Historically, sponsors and regulatory agencies have kept confidential much of the clinical data generated to support the approval and continued monitoring of small molecule and biologic drugs (i.e., regulatory data). Notable cases, such as rofecoxib (Vioxx) and gabapentin (Neurontin), revealed how treating data as confidential can conceal important information about drug safety and efficacy, as well as improper research practices, including the selective publication and reporting of trial results.Reference Krumholz, Ross, Presler and Egilman 1 Providing access to these data may not only help prevent unscrupulous research practices, but also advance our understanding of the safety and effectiveness of medical products.Reference Bernard 2

Over the past two decades numerous initiatives have been launched to make regulatory data, including clinical study reports (CSRs) and individual patient-level data (IPD), publicly available.Reference Dey, Ross, Ritchie, Desai, Bhavnani and Krumholz 3 For instance, there are data sharing initiatives organized by industry (e.g. ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com [CSDR]) and independent organizations (e.g. Yale University Open Data Access [YODA] Project). 4 While these efforts have advanced transparency for many medical products,Reference Vaduganathan, Nagarur, Qamar, Patel, Navar and Peterson 5 they have not gained traction industry-wide and remain constrained by their lack of authority to require companies to make data publicly available.Reference Hopkins, Rowland and Sorich 6 In contrast, regulatory agencies, as gatekeepers of market authorization, are best positioned to disclose data, particularly clinical data submitted for regulatory review.

Several laws and policies — some recent — authorize the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe, Health Canada (HC) in Canada, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States to make clinical data of drugs publicly available, either proactively or reactively in response to information requests. These data (Box 1), such as clinical summaries, CSRs, individual case safety reports, and other information sponsors must submit to regulators, contain substantially more information than published articles and can be used to more comprehensively ascertain the risks and benefits of drugs, assess regulatory decisions, and inform clinical decision making.Reference Schroll, Penninga and Gøtzsche 7

Box 1 Categories of regulatory data

IPD=individual patient-level data.

a Definitions were adapted from EMA’s definitions of regulatory data. 37

While regulatory data have been relied on for many studies, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses,Reference Jefferson, Jones, Doshi, Spencer, Onakpoya and Heneghan 8 there is substantial opportunity to increase use of regulatory data for secondary research.Reference Hodkinson, Dietz, Lefebvre, Golder, Jones and Doshi 9 For example, one survey found that only 3% of authors of Cochrane Reviews obtained data from regulatory agencies. 10 Raising awareness of the scope of clinical data made available across the EMA, HC, and FDA, and the most efficient ways to obtain it, may increase the use and utility of clinical research data for patients, clinicians, and researchers.

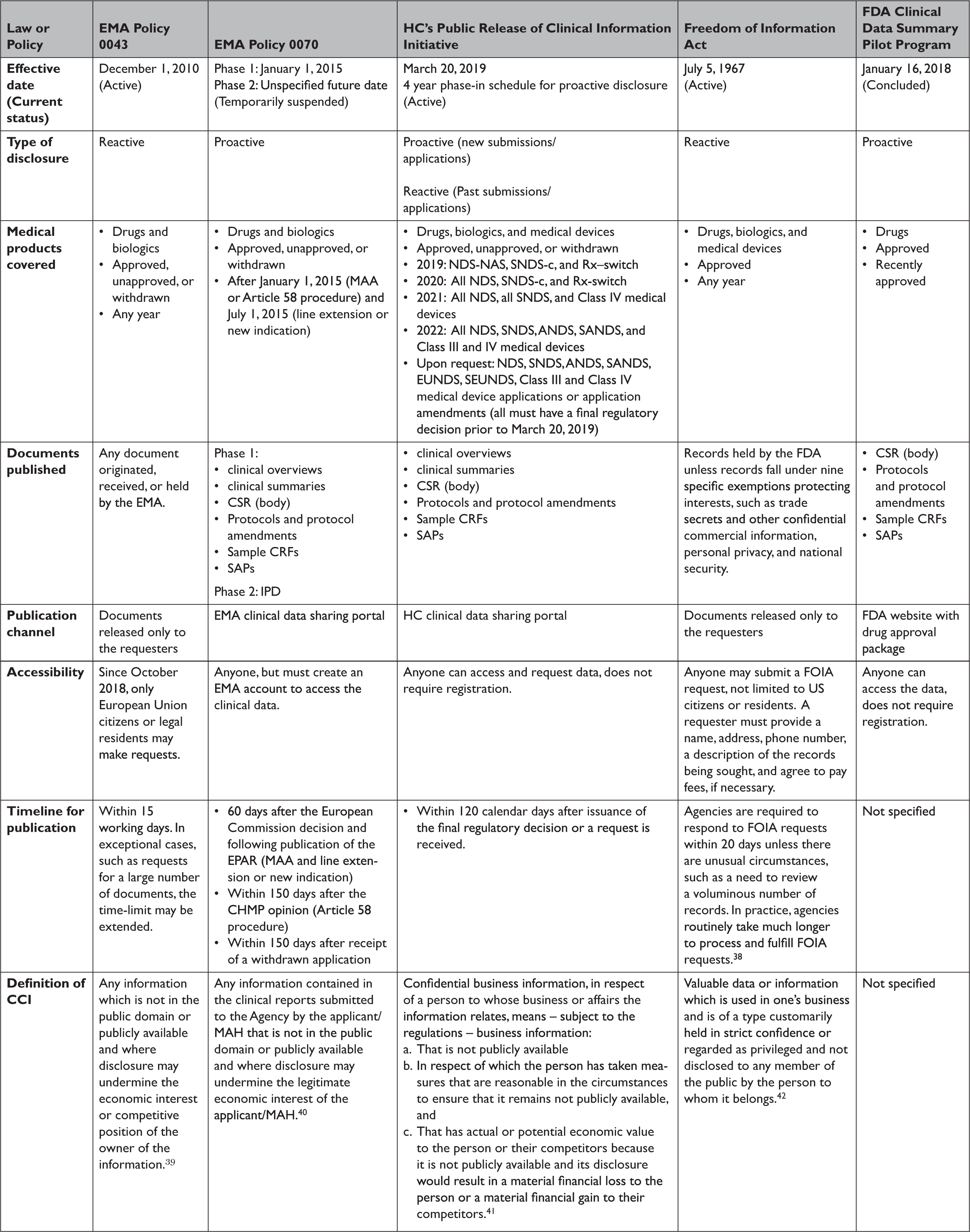

In this analysis, we provide an overview of the key laws and policies governing disclosure of data at the EMA, HC, and FDA, including how each regulator defines certain data as “confidential commercial information” (CCI) that may be kept secret. Based on a review of agency data sharing portals, published research on information requests, and our own parallel information requests, we then compare the accessibility and comprehensiveness of data proactively disclosed and made available upon request by the EMA, HC, and FDA. Lastly, we propose ways for these regulatory bodies to enhance transparency.

In this analysis, we provide an overview of the key laws and policies governing disclosure of data at the EMA, HC, and FDA, including how each regulator defines certain data as “confidential commercial information” (CCI) that may be kept secret. Based on a review of agency data sharing portals, published research on information requests, and our own parallel information requests, we then compare the accessibility and comprehensiveness of data proactively disclosed and made available upon request by the EMA, HC, and FDA. Lastly, we propose ways for these regulatory bodies to enhance transparency.

Transparency Laws and Policies European Medicines Agency

Policy 0043 and Policy 0070 govern the EMA’s approach to providing access to regulatory data for drugs and biologics (Table 1). Policy 0043, adopted in 2010, authorizes the EMA to release data reactively. 11 Policy 0070, adopted in 2014, authorizes the EMA to proactively publish data on an online data sharing portal. 12 The scope of policy 0043 is expansive, providing access to any document originated, received, or held by the EMA. The scope of Policy 0070 is narrower, applying only to data submitted under the central marketing authorization procedure after January 1, 2015. EMA plans to implement Policy 0070 in two phases. Phase 1 publishes clinical reports, which include clinical overviews, clinical summaries, CSRs, along with several appendices to the CSRs, including protocol and protocol amendments, sample case report forms (CRFs), and statistical analysis plans (SAPs). Phase 2 will publish IPD. However, in 2018 EMA temporarily suspended its proactive publication of data, citing the disruption and resource constraints caused by the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union. 13

Table 1 Characteristics of transparency laws or policies across the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and US Food and Drug Administration

ANDS=abbreviated new drug submission; CCI=confidential commercial Information; CHMP=Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use

CRF=clinical report form; CSR=clinical study report; EMA=European Medicines Agency; EPAR=European public assessment report; EUNDS=extraordinary use new drug submissions; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; HC=Health Canada; IPD=individual patient-level data; MAA=market authorization application; MAH=market authorization holder; NAS=new active substance; NDS=new drug submission; Rx-switch=submissions to switch an authorized medicinal ingredient to non-prescription status; SANDS=supplemental abbreviated new drug submissions; SAP=statistical analysis plan; SEUNDS=supplemental extraordinary use new drug submissions; SNDS-c=supplemental new drug submission containing confirmatory trials; SNDS=supplemental new drug submission.

EMA’s proactive and reactive disclosure policies take a similar position on CCI, generally considering information contained in clinical reports not as CCI, unless disclosure undermines the competitive position of the information’s owner. This position faced several challenges in court but was recently validated by the European Court of Justice. The Court found that clinical reports were not covered by a general presumption of confidentiality and that market authorization holders must meet a high standard to qualify any data included in the reports as CCI, by establishing that disclosure poses the risk of concrete harm to their commercial interests. 14 Additional details regarding data accessibility and the timeline for data publication are available in Table 1.

Health Canada

In March 2019, HC launched its Public Release of Clinical Information (PRCI) initiative, which goes beyond EMA Policy 0070 by proactively releasing data for not only approved, unapproved, and withdrawn drug and biologic submissions but also Class III and IV medical device applications (Table 1). 15 The clinical data made available is similar in scope to EMA Policy 0070, with HC publishing clinical reports. HC also intends to make clinical reports available upon request for medical products that had a final regulatory decision prior to March 2019, similar to Policy 0043. However, HC will not release IPD under the PRCI initiative. HC plans to phase in the proactive release of clinical reports over four years, beginning in 2019.

HC construes CCI (known as “confidential business information” in Canada) narrowly, protecting only clinical information not used by the applicant to support the proposed conditions of use or clinical information that describes tests, methods, or assays used exclusively by the manufacturer, and then only with adequate justification. 16 Going forward, HC aims to publish data within 120 days after issuance of a final regulatory decision or after an information request is lodged. Unlike the EMA, data posted in response to information requests are made available on HC’s online portal, requests are not limited to the citizens of the nation’s regulator (i.e. Canadians), and registration is not required to access data.

US Food and Drug Administration

In January 2018, FDA launched a new pilot program to proactively publish CSRs of pivotal studies for nine recently-approved novel drugs, including trial protocols, protocol amendments, and SAPs (Table 1). 17 However, FDA announced in March 2020 that it was ending the pilot, with only a single CSR having been made available. 18

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), enacted in 1966, requires federal agencies, including the FDA, to disclose records upon request by the public, unless records fall under one of nine specific exemptions protecting interests such as CCI and personal privacy. 19 FOIA is the only mechanism to access certain types of regulatory data, such as CSRs, for medical products approved by the FDA.Reference Egilman, Wallach, Morten, Lurie and Ross 20 The FDA has defined CCI as “valuable data or information which is used in one’s business and is of a type customarily held in strict confidence or regarded as privileged and not disclosed to any member of the public by the person to whom it belongs.” 21 However, even if information meets the definition of CCI, FDA may have discretion to release it if there is a compelling public interest in disclosure.Reference Kapczynski and Kim 22

Assessing Proactive Disclosure of Regulatory Data

To assess the EMA and HC’s proactive publication of clinical data under Policy 0070 and the PRCI initiative, respectively, we systematically searched each agency’s online data sharing portal, 23 documenting for each data release through April 2021: the type of medical product (drug, biologic, medical device, or vaccine); regulatory procedure (initial marketing authorization application (MAA) or post-authorization application); regulatory decision (approved, unapproved, or withdrawn); regulatory decision date; public release date; and time from regulatory decision to release. EMA and HC generally release the same categories of data across medical product types and regulatory procedures. Thus, to compare the data released across agencies, we randomly selected a single product for which both EMA and HC had made clinical data available, and then characterized the category of data released, number of pages, presence of redactions, reason for redactions provided (protected personal data (PPD) or CCI), and described the information redacted.

Assessing Reactive Disclosure of Regulatory Data

To assess EMA, HC, and FDA’s reactive data disclosure processes, we first reviewed the literature to identify studies on information requests submitted to EMA, HC, or FDA. To better understand the scope of data made available by EMA, HC, and FDA in response to information requests, we submitted a FOIA request to FDA in 2014 for a wide range of clinical data and regulatory records for Gilead’s Hepatitis C drugs sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni) (Appendix Box 1), as well as a parallel request to EMA in 2016 under Policy 0043 and to HC in 2020 under the PRCI initiative. Sovaldi and Harvoni were selected as illustrative test cases because of their novelty, the safety issues that were being evaluated at the time we initiated this work, their use in the treatment of Hepatitis C, a major global health problem, and high cost.Reference Fontaine, Lazarus, Pol, Pecriaux, Bagate and Sultanik 24 We documented the date of each request milestone (e.g. initial request filed, appeal filed) and the date of each document production. For each production, we then characterized the category of data and the number of pages made available. We then described the information that had been redacted and compared the number of pages and redactions in CSRs of phase 2 and 3 trials produced by EMA, HC, and FDA.

Since HC releases information in response to requests on the same online data sharing portal as the information it proactively discloses, we followed the same methodology (described above) for extracting information on HC’s reactive disclosure as we did for the agency’s proactive disclosure.

Findings: Proactive Disclosure of Regulatory Data

Between 2016 and April 2021, EMA proactively released data for 123 unique medical products (Appendix Table 1), including 81 drugs, 38 biologics, and 4 vaccines (Table 2). Data supporting 147 regulatory procedures reviewed by the EMA between 2015 and 2021 were made publicly available, including 95 initial MAAs and 52 post-authorization applications; of which 135 were approved and 12 were withdrawn. Between 2019 and April 2021, HC proactively released data for 73 unique medical products, including 45 drugs, 23 biologics, 3 vaccines, and 2 medical devices. HC disclosed data supporting 62 initial MAAs and 13 post-authorization applications; all 75 were approved between 2016 and 2021. In 2018, FDA proactively disclosed data supporting the initial MAA of 1 drug that was approved in 2018. EMA, HC, and FDA took a median of 511 (interquartile range 416-574), 150 (interquartile range 122-204), and 33 days, respectively, after each agency’s regulatory decision to release data.

Table 2 Characteristics of the medical products in which the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and US Food and Drug Administration have proactively made data available through April 2021

EMA=European Medicines Agency; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; HC=Health Canada; IQR=interquartile range.

a Alternative formulations were combined, along with generics or biosimilars with original products.

b For HC, initial marketing authorization includes new drug submission-new active substances (n=42), new drug submissions (n=15), Class III medical devices (n=1), Class IV medical devices (n=1), and 2 vaccines and 1 biologic authorized under Interim Order (n=3). For FDA, initial marketing authorization includes 1 new drug application.

c For EMA, post-authorization includes extension of indications (n=45), line extensions (n=5), and workshare (n=2) procedure types. For HC, post-authorization includes supplemental new drug submissions (n=2) and supplemental new drug submissions containing confirmatory trials (n=11).

d For EMA, dates of two post-authorization procedures were unavailable, and were excluded from processing time calculations.

e EMA’s temporary suspension of Policy 0070 remains in place, however, clinical data for these 5 medical products were published in line with EMA’s exceptional measures to maximize the transparency of its regulatory activities on treatments and vaccines for Coronavirus Disease 2019 that are approved or are under evaluation.

f One biologic and one medical device package proactively released by HC were identified as part of the agency’s pilot program and thus were excluded from processing time calculations.

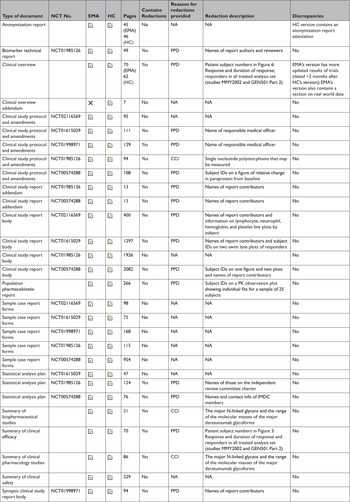

At the time of initial data collection (April 30, 2020), no data supporting the same MAA were proactively released by both EMA and HC. However, data supporting the same initial MAA for 4 medicines were made available proactively by EMA and reactively by HC. After reviewing HC’s data releases and confirming the agency typically makes available equivalent categories of information proactively and reactively, we randomly selected daratumumab (Darzalex) among those 4 medicines to compare the information shared across EMA and HC. EMA and HC released 28 and 29 documents, respectively, for Darzalex, including all of the same categories of data: a clinical overview; summaries of biopharmaceutical and pharmacological studies, summaries of safety and efficacy, a biomarker technical report, and a population pharmacokinetic report; for each of its 5 clinical trials: a CSR (4 full, 1 synoptic), protocol and protocol amendments, sample CRFs, and SAPs for 3 of the trials (Table 3). There were no substantive discrepancies in the released data. However, EMA disclosed a more updated clinical overview, while HC posted an additional clinical overview addendum describing Canadian treatment approaches for multiple myeloma. The full CSRs, protocols, including those with amendments, CRFs, and SAPs had a median length of 1612, 108, 115, and 76 pages, respectively, for both EMA and HC. Redactions were comparable and minimal across EMA and HC: PPD and CCI were provided as the reasons for redactions in 3 and 15 documents, respectively. Names of report investigators or subject ID numbers were the most common redactions.

Table 3 Comparison of the data made available by the European Medicines Agency and Health Canada. A case study of daratumumab (Darzalex)

CCI=confidential commercial information; EMA=European Medicines Agency; HC=Health Canada; NCT=national clinical trial; PK=pharmacokinetic; PPD=protected personal data.

Findings: Reactive Disclosure of Regulatory Data

We identified two studies on information requests to EMA under Policy 0043, no studies on information requests to HC under the PRCI initiative, one study on FOIA requests to FDA, and one study examining CSRs released in response to information requests to EMA and FDA, among other sources. One study determined that of the 457 information requests EMA received between 2010 and 2012, 66% were granted, 27% were denied, and 7% were pending.Reference Doshi and Jefferson 25 Requests were processed in a median of 26 days. In a case series of 12 information requests filed between 2011 and 2015, the EMA released a wide variety of regulatory data, including CSRs, regulatory comments, meeting and decision records, periodic safety update reports, correspondence, and postmarket data and took a median of 301 days to process the requests.Reference Doshi and Jefferson 26 A study examining 78 CSRs, including 11 obtained from information requests to EMA and FDA, found that key appendices of CSRs, such as protocols and case report forms were frequently omitted.Reference Doshi and Jefferson 27 Based on a study of FOIA requests to FDA between 2008 and 2017, FDA fully or partially granted 72% of requests. 28 FDA processed one-fifth of requests in 20 days but took more than 61 days to process two-thirds of requests.

HC released data for 55 unique medical products in response to 70 processed requests between February 2019 and April 2021, including for 23 drugs, 6 biologics, 6 vaccines, and 20 medical devices. HC took a median of 132 (interquartile range 103-167) days to process requests and published the same categories of regulatory data reactively as it had proactively.

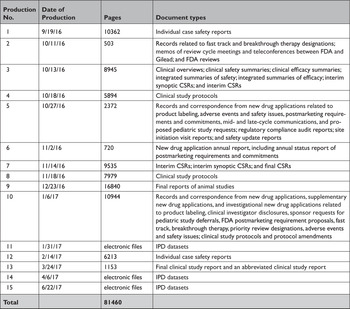

In response to our parallel requests for information supporting approval of Sovaldi and Harvoni, FDA and HC released substantially more regulatory data than EMA, including clinical overviews, summaries and integrated summaries of safety and efficacy, clinical study protocols and amendments, and narratives of deaths and serious adverse events. Information only made available by FDA include individual safety case reports; records and correspondence related to product labeling, safety concerns, pediatric studies, expedited approval pathway designations, and postmarket study requirements and commitments; safety update reports; site initiation visit reports; and IPD, albeit heavily redacted (Appendix Table 2). Information only produced by HC include sample case report forms and statistical analysis plans (Appendix Table 3). Information only made available by EMA include periodic safety update reports and pharmacovigilance risk assessment committee reports (Appendix Table 4).

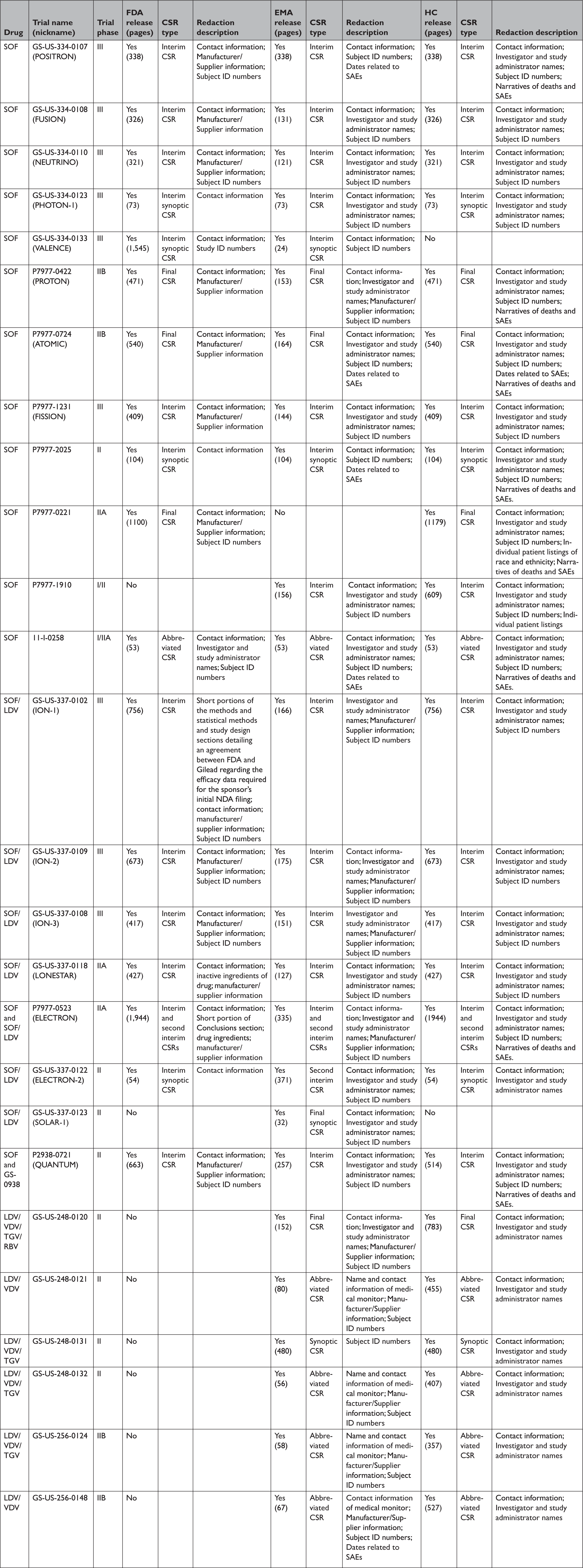

All three agencies made available CSRs for phase 1, 2, and 3 trials. Comparing the productions of CSRs of phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, EMA released CSRs corresponding to more phase 2 and 3 trials than FDA and HC (25 vs. 18 vs. 24); however, of the 16 CSRs produced for the same clinical trials by all three regulators, 11 released by FDA and HC were longer, 4 were the same, and 1 released by EMA was longer (Appendix Table 5). Among the 16 CSRs, those produced by FDA had an average of 473 pages compared to 464 and 179 pages for those produced by HC and EMA, respectively. EMA, HC, and FDA redactions of the CSRs were minimal, most commonly redacting names and contact information of study investigators and administrators and subject ID numbers. EMA and FDA also commonly redacted information about the drug manufacturer and supplier, citing CCI, while HC redacted narratives of deaths and serious adverse events, citing PPD. Time from initial request to final data production was 918 and 968 days for FDA and EMA, respectively (Appendix Table 6). While HC processed the information request much faster, publicly posting the data packages for Harvoni and Sovaldi 155 and 351 days, respectively, after the initial request. The request to FDA required considerably more resources, including multiple appeals and court filings. Additionally, FDA waived processing fees; however, the agency normally charges fees unless it is shown disclosure of the requested information is in the public interest. 29 Last, HC organizes its data productions into categories, making the information much easier to navigate and process.

Enhancing Regulatory Data Transparency in the 2020s

Over the past decade, EMA and HC have greatly expanded the public availability of regulatory data, while FDA has lagged behind by not proactively publishing clinical reports. EMA and HC’s routine publication of clinical reports, including clinical overviews and summaries, CSRs, protocols, sample CRFs, and SAPs, which just a decade ago had largely been treated by regulators as CCI, represents a paradigm shift in clinical trial transparency. HC’s more recent PRCI initiative goes beyond EMA Policy 0070 in proactively posting clinical reports supporting medical device applications, not just drug and biologic MAAs. HC also offers the most efficient source of regulatory data, typically posting clinical reports about 5 months after a regulatory decision, nearly a year quicker than EMA, and processing most information requests in less than 5 months, about 150 days quicker than EMA takes to release requested regulatory data that are complex or voluminous. 30 EMA and FDA required nearly three years to process our request for comprehensive regulatory data supporting the approvals of Sovaldi and Harvoni, substantially longer than EMA had previously taken to process requests for CSRs. 31

While EMA and FDA processing times vary widely, 32 our findings suggest there may be an opportunity for EMA and FDA to increase their processing speed to align with HC. The CSRs released upon request by FDA and HC were more than double the length of those produced by EMA, suggesting FDA and HC may source more comprehensive CSRs. A similar request to FDA may require greater resources than to EMA and HC. Nonetheless, use of EMA or FDA’s information request processes may be necessary to gain access to other types of regulatory data, such as sponsor-regulator correspondence. Consistent with findings from other recent studies, redactions across the agencies were mostly minor (e.g., primarily researcher and participant identifying information) and generally did not impede interpretation of the evidence. 33 Two notable exceptions are FDA and HC’s complete redaction of IPD and narratives of serious adverse events and deaths, respectively.

Our study has several limitations. First, HC’s start date, the date when HC initiates the process to prepare information for public release, was used to calculate HC’s processing time for information requests, not the actual date information requests were submitted, which is not publicly available. HC may take several weeks, and in some cases months, to begin processing requests, particularly when a request requires clarification or where paper records need to be digitized. Therefore, HC may take moderately longer than a median of 132 days to process requests. However, it is unlikely to impact the study’s finding that HC is the most efficient source of clinical reports, given EMA required a median of 301 days to process a series of comparable information requests and HC also completed our requests for information on Sovaldi and Harvoni in about one-third the time that EMA and FDA required. 34 Second, parts of the study were based on analyses of case studies, including Sovaldi, Harvoni, and Darzalex, which represent just a few of the many medical products for which data has been made publicly available. Third, the length of CSRs was used to compare the scope of data made available reactively by each agency; specific differences in the content of CSRs were not examined. Last, the study was limited to transparency of regulatory data, which comprises just a portion of data generated in clinical trials. Given the progress government agencies have made toward transparency of regulatory data, non-governmental led data sharing initiatives, such as the YODA Project, might consider shifting their focus and resources toward advancing data transparency of trials not submitted to regulators (e.g., academic trials).

While clinical reports and other categories of regulatory data supporting MAAs of drugs, biologics, and medical devices have been made accessible, there are several ways regulators could enhance transparency over the next decade. First, EMA and FDA should mitigate or remove barriers to accessing clinical reports, including citizenship requirements and processing costs associated with information requests, particularly for those requesting information in the public interest. Second, to improve access to information, EMA and FDA should post requested clinical data on a public online portal and increase their processing speed to more closely align with HC. To reduce delays, regulators should consider hiring more personnel and devoting greater resources to responding to requests. Third, EMA and FDA should extend access to data supporting medical devices. Last, while EMA remains committed to make available IPD in Phase 2 of Policy 0070, FDA and HC also should implement policies to share IPD, which would provide the raw data necessary to conduct secondary analyses. While sharing IPD poses increased risks of patient reidentification, data sharing initiatives, such as the YODA Project and CSDR, have demonstrated that through use of a “trusted intermediary,” regulatory agencies could share IPD with researchers to maximize the use and utility of the data while still protecting patient privacy.Reference Ohmann, Banzi, Canham, Battaglia, Matei and Ariyo 35

The administrative and redaction costs incurred by industry and regulatory authorities represent a substantial obstacle to the future of clinical data sharing programs, exemplified by the ongoing, albeit temporary, suspension of Policy 0070 and the restriction of information requests to EMA to EU citizens and legal residents in 2018. To address this challenge, governments and institutions, such as the European Union, should give greater priority and funding to regulatory data sharing programs. Concurrently, efforts to improve the efficiency of data sharing initiatives should be considered. For instance, multiregional disclosure requirements with varying anonymization standards for CCI and PPD increase costs. Regional regulators may consider a harmonized approach for clinical report disclosure to help reduce inefficiencies. In fact, HC has already begun accepting clinical information previously published under Policy 0070 for its PRCI initiative. Also, FDA recently announced that sharing of CSRs in harmony with international regulators is a long-term goal. 36 However, an important benefit of a multiregional approach is that it encourages greater transparency by incentivizing sponsors to anonymize data in accordance with the standards least amenable to CCI claims. For example, we found that names of drug manufacturers and suppliers were often redacted by EMA and FDA, but HC did not consider this information as CCI, and thus pharmaceutical sponsors may be encouraged to not devote resources to redact such information in a multiregional approach, recognizing the data will become public under the PRCI initiative. Therefore, it is important that measures, such as enforcement of HC’s narrower definition of CCI, are taken to prevent harmonization of disclosure standards toward less transparency.

In summary, regulatory data pertinent to public health and clinical medicine that were used to support the approval of medicines and medical devices are now available proactively or in response to information requests. Over the next decade, regulatory agencies should make IPD available, and additional resources might be needed to ensure the long-term viability of regulatory data sharing programs and to encourage researchers to take advantage of the data that is — for now — more available than ever before.

In summary, regulatory data pertinent to public health and clinical medicine that were used to support the approval of medicines and medical devices are now available proactively or in response to information requests. Over the next decade, regulatory agencies should make IPD available, and additional resources might be needed to ensure the long-term viability of regulatory data sharing programs and to encourage researchers to take advantage of the data that is — for now — more available than ever before.

Note

Additional Contributions

We thank John Brinkerhoff, Kathleen Choi, Nora Niedzielski-Eichner, Russell Fink, Darius Fullmer, Gregg Gonsalves, Cortelyou Kenney, Aislinn Klos, John Langford, Amanda Lynch, Jonathan Manes, Catherine Martinez, Yurji Melnyk, Ben Picozzi, Jennifer Pinsof, David Schulz, and Delbert Tran for their contributions to the information requests to EMA and FDA. These individuals pursued this work as students or faculty of Yale Law School and were not compensated for their efforts.

Author Contributions

Mr. Egilman and Dr. Ross had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ACE and JSR contributed to study concept and design; ACE, MEM, and ATL abstracted the data; all authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data; ACE drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript; and JSR provided study supervision.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: In the past 36 months, all of the authors formerly received research support through Yale University from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) at Yale; Mr. Egilman and Drs. Ross and Wallach currently receive support from the Food and Drug Administration for the Yale-Mayo Clinic Center for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program (U01FD005938); Dr. Ross received research support through Yale University from Medtronic, Inc. and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices (U01FD004585) and from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting (HHSM-500-2013-13018I); Dr. Ross currently receives research support through Yale University from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Medical Device Innovation Consortium as part of the National Evaluation System for Health Technology (NEST), from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS022882), from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HS025164, R01HL144644), and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to establish the Good Pharma Scorecard at Bioethics International. Mr. Herder is a member of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, Canada’s national drug price regulator, and receives honoraria for his public service. Mr. Herder also receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT 156256; CMS 171741). Dr. Wallach receives support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award K01AA028258.

Funding

This project was conducted as part of the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) at Yale, funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, which formerly supported all of the authors. The Laura and John Arnold Foundation played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented, which do not represent the views of any supporting institutions.

Ethics approval

This study used publicly available information and did not require ethics approval from the Yale University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Program.

Data availability

Requests for the dataset can be made to the corresponding author at joseph.ross@yale.edu.

Supplementary Appendix

Appendix Table 1 The medical products in which the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and US Food and Drug Administration have made data available through April 2021

EMA=European Medicines Agency; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; HC=Health Canada; P=proactive; R=reactive.

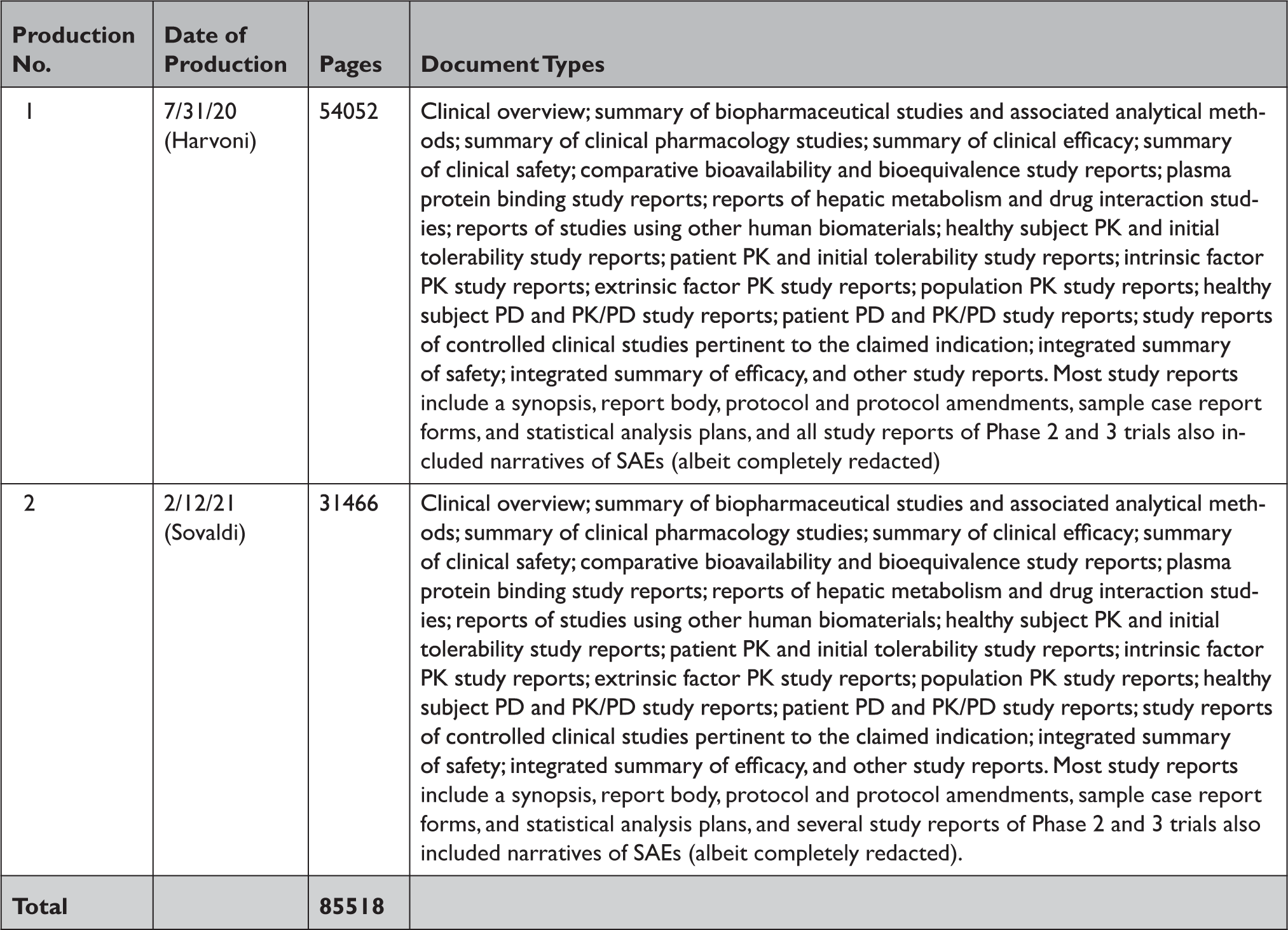

Appendix Table 2 Summary of documents released by the US Food and Drug Administration in response to our Freedom of Information Act request

CSR=clinical study report; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; IPD=individual patient-level data.

Appendix Table 3 Summary of documents released by Health Canada in response to our information requests through the Public Release of Clinical Information initiative

PD=pharmacodynamic; PK=pharmacokinetic; SAE=serious adverse event.

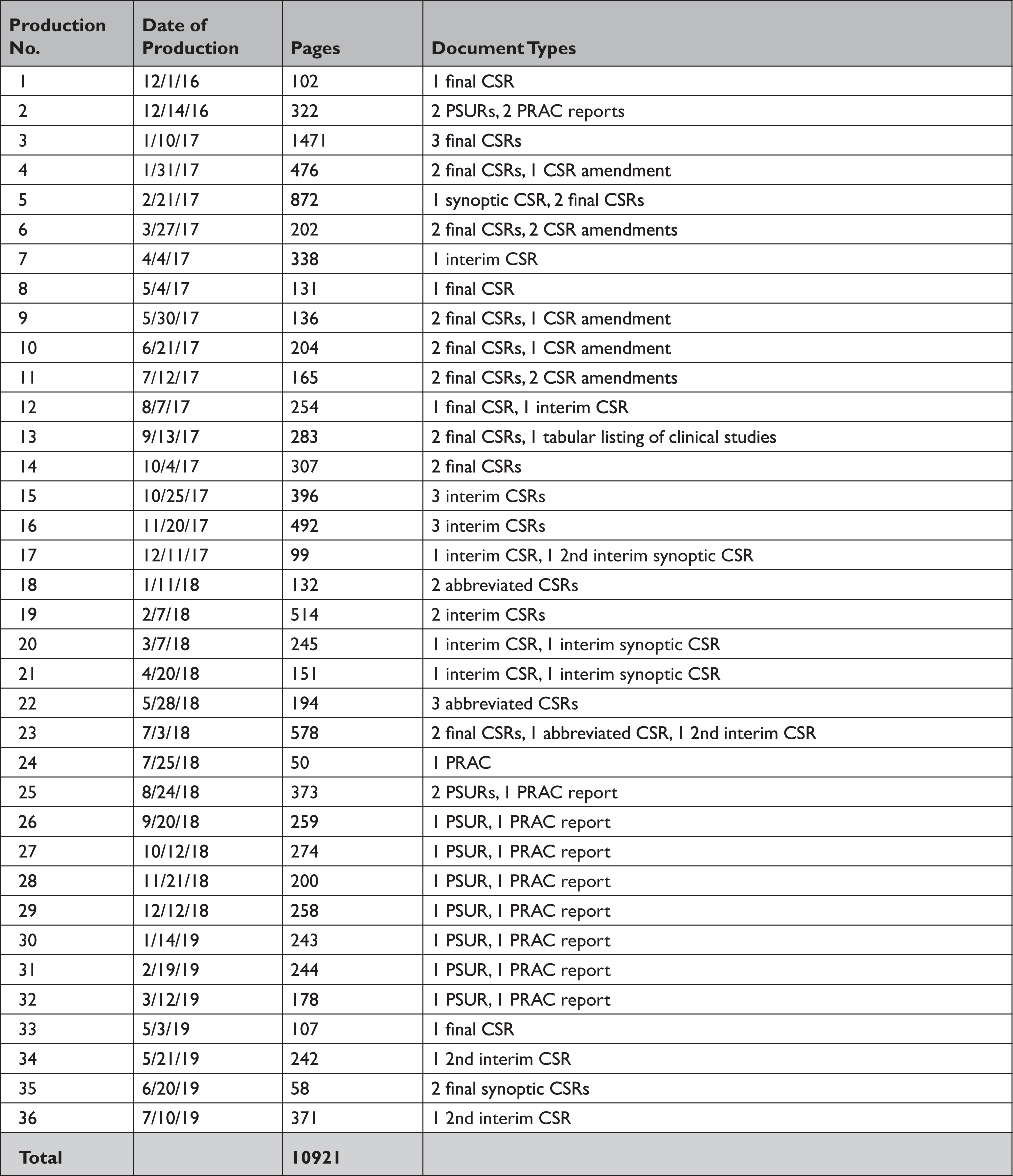

Appendix Table 4 Summary of documents released by the European Medicines Agency in response to our information request under Policy 0043

CSR=clinical study report; PRAC=pharmacovigilance risk assessment committee; PSUR=periodic safety update report.

Appendix Table 5 Comparison of clinical study reportsa of phase 2 and 3 clinical trials released by the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and the Food and Drug Administration in response to our information requests

CSR=clinical study report; EMA=European Medicines Agency; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; HC=Health Canada; LDV=ledipasvir; RBV=ribavirin; SAE=serious adverse event; SOF=sofosbuvir; TGV=tegobuvir; VDV=vedroprevir.

Appendix Table 6 Timeline of milestones for our information requests to the European Medicines Agency, Health Canada, and the US Food and Drug Administration

EMA=European Medicines Agency; FDA=United States Food and Drug Administration; HC=Health Canada.

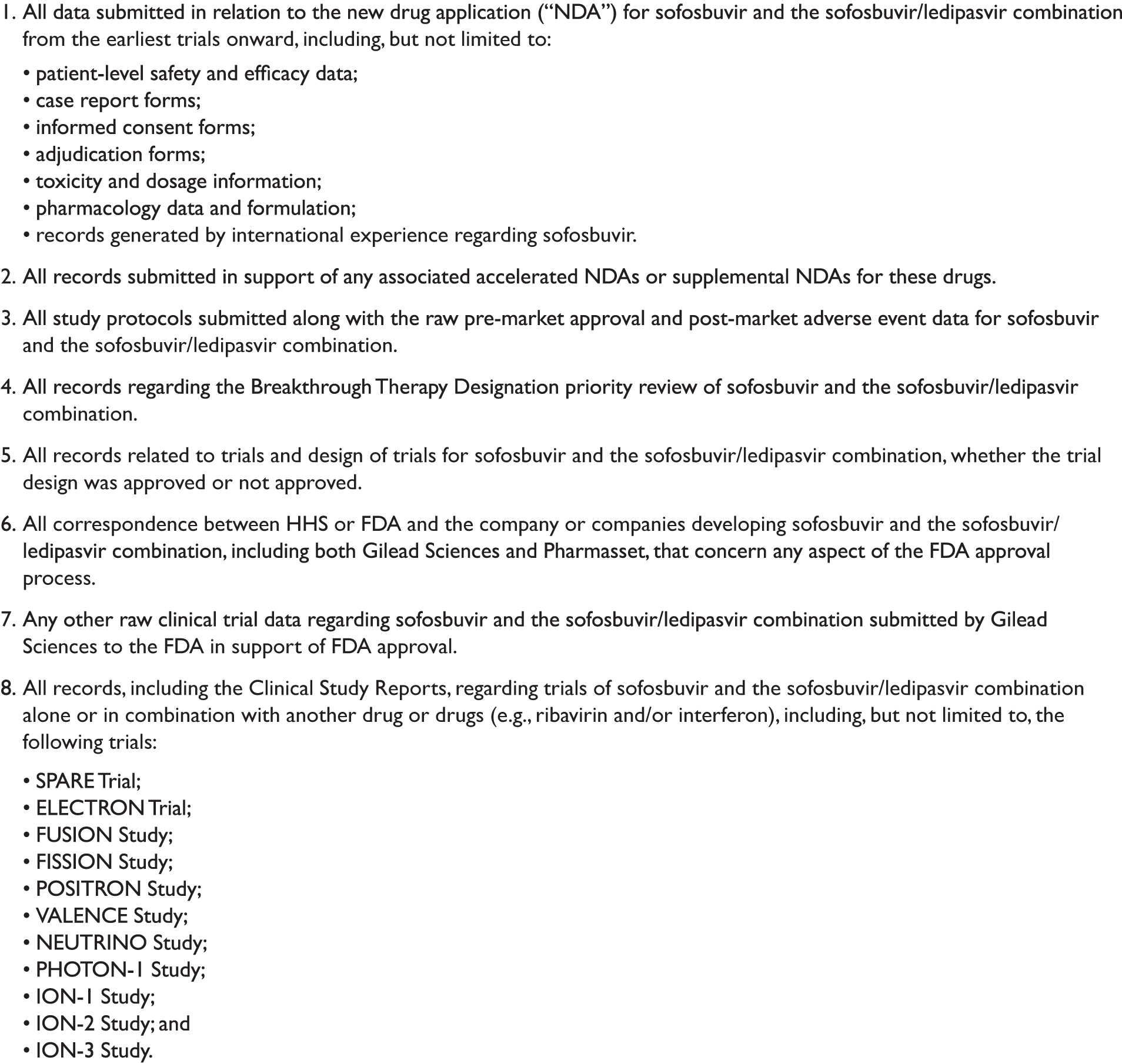

Appendix Box 1 Information requested from the US Food and Drug Administration under the Freedom of Information Act