1. Introduction

One might suppose that a syntactic phenomenon that has been a central focus of research for more than half a century would be well understood and that future research would be essentially a matter of fleshing out a generally accepted picture. Unbounded (or long distance) dependencies (UDs), a central feature of wh-interrogatives, relative clauses, and other unbounded dependency constructions (UDCs), have been a major concern of research in syntax since Ross (Reference Ross1967). and there is a massive literature on the subject. However, there is evidence that UDs are not as well understood as one might suppose and that the most widely assumed approach is seriously flawed.

One might also think that even if there are problems in one area of syntactic research, the basic approach underlying the research must be broadly satisfactory. After all, syntactic theory, as it has developed since Syntactic Structures (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1957). has shed light on many syntactic phenomena in many languages, and its insights have enriched descriptive grammars such as Huddleston & Pullum (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002). However, it does not follow that all is well with modern syntactic theory. In fact, there is evidence that it is problematic in a number of ways.

In the book under review, Rui Chaves and Michael Putnam (henceforth C&P) argue that the dominant approach to UDs is flawed and that it is flawed because the general approach to syntax which it stems from is flawed, and they develop detailed alternatives. There have been many criticisms of mainstream Chomskyan syntax in recent decades (see e.g. Postal Reference Postal2004 and Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005), but the problematic features that C&P focus on are not confined to the Chomskyan mainstream, although they are probably more pronounced there than in other approaches.Footnote 2 The book may well help to usher in a new approach to research on UDs and to syntactic research more generally. It is potentially a landmark work. This, then, is the justification for another book dealing not with specific UDCs or with UDs in some not so well studied language but with UDs in a general way.

In the following pages, I will consider the issues in a general way first and then look in some detail at how C&P address them.

2. The movement approach to unbounded dependencies

Although it has been rejected by a variety of frameworks since the early 1980s, movement is still the favoured approach to UDs within the Chomskyan mainstream. By movement, I mean any mechanism which allows a constituent to occupy one position at one stage of a derivation and a different position at a later stage. This could be classical transformational rules, a general Move operation, or Internal Merge, i.e. Copy + Merge, followed by deletion. One anonymous referee objects to the suggestion that Internal Merge is a form of movement but without really explaining why. It has essentially the same effect as earlier mechanisms, and seems to face exactly the same problems. So when I refer to movement in the following pages, this includes Internal Merge.

Movement looks like an obvious approach if one just looks at the simplest examples. Consider, for example, (1):

Here, there is an extra clause-initial constituent, Kim, commonly called a filler, and a gap following on in the sense that a normally obligatory constituent is missing. Here and subsequently, I use an underscore to indicate a gap. The extra clause-initial constituent and the gap are mutually dependent in that neither can appear without the other:Footnote 3

Filler and gap can be indefinitely far apart. Thus, Kim in (1) could be followed by we know or I think we know or something even more complex. This is where the term unbounded dependency comes from.

Looking at an example like (1), it seems quite natural to suggest that the relation between filler and gap stems from the fact that the filler is moved to its superficial position from the gap position. Alternative approaches have long been advanced in frameworks like Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar, Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG), Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG), and Categorial Grammar,Footnote 4 but movement is still the most widely assumed approach. It is often discussed as if it were an unquestionable fact about syntax. Thus, in a widely used textbook, Radford (Reference Radford2009: 20) writes as follows:

If we compare the echo question He had said who would do what? in (18) with the corresponding non-echo question Who had he said would do what? in (19) we find that (19) involves two movement operations which are not found in (18).

But we only find this if we go looking for movement operations. What we find if we are not wedded to movement is certain similarities and differences between the two sentences in form and meaning, which must be accommodated by a satisfactory analysis. Movement might provide one way to do this, but it can be done without movement, as e.g. Ginzburg & Sag (Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000: Chapters 6, 7) show in some detail.Footnote 5

A fundamental fact about UDs is that they are very often not as simple as (1). For example, they may have no obvious filler or no obvious gap. It is worth looking at both these matters. Consider first the following:

Both these examples contain a relative clause. In (3a), the relative pronoun would traditionally be viewed as a filler, but if it is, there is no obvious filler in (3b). One might suggest that a man (or just man) is the filler in (3b), but then some rethinking is required for examples like (3a). Analyses of relative clauses in which they always contain a visible filler have been developed, notably in Kayne (Reference Kayne1994: Chapter 8), but it is by no means clear that such analyses are viable.Footnote 6 Whatever one thinks about relative clauses, it seems clear that there are UDCs with no visible filler. Consider the following:

Here, there is a gap following ignore, but there seems to be no filler. The gap is associated semantically with this problem, but this is a subject and not an extra clause-initial constituent, so not a normal filler. Rather similar is the following:

Here, there is gap following overlook, and again it is associated not with a normal filler but with a subject.

It has generally been accepted since Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Culicover, Wasow and Akmajian1977) that there are UDCs with no visible filler, but within mainstream syntax it has been assumed that such constructions contain an invisible filler, either one that is deleted (the approach of Chomsky Reference Chomsky, Culicover, Wasow and Akmajian1977) or one that is phonologically empty. This position is more or less inevitable. If UDs are the product of movement and there is no visible constituent that has been moved, there must be an invisible one. But it is only if one assumes movement that this invisible element is necessary. It is not necessary in non-movement approaches, as shown, for example, in Sag (Reference Sag2010: Sections 6.2–6.3), and other things being equal, approaches that do not require some invisible element must be preferable to approaches that do.Footnote 7

UDs with no obvious gap are not an important feature of English, but they are important in many other languages. Consider, for example, the following Welsh example:

Here, the English translation has a gap following the preposition with, but the Welsh example has not a gap but a pronoun following the preposition efo. Such resumptive pronouns (RPs) are an important feature of Welsh and many other languages. At one time it was widely assumed that there was no movement in UDs with an RP. However, in many languages they share major properties with UDs with a gap, and hence should be analysed in the same way. For mainstream syntax, this means in terms of movement.

But how can there be movement when there seems to be no gap from which something could have moved? One might suggest that movement somehow leaves behind not a gap but an RP. However, as McCloskey’s (Reference McCloskey, Epstein and Seeley2002: 192) notes, this approach cannot account for the fact that RPs universally look just like ordinary pronouns. The alternative is to propose that movement takes place not from the position where the RP appears but from a nearby position. Thus, for example, Willis (Reference Willis and Rouveret2011) proposes that Welsh examples like (6) involve movement from Spec PP. In the absence of independent evidence for a Spec PP position with relevant properties, this looks like just an ad hoc way to maintain a movement approach to UDs. Other analyses involving movement from a position near the RP are outlined in Aoun, Choueiri & Hornstein (Reference Aoun, Choueiri and Hornstein2001) and Boeckx (Reference Boeckx2003). It may be that there are more plausible ways of combining movement with an RP in some languages (see e.g. Van Urk Reference Van Urk2018). But the crucial point is that RPs pose no special problem for non-movement approaches to UDs. If there is no movement, there is no reason to think that there will always be gap.Footnote 8

While examples with no obvious filler or no obvious gap cast some doubt on movement approaches to UDs, arguably more important are examples with more than one gap. They were a central focus of the earliest work on a non-movement approach to UDs, Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981). Here is a typical example from C&P (numbers after examples refer to pages of C&P):

This contains three gaps, following praised, mourned, about, and three properties are ascribed to the Hungarian Revolution: it was praised and mourned, but nothing was done about it. Such examples have had a great deal of attention in the literature. Less discussed are examples like the following:

This does not ask what it was that Sam both ate and drank. Rather it asks: what did he drink? and what did he eat? Such examples pose a major problem for a movement approach to UDs, and they figure prominently in C&P’s discussion.

3. Island phenomena

Although filler and gap can be indefinitely far apart, there appear to be a variety of restrictions on UDs. These have generally been referred to as island phenomena, and they have been a major focus of research since Ross (Reference Ross1967). Here is a notable type of example:

Here, the gap is one conjunct of a coordinate structure, and the example is clearly unacceptable. A paraphrase with a gap in prepositional object position is fine:

It looks, then, as if some syntactic constraint must be responsible for the unacceptability of the example in (9).

It has generally been assumed that there are a variety of syntactic constraints in this area. For example, it was long assumed that extraction is only possible from one conjunct if there is extraction from all other conjuncts. (I will speak of extraction from now on although nothing is really extracted if there is no movement.) This idea was an important focus of Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981). But examples like the following from Goldsmith (Reference Goldsmith, Eilfort, Kroeber and Peterson1985), show that it is incorrect:

It has also been widely assumed that extraction is not possible from a subject. The following, from Huddleston, Pullum & Peterson (Reference Huddleston, Pullum and Peterson2002: 1093) shows that this is quite possible:

It has also been quite widely claimed that extraction is not possible from an adjunct, but an example like (12) from Hegarty (Reference Hegarty, Cheng and Demirdash1990) shows that this is not correct:

Probably no one thinks that syntax is irrelevant to island phenomena, and probably no one thinks they are entirely a matter of syntax. Hence, the question is not whether island phenomena are syntactic or not but how large or how small the role of syntax is. It seems that the mainstream view is still that syntax plays a very major role. One referee questions this, suggesting that ‘the “mainstream view” is that syntactic theories of locality have mainly walked away from island phenomena, leaving them to nonsyntactic or interface-based accounts’. However, another referee suggests that a syntactic approach faces ‘just a few exceptions’. There is clearly some mainstream work, which highlights the role of non-syntactic factors in Island phenomena, e.g. Boeckx (Reference Boeckx2012), but C&P present considerable evidence that a syntactic approach is still widely assumed. In contrast, as we will see, C&P argue that other factors play a dominant role. Building on earlier work such as Deane (Reference Deane1991) and Kluender (Reference Kluender, Goodluck and Rochemont1992, Reference Kluender, Culicover and McNally1998), they argue that most island phenomena are not the product of syntactic constraints and explore alternative explanations.Footnote 9

4. The underlying general approach

It is not hard to see that the problems just discussed stem in part from assumptions that have been very prominent in the study of syntax for many decades. One is the idea that there is no need when developing syntactic analyses to consider how they might fit into theories of language use. Another is the idea that acceptability is generally an unproblematic guide to grammaticality so that if a class of examples are unacceptable, it is generally reasonable to regard them as ungrammatical. Both ideas have been challenged, but they have been important features of most work on UDs and have a lot to do with its character.

Chomsky (Reference Chomsky1965) highlighted the distinction between linguistic knowledge and language use when he introduced the terms competence and performance. He identified the former as the main object of linguistic research, but commented that ‘a reasonable model of language use will incorporate, as a basic component, the generative grammar that expresses the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of the language’ (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1965: 11). This point seems to have had more influence outside the Chomskyan mainstream than within it. Thus, Bresnan (Reference Bresnan, Halle, Bresnan and Miller1978) argued against the 1970s version of transformational grammar and in favour of a precursor to Lexical Functional Grammar on the grounds that the latter fits more easily into a model of language use than the former. In similar vein, Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981: 155) argued for Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar on the grounds that it provides ‘the beginnings of an explanation for the obvious, but largely ignored, fact that humans process the utterances they hear very rapidly’. As Hans van de Koot has reminded me, this claim was challenged, notably by Barton, Berwick & Ristad Reference Barton, Berwick and Ristad1987, but the important point is that it took an outsider to highlight the issue. More recently, Sag & Wasow (Reference Sag and Wasow2011) argue for HPSG and against Minimalism on the basis of compatibility with models of linguistic performance. Naturally, there have been attempts to incorporate Minimalism into models of performance. but, as noted in Section 6, C&P show that they have been problematic in various ways.

All this is very relevant to the issue of movement. Movement does not seem to fit into either a model of production or a model of comprehension. On a movement analysis of (14), who originates as the object of about and is moved to its superficial position.

Neither hearers nor speakers do this. Hearers begin with the sentence they hear and among other things look for a gap with which the filler who can be associated. Speakers begin with who, and may be unsure momentarily how they are going to proceed, but normally follow with a sentence with an associated gap. This means that it is quite unclear what role movement could play in models of language use, and, as discussed in Section 6, major implementations of Minimalism do not assume movement. It seems unlikely that movement analyses would still be assumed decades after alternatives were first proposed if the need to incorporate a model of linguistic knowledge into models of language use had been at the centre of syntactic research.

The distinction between grammaticality and acceptability was also clearly spelled out by Chomsky (Reference Chomsky1965), who emphasized that sentences could be more or less unacceptable but grammatical, and explored some of the factors that can lead to grammatical sentences being unacceptable. There have always been researchers concerned with this matter, but it has had rather less impact than might have been expected. Over the decades, many syntacticians have been quick to assume that unacceptable examples are ungrammatical. Quite often, if a few examples of some kind sound odd, it has been assumed that all examples of that kind are ungrammatical. This seems to have changed somewhat over the last decade or so with the relation between acceptability and grammaticality a central concern in works such as Sprouse Schütze & Almeida (Reference Sprouse, Schütze and Almeida2013). But for long it received little attention within mainstream work. This is surely a major reason why the idea that island phenomena are mainly a product of syntactic constraints has been so widely assumed for so long.

There is a further feature of much work, at least in mainstream syntax, which is of some importance here. As a number of commentators have noted, there has been a tendency to focus on a narrow range of data. Culicover & Jackendoff (Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005: 535) remark that ‘much of the fine detail of traditional constructions has ceased to garner attention’. In similar vein, Sag (Reference Sag2010: 487) sees ‘a loss of both precision and descriptive coverage in the practice of transformational-generative grammar’. At one time, this was justified by a distinction between core constructions, which were seen as important, and peripheral constructions, which were thought to be of little interest. This distinction seems to have fallen by the wayside, but its effects seem to remain. It is of course true that not all data are equally important, and it is rational to concentrate on important facts and to ignore ones of less importance. But this can easily become a matter of concentrating on facts that are relatively straightforward for favoured analytic ideas while ignoring ones that are more difficult. A lot of important data has been presented in what can be viewed as mainstream literature and C&P draw on it extensively, but facts that have been noted in the literature have often not had the impact that they should have. To take a concrete example, Ross (Reference Ross1967: 242) cited the following as evidence that subjects are not always islands:

But it was generally assumed over the following decades that subjects are indeed islands, and examples like this were largely ignored until Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Freidin, Michaels, Otero and Zubizarreta2008). If one focuses on a narrow range of examples, one is likely to miss the problems that various types of example pose for both movement analyses and syntactic views of island phenomena.

All these matters figure prominently in C&P’s discussion, as will be seen in the following pages.

5. The nature of the book

C&P explore the issues highlighted above and others, notably acquisition, in seven main chapters and a brief conclusion. Their book might be compared with Ross’s (Reference Ross1967) dissertation. Both works have island phenomena as a central focus. Ross was hugely influential, and C&P could be at least as influential. But there are important differences. Ross’s approach is largely that described in the previous section (although he could not be said to have focused on a narrow range of data). In contrast, C&P see syntax as one component of a body of knowledge employed in language use and assume that syntactic analyses need to take this fully into account. They also recognise that acceptability is often not a good guide to grammaticality and take the view that careful experimentation may be necessary to establish the sources of acceptability judgements. They also seek to handle as broad a range of syntactic data as possible.

It is clear from the outset that this book is rather different from Ross’s dissertation. Processing issues are highlighted on page 2 when it is noted that hearers of UDs may have difficulty determining the position of the gap, and Section 1.4 is devoted to real-time processing and advocates a hybrid top–down and bottom–up parsing model. The complex nature of acceptability, especially in the area of island phenomena, is also highlighted early on, as are various non-canonical UDs, especially multiple gap examples. The examples in (7) and (8) above come from the first chapter, as does the following, which has no less than five gaps:

These matters are explored throughout the book, and one chapter (Chapter 6) is devoted to the results of experimental work. All this is quite different from Ross, and from most work on UDs of the last 50 years. It is perhaps worth adding that none of this should be seen as a criticism of Ross. There was clearly no possibility in 1967 of producing the kind of work that C&P have produced now. Ross’s dissertation was an extremely impressive piece of work. So is C&P’s book.

This is a complex book dealing with many different issues. I concentrate here on the central themes of the book, passing over some interesting but less important matters. The book may be quite demanding for readers who do not have all the types of expertise that C&P draw on, for example readers who are familiar with syntactic theory but not with the methods of experimental psychology, or vice versa. It is clear, however, that C&P have worked quite hard to make the various components of the book reasonably accessible, and if it requires an effort from some readers, it will be worth it.

In the following sections, I will look more closely at what C&P have to say about the nature of UDs, then I will consider the main themes of their discussion of islands, and finally I will look at their remarks about acquisition.

6. The nature of unbounded dependencies

C&P survey the various kinds of UDs in Chapter 2, and explore movement analyses in Chapter 4, and non-movement analyses in Chapter 5. As indicated above, they have two main types of argument against a movement approach to UDs and in favour of a non-movement approach. On the one hand, a movement approach is less able than a non-movement approach to handle the full range of UD possibilities. On the other, a movement approach seems much less suitable for incorporation into an account of language use than a non-movement account.

As emphasized earlier, many UDs are rather more challenging than the simple cases that get the most attention. Earlier work such as Levine & Sag (Reference Levine, Sag and Müller2003) and Borsley (Reference Borsley2012) has argued that such non-canonical UDs are problematic for a movement approach and straightforward for the non-movement approach, but C&P develop this point in much greater detail. They focus especially on multiple gap examples such as (7) and (8) above, repeated here as (17) and (18):

These are rather different from each other. (17) is what C&P call a convergent dependency, where multiple gaps are linked to a single filler and are co-referential. (18) is what they call a cumulative dependency, where multiple gaps are linked to a single filler but are not co-referential. As noted earlier, the former have had quite a lot of attention going back to Ross (Reference Ross1967) and they were a central concern of Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981). The latter have had a lot less attention. C&P make a number of points about this phenomenon. For example, they note that a cumulative interpretation can usually be forced with the aid of the adverb respectively, a topic previously discussed in Chaves (Reference Chaves2012):Footnote 10

Clearly, there is a challenge here for theories of syntax.

There has been work within the Minimalist Program on convergent dependencies, and also some consideration of cumulative dependencies, but C&P argue that it is unsatisfactory.

They look, for example, at the Sideward Movement approach of Nunes (Reference Nunes2001), in which the filler moves from one gap position to the other before eventually moving to its superficial position. They note that this has a problem with an example like the following from Goodall (Reference Goodall1987: 75), where the two gaps are associated with different cases and hence cannot be said to be copies.Footnote 11

They also note that cumulative UDs are problematic for this approach since the two gaps cannot be copies because they are not coindexed,

They also look at approaches involving multiple mothers, which they associate with Citko (Reference Citko2005) among others. They argue that examples in which one of the gaps is a conjunct such (21), are problematic:

They also argue that it excludes multiple UDCs, such as the following:

Cumulative UDs also seem problematic for this approach.

A more promising approach to cumulative UDs is the functional trace approach of Munn (Reference Munn1999). However, C&P note, following Gawron & Kehler (Reference Gawron, Kehler, Young and Zhou2003), that this has problems with examples involving conjoined VPs such as the following:

It seems, then, that multiple gap examples are a serious problem for movement approaches to UDs.

The alternative to movement which C&P advocate is an approach, originally proposed in Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981) and developed in detail in HPSG, in which the syntactic and semantic properties of signs include information about the gaps they contain.Footnote 12 Except at the bottom of a UD this gap information reflects the gap information associated with one or more daughters. For C&P, this is encoded by a feature GAP, whose value is a list of signs.Footnote 13 In simple cases, a sign and one of its daughters have the same value for GAP. Thus, we have trees of the following form, where any other daughters are [GAP <>] (<> being the empty list):

Consider, for example, (1) repeated here as (25):

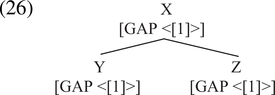

Among other things, this includes a VP rely on with a PP daughter on, and both are [GAP <NP>] because both contain an NP gap. In a more complex situation, a sign and more than one of its daughters have the same value for GAP. If there are just two daughters, this means trees of this form:

Example (7)/(17) includes a structure of this form. The VP praised and mourned has two VP daughters praised and and mourned, and all three VPs are [GAP <NP>]. This, then, is the form that convergent dependencies take. It would be difficult to allow structures like (24) without also allowing structures like (26). Thus, convergent dependencies are expected within this framework. Finally, a sign may combine information from the GAP values of two (or more) different daughters, giving trees such as the following, where there are just two daughters:

This is what is required for a cumulative dependency such as that in (8)/(18). This approach requires the constraints that capture the properties of various types of phrase to specify exactly how the GAP value of a phrase relates to the GAP values of its daughters. C&P show how this can be done on pages 178–180, using a precisely defined list-join relation. It is also necessary to provide analyses of the bottom of a dependency, where a gap or RP appears, and the top, which may or may not include a filler. C&P assume fairly standard HPSG ideas here. Thus, they have an approach which seems well able to handle the full range of UDs.Footnote 14

C&P discuss the way movement is problematic for models of language use at some length. They consider a number of explicit attempts to reconcile Minimalism with the facts of incremental processing, notably Chesi (Reference Chesi2007, Reference Chesi2015), Stabler (Reference Stabler2013), and Hunter (Reference Hunter and Sprouseforthcoming), and note that they end up with no movement and an approach to UDs that is reminiscent of that of Gazdar (Reference Gazdar1981).Footnote 15 They conclude (155) that ‘[t]here is no evidence for move operations in psycholinguistic or neurolinguistic research’ and that ‘all recent attempts to make the MP consistent with incremental sentence processing that we are aware of … abandon move altogether’. Unlike the movement approach, the approach developed by C&P is well suited to incorporation into models of language use. They emphasize that approaches like theirs ‘can be efficiently parsed, at scale, with basically the same algorithms that parse CFGs [Context-free Phrase Structure Grammars]’ (201). Thus, there seem to be two good reasons for preferring a non-movement approach to UDs to the traditional movement approach.Footnote 16

7. The nature of island phenomena

C&P focus on island phenomena in Chapters 3 and 5, and report on a series of experimental investigations in Chapter 6. They observe that

The major challenge that island phenomena pose to linguistic theory lies in precisely identifying whether a given phenomenon is due to syntax, semantics, pragmatics, processing, or some combination thereof. (51)

The dominant view has long been that island phenomena are largely a product of syntactic constraints. However, as noted earlier, various researchers have questioned this orthodoxy. Building on this work, C&P argue that most island phenomena are not a matter of syntax.

In Chapter 3, C&P show that there are exceptions to most syntactic constraints that have been proposed. Examples noted in Section 3 show that the Coordinate Structure Constraint, the Subject Constraint, and the Adjunct Constraint are untenable. Here are some further examples ((30) is from Pollard & Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1994: 191):

Much of C&P’s discussion of the issues involves drawing attention to data that has largely gone unnoticed.

One response to these problems is to try to develop a modified syntactic approach, which does not incorrectly rule out the sorts of examples just highlighted. This response will be particularly attractive if one thinks that there are just a few exceptions. C&P consider a number of proposals of this kind and find them unsatisfactory, essentially because there are more than just a few exceptions.

They look, for example, at Chomsky’s (Reference Chomsky, Freidin, Michaels, Otero and Zubizarreta2008) discussion of exceptions to the Subject Constraint. Chomsky develops an approach which predicts that extraction is possible from subjects which originate inside VP (because it can take place before the movement to subject position). A passive example like the following is unproblematic for this approach:

The examples in (12) and (29) above would also be unproblematic if their subjects could be analysed as originating inside VP. However, C&P point out that there are acceptable cases of extraction from a subject where such an analysis does not seem plausible, for example the following (141):Footnote 17

They also point out that this approach allows certain examples which are unacceptable.

C&P also consider the account of exceptions to Adjunct Constraint developed in Truswell (Reference Truswell2011), according to which violations are allowed when the main predicate and the modifier characterize the same event. They note that there are a variety of acceptable cases of extraction from an adjunct which do not have this property, for example the following (87):

(The example in (33a) comes from Hukari & Levine Reference Hukari and Levine1995, and (33b) is attributed by Truswell (Reference Truswell2011: 175 n. 1) to personal communication from Ivan A. Sag.) It seems, then, that this is not a very promising approach.

C&P explore these issues at some length, and show that there is strong evidence against an approach to islands which is primarily syntactic. However, they suggest that there is one important syntactic constraint, namely that a gap must be an argument, or more precisely a member of the ARG-ST list of a head. One point to note straightaway is that adverbial gaps in examples like the following are unproblematic for this approach:

Following Bouma, Malouf & Sag (Reference Bouma, Malouf and Sag2001), and other earlier work, C&P assume (33–36) that some adverbials are optional extra arguments. Hence such examples involve an argument gap and so are correctly allowed.

On the assumption that conjunctions are not heads with an ARG-ST list, this constraint accounts for the unacceptability of examples like (9) above, repeated here as (35).

C&P propose that this constraint is also responsible for the unacceptability of examples associated with the Left Branch Condition, such as (36).

It seems reasonable to assume that the gap in (36) is not an argument, but it is not obvious that this is true of the gaps in the following examples, where it looks rather like a subject argument:

This may well be an area where further thought is necessary.Footnote 18

C&P argue that a variety of non-syntactic factors are involved in island phenomena and provide a list on pages 58–59, but they focus especially on relevance in Grice’s sense (or that of Relevance Theory). They argue that

the only constraint that is common to all UDCs boils down to a general Gricean Relevance presupposition: speakers can felicitously draw attention to a referent by using a non-canonical construction such as a UDC only if the referent is sufficiently relevant to the main action that the utterance describes, i.e. if the referent is taken to be the center of current interest relative to the proposition in which it occurs. (203)

This is particularly relevant to when subjects are and are not islands. Subjects tend to be islands because they are commonly topics and hence their constituents cannot be ‘the center of current interest relative to the proposition in which it occurs’. But where a subject is not required to be a topic, it is not an island. As Abeillé et al. (Reference Abeillé, Hemforth, Winckel and Gibson2020) emphasize, this is generally the case in relative clauses, hence the acceptability of (12) above, repeated here as (38):

There are also cases where the subject of a wh-interrogative is not an island, as in the examples in (39):

Here, the extracted nominals are specific and cohere very well with the subject head nominal. Hence, they are unproblematic.

What is and is not relevant is also important for extraction from objects, where we have contrasts like the following (originally noted, as a referee has reminded me, by Bach & Horn Reference Bach and Horn1976):

As C&P note, these contrast ‘because the content of a book is relevant for understanding a book-reading scene, but not so much for understanding a book-dropping scene’ (207).

In Chapter 6, C&P turn to experimental evidence for their approach and report on five experiments into island phenomena, which build on earlier experimental work of Chaves and others. Three consider extraction from subjects, and two focus on adverbials. Their findings reinforce the conclusions reached in earlier discussion. Experiment 1 shows that extraction from subjects becomes more acceptable as a result of exposure, unlike clearly ungrammatical structures, and experiment 2 shows that the same is true of extraction from clausal subjects. Experiment 3 shows that the more important the extracted referent is for the proposition described by the utterance, the more acceptable extraction from a subject is. Experiment 4 shows that extractions from phrasal adverbials range from highly acceptable to highly unacceptable, and can improve dramatically with repeated exposure. Finally, experiment 5 suggests that a syntactic explanation is unlikely for the acceptability of extraction from tensed adverbial clauses. This chapter is an important feature of the book, distinguishing it from most work on UDs. It will not be surprising if much future work on UDs has a similar experimental component.

8. Acquisition

C&P might have addressed the main concerns of their book without considering acquisition, but whatever view of grammatical knowledge one subscribes to, it is natural to ask how it is acquired, and this is what C&P do in Chapter 7. Almost all theoretically informed research on the acquisition of syntax has taken mainstream Chomskyan syntax as its main point of reference.Footnote 19 This makes C&P’s discussion quite important.

Building on the discussion in Chapter 5, C&P propose that a speaker’s grammar is not a redundancy-free system of constructions of the kind that is standardly assumed within HPSG, but a system of chunks of grammatical structure of varying complexity and associated with specific frequencies. This conception can explain the fact that speakers process some structures more quickly than others which have the same status within a redundancy-free grammar and the fact that how quickly they process some structures may change over time. Crucially, in the present context, it allows grammatical knowledge to be gradually acquired from experience without need for any specifically linguistic innate assistance.

Particularly interesting is the discussion of polar interrogatives. C&P set out a formal account of their development (248–249). They also challenge the long-standing contention that they provide evidence for innate linguistic knowledge. It has been widely argued since the 1970s that only some form of innate knowledge could explain the fact that speakers produce sentences like (41a) and not non-sentences like (41b):

Within the general approach assumed by C&P, ‘[a]ll the child must learn, as far as syntax is concerned, is that a sentence-initial auxiliary is followed by its subject and its complement’ (246). Simple examples provide ample evidence for this. Examples like (41a) will be correctly produced once the learner has also mastered relative clauses.Footnote 20 There will be no possibility of something like (41b) being produced because it does not involve an auxiliary followed by its subject and its complement. The man who here is not a possible subject because it is not a well-formed NP, and is tall is not a possible complement of is because is does not allow a finite VP as its complement. A referee comments on this argument that ‘[i]t is far from obvious what “complement” means here and how the child can acquire this notion’. But ‘complement’ has just the same sense here as elsewhere, essentially a non-subject syntactic argument, and there are no special acquisition problems. If the notion is unproblematic in declaratives, it is unproblematic here. Thus, C&P’s discussion of this matter suggests that the idea that there is an argument in this area for some innate linguistic knowledge should finally be put to rest.Footnote 21

A number of other issues are discussed in this chapter, but it is quite short – just 16 pages. It seems to me, however, that the general approach outlined here is very promising. It is to be hoped that C&P or others will build on this approach. There is a great deal of work that could be done.

9. Final remarks

In the preceding pages I have sought to spell out the central themes of C&P’s book. However, there is much else that is of interest here. For example, they have an interesting discussion (97–100) of what they call the Complementizer Constraint, the unacceptability of a subject gap following a complementizer, exemplified by (42):

Building on the ideas of Kandybowicz (Reference Kandybowicz, Baumer, Montero and Scanlon2006, Reference Kandybowicz, Bunting, Desai, Peachey, Straughn and Tomková2009), they tentatively propose that this is due to conflicting prosodic phrasing requirements (100). Also of considerable interest is the discussion (108–110) of the relation of islands to ellipsis, which, they argue, provides evidence that ‘ellipsis resolution is a context-dependent anaphoric mechanism that does not require complex structure at the ellipsis site’ (108). Especially interesting in my view is the discussion of the relation of islands to the scope of quantifiers and in-situ interrogative words (110–119). C&P argue that the facts provide no evidence for covert movement, or, more theory neutrally, that there is no evidence that these phenomena involve the same mechanism as standard UDs.

Of course, none of this implies that there are no proposals here that can be questioned. I noted in Section 7 above that it is not obvious that the restriction that a gap must be an argument can account for the Left Branch Condition. It may not even account for the fact that a gap cannot be a conjunct. It is probably quite widely assumed within HPSG that conjunctions are markers combining with a sister which is not an argument. However, it has also been proposed, e.g. in Abeillé (Reference Abeillé and Müller2003), that conjunctions are weak heads, heads which derive most of their properties from their complement, so that a conjunction with a nominal complement has nominal properties, a conjunction with a verbal complement has verbal properties, and so on. On standard HPSG assumptions, the complement is an argument. Hence on this analysis, some other account is necessary for the fact that a gap cannot be conjunct.Footnote 22

It may be that there are no problems here. But it would be very surprising in a book of such breadth if there were not some proposals that ultimately turn out to be untenable. However, many of the detailed proposals are not that important. It is the central themes of the book that really matter, especially the critique of the movement approach to UDs and the syntactic approach to island phenomena, and the argument for an approach to syntax which takes full account of the fact that it is one component of a body of knowledge employed in language use and recognises that acceptability is often not a simple reflection of grammaticality. These all seem sound.

There are also some unresolved issues here. For example, C&P say the following about wh-islands:

Much more research is needed in order to pinpoint the combination of factors that give rise to English Wh-island effects and Superiority, but what seems clear is that purely syntactic accounts are unlikely to explain the full range of facts, given their gradience, sensitivity to context, and correlation with established models of sentence-processing difficulty. (97)

I also noted earlier that there is a great deal of work that could be done on acquisition, building on the approach outlined in Chapter 6. Again, this is not surprising in a book like this. C&P argue at length for a number of positions, but they are also setting out a research programme, and a research programme is essentially a collection of unresolved questions together with a strategy for resolving them.

The fact that C&P are both arguing for certain positions and setting out a research programme makes this a work of considerable importance. Again, it can be compared with Ross (Reference Ross1967), which obviously led to a great deal of research on island phenomena. This could do the same, but it will be research of a rather different kind with the relation between competence and performance and the complexity of acceptability judgements as central concerns. If the book has the impact that it deserves, syntactic research will come to look rather different. Put simply, there will be more work aiming to develop analyses that can be incorporated into models of language use and more work utilizing appropriate experiments to disentangle the sources of speakers’ judgements. It will be an important and very welcome change, perhaps even paradigm shift.