relative proportion of Yiddish speakers in the Hasidic communities; only some impressionistic and anecdotal descriptions regarding language use, such as observations that many Hasidic women spoke only or mainly Hungarian (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:219, Poll Reference Poll1965:135).Footnote 17

When considering the possible impact of German during the formation of Hasidic Yiddish in Williamsburg, note that German could have influenced the language of Yiddish speakers in several ways. The impact of German is evident first and foremost in the Germanized Habsburg Yiddish varieties, including Unterland Yiddish. Yet another channel through which German constructions such as wh-immer could have been introduced to the nascent Hasidic Yiddish in Williamsburg was the Judeo-German speaking Jews.

Note that the term Judeo-German refers to “a variety spoken by Jews containing special vocabulary, but not otherwise differing form (local) German” (Fleischer Reference Assouline2018:239).Footnote 18 Judeo-German speakers in Williamsburg were mostly Oyberlender, such as the “Viennese Community” (Adas Yereim Vien, Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:152, 209), and other groups of Orthodox, non-Hasidic so called Ashkenazish or Yekish Jews (lit. German Jews). Both terms, meaning ‘German’, refer in the Hungarian Jewish context to orthodox non-Hasidic streams such as Pupa, Nitra, and Kashoy. Today, such streams have become Hasidic or merged into dominant Hasidic groups (Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Lucy1964:255, Sadock & Masor Reference Assouline2018:98). The possibility of direct influence of Judeo-German is supported by metalinguistic comments such as “say ven (ven imer, oyf di yekiše šprax)…” [whenever [say ven] (whenever [ven imer] in the German language)…] (kaveshtiebel, Reference Assouline2018). Most speakers of Judeo-German (as well as German) were among the Jewish refugees from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia that came to Williamsburg in 1938 and 1939 (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:95, 257–259).

4.2. Wh-Imer in Prewar Judeo-German and Yiddish Texts

German constructions such as wh-immer might also have been present in Unterland Yiddish, but perhaps only in formal or written registers, as discussed below. Satmar Yiddish derives mainly from Unterland Yiddish (Krogh Reference Krogh, Aptroot, Gal-Ed, Gruschka and Neuberg2012), maintaining Unterland phonological, syntactic, and lexical features (for example, the use of aybik/aybig ‘always’ mentioned at the beginning of section 3 is typical of the Unterland (see ajbəg in Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Lucy1964:261).

In order to check the distribution of wh-immer/imer constructions in prewar Judeo-German and Yiddish texts, I searched the two databases of the Yiddish Book Center’s Full-Text Search and Otzar HaHochma (see iii in section 2 above).Footnote 19 Very few occurrences of wh-imer were attested in prewar Yiddish texts, as follows: Eight occurrences of wh-immer constructions were attested in Judeo-German texts written or printed between 1881–1905 in Habsburg territories, printed in Sighet, Paks, Budapest etc.; written by writers from Kleinwardein (Kisvárda), Pressburg (Bratislava), etc., for example: “…und vas immer ihm cukommt nixt vankend cu verden” [and whatever may happen to him, he should not lose faith] (Krausz Reference Krausz1899:91; Krausz was the rabbi of Jánoshalma and later of Lackenbach). Furthermore, seven occurrences of wh-imer constructions were attested in Yiddish books published in the US and Canada between 1919–1939, six of which by writers born in Habsburg territories (for example, Sarah Berndstein Smith, b. 1888 in Bustyaháza, and Samuel Rocker, b. 1864 in Görlitz). Finally, three occurrences of wh-immer constructions were attested in Unterland Yiddish texts, two of which in a text printed in Sighet in 1935, for example, “vos immer es geht fariber iber dem menš, zoll er zix ništ zorgen, den a foter tit kayn šlextc far zayne kinder” [Whatever happens to a person, they should not be worried, since a father never harms his children] (Strohli Reference Strohli1935:156); the other in a letter written in Homok (a village near Satmar) in 1936 (Gross Reference Gross2004:156).

While these databases are by no means exhaustive, the fact that very few occurrences of wh-imer were attested in thousands of prewar Yiddish texts suggests that this is not an original Yiddish construction (that is, it is not inherited from German as the source language from which Yiddish originally developed). Rather, it seems plausible that this construction was introduced to Habsburg Yiddish speakers through contact with German, and, possibly, to Yiddish speakers in the United States through contact with English.

Another interesting documentation of wh-imer is found in a postwar (transcribed) sermon delivered by the founder of Satmar, rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum: “vu imer m’kumt, broyx men mesaken cu zayn” [wherever one goes, one has to make things right] (Teitelbaum Reference Teitelbaum2006:235). This documentation suggests that wh-imer constructions might not have been limited to written texts but were used in formal spoken Yiddish as well.

The use of German and Germanized forms in written and formal-spoken Unterland Yiddish may reflect the historical impact of Western Yiddish or an impact of Oyberland Judeo-German on spoken Unterland Yiddish (Weinreich Reference Weinreich and Mark1958:193, Weinreich 1964:262–263), or rather, a stylistic tendency to Germanize Yiddish in formal contexts. Note that the tendency to Germanize Yiddish in order to elevate the language is typical of Habsburg Yiddish in general. Galician Yiddish, for example, was impacted by continued exposure to the German language under Austrian rule (Bartal & Polonsky Reference Bartal, Polonsky, Bartal and Polonsky1999:3, Silber Reference Assouline2017:790–791; see an example in Kiefer Reference Belcove-Shalin and Janet1995:272–273). Hasidic speakers of Galician Yiddish in the postwar-United States joined either Galician Hasidic groups, such as Bobov and Belz, or Hungarian groups, such as Satmar (Kranzler Reference Kranzler1961:18–20, Krogh Reference Aptroot2014:65, Sadock & Masor Reference Assouline2018). Either way, it is possible that some German features were introduced to the emerging American Hasidic Yiddish through Galician Hasidim.Footnote 20

To sum up, it is possible that Germanized Yiddish elevated styles and Judeo-German varieties influenced American Hasidic Yiddish in the early stages of its formation. German might have influenced American Hasidic Yiddish indirectly, due to its role as a prestigious linguistic model for certain Yiddish formal styles, and also directly, due to the possible impact of contact with spoken Judeo-German and spoken Germanized Yiddish varieties.

The impact of German could have made the wh-immer pattern available to Yiddish speakers, who adopted it due to its identification with the parallel English construction. Such hypothesized impact of German on spoken American Hasidic Yiddish need not be limited to wh-imer. For example, it is possible that common American forms such as vem ‘whom’ (Standard Yiddish and Israeli Yiddish vemen) also reflect German influence, but this needs further investigation.Footnote 21 Besides, dozens of Germanisms, such as urzax ‘reason’ (Standard Yiddish sibe) and nucbar ‘useful’ (Standard Yiddish nuclex/niclex), were attested in the spoken American corpus. However, these may be typical of an elevated German-like style and influenced by the Germanized written Hasidic Yiddish style rather than reflecting an organic “Habsburg” German component. Moreover, note again that in the corpus such Germanisms appeared in the formal genres of radio interviews and public sermons, and it is not clear whether they are used in everyday American Yiddish. Any attempt to examine different types of German impact on Hasidic Yiddish should therefore be highly sensitive to the different registers of use, distinguishing between formal written Yiddish (books and newspapers), less formal written Yiddish (such as Yiddish in Hasidic Internet forums), formal spoken Yiddish (such as sermons), and everyday spoken Hasidic Yiddish. Only Germanisms used in everyday speech are likely to reflect contact with spoken German: either historical contact with German in Habsburg Yiddish varieties and/or contact with Judeo-German varieties during the formation of Williamsburg Yiddish.

5. American Versus Israeli Hungarian Yiddish

It seems likely that, as well as English, both Germanized Yiddish varieties and Judeo-German played a part in the rise of the wh-imer constructions, though the relative role played by each language is hard to establish. Yet even if in this specific case the impact of German may be limited or even uncertain, it is important to note that American Hasidic Yiddish has maintained many “Habsburg” or Hungarian-Galician features, such as the use of Germanisms. This feature of American Yiddish, mainly Satmar Yiddish, becomes more salient when compared to another contemporary Hungarian Hasidic Yiddish variety, spoken in Israel. While I hope that future comparative studies of contemporary Hasidic Yiddish dialects will shed more light on the subject, some preliminary explanations for this difference may be briefly presented.

To begin with, note that the communities that best maintain Yiddish in Israel are also Hungarian, mainly “zealous” extremist groups such as Toldot Aharon (originally founded in interwar Satmar; Biale et al. Reference Assouline2018:720–721).Footnote 22 However, the spoken language of such “Hungarians” is less Germanized than American Satmar Yiddish (for example, almost no German loanwords are attested in the Israeli Hungarian spoken corpus). Two possible explanations may be suggested for this difference. First, each community had its own formation history and, as a consequence, a distinct dialectal makeup and dialect contact setting. Second, the two communities show different literacy rates in Yiddish, which may also contribute to the presence of German features in the spoken language.

Speakers of Habsburg Yiddish (mainly Hungarian Hasidim), who came to the United States after World War II, during the late 1940s and 1950s, were a rather homogenous group that was free to choose where to settle. Many of them chose to settle in Williamsburg, where they formed their own organized communities, with Hungarian and Galician Yiddish as dominant varieties. They maintained strict communal boundaries, with very limited contact with outsiders, even if these outsiders were religious Jews (Poll 1962:38). Such isolated life of a homogeneous group in one place supported the maintenance of Habsburg and typical Hungarian features, which remain evident in American Hasidic Yiddish to this day.

While the Williamsburg community appears to be an isolated Hungarian enclave formed within a single decade in a single neighborhood in Brooklyn, the formation process of Hungarian Hasidic communities in Israel was more complex. Some groups of Hungarian orthodox (Ashkenazim) and Hasidim came to Ottoman Palestine before World War I and settled mostly in Jerusalem (for example in the neighborhood batey ungarin/ungeriše hayzer ‘Hungarian houses’, established in 1891). These “Hungarians” and other Habsburg Hasidim found in Jerusalem existing Hasidic communities, where Northeastern and Southeastern Yiddish varieties were widespread (that is, Yiddish dialects that are more “Slavic”, with Slavic loanwords and syntactic calques). This is because the founders of the Hasidic communities in Ottoman Palestine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries came mainly from Eastern Belarus (Wodziński 2018a:23). As for Northeastern Yiddish, it was also used in the so-called “Jerusalemite” ascetic, non-Hasidic groups, who maintain their “Lithuanian” Yiddish dialect to this day (Assouline 2010). As a result, even the contemporary Yiddish of a largely Hungarian group such as Toldot Aharon is mixed with Northeastern Jerusalemite Yiddish, which blurs its distinct Hungarian traits. Another factor that hindered the maintenance of Hungarian features in Israel was the fact that unlike Williamsburg Hasidim in the late 1940s and 1950s, Hungarian Hasidim who came to Israel after 1948 could not always choose where to settle. These Hasidim either joined family members in different locations in Israel or were sent to temporary immigrant camps, thus postponing the creation of homogenous Hasidic centers like the one in Williamsburg.

Thus, in the United States both the relative homogeneity of the Hasidic community as well as the concentration of Habsburg, mainly Hungarian Hasidim in one location in the 1940s and 1950s supported the maintenance of Habsburg and especially Hungarian features. By contrast, dialect contact in Jerusalem and the geographical dispersion of Hasidim in Israel of the 1950s hindered the maintenance of such features.Footnote 23

The second explanation is based on the difference in Yiddish literacy rates observed within the two communities. Yiddish literacy rates are generally much higher in the United States, whereas Yiddish-speaking Hasidim in Israel read and write mostly in Hebrew (Assouline Reference Assouline2018:475). American Hasidim are thus more exposed to German loanwords common in written Hasidic Yiddish texts. As a result, higher Yiddish literacy rates may also support the maintenance of German features in the United States.

In conclusion, while contemporary Hasidic Yiddish varieties spoken in different countries are distinct mainly due to the different contact languages, their different dialectal makeup, formation history, and other sociolinguistic factors should also be considered in any comparative study of Hasidic Yiddish dialects. This is of course relevant not only to American and Israeli Yiddish, but also to European varieties. The impact of the majority language remains crucial and can explain many linguistic changes, but other factors may be important as well. For example, returning to the concessive conditional patterns discussed above, the fact that the Slavic pattern with negation is used by Israeli Hungarian speakers (while never attested in the American spoken corpus) may testify both to past and contemporary contact with speakers of the Slavic, North- and Southeastern Yiddish dialects, as well as to the impact of Israeli Hebrew, where a similar pattern exists.Footnote 24

By contrast, in the United States the Slavic negation pattern is not supported by any parallel pattern: Contact with Northeastern Yiddish speakers is very limited, and a similar pattern with negation does not exist in English.Footnote 25 As a result, the use of the negation pattern in the American corpora seems to be decreasing. Similarly, the use of wh-imer by American speakers can be attributed both to the impact of English and to the possible impact of German, due to the role played by Germanized Yiddish and Judeo-German in the development of Williamsburg Yiddish. Both factors contribute to American Hasidic Yiddish, which was in any case more “Germanic” and less “Slavic” to begin with, gradually becoming even more “Germanic”.

6. Future Research Directions

The study of Hasidic Yiddish is still in its early stages, and still suffers from the lack of scholarly interest in Hasidic Yiddish throughout the second half of the 20th century (Nove Reference Assouline2018). As a result, there is very little information about the formative years of contemporary Hasidic Yiddish dialects and the various factors affecting their development. This paper employed the construction wh-imer in order to speculate about the possible impact of German on the emerging American Hasidic Yiddish in Williamsburg. Further research is needed in order to assess the possible impact of past contact languages on contemporary Yiddish varieties. In the American case, due to the multilingual nature of the emerging Hasidic community in the 1950s, it would be fruitful to examine the possible impact of a Hungarian substrate, as well as that of a German superstrate (and possibly also substrate). Further studies in other Hasidic communities worldwide would inform our understanding of the interplay of past and present contact languages in the development of contemporary Yiddish varieties.

APPENDIX

In order to briefly illustrate the differences between Judeo-German and Germanized Yiddish texts, consider the following examples. All texts are written in the Hebrew alphabet. The transcription follows the YIVO transliteration rules, with three modifications: [c] is used instead of [ts], [š] instead of [sh], and [x] instead of [kh]. Hebrew elements are transcribed as in Standard Yiddish.

Judeo-German (from the Oyberland )

An excerpt from the will of Abraham Ratzerdorfer, written before his death in Pressburg (Bratislava), 1881:

nun yect komt di cayt … verdet mix fihren … veys velxen veg ix for mir habe, velxe grosse ferantvortung, darum mayne libe kinder am”š [Hebrew acronym; “see what I have written above”], maxt es ayx cur oyfgabe, das man zagen zoll oyf ayx, di kinder haben ayne gute ehrciung gehabt, und im yidišem veg ercogen. (Geshtetner Reference Geshtetner1990:310)

So now comes the time… [you] will guide me … [I] know which path I have in front of me, what great responsibility, therefore my beloved children, see what I have written above, make it your task that people will say about you: “The children had a good upbringing, and were raised in the Jewish way”.

An excerpt from Shtern 1905 (b. 1861 in Mád; a rabbi in Marosludas/Luduş):

indem ix diezes seyfer [book] b”h [by the help of God] der öffentlixkayt ibergebe, eraxte ix als mayne pflixt cu bemerken: ix vollte nämlix—um der kritik oys cu veyxen—am šlusse dem seyfer ayne špraxfehler berixtigung drukken lassen. aber ayn zehr geaxteter rabbiner n”y [may his light shine] in bayern, šrieb mir, das er ayne zolxe berixtigung fir höxst ungeaygnet halte—‘ihre lezer in ungarn—šraybt er—und oyx die in daytšland verden es ihnen nixt ibel nehmen, vegn daytše špraxfehler unterloyfen zind, und geben zix geviss mit dem guten inhalte cu frieden’Footnote 26 (Shtern Reference Shtern1905, foreword)

By presenting this book to the public, I consider it my duty to state [the following]: In order to avoid criticism, I wanted to have corrections of language-mistakes printed at the end of the book. But a very respected rabbi (may his light shine) in Bavaria wrote me that he considers the publication of corrections highly unsuitable. “Your readers in Hungary”, he writes, “and also those in Germany will not blame you for having made mistakes in German, but will rather be satisfied with the valuable content [of your book]”.

An excerpt from the will of Abraham Pollak (a rabbi in Zsámbék, and later in Poughkeepsie and McKeesport in the US. Written before his death in Pittsburgh, 1934):

dir zugosi eyšes xayil [my wife, virtuous woman] danke ix fir dayne bezondere gute und oyfopferung fir mix, und unzere kinder yxi’ [may they live], du hast immer nur arbayt, und zorge gehabt an mayner zayte, fercayhe es mir, zay mir moyxl [forgive] den caar [sorrow] das ix dix gebraxt habe gegen daynen villen nach amerike, mayn kavone [intention] vahr cum guten. (Pollak 1967:11)

I thank you, my virtuous wife, for your unique goodness and your sacrifice for me and for our children, long may they live. You always had work and worries [living] by my side. Forgive me, forgive the sorrow caused by my bringing you to America against your will. My intention was a good one.

Germanized Yiddish (from the Unterland )

Excerpts from letters, written by Yekhiel Homoker in 1936-1940 to his son and daughter-in-law in New York (from Homok/Kholmok, a village near Satmar). Besides the Germanized orthography, the German-like characteristics used by this writer are mainly the sporadic use of German verbal conjugation (including preterite forms such as vahr, vahren (Ger. war, waren) and subjunctive forms such as hette (Ger. hätte)), and of German lexicon. Note that the orthography lacks the Yiddish diacritics, so that the writing of some elements allows for both a German-like and a Yiddish pronunciation (both options are given in the transcription). The Yiddish transcription represents the YIVO standard pronun-ciation rather than the pronunciation of the writer’s Yiddish, e.g. xosn ‘groom’ and tog ‘day’ (pronounced xusn and tug in Unterland Yiddish). The transcription follows the YIVO transliteration rules (with three modifications: [c] is used instead of [ts], [š] instead of [sh] and [x] instead of [kh]).

geliebte kinder n”y [may your light shine (long may you live)], fon yect virde ay”h [God willing] šrayben fir enk in yudiše špraxe dennox ix habe biz yect immer gešrieben blh”k [in the holy tongue] fir dir lieber zohn n”y [may your light shine] aber/ober fon yetct an/on gefangen befinde ix mix das/dos fer anderen, den ix volte das die liebes froy šti’ [may she live] zol oyx ferštehn vas/vos ix šreibe fir enk ci giten. […] lieber zohn n”y [may your light shine] die ferlofene voxen zinden vir zehr umbevist fon dayn lage – den dem brief vas/vos du hast/host gešrieben das di bist ayn xosn [groom] gevorn haben/hoben mir nixt bekommen biz cum haytiegen tag/tog oyx nixt …(Gross Reference Gross2004:164)

Beloved children, may your light shine. From now on, I will write you, God willing, in the Jewish/Yiddish language, after always having written to you, beloved son, may your light shine, in the holy tongue [Hebrew]. But from now on I would change this, since I want your beloved wife [my daughter in law], long may she live, to also understand what I write you (may they only be good things) […] Beloved son, may your light shine, during the last few weeks we were not informed about your circumstances, since we have not received, to this day, the letter in which you wrote that you got engaged.

liebe kinder […] mir haben/hoben bekommen šrayben fon enk […] das etc hate cu giten gekommen ayn xošev’n [important] gast ayn thayeres toxter šti’ [may she live] lmz”t [congratulations, may she have good fortune]. oyf diezen brief haben/hoben mir zo fort beantvortet in mir haben/hoben gehoft cu bekommen vayter šrayben fon enk das mir zollten kenen begrissen mit dem namen/nomen fon enker toxter šti’ [may she live], aber/ober biz yect habe ix gevartet in mir veysen nox alc nixt vi das/dos nayes geborene fraylene heyst cu gitin amo”š [may she live to be a hundred and twenty] (Gross Reference Gross2004:184)

Beloved children, we received your message […] that you happily received ‘a distinguished guest’, a dear daughter, may she live and have good fortune. We immediately replied to this letter, and we hoped for more letters from you, so that you would also write us more, so that we could congratulate you on the name of your daughter, may she live and be well. But I have been waiting to this day, and we still do not know how the new born missy is called (may her name bring her only good), may she live to be a hundred and twenty.

dieze voxe habe fon enk brief. oyx di cvey fotografyen erhalten, die fotografyen vas/vos mir haben/hoben zehr švehr gevartet […] gloybet mir liebe kinder das/dos herc tit mir veh das zo lange cayt haben/hoben mir nixt di zxyie [privilege] cu zehen zix mindlix layder, aber/ober mir mussen hofen cu ašy”t [The Lord] das es vird oyf diezen oyx kommen di cayt bekorev [soon] ay”h [God willing]. (Gross 2004:186)

This week I received letter/s from you, also received the two photos, the photos that we waited so long for […] Believe me, beloved children, my heart aches since we did not have the chance to meet in person and to talk for so long, unfortunately. But we must hope to the Lord that the time for this will also come soon, God willing.