Family Planning, a short, animated film made by Walt Disney Productions in 1968, is a touchstone for historians of global population. Since Matthew Connelly’s Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population re-energized the field, the film has become a fixture; an irresistible opportunity to namecheck Donald Duck and inject some levity into otherwise sober accounts.Footnote 1 Analysis has concentrated on salient features of the film: its construction of an ethnically generic ‘everyman’, its consumerist message, and its coyness about contraception. It typically figures as one of the most significant products of a sustained effort to mobilize mass media in the service of international family planning. The Marxist critique of Donald Duck as an imperialist emissary from around the same time has not escaped notice.Footnote 2 Details can be unreliable – the number of translations claimed, for instance, varies; one of the first scholars to encounter the film, in the US National Archives, presumed a white audience; and a more recent account has Donald painting images of birth control devices (he doesn’t) – but, otherwise, the substance is accurate enough: Family Planning was produced by Disney for the Population Council, an NGO created by John D. Rockefeller III in 1952, to promote the ‘nuclear family’ in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.Footnote 3 As part of a modernizing programme rooted in direct trade-offs between fertility, on the one hand, and family health, wealth, and happiness, on the other, it targeted the paterfamilias and argued that his capacity to adequately provide for his children, not the number of his offspring, should be the measure of his manhood.Footnote 4

Insights and errors notwithstanding, historical accounts of Family Planning largely draw on the film itself as evidence; scholars typically watch the film on YouTube to report and analyse its audio-visual content.Footnote 5 In this article, by contrast, we mobilize previously neglected lines of evidence held by the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC) and elsewhere to shed new light on consequential yet hidden processes of production, circulation, and reception.Footnote 6 In drawing from the materials at the RAC – and beyond – we aim to contribute to an increasingly concerted effort to embed questions about media and communication more centrally in global histories of reproductive politics.Footnote 7

Family Planning was a meaningful investment on the part of the Population Council, a major player on the international family planning scene; it was also a compromise with Disney, which then as now was one of the US film studios with the greatest international reach. As a historically significant and little investigated media object with a substantial paper trail, Family Planning presents a strategic opportunity for revisionism. Following the film, we argue, complicates the widely held assumption that by dint of its high production cost, translation into many languages, and global distribution, Family Planning was a highly successful tool in the effort to persuade local audiences of the safety and acceptability of contraception and the merits of small family size. In contrast, we demonstrate that faith in the universal legibility of Donald Duck – with his US origin and unintelligible speech – posed a problem for the ‘globish’ language of animation to which the filmmakers aspired.

Building on pioneering studies by media scholars including Kirstin Ostherr and Manon Parry, our analysis more specifically extends recent historical research by Savina Balasubramanian, and Emily Merchant. Footnote 8 As Balasubramanian and Merchant have persuasively argued, US social scientific theories and practices of mass communication became central to ‘post-Malthusian’ population control efforts in the Cold War. In the 1950s and 1960s, Frank Notestein’s demographic transition theory crucially shifted attention from the environmental constraints of food production to national economic development. In the effort to curb global population growth, he and other demographers associated with the Office of Population Research at Princeton and the Population Council championed mass communication as a powerful alternative to industrialization, which they perceived as proceeding too slowly to be effective in the poorest regions of the non-aligned world. Mass communication, in their eyes, could play the role industrialization had in earlier demographic theories; mass media took centre stage not merely as a handmaiden but as an engine of fertility decline in the absence of industrialization.

Closer to home, our study further builds on two articles recently published in this journal. The first, by Alexander Medcalf, investigates the World Health Organization’s postwar engagement with new media technologies and ‘public information’ strategies to educate people and help fight disease. Early failures and disappointments prompted the WHO to question whether its media expenditures were justified and to revise its strategies. Ultimately, Medcalf concludes, the WHO acknowledged the inadequacy of the ‘one-size-fits-all approach’.Footnote 9 Medcalf’s account aligns with those of a variety of attempts by international health organizations to construct and reach a newly imagined (and presumed illiterate) global audience.Footnote 10 Film was especially valued in this role, as Ostherr has shown.Footnote 11 And within types of film, animation was prized for its supposed capacity to be more comprehensible to diverse audiences – as we shall see for Family Planning.

The second article, by Nicole Bourbonnais, decentres high politics and (typically male) population experts to bring into view the more intimate everyday practices of mid-level (typically female) International Planned Parenthood Federation fieldworkers in the 1950s. As is well known, family planning grew into a multi-million-dollar international aid industry as it became entangled in Cold War and decolonization geopolitics and was powerfully challenged by the Catholic Church. As an international project of modernization that crucially depended on medical knowledge, technology, and personnel, the biopolitical mission of family planning shared general features with that of world health. Yet, the idea of promoting small family size and non-procreative sex was politically fraught, emotionally charged, and morally contested in specific ways. Bourbonnais finds a heterogeneous range of motives, ideologies, and communities involved – as does our analysis of Family Planning.Footnote 12

As an intervention in the field of global history, this article investigates the centrality of mass media and mass communication to the project of international family planning from the perspective of a range of actors. We expose some of the tensions, contradictions, and compromises that have been hiding beneath the surface of a ten-minute film. We show that Family Planning was in some respects in keeping with related films of the period. For instance, the Population Council set out to create a frank and detailed introduction to contraception, but struggled to balance narrative against didacticism, and ultimately censored (‘Disneyfied’) their own film. The film was also drafted into the anti-communist politics of the Cold War, and employed aesthetic strategies of depicting overcrowding that were in keeping with the genre. In other respects, however, Family Planning departed from its contemporaries: this was an ambitious attempt at creating a globally distributed and universally legible advocacy film that could speak to all publics. To this end, the film’s enormous budget embraced: (1) an unusually expansive multilingual release, with at least two dozen versions existing in various languages; (2) an intermedial production strategy, with the film itself as just one component of a media suite that included comic books, flipcharts, and slides; and (3) a distinctive distribution programme that relied on not only existing infrastructure but also more informal and ad hoc modes of transportation and screening. Despite the resources poured into the film and perhaps contrary to present-day expectations, Family Planning, we argue, failed to connect with local audiences.

The Population Council and mass communication

The history of the Population Council (PC) is well documented.Footnote 13 For our purposes, it is important to note that it emerged as a global leader in family planning in the 1950s, as national governments, NGOs, and the UN increasingly allocated resources to the perceived problem of world overpopulation, the famine and hardship it was predicted to cause, and, not least, the potential for communism to take root in India and other poor countries with already large and rapidly growing populations. Family planning, an ascendent term for a highly personal, politically, and religiously sensitive topic that encompassed contraception and was often conflated with population control, was the proposed solution.Footnote 14 The idea behind its internationalization was to modernize family size and reestablish demographic equilibrium in a postwar world where scientific and medical progress had effectively reduced infant mortality (‘death control’) but not fertility (‘birth control’).Footnote 15 In the absence of industrialization, this required new methods of contraception, distributional infrastructures, educational campaigns, and cultural change on a mass scale. To these ends, the PC invested in four key areas: (a) advisory assistance on family planning to poor-world governments; (b) contraceptive R&D; (c) demographic data collection, evaluation, and training; and (d) information exchange. Most famously, the PC developed, tested, and distributed a new generation of less expensive plastic intra-uterine device (IUD).Footnote 16 Nor was communication left to chance. To facilitate the circulation of knowledge, the PC launched a journal, Studies in Family Planning, in 1963, established a circulating film library in New York, and created ‘prototypic aids that could be adapted to the needs of particular countries’.Footnote 17 Of the aids, Family Planning represented the PC’s single largest investment; it was also a compromise with Disney.

In many ways, Family Planning was the product of the still-young field of mass communication, a US academic specialism within the social sciences that coalesced as behaviourist experts in wartime propaganda found peacetime applications for their research on techniques of large-scale public information and persuasion. The Cold War concern that rapid population growth in poor countries would destabilize nations created new employment opportunities and resources for enterprising pioneers of mass communication. As a specific kind of expert, they endeared themselves to the international family planning establishment by persuasively arguing that the availability of new contraceptive technologies was not enough; governments and organizations needed to engender cultural change on a mass scale and this could be achieved only through effective communication. Footnote 18 Several key figures, including Bernard Berelson, who was heavily involved in the production of Family Planning, cut their teeth at the University of Chicago’s trailblazing mass communication programme. He joined the Ford Foundation in 1951 and a decade later was directing the PC’s new communication research programme. Footnote 19 Berelson’s work epitomises the meeting of mass communication and family planning.

In this role Berelson was concerned to extend ‘research on the role of mass communication in shaping men’s reproductive attitudes’. Footnote 20 Experts, including Berelson, claimed that the use of mass media in and of itself created the impression of general social acceptability and normalization, a key goal of family planning campaigns. Publicity on a mass scale, they maintained, could demystify and destigmatize a sensitive topic that was taboo in many cultures.Footnote 21 With Family Planning, Berelson set ambitious goals for the strategies of mass communication to ‘popularize, legitimize, motivate for, and “sell” family planning throughout the world’ (Figure 1). Footnote 22 Family Planning pushed the boundaries of communication around the delicate subject of its title.Footnote 23

Figure 1. A poster for Family Planning included in a promotional pamphlet for the film distributed by Disney, with a rationale for the film attributed to public health experts, as well as a birth control focused bibliography. PCR, RG2, FA432 54, box 519, folder 4809, RAC.

As the PC explained in January 1968 in Studies in Family Planning, the Disney film ‘makes about 15 elementary but important points about family planning’.Footnote 24 It opens with a disclaimer: ‘The characterizations and situations used in this film may not apply directly to your community, but the basic problems presented are of concern to people everywhere’. This tension, between a disparate global audience and, we argue, an ultimately misplaced faith in the universal appeal of Donald Duck, would persist as the film circulated far and wide.Footnote 25 The disclaimer cuts to the inverted red triangle – the iconic symbol of India’s family planning programme – illuminated by a spotlight shining on a red curtain, a backdrop for a stage. The triangle contains an Isotype-style depiction of a nuclear family: mother, father, girl, boy.Footnote 26

About a minute in, the curtain opens and Donald Duck rushes on stage, easel in hand. His clumsiness in setting it up provides comic relief, while the more sober voice-over introduces the subject of the film: ‘Man’. This narrator then introduces the ‘Common Man’, who is visualized as an amalgamation of various ethnicities and cultures from around the world; and then ‘Woman’, explaining that the ‘upward rise’ of Man is being slowed by the ‘sheer rate of numbers’. We learn about the historic ‘balance’ between births and deaths, especially of young children, until recent progress in medicine, science, and sanitation disrupted the age-old equilibrium. As a result, families are becoming larger and poorer. This is depicted by way of example: a small, healthy, happy family that can also afford a radio, is contrasted with a large, sickly, miserable family that is barely able to feed itself. Donald transforms into a doctor, complete with white coat, medical bag, and head mirror, as the narrator explains that ‘modern science’ has provided the ‘key’ to a ‘new kind of personal freedom’: family planning.

The final third of the film does not get into the nitty gritty of contraception, but coyly explains that family planning means the freedom to ‘have only the children you want, and when you want them’. Gradually winning over the initially sceptical everyman, the narrator discloses the existence of ‘several effective methods’, including ‘pills’ and ‘simple devices’. The Woman, who doesn’t speak for herself, but whispers in her husband’s ear, asks if the methods are acceptable and safe. The narrator reassures them that the methods are not only safe, but improve the health of mother and children. The measure of a man, in turn, is not the number of children he has, but how well he takes care of them. ‘And all of us’, the narrator intones as Donald, imitating Uncle Sam, points directly at the viewer, ‘have a responsibility towards the family of man, including you!’Footnote 27 The curtains draw closed.

Pre-production: the why, the what, the how

While Family Planning was in pre-production, Walt Disney Productions was segueing from an ambitious postwar slate of films that have become classics (Alice in Wonderland, 1951; Peter Pan, 1953) to a subsequently less well-regarded, more economical model of production that would abide through the late 1960s and 1970s (Jungle Book, 1967; Robin Hood, 1973). Fans sometimes refer to this as the shift from the Silver Age to the Bronze Age of Disney films, reflecting a perceived drop in quality that is often associated with the passing of Walter Elias Disney 1966.Footnote 28 At the same time, using models of for-hire production that Disney had developed while making propaganda during the Second World War, the studio made educational and industrial films for a variety of institutions and companies, including the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, Kotex, and Upjohn. Footnote 29

Disney, the man, did not live to see the completion of Family Planning, but an early meeting between him, Bernard Berelson (again, head of the PC’s Communication Research Program), and Raymond ‘Ray’ Lamontagne, a friend of Rockefeller’s son Jay, occurred in the months prior to his death. In March 1966, Berelson recorded that he and his colleagues were ‘impressed’ with the Disney staff, and that Ken Petersen (a long-time animator and producer for Disney, and then ‘head of the 16mm documentary work’) had ‘“fallen for” the population problem and wanted to get in on it’. Footnote 30 There is some evidence that Disney himself was concerned with overpopulation. In 1964, he had contributed to Golden Opportunity, a short advocacy film concerned with the impact of population growth on California’s natural environment.Footnote 31 Possibly gifted by the PC in preparation for their collaboration with him, he kept a copy of Family Planning and Population Programs, the proceedings of a 1965 conference edited by Berelson and others, in his private office.Footnote 32 And he proposed a (later discarded) premise for what would become Family Planning, ‘having to do with an analogy in animal reproduction’.Footnote 33

Another principal area of discussion at the meeting was what – of the many possible topics that fell under the banner of population control – should be emphasized in the film (or films; a trilogy was considered). As Berelson framed it, should Family Planning focus on ‘the Why (rationale for family planning), the What (physiology of reproduction), [or] the How (contraceptive methods)’.Footnote 34 There was disagreement. Disney staff argued that ‘what’ and ‘how’ had more sales potential. The PC, meanwhile, advocated for ‘why’ an editorial stance that aligned with its broader objectives. For one thing, the Council’s demographic paradigm held that if the ‘why’ were in place, the ‘how’ would follow. For another, the Council concentrated its promotional efforts on the IUD, a female method, but the film primarily addressed men. These fundamental questions of emphasis and goals would bedevil Family Planning in pre-production and beyond.

The potential risk of fallout from depicting ‘what’ and ‘how’ – which is to say procreation and contraception – even euphemistically, in an animated film was not addressed as a meaningful topic. As Berelson recalled, ‘The question of whether Disney should back off from this possibly controversial subject in his own commercial production never really came up. It was skirted once, but dismissed. He doesn’t seem worried about it, to my surprise’. Footnote 35 Disney, the man, officially disavowed politics and insisted that his studio was nonpartisan.Footnote 36 As one critic framed it, in reference to the Disney sexual educational film VD Attack Plan (1973): ‘The corporation is determined to keep separate their educational and entertainment branches. The two images, they believe, clash. VD and Snow White simply do not mesh’.Footnote 37 Many scholars have demonstrated how porous this separation was, in fact, and have characterized the historic politics of the studio – imperialist, capitalist, reactionary, quietist – not to mention the material evidence that shows Disney participating in many political minefields in the decades preceding and following Family Planning.Footnote 38

In any case, the plans for ‘how’ were, for much of the pre-production process, quite detailed. Into July 1966, the film was still to include up to ten minutes regarding ‘Information on Contraceptives’ in which ‘the loop’, the plastic IUD developed by the PC, as well as ‘sterilization, condom and the pill’ would be described, with a strong emphasis that contraception ‘doesn’t interfere with your pleasure’. As for ‘the nature of human conception’, the goal was to include ‘only enough to establish our bona fides. Don’t go into detail’.Footnote 39 Comparatively, at this stage the ‘why’ – ‘The Population Problem’ – which would ultimately prove central, received short shrift, only five planned minutes of a longer intended runtime. Footnote 40

The debate is further evidenced in the project’s shifting title. In informal, internal usage, PC staff typically referred to The Population Picture, allowing for a capacious perceived focus; or The Disney Film, showcasing their collaborator. In 1967, the working title was The Family of Man, capitalizing on the celebrated Edward Steichen exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955, and its popular accompanying book. Footnote 41 Perhaps hewing too close to the exhibit and risking conflation, they then reversed the title, opting for Man and His Family. Language that refers to this formulation is maintained in the film’s final script. Finally, as late as August 1967, Disney’s Carl Nater – who had worked on educational films for the company since the Second World War – advocated for the more direct Family Planning, which ultimately prevailed. Footnote 42

This title posed its own problems, however, and discussion of it sometimes revealed the low regard that the PC staff had for the film’s intended viewers, namely, the ‘low literacy, low income, uninformed audiences of men and women of reproductive age in the developing world’. Footnote 43 In an internal list of ‘problems we have to deal with in making the picture’, one PC staffer worried that for the imagined viewer, ‘the idea of “planning” is a foreign notion. We live in the future – they live in the present only’. Footnote 44 A further concern was that ‘family planning’ would be misinterpreted as synonymous with abortion. The PC thus wished to emphasize different methods in the film, contraceptives that existed ‘in various forms that are suitable to every cultural and religious group. There is an acceptable way for everyone, i.e., for you’. PC staff emphasized that the film should ‘illustrate and make the definition clear, i.e., family planning is not abortion’. Footnote 45

The ‘why’, ‘what’, ‘how’ debate often overshadowed more prosaic questions about the film as entertainment. How was a Disney animated short meant to convey the idea of overpopulation, discuss the physiology of reproduction, and introduce contraceptive methods without causing offense and still be entertaining enough that culturally diverse audiences would willingly pay attention?Footnote 46 PC staff had hoped that the ‘why’, ‘what’, and ‘how’ could be conveyed within the context of a story. However, per an internal complaint in late 1966, they perceived Family Planning as ‘not a bad animated lecture but it should have been an animated drama’. Footnote 47 The relative weight of drama versus lecture in Family Planning would continue to hang over the film during its production process. To shoulder the burden: Donald Duck.

Production: Homo Quackus

In a Disney treatment for Family Planning from October 1966, screenwriter William Bosche outlined an alternate plan that made Donald Duck even more central to the film:

-

5) ‘This’ – says the narrator, ‘is the creature who dominates all the rest – Homo Quackus’.

-

6) Don reacts rather smugly as the narrator says that he and his kind are beings of great ability and unconquerable will – capable of building mighty edifices or unlocking the secrets of the universe.

-

7) ‘But’ – says the narrator, ‘there’s one thing wrong. Quackus is reproducing himself so fast that everything he has achieved may be lost through over population’.

-

8) Now the duck becomes two – then a group of four. This group doubles – and doubles again and again until the screen is covered with identical Donald Ducks. Footnote 48

This unmade version of Family Planning, with its exponential surrealism, mirrored the aesthetic techniques and communication design of contemporaneous overpopulation advocacy films. One strategy that filmmakers frequently used was to depict crowding, an approach that live-action films, including Z.P.G. (1972) and Soylent Green (1973), struggled with due to the high cost and logistic complexity of filming a large number of tightly packed extras, usually from above, but which animation, like illustration, could overcome.Footnote 49 This technique, which aims to elicit a sense of agoraphobia in the viewer, was specifically targeted by Population Council staff, who at an early stage suggested that the film show ‘the problem of crowding – the panic grows, the music becomes faster and more frenzied, etc.’. Footnote 50 Ultimately, while Homo Quackus, panic, and frenzied music were abandoned, the image of exponential human growth was maintained, albeit set to whimsical music and a benign voiceover (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Screenshot from Family Planning depicting the exponential growth of humankind. The voiceover intones: ‘The family of man is increasing at an astonishing rate, almost doubling every generation.’

So, too, was Donald Duck maintained. The PC saw their success in obtaining this character as their messenger as something of a coup, and promised to ‘assist in seeing that Donald Duck’s message gets maximum exposure’. Footnote 51 (The PC typically used Donald’s full name even amongst themselves, whereas the Disney staff would sometimes use the more familiar ‘Don’, as in the ‘Homo Quackus’ treatment.) During the war, Donald Duck had been a fixture of propaganda films ranging from the Academy Award-nominated The New Spirit (1942, on which more below) to the dystopian, now-cult film Der Fuehrer’s Face (1942). After the war, he continued to star in educational films, including a safety series that began with How to Have an Accident in the Home (1956). In Family Planning, he was brought to screen by William Bosche, who wrote the treatment above and was the listed screenwriter for the final film, and the director Les Clark, who had been with Disney since the silent era. Clark and Bosche worked together on educational shorts for Disney in these years, including those mentioned above for Upjohn pharmaceuticals, Steps Toward Maturity and Health (1968), Physical Fitness and Good Health (1969), and The Social Side of Health (1969).

Simultaneously, the Council had a sustained engagement with film production beyond Family Planning. Just as Disney produced informational films for a range of clients, including those for Upjohn, so the Council contracted films from a range of studios. Two versions (with surgical gloves for ‘domestic’ audiences, without for ‘overseas’ viewing) of their short instructional film, New Intra-Uterine Plastic Contraceptive Devices (1963), circulated widely to positive responses and were much in demand from Fresno to Delhi.Footnote 52 In this context, Family Planning can be seen as a culmination of increasingly ambitious and expensive attempts to mobilize the medium of film. Indeed, a single donor gave $400,000 to help make and distribute Family Planning, an enormous amount for an educational film. Footnote 53 Throughout 1967, Clark and Bosche were frequently in correspondence with Harry Levin, Director of Informational Services with the PC, who would go on to handle the film’s distribution.

During the production process, two central issues stimulated much of the internal discussion around the direction of the film. First, there was once again concern about the absence of the ‘how’ (contraception) and the ‘what’ (procreation) in the film; concern that was compounded with worry about how depicting these might impact the reputation of Disney Studios. Second, there was an abiding anxiety regarding the international relatability of Donald Duck as the face of family planning. These concerns about reputation, and the tailoring of the everyman, would continue well after the film was nominally ‘finished’ – because, indeed, with its ongoing translations and global distribution patterns, the film remained in flux for longer than most.

The worry about Disney’s reputation is not what might be supposed; the concern was not that, in depicting, for instance, procreation or contraceptives, the family-friendly reputation of the studio would be tarnished. Indeed, Disney–Upjohn’s Steps Towards Maturity and Health, mentioned above, depicts procreation more frankly than Family Planning, and thus makes for instructive comparative viewing (Figure 3). On the contrary, the worry for the PC was that Disney would make the serious matter of overpopulation too cute, and too sanitary. From the outset, the PC sought out Disney because the ‘organization is identified throughout the world with wholesome family life and thus, in effect, its imprimatur is given to family planning’. Footnote 54 But might not this turn into a problem? PC staff worried that ‘even though we have a veto on content, the film could get out of hand in presentation (too “pretty”, too “funny”, too Disneyfied)’. Footnote 55 In the event, the PC were more circumspect than Disney in terms of what might be included in the film. It was the PC who advocated for only ‘why’, whereas Disney had made the case for ‘how’ and ‘what’. And it was Disney who had advocated for the more direct title, Family Planning, in lieu of the circumlocutional Man and His Family.

Figure 3. Screenshot from the procreative section of Steps Towards Maturity and Health (1968). Voiceover: ‘In the body of a female, an egg cell called an ovum comes together with another kind of cell called sperm, produced by the male.’

A film such as Family Planning, with its intended global audience needed to be as relatable as possible to different groups. By this stage, many thought animation was key in such cross-cultural messaging, a kind of Esperanto for the screen.Footnote 56 Because animators, as Walter Disney framed it a decade earlier ‘can’t take refuge in words’, they must ‘talk straight in the world’s oldest language – pictogaphs – things the eye instantly comprehends and transmits to the mind’.Footnote 57 This would allow ‘the most direct address to great masses of people who could be benefited and enlightened by what we could very simply visualize on the screen’.Footnote 58 It is for this reason that, as a Disney spokesman explained at the film’s release, ‘Donald himself does not speak in the film’. Given the film’s intended audience, and the fact that ‘many people say they cannot understand him’, the speech is left to the off-screen narrator, which was more easily replaced in translation.Footnote 59

Having abandoned Homo Quackus, Disney and the PC had by the time of the film’s production settled on an ‘everyman’ stand-in, a man who might belong to any culture. While stereotypes of different cultures and nations would be depicted in brief sequences at the beginning and end of the film – premised, Harry Levin reported, on ‘slides which were provided to us by the United Nations as a guide’ – the majority of the film would rest on characters known internally as ‘Mr. and Mrs. Common Man’. Footnote 60 By 1968, the everyman was an established character in a genre that would become known as the ‘animated documentary’.Footnote 61 But, as film scholar Cristina Formenti has noted, versions of the everyman character had already appeared in animated advocacy films from the United Auto Workers’ Brotherhood of Man (1945) to the American Cancer Society’s Man Alive! (1952). More proximately, he also starred in A Great Problem (1960), an advocacy film about overpopulation produced by the Film Division of India, and which may have provided a template for aspects of the Disney film.Footnote 62 In each, as in Family Planning, the everyman is to ‘whom the voice-of-God or voice-of-authority narrator imparts a lecture’.Footnote 63

At this stage, the film’s makers and producers were largely unconcerned with how imagined audiences around the world would respond to Mr. and Mrs. Common Man. In contrast, they fretted over the reputation of Donald Duck during the film’s production. Part of this concern stemmed from the conclusion of the film, in which the PC asked that Donald Duck ‘look right at the audience and say something like: “Including you!” or “It’s up to you!”, pointing his finger at the audience. This would also provide some identification of Donald with the message of the film’ (Figure 4). Footnote 64 The final image and script are clearly referencing First World War propaganda posters; specifically, the image of Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer with text that reads ‘I want you for U.S. Army’.Footnote 65 This poster, which by most estimates had a print run of four million copies, would have been a widely, if not necessarily globally, known illustration.

Figure 4. Screenshot from the conclusion of Family Planning. The versions of the film that we have accessed conclude with the voiceover line, ‘All of us have a responsibility toward the family of man. Including you!’

This proxy association of Donald Duck with the US federal government (embodied by Uncle Sam) was not ideal. Donald Duck had during the war been the lead in Disney’s collaboration with the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs for South America. During this time, Donald Duck had to some extent taken over from Mickey Mouse as the principal Disney character in the animated shorts. The character had been the locus figure of what film historian Eric Smoodin calls the ‘Donald Duck Debate’, regarding the wartime propaganda film The New Spirit (1942). The US government had paid $80,000 to produce the film (a figure many regarded as exorbitant), which encouraged the routine paying of taxes to support the war effort.Footnote 66

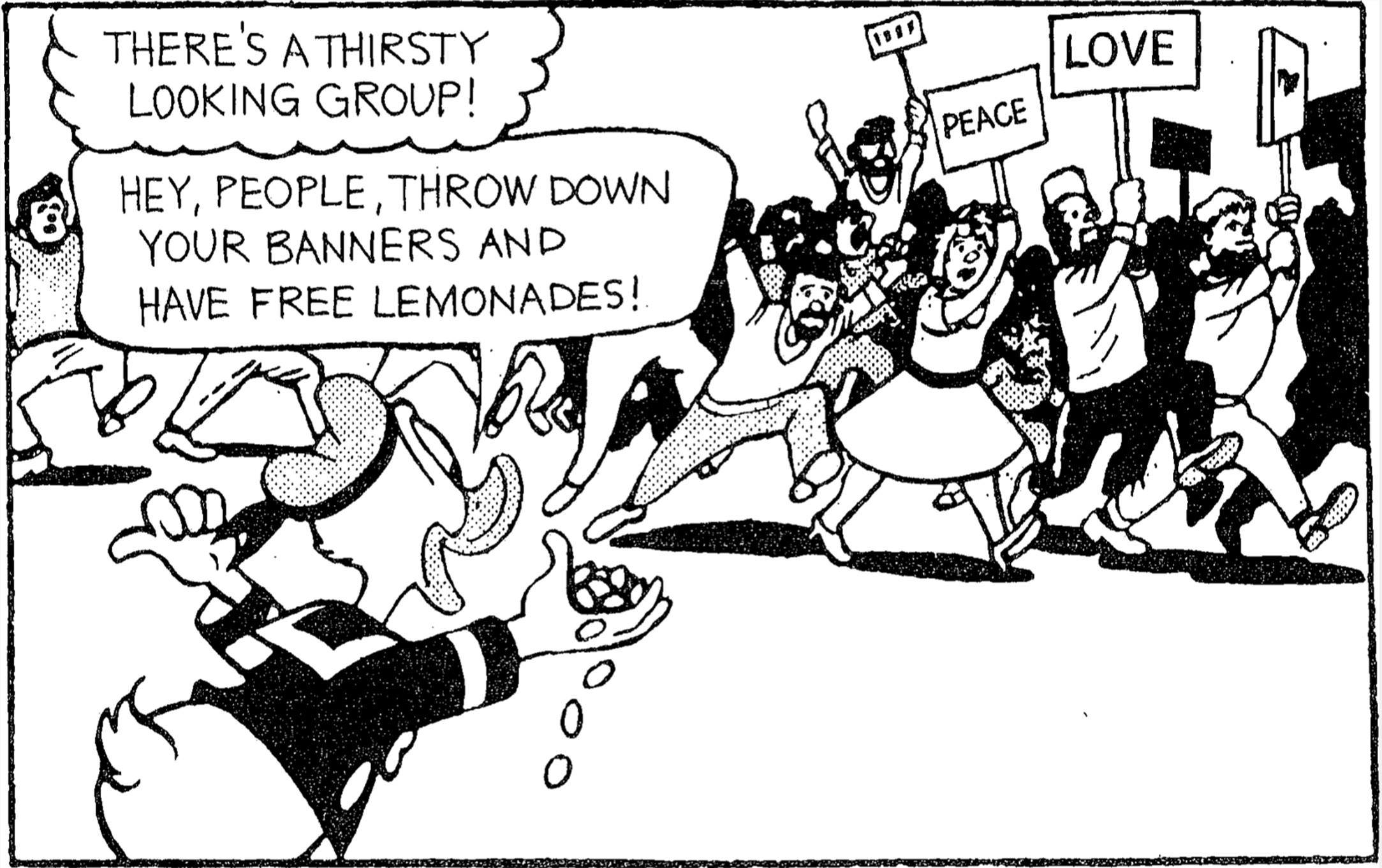

Donald Duck was already a target for ideological critique, especially following the Disney animators’ strike of 1941.Footnote 67 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno wrote of him in the early 1940s as a kind of Fordian, culture-industry scapegoat figure: ‘Donald Duck in the cartoons and the unfortunate victim in real life receive their beatings so that the spectators can accustom themselves to theirs’. Footnote 68 In the 1960s, Disney came to be figured as a ‘Henry Ford of media’, with all that that entailed – including a reputation for an undifferentiated industrial product and mistreatment of workers.Footnote 69 Not long after the release of Family Planning, Donald Duck’s reputation as an imperialist would crystalize in Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart’s Marxist analysis, How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic, first published in Spanish in 1971 and subsequently translated into more than a dozen languages. Donald Duck was a kind of stand-in for US cultural hegemony (Figure 5). Indeed, Dorfman and Mattelart conclude the English preface to their book with an order: ‘Donald, Go Home!’ Footnote 70

Figure 5. How to Read Donald Duck used, among other techniques, close readings of individual scenes from Disney comics. In this panel, Dorfman and Mattelart criticize the depiction of ‘“hippies”, “love-ins”, and peace marches’, as ‘a gang of irate people (observe the way they are lumped together) march fanatically by, only to be decoyed by Donald towards his lemonade stand’. The implied moral lesson: ‘see what hypocrites these rioters are; they sell their ideals for a glass of lemonade’. How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (New York: International General, 1975), 55.

Population Council staff were aware of this reputation, and worried that it might conflict with their efforts; they already fought perceived associations with the US government. They debated ‘the use of the “white” duck’; but reassured themselves that Donald was recognized as a Disney character the world over, and that ‘no racial overtones would be read into it’.Footnote 71 During production, they wondered if there was ‘any evidence of the larger ideological argument that perhaps through this film … Westerners are trying to keep the rest of the world in a contained manageable situation’. Footnote 72 Newspaper coverage reaffirmed this understanding; the headline of one report on Family Planning simply reads, ‘Donald Duck will Lecture Asians on Over-Population’.Footnote 73 Apparently unaware of A Great Problem (1960), The Times of India suggested that, instead of relying on a ‘private U.S. family planning body’, the Films Division of India could make its own ‘cartoon documentaries’ on family planning.Footnote 74 Archival records give some credence to these suspicions. For instance, a Disney staffer suggested that ‘in the interest of keeping the number of communists in the world down to the lowest possible level perhaps the Population Council would like to donate a print’ to the people of East Germany, to which Levin replied: ‘Even in whimsy, the Council is not dedicated to keeping down the numbers of any specific group in the world for any reason whatsoever’. Footnote 75

The PC were between a rock and a hard place: Donald Duck was internationally famous but would always have, as an internal memorandum phrased it, a ‘substantial association with the United States’ and worse, a reputation as a ‘Yankee Imperialist spokesman, if not stooge’. Footnote 76 One ameliorative strategy was to mute Donald and translate the narration into diverse languages. At great cost and effort, this was attempted.

Translation and distribution: paperwork headaches

The Population Council’s ambitious goals for distribution, especially to presumed illiterate audiences, required the translation of Family Planning into many languages. Indeed, the translation agenda for the film was surely one of the most ambitious for any educational film in the genre’s history.Footnote 77 It was translated into at least twenty-four languages, with plans for more.Footnote 78 For context, one would have to venture back to the silent era to find a film even approaching this number of translations; at that time, the fact that there was no spoken, synchronized dialogue meant that film intertitles could be easily and cheaply translated. Meanwhile, in the sound era, a film renowned for its number of non-English sequences, Paramount on Parade (1930), was modified into just nine languages. In general, as film historian Donald Crafton notes, the typical producer’s presumption was a ‘confidence in their audiences’ willingness to accept English’.Footnote 79

Animation, like silent film (and for the same economic and technical reasons), was understood to be a medium that communicated in a universal language.Footnote 80 Non-verbal, gestural forms of communication, delivered via slapstick or pantomime, involved sound effects that did not require translation. It is no wonder that mass communication as a discipline favoured animation, given the perceived need, as Kirsten Ostherr has noted, for a ‘“universal” language of international communication’.Footnote 81 More pragmatically, animation posed none of the same difficulties in synchronizing lip movement to speech (especially if your character was Donald Duck); and hiring an anonymous narrator was more affordable than hiring trained voice actors. Nevertheless, translations were an expensive process, materially; the PC paid ‘approximately $1000’ each time ‘to have the film dubbed in a foreign language by the Disney studio’.Footnote 82 And this did not include paying the translator.

The process of translation is instructive; from it we learn much about the informal support networks and backchannels on which translation relied. Usually, the task of finding a translator was outsourced to members of the PC stationed in the given country. Sometimes, the services of professional translators were secured (as in the Malay translation).Footnote 83 In other instances, local government would perform the translation; as a PC staffer phrased it, ‘the wheels of government have clanked and sputtered and, after liberal lubrication, have come forth with Urdu and Bengali versions of the Disney script’.Footnote 84 Most frequently, however, translations were ad hoc. The Tunisian script was produced by a linguist, ‘a Tunisian who has lived in the States and is married to an American girl’.Footnote 85 The Turkish script, sourced by John K. Friesen, of the PC’s Ankara division, was translated by his ‘secretary Vicki’s husband’.Footnote 86 This eclectic collection of translators, distinctive though it may have been to Family Planning, was in its range typical of translation in the history of reproductive knowledge, more generally.Footnote 87

When it came to distribution, during the film’s production in 1967, the PC had hoped that Disney would assist: ‘we intend to turn Disney loose on pharmaceutical firms and any other businesses directly connected with this field in the hope that they will purchase some number of prints’.Footnote 88 By the end of that year, it was clear that Disney could not be relied on, having ‘little or nothing to offer’ in that regard.Footnote 89 Indeed, relations with the studio were increasingly strained regarding matters of distribution throughout 1968, as a series of testy letters with Carl Nater at Disney make plain. The number of prints and films in translation, and their various licensing and promotional arrangements, caused a bureaucratic headache for Nater. He cautioned Harry Levin that ‘we’re going to have to work very carefully on all the bits and pieces of this film project otherwise our respective record-keeping is going to get out of hand’.Footnote 90 Out of hand, it got: Nater went from feeling ‘completely unenthusiastic’ regarding sample print distribution to ‘strangled by open paperwork’ tied to the prints.Footnote 91 Delays, erroneous shipments, and communication problems built up, leaving Nater with little hope of resolution. ‘Today’s mystery is now officially cleared up. Watch for next week’s exciting installment’.Footnote 92

The PC also relied on allied ‘population groups’, including the Pathfinder Fund, Planned Parenthood, and World Neighbors, as well as a number of governmental and health organizations.Footnote 93 While networks existed for circulating educational films, each film had to forge its own path given the topic and target audience.Footnote 94 Per PC records, in October of 1968 there were at least 1,500 prints in circulation.Footnote 95 When possible, they kept track of how many people viewed the prints. By March 1970, a total documented audience of 1,382,239 had seen Family Planning.Footnote 96 Some of the larger national figures include Taiwan, where 684,156 people had viewed the film; Ceylon, 385,014; and South Korea, 183,520 (Figure 6).Footnote 97 These figures omit the 8mm version of the film, not to mention the intermedial kit of comic books, flip charts, and other artifacts that Family Planning toured with, and which served to promote the film in locations where there was ‘no electrical outlet or generator’.Footnote 98

Figure 6. Also circulating: a foldable form-letter for those who screened the film to report on where and when it was screened, and how many people were there. ‘Family Planning 35mm Monthly Film Report’, PCR, RG2 AC2 54, box 520, folder 4813, RAC.

Other records contain hints as to how the film circulated as part of larger multimedia campaigns. For example, a report on the national family planning programme of South Korea for 1969, cites a two-month showing of Family Planning at an ‘exhibition center of a popular park in Seoul’ to audiences of some 2,000 viewers on weekdays, 10,000 on Saturdays and Sundays, for a total of around 114,000. An inventory in the same report lists fifty-five copies of the film alongside more than two million pamphlets on the loop and pill, as well as newsletters, booklets, pelvic models, flip charts, exhibitions, nineteen copies of another animated film (Tomorrow’s Happiness), 130 radio broadcasts, forty-three television shows, full-page ads for the loop, pill, and vasectomy in ten monthly magazines, and even one hundred thousand fans with a ‘family planning message’ for mothers’ clubs and tea rooms. Distribution peaked during ‘Family Planning Month’, which spanned April and May to overlap with Health Month, Mothers’ Day, and Children’s Day. A drama series promoting smaller families ran on the Korean Broadcasting System for the entire month of April and ‘elicited 1,000 letters’.Footnote 99

In Taiwan, in 1970, to give another example, the Department of Public Information showed family planning slides on island-wide television stations daily for three months, provided one-minute spots on all seventy government radio stations, produced a ‘new family planning film’, and screened Family Planning and another film (Happy Family) to more than 1.25 million viewers in ‘free rural film shows’ on programmes that included films on rural development or traffic safety; the Disney film screened at ‘every commercial theatre on the island (500 theatres)’.Footnote 100 And in the Isfahan province of Iran, a six-month media campaign starting in August 1970 included radio spots, leaflets, banners, news items, interviews, talks, mass mailings to professionals and postpartum women, press releases, a film clip produced by a Tehran-based company specialized in ‘advertisements shown at movies prior to the feature’, twenty exhibits, and a travelling ‘sound truck’ that played an 18-second message. Five prints of the Disney film screened at the largest of fourteen cinemas, where they were viewed by an estimated 225,000 people. About half of the one hundred people subsequently interviewed ‘on the street’ claimed to have seen the film and ‘liked it; the only criticism heard was that there was too much contrast between the small and large family’.Footnote 101 The Council further solicited information concerning how audiences responded to Family Planning.

Audiences respond: the limits of universality

After its release, Family Planning won at least two awards, one at the Columbus Film Festival and another at the Industrial Film Festival.Footnote 102 Although the Population Council purchased two plaques to mark the occasion, internally they were not preoccupied with film festivals or their awards. Nor was Disney; Carl Nater drolly made the case that such awards were merely ‘a nice way to feed the ego of sponsors’ and allow them to boast that the film ‘has won such and such an award in Cleveland’.Footnote 103 The PC were, however, preoccupied with audience reception.

As film scholars well know, it can be difficult or even impossible to recover the experiences and perceptions of past audiences, especially beyond the critics who wrote about films. But there are ways to circumvent this obstacle, and it is important to try.Footnote 104 In the case of Family Planning, we are fortunate that the PC circulated questionnaires for (literate) audiences to complete which provide evidence of reception. The council wished to know if viewers understood the overall message of and various symbolic imagery deployed in the film. For instance, the form developed for a Tunisian audience, asked: ‘What does the key represent in the film?’ and ‘How was family planning defined in the film?’Footnote 105 There were related concerns regarding the length and excessive comprehensiveness of the questionnaire, and how this might impact audience response. In a memorandum from March 1970, an unidentified PC staffer complains that the questionnaire was ‘much too long for persons leaving a cinema and anxious to be elsewhere. Have you ever suffered from public questionnaires? I have been inveigled into being a respondent at London Airport on at least three separate occasions and I can testify to the irritation it arouses if one is held up for more than five minutes’.Footnote 106 The commentor, here, assumes that the film will be screened in a cinema, but that was not invariably the case. Family Planning was shown in, among other venues, the classroom, the village, and the postpartum floor of a hospital (Figure 7).Footnote 107

Figure 7. A ‘motivational program’ in support of Family Planning in San Carlos City, Philippines, 23 February 1971. PCR, RG2 AC2 54, box 519, folder 4804, RAC.

Meanwhile, debates concerning translation, representation, and audience tailoring that had occurred during the production of the film continued until well after it was nominally complete. In the Philippines, for example, a ‘group of college-trained social workers’ reportedly ‘had difficulty following the meaning of the English soundtrack. Clearly, this version will not be very comprehensible to the bulk of our target population.’Footnote 108 Requests were made to alter specific translations, and for more substantive modifications. In one unusual case, Harry Levin individually toured a copy of Family Planning through ‘Lima, Rio, Asunción, San Salvador, San Jose, and Bogotá’. He requested a number of changes to the film, using quotes from local advocates for the film:

-

1) ‘We would prefer some other title than family planning, and wouldn’t it be possible for us to tone this down to something like family well-being?’

-

2) ‘The film is too much associated with India, and can’t we cut out some of the parts such as those showing the starving Indians?’

-

3) ‘This is the Indian version of the film, where is the one for Latin America? After all, this shows Indian starvation, buffaloes, and the red triangle symbol and will not identify with our people.’

-

4) ‘It tends to downgrade women as the woman talks only through the man.’

-

5) ‘They will not identify with the composite man and will think that the entire film applies to someone else.’Footnote 109

Latin American commentators, it seems, did not identify with the people or situations depicted in the film, which they perceived as intended for South Asian audiences, and they resisted its sexist implications.

Beyond the concentration of questionnaires and surveys performed by the PC, crucial evidence, including of circulation and reception, can be gleaned from other sources. Historian Nicole Bourbonnais kindly shared with us the most pertinent passages from the diaries of Dr. Adaline Pendleton (‘Penny’) Satterthwaite, a ‘midlevel technical advisor who traveled to over two dozen countries for the PC from 1965 to 1974’.Footnote 110 From these sources we learn that the red triangle, India’s family planning symbol, caused trouble and held up distribution in the neighbouring rival Pakistan. Though it proved technically difficult to replace with Pakistan’s preferred symbol for family planning, members of the Sweden Pakistan Family Welfare Project apparently managed to cut the objectionable shape from the Urdu version for TV Lahore broadcasts, where it was ‘very well received’.Footnote 111 A few months later, fifteen copies of the Urdu translation were in circulation and the ‘problem with the FP symbols’ had apparently ‘been forgotten’.Footnote 112 On the other hand, and despite the imagined universal appeal of Donald Duck, a Karachi doctor reported disappointing results with an accompanying filmstrip; the ‘idea of animals talking and painting pictures’ was, he claimed, ‘completely foreign’ to the scores of ‘illiterate’ women who were shown the filmstrip at an antenatal clinic and (supposedly) ‘didn’t understand it at all’.Footnote 113

In the early 1970s, Stanford Danziger, a Senior Fellow at the East–West Communication Institute in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, directed the production of a how-to manual on adapting educational materials to specific audiences with a filmstrip based on Family Planning as proof of concept. The filmstrip, a much-employed educational tool, especially where motion picture projectors were prohibitively expensive, consisted of a set of static images on a linear strip of 35mm film, typically derived from a longer moving-picture film and intended for projection with an accompanying lecture.Footnote 114 Danziger and Gloria Feliciano of the Mass Communication Institute of the University of the Philippines co-supervised a pair of graduate students who tailored the filmstrip to ‘barrios’ audiences by modifying the audio track, script, and scene order, and by aesthetically tweaking the hairstyle, fashion, village scenery, and so on. In practice, this involved projecting a scene from the original onto cardboard, colouring it in with magic marker, and photographing the revised scene. They further used the new images to produce flipcharts and posters (Figure 8).Footnote 115 While visiting the institute on a three-month training programme as a World Health Organization fellow, G. Kittu Rao likewise adapted the filmstrip for villages in South India through a similar process; he further planned to produce a ‘version with actual photographs depicting the same idea as the cartoon visuals and then to find out the effectiveness of the two versions’.Footnote 116

Figure 8. Luzviminda Gutierrez, a graduate student from the Philippines and recipient of a grant at the Communication Institute in Hawaii, is pictured redrawing the Disney material, with examples of her handiwork: IEC Newsletter 6 (May 1972), 4; with permission by the East–West Center.

This two-version possibility of the filmstrip further emphasizes the unfixed and unfinished status of Family Planning, existing as it did in some two dozen languages, multiple media formats, not to mention untraceable adaptations and experiments around the globe. As such, Family Planning was implementing earlier lessons learned in using film for public health goals. Kirsten Ostherr, again, has historically analysed a Rockefeller-funded film from 1920, Unhooking the Hookworm, which obliged the foundation to conclude that the film could only be an ‘effective educational tool’ if they were ‘to produce a virtually infinite number of versions of the film, each adapted to particular local circumstances’.Footnote 117 Following this logic, Family Planning, the film and media package, was to be adapted, tailored, and contested, well into its official release.

Legacy: a film in flux

Eventually, these debates concluded for a pragmatic reason – money ceased to flow. In April 1969, the Population Council stopped subsidising new prints of Family Planning.Footnote 118 The many extant prints continued to circulate, and be tailored, as described above, into the 1970s. In this regard, Family Planning bears instructive comparison with the science fiction film Soylent Green (1973), which also started out with a script that referred explicitly to forms of birth control. As we show elsewhere, MGM suppressed these references until the overpopulation ‘message’ of the original source material, the novel Make Room! Make Room!, was diluted to the point of unrecognizability.Footnote 119 Today, the film is best remembered not as an appeal for population control but as an eco-disaster movie about climate change. Drawing attention to contraception would have risked not only offending some religious organizations but also undermining the iconic cannibalistic conceit of the film. Nevertheless, dilution seems to be a pattern regarding the handling of contraception when major studios such as Disney or MGM are involved. Although the version of Family Planning which most viewers today encounter on YouTube significantly diverged from the initial scripts and storyboards, the evidence of tensions between Disney and the PC that we have located are not apparent in the ‘final’ product.

The film’s impact is harder still to reconstruct. While some deemed it a success, in this article we have presented evidence of a rather mixed reception and legacy.Footnote 120 As we have seen, some Latin American viewers resented being shown what they perceived as the Indian version of the film, disliked the title, were not convinced by the everyman character, and offered a critique of the film’s misogyny. In Pakistan, where a lightly edited version of the film was reportedly well received by Lahore television audiences, a Karachi doctor complained that the filmstrip fell completely flat with expectant mothers attending an antenatal clinic. In the Philippines and even within India, the filmstrip was further adapted for local relatability.

The almost inevitable failure of Family Planning to live up to expectations or provide a commensurate return on investment may have helped to usher in a new era of public health film. Public criticism was muted but, on closer inspection, the film seems to have facilitated a more sceptical view of the universal appeal and relatability of animated shorts. As Manon Parry has noted, NGOs moved away from the expensive and possibly distracting or ineffective medium of film, and communications experts began to experiment with alternatives, including ‘folk media’ such as songs, dance, storytelling, and puppet shows.Footnote 121 Eventually the cheapness of video allowed messaging to be tailored far more specifically than film or television ever had.Footnote 122 To say the least, Family Planning was not the start of a new trend. It was, rather, a contingent and unstable product of highly specific and short-lived conditions of possibility.

More than merely adding detail or texture, the archival records provide evidence of condescension within the PC (‘we live in the future – they live in the present only’) and anti-communism within the Disney corporation (‘keeping the number of communists in the world down to the lowest possible level’). No less crucially and perhaps more suggestively, it also evidences that critiques of the film as racist and sexist did not only become apparent to scholars in the Global North with the benefit of hindsight but were clearly articulated at the time by commentators in the Global South. Simply viewing the film, then, is not enough. To do so risks replicating the infantilizing, universalizing gaze of the PC, which seemed to view the Global South as a ‘kind of undifferentiated mass of high fertility’, in apparent ignorance of the culturally diverse audiences its leadership aspired to reach.Footnote 123 The uneven reception of Family Planning, spanning confusion to sophisticated critique, is a reminder that high production value and global distribution do not guarantee success.

Traces of the various further iterations of the film hint at a larger and for the most part hidden story about the transformative process of circulation and appropriation; the temporality of an unstable media object that might appear to casual viewers as static comes into focus. Feminist media scholars have recently diagnosed ‘incompletion’ as a ‘general condition of all film’.Footnote 124 There is never a final reading or understanding, certainly, but the ‘exhibition’ stage also changes over time. While prints of Family Planning have long been stored in libraries and archives, Disney has never rereleased the film. (It has, by contrast, restored and rereleased other ‘useful’ movies, such as its wartime propaganda films).Footnote 125 But the film has been shown in scholarly and repertory screenings, and is now (without Disney’s approval) streaming. It is quite possible that more people have seen Family Planning on YouTube than projected in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 126 Family Planning remains in flux.

Our analysis contributes to an approach to mass media and communication within the history of population control, and global history more generally. As we have seen, the combined might of Rockefeller and Disney failed to harness the alleged universal appeal of animation. Despite the massive investment, including in translational work, communicating overpopulation and family planning to specific local audiences around the world proved a hurdle that not even Donald Duck or the everyman character could overcome. In contrast to the generally assumed success of the film, examining the paper trail, as we have done, reveals a more tempered history. Digitization and streaming have made the audio-visual products of postwar international media campaigns, and much else besides, more accessible than ever. This has created new opportunities, but also new challenges.Footnote 127 In the absence of archival records, it is easy to project the same old stories, for instance, about US cultural hegemony, onto conveniently digitized but also radically de-contextualized films. To embed film and other media more fully in global histories, it is vital to search beyond the screen and attempt to follow production, circulation, and reception. Only then will hidden tensions, negotiations, contestations, and appropriations come into view, and with them a subtler and more nuanced history of, for example, international media campaigns in a period of unprecedented optimism about the universal language of film and, especially, animation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kim Alexander, Nick Hopwood, Bibia Pavard, three anonymous reviewers, and the Reproduction Virtual Circle for their careful readings of and incisive comments on earlier drafts; Michele Hiltzik Beckerman and Brent Phillips (RAC), Joseph Donnelly (USAID), Angela Saward (Wellcome Collection), and Phyllis Tabusa (EWC) for invaluable archival support; and Annika Berg (Stockholm University), Nicole Bourbonnais (IHEID), and Carol Tsang (HKU) for generously sharing their research with us.

Financial support

The authors received a Rockefeller Archive Center Research Stipend.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Patrick Ellis is Assistant Professor of Communication at the University of Tampa. He is a historian of film and media, and the author of Aeroscopics: Media of the Bird’s-Eye View (University of California Press, 2021). He has otherwise published in, e.g., The British Journal for the History of Science, Early Popular Visual Culture, Film History, Imago Mundi, and The Journal of Cinema and Media Studies.

Jesse Olszynko-Gryn is head of the Laboratory for Oral History and Experimental Media at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, Germany. He is the author of the book, A Woman’s Right to Know: Pregnancy Testing in Twentieth-Century Britain (MIT Press, 2023), as well as articles and chapters, including with Patrick Ellis, on the cinema of population control, feminist health activism, and the global circulation of reproductive technologies.