Introduction

When employees are reluctant to undertake organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), that is, extra-role work behavior that goes beyond their explicit job descriptions (Ocampo, Acedillo, Bacunador, Charity, Lagdameo, & Tupa, Reference Ocampo, Acedillo, Bacunador, Charity, Lagdameo and Tupa2018; Valeau & Paillé, Reference Valeau and Paillé2019), it generates important concerns for organizations. Such behavior can take different forms: Sustained efforts might add directly to organizational performance, or incremental efforts could help the organization reduce its regular operating costs, for example (Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, Reference Organ, Podsakoff and MacKenzie2006). But irrespective of their nature, voluntary work activities improve the organization's internal functioning (Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011), and they also can benefit the employees who engage in them, such as by generating a sense of personal fulfillment (Lemoine, Parsons, & Kansara, Reference Lemoine, Parsons and Kansara2015). But if employees experience personal challenges, including sleep deprivation due to an inability to fall asleep or maintain a steady amount of sleep (Kucharczyk, Morgan, & Hall, Reference Kucharczyk, Morgan and Hall2012), they may be less likely to exhibit such productive work behaviors and instead could display poor attentiveness (Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006) or diminished creative behavior (De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021).

Such considerations are timely, according to evidence that many workers suffer from sleep difficulties (Garcia, Bordia, Restubog, & Caines, Reference Garcia, Bordia, Restubog and Caines2018). Therefore, we explicitly seek to determine whether and how employees' experience of work-induced sleep deprivation, which implies that their sleep problems stem from work-related causes, might diminish their OCB, as well as address the potential harms of this behavioral response (Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff, & Blume, Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009). Organizations that rely on their employees' OCB need a clear understanding of how personal hardships can escalate to affect people's work efforts; we take a unique perspective by identifying and detailing the connection between insomnia caused by work and decreased OCB. To the best of our knowledge, these two negative phenomena have not been investigated together, despite their prevalence in contemporary workplaces. To provide novel insights into why and when work-induced sleep deprivation might curtail employees' OCB, we also consider two unexplored, relevant factors: employees' dehumanization of organizational leaders (Kilroy, Flood, Bosak, & Chenevert, Reference Kilroy, Flood, Bosak and Chenevert2016) and the level of job formalization imposed by the firm (De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013).

These considerations reflect the tenets of conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). First, as a resource-depleting force, work-induced sleep deprivation might motivate sleep-deprived employees to find solutions that enable them to minimize the threats to their self-esteem resources or sense of self-worth (Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall, & Alarcon, Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010). For example, they might seek an external cause of their sleep deprivation and land on organizational leaders as scapegoats. In this process, employees might detach psychologically from their organizational leaders, treating them like impersonal objects (Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short, & Wang, Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000), which we refer to as dehumanization or depersonalization (Gardner, Reference Gardner1987; Zopiatis & Constanti, Reference Zopiatis and Constanti2010). In so doing, they also might be more likely to decrease their OCB.

Second, and as also predicted by COR theory, we propose that these escalating effects might be catalyzed if employees are subject to substantial job formalization, such that they believe they have little choice other than to comply with strict organizational procedures and policies to complete their job tasks (Schminke, Ambrose, & Cropanzano, Reference Schminke, Ambrose and Cropanzano2000). Formal structures arguably can spur efficiency, commitment, and loyalty (Adler & Borys, Reference Adler and Borys1996; Lee & Antonakis, Reference Lee and Antonakis2014), but if employees already are exhausted and upset because their work has deprived them of sleep, they might experience formalization as intrusive and disruptive to their professional functioning. As previous research indicates, job formalization can exert various counterproductive influences, such as job stress (Nasurdin, Ramayah, & Beng, Reference Nasurdin, Ramayah and Beng2006), burnout (Bilal & Ahmed, Reference Bilal and Ahmed2017), alienation (Chiaburu, Thundiyil, & Wang, Reference Chiaburu, Thundiyil and Wang2014), and diminished trust in management (Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006).

Contributions

By taking this novel perspective, we offer several contributions and insights, extending prior research on insomnia. First, most organizational studies in this domain focus on employees' experience of sleep problems in general, without assigning them to work-related causes (Barnes, Miller, & Bostock, Reference Barnes, Miller and Bostock2017; De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021). We add new nuance, by examining how employees respond to persistent sleep difficulties caused by their jobs. These causes may vary – such as disruptive organizational changes (Rafferty & Jimmieson, Reference Rafferty and Jimmieson2017) or discriminatory workplace treatment (Ragins, Ehrhardt, Lyness, Murphy, & Capman, Reference Ragins, Ehrhardt, Lyness, Murphy and Capman2017), to name just two – but rather than measure them explicitly, we establish work-induced sleep deprivation as an instrumental construct to reveal how employees cope with precarious situations that threaten their ability to do their jobs (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). As we theorize, persistent sleep deprivation caused by work might lead employees to become complacent in their work efforts, as a means to avoid self-damaging thoughts about their own professional functioning (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010).

Second, we reveal an unexplored mechanism by which work-induced sleep deprivation prompts work-related complacency (which we measure as lower OCB): Employees become indifferent toward organizational authorities (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000). Previous studies have outlined how employees' dehumanization of others can connect resource-depleting conditions that affect them – such as ethical-laden conflict (McAndrew, Schiffman, & Leske, Reference McAndrew, Schiffman and Leske2019), role conflict (Kang & Jang, Reference Kang and Jang2019), or emotional labor (Lee, Ok, Lee, & Lee, Reference Lee, Ok, Lee and Lee2018) – to negative work consequences. Our investigation of the dehumanization of organizational leaders is theoretically interesting, because it details how sleep-deprived employees might protect their sense of self-worth by blaming their personal difficulties (i.e., sleep deprivation) on these key internal stakeholders who run the company (Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006), a process that also leads to their diminished OCB.Footnote 1 We thus identify a potential downward spiral with multiple threats to employees. Their personal well-being is undermined by their lack of sleep, which they suffer due to work (Wagner, Barnes, & Scott, Reference Wagner, Barnes and Scott2014), and they respond by dehumanizing their leaders and exhibiting indifference or complacency at work, two reactions that are unlikely to be well-received by the leaders (Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011) and thus might cause even more personal hardships for employees.

Third, we go into more detail by specifying how this negative spiral may increase in strength if sleep-deprived employees also feel constrained by formalized work environments that prevent them from performing their work tasks flexibly (Schminke, Ambrose, & Cropanzano, Reference Schminke, Ambrose and Cropanzano2000). If employees believe they must adhere strictly to formal guidelines, they likely suffer self-depreciating thoughts about their work functioning, particularly if they already suffer from work-induced sleep deprivation, and those combined effects may have especially negative consequences for their view of organizational leaders and OCB. By investigating this invigorating role of job formalization, we add to findings that suggest it moderates the links of other factors and outcomes, such as employees' goal orientations (Hirst, Van Knippenberg, Chen, & Sacramento, Reference Hirst, Van Knippenberg, Chen and Sacramento2011), self-direction (Nathan, Prajogo, & Cooper, Reference Nathan, Prajogo and Cooper2017), and reliance on knowledge-sharing routines (De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013). From a theoretical angle, our findings reveal that organizations need to realize how employees' perceptions of red tape may augment their frustrations linked to work-induced sleep problems and thereby fuel a sense that organizational leaders deserve to be dehumanized (Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006) and that diminished extra-role efforts are justified, with harmful implications for organizational effectiveness (Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011).

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Opportunities and challenges of OCB

Organizational scholars emphasize the benefits for organizations if their employee bases engage in OCB. The extent to which employees play a ‘good soldier’ role (Organ, Reference Organ1988) can determine both the organization's competitive advantage and their own work-related outcomes (Bachrach, Powell, Collins, & Richey, Reference Bachrach, Powell, Collins and Richey2006; Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011). For example, extra-role work activities might grant employees personal satisfaction (Lee, Kim, & Kim, Reference Lee, Kim and Kim2013) and enhance their standing among other members, including organizational leaders (Korsgaard, Meglino, Lester, & Jeong, Reference Korsgaard, Meglino, Lester and Jeong2010; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009). Yet voluntary behaviors can be challenging, in that they usurp significant energy and may keep employees from meeting their regular job obligations (Bergeron, Reference Bergeron2007; Koopman, Lanaj, & Scott, Reference Koopman, Lanaj and Scott2016). In addition, colleagues may regard extra-role activities skeptically, as unnecessary or insincere ingratiation or as threats to their own standing (Klotz, He, Yam, Bolino, Wei, & Houston, Reference Klotz, He, Yam, Bolino, Wei and Houston2018). Considering the coexistence of both advantages and difficulties, it is critical to clarify how employees decide whether they will engage in OCB and which pertinent factors inform their choice (Arain, Bhatti, Ashraf, & Fang, Reference Arain, Bhatti, Ashraf and Fang2020; Mackey, Bishoff, Daniels, Hochwarter, & Ferris, Reference Mackey, Bishoff, Daniels, Hochwarter and Ferris2019).

Various factors might leave employees reluctant to undertake voluntary work efforts. Some studies highlight the inhibitive role of organizational factors, such as abusive supervision (Ahmad, Athar, Azam, Hamstra, & Hanif, Reference Ahmad, Athar, Azam, Hamstra and Hanif2019), career dissatisfaction (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2021), self-centered or political decision-making (Khan, Khan, & Summan, Reference Khan, Khan and Summan2019), or job stress (Syed, Naseer, & Bouckenooghe, Reference Syed, Naseer and Bouckenooghe2021). Other studies point to personal factors, such as selfish monetary goals (Tang, Sutarso, Wu Davis, Dolinski, Ibrahim, & Wagner, Reference Tang, Sutarso, Wu Davis, Dolinski, Ibrahim and Wagner2008), a lack of pro-social motives (Choi & Moon, Reference Choi and Moon2016), a reactive instead of proactive personality (Li, Liang, & Crant, Reference Li, Liang and Crant2010), or limited confidence in one's own skills (Waheed, Imdad, Ahmed, Ghulam, Sayed, & Umrani, Reference Waheed, Imdad, Ahmed, Ghulam, Sayed and Umrani2020). Noting evidence from prior research that persistent sleep shortages can diminish employees' propensities to develop new ideas for organizational improvement (De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021) or generate job dissatisfaction (Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006), we seek to identify its potential influence on OCB, using a more nuanced approach that differentiates sleep problems that originate from work, rather than challenging life situations in general. That is, we investigate how employees respond to work-induced sleep deprivation by addressing how (1) the link between work-induced sleep deprivation and OCB might be mediated by dehumanization of organizational leaders and (2) this process might be moderated by perceptions of job formalization.

COR theory

The arguments for these mediating and moderating effects are grounded in COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). According to this theory, employees' work-related behaviors reflect their motivation to protect their current resource bases and avoid additional resource losses when they encounter resource-draining conditions. This argument establishes two critical premises (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). First, the threat of resource depletion, caused by adverse experiences, steers employees toward actions that enable them to counter the depletion and cope with the experienced hardships (Westman, Hobfoll, Chen, Davidson, & Laski, Reference Westman, Hobfoll, Chen, Davidson and Laski2004). Second, certain contextual factors can trigger this process, particularly those that make it more likely that the experienced hardships harm the quality of employees' professional functioning (De Clercq, Haq, & Azeem, Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2020).

We take care to note that COR theory conceptualizes ‘resources’ quite broadly, such that they entail any ‘objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are valued in their own right, or that are valued because they act as conduits to the achievement or protection of valued resources’ (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001: 339). But a particularly relevant resource that employees vigorously seek to protect, according to Hobfoll (Reference Hobfoll2001) and subsequent investigations (e.g., Bedi, Reference Bedi2021; Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain, & Chênevert, Reference Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain and Chênevert2017), is their self-esteem. If employees experience work-induced sleep deprivation, it could threaten this self-worth resource, because that experience implies their employer cares little about their personal well-being (Wagner, Barnes, & Scott, Reference Wagner, Barnes and Scott2014). If sleep problems due to work are persistent, employees might develop a need to assign responsibility to others for their damaged self-esteem, such as the people in charge of the company (De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021; Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006). In an encompassing review of COR theory, Hobfoll et al. (Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018: 104) similarly explain that employees who suffer resource-draining situations tend to ‘enter a defensive mode to preserve the self that is often aggressive and may become irrational.’

Consistent with the aforementioned first COR premise, we accordingly propose that employees' dehumanization of organizational leaders and subsequent diminished voluntary work activities represent predictable, likely responses to work-induced sleep deprivation, reflecting their natural desire to safeguard their remaining resource reservoirs (i.e., self-esteem) (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010). As coping tactics, such responses enable them to express their disappointment with the situation, in which their work harms their sleep quality (Barnes, Reference Barnes2012; Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). Furthermore, in line with the second COR premise, the probability that sleep-deprived employees turn to these coping tactics should be higher if they face other job challenges that make the negative responses seem even more justified (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). We propose specifically that employees are more likely to express frustrations about work-induced sleep deprivation by dehumanizing organizational leaders when they feel constrained by formalized work processes that allow for ‘little flexibility … in determining how a decision is made or what outcomes are due in a given situation’ (Schminke, Ambrose, & Cropanzano, Reference Schminke, Ambrose and Cropanzano2000: 296). This additional threat to employees' sense of self-worth signals that organizational leaders want to constrain their actions or dampen their creativity (Bilal, Ahmad, & Majid, Reference Bilal, Ahmad and Majid2018; Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006). To deal with it, sleep-deprived employees might react strongly, by dehumanizing the organizational leaders (Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen, & Griffeth, Reference Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen and Griffeth2013). That is, a restrictive job environment reinforces the hardships created by work-induced insomnia, with detrimental consequences for the effort and care employees are willing to exhibit toward their employing organization and its leaders (De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021).

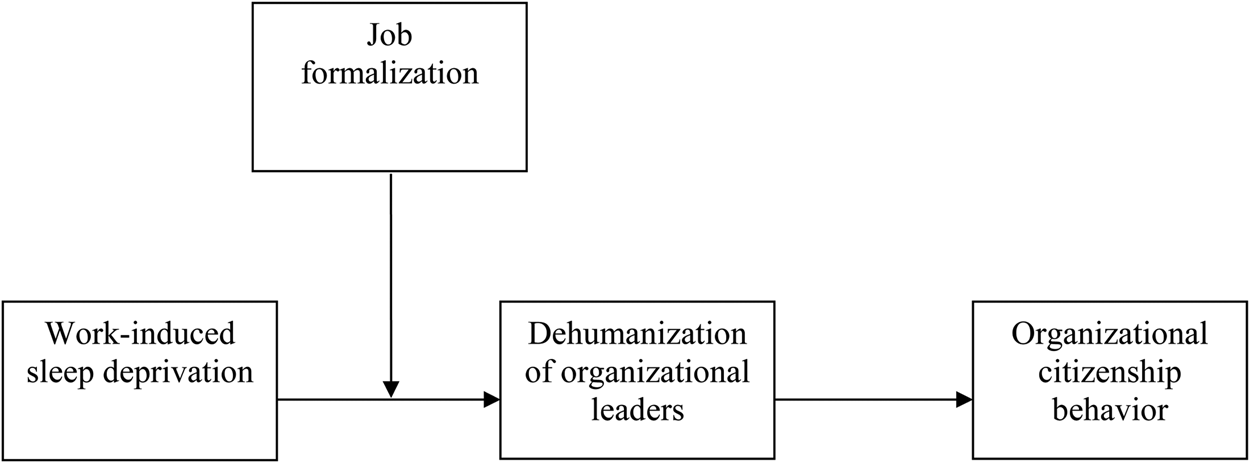

The proposed conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. Persistent sleep shortages due to work make it more likely that employees treat organizational leaders as impersonal objects, which diminishes their propensity to do more than is required by their explicit job duties. This dehumanization therefore functions as a critical conduit through which work-induced deprivation escalates into lower OCB. Job formalization also serves as a catalyst; the escalation of work-induced deprivation into diminished work-related voluntarism through dehumanization is more salient among employees who believe their jobs require strict adherence to formal work procedures.

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

Hypotheses

Mediating role of dehumanization of organizational leaders

We predict a positive relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and the dehumanization of organizational leaders. Employees who sense that their organization compromises their sleep quality may interpret the situation as a signal that its leaders do not find it necessary to ensure their personal well-being (Barnes, Reference Barnes2012; Kageyama, Nishikido, Kobayashi, Kurokawa, Kaneko, & Kabuto, Reference Kageyama, Nishikido, Kobayashi, Kurokawa, Kaneko and Kabuto1998). This aversive belief may induce employees to vent their irritation, by psychologically detaching from those leaders, consistent with COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). The frustration that employees likely experience if their work keeps them from a good night's sleep may undermine their sense of self-worth to such an extent that they blame organizational leaders and come to believe it is legitimate to treat those leaders like impersonal objects (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010; Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006). Through these responses, employees can cope better with their work-induced suffering and release their frustration with how their employer treats them (Toker, Laurence, & Fried, Reference Toker, Laurence and Fried2015; Winstanley & Whittington, Reference Winstanley and Whittington2002). They also reduce the likelihood of further resource losses (i.e., tarnished self-esteem), because employees feel as if they have held organizational leaders accountable and punished them with their indifference (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). In short, depersonalization gives employees a way to deal with their work-induced sleep deprivation, by expressing irritation that their leaders are causing the problem (De Clercq & Pereira, Reference De Clercq and Pereira2021). We accordingly hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: There is a positive relationship between employees' work-induced sleep deprivation and their dehumanization of organizational leaders.

The logic of COR theory further suggests that employees who dehumanize organizational leaders may avoid voluntary work behaviors, a reaction that likely has negative consequences for these leaders (Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011). That is, they regard diminished OCB as a justified behavioral response that can boost their sense of self-worth, because it aligns with their convictions that their organization and its leaders do not deserve their work-related dedication (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). Employees' efforts to dehumanize organizational leaders similarly might decrease their OCB, because this response makes them feel better about their choice to treat their leaders as impersonal objects (Altunoglu & Sarpkaya, Reference Altunoglu and Sarpkaya2012; Densten, Reference Densten2001). If employees can justify their dehumanization of organizational leaders, they also might halt their OCB, because doing so generates resource gains in the form of a sense of personal fulfillment (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000). They want nothing to do with organizational leaders, and they match this preference with their work-related complacency (Arabaci, Reference Arabaci2010; Dunford, Shipp, Boss, Angermeier, & Boss, Reference Dunford, Shipp, Boss, Angermeier and Boss2012). Conversely, employees who regard organizational leaders as human beings who deserve dedication likely devote significant energy to extra-role work activities that promise to add value to the organization and benefit its senior leadership (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009). Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: There is a negative relationship between employees' dehumanization of organizational leaders and their organizational citizenship behavior.

These arguments imply a mediating role of the dehumanization of organizational leaders. Insomnia caused by work reduces employees' propensities to be ‘good soldiers’ and do more than is listed in their job description because they psychologically detach from organizational leadership. If they sense that their organization is the cause of their sleep problems, employees likely refuse to allocate their valuable energy resources to voluntary work activities, reflecting their desire to diminish their self-depreciating thoughts about how they are being treated and their associated propensities to release their frustrations on leaders (De Clercq, Fatima, & Jahanzeb, Reference De Clercq, Fatima and Jahanzeb2021; Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006). The escalation of work-induced sleep deprivation into reduced OCB thus materializes through the indifference that employees exhibit toward the people who run the company. As noted, prior research reveals a similar mediating role of employees' depersonalization when it connects other resource-draining conditions – such as job roles, ethical issues, and emotional labor (Kang & Jang, Reference Kang and Jang2019; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ok, Lee and Lee2018; McAndrew, Schiffman, & Leske, Reference McAndrew, Schiffman and Leske2019) – with less positive work outcomes. We add to this research stream by proposing:

Hypothesis 3: Employees' dehumanization of organizational leaders mediates the relationship between their work-induced sleep deprivation and organizational citizenship behavior.

Moderating role of job formalization

Job formalization reflects the extent to which an organization's functioning is marked by strict organizational policies and guidelines (De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013). We propose an invigorating effect of employees' perceptions of such job formalization on the positive relationship between their work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders. Most formal procedures likely reflect organizations' efforts to enhance the efficiency of their internal operations, and when they are explained clearly and in advance, they enable employees to adjust their work practices and comply (Adler & Borys, Reference Adler and Borys1996). But this rosy view of job formalization coexists with some adverse effects, which may be especially prominent for employees who already feel sleep deprived due to their work (Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006). As extant research shows, organizational red tape can deplete employees' resources (Bilal & Ahmed, Reference Bilal and Ahmed2017; Nasurdin, Ramayah, & Beng, Reference Nasurdin, Ramayah and Beng2006) and alienate them from organizational leaders (Chiaburu, Thundiyil, & Wang, Reference Chiaburu, Thundiyil and Wang2014). In studying the constraining influences of job formalization, Huang and Van de Vliert (Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006: 221) also argue that ‘highly formalized units are less conducive to fostering trustworthy behaviors such as open employee management communication, causing employees to have lower levels of trust in management.’

In developing responses to resource-depleting circumstances, according to COR theory, employees consider the gravity of the depletion (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Arguably then, if employees feel restricted in their freedom to do their jobs – because they sense they are expected to adhere strictly to written procedures and guidelines – they may perceive a powerful threat to their sense of self-worth, and especially so if they already suffer from sleep problems due to work (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010). For these employees, work-induced sleep difficulties represent forceful detriments in terms of their self-esteem, because their job formalization prevents them from tackling the source of the problem flexibly or creatively (Kaufmann, Borry, & DeHart-Davis, Reference Kaufmann, Borry and DeHart-Davis2019; Nathan, Prajogo, & Cooper, Reference Nathan, Prajogo and Cooper2017). In this situation, the probability that they seek to protect their self-image by blaming organizational leaders and treating them as impersonal objects likely increases (Arabaci, Reference Arabaci2010; Kilroy et al., Reference Kilroy, Flood, Bosak and Chenevert2016). The constraining work environment reaffirms the sense of sleep-deprived employees that their organization and its leaders do not care about their well-being (Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006; Lapidus, Roberts, & Chonko, Reference Lapidus, Roberts and Chonko1997). Therefore,

Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between employees' work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders is moderated by their experience of job formalization, such that this positive relationship is stronger at higher levels of job formalization.

These arguments, combined with our predictions about the mediating role of dehumanization of organizational leaders, imply a moderated mediation dynamic (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007). A formalized work environment serves as a contingency of the indirect negative relationship between employees' work-induced sleep deprivation and their OCB, through their indifference to organizational authorities (Densten, Reference Densten2001; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Ok, Lee and Lee2018). In other words, if job tasks are highly formalized, employees' psychological detachment from organizational leaders more effectively explains how insomnia, due to work, escalates into diminished voluntarism at work. Job formalization thus serves as a catalyst of a possible negative spiral, in which frustrations about sleepless nights make the situation even worse if employees become unwilling to take on voluntary activities beyond their explicit job duties.

Hypothesis 5: The indirect negative relationship between employees' work-induced sleep deprivation and organizational citizenship behavior, through enhanced dehumanization of organizational leaders, is moderated by their experience of job formalization, such that this indirect relationship is stronger at higher levels of job formalization.

Research method

Data collection

To test the research hypotheses, we collected survey data from employees who work in a large organization that employs about 700 people and operates in the oil distribution sector in Angola. This focus on one organization reduces the potential influence of relevant but unobserved differences in various organizations' competitive markets or their unique internal functioning on employees' propensity to spend time on activities beyond their prescribed job duties (Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, Reference Organ, Podsakoff and MacKenzie2006). Because the oil sector in Angola is critical to the country's economy, it is subject to significant scrutiny from powerful external stakeholders (Ovadia, Reference Ovadia2016). Yet it also is marked by high levels of unemployment, due to the volatility of oil prices and the country's generally adverse economic climate (Oliveira, Reference Oliveira2015). Accordingly, many employees in this sector likely encounter work-induced hardships, which may spill over into the private sphere in the form of persistent insomnia (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Bordia, Restubog and Caines2018). The empirical setting thus is relevant for investigating pertinent issues of why and when employees' frustration about their poor sleep quality, caused by work, could steer them away from voluntary work efforts.

From a more general perspective, the Angolan context enables us to address calls for more investigations of how and when employees in African-based organizations allocate their energy resources to extra-role work activities (e.g., Mekpor & Dartey-Baah, Reference Mekpor and Dartey-Baah2020; Onyishi, Amaeshi, Ugwu, & Enwereuzor, Reference Onyishi, Amaeshi, Ugwu and Enwereuzor2020). Its cultural profile, featuring high levels of uncertainty avoidance and collectivism, makes it a particularly interesting setting too. Persistent sleep shortages tend to cause employees to feel uncertain about their professional growth and development (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Bordia, Restubog and Caines2018), and the uncertainty avoidance that already marks Angola's culture may reinforce the chances that employees develop self-depreciating thoughts about work-induced insomnia and respond to it in negative ways (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010). Yet high levels of collectivism might subdue the translation of such sleep deprivation into reduced work-induced voluntarism, through dehumanization of organizational leaders, because employees feel responsible for maintaining the collective well-being of their organization (Hui, Lee, & Wang, Reference Hui, Lee and Wang2015). Considering these opposing forces, Angola provides a compelling setting for this study, with great practical relevance for any organization that operates in country contexts that share similar cultural characteristics.

After the organization's senior management endorsed this study, we requested the participation of 250 employees, selected on a random basis from a list of employees provided by the organization's human resources department. Various measures were taken to protect participants' rights: An invitation statement that accompanied the survey emphasized the complete confidentiality of their responses, affirmed that the organization would not be informed about who participated, and noted that only composite results and overall data patterns would be included in any research output. We reassured the respondents that they could not give ‘good or bad’ answers and that their responses likely would vary from the answers offered by their peers. These clarifications diminish the risk of acquiescence or social desirability biases (Spector, Reference Spector2006). We received 207 completed responses, for a response rate of 83%. Among the respondents, 39% were women; they had worked in their current jobs for an average of 10 years; 14% had supervisory responsibilities; and 46% worked in an operational function, 26% in a commercial function, and 28% in an administrative function.

Measures

The measurement items for the four focal constructs came from previous studies and used 7-point Likert anchors that ranged between 1 (‘strongly disagree’) and 7 (‘strongly agree’).

Work-induced sleep deprivation

To assess the extent to which employees suffer from sleep problems due to work, we applied a four-item scale of sleep deprivation (Cole, Cai, Martin, Findling, Youngstrom, & Garber, Reference Cole, Cai, Martin, Findling, Youngstrom, Garber and Forehand2011). In light of our theoretical focus on work-induced insomnia, we adapted the original scale wording slightly. For example, respondents answered whether ‘It takes me a long time to fall asleep because of work’ and ‘I often wake up in the middle of the night because of work’ (Cronbach's α = .76).Footnote 2

Dehumanization of organizational leaders

We measured employees' dehumanization of organizational leaders with an adapted five-item scale of depersonalization toward coworkers (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000). Two sample items were ‘I give organizational leaders the ‘silent treatment’’ and ‘I do not give organizational leaders required information’ (Cronbach's α = .89).

Organizational citizenship behavior

We captured the extent to which employees undertake voluntary work efforts with a four-item OCB scale (De Cremer, Mayer, van Dijke, Schouten, & Bardes, Reference De Cremer, Mayer, van Dijke, Schouten and Bardes2009). For example, employees rated whether ‘I undertake voluntary action to protect the organization from potential problems’ and ‘If necessary, I am prepared to work overtime’ (Cronbach's α = .78). Our reliance on this self-rated measure is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Asplund, Reference Asplund2020; Johnson & Lake, Reference Johnson and Lake2019; Song, Kim, & Lee, Reference Song, Kim and Lee2019) and with the argument that other raters (e.g., peers, supervisors) have only a partial view of the range of voluntary activities that employees undertake during the course of their work (Chan, Reference Chan, Lance and Vandenberg2009; Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, Reference Organ, Podsakoff and MacKenzie2006). A meta-analysis also reveals only very small differences between self- and other-rated measures of OCB (Carpenter, Berry, & Houston, Reference Carpenter, Berry and Houston2014).

Job formalization

We measured employees' beliefs about whether they have to adhere to written procedures and policies for their individual job tasks with a five-item scale of organizational formalization (De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013). The participants indicated their agreement with statements such as, ‘I feel that there are written procedures and guidelines for most aspects of my job’ and ‘I feel that I have to follow established, formal policies to do my job’ (Cronbach's α = .75).

Control variables

We controlled for employees' gender (0 = male, 1 = female), job tenure (in years), job level (0 = no supervisory responsibilities, 1 = supervisory responsibilities), and job function (operational, commercial, or administrative, with the latter category serving as the base case). Women tend to be more eager than men to assist their employing organization with extra-role behaviors (Belansky & Boggiano, Reference Belansky and Boggiano1994). Employees who have longer job tenures or occupy higher positions also may have more ability to take on extra tasks in addition to their regular job duties (Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2013). Finally, the nature of their jobs may influence the perceived feasibility or desirability of going beyond the call of duty (Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, Reference Organ, Podsakoff and MacKenzie2006).

Construct validity

We used the statistical software AMOS 26 to perform a confirmatory factor analysis on a four-factor measurement model, which indicated an excellent fit: χ2(113) = 180.79, confirmatory fit index = .95, Tucker–Lewis index = .93, incremental fit index = .95, and root mean squared error of approximation = .05. All the items showed strong factor loadings on their respective constructs (p < .001), which confirmed the presence of convergent validity. In addition, evidence for discriminant validity was apparent in the fit of the six models with constrained construct pairs, in which correlations between two constructs were forced to equal 1, which was significantly worse than the fit of the corresponding unconstrained models in which correlations between the constructs were free to vary (Δχ2[1] > 3.84, p < .05).

Common source bias

With two diagnostic tests, we assessed whether reliance on a common respondent was a concern. First, Harman's one-factor test, conducted with an exploratory factor analysis in SPSS 26, indicated that the four focal constructs – work-induced sleep deprivation, dehumanization of organizational leaders, OCB, and job formalization – were responsible for only 29% of the total data variance. Second, a confirmatory factor analysis conducted in AMOS 26 affirmed that the fit of the four-factor measurement model was superior to that of the single-factor model in which all items loaded on one construct (χ2[6] = 538.73, p < .001). From a conceptual perspective, the chances of common source bias are significantly diminished if a theoretical framework includes moderation, because participants generally cannot guess the research hypotheses and adapt their responses accordingly (Simons & Peterson, Reference Simons and Peterson2000). Overall then, common source bias is unlikely to affect our findings.

Results

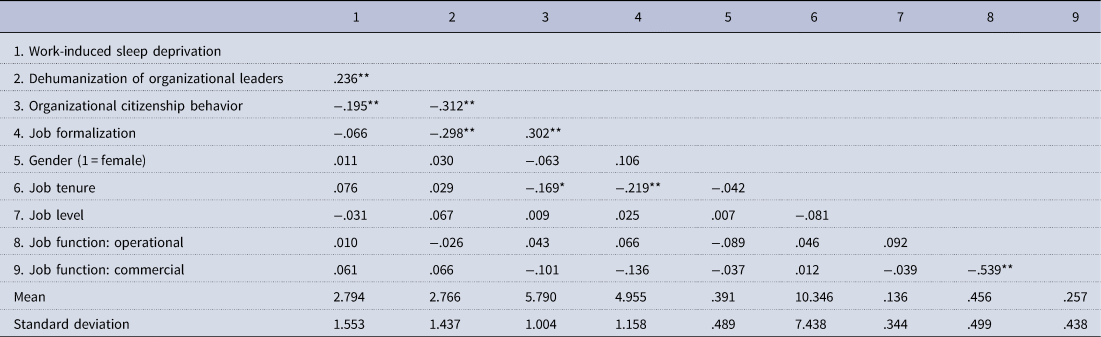

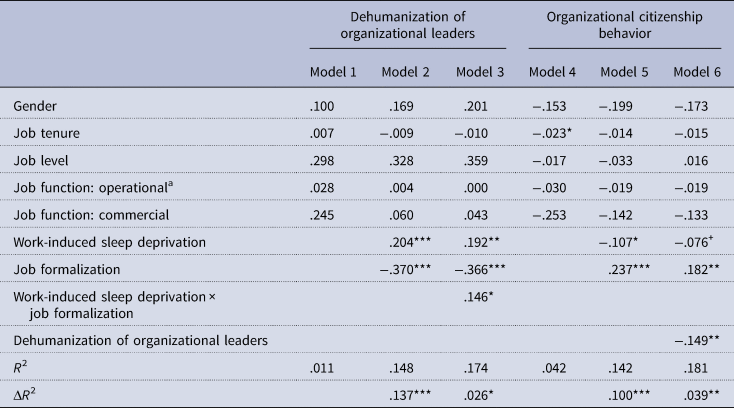

Table 1 provides the correlations and descriptive statistics, and Table 2 contains the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. Models 1–3 predict the dehumanization of organizational leaders, and Models 4–6 predict OCB. In each model, the values of the variance inflation factors were lower than the conservative cut-off value of 5, so we are not concerned about multicollinearity.

Table 1. Correlation table and descriptive statistics

Notes: N = 207.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

Table 2. Regression results

Notes: N = 207 (unstandardized regression coefficients).

a Administrative job function serves as the base case.

+ p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

In support of our argument in Hypothesis 1 that employees who suffer insomnia due to work treat organizational authorities as impersonal objects, we found a positive relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders in Model 2 (β = .204, p < .001). In turn, psychological detachment from their leaders decreased the likelihood that employees undertook voluntary work activities, as revealed by the negative relationship between dehumanization of organizational leaders and OCB in Model 6 (β = −.149, p < .01).

To assess the mediating role of dehumanization of organizational leaders, we first adopted a traditional approach, as recommended by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986). The findings presented in the previous paragraph established the significant relationships between the independent variable and mediator and between the mediator and dependent variable. When we accounted for the effect of dehumanization of organizational leaders, the negative relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and OCB in Model 5 (β = −.107, p < .05) grew weaker (β = −.076, p < .10, Model 6), signaling partial mediation. To corroborate the presence of this mediation, we also applied the Process macro and its bootstrapping procedure (Hayes, Montoya, & Rockwood, Reference Hayes, Montoya and Rockwood2017) to assess the indirect effect of work-induced sleep deprivation and account for the possibility of non-normal sampling distributions of this indirect relationship (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004). The effect size was −.030 for the indirect relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and OCB, through dehumanization of organizational leaders; the confidence interval (CI) did not include 0 (−.066; −.007). Thus, we can confirm the presence of mediation (Hypothesis 3).

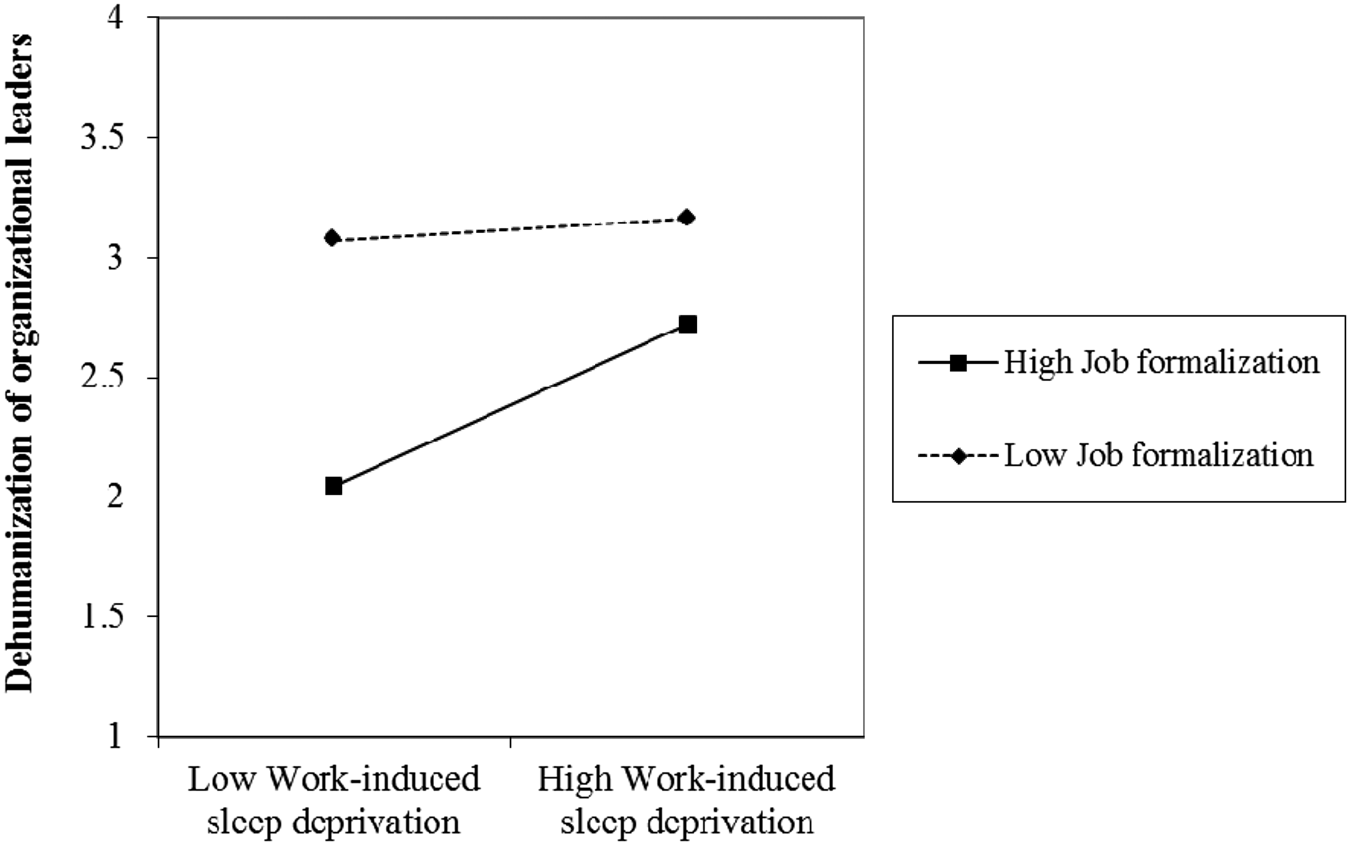

For Hypothesis 4, we calculated the work-induced sleep deprivation × job formalization interaction term to predict the dehumanization of organizational leaders (Model 3). The positive and significant interaction term (β = .146, p < .05) confirmed that the positive relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders was invigorated by job formalization, as we also depict in Figure 2. The corresponding simple slope analyses revealed that the relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders was significant at high levels of job formalization (β = .338, p < .001) but not at low levels (β = .046, ns), in further support of Hypothesis 4.

Fig. 2. Moderating effect of job formalization on the relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and dehumanization of organizational leaders.

Two relationships beyond the theoretical scope of this research, but still interesting to note, are the negative link between job formalization and dehumanization of organizational leaders (β = −.370, p < .001, Model 2) and the positive one between job formalization and OCB (β = .237, p < .001, Model 5). These findings imply that employees may be grateful for a certain amount of structure, created by job formalization (Adler & Borys, Reference Adler and Borys1996), such that they exhibit caring for organizational leaders and a willingness to undertake extra-role work activities. Yet the invigorating, moderating role of job formalization affirms our conceptual arguments, grounded in COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). That is, employees might appreciate some structure, unless they already are suffering from resource-draining, work-induced sleep deprivation. In this resource-deprived state, the added hardships caused by constraining job conditions and strict guidelines come to feel like threats that reinforce their resource depletion, so employees psychologically distance themselves from leaders (Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006) and refuse to undertake extra-role behaviors.

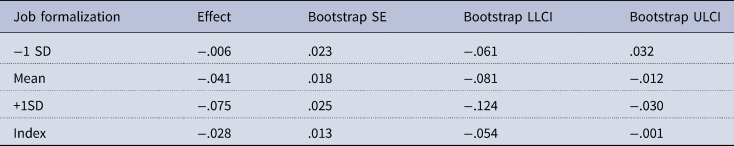

Finally, to check for the presence of moderated mediation, we compared the strength of the conditional, indirect, negative relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and OCB, through dehumanization of organizational leaders, at different levels of job formalization.Footnote 3 Table 3 indicates increasing effect sizes at higher levels of the moderator: from −.006 at one SD below the mean, to −.041 at the mean, to −.075 at one SD above the mean. The CI included 0 at the lowest level (−.061; .032), but at higher levels, the related CIs did not include 0 ([−.081; −.012] and [−.124; −.030], respectively). As a more direct assessment of moderated mediation, we used the index of moderated mediation and its corresponding CI. This index equaled −.028, and its CI did not include 0 (−.054, −.001). Taken together, these results affirmed that job formalization invigorated the negative indirect relationship between work-induced sleep deprivation and OCB, through dehumanization of organizational leaders, in support of Hypothesis 5 and our study's overall theoretical framework.

Table 3. Conditional indirect effects and index of moderated mediation

Notes: N = 207; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; LLCI, lower limit confidence interval; ULCI, upper limit confidence interval.

Discussion

This study contributes to previous scholarship by investigating the possible escalation of work-induced insomnia into diminished OCB, with special attention to pertinent factors that might explain or drive this process. Even if some prior studies reveal that employees' persistent sleep problems can compromise their organizational well-being (e.g., Barnes, Miller, & Bostock, Reference Barnes, Miller and Bostock2017; Jansson-Fröjmark & Lindblom, Reference Jansson-Fröjmark and Lindblom2010; Scott & Judge, Reference Scott and Judge2006; Toker et al., Reference Toker, Laurence and Fried2015), little research has specified the dangers of sleepless nights caused by work, including the potential to keep people from voluntary work efforts because of their perceptions of organizational leaders, let alone the exacerbating effects of constraining work environments in this process. By leveraging COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018), we have developed arguments that (1) employees reduce their work-related voluntarism in response to persistent sleep problems caused by work because they grow detached from the people in charge of the organization and (2) exposures to highly formalized work guidelines invigorate this process. The empirical findings provided support for these predictions.

As we demonstrated, employees suffering from low-quality sleep due to work are reluctant to devote significant time to voluntary work activities, because they dehumanize the people in charge (Densten, Reference Densten2001; Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone, & Rahn, Reference Jawahar, Kisamore, Stone and Rahn2012). In line with COR theory, employees respond to this resource-draining personal situation with indifference, in an effort to avoid self-damaging thoughts (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). This indifferent response seems justified, because employees believe organizational leaders do not care about them or their sleep quality (Wagner, Barnes, & Scott, Reference Wagner, Barnes and Scott2014). From a theoretical perspective, this finding reveals the possibility of a counterproductive cycle that employees enter, even without conscious awareness. Logically, employees should want to build high-quality relationships with organizational leaders who might help them deal with work-induced challenges (De Clercq, Fatima, & Jahanzeb, Reference De Clercq, Fatima and Jahanzeb2021; Duan, Lapointe, Xu, & Brooks, Reference Duan, Lapointe, Xu and Brooks2019). But instead, in their effort to retain their self-esteem, they develop psychological detachment from these leaders that in turn gives them an apparent justification to be ‘laggards’ who refuse to undertake OCB (Arabaci, Reference Arabaci2010; Kilroy et al., Reference Kilroy, Flood, Bosak and Chenevert2016). This behavioral response is not explicitly malevolent, but it likely compromises employees' organizational standing, such that they may become unintentionally complicit in worsening their personal and work lives (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, Whiting, Podsakoff and Blume2009).

As another notable theoretical implication, we establish that the dehumanization of organizational leaders is a more powerful mechanism by which work-induced sleep deprivation translates into diminished OCB if the workplace also imposes highly formalized job conditions (De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013; Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006). The very presence of red tape appears to trigger employees to hold organizational leaders responsible for personal hardships induced by work, which then prompts them to treat the leaders as impersonal objects (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018; Winstanley & Whittington, Reference Winstanley and Whittington2002). By explicating this invigorating role of job formalization, in combination with the harmful effect of such dehumanization for OCB, we provide theoretical insight into how the aforementioned negative cycle is more likely if organizations maintain strict policies. Even if formal structures can generate firm-level efficiency advantages (Juillerat, Reference Juillerat2010), they render individual employees vulnerable to the hardships of work-induced sleep problems (Bilal & Ahmed, Reference Bilal and Ahmed2017). Such vulnerability, in combination with their depersonalization of leaders, exacerbates the negative dynamic, directing employees away from discretionary activities that otherwise could enhance their own well-being and that of the organization (Jain, Giga, & Cooper, Reference Jain, Giga and Cooper2011; Lemoine, Parsons, & Kansara, Reference Lemoine, Parsons and Kansara2015).

Taken together, these insights provide a clearer sense of the ‘good soldier syndrome.’ Organizational decision makers must realize that the constraints stemming from highly formalized jobs strip sleep-deprived employees of any remaining commitment they might have toward leaders, with detrimental consequences for the likelihood that they contribute to the organization's success through effortful voluntarism. Whereas previous research outlines the direct harmful effects of a constraining organizational structure on employees' attitudes and behaviors (Chiaburu, Thundiyil, & Wang, Reference Chiaburu, Thundiyil and Wang2014; Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006), we clarify an indirect and equally relevant impact, such that job formalization fuels a negative process by which work-induced insomnia begets work-related complacency. An implied silver lining emerges from these findings though: Organizations can divert this harmful process by which work-induced sleep deprivation escalates into tarnished OCB, through dehumanization, by avoiding excessive job formalization and providing employees with sufficient flexibility in their work (Kaufmann, Borry, & DeHart-Davis, Reference Kaufmann, Borry and DeHart-Davis2019).

Limitations and future research

Some weaknesses of this study can inform continued research endeavors. First, we addressed the negative consequences of work-induced sleep deprivation, though without measuring which elements of the work environment produce sleep problems. These aspects might include psychological contract breaches (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Bordia, Restubog and Caines2018), workplace discrimination (Ragins et al., Reference Ragins, Ehrhardt, Lyness, Murphy and Capman2017), or negative perceptions of an organizational transformation (Rafferty & Jimmieson, Reference Rafferty and Jimmieson2017). Continued studies could specify and measure these different work challenges to determine which of them has the greatest impact on the extent to which employees respond with dehumanization of organizational leaders and reduced OCB. Similarly, we considered employees' behavior toward organizational leaders in general, not any specific leader or supervisor. It would be useful to investigate the connection between insomnia caused by a specific source, such as an abusive supervisor, and the extent to which employees psychologically detach from that unique person (Huang, Lin, & Lu, Reference Huang, Lin and Lu2020).

Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study demands some caution in terms of possible reverse causality. If employees gain a sense of personal accomplishment by offering voluntary contributions to the organization, they also might develop positive feelings about their leaders, which could help them feel more relaxed and achieve better sleep. Our hypotheses are grounded in the well-established framework of COR theory – according to which challenging personal situations drive employees toward behaviors that enable them to avoid further depletion in their self-esteem resources and express their frustrations (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001) – but it still would be useful to measure the focal constructs at different points in time and assess cross-lagged effects of work-induced sleep deprivation on OCB through dehumanization of organizational leaders (Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart, & Lalive, Reference Antonakis, Bendahan, Jacquart and Lalive2010). It also would be interesting to test for variations in the extent to which sleep-deprived employees avoid OCB according to the specific type of OCB they perform. Perhaps they strongly reject discretionary efforts that require significant energy (e.g., detection and resolution of organizational problem situations) but continue to engage in more passive efforts (e.g., personal initiatives to avoid wasting paper) (Ocampo et al., Reference Ocampo, Acedillo, Bacunador, Charity, Lagdameo and Tupa2018; Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, Reference Organ, Podsakoff and MacKenzie2006).

Third, our focus on the invigorating role of job formalization aligns with the argument that red tape tends to undermine the quality of the relationships that employees have with their organization's leadership (Huang & Van de Vliert, Reference Huang and Van de Vliert2006) and, more generally, that employees' perceptions of structural work arrangements influence the ways they choose to deal with resource-draining personal situations (Moquin, Riemenschneider, & Wakefield, Reference Moquin, Riemenschneider and Wakefield2019; van Ruysseveldt & van Dijke, Reference van Ruysseveldt and van Dijke2011). Thus, any benefits of job formalization might be overpowered by its negative implications, in terms of the significant energy depletion it evokes (Bilal & Ahmed, Reference Bilal and Ahmed2017), especially among employees who already suffer persistent sleep shortages. Qualitative studies could provide additional insights into the negative and positive influences of specific types of job formalization on employees' work functioning, as well as the distinct personal circumstances in which the former dynamics supersede the latter. Other contextual factors, beyond job formalization, could serve as catalysts of these processes too, such as dysfunctional organizational politics (Harris, Harris, & Harvey, Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007) or unfair decision-making processes (Michel & Hargis, Reference Michel and Hargis2017). Unique personal factors also may make employees more or less likely to exhibit negative reactions to their persistent sleep problems, such as neuroticism (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, Reference De Hoogh and Den Hartog2009), social cynicism (Alexandra, Torres, Kovbasyuk, Addo, & Ferreira, Reference Alexandra, Torres, Kovbasyuk, Addo and Ferreira2017), or negative affectivity (Panaccio, Vandenberghe, & Ayed, Reference Panaccio, Vandenberghe and Ayed2014).

Fourth, the study sample includes employees of one organization, in one industry (oil distribution) and one country (Angola). This research design helped minimize the potential presence of unobserved differences associated with pertinent organizational, industry, or country factors. Moreover, our conceptual arguments are industry-neutral, and we accordingly would anticipate that the strength, but not the nature, of the theorized relationships might vary across industries. It would be helpful to investigate how relevant industry characteristics may interfere with the tested theoretical framework though. For example, people employed by firms in very competitive markets may be more understanding or forgiving of work-induced hardships that disrupt their sleep (Lahiri, Pérez-Nordtvedt, & Renn, Reference Lahiri, Pérez-Nordtvedt and Renn2008), so their reactions to this situation might be less extreme. As mentioned in the Research method section, we anticipate two contrasting dynamics with regard to Angola's cultural profile: Its uncertainty avoidance may elicit strong negative reactions to sleep shortages, but its collectivism and associated concerns about organizational well-being may subdue those reactions. The empirical support we find for our research hypotheses suggests the former dynamic might be more prevalent than the latter. It would be insightful to perform dedicated comparisons to detail how specific cultural values may influence employees' reactions to work-induced insomnia (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010).

Practical implications

For managers, this study directs attention to the critical challenges that arise when employees cannot sleep well at night, and the problem is caused by their work. Specifically, it leaves employees indifferent to the organization's leadership and uninterested in work activities that are not explicitly demanded by their jobs (Pooja, De Clercq, & Belausteguigoitia, Reference Pooja, De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2016). For managers, these effects might be difficult to identify; employees are unlikely to talk about their sleep habits at work, because they seemingly belong to the private sphere (regardless of whether they are caused by work-related difficulties). In addition, employees might avoid discussing their personal challenges because they want to appear strong and able to cope with work demands. Therefore, managers need to take the initiative to identify employees who suffer from adverse work conditions and might be suffering from insomnia (Barnes, Miller, & Bostock, Reference Barnes, Miller and Bostock2017). Then they should provide practical recommendations for how to keep difficult work situations from spilling over into personal lives, through formal training sessions or informal coaching on the job (Jacobs & Park, Reference Jacobs and Park2009; Lin & Tsai, Reference Lin and Tsai2020). They also might probe employees empathetically about nonwork-related reasons for their insomnia and offer advice for how to tackle those issues – efforts that should reduce the chances that employees blame their leaders for the negative situation.

In addition to this broad recommendation to recognize and help employees deal with the challenge of work-induced sleep deprivation, this study provides in-depth suggestions for how to address the persistent risks of insomnia among employee ranks, which can arise from employees' innate characteristics, as well as external pressures in the workplace (Haar & Roche, Reference Haar and Roche2013; Rafferty & Jimmieson, Reference Rafferty and Jimmieson2017). Notably, our results regarding the intensifying role of job formalization should not be taken as a suggestion to eliminate formality altogether, in that some reasonably limited rules can provide relevant anchors to help employees learn how to complete their job tasks efficiently (Adler & Borys, Reference Adler and Borys1996). But it remains up to organizational leaders to prevent this formalization from growing into an excessive red tape that limits employees' versatility and work-related choices. The key is to find a healthy balance between implementing some necessary structure and allowing employees to explore different methods to do their jobs. That is, to the extent that employees can rely on supportive structural arrangements and practices, they may experience their work-induced insomnia as less threatening to their professional and personal well-being, which may lead to more positive emotions toward organizational authorities and stronger motivations to help their employer with their selfless efforts and contributions.

Conclusion

This study adds to prior research by investigating the harmful effect of a specific source of personal strain (work-induced sleep deprivation) on employees' propensity to stay away from OCB, as well as the roles that their dehumanization of organizational leaders and beliefs about job formalization have in this process. Their feelings of detachment toward leaders represent important conduits through which the hardships of sleepless nights, caused by work, undermine their voluntary work efforts. The viability of this explanatory path depends on the amount of red tape that employees confront in attempting to do their jobs. We hope this research can serve as a stepping stone for further studies into how ‘good soldiers’ might persist in their efforts to add to their organization's success, with unbridled voluntarism and OCB, even if they feel drained by challenging work conditions that undermine their sleep.