Introduction

Balance disorders are common in the USA, with an estimated lifetime incidence of up to 40 per cent.1,Reference Murdin and Schilder2 Vertigo, dizziness and postural instability in chronically affected adults significantly reduces quality of life and increases the risk of falls, the sequelae of which include fracture, hospitalisation and death.Reference Carpenter, Cameron, Ganz and Liu3,Reference Dougherty, Carney and Emmady4 The aetiology of vestibular loss can include any combination of infection, aging, head trauma, benign positional paroxysmal vertigo or exposure to ototoxic medications.Reference Kleffelgaard, Soberg, Tamber, Bruusgaard, Pripp and Sandhaug5,Reference Han, Song and Kim6 Should the underlying cause of imbalance be fluctuating or spontaneous with prolonged labyrinthine pathology, as in the case of Ménière's Disease, pharmacological and surgical intervention may be warranted. When the aetiology of imbalance is stable, vestibular rehabilitation therapy becomes the ‘gold standard’ for an effective exercise-based means to manage chronic balance dysfunction.Reference Hall and Cox7

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy exercises are designed to facilitate adaptation and compensation of the vestibular system to previously lost function.Reference Burzynski, Sulway and Rutka8 Primary objectives include vertigo or dizziness reduction, improvement in postural stability, enhancement of gaze stability, and resumption of baseline activities of daily living.Reference Hall and Cox7 Although effective, progression in vestibular rehabilitation therapy may be inhibited by non-adherence to the prescribed regimen, as well as behavioural and psychiatric barriers.Reference Huang, Feng, Li and Lv9 Adjunct therapies may therefore, in theory, play a role in the management of postural instability where progress through traditional vestibular rehabilitation therapy has plateaued.

Previous studies exploring balance dysfunction treatments have considered the efficacy of tai chi chuan (tai chi), a centuries-old Chinese conditioning exercise derived from martial arts that emphasises full body control.Reference Lan, Lai and Chen10 Practitioners of tai chi use methodical, flowing movements in choreographed ‘forms’ to develop physical, emotional and spiritual well-being.Reference Yang, Wang, Ren, Zhang, Li and Zhu11 A body of literature encompassing the previous three decades has noted the efficacy of tai chi for primary prevention of chronic disease and the improvement of insomnia, pain reduction, flexibility and self-esteem. In addition, tai chi has been effective in health promotion for patients with cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinson's disease and osteoarthritis.Reference Siu, Yu, Tam, Chin, Yu and Chung12,Reference McGibbon, Krebs, Wolf, Wayne, Scarborough and Parker13

When considering balance, examples in the literature have reported overall balance control and proprioception recovery after standalone tai chi therapy.Reference Jiménez-Martín, Meléndez-Ortega, Albers and Schofield14,Reference Huang, Nicholson and Thomas15 However, the use of tai chi in the context of vestibular rehabilitation therapy has been seldom explored. Huang et al., in a systematic review, identified four studies to date that used tai chi tangentially to or instead of a prescribed course of vestibular rehabilitation, none of which explicitly reported plateauing or maximisation of therapeutic benefit.Reference Huang, Nicholson and Thomas15 To that end, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of a tai chi programme for adult patients with improved but persistent vestibular symptoms following completion of a traditionally prescribed course of vestibular rehabilitation therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients were recruited from a university-based comprehensive vestibular rehabilitation centre per recommendation by a physical therapist specialising in vestibular disorders. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adults aged 18 years or older, (2) patients with a definitive diagnosis of vestibular dysfunction, (3) patients who were naive to the practice of tai chi; (4) patients who had completed a course of vestibular rehabilitation therapy (minimum 16 sessions) within two months of enrolment, and (5) patients who were discharged secondary to a plateau in progress, with indications that they (6) had persistent vertigo and/or dizziness on discharge.

Patients were excluded if they: (1) could not communicate in English, (2) were physically unable to perform basic tai chi movements or (3) if they had a history of previous non-adherence to vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Patients were not explicitly excluded if immobility was secondary to pain. This prospective cohort study was approved by the institutional review board at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, number: 07-00032, and all patients gave informed consent.

Tai chi instruction

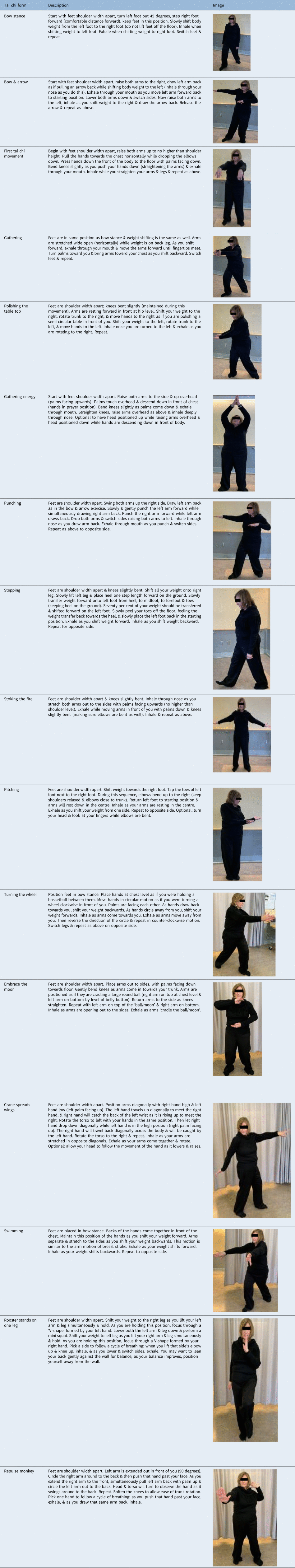

Tai chi sessions were held at the out-patient vestibular therapy clinic in cohorts with a minimum of 4 patients and maximum of 7 patients per group. Patients were seen in a class instructed by one of the vestibular therapists for a 45–60 minute period, once weekly for 8 weeks. Selected tai chi forms were derived from the Yang style, the most widely utilised form of tai chi, and were chosen to initially minimise head movement to reduce aggravation of vestibular symptoms and optimise weight shifting for postural stability. Each session taught and reinforced two new movements, which were progressively combined over the following sessions to yield a total of 16 cumulative forms upon programme completion. Pictorial tai chi forms with accompanying descriptors can be observed in Appendix 1. Participants were encouraged to practise all tai chi movements learned twice daily.

Measures of vestibular function

The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale, Dynamic Gait Index and Dizziness Handicap Inventory were used to assess balance outcomes, with testing undertaken immediately prior to the first tai chi session and directly following the last session. All patients completed the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and the Dynamic Gait Index, pre- and post-treatment.

The Dynamic Gait Index is a measurement of balance and fall risk in older adults and is composed of 8 balance-oriented tasks that are ordinally scored from 0–3. Individual item scores of 0 indicate severe gait impairment, and scores of 3 suggest normal gait function.Reference Shumway-Cook, Baldwin, Polissar and Gruber17 Combined Dynamic Gait Index scores of 19 or less out of 24 are predictive of increased fall risks in community-dwelling elderly adults and individuals with vestibular dysfunction.Reference Powell and Myers18 Pre- and post-intervention assessment of Dynamic Gait Index was completed by the same therapist.

Both the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and Dizziness Handicap Inventory are self-administered subjective matrices. The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale is a 16-item measurement of confidence in personal ability to perform routine balance-oriented functions scored as a percentage (0 per cent as lowest confidence and 100 per cent as highest confidence).Reference Myers, Fletcher, Myers and Sherk19 Final scores are calculated as an average percentage of all responses, with a threshold less than 50 per cent suggesting a low level of physical function and a threshold less than 67 per cent predicting future falls in older adults.Reference Lajoie and Gallagher20,Reference Zamyslowska-Szmytke, Politanski and Jozefowicz-Korczynska21 The Dizziness Handicap Inventory is a 25-item assessment of severity of debilitation from dizziness, with scores of 0, 2 and 4 points assigned to responses of no, sometimes and yes, respectively. Cumulative scores are derived from the summation of all items for a maximum of 100 points.Reference Graham, Staab, Lohse and McCaslin22 A higher Dizziness Handicap Inventory score indicates worsened perception of handicap from dizziness, and established score ranges of 0–30, 31–60 and 61–100 indicate mild, moderate and severe handicap, respectively.Reference Pu, Sun, Wang, Li, Yu and Yang23

Statistical analysis

Pre- and post-treatment measures of balance scores, score change and patient age were analysed as continuous variables. A Shapiro–Wilk test was used to ascertain normality of continuous variables, and changes in pre- and post-treatment Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale, Dynamic Gait Index and Dizziness Handicap Inventory were compared using a paired samples t-test for normally distributed data. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for non-parametric data. Data were recorded as mean and standard deviation. Score differences or change were calculated as raw post-test score minus raw pre-test score.

Patient age was analysed as a potential independent predictor of post-treatment balance outcomes (pre- and post-tai chi Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale, Dynamic Gait Index, Dizziness Handicap Inventory) using a Spearman's rho correlation. Post-tai chi subjective measures (Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and Dizziness Handicap Inventory) were correlated to the post-tai chi objective measure (Dynamic Gait Index) in an additional bivariate analysis using Spearman's rho.

Results

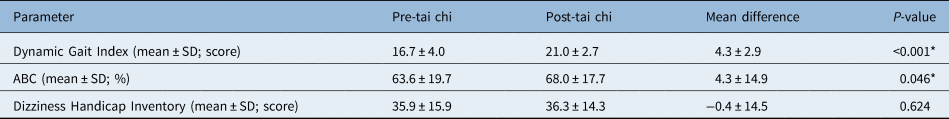

Fifty-one patients (47 female, 4 male) were enrolled in this study from April 2010 to December 2016, of which 37 participants completed pre- and post-intervention testing of vestibular outcome measures. The majority of participants were female (91.9 per cent; 34 female, 3 male). Demographic data are indicated in Table 1. Mean age among patients who completed treatment was 76.7 years (range, 56–91; standard deviation, 3.9 years). Three patients were unable to complete all 8 requisite sessions, and 11 were lost to follow up on post-treatment testing. Average Dynamic Gait Index, Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and Dizziness Handicap Inventory for patients with mean differences are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic data and balance assessment of tai chi participants

ABC = Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale

Table 2. Mean balance assessment matrices before and after tai chi programme

*Statistically significant values. SD = standard deviation; ABC = Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale

Among the 37 assessed patients, 36 (97.3 per cent) improved in one or more balance outcome measure. A total of 34 of 37 (91.9 per cent) showed improved gait on the Dynamic Gait Index, 24 of 37 (64.9 per cent) increased in confidence for balance-related tasks on the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and 7 of 18 (38.9 per cent) showed improvement on the Dizziness Handicap Inventory.

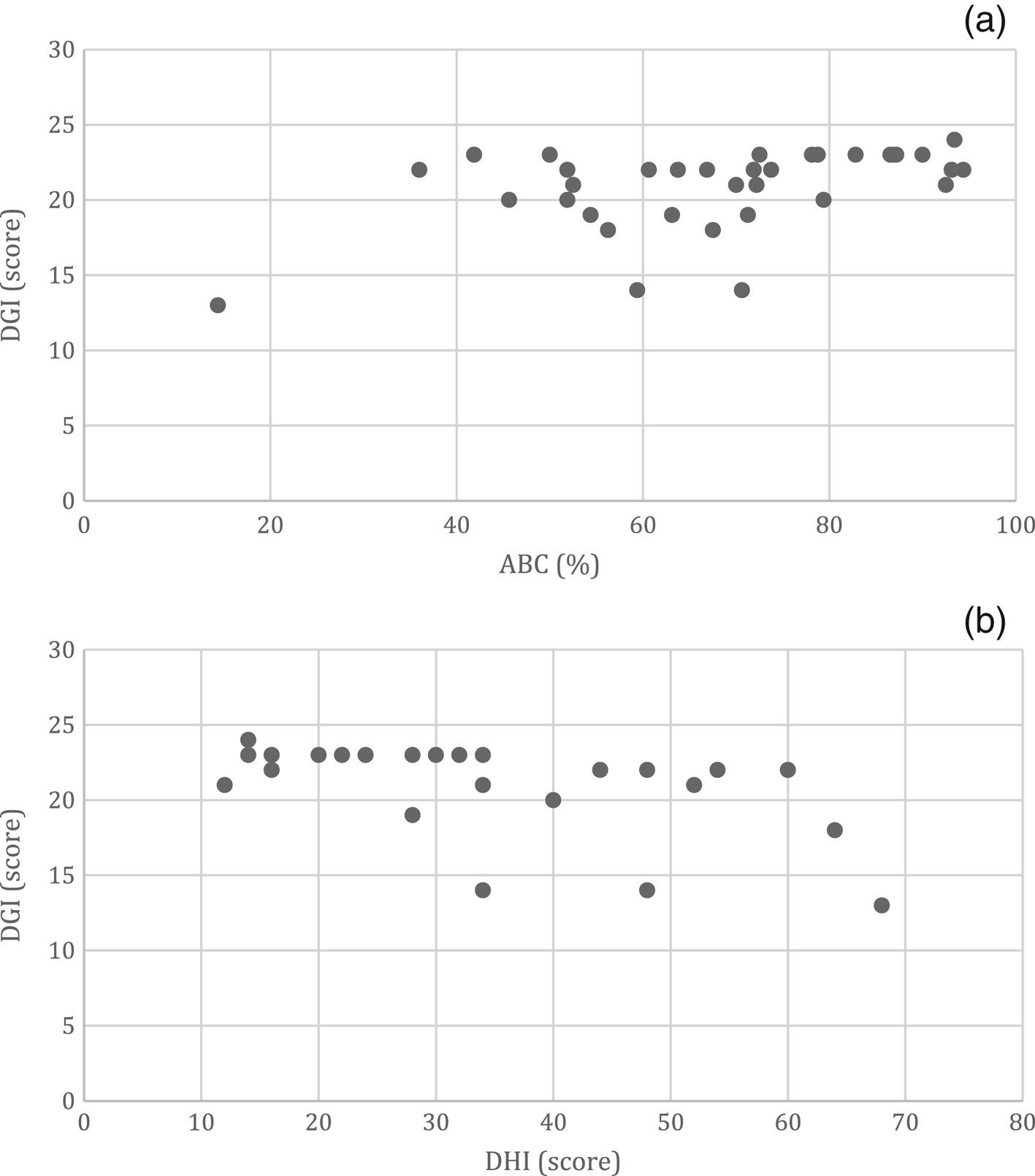

Mean Dynamic Gait Index and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale scores increased significantly upon completion of the tai chi programme (t = 8.88, 1.73; p < 0.00001, p = 0.0458; paired samples t-test) (Figure 1, Table 2). Mean Dizziness Handicap Inventory scores did not significantly change (z = −0.49, p = 0.62; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Age was not associated with score changes in Dynamic Gait Index or Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale (r s = 0.21, −0.15; p = 0.21, 0.36; Spearman's rho). However, age was negatively and moderately correlated to a change in Dizziness Handicap Inventory (r s = −0.57, p = 0.01; Spearman's rho). Post-tai chi Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale was moderately and positively correlated with post-tai chi Dynamic Gait Index, and post-tai chi Dynamic Gait Index was strongly and negatively correlated with post-tai chi Dizziness Handicap Inventory (r s = 0.48, −0.63, p = 0.002, 0.005; Spearman's rho) (Figure 2). Both aforementioned correlations indicated improved outcomes (lower Dizziness Handicap Inventory and higher Dynamic Gait Index and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale indicate better balance).

Fig. 1. Change in mean (a) Dynamic Gait Index and (b) mean Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale before and after tai chi therapy (p < 0.001, p = 0.046, paired t-test, respectively). Designated threshold for fall risk is indicated for each respective assessment of balance. A Dynamic Gait Index at or below 19 and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale below 67 per cent indicate the patient is at a higher risk of falls.

Fig. 2. Spearman correlation between subjective and objective measurement of balance for (a) Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale versus Dynamic Gait Index (DGI) and for (b) Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) versus Dynamic Gait Index (r s= 0.48, −0.63; p = 0.002, p = 0.005, Spearman's rho, respectively). Higher Activities–Specific Balance Confidence scale and lower Dizziness Handicap Inventory scores suggest greater subjective balance.

Discussion

Tai chi has demonstrably ameliorated symptoms of imbalance in previous studies. Huang et al. identified four such trials spanning 2006–2012, all of which reported positive results in vestibulopathy using differing measures of balance.Reference Wrisley, Walker, Echternach and Strasnick16 No papers to date have explored the use of tai chi in continually symptomatic patients who plateau in vestibular rehabilitation therapy performance. Consequently, the addition of a novel prospective cohort to this limited body of literature affords the possibility for future adjustments to the management of contemporary vestibular rehabilitation therapy.

The results of this investigation suggest a modified tai chi programme can plausibly improve balance outcomes in individuals who fail to maximise benefit from vestibular rehabilitation therapy, with significant recovery in the Dynamic Gait Index and Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale in this cohort after tai chi therapy. It can be further suggested that functional ability and balance confidence are improved after completion of the tai chi programme. In addition to the vestibular, visuospatial and proprioceptive systems, general balance is controlled by an amalgamation of factors affecting static and dynamic balance, notably mental condition and confidence.Reference Ogihara, Kamo, Tanaka, Azami, Kato and Endo24 To that end, bivariate analysis of subjective balance measures found moderate to strong associations between perceived level of handicap or confidence in balance abilities (Dizziness Handicap Inventory or Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale) and improvement in practical performance in balance-related tasks (Dynamic Gait Index).

Participation in a low-stress, less physically demanding form of balance training such as tai chi likely facilitates the development of perceived self-efficacy that is observable on the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale and Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Perceived self-efficacy is defined by Albert Bandura as an individual's belief about their ability to produce certain levels of performance that in turn influence life-affecting events.Reference Bandura25 In the context of our findings, further improvement after plateaued vestibular rehabilitation therapy progress in this cohort may be attributed to group dynamics or a comparatively higher degree of engagement. Although vestibular rehabilitation therapy is typically individualised, it may not encourage the social interactions of tai chi group therapy, which is conducive to resilience in a prescriptive exercise regimen.

• Balance disorders are common, and accidental falls and their sequelae may result in severe morbidity

• Vestibular rehabilitation therapy is a well-recognised, effective exercise-based treatment for balance dysfunction

• Tai chi has been minimally explored as an adjunct to vestibular rehabilitation therapy

• Empirically, tai chi can improve balance in patients who no longer attain benefit from traditional vestibular rehabilitation

Of particular interest are the predictive thresholds for fall risk established by Shumway-Cook et al. for the Dynamic Gait Index (score of 19 or less) and Myers et al. for the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence scale (score of lower than 67 per cent).Reference Shumway-Cook, Baldwin, Polissar and Gruber17,Reference Myers, Fletcher, Myers and Sherk19 For both measures, pre-tai chi mean scores were initially below the threshold indicating a higher fall risk but significantly increased to surpass the aforementioned set points after the eighth tai chi session (Figure 1). Although it would be premature to conclude that performance of tai chi definitively reduces fall risk, subject participation in comparable programmes noted in the study by Huang et al. may have contributed towards adaptation, habituation, or substitution of sensorimotor and psychosocial factors of balance.Reference Hall and Cox7,Reference Huang, Nicholson and Thomas15 It is possible that any combination of these facets, or the development of improved self-efficacy, may be contributory to a reduced fall risk in this cohort.

This study had several limitations. Although 97.3 per cent of patients had at least one improved balance outcome measure, comparisons of the benefits from tai chi to a control group were limited by methodological constraints. Although the areas of improvement in vestibular rehabilitation therapy (improved postural reflexes, sensory organisation and gaze stability) have been widely documented, there is no data available to suggest spontaneous or continued recovery of dizziness, vertigo, daily function and behavioural confidence after discharge in the absence of further intervention.Reference Neuhauser, von Brevern, Radtke, Lezius, Feldmann and Ziese26 Therefore, although this cohort experienced significant improvement in balance measures, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to ascertain how longitudinal performance would have been affected in the absence of intervention.

Cohort distribution by underlying vestibular pathology further limited the generalisability of study findings because patients enrolled in this study had a diverse array of vestibular diagnoses. Symptomatology similarly varied among patients, including any combination of dizziness, vertigo and imbalance. Owing to existing limitations, the use of tai chi as an adjunct to, or as a facet of, vestibular rehabilitation therapy is worthy of further investigation.

Conclusion

Tai chi demonstrates promise as a post-rehabilitative adjuvant to further recover balance in patients with vestibular disorders who have completed a course of vestibular rehabilitation therapy. When compared with their post-vestibular rehabilitation therapy baseline, patients who completed a modified tai chi programme were likely to perform better on routine balance-oriented tasks and may become more confident in their postural abilities. Further investigation of tai chi as an adjunct after vestibular rehabilitation therapy may inform future means by which limits in therapeutic performance can be surpassed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Stanislaw Sobotka for his consultation in statistical analysis.

Competing interests

None declared

Appendix 1 Tai chi form