Introduction

The extent to which people work from home (WFH), an element of remote-, virtual-, flexible-, and tele-work, has increased in recent years (Charalampous, Grant, Tramontano, & Michailidis, Reference Charalampous, Grant, Tramontano and Michailidis2019; Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017; Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario, & Peixoto, Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023; Semuels, Reference Semuels2020b). This has been fueled by the growing sophistication of digital technologies, employee preferences, and organizational cultures that value flexibility, innovation, and autonomy (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Reference Delanoeije and Verbruggen2020; Grant, Wallace, & Spurgeon, Reference Grant, Wallace and Spurgeon2013; Rothbard, Reference Rothbard2020; Wörtler, Van Yperen, & Barelds, Reference Wörtler, Van Yperen and Barelds2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has been an additional and stronger motivating factor for employees to WFH. In the first lockdown, the prevalence of WFH soared – in some countries, more than 50% of the workforce experienced WFH at various times (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Jones, Reference Jones2020).

Thus, while WFH is not new, its rapid growth during the COVID-19 era brought about five key differences. First, although WFH had been growing rapidly in popularity before 2020 (Charalampous et al., Reference Charalampous, Grant, Tramontano and Michailidis2019; Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017), it was not widely used (Wang, Liu, Qian, & Parker, Reference Wang, Liu, Qian and Parker2021) and regarded as a privilege (Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017). The opportunity to WFH had mostly been granted to professionals and other skilled workers depending on the nature of the industry, the culture of the organization, and the desires of the employee. However, COVID-19 has meant that, in multiple countries, most desk-based employees worked remotely for long periods. Second, WFH had been predominantly voluntary, accompanied by organizational or managerial approval (Rothbard, Reference Rothbard2020), whereas during the pandemic, WFH has been largely mandated by governments and implemented by employers. Third, previously employees could gradually acclimatize to WFH, whereas COVID-19-enforced WFH happened very suddenly, at least for the first time, without employees having time to prepare their home workspaces properly with appropriate furniture and technology, or ready themselves psychologically for the pandemic and to WFH effectively on an ongoing basis. In addition, many employees initially lacked training in the software and processes needed for working and meeting remotely (Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas, & Rolls, Reference Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas and Rolls2021). Fourth, many teleworkers had previously been working some days in the office and some days at home (Cooper & Kurland, Reference Cooper and Kurland2002) in what has been termed blended working arrangements (Wörtler, Van Yperen, & Barelds, Reference Wörtler, Van Yperen and Barelds2021) or hybrid models (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a). However, for some in lockdown, it was (or still is) every day at home for lengthy and uninterrupted periods. Fifth, prior to COVID-19, an employee WFH was often the only adult at home, whereas during lockdown, many households have had everyone at home.

These five changes potentially increase the demands placed on many employees and undermine their performance and wellbeing while WFH in lockdown. This has been highlighted in reports by academics (e.g., Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale, & Scherer, Reference Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale and Scherer2020; Felstead & Reuschke, Reference Felstead and Reuschke2020; Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai, & Bendz, Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020), professional bodies (e.g., American Psychological Association [APA], 2021; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a, 2020b; Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology [Campion, Zhu, Campion, & Alonso, Reference Campion, Zhu, Campion and Alonso2020]), and the media (e.g., Hern, Reference Hern2020; Semuels, Reference Semuels2020a, Reference Semuels2020b). Anxiety and other stress-related outcomes rose as the virus gained momentum, cases and deaths rose, income was reduced, and in some cases, jobs and businesses were lost. During lockdown, taking care of children and other household tasks remained a contentious gender issue (Craig, Reference Craig2020; Feng & Savani, Reference Feng and Savani2020), and workloads grew for many (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Jones, Reference Jones2020). Under these constrained conditions, many employees felt increased performance pressure, strengthened by perceptions of managerial surveillance (Felstead & Reuschke, Reference Felstead and Reuschke2020; Hern, Reference Hern2020; Naughton, Reference Naughton2020). These demands increased workers' levels of stress, already elevated by the pandemic (American Psychological Association [APA], 2021; Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee and Barlow2020; Trougakos, Chawla, & McCarthy, Reference Trougakos, Chawla and McCarthy2020). While many organizations have provided emotional and other forms of support to their staff (Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis, & Omari, Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021), these resources may not have sufficiently helped them to cope.

Regarding the ‘continuing recontextualization of work’ for remote employees (Donnelly & Johns, Reference Donnelly and Johns2020: 2), it is important to investigate people's experiences of WFH during a sudden lockdown. Our study aims to contribute to understanding the experience of WFH during the pandemic and answer the research question: What factors have impacted employee performance and wellbeing while working from home during lockdown? Although the pandemic has caused major disruptions to the world of work since early 2020, and most countries have been through COVID-19 surges and several periods of lockdown, our study aims to explore employees' initial experiences of WFH, during New Zealand's first compulsory lockdown, beginning in March 2020. The theoretical foundation for our study is the Job Demands-Resources framework (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017) – the demands of WFH have been exacerbated by COVID-19 but mitigated somewhat by access to additional resources (Bilotta, Cheng, Davenport, & King, Reference Bilotta, Cheng, Davenport and King2021; Franken et al., Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021).

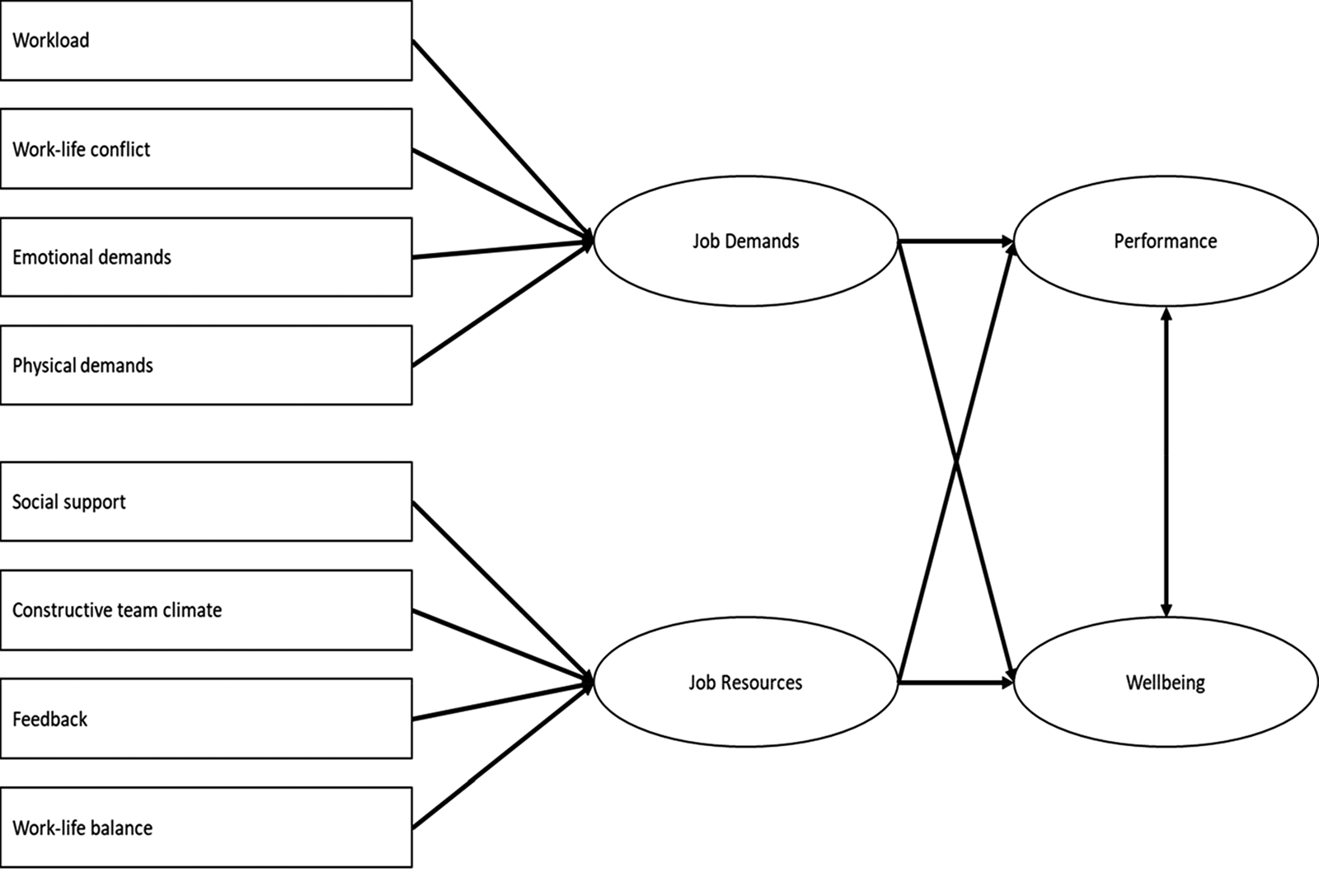

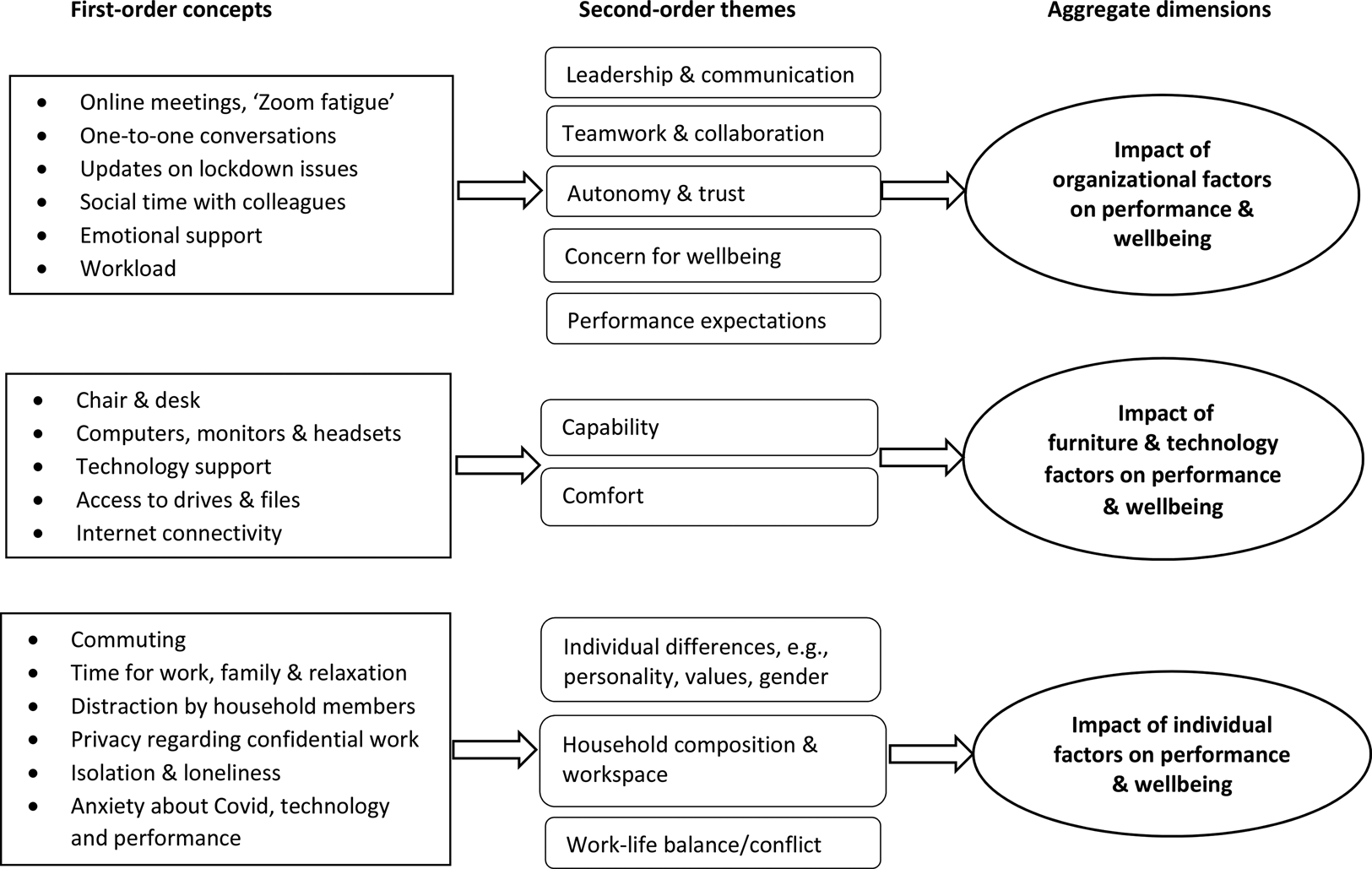

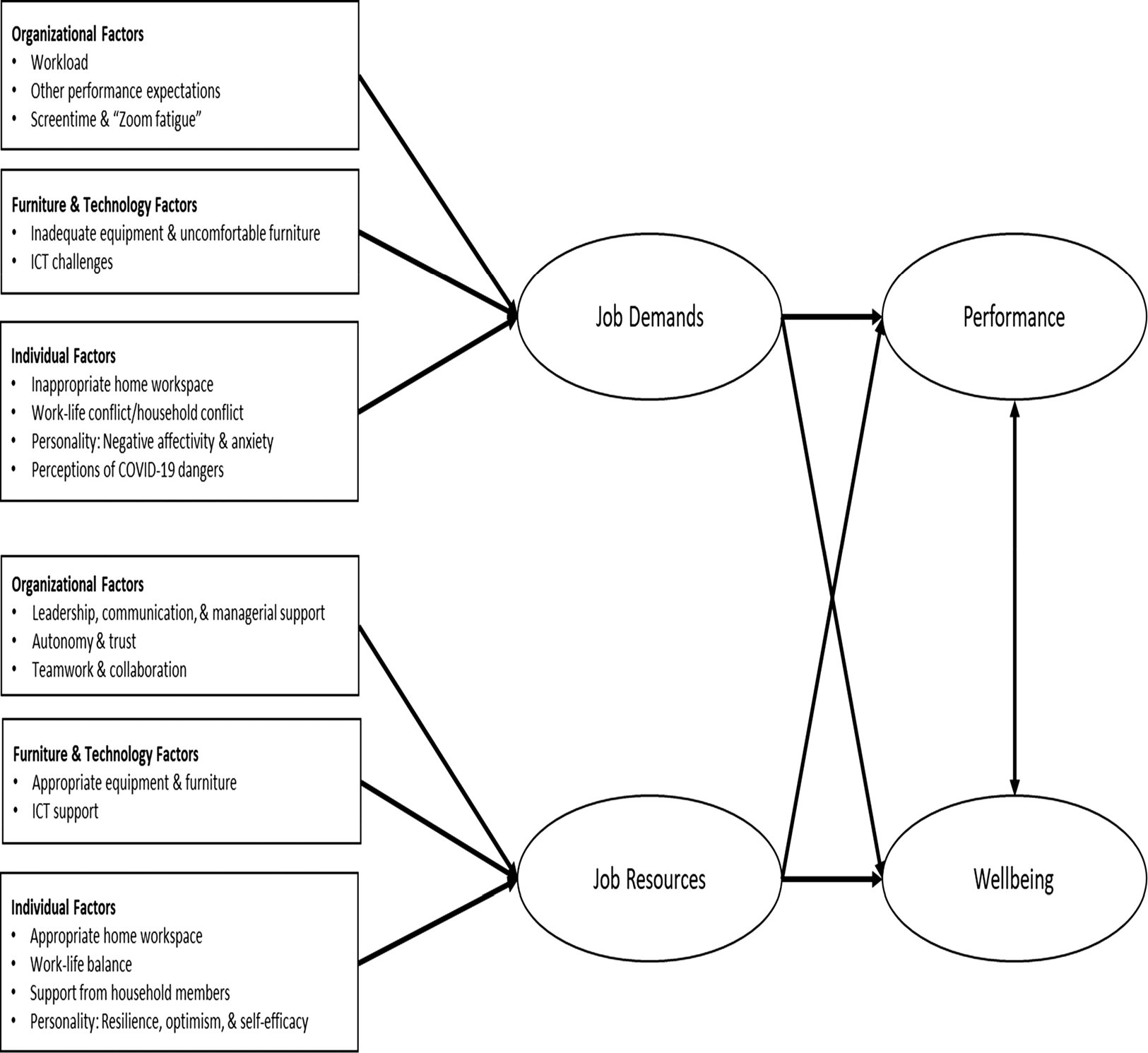

Our study makes two key contributions. First, we present qualitative insights into a wide range of factors impacting WFH during lockdown. These new understandings will inform various fields of literature, including stress and wellbeing, organizational behavior, organizational change, human resource management, and ergonomics. Second, we present figures that identify a wide array of factors influencing performance and wellbeing while WFH during lockdown and indicate how the demands and resources associated with each factor contribute to positive and negative outcomes. Figure 1 is a JD-R model, based on Bakker and Demerouti's (Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017) conceptual studies. Figure 2 is the data structure which identifies first-order concepts, second-order themes and aggregate dimensions. Figure 3 draws on the JD-R model to show the interplay of demands and resources for employees in our study forced to WFH. These figures yield theoretical insights and provide a practical assessment framework whereby managers can evaluate what demands their employees are likely to face and what resources they and the organization can provide to mitigate these demands, enabling performance and maintaining or even enhancing wellbeing.

Figure 1. Job demands and resources while working from home.

Figure 2. Data structure.

Figure 3. Model of key job demands and resources while working from home during lockdown.

Literature review

The benefits and costs of WFH for employees

Prior empirical studies have revealed that a key advantage for remote workers has been better work–life balance, resulting in higher engagement and lower stress (Anderson, Kaplan, & Vega, Reference Anderson, Kaplan and Vega2015; Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Reference Delanoeije and Verbruggen2020; Grant, Wallace, & Spurgeon, Reference Grant, Wallace and Spurgeon2013; Koslowski, Linehan, & Tietze, Reference Koslowski, Linehan and Tietze2019; Maruyama, Hopkinson, & James, Reference Maruyama, Hopkinson and James2009). The autonomy granted as to when to work, let alone where, leads to improved wellbeing (Perry, Rubino, & Hunter, Reference Perry, Rubino and Hunter2018; Wörtler, Van Yperen, & Barelds, Reference Wörtler, Van Yperen and Barelds2021). Previous studies of WFH have also reported greater employee productivity compared to the office (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Reference Delanoeije and Verbruggen2020; Van Dyne, Kossek, & Lobel, Reference Van Dyne, Kossek and Lobel2007). However, researchers have argued that while productivity may increase, it is accompanied by increased stress for those who find it hard to switch off from work activities (Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017) and experience guilt at receiving this ‘privilege’ (Felstead & Henseke, Reference Felstead and Henseke2017) or discomfort at seeming to be outsiders (Koslowski, Linehan, & Tietze, Reference Koslowski, Linehan and Tietze2019). Some perceive diminished career progress through lack of visibility and reduced access to collegial networks, informal learning, coaching, and mentoring (Cooper & Kurland, Reference Cooper and Kurland2002), and suffer from isolation and loneliness (Bentley, Teo, Tan, Bosua, & Gloet, Reference Bentley, Teo, Tan, Bosua and Gloet2016; Golden, Veiga, & Dino, Reference Golden, Veiga and Dino2008). Blurring the boundaries between home and work potentially creates work–life conflict when territory and time are contested by different actors (Koslowski, Linehan, & Tietze, Reference Koslowski, Linehan and Tietze2019; Reissner, Isak, & Hislop, Reference Reissner, Isak and Hislop2021).

Job demands and resources

The theoretical foundation for this study on WFH during lockdown derives from several models that address performance and wellbeing at work. First, the widely cited JD-R framework (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017; Roczniewska, Smoktunowicz, Calcagni, Schwarz, Hasson, & Richter, Reference Roczniewska, Smoktunowicz, Calcagni, Schwarz, Hasson and Richter2022) shows how various demands in the work environment can undermine performance and wellbeing (with a strong focus on burnout), with the impact being mitigated by the availability and use of resources, both organizational and personal. Demands include ‘high work pressure, an unfavourable physical environment, and emotionally demanding interactions…’ (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007: 312). Resources are: ‘those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulate personal growth, learning, and development’ (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017: 274). Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari, and Isaksson (Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017) categorize work resources on four levels (the individual, group, leader, and organization), all contributing to employee performance and wellbeing. Noting the focus on individual-level factors in research, Roczniewska et al. (Reference Roczniewska, Smoktunowicz, Calcagni, Schwarz, Hasson and Richter2022) showcase the importance of unit (group and organization) resources and demands. Further, regarding resources, researchers have distinguished between job resources (within the organization) and personal or individual resources, usually in terms of personality traits and skills (e.g., Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017; Franken et al., Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017).

A second and complementary theoretical approach is Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), which proposes that wellbeing declines when valuable resources, personal, social, and material (Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018), are absent, threatened, lost, or cannot be obtained. People aim to protect their resources by using them judiciously and replenishing them when possible. For example, the support of others, at work and elsewhere, allows people the comfort of knowing they are not alone in lockdown. However, people may be reluctant to overuse sources of support and may be prompted by notions of self-reliance in declining or not asking for support or saving them for later (Smollan & Morrison, Reference Smollan and Morrison2019).

Usefully, JD-R acknowledges the bidirectional relationship between performance and wellbeing. Performance at work is based on individual differences, such as ability, motivation, and personality, along with organizational factors, such as leadership, organizational culture, and technology (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017). Wellbeing is a construct sometimes taken as the absence of stress and burnout or, more positively, as stemming from mental health, job satisfaction, engagement, and positive affect (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015; Danna & Griffin, Reference Danna and Griffin1999; Sonnentag, Reference Sonnentag2015). Wellbeing can be both trait, a dispositional tendency to positive or negative affect, or state, depending on factors in the environment, such as work demands. A wide body of research over many years has indicated how low wellbeing results in poor performance, poor decisions, conflict, and absenteeism (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015; Danna & Griffin, Reference Danna and Griffin1999; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017; Sonnentag, Reference Sonnentag2015). Conversely, when employees perform well, aided by support and feedback from others, wellbeing is enhanced (Bakker, Hetland, Olsen, & Espevik, Reference Bakker, Hetland, Olsen and Espevik2019).

Drawing on JD-R, a decline in wellbeing from work demands negatively impacts performance, while the productive use of resources enhances wellbeing and thereby performance (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015; Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017). Evidence supports this mutual reinforcement of wellbeing and performance: People who have a sense of competence or mastery have been shown to have higher wellbeing, and employees with high levels of wellbeing are positioned to perform well when not distracted by negative affect (Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017; Perry, Rubino, & Hunter, Reference Perry, Rubino and Hunter2018). Figure 1 is a model of JD-R in the context of WFH.

Demands and resources while WFH during lockdown

WFH during a pandemic imposes demands on employees that go beyond those normally associated with remote work, such as a sense of isolation and being disconnected from the physical work environment and the many formal and informal interactions that occur within it (Brooks, Reference Brooks2021; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Qian and Parker2021). Studies to date show that the demands of WFH during the pandemic include meeting performance expectations (from supervisors, colleagues, customers, and other stakeholders), inadequate technology and furniture, communicating with others, and dealing with the needs and interruptions of household members – all permeated by anxiety and uncertainty regarding the spreading COVID-19 virus (Anicich et al., Reference Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale and Scherer2020, Malinen, Wong, & Naswall, Reference Malinen, Wong and Naswall2020; Perry, Carlson, Kacmar, Wan, & Thompson, Reference Perry, Carlson, Kacmar, Wan and Thompson2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Qian and Parker2021). Before the pandemic, many managers were opposed to WFH because it reduced their control over employees (Felstead, Jewson, & Walters, Reference Felstead, Jewson and Walters2003). Perceptions of managerial surveillance pre-pandemic (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Reference Delanoeije and Verbruggen2020) have been exacerbated by reports of increased use of monitoring software, aiming to detect ‘shirking from home’ (Hern, Reference Hern2020). There is evidence that increased surveillance has led to extra hours at work, more anxiety, lower trust, and increased cynicism (Hern, Reference Hern2020; Naughton, Reference Naughton2020). In addition, employees who WFH are often expected to pay for the costs of furniture, devices, and internet connections (Brooks, Reference Brooks2021; Campion et al., Reference Campion, Zhu, Campion and Alonso2020). Beyond these costs, many employees may struggle with inadequate space, technology, and interrupted connectivity, all compromising performance and wellbeing. Given that many employees spent little or no time WFH pre-pandemic, the demands of ongoing work weeks in unsuitable conditions have taken their toll on the physical and mental health of many workers (Davis, Kotowski, Daniel, Gerdsing, Naylor, & Syck, Reference Davis, Kotowski, Daniel, Gerdsing, Naylor and Syck2020).

To cope with these demands, employees have found various resources valuable. Within the organization these include teamwork, autonomy, communication, and support from supervisors, senior management, colleagues, and information and communication technology (ICT) departments (Bilotta et al., Reference Bilotta, Cheng, Davenport and King2021; Franken et al., Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021, Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020). Individual resources include personality traits, such as self-efficacy, emotional maturity, optimism, and hope (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hetland, Olsen and Espevik2019; Franken et al., Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021; Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nielsen, Ogbonnaya, Känsälä, Saari and Isaksson2017) as well as support from family and other household members (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Carlson, Kacmar, Wan and Thompson2022). Time is also a resource (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001; Reissner, Izak, & Hislop, Reference Reissner, Isak and Hislop2021) that increased for some by the lack of commuting during lockdown but decreased by higher workloads and tighter deadlines. Higher workloads have resulted in a draining of energy (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020b) and a lack of time that may have helped meet the needs of others at home (Craig, Reference Craig2020; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Carlson, Kacmar, Wan and Thompson2022).

Therefore, a key question is whether higher productivity has led to enhanced wellbeing or undermined it. Burnout, a likely outcome of prolonged work overload in difficult conditions (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015), may not manifest if the lockdown period is relatively short. That said, keeping up with challenging expectations over time may lead to anxiety and reduced self-efficacy.

Understanding the phenomenon of WFH requires a consideration of the contextual complexity of ‘time, place, and people’ (Glaser, Reference Glaser2002: 24) in assessing demands and resources. This paper focuses on micro-level experiences of workers, including their perceptions of meso-level group and organizational cultures, policies, and practices (Roczniewska et al., Reference Roczniewska, Smoktunowicz, Calcagni, Schwarz, Hasson and Richter2022) relating to the macro-environment – WFH during a nationwide lockdown triggered by a pandemic.

Method

Methodological foundation

Interpretive research facilitates the investigation of new phenomena by exploring actors' socially constructed multiple realities (Charmaz & Thornberg, Reference Charmaz and Thornberg2021). As noted before, WFH during the pandemic has been qualitatively different from the past in terms of the global nature of the phenomenon, the very sudden, involuntary, and disruptive implementation of WFH, the wide range of occupations required to WFH, and the complex nature of employees' household environments. Of special interest is how employees who WFH construct boundaries of ‘time, space and objects’ (Reissner, Isak, & Hislop, Reference Reissner, Isak and Hislop2021: 297) in the work–life interface. Therefore, we sought to capture employee experiences of WFH during lockdown in a global pandemic, a demanding new reality.

The research sites and participants

On 23 March 2020, New Zealand was placed in nationwide lockdown due to COVID-19; many restrictions were lifted on 13 May, and on 11 June workplaces and schools re-opened (Radio New Zealand [RNZ], 2021). Two organizations in New Zealand were surveyed regarding employee experiences of WFH during lockdown. Company A is a large financial services organization; company B is a medium-sized professional services firm. Both companies are predominantly based in Auckland, with employees mostly in open-plan offices. The organizations requested data collection to assess their response to the COVID-19 lockdown, and the efficacy of the support and interventions provided to employees, with a view to further potential lockdowns. Data were collected from company A in May 2020, while employees were still in the first lockdown. Data were collected from company B as lockdown ended from mid-June 2020, as most staff were returning to the physical office after approximately two months of remote working.

In company A, data were collected from 504 employees, representing 60% of the 831 staff. Respondents were drawn from all departments and were representative of the organization overall, 71% being female, 20% were younger than 30 years, and with an even spread across age brackets (29% between 30 and 39 years, 26% between 40 and 49 years, and 24% over 50 years). In company B, data were collected from 151 employees – representing 63% of the 240 staff. The sample reflected the demographics within the organization: 65% female, and a majority under 40 years (44% younger than 30 years, 36% between 30 and 39 years, 15% between 40 and 49 years, and 4% over 50 years).

Materials and procedure

We conducted anonymous online surveys for both organizations and included open-ended responses, which comprise the data we analyze here. While we have used the JD-R model as the theoretical foundation for our study (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017), the qualitative comments we sought (at the participating organizations' request) were not explicitly about demands and resources but more generally about their experiences through the pandemic. In addition to the survey questions, we asked respondents in company A to provide written comments: first, to outline any concerns or negative experiences relating to WFH, and second, what they had most appreciated or enjoyed about WFH. Finally, we asked participants to add any other information they wanted to share about WFH or lockdown or their anticipated resumption of working onsite. In company B, we asked the same survey questions and open-ended questions for company A (outlining concerns and describing what was appreciated), and in addition we prompted employees to provide their views on what, if anything, they missed about working in the office, any ICT issues they had or additional support they needed, and to provide feedback on the organization's communications during lockdown.

A survey link was disseminated via an organization-wide email invitation from the chief people officer of company A and the chief executive officer of company B, promoted on the organizations' intranets. The survey was identified as independent of the organization, conducted by university researchers, and anonymous.

Data analysis

To interrogate the qualitative data, we used the Gioia method (Gioia, Reference Gioia2021; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013; Patvardhan, Gioia, & Hamilton, Reference Patvardhan, Gioia and Hamilton2015). Designed to instill rigor in qualitative research (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013), this method is used to identify first-order concepts, often based on participants' own words; these are condensed into second-order, theory-centered themes, and, finally, the themes are clustered into aggregate dimensions (Gioia, Reference Gioia2021).

Repeated readings of the comments identified dominant first-order concepts, both positive and negative, such as the appreciated absence of long commutes, the pleasures of extra family and personal time, and the challenges of unsuitable workspaces and equipment. A series of discussions between the authors led to generating, discarding, and refining the second-order themes. For example, the first-order concepts of available chairs, desks, internet connectivity, and access to drives and files led to the second-order themes of capability and comfort. These themes were then conceived as the aggregate dimension of The impact of furniture and technology on performance and wellbeing. Similar approaches were used for the remaining data. The dimension of furniture and technology is positioned between organizational and individual factors because it has elements of both. Figure 2 reproduces our data structure.

Findings

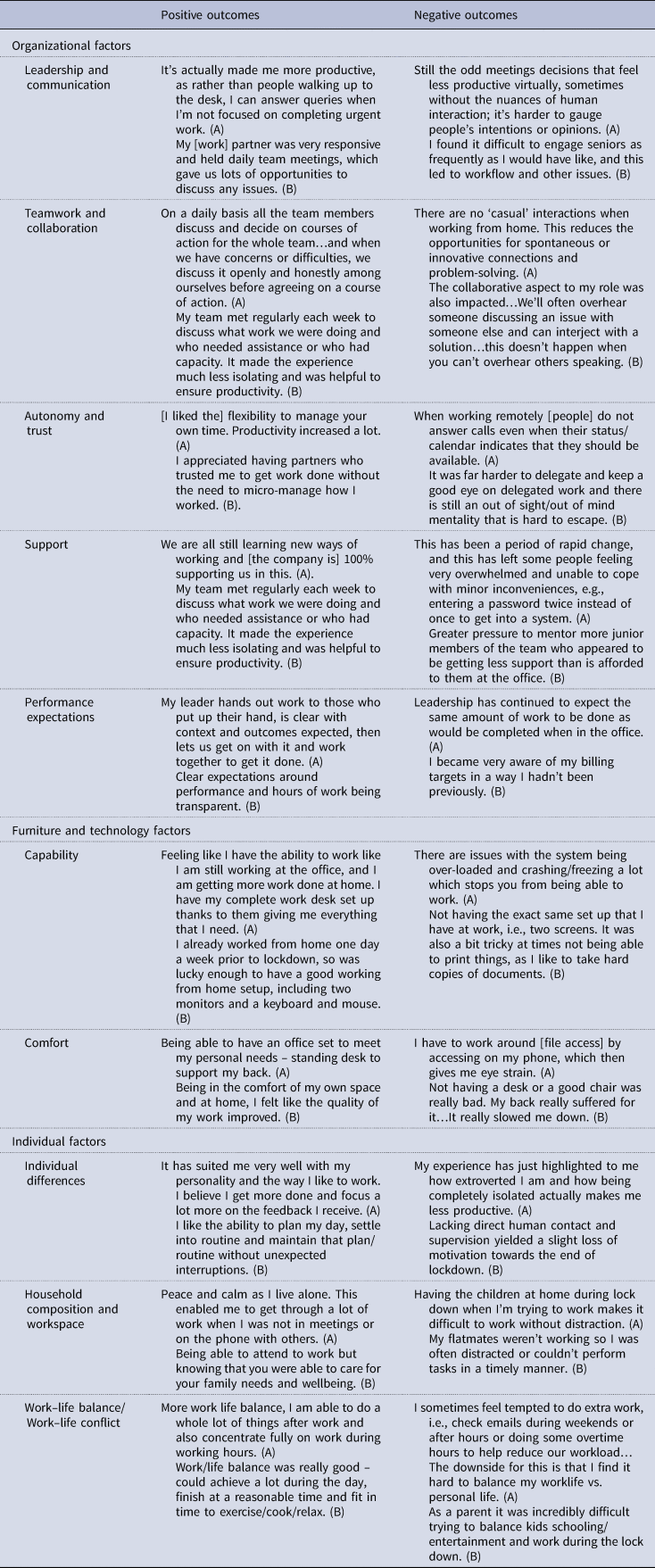

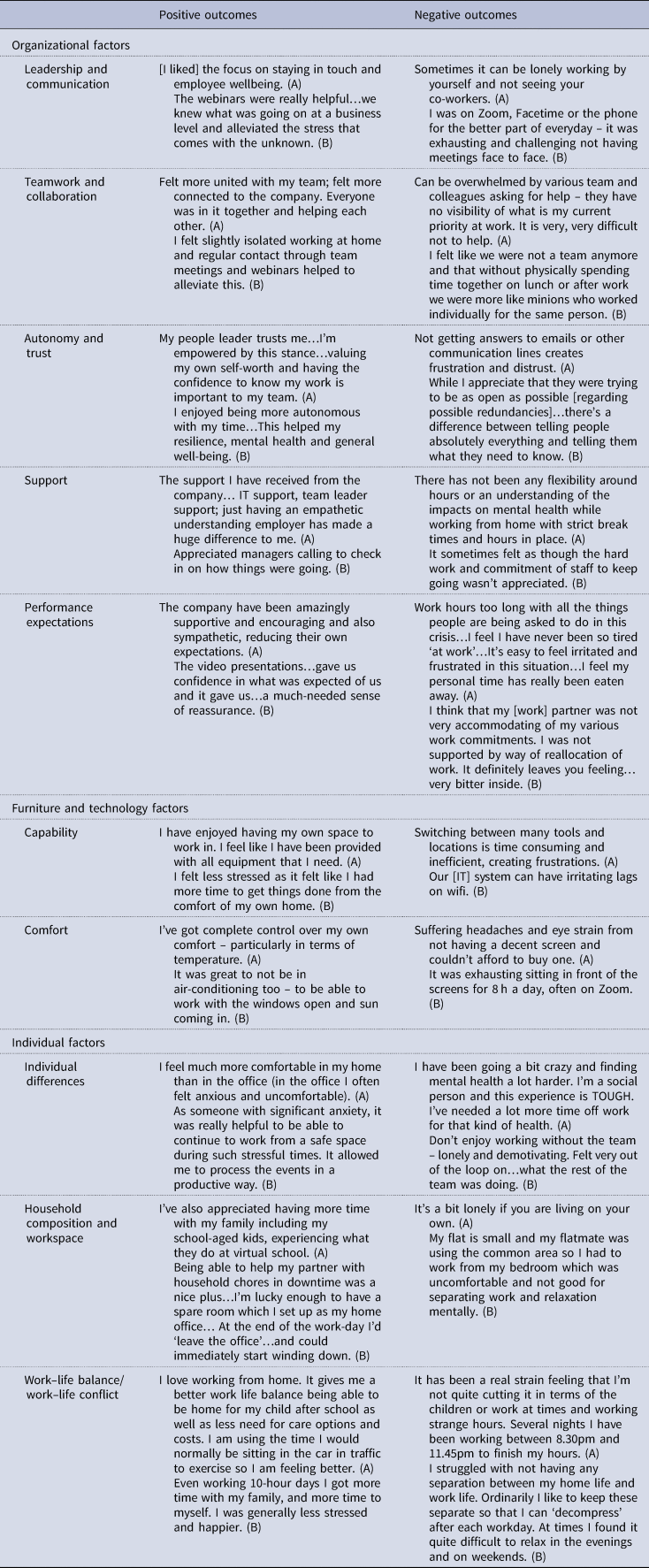

The written responses by employees in the two companies provided a wealth of data on demands and resources. Our research question focused on what factors might be different about worker experience of WFH during lockdown, compared to earlier, pre-pandemic studies, and how these factors contributed to performance and wellbeing. In Tables 1 and 2 below, we display quotes that represent the first-order concepts affecting performance (Table 1) and wellbeing (Table 2). These are grouped into the table headings (second-order themes), such as leadership/communication and teamwork/collaboration, under the three aggregate dimensions of organizational factors, furniture and technology factors, and individual factors. We note that, while we have identified second-order factors and aggregate dimensions, there are overlaps, given people's complex experiences of WFH. In terms of resources, for example, communication is an aid to teamwork and collaboration, and contributes to a perceived organizational concern for wellbeing, but, especially in WFH, communication is also affected by technology and household dynamics. Similarly, the advantage of having suitable furniture and technology in one's home can be undermined by inadequate management or ICT support, and the demands of other household members to use the same furniture, devices, and spaces. Some comments also indicate that an issue can impact both performance and wellbeing. For example, one participant appreciated how improved work–life balance ‘has really reduced stress in our household and would have made me more productive because of this.’

Table 1. Examples of impact of WFH on performance

Table 2. Examples of impact on WFH on wellbeing

Impacts of WFH on performance

Given the many types of workspaces, perceptions of organizational issues, individual attributes, and household configurations, it was unsurprising to find a wide range of positive and negative WFH experiences of demands and resources related to performance (Table 1).

Organizational factors

Leadership and communication: Participants referred to various forms of communication during lockdown: whole-company emails, video conferences and other media fronted by senior leadership, departmental/team communication, and one-to-one vertical, horizontal, and dotted-line communication. In both organizations, participants appreciated updates about operational issues, the use and delivery of equipment, and guidelines on remote work and the various platforms that enabled it. With fewer interruptions for some, productivity improved. Others, however, struggled with ‘Zoom fatigue,’ intermittent internet connectivity, and the inability to ‘read’ people as well as they could in face-to-face situations.

Teamwork and collaboration: For some, online team meetings were an adequate proxy for the onsite variety, but for others, colleagues were literally and figuratively too distant. On the positive side, comments were made about how teams (and their leaders) had gone to extra lengths to update others on project progress, share ideas, and discuss new ways of working. Negative experiences focused on the lack of spontaneous opportunities to overhear conversations and contribute to them, which otherwise commonly occurred in their open-plan offices. Some noted that it required more effort to initiate conversations by telephone or virtually, and they were reluctant to do so. One participant, who had been allowed to WFH pre-lockdown and often felt excluded, noted that it was comforting that lockdown ‘has put us all on a level playing field.’

Autonomy and trust: Given that managers cannot see their staff when they are WFH, they have little option but to trust them more and allow them the freedom to make decisions. Participants perceived that this led to better performance when they could make decisions more quickly, such as addressing client concerns. However, some believed that other staff members were not performing well enough, regardless of their home circumstances and responsibilities.

Support: When participants perceived that their wellbeing was prioritized by the organization, and instrumental, informational, and emotional support were provided, they believed that their performance improved. Conversely, those who perceived a lack of support believed it was detrimental to performance. Dealing with heavy workloads and new communication technologies – with insufficient support – left some employees floundering.

Performance expectations: Three key elements relating to performance expectations were clarity of communication, workload, and recognition of home circumstances by the organization or manager. Those who felt that the organization was being realistic and fair reported higher personal productivity. Interestingly, some participants who believed that targets were too high or deadlines were too tight still felt the need to put in longer hours. Some junior staff did not know what to do with their time when they were not assigned tasks, with this being particularly salient for workers with client billing targets, for example, ‘I had very little idea of what work I was expected to do…when there was no work.’

Furniture and technology factors

Capability: Employees WFH had usually purchased their furniture and equipment, which were also used for personal matters. The two organizations endeavored to provide extra items necessary for productive work in employees' homes. Participants who reported having adequate desks, chairs, devices (PCs/laptops, monitors, printers, etc.), internet connectivity, and file access, noted how this enabled task performance. However, others lamented the loss of an ergonomically designed chair or a second monitor, and instead struggled with uncomfortable furniture and a single, smaller laptop screen. Some also had to manage with poor internet connections and, at least initially, a lack of knowledge of accessing online meetings, software, drives, and files.

Comfort: Participants who felt that their home furniture and equipment were suitable were satisfied with the physical comforts they offered. However, it is unsurprising that those who labored in inadequate physical working conditions complained of various ailments, such as backache, headache, eye strain, and sore muscles. Some were working on dining-room tables, couches, and even their beds. While this might have been the norm for the occasional task, working with such ad hoc arrangements over a full work week produced considerable discomfort.

Individual factors

Individual differences: Interestingly, WFH gave participants insight into how certain personality traits affected their experience. Those who preferred working alone and resented distractions found that WFH suited them well. Those who valued autonomy, for example, the freedom to decide when to work, schedule tasks, and take breaks, enjoyed these opportunities during lockdown. Those acknowledging or implying that they had extroverted personalities, or those who simply appreciated teamwork and communication with others, found they could not operate as productively when WFH as when they were onsite.

Household composition: For those living with partners, caring for children, and supporting online schooling, productivity depended on the nature of family dynamics and how much time they had for work activities. There were some responses that combined positive and negative aspects of the same issue. For example, one participant observed: ‘I love working from home in normal circumstances but do struggle a bit with the whole family here, as we all have very different work styles.’ Gender effects also surfaced, with some women, but very few men, remarking how they had to carry a full workload while taking on a disproportionate share of childcare and other home responsibilities. Those living alone reported a sense of loneliness and alienation, to some degree mitigated by online work meetings, both operational and social.

Work–life balance/work–life conflict: Many enjoyed the extra time they had in lockdown, avoiding ‘the dreaded commute,’ and spending more time with family or on personal activities, such as exercise and relaxation. Some participants claimed that the extra time led to higher work productivity. However, for others, lockdown undermined their performance; they had too little time due to household responsibilities, frequent interruptions, and noise. For some, this meant working late to complete their tasks or feeling obliged to be available, even after regular hours. Some living alone found they were spending excessive time on the job because they had little else to do that constituted ‘life.’

Wellbeing

We identified equivalent categories impacting employee wellbeing as were apparent for employee performance (Table 2).

Organizational factors

Leadership and communication: Various forms of communication from the company and team leaders alleviated employee uncertainty and anxiety. For employees at company B, reassurance that there would be no redundancies provided them with a greater sense of security. The main communication problems workers encountered related to the frustration of poor internet connections, ‘Zoom fatigue’ and the lack of social contact, particularly for those living alone.

Teamwork and collaboration: Some participants were impressed with how supportive and collaborative their teams had become. What may have been taken for granted in the office now had a greater sense of meaning. Sharing common challenges provided affirmation that one was not alone in struggling to cope, operationally and psychologically. Nevertheless, some acutely felt a loss of teamwork or were reluctant to participate in online meetings. Others lamented the inability to collaborate as productively and enjoyably as they had in face-to-face settings.

Autonomy and trust: The relative freedom to manage one's work schedule was appreciated, partly because it reinforced feelings of self-efficacy and partly because it reduced the pressure of deadlines. In contrast, those who felt they were not trusted, or lacked trust in others to reply to communications or manage their workloads, reported negative emotions, such as frustration.

Support: Some employees appreciated their company's attention to staff wellbeing, finding that such emotional support, along with the operational or instrumental support they had received, helped them cope. Other employees had more cynical attitudes that the organization or team leader had not cared sufficiently about them, exacerbating their stress levels.

Performance expectations: Many participants were comforted by knowing that the organization was aware of how difficult it was to perform at prior levels; it took the pressure off them to work longer hours. Conversely, some expressed bitterness that their personal circumstances had not been considered, or that higher than average work outputs were expected. For instance, there was ‘an expectation that you would always be on the tools, even at like 9/10 p.m., as what else would you be doing in lockdown?’

Furniture and technology factors

Capability: Given that furniture and technology are key elements of home workspaces that enable productivity, several participants experienced wellbeing when performing to expected levels, despite their circumstances. However, those with unsuitable resources and internet problems were either frustrated with delays or stressed that they were unable to perform to the level they or others expected.

Comfort: Physical comfort contributes to wellbeing, sometimes unconsciously, whereas discomfort undermines it. Participants appreciated the ability to enjoy fresh air, sunshine, and temperature control compared to air-conditioned office environments. Contrastingly, the pain some felt from sitting for long hours on unsuitable chairs or peering at small screens translated into unhappiness with WFH.

Individual factors

Individual differences: WFH during a pandemic provided challenges on several levels. Some participants explicitly observed how certain personality traits, such as introversion, made WFH a pleasing option for them; conversely, those who liked engaging with others at work reported a sense of disengagement, alienation, or loneliness. Values, such as the desire for fairness, led to some feeling they had been treated decently by their employers, while others were critical of heavier workloads and lack of perceived support. Some women carrying a heavier workload at home expressed irritation with their male partners.

Household composition: WFH in a crowded house with all household members almost constantly at home was a boon for some, but for others it created too much distraction from work and frustration from being unable to escape from other people. Also, as mentioned previously, some found the loneliness of living and working alone distressing.

Work–life balance/work–life conflict: The construct of work–life balance is often taken as a desirable feature of WFH. In line with this, some participants enjoyed the opportunity to spend more time on ‘life’ and less on work and commuting; these provided a silver lining to both lockdown and its concomitant anxiety. Others found that the extra home responsibilities and the inability to switch off from work, given its constant presence, were a cause of concern and resentment.

Discussion

The findings reveal the many factors that impacted employees' performance and wellbeing in two service companies WFH during New Zealand's first national lockdown, lasting nearly 2 months. We discuss our findings according to the aggregate dimensions and second-order themes regarding the interface between demands and resources, as depicted in Figures 2 and 3 and in Tables 1 and 2. Many of the job demands that were experienced pre-pandemic both in the office and WFH, such as high workload, were exacerbated under lockdown conditions. Some participants benefitted from the extra resources provided, such as multiple devices and emotional support, while others struggled to cope with inadequate resources.

Organizational factors

Importantly, while our findings reveal a range of factors influencing participants' performance and wellbeing, most comments were about positive aspects of work. In terms of resources, good leadership and communication with employees (especially during a pandemic or another crisis) help employees cope with challenging circumstances (Amis & Janz, Reference Amis and Janz2020). Sanders, Nguyen, Bouckenooghe, Rafferty, and Schwarz (Reference Sanders, Nguyen, Bouckenooghe, Rafferty and Schwarz2020: 291) advise that, to be effective, ‘messages are perceived as distinctive, consistent, and consensual.’ Most participants in both companies in the current study valued the content and tone of corporate and managerial communication, although there was some criticism. Previous studies have shown the value of support (instrumental, emotional, and informational), to employees experiencing organizational change (Smollan & Morrison, Reference Smollan and Morrison2019), and to those WFH (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Teo, Tan, Bosua and Gloet2016). Many of our participants appreciated how their companies had shown a strong concern for them and sought to provide them with the support to help them perform. In lockdown, support becomes even more important in facilitating performance and reducing anxiety (Malinen, Wong, & Naswall, Reference Malinen, Wong and Naswall2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Qian and Parker2021). Waizenegger et al. (Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020: 6) use the construct of affordances, which has both functional and social dimensions, to explain how, during lockdown, information technology led to what was ‘on the one hand, an enabler for team collaboration, but on the other hand led to increased role conflict, blurring of work-life boundaries, and virtual meeting fatigue.’ Communication, teamwork, and autonomy can be resources for those WFH (Cooper & Kurland, Reference Cooper and Kurland2002; Van Dyne, Kossek, & Lobel, Reference Van Dyne, Kossek and Lobel2007), and, during lockdown, impact more widely on performance and wellbeing (Anicich et al., Reference Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale and Scherer2020; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas and Rolls2021).

Furniture and technology factors

Suitable furniture and technology were resources that enabled performance and bolstered wellbeing. These resources were supplied partly by the companies (to a much greater extent than pre-lockdown), and partly by the employees, thereby crossing the boundaries of organizational and individual factors. However, many participants found WFH was quite literally a pain, referring to physical ailments such as backache and headaches (e.g., Davis et al., Reference Davis, Kotowski, Daniel, Gerdsing, Naylor and Syck2020; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas and Rolls2021). Inadequate workstations may be acceptable for short stints of WFH but, when used all day and for weeks on end, cause decreased comfort and wellbeing. Those living in areas prone to connectivity problems experienced limited ability to join online meetings, poor meeting sound quality, and trouble with online file access. Despite the attempts of the ICT departments of both companies to provide the necessary support, weaknesses in the technical affordances of ICT (Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020) led to a reduced capability to perform and growing frustration and anxiety.

Individual factors

Both performance and wellbeing are partly influenced by individual differences, particularly personality (Bakker, Reference Bakker2015; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hetland, Olsen and Espevik2019; Sonnentag, Reference Sonnentag2015). Research into WFH before the pandemic indicated how certain traits could be considered resources, facilitating workers' productivity and reducing stress. For example, Anderson, Kaplan, and Vega (Reference Anderson, Kaplan and Vega2015) reported that teleworkers with higher openness to experience reported greater wellbeing compared with office workers, indicating that openness to experience acted as a resource. Our study found mixed results; in terms of wellbeing, some participants were proud that certain personality traits had helped them to adapt well, whereas others reported excessive rumination, which may have been caused by overwork and anxiety over the virus.

Remote work requires employees to be relatively self-sufficient and autonomous (Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023; Malinen, Wong, & Naswall, Reference Malinen, Wong and Naswall2020). In research on blended working arrangements pre-COVID-19, Wörtler, Van Yperen, and Barelds (Reference Wörtler, Van Yperen and Barelds2021) found that autonomy orientation led to positive attitudes toward the organization. The salience of autonomy was evident in the comments of some of our participants, who either appreciated or criticized the degree of autonomy they were given in lockdown. Those who valued autonomy experienced an improved fit either between their actual work and work preferences (person-job fit) or between their actual autonomy and need for autonomy (needs-supplies fit) (Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023). Some participants suggested that their introverted personalities contributed to psychological comfort while WFH, while the extroverted missed the social contact in the office. Similarly, relative isolation and working alone would have suited those who were comparatively introverted but may have negatively impacted their more extroverted and social peers (person–job fit) (Cooper-Thomas & Wright, Reference Cooper-Thomas and Wright2013). The additional support and care experienced by many of the respondents in this study would have likely added to person–organization fit perceptions – highlighting the shared focus on employee wellbeing during the pandemic and the associated stressors experienced by workers and the wider community.

Being ‘in touch and emotionally connected to individuals outside of one's job’ (Anderson, Kaplan, & Vega, Reference Anderson, Kaplan and Vega2015: 886) helped those who enjoyed extra social time at home during lockdown. However, most people in lockdown were denied both collegial, onsite workplace connections and those outside of work – other than those by telephone or web-based media. Those who lived alone felt especially disconnected. Isolation and loneliness are demands of WFH (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Teo, Tan, Bosua and Gloet2016; Cooper & Kurland, Reference Cooper and Kurland2002; Golden, Veiga, & Dino, Reference Golden, Veiga and Dino2008) that were exacerbated for some workers during COVID-19 (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Qian and Parker2021; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas and Rolls2021). This disconnection curtailed social interaction and participation in entertainment, hospitality, sport, religion, and community events.

A model of WFH during lockdown

We used JD-R theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017) to elaborate on prior understandings of WFH. Our research question relates to the factors that impact employee performance and wellbeing during lockdown and how they might be demands or resources. Our data structure, shown in Figure 2, indicates 10 factors of importance, grouped under the aggregate dimensions of organizational factors, individual factors, and a blend of the two in the form of furniture and technology factors. Figure 3 provides our model of key job demands and resources while working from home during lockdown. While demands and resources have some degree of match, realistically they are not simply parallel concepts because one demand could be addressed by several resources, and several demands could be mitigated by one resource.

Our findings demonstrate a range of factors occurring during WFH and impacting employee performance and wellbeing. While our research echoes other findings in New Zealand (Franken et al., Reference Franken, Bentley, Shafaei, Farr-Wharton, Ommis and Omari2021; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Hoek, Jenkin, Gendall, Stanley, Beaglehole and Every-Palmer2020; Malinen, Wong, & Naswall, Reference Malinen, Wong and Naswall2020, Sibley et al., Reference Sibley, Greaves, Satherley, Wilson, Overall, Lee and Barlow2020), and in other countries (e.g., Anicich et al., Reference Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale and Scherer2020; Trougakos, Chawla, & McCarthy, Reference Trougakos, Chawla and McCarthy2020; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Becerik-Gerber, Lucas and Rolls2021), we have identified a unique combination of individual and organizational factors that present as demands and resources that influence employee perceptions of the outcomes of enforced WFH. Our findings show that the personal costs and benefits of WFH during lockdown are impacted by the wider environmental conditions of a deadly disease, and its material and psychological impact on work and home life, and on other social connections people have lost for long periods.

Limitations and implications for research

The first limitation of our study is that data were gathered in two New Zealand companies after a relatively short (but extreme) lockdown ended (approximately 2 months). This may limit the wider application of our findings since employees in many other countries experienced longer lockdowns. The situation in New Zealand in 2020 was much less severe than many other countries, with fewer COVID-19-related cases and deaths due to geographic isolation and early government action with wide community support. The second limitation is that data were gathered at one point in time and do not reflect potential temporal changes in employees' experiences. On the one hand, people and organizations are likely to adapt over time, increasing resources and thus meeting some demands; on the other hand, some demands may accumulate over time. A third limitation is that qualitative survey data leave no opportunity to probe more deeply than would be possible in interviews or focus groups. Despite that, we gathered many insights into the experience of WFH while in lockdown.

Our study opens many other avenues for exploration. Areas for future research include the effects of corporate and team communications, online meetings, trust, concern for wellbeing, and clarification of performance expectations. One promising approach would be a longitudinal investigation of employee experiences of WFH from different contexts, examining the influence of the length of lockdowns, the number of lockdowns, and the changing health, administrative, and community conditions in different geographic areas. This would help to separate the similar costs and benefits to them, for example, isolation and the absence of commuting, from those that are specific to involuntary WFH (Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023).

With many employees experiencing a series of lockdowns, research is needed as to whether prior experience is a help or a hindrance. As events unfold and lockdown periods are ended, extended, or reintroduced, performance and wellbeing may either increase through sound employer actions or decrease if organizational measures and a can-do culture fade away, challenging employee resilience and goodwill. While the negative effects of ‘Zoom fatigue’ (Fosslein & Duffy, Reference Fosslein and Duffy2020) have been well-documented (e.g., Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020), and can be mitigated by group belongingness (Bennett, Campion, Keeler, & Keener, Reference Bennett, Campion, Keeler and Keener2021), the outcomes of this for those WFH for long periods need exploration. Relatedly, the suddenness of the change to WFH differs from most change research which typically examines planned, episodic change (Brazzale, Cooper-Thomas, Haar, & Smollan, Reference Brazzale, Cooper-Thomas, Haar and Smollan2022). Thus, although employees have to acclimatize to constant organizational change, research is needed into the consequences of abrupt and ongoing change.

Other issues for future pandemic research of WFH include workload, productivity, and employee monitoring. In line with other reports (e.g., Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a), our data suggested that for some employees, continuing with heavy workloads while WFH long-term would be harmful to mental health, and early productivity gains would be lost. Performance monitoring was also an issue; while this might be done informally in an office environment (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Zhu, Campion and Alonso2020), when done remotely, it has been criticized as a pernicious form of surveillance (Hern, Reference Hern2020). While employees may accept and even appreciate monitoring of some issues, such as wellbeing and the ergonomics of their home workspaces, monitoring productivity in constrained conditions that hamper employees' productivity will be unwelcome.

More research needs to investigate how workspaces, furniture, and technology influence performance and wellbeing for teleworkers (Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020), and how they might be perceived by employees as demands or resources. Our study clearly shows that while some of our participants were comfortable and productive in their homes, others suffered physically and psychologically from inadequate working conditions (see also Davis et al., Reference Davis, Kotowski, Daniel, Gerdsing, Naylor and Syck2020). Another fruitful area for investigation is how requirements for employees to self-fund the capital and operating expenses of WFH impact their perceptions of WFH (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Zhu, Campion and Alonso2020).

Regarding individual differences, there is a need for an in-depth examination of anxiety and other manifestations of stress, acknowledging both work demands and the temporary fractures to work-based and other relationships caused by the inability to meet in person or attend gatherings. Our participants noted extroversion and introversion as important traits influencing their reaction to WFH. Anicich et al. (Reference Anicich, Foulk, Osborne, Gale and Scherer2020) found that people who were lower in neuroticism adjusted more rapidly to the realities of the pandemic. Park and DeFrank (Reference Park and DeFrank2018) demonstrated the value of proactivity in coping with stress. Other facets of personality, such as openness to experience, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience (Anderson, Kaplan, & Vega, Reference Anderson, Kaplan and Vega2015; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hetland, Olsen and Espevik2019), may also influence employees' responses to government-mandated WFH. While there has already been considerable evidence of WFH causing social isolation and loneliness during lockdown (Brooks, Reference Brooks2021; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Waizenegger et al., Reference Waizenegger, McKenna, Cai and Bendz2020), future research needs to investigate the differences between the new era and pre-pandemic studies of WFH (e.g., Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Teo, Tan, Bosua and Gloet2016; Charalampous et al., Reference Charalampous, Grant, Tramontano and Michailidis2019; Cooper and Kurland, Reference Cooper and Kurland2002).

Past research on flexible work arrangements has found benefits for work–life balance (e.g., Delanoeije & Verbruggen, Reference Delanoeije and Verbruggen2020; Grant, Wallace, & Spurgeon, Reference Grant, Wallace and Spurgeon2013; Maruyama, Hopkinson, & James, Reference Maruyama, Hopkinson and James2009). However, what has scarcely been researched is the impact of the whole household being at home for extended periods of time in lockdown, and to what extent this may have generated work–life conflict rather than balance (Koslowski, Linehan, & Tietze, Reference Koslowski, Linehan and Tietze2019; Lopes et al., Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023). Felstead and Reuschke (Reference Felstead and Reuschke2020) also suggest that work–life balance benefits in normal times tend to level off as the frequency of days at home increases. Furthermore, they found that after 3 months of lockdown in the UK the benefits of work–life balance for many had been eroded by lower wellbeing.

Person–environment fit (Cable & DeRue, Reference Cable and DeRue2002; Cable & Judge, Reference Cable and Judge1996; Caplan, Reference Caplan1987; Cooper-Thomas & Wright, Reference Cooper-Thomas and Wright2013) is another construct that might provide a useful lens for investigating WFH in lockdown or post-lockdown times. The more widely experienced benefits of WFH since the advent of the pandemic have led to a heightened desire to avoid the commute and office environment, despite organizational instructions or requests to return to the office (Tsipursky, Reference Tsipursky2022). Experiencing a poor fit to elements of work can add demand to the experience of work and has been shown to relate to a variety of wellbeing outcomes, and a key factor, according to the study by Lopes et al. (Reference Lopes, Dias, Sabino, Cesario and Peixoto2023), is whether WFH is voluntary or involuntary.

Implications for practice

Many organizations were unprepared when lockdown was first imposed, even after weeks or months of news of COVID-19. To plan for future WFH under emergency conditions, managers need to be aware of several key factors. First, they need to know whether their employees are sufficiently well-equipped in terms of furniture and technology, then consider taking adequate steps to resource any shortfall, as was done to some extent by the two organizations in our study. Employee performance and wellbeing are negatively impacted when WFH is not adequately resourced (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Kotowski, Daniel, Gerdsing, Naylor and Syck2020). Second, managers need to establish policies and routines for lockdowns (and other crises requiring WFH) that support communicating work expectations, allocating tasks, and setting guidelines for online meetings and returning to the office (Semuels, Reference Semuels2020b; Tsipursky, Reference Tsipursky2022). Third, attention must be paid to wellbeing and support – instrumental, emotional, and informational (Smollan & Morrison, Reference Smollan and Morrison2019) – on an ongoing basis for those employees WFH. Support was a noticeable feature in our study, which was triggered by requests from the two participating companies as ways of assessing how helpful their interventions had been. This becomes especially important as organizations need to change, partly as a result of the pandemic (Amis & Janz, Reference Amis and Janz2020) but also as they evolve in other ways, particularly when hybrid arrangements and permanent WFH are becoming more commonplace (Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development [CIPD], 2020a; Wörtler, Van Yperen, & Barelds, Reference Wörtler, Van Yperen and Barelds2021; Tsipursky, Reference Tsipursky2022). Leaders do have capacity to reduce demands and provide valued resources.

Conclusions

We employed JD-R theory to investigate employee perspectives of enforced WFH, anticipating that this would differ in the COVID-19 era from previous, more benign times. From qualitative comments gathered from employees in two New Zealand organizations, we identified a range of demands and resources outcomes. The impact of these on employees' performance and wellbeing depended on many factors, varying from the organizational to the individual, and the intersection of the two in the form of furniture and technology. Our findings add to the growing literature of employee experiences of COVID-19 by showing that employees compelled to WFH can achieve performance and experience wellbeing if they are faced with manageable demands and suitable resources to meet them. It has also shown how resilient, adaptable, innovative, and compassionate employees and employers can be in the face of adversity.