Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) exacerbated respiratory disease, also referred to as Samter's triad or aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, is a chronic, eosinophilic, inflammatory disorder of the respiratory tract occurring in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, asthma and hypersensitivity to cyclooxygenase-1 inhibiting drugs. It is estimated that up to 40 per cent of asthmatic patients with nasal polyposis potentially have NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease.Reference Jenkins, Costello and Hodge1 Despite some progress in the understanding of its pathophysiology, it remains a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.Reference Kowalski, Agache, Bavbek, Bakirtas, Blanca and Bochenek2 Diagnosis is mainly based on patient history, and aspirin provocation tests are only needed when the history is not clear.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Hopkins, Hellings, Kern and Reitsma3

Patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease typically have more extensive sinonasal disease when compared with patients without NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease, and their polyps are more recalcitrant to both medical and surgical treatments.Reference Amar, Frenkiel and Sobol4–Reference Young, Frenkiel, Tewfik and Mouadeb6 Current medical treatment of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease does not differ significantly from that of other chronic rhinosinusitis patients with nasal polyps and mainly consists of nasal corticosteroids, preferably in drop form, and nasal douches. Additional options include leukotriene receptor antagonists,Reference Ragab, Lund and Scadding7 the use of aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation, longer (tapering) treatment with oral corticosteroids, and long-term antibiotic and/or biological treatments when indicated.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Hopkins, Hellings, Kern and Reitsma3

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is key in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease and is primarily aimed at reducing tissue load and optimising local medical treatment. However, recurrence of nasal polyps after surgery is more frequent in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease than in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps without NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease.Reference Kowalski, Agache, Bavbek, Bakirtas, Blanca and Bochenek2,Reference Stevens, Peters, Hirsch, Nordberg, Schwartz and Mercer8 Failure rates of standard FESS in these patients are reported to be as high as 90 per cent at 5 years, and rates of revision surgery range from 38 to 89 per cent at 10 years.Reference Amar, Frenkiel and Sobol4,Reference Mendelsohn, Jeremic, Wright and Rotenberg9 Furthermore, patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease undergo twice as many sinus surgical procedures over the course of their disease, and they are usually younger at the time of their first surgery.Reference Shih, Patel, Choby, Nakayama and Hwang10

Guidelines have not been published on how best to manage recalcitrant nasal polyps in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease. It has been reported that patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease receiving more extensive FESS do better than those undergoing more conservative sinus surgery, with a reduction in disease recurrence, a reduced need for revision surgery and improved quality of life (QoL) scores.Reference Shih, Patel, Choby, Nakayama and Hwang10–Reference Adappa, Ranasinghe, Trope, Brooks, Glicksman and Parasher13 However, there is no consensus among surgeons on the optimal FESS extension (i.e. limited FESS vs large cavity FESS with or without Draf IIa, IIb or III) in order to reduce the risk of polyp recurrence to a minimum. Similarly, there is still debate over which are the best medical treatments to adopt post-operatively.

We present our case series of 13 patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease who were successfully treated with large cavity FESS and maximal post-operative medical therapy. Based on the latest evidence available and on our personal experience, we aim to suggest a flow chart to adopt in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease presenting with difficult-to-treat chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of patients undergoing large cavity FESS (i.e. complete uncinectomy, wide middle meatal antrostomy, complete ethmoidectomy, wide sphenoidotomy and Draf IIb or III) for NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease from January 2016 to March 2022 at the Royal National ENT Hospital (London, UK) was performed.

All patients were seen by a multidisciplinary team composed of a rhinology or allergy specialist and an ENT surgeon. The diagnosis of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease was confirmed by the presence of a diagnosis of asthma according to Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines,Reference Kroegel14 the observed presence of nasal polyposis and a history of aspirin intolerance with a typical reaction to cyclooxygenase-1 medications.Reference Miller, Mirakian, Gane, Larco, Sannah and Darby15

Population data including age, sex, co-morbidities, home medications, interval between diagnosis of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease and large cavity FESS, interval between first visit at our hospital and large cavity FESS, and interval between previous FESS and length of follow up were collected. In addition, pre- and post-operative number of FESS, endoscopic polyp grade, Lund–Mackay score and nasal symptoms were recorded.

Before considering surgical management, each patient had unsuccessfully undertaken a minimum three-month trial of maximal medical treatment, including intra-nasal topical corticosteroids, nasal douches with normal saline, a short course of oral steroids, a trial with Montelukast and a course of long-term oral antibiotics.

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1996 Helsinki Declaration and approved by the research ethic committee (reference: 06/Q0301/6). All investigations and treatments were carried out in line with accepted clinical practice. Quantitative variables were summarised using median and interquartile range (25–75), whereas qualitative variables were described using frequency and percentage.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent large cavity FESS under general anaesthesia with image guidance assistance. This surgery entailed a combination of a complete uncinectomy, wide middle meatal antrostomy, complete ethmoidectomy, wide bilateral sphenoidotomy, and a Draf IIb or III frontal sinus surgery. Draf III was performed by joining the Draf IIb bilaterally, thus removing the frontal sinus floor anterior to the olfactory cleft and the intersinus septum. The middle turbinate was resected very gently from an anterior to posterior direction, along its origin at the skull base. A diamond burr drill was used to reduce the frontal beak and the frontal intersinus septum or septa, if more than one was present.Reference Noller, Fischer, Gudis and Riley16 Finally, the nose was packed with absorbable packs soaked in betamethasone 0.1 per cent drops to reduce scarring and post-operative oedema.

Results

Population

Thirteen consecutive patients (six female and seven male) undergoing large cavity FESS for NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease with a median age of 47 years were included. All patients had a known diagnosis of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease and were referred to our tertiary referral centre for further management. Nine patients complained mainly of nasal blockage, four of sinus headache, five of post-nasal drip and two of anterior nasal discharge. All but one patient had an absent sense of smell. All patients had undergone previous FESS for their chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which failed to obtain optimal control of the disease. They were all under medical treatment with nasal steroids and douching for their chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and on regular inhalers for asthma treatment. Three patients had allergic rhinitis and were on oral antihistamines, and seven patients had benefitted from Montelukast and were continuing to take it daily. Clinical and demographic data are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

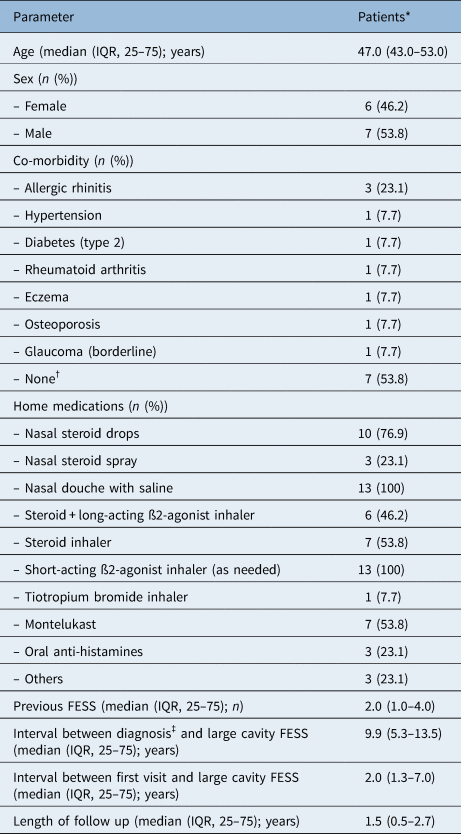

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data

*n = 13; †Please note that all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) exacerbated respiratory disease patients have asthma by definition; ‡first diagnosis of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease obtained from general practitioner records. IQR = interquartile range; FESS = functional endoscopic sinus surgery

Table 2. Pre-operative and post-operative sinonasal symptoms and measurements

*n = 13; †n = 13; ‡Post-operative symptoms and outcomes based on the latest available follow up; §interval between previous endoscopic sinus surgical procedures before undergoing large cavity functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS)

Pre-operative assessment

All patients received a pre-operative assessment, which consisted of an endoscopic evaluation and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the sinuses. Nasal polyps were graded endoscopically according to the Meltzer Clinical Scoring System (0 = no polyps, 1 = polyps confined to the middle meatus, 2 = multiple polyps occupying the middle meatus, 3 = polyps extending beyond middle meatus, 4 = polyps completely obstructing the nasal cavity),Reference Meltzer, Hamilos, Hadley, Lanza, Marple and Nicklas17 and radiological staging of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps was obtained by calculating the Lund–Mackay score.Reference Lund and Mackay18 Median polyp grade was 3, and the median Lund–Mackay score was 21, demonstrating an advanced stage of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (Table 2).

Post-operative course

There were no acute complications. Histology of the specimens showed allergic-type inflammatory polyps in three cases and inflammatory polyps only in the remaining cases. Post-operatively, all patients received a long-term macrolide treatment (clarithromycin 500 mg twice a day for 2 weeks, then clarithromycin 250 mg daily for 10 weeks) and a short course of oral corticosteroid (prednisolone 40 mg daily for 5 days), if not contraindicated. They were asked to douche their nose with normal saline at least twice a day followed by application of intranasal steroid drops (betamethasone sodium phosphate 0.1 per cent, two drops per nostril twice a day) in the ‘Kaiteki’ position for the first two weeks. On the third week, endoscopic debridement was performed in out-patients under local anaesthesia to clear crusts and debris. Patients were asked to continue with douching and commence fluticasone propionate nasal drops (400 μg divided between the nostrils) long term.

Follow up and post-operative outcomes

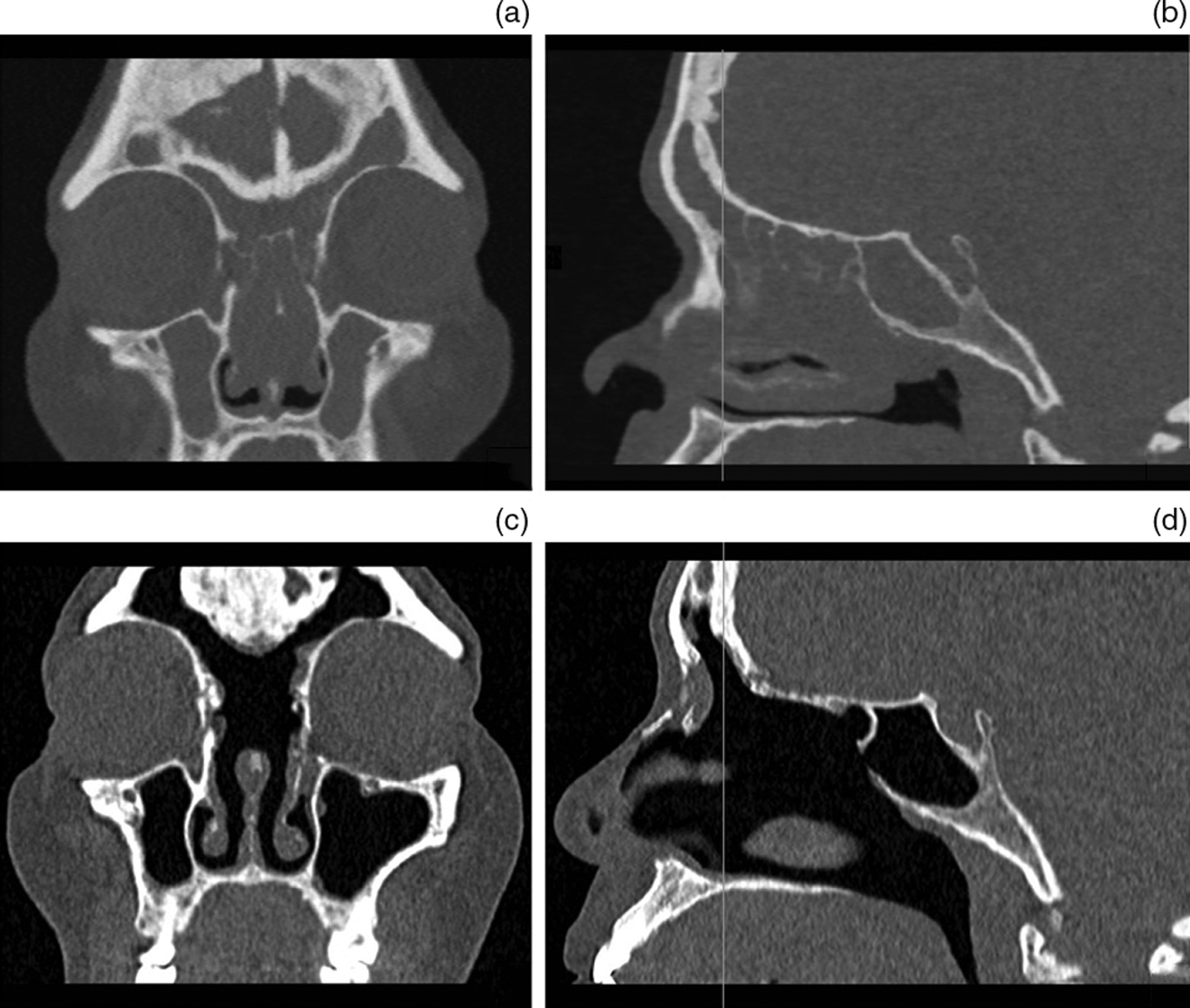

All patients were followed up with nasendoscopy in an out-patient setting. The median length of the follow up was 1.5 years, ranging from a minimum of 3 months to a maximum of 66 months (5.5 years). Two patients were lost at follow up and did not complete the minimum length of follow-up period of one year as per our current practice. An interval CT scan of the sinuses was also arranged on average one year after the operation for those completing the minimum follow-up period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pre-operative (a) coronal and (b) sagittal and post-operative (c) coronal and (d) sagittal computed tomography scans of a 60-year-old woman with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug exacerbated respiratory disease who underwent large cavity functional endoscopic sinus surgery for uncontrolled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.

In all cases, post-operative endoscopic evaluation showed well-controlled disease with a median polyp grade of 0 and a median Lund–Mackay score of 4 (Table 2). The operation was successful in all patients (100 per cent), and none of them needed a revision surgery. Most of the patients reported an improvement in their symptoms post-operatively. Sense of smell was still preserved in the patient who underwent Draf IIb, and it improved in four patients who underwent Draf III (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pre-operative and post-operative sinonasal symptoms and measurements. FESS = functional endoscopic sinus surgery

Discussion

Despite advances in medical and surgical therapy, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease remains a difficult disease to manage. The role of large cavity FESS in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease is still debated, and the extent of surgery used is highly variable among surgeons.

Draf III (or endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure) is widely accepted as the procedure of choice for recalcitrant frontal sinusitis, lateral frontal mucoceles, skull base tumours, trauma and cerebrospinal fluid leaks,Reference Chen, Wormald, Payne, Gross and Gross19,Reference Orlandi, Kingdom, Smith, Bleier, DeConde and Luong20 even though NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease has not been classically considered an indication. However, since its first description in the 1990s,Reference Draf21 indications have expanded and broadened, due in part to advancements in frontal sinus instrumentation and also to increased experience of the surgeons. In a recent meta-analysis, Shih et al.Reference Shih, Patel, Choby, Nakayama and Hwang10 observed a reduced incidence of re-operation and increased symptom improvement in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease receiving Draf III. Similarly, Naidoo et al.Reference Naidoo, Bassiouni, Keen and Wormald22 reported a reduction of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps recurrence rates in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease undergoing Draf III. Morrissey et al.Reference Morrissey, Bassiouni, Psaltis, Naidoo and Wormald11 suggested complete sphenoethmoidectomy, maxillary antrostomy and Draf IIa frontal sinusotomy as the initial surgical treatment for these patients, while reserving Draf III for those who failed that treatment in addition to three months of maximal medical treatment. In line with other authors, they reported a reduction of polyp recurrence to 60 per cent and need for revision surgery to 22.5 per cent.Reference Morrissey, Bassiouni, Psaltis, Naidoo and Wormald11

In this regard, our results support the efficacy of large cavity FESS in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease; in our case series, it halted the long-term progression of the disease, with no patients requiring further surgery at a median follow-up period of 1.5 years. The reasoning behind this is predicated on complete removal of all inflammatory burden within patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease through more extensive surgical removal.Reference Bassiouni, Naidoo and Wormald23 In fact, more radical surgery allows the eradication of inflammatory mediators (eosinophils in mucosa, eosinophil mucus, fungal and staphylococcal antigens, bacterial load, osteitic bony lamellae), thus contributing to the reduction of the local inflammatory load.Reference Bassiouni, Naidoo and Wormald23 In particular, we hypothesised that the two key areas that harbour residual disease load and cause early recurrence are the sphenoid and frontal sinus ostia regions. Therefore, a crucial step is to achieve a wide opening to all the sinuses, especially these two key areas. The aim is to ensure that all disease is removed with the creation of large sinus cavity openings. Currently, we suggest large cavity FESS, which includes Draf III, to all patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease with no sense of smell who have failed maximal medical treatment and/or conservative FESS and reserving Draf IIb for those with a residual sense of smell who are keen to preserve it. This is linked to the potential risk of Draf III to affect olfactory function. Additionally, blood tests to exclude eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis or an allergic fungal sinusitis, along with a CT scan of the sinuses should be arranged in cases of refractory chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Flow-chart showing the suggested surgical and post-operative management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug exacerbated respiratory disease (N-ERD) patients. CT = computed tomography; ATAD = aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation. *Additional medical treatments include: leukotriene receptor antagonists, aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation, longer (tapering) treatment with oral corticosteroids and long-term antibiotics. †Blood tests suggested: full blood count and differential, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, aspergillus antibodies, vitamin D levels, erythrocytes sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein.

Unfortunately, even after extensive sinus surgery, polyps can still recur. To further minimise the chance of recurrence of nasal polyps, a very important step is to ensure patients receive the maximal medical treatment also in the post-operative period. Recommended post-operative treatments after FESS include topical and systemic corticosteroids as well as long-term antibiotics.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Hopkins, Hellings, Kern and Reitsma3 However, a lack of evidence exists on the best post-operative approach to adopt specifically in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease. Rotenberg et al.Reference Rotenberg, Zhang, Arra and Payton24 in a double-blinded, randomised, controlled trial compared three different methods of medical therapy following FESS in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease. Interestingly, they found no clinical difference in terms of QoL and CT scan results at one year regardless of the post-operative irrigation used (either saline only, saline and nasal spray, or saline mixed with steroid).Reference Rotenberg, Zhang, Arra and Payton24 The best delivery mechanism of nasal steroid after sinonasal surgery is still debated because spray molecules may not land properly on the target of diseased mucosa.Reference Morrissey, Bassiouni, Psaltis, Naidoo and Wormald11 The use of steroid drops administered in the ‘Kaiteki’ position may help delivery of the steroid molecules to the new sinonasal cavities and in particular to the frontal sinuses and olfactory clefts, which could contribute to olfactory improvement by directly targeting the olfactory neuroepithelium.Reference Mori, Merkonidis, Cuevas, Gudziol, Matsuwaki and Hummel25 Despite a potential risk of smell impairment following Draf III, in our case series, 4 patients (30.8 per cent) reported an improvement in their sense of smell (Table 2, Figure 2), thus corroborating previous findingsReference Yip, Seiberlin and Wormald26,Reference Ninan, Goldrich, Liu, Kidwai, McKee and Williams27 that suggest a positive effect of Draf III on subjective sense of smell.

The role of aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation as an additional treatment to control polyp recurrence in post-operative care after large cavity FESS is not completely clear. Effectiveness of aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease has been demonstrated,Reference Swierczynska-Krepa, Sanak, Bochenek, Stręk, Ćmiel and Gielicz28–Reference Pendolino, Scadding, Scarpa and Andrews31 and its use has been shown to be both safe and clinically efficacious in improving QoL and total nasal symptom score.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Hopkins, Hellings, Kern and Reitsma3,Reference Pendolino, Scadding, Scarpa and Andrews31,Reference Woessner and White32 However, what is emerging is that continuing aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation in the post-operative period may help to stabilise the surgical results by reducing polyp recurrence. Several studies,Reference Adappa, Ranasinghe, Trope, Brooks, Glicksman and Parasher13,Reference Havel, Ertl, Braunschweig, Markmann, Leunig and Gamarra33–Reference Cho, Soudry, Psaltis, Nadeau, McGhee and Nayak35 in fact, demonstrate that patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease undergoing FESS and receiving post-operative aspirin desensitisation show a significant improvement in QoL, a reduction in chronic rhinosinusitis-related symptoms and a trend toward reduced nasal polyp relapse.

• Patients with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) exacerbated respiratory disease typically have more extensive sinonasal disease when compared to patients without

• A reduction in disease recurrence and need for revision surgery have been reported in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease patients receiving more extensive functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS)

• This study included 13 NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease patients with recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

• There was a reduction in Lund–Mackay score and an improvement in the nasal symptoms with no patients requiring further surgery at a median follow-up period of 1.5 years

• Large cavity FESS with optimal post-operative treatment is effective in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease and seems to halt chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps progression

Biological treatments are emerging as a valuable alternative in the treatment of NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease by showing promising results in the control of nasal polyp growth. So far, the only monoclonal antibody that has been approved for the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is Dupilumab (anti-interleukin-4 receptor α), but its effectiveness in the long term is still under trial evaluation.Reference Fokkens, Lund, Hopkins, Hellings, Kern and Reitsma3 Nevertheless, the cost for a biological treatment per person per year is still too high for it to be used as a routine treatment.

In our practice, we suggest a long course of macrolide to all patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease who undergo Draf III, if there are no contraindications, along with daily long-term nasal steroid drops and nasal douches with normal saline. Whenever possible, post-operative aspirin treatment after aspirin desensitisation (either oral or intranasal) should be suggested to patients showing an early recurrence of nasal polyps. In patients failing this treatment, biological treatments can be considered as an option, whereas revision surgery (i.e. polypectomy) should be offered as a last resource in the case of uncontrolled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (Figure 3).

Finally, we noted a lack of agreement on the nomenclature. Over the years, authors have been using different terms (‘radical’, ‘extensive’ or ‘full-house sinus surgery’) to refer to the same type of surgery, with the result of creating confusion among readers. In our opinion, the term ‘large cavity’ better describes this type of sinus surgery, which aims to establish a wide communication among all the sinuses, thus creating a large nasal cavity. Therefore, the term ‘large cavity FESS’ should be used when wide antrostomy, complete ethmoidectomy, or wide sphenoidotomy combined with a Draf IIb or III are performed.

Conclusion

Management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease still remains challenging. Large cavity FESS appears to be an effective treatment by halting the progression of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and should be suggested as a primary procedure in this high-risk category of patients. We highlighted the importance of achieving a wide opening of all the sinuses, especially the frontal and sphenoid sinuses, which represent the commonest sites for residual polyp disease. Post-operative care is extremely important in patients with NSAID-exacerbated respiratory disease undergoing sinonasal surgery, and in order to prevent polyp recurrence, an optimal post-operative treatment should be established.

Competing interests

None declared