Healthcare providers and systems increasingly recognize the impact social needs have on health outcomes.Reference Beck, Cohen and Colvin1 Community-based social care providers and organizations similarly recognize the health impact their work has on their clients. This mutual recognition accompanies a proliferation of partnerships between health and social care systems, between clinicians and community-based organizations.Reference DeVoe, Bazemore and Cottrell2 Such partnerships take multiple forms and range from mutual awareness to sustained co-ownership of process and outcome.Reference Liu, Beck and Lindau3 Medical-Legal Partnerships (MLP) address health-harming legal needs experienced by low-income families.Reference Regenstein, Trott, Williamson and Theiss4 Some MLPs are based within hospitals, others within outpatient health centers and clinics, and still others in communities. Nearly 200 legal aid agencies and 60 law schools are the legal partner within MLPs, bringing critical legal expertise into clinical encounters.5

Our MLP, the Cincinnati Child Health-Law Partnership (Child HeLP), was created in 2008. Child HeLP is a joint initiative that bridges the primary care clinics at Cincinnati Children’s with the Legal Aid Society of Greater Cincinnati (LASGC).Reference Klein, Beck, Henize, Parrish, Fink and Kahn6 Medical and legal partners realized at program outset that there was an overlap between the patients (or, clients) served and the outcomes sought (health and well-being for children and families). The partnership was built atop these commonalities and was developed to both address health-harming legal needs and improve child health outcomes. Data suggest that our partnership is effective: we recently showed that Child HeLP referral was associated with a 38% reduction in hospitalizations.Reference Beck, Henize and Qiu7 Child HeLP has also enhanced our ability to monitor and respond to patterns — e.g., delayed public benefits for families with newborns and clusters of housing risks.Reference Beck, Klein, Schaffzin, Tallent, Gillam and Kahn8 MLPs like Child HeLP have the very real benefit of enabling such a move from patient to population health, client to population justice.Reference Tyler and Teitelbaum9

Managing an MLP that lasts, grows in size and impact, and consistently identifies opportunities for innovation, adaptation, and advocacy takes effort.Reference Henize, Beck, Klein, Adams and Kahn10 In this article, we highlight the steps, measures, and approaches we use for partnership co-management. We discuss our use of quality improvement (QI) methods and statistical process control (SPC) charts to optimize our partnership and facilitate identification of patterns amenable to population-level action and policy change.Reference Benneyan, Lloyd and Plsek11 Finally, we discuss how additional clinical-community partnerships have followed the Child HeLP model.Reference Hensley, Lungelow and Henize12

Child HeLP Intervention

Child HeLP’s medical partner is Cincinnati Children’s primary care, inclusive of three clinical sites which care for ~40,000 predominantly low-income children and adolescents. More than 90% of patients are publicly insured. Child HeLP’s legal partner is LASGC, a regional non-profit law firm serving low-income families in seven Southwest Ohio counties. LASGC attorneys or paralegals staff an office at the largest of the CCHMC primary care sites 4-5 days per week.

Figure 1 illustrates Child HeLP’s referral process. Social needs screening, now common in pediatric primary care, provides an opportunity to identify needs which may be amenable to legal remedy. When we first implemented Child HeLP, we added standardized questions and space to record answers into the Cincinnati Children’s electronic health record (EHR), questions that assessed access to public benefits, housing quality and security, educational needs, and more. Our medical, social work, and legal teams co-created screening questions of most relevance to the Child HeLP intervention when no existing tool could be found.Reference Beck, Klein and Kahn13 Medical and legal partners also co-developed curricula to increase the clinical team’s knowledge of social determinants of health, how to effectively identify risks and needs, and how to refer to both clinic- and community-based resources.

Figure 1 Referral process, connecting patients seen in pediatric primary care with legal advocates via a clinic-based medical-legal partnership

Abbreviations: MLP – medical-legal partnership

If a patient screens positive for a social need during the healthcare visit, the clinician can discuss resources and referrals with the family, including Child HeLP. For health-harming legal needs (e.g., public benefit denial/delay, threat of eviction), the provider places a Child HeLP referral “order” within the EHR. Before the referring provider, generally a physician or social worker, enters the order, the patient’s parent/guardian must consent to sharing of protected health information and legal case information by signing separate authorizations for both medical and legal partners. The referral order looks the same as similar orders used to refer to clinical subspecialists. This has normalized, and elevated the importance of, such referrals within our clinical settings. Use of the EHR has also made the workflow more seamless for clinicians and allowed us to pull data from the EHR for QI and research.

Initially, the referral was automatically routed from the EHR to a printer located in the Child HeLP office in our largest primary care center. Legal advocates collected referrals when onsite to meet with patients and consult with healthcare providers. In 2015, we revised this process to make it more efficient and mitigate the risk of delayed receipt resulting from printer malfunctions or legal partners working off site. We now route the EHR order to an email inbox, allowing for quicker contact between attorney or paralegal and family. This change proved particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic when legal aid staff were working remotely.

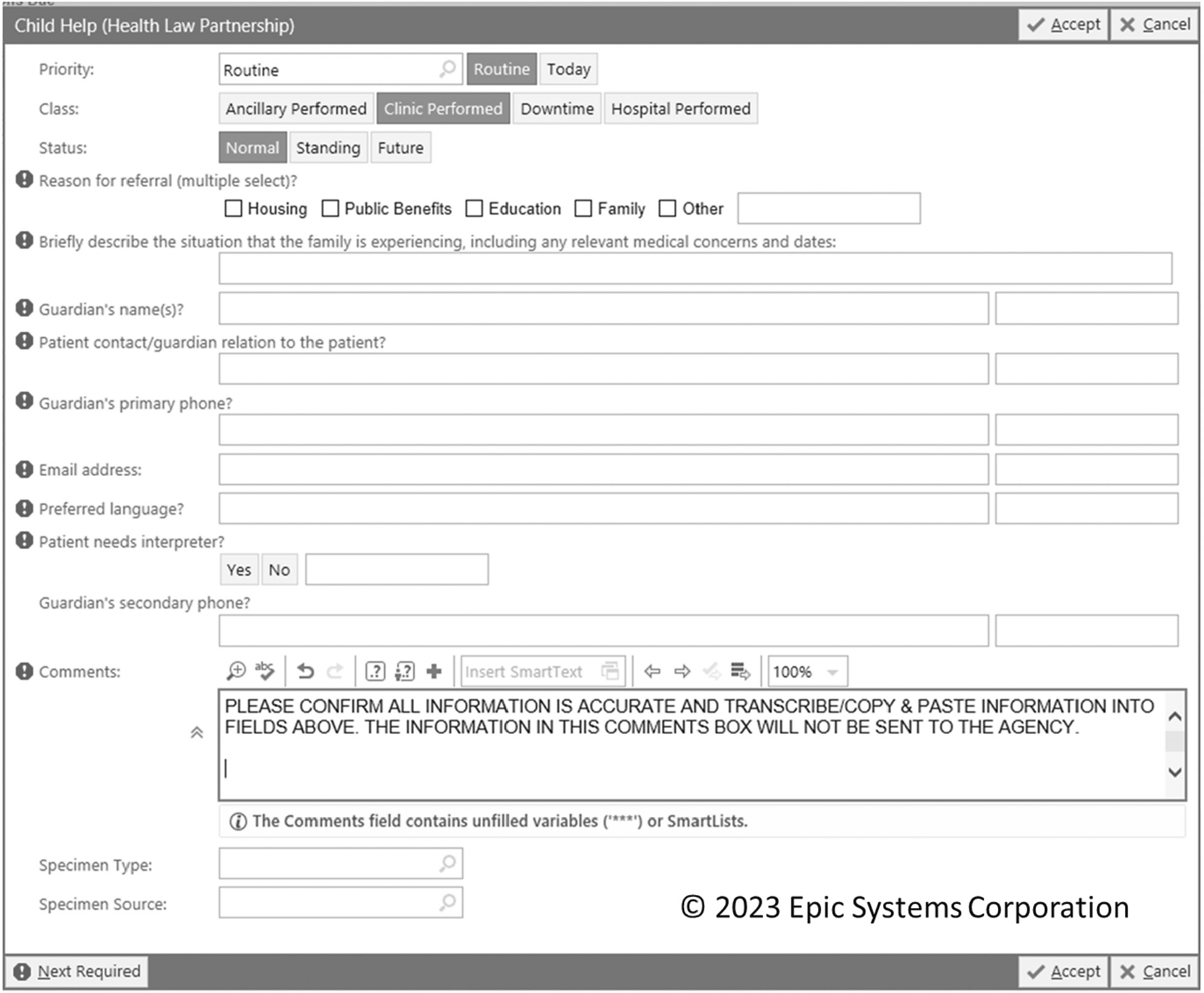

The initial EHR order fields, developed by the Epic Systems Corporation, asked providers to fill in text with the reason for referral and the parent/guardian’s name and phone number. In Fall 2022, we revised the EHR order to ease our ability to evaluate the program using data extractable from the EHR, better detail reasons for referral, provide more clinical context to legal partners, and enhance our ability to connect with families. The order now indicates reasons for referral (e.g., public benefits, housing), relevant medical concerns, and notation of whether the family needs an interpreter (Figure 2).

Since Child HeLP’s inception in 2008, medical partners have made 10,190 referrals to legal partners for 7,801 children. A single referral can affect multiple individuals within a family or household. Thus, we estimate these referrals have affected at least 18,442 children and 9,160 adults.

Figure 2 Screenshot of the order for the medical-legal partnership referral based in our electronic health record

Once LASGC receives the referral, the referring provider, shared patient identifier, case type, and legal need are entered into Pika, the electronic case management software used by LASGC. These data are entered by LASGC’s Health-Law Partnership Legal Services Coordinator. If intake was unable to be done by onsite LASGC staff, this intake specialist calls the family, generally within 24-48 hours to complete intake and facilitate assignment to a legal advocate with need-specific expertise. A Cincinnati Children’s program manager shares the prior week’s referral list from the EHR with the Legal Services Coordinator, who reconciles the list with referrals noted in Pika. Any “missing” referrals are realized and addressed. LASGC shares monthly referral reports from Pika which denote the status of the referrals. Legal partners also share reports with medical partners every six months, listing case outcomes by case type.

Co-Management of Child HeLP

Child HeLP launched following 18 months of strategic planning between Cincinnati Children’s and LASGC that culminated in the execution of a memorandum of understanding. Initially, an advisory council of leaders from Cincinnati Children’s and LASGC met regularly to guide and direct Child HeLP’s development and implementation. Once underway, the advisory council was replaced with a multidisciplinary management team. This team balances representation from both organizations and includes diverse functional representation, from executive sponsors to direct service representatives. Many members of this team have worked together on Child HeLP for over a decade, facilitating deep trust, mutual understanding of both organizations’ mission and processes, and a shared commitment to continual improvement and sustainability. The team meets monthly for an hour to track and discuss key functions and issues important to both medical and legal partners. The team discusses general updates, reviews data on key shared outcome and process measures, funding, capacity, and emerging opportunities (e.g., research studies, training/education opportunities, advocacy related to a public benefit or specific housing complex).

The team’s ability to manage the partnership is bolstered by data, captured from both Cincinnati Children’s and LASGC. We use these data for co-management and QI, tracking outcome measures like public benefits received, improved housing conditions, and educational needs met. We also track the number of referrals, the rate of referrals per well-child visits, referring clinician role (e.g., resident physician, attending physician, social worker, psychologist), and case types (health/income, housing, family, education, miscellaneous). Process measures assess steps in the referral pathway from need identification to resolution. For example, we measure fidelity to social (and legal) need screening, the rate at which referred families reach LASGC, the rate at which referrals result in open cases, and the rate at which open cases reach resolution. We also capture qualitative insights from cases, and we share case outcomes back to the clinical team who made the referral to illustrate impact.

Our approach to measurement has evolved since Child HeLP began roughly 15 years ago. Initially, we were reliant on anecdotes and simple descriptive statistics. True data sharing was ad hoc; legal aid had to offer information to the clinical team, or the clinical team had to explicitly ask for information. Early on, using a QI framework, we realized that capturing data over time held promise.14 As such, our simple tables were converted to run charts, visual representations of data over time. Run charts are governed by statistical rules that separate “common cause” variation (i.e., inherent to system in place, “noise”) from “special cause” variation (i.e., indicative of change in system) to enable rapid-cycle evaluation and action. To identify special cause variation more quickly, we transitioned to statistical process control (SPC) charts. SPC charts calculate “control limits” to differentiate “special cause” from “common cause” variation.15 Charts include annotations of background changes in our clinics or community and changes deployed to optimize the partnership (e.g., modifications to referral process). We track charts for all clinical sites, and for each clinical site, referring provider, and case type. We do so to learn from variability and support pattern recognition.

Patient-Level Measures Used for Quality Improvement

Since Child HeLP’s inception in 2008, medical partners have made 10,190 referrals to legal partners for 7,801 children. A single referral can affect multiple individuals within a family or household. Thus, we estimate these referrals have affected at least 18,442 children and 9,160 adults. The most common reasons for referral are housing instability/adverse housing quality (~40%), public benefit denials or delays (~25%), and unmet educational needs (~20%). Referrals have resulted in an estimated $1,360,000 in recovered benefits and improvements in housing conditions, educational achievement, and more. There were more referrals to Child HeLP in 2022 than any previous year (1,139 in 2022, compared to ~800 annually in years prior) likely driven by needs magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

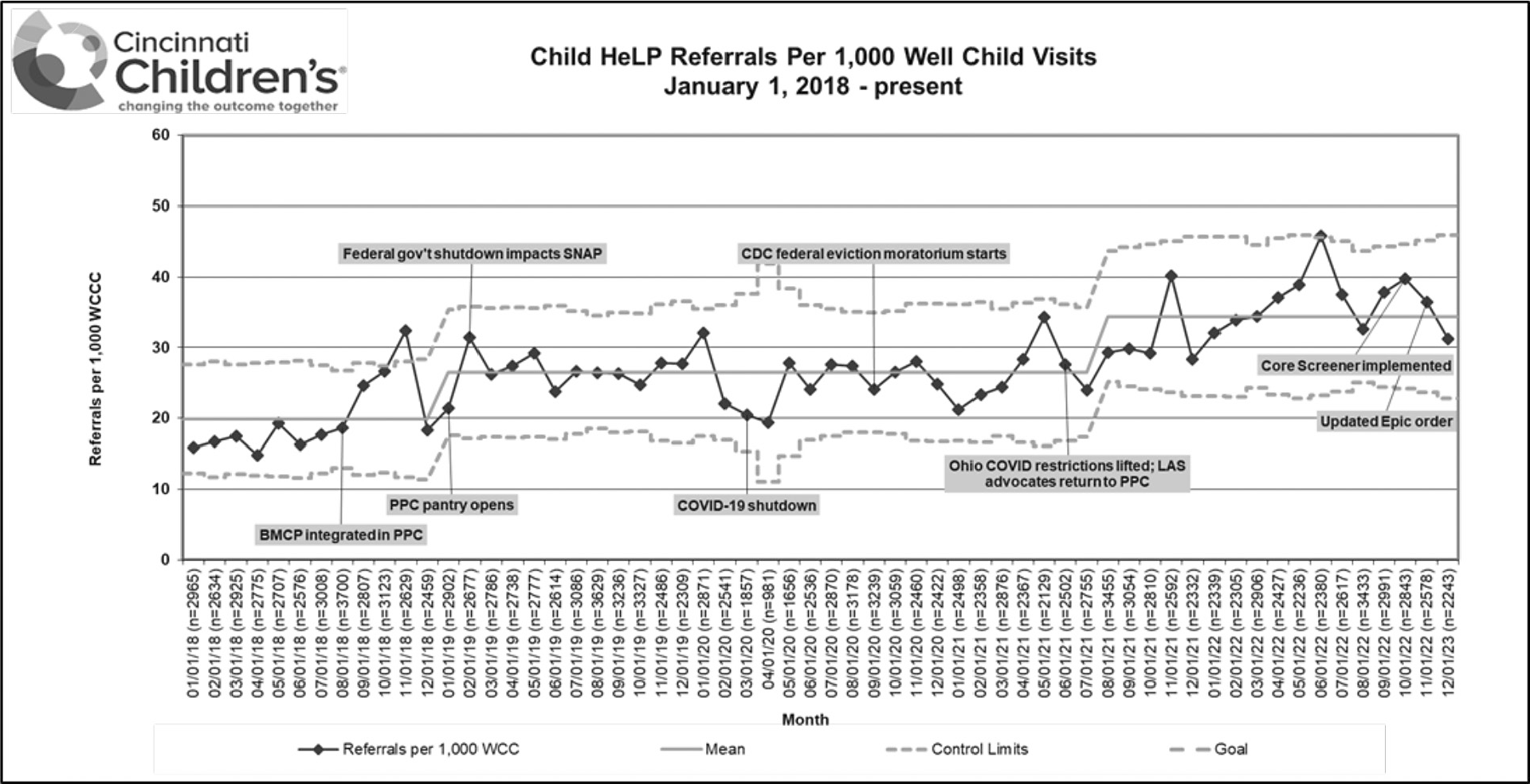

We review updated SPC charts at management meetings. Figure 3 displays Child HeLP referrals per month, from January 2018 through December 2022. Each point represents the monthly referral rate per 1,000 well-child visits. The center red line is the mean, and the dotted red lines are control limits, calculated from the distribution of data points. The annotations mark changes made within our clinical setting and exogenous factors that may have influenced referral numbers. For example, we saw increased referral rates soon after psychologists took a more active role seeing and screening families.

Figure 3 Statistical Process Control chart capturing the rate of referrals to the Cincinnati Child Health-Law Partnership (Child HeLP) each month, measured per 1,000 well-child visits

Abbreviations: BMCP – Behavioral Medicine & Clinical Psychology; CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Child HeLP – Cincinnati Child Health-Law Partnership; PPC – Pediatric Primary Care; SNAP – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

We also stratify data by clinic site. Although our three clinics share a management structure, some common providers, and similar patient populations, there are important differences between them. The clinics are in different locations, of different sizes, with slightly different clinic processes, different numbers and types of trainees, and sociodemographic and cultural differences in patients that present. Importantly, our largest clinic site is the only one with co-located Child HeLP partners. Finally, Figure 4 looks at similar charts focused on our most common case types: public benefits, housing, and education. Each of these charts are used in management meetings. They are also the basis for QI initiatives, highlighting when we need to modify key Child HeLP processes.

Figure 4 Small multiple approach, using Statistical Process Control charts to capture the rate of referrals to the Cincinnati Child Health-Law Partnership (Child HeLP) each month, measured per 1,000 well-child visits, for our most common reasons for referral – a) Public benefits; b) Housing; and c) Education

Abbreviations: Child HeLP – Cincinnati Child Health-Law Partnership; PPC – Pediatric Primary Care

Population-Level Pattern Recognition and Advocacy

By looking at data together, with both medical and legal perspectives, we have been able to identify patterns that move us from patient to population. Indeed, our approach to co-management using QI principles, including data tracked over time, has helped us move beyond a single patient or case. Two cases highlight how individual-level encounters led to system-level changes.

In 2017, multiple families were referred to Child HeLP because they were struggling to add their infants to their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. The data suggested an increase in public benefit cases, particularly in families with young infants. The Child HeLP team identified a root cause — an outdated, unnecessarily cumbersome application process. Legal partners worked with the county public benefits agency to dismantle this process. In addition, Child HeLP’s advocacy led to the creation of a mechanism for Medicaid managed care providers to enter birth information directly into the public benefits computer system, enrolling babies in SNAP, Medicaid, and Cash Assistance simultaneously. This sped up the enrollment process for those referred to Child HeLP and for all applicants in Hamilton County, Ohio by days or even weeks. The value of this local innovation was soon recognized by the state, leading to similar state-level changes. It had emerged from experience on the front line, shared insights by medical and legal partners, and data viewed over time.

The second example case relates to housing. In Summer 2009, a family was referred to Child HeLP for pest infestation and water leakages. Soon, an additional 15 families were referred with similar complaints. The housing team at legal aid who took these referrals identified that all 16 families lived within a portfolio of buildings owned by a single out-of-town developer. This team then helped form a tenant association to advocate for repairs and mitigation. The medical team proactively identified additional patients within the practice who lived in these buildings and connected them to the tenant association — a capability that was possible given the data sharing infrastructure Child HeLP relied upon. Advocacy resulted in new roofs, pest management, and refurbishment of air-conditioning and ventilation systems for nearly 700 low-income housing units in the affected buildings. More recently, we have sought to systematize such pattern recognition through case reviews, data overlays (e.g., housing and health), and routine engagement with local governments and community-based organizations.

The need to identify patterns and support families at a population level has never been more evident. From the early days of the pandemic, Child HeLP’s medical and legal partners regularly communicated about how best to support families’ urgent needs, especially around food, housing, and remote education. Legal partners prepared educational materials to help medical partners advise families how to access critical rent and utilities assistance. They also mobilized a team internal to LASGC to triage housing referrals and ensure that high-priority concerns were handled expeditiously. Medical partners communicated needs most expressed by patients across pandemic phases. Medical partners also provided guidance to legal partners about when and how they could safely return in-person to clinic.

Adapting the Child HeLP Model to Additional Clinical-Community Partnerships

Our approach to additional clinical-community partnerships has been informed by the Child HeLP experience. For example, our Cincinnati Children’s primary care centers and a large regional foodbank came together with a shared goal of reducing the number of food insecure families with children in Greater Cincinnati. As a start, foodbank partners noted they had access to formula but limited ability to access households with infants in need of it. Clinical partners identified that families with infants often reported that they had to stretch their formula supply to make it last; however, the clinic rarely had supply to give. Much as medical and legal partners saw a need that could be better addressed together than apart, foodbank and clinical partners saw an opportunity to leverage strengths of each organization, alongside common populations and objectives. The clinic could distribute formula, supplied by the foodbank, to food insecure households with infants, along with information on additional resources the foodbank supplied in the community.Reference Burkhardt, Beck, Kahn and Klein16 Like Child HeLP, data for improvement was core to our co-management approach. We assessed outcome and process measures relevant to the partnership. In doing so, we determined that infants who received formula were more likely to complete preventative services (e.g., lead and developmental screens). This finding helped us expand our formula program to other clinics. We were also able to work with our foodbank partner to open food pantries within the clinical setting, identifying these new opportunities for joint innovation.17

Summary

Our multidisciplinary MLP uses data-driven QI methods to co-manage and optimize our partnership. Key elements of strong partnerships like Child HeLP need to be established early and revisited frequently. We began by identifying that medical and legal partners served similar populations and had shared objectives. We translated this into short- and long-term goals with operationalized measures and plans for QI. Transparent data sharing between organizations and use of those data for learning and action allow for operationalization of actionable measures promoting innovation and adaptation. Data tracked over time can be used to efficiently address problems that arise and inform new goals or opportunities. We use such data to set the tone for weekly touch-points between a Cincinnati Children’s program manager and LASGC coordinator and for our monthly management team meetings. Such regular check-ins that have clear, shared agendas and are guided by data have allowed our team to be more effective and efficient.18

Growing Child HeLP has taken time and buy-in from key individuals in both organizations and, ultimately, from our patients and clients. We have found that developing a deep understanding of one another’s organizations, and local context, has been critical. What populations are served? What are the central objectives or missions of each organization? What do intervention processes look like? How might processes be merged between both organizations and made more efficient? Answers to such questions can help to identify partners, prioritize objectives, and develop action steps built atop shared theory. Data tracked over time, using SPC methods, can help evaluate interventions, answering questions and identifying relevant new questions, more quickly.Reference Reichman, Brachio, Madu and Montoya-Williams19

We see a bright future for Child HeLP, for MLPs, and for clinical-community partnerships generally. We suggest that such a future is made brighter when partnerships are optimized using data-driven, rigorous methods. Such methods are proving useful as we seek to extend the reach of Child HeLP, and our other partnerships, to new clinics and to train new providers. Nearly 100 pediatric residents and medical students rotate through our primary care centers. They receive regular education about social (and legal) needs and about the effects MLPs can have on patient and population health.

A moral imperative to address health-harming legal needs is increasingly augmented by financial incentives. Cincinnati Children’s recently contracted with a large Medicaid Managed Care Organization in Southwest Ohio to assume risk for the health of ~120,000 children through an Accountable Care Organization, enabling innovations in care delivery. In the last year alone, ~70% of Child HeLP referrals were for children covered under this value-based initiative. Driven by evidence of impact embedded in the data we have generated through Child HeLP,20 we have set up a pilot whereby our Accountable Care Organization is now contributing to existing and expanding services. Although this payer is not yet fully funding operating dollars, it is an important step in that direction. With existing data sharing capabilities, and with growing data linkages with the Accountable Care Organization, we anticipate evaluation will be a key component of this emerging medical-legal-payer partnership.

Conclusion

Unmet legal needs negatively influence health outcomes. MLPs, which connect medical and legal partners to address such needs, can meaningfully improve health outcomes — but they are only as effective as their partnership is strong. The strength and adaptability of MLPs require a dedicated approach to co-management, one that is built on trust and aligned on objectives. QI methods, and data on pertinent process and outcome measures, facilitate the identification of problems and patterns in more efficient ways.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank partners in the Pediatric Primary Care Centers of Cincinnati Children’s and advocates at the Legal Aid Society of Greater Cincinnati as they have been vital to the development and lasting impact of our program. This work was also supported, in part, by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 1R01HS027996).