Our research examines the role of humour in power-differentiated wage bargaining conversations between company management on one side and a labour union on the other. We start this article with a brief overview of the dynamics of power relations in negotiations and how humour is utilised by unequal parties in interactions. We then argue why the lens of conversation analysis is particularly useful in examining how humour emerges and shapes the dynamics of power-differentiated wage bargaining conversations.

Negotiations and Power Relations

In negotiations such as wage bargaining, parties not only strive to get the most of the scarce resource (Thompson, Reference Thompson2000), but also endeavour to reach a mutual agreement (Carnevale & Pruitt, Reference Carnevale and Pruitt1992) on how resources may be allocated. Negotiations tend to mix both cooperative and competitive stances (Bonaiuto, Castellana, & Pierro, Reference Bonaiuto, Castellana and Pierro2003) as both parties consider common interests and points of conflict (Harbison & Coleman, Reference Harbison and Coleman1951).

Negotiation allows for the exchange of information, arguments, and strategic manoeuvres (Jensen, Reference Jensen2009). During conversations, one party articulates an opinion and the other party may align or misalign with this position (Arminen, Reference Arminen2005). Hence, each party has to be certain of what it wants and then chooses what it deems is the best way to frame its arguments and counter-arguments (Alavoine, Reference Alavoine2012), bearing in mind the other party's tactical capacity and then making certain that it gets a positive response from that other party in the end (Wheeler, Reference Wheeler2002).

Historically, industrial negotiations were introduced to democratise what used to be autarchic decision-making by management (Cordova, Reference Cordova, Blanpain and Baker1990). Collective bargaining thus turned into a space where both management and labour could decide jointly and share rule-making capacity (Duvall, Reference Duvall2009).

Power at the collective bargaining table, however, is rarely distributed evenly (Alavoine, Reference Alavoine2012). We define power as the likelihood of being able to carry one's will despite opposition (Weber, Reference Weber1947), the potential to shape other people's behaviours and thoughts (Norrick & Spitz, Reference Norrick and Spitz2008), and control over resources (Pruitt & Carnevale, Reference Pruitt and Carnevale1993). The party that is less dependent on its counterpart generally has more power at the bargaining table (Wolf & McGinn, Reference Wolf and McGinn2005).

Asymmetries in power affect the process of negotiation (Daoudy, Reference Daoudy2009). The party with greater power is usually the one who is able to gain more from the negotiation (Kim, Pinkley, & Fragale, Reference Kim, Pinkley and Fragale2005). The more powerful party has greater capacity to manipulate (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Pinkley and Fragale2005) and put itself in a more advantageous position over the less powerful party. As such, when power relations are unequal, the one who has greater power can more easily get what it wants and address its interests during negotiations (Wolf & McGinn, Reference Wolf and McGinn2005).

Humour in Power-Differentiated Interactions

Various researchers have investigated the utility of humour in asymmetric interactions. An integrative review of the literature on power-differentiated negotiations shows that humour functions as a mechanism of control, a strategy to subvert power, and a tool to maintain solidarity.

Humour as a mechanism of control. Humour has been used to compel people to adhere to or abide by certain patterns of behaviour as well as to behave as requested (Martin, Reference Martin2006); for instance, teasing or joking to make another do as instructed, or to emphasise a particular deviant behaviour (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000; Meyer, Reference Meyer2000). Humour may also be used to convey approval and disapproval (Stephenson, Reference Stephenson1951), or as a means of disciplining colleagues perceived to be slackening off (Collinson, Reference Colinson1988). One, then, is subtly steered into conforming to the tacit directive or the implicit norm by the use of humour (Martin, Reference Martin2006; O’Quin & Aronoff, Reference O’Quin and Aronoff1981).

In power-differentiated interactions, use of humour to exert control is usually associated with the more powerful than the less powerful. For instance, Norrick and Spitz (Reference Norrick and Spitz2008) found that conflict may be resolved using humour when it is presented by the party who wields more power. Rogerson-Revell (Reference Rogerson-Revell2007) likewise reported that style-shifting in business negotiations is a tactic commonly used by high-status speakers. Style-shifting makes the other interlocutors uncertain as to how they should respond, as well as strengthens the speaker's authority to introduce change in an interactive way. Even the use of mockery by the more dominant during negotiations can influence the action or suppress the undesired behaviour of the less dominant (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Banas, Rodriguez, Liu and Abra2012). In these instances, the more powerful party uses humour to exert control over the discussion and comportment of the less powerful. Martin (Reference Martin2006) deemed that the use of humour to impose certain forms of conduct (e.g., social norms) or take control of the situation reinforces one's dominance in a group hierarchy.

Even though the use of humour as a means of exerting control is closely linked with the more dominant group, the less dominant one may also utilise humour to influence the behaviour of the more powerful. For instance, it may use humour as an ingratiation tactic to garner favours or approval from those who have more power (Martin, Reference Martin2006). In this way, the less powerful is able to persuade the more powerful.

Humour can also be an effective way of ‘doing power’. Employing humour in framing arguments, such as in negotiations, can attack the position or version of reality of the opposing party (Bonaiuto, Castellana, & Pierro, Reference Bonaiuto, Castellana and Pierro2003) and delegitimise its claim (Maemura & Horita, Reference Maemura and Horita2012). If carried out in a less explicit manner, employing humour can be a subtle strategy in communicating messages about power relations and getting things done at the same time (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000). Here, doing power may be performed by the more dominant by making fun of the less dominant during the course of the negotiation. In other instances, the more powerful side may use humour to subtly gain control of the whole negotiation process. Humour, as used here, camouflages the authoritative nature of the message (Martin, Reference Martin2006), yet also calls attention to who is in charge, as well as keeps the situation under control. Thus, during wage bargaining interactions, management may do power by making fun of the inadequacies of the workers or by shrewdly pointing out management authority in a playful manner.

This tells us that effectual use of humour influences people in various ways (Martin, Reference Martin2006). As such, humour may be used either in a positive or negative manner in negotiation practices. At the wage bargaining table, for instance, humour may be utilised to manage the interaction and thwart discussion about wages (Maemura & Horita, Reference Maemura and Horita2012), or to manipulate the conversation to obtain a better deal.

Humour as a strategy to subvert authority. While humour may be employed by the dominant to exert control, it may be used by the less dominant to challenge authority in a more socially acceptable way (Holmes & Marra, Reference Holmes and Marra2002). Another function of humour, as used in asymmetric interactions, is thus to provide the powerless with an avenue to challenge the hegemony of the powerful or the existing relations within the power structure (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000). Here, humour provides the less dominant with a discursive means of expressing opposition, protest, defiance, dissatisfaction, and recalcitrant and outrageous ideas in a non-threatening way (Holmes & Marra, Reference Holmes and Marra2002; Martin, Reference Martin2006). It also helps the less dominant to articulate their criticisms and to contest the status of the more influential (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Banas, Rodriguez, Liu and Abra2012). These uses of humour can be construed as the less dominant's version of doing power in conversations. For instance, in their study of humour in the workplace, Taylor and Bain (Reference Taylor and Bain2003) found that labour unions’ use of humour is essentially instrumental in enfeebling management authority during instances of employer hostility. Colinson (Reference Colinson1988) likewise found that humour shared among shop-floor workers of a truck factory in England, besides being a means of finding fun and releasing tension, is also a way for them to express their antagonism and resistance towards management.

Humour used to subvert authority may also mean using it to artfully achieve the goal of the less powerful in the interaction, while de-emphasising the power gap (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000). For instance, in trying to bargain with administration, workers may jokingly bemoan their poor working condition or express the shortcomings of management (Martin, Reference Martin2006). Here, the underdogs may utilise humour to articulate their thoughts, face up to authority, and shift the power symmetry.

In conversations, conveying strong arguments that are swathed in humour bring about less adverse effects because they are expressed in a lighthearted fashion (Romero & Cruthirds, Reference Romero and Cruthirds2006). It is also not easy for a superior to dispute subversive humour as it could lead to embarrassment (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000). This makes humour an effective device for the powerless to subvert overt authority. Humour used this way has been given various labels by different researchers. Holmes (Reference Holmes2000) called it contestive humour whereas Holmes and Marra (Reference Holmes and Marra2002) termed it subversive humour. Dunbar and colleagues (Reference Dunbar, Banas, Rodriguez, Liu and Abra2012), on the other hand, dubbed it rebellious humour, while Romero and Cruthirds (Reference Romero and Cruthirds2006) labelled it mild aggressive humour.

Humour as a tool to create and maintain solidarity. Humour plays an important role in group dynamics (Romero & Pearson, Reference Romero and Pearson2004). It lessens hostility and enhances in-group bonding and collegiality (Cooper, Reference Cooper2008; Forester, Reference Forester2004; Holmes, Reference Holmes2000; Reference Holmes2006; Martin, Reference Martin2006; Vuorela, Reference Vuorela2005). This is true even in interactions between asymmetric parties. Romero and Cruthirds (Reference Romero and Cruthirds2006) argued that humour is valuable for management in enhancing group cohesiveness in the workplace, and there are studies that appear to support this claim. For instance, Tang (Reference Tang2008) found that use of humour by management of Taiwan manufacturing firms in dealing with their employees significantly contributed to the solidarity of the group. Mesmer-Magnus and Glew (Reference Mesmer-Magnus and Glew2012) also reported that managements’ use of humour in handling workers is associated with reduced work withdrawal and enhanced workgroup unity. Martin, Rich, and Gayle (Reference Martin, Rich and Gayle2004) thus concluded that humour is vital to an organisation's collective organisational climate. It can create the kind of cohesiveness and relational trust between management and workers that underpin the latter's willingness to go beyond what their job description requires.

Creating and maintaining solidarity also means engendering a ‘we feeling’ among interactants. Humour shared by two parties conveys the message that both have something in common (Lipovsky, Reference Lipovsky2012; Martin, Reference Martin2006) or that one is part of the group (Meyer, Reference Meyer2000). This leads to feelings of affiliation (Lipovsky, Reference Lipovsky2012) and identification with the other speaker or party and results in reduced tension (Meyer, Reference Meyer2000), especially during a heated discussion (Martin, Reference Martin2006). Thus, jokes shared during wage bargaining interactions may highlight both parties’ shared values and give rise to feelings of affinity towards each other, thereby lessening the pervading friction and hostility.

The literature presented above demonstrates the existence of power relations in negotiations and the utility of humour in asymmetric interactions. However, there is a dearth of literature that looks at how humour shapes the dynamics of power-differentiated negotiations. More so, this concept is yet to be examined in the context of bargaining that involves naturalistic intergroup conversations on highly contested resource such as wages. Thus, this research sought to answer the following questions:

1. What functions of humour emerge in power-differentiated wage negotiations?

2. How does humour shape the dynamics of power differentiated wage bargaining that concluded in an agreement?

In this article, we present conversation analysis as a fitting approach to examine how humour emerges and shapes the dynamics of power-differentiated wage negotiations.

Conversation Analysis: Talking as Doing

Engaging in interactions is one of the ways by which we strategically achieve goals (Wooffitt, Reference Wooffitt2005) such as desired gains in negotiation. As an approach to understanding how people manage their interaction with others, conversation analysis examines in detail how people co-construct realities, such as what is an acceptable way of allocating scarce resources, through talk-in-interaction (Grancea, Reference Grancea2007).

Conversation analysis assumes that talk or utterances do not merely state things but do things (Pomerantz & Fehr, Reference Pomerantz, Fehr and van Dikj1997; Wilkinson & Kitzinger, Reference Wilkinson, Kitzinger, Harré and Moghaddam2003). As such, how conversation is locally managed by interlocutors may show how power operates and is used as a resource in interactions (Hutchby, Reference Hutchby1996).

Conversations are characterised by having a structure composed of the participants’ successive utterances that can be construed as a series of action. What we say and how we say it invites succeeding actions or limits the range of actions that may follow (Wooffitt, Reference Wooffitt2005). The conversation structure demonstrates how people achieve orderly interactions (Wooffitt, Reference Wooffitt2005). Conversation analysts assume that orderliness is produced by the participants’ tendency to design their talk according to how they want it to be understood by its intended recipient (concept of recipient design). Thus, conversation analysis gives importance not just to what is being said but also to how and when utterances are expressed (Liddicoat, Reference Liddicoat2007; ten Have, Reference ten Have1999; Wooffitt, Reference Wooffitt2005). Locating conversation structures where humourous talk or laughter occurs in asymmetric wage bargaining interactions enables one to determine how humour shaped the dynamics of the negotiation.

Examining turn-taking, sequence, and turn-construction/design are usual ways of analysing the interactional organisation of talk (ten Have, Reference ten Have1999). Sequence organisation has been mostly used in negotiation studies (Arminen, Reference Arminen2005; Maynard, Reference Maynard2010) and research on humour and/or laughter in conversations (Glenn, Reference Glenn1989; Jefferson, Reference Jefferson and Psathas1979; Kangasharju, & Nikko, Reference Kangasharju and Nikko2009).

Utterance sequence may show how engaging in humourous talk and conversational laughter help achieve wage bargaining agreement in this power-differentiated negotiation.

More specifically, analysing the occurrence of humour through humourous talk and laughter in intergroup conversations between labour and management may reveal if and how these establish control, subvert overt authority or maintain solidarity, as it invites or limits succeeding talk or action.

Method

The Data: Wage Bargaining Conversations

Conversations pertaining to wage increases are usually embedded in collective negotiations between management representatives and labour union. The data used for the study were wage bargaining conversations in a multinational beverage company operating in the Philippines. The negotiation occurred from March to July 2010 between the management and the local labour union, representing all regular rank-and-file non-sales employees in Metro Manila and its nearby provinces in the south. The labour union is informally affiliated to the most progressive and militant labour federation in the country. Although there is an active Labour-Management Council in the company, the union members have engaged and continuously participate in mass actions inside and outside of the company premises to express their dissatisfaction or disagreement with company/government policies or initiatives.

All negotiators were Filipinos. The negotiation data analysed in this research was an attempt to create a new Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) by the expiration of the 2007–2010 agreement.

Recorded proceedings of collective bargaining conversations are highly confidential and must be used only with the mutual consent of both parties. Thus, consent to use the data for research and identify the company in the manuscript was sought from and granted by the Union President and the company's Senior Human Resources (HR) Manager.

Table 1 shows the list of negotiators and their ascribed role in wage bargaining. Code names were used to protect the identity of the people involved in the negotiation.

Table 1 Code Names and Formal Roles of Negotiators

Transcribing, Selecting, and Coding Wage Conversations

The entire collective bargaining meetings were recorded through the union vice president's laptop at first and then with the aid of a digital recorder that we provided. Recording the bargaining meeting for minute-taking is a common practice in collective negotiations in the Philippines (Edralin, Reference Edralin2003), so having the recorder remained unobtrusive to the bargaining process. A research assistant did the orthographic transcription of the bargaining proceedings.

We then lifted all conversations that pertained to wage rates and re-transcribed according to how the words were spoken. Of the 17 meetings, 9 had conversations about wages. After determining the conversation extracts, we then applied the transcription symbols developed by Jefferson (Reference Jefferson and Psathas1979; see Appendix), which are commonly used in conversation analytic research (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, Reference Wilkinson, Kitzinger, Harré and Moghaddam2003; Wooffitt, Reference Wooffitt2005). The data were subjected to three rounds of review, with the help of another research assistant who was trained to apply the notation symbols to make sure that all conversation details were captured in the transcripts.

We then selected conversation sequences with instances of humour. We obtained 74 conversation sequences that were given numerical and letter codes to represent the date of the wage bargaining meeting and the temporal occurrence of the conversation in the meeting respectively (e.g., 1A, 1B, 2A).

Procedure for Data Analysis

To analyse our data, we employed the framework developed by Pomerantz and Fehr (Reference Pomerantz, Fehr and van Dikj1997) for conversation analysis but further tweaked it to fit the process of selecting and analysing conversation sequence with instances of humour. We described instances of humour as ‘utterances which are identified by the analyst . . . as intended by the speaker(s) to be amusing and perceived to be amusing by at least some participants’ (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000, p. 163). Although laughter was an obvious clue for an occurrence of humour in conversations, other instances were identified through the tone of voice of the speaker as well as the manner of response of the recipient of talk (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000).

After selecting a sequence with instances of humour within wage conversations, we examined the actions in the sequence by determining how humourous conversations shaped the utterances of participants in a specific turn and in each succeeding turns. The third step focused on how speakers designed their talk and succeeding actions to ensure understanding of the actions and the subject of the talk. The design determined the options made available to the recipient by the preceding utterance. Finally, we examined how the actions were achieved through humourous conversations that invoked roles and/or relationships among the people involved in the conversations. The last two steps allowed us to examine the dynamics of the power relations in negotiations and to determine the utility of humour in these asymmetric naturalistic interactions.

To enhance reliability of the analysis, two of the authors independently coded and analysed the data. We then conducted inter-coder discussions until agreements were achieved.

Results

Analysis of our data revealed how labour and management utilised humour to institute control over their interactions, undermine authority, and uphold intergroup camaraderie in the bargaining table. Results also point to how the use of humour facilitated agreement in power-differentiated wage negotiation.

Management Controlling Tensions and Deadlocks Through Humour

Management used humour to lessen the tension and break free of an impasse at the bargaining table. An example of how management used humour to manoeuvre the course of the discussion was when the parties were negotiating for the rate of wage increase in Extract 2S.

Extract 2S:

In line 5, L3 told M1 that management's proposed increase (lines 1 through 4) would anger the workers and lead them to hold a demonstration. In the next turn, M2 replied by deliberately misinterpreting the word pikit (mispronounced picket), taking it to mean pikit (eyes closed in Filipino). With the simultaneous laughter in line 8, labour showed that it understood the joke. We can see here how management employed humour to take control of the situation primarily by using style-shifting as a tactic to reduce the building tension. Humour was also utilised by management to disentangle themselves out of a deadlock. The following excerpt, where management and labour discussed the possible amount of incentives for the employees, shows this.

Extract 6C:

In lines 1 through 14, labour and management were engaged in a holdup with not one party willing to compromise. In lines 15 to 16, M suddenly made a comment that the incentives are mere decorations, which allowed M1 to change topics by saying before I forget, to which L3 reacted by laughing in the next turn, making the other interlocutors laugh as well. Here, management applied humour to break a gridlock, as well as switch the mood of the conversation into something that is less heated.

Management also used humour to assert its authority over labour and imperceptibly draw attention to who was in charge. This can be seen in Extract 6B below.

Extract 6B:

Lines 1 through 20 present the exchanges between labour and management as they tried to haggle for the employee wage increase. In line 21, M1 put a halt to the interchange by saying that they had reached the bargaining limit. His ‘kahit saan pa kayo umakyat’ (no matter where you go up), even if said in a lighthearted manner, pointed to management as the one in authority and in charge of the negotiation process.

Humour as Labour's Means to Defy Authority

Labour used humour to express the voice of the underdog and challenge the power of authority. Its application of humour helped labour state its demands, legitimise its bargaining position, delegitimise and refuse management's offer, as well as express doubt on management's sincerity. Labour was also able to draw on humour to actually threaten management.

Extract 6K:

The above extract is an example of how labour applied humour to assert and demand action from the management. In lines 1 through 5, M1 asked labour to reconsider management's wage increase proposal. Labour answered by joking about there being nothing new in management's proposition (lines 7 through 10). Then, good-humouredly, L1 said in the next turn that it looked like management did not want the bargaining process to end yet, to which M1 responded (line 12) with an assurance that management, like labour, also wanted both parties to come to an agreement soon. In a lighthearted manner, labour pressured management to increase its offer and hasten the negotiation process. An example of how labour displayed doubt about management's sincerity is found in Extract 2C, where aside from laughing at M1's every line, labour also goaded him at every turn with words like ‘ikaw lang naman ang lumalayo’ (you are the one who is moving farther) in lines 4 and 5, and ‘bola’ (you’re fibbing) in line 7. Labour even mocked management by suggesting an exorbitant amount and following it with laughter. M1's answer of ‘hindi naman’ (that can't be) was drowned in L's laughter.

Extract 2C:

Labour also used humour to pressure and threaten management. The following excerpts are examples of this.

Extract 2D:

In lines 1 through 7, M1 tried to coax labour negotiators to cooperate to hasten the bargaining process. L1 replied that labour was not yet ready. Then L, picking up on what M1 said in lines 4 to 5 (demonstrate), said in line 13 that they will indeed protest (demonstration is a word used to describe protest), to which L2 laughed (line 14). L's declaration of possible demonstration is clearly a show of warning to management.

Extract 6A:

Similarly, with L3 saying that labour would have another representative in the next negotiation (lines 3 to 4 in Extract 6A) supported by L2's ‘pagka hindi ko hindi ako nasiyahan sa bigay ni::: M1 mamumundok ako’ (if I won't be happy with what M2 will offer, I will go to the mountains) and simultaneous laughter from the other interactants, labour was openly threatening management to make certain that labour should be pleased and satisfied with the end result of the negotiation. Going to the mountains in this context implies joining the anti-government armed struggle in mountainous rural areas in the Philippines.

Extract 6E:

In the above excerpt, L2 requested M1 for a break (line 1) to which M1 readily concurred (line 2). In the next turn, however, L2 added that the reason for the break was so labour could discuss the latest death threat of management. The statement was followed by a short laugh at the end to indicate that he was actually just joking. M1's reply of ‘di naman death threat’ (it is not death threat) followed by a particle of laughter confirmed that he understood the joke and that he did not take offence to L2's statement. Labour can be seen here drawing on humour to express criticism of management's proposal.

Labour also tried to draw on humour to do power by de-emphasising the power gap between labour and management. Instances in the data where humour was used by labour in doing power were observed during discussions on the amount of employee wage increase, as can be seen in Extract 1F.

Extract 1F:

In the above example, lines 1 through 6 show labour as trying to convince management to increase the proposed salary hike to more than 6%. In the next turn, M2 protested that it was too high, which L2 jokingly countered in line 8 with a question, ‘ang taas ba?’ (is it?). Here, L2's question was aimed at legitimising labour's proposition. Ending his sentence with a full laugh (huh) indicated that L2 meant the question to be humourous, so as to soften the impact of his message. In this instance, use of humour helped achieved the goal of establishing the validity of labour's proposition.

Below is an example of an instance when labour tried to delegitimise management's offer as well as to express its opinion. Humour, however, helped temper the impact of labour's statement.

Extract 3A:

In lines 1 through 6, M1 was trying to go over labour's proposal when in line 8, L3 cheerily cut M1 off by saying he was actually just mimicking what labour was saying, producing laughter from the other negotiators. Such usage of humour allowed labour to bravely articulate its thoughts and face up to authority. In the next turn (line 10), L2 took advantage of the lighthearted mood by good-humouredly asking management if it could increase the pay hike some more. Such an act allowed labour to insist on a bigger offer and persuade management to provide a better deal.

Similar efforts by labour to de-emphasise the power gap can be seen in the continuation of Extract 6B below.

Continuation of Extract 6B:

In an attempt to end the discussion on employees’ wage increase, M1 in line 30 declared they had already reached maximum limit with his ‘kahit saan pa kayo umakyat’ (no matter where you go). L's answer in line 33 showed how labour tried to shift the power symmetry, drawing on a joking tone. With L3's support (line 35) of ‘oo’ (yes) to L's move, M1 in the next turn (lines 36 to 37) acceded by trying to explain his prior statement. Humour thus served as an instrument for labour to scale down the power disparity between them.

Negotiators Sharing a Laugh to Promote Harmony

Management and labour also brought humour into play to enhance esprit de corps and promote harmony among the negotiators. Both parties engaged in bantering and playful teasing, creating a blithe atmosphere during the negotiation process. They also tended to play along with a joke and/or counter it with another. The humour shared by management and labour brought to light the things that they share in common, making them identify with each other, while at the same time reducing the antagonism brought about by the bargaining process.

In the following extract, we can see both parties bantering with each other, bringing to light the verity that they share something in common.

Extract 6L:

Lines 3 through 6 showed both management and labour making light teasing remarks about their deal being off the record. The short laugh at the end of L1 and L2's utterances in lines 3 and 4 hinted this. M1's joining in, in line 6, suggested that both parties were amenable to it. In the next turn (line 7), M2 jestingly asked for L3 to do the presentation, which L1 instantaneously agreed to, as can be seen in line 8. The laughter that followed in line 9 denotes that the interactants shared a private joke about L3's capability to present. Both parties likewise exchanged jokes (see Extract 6H). The humour behind the joke did not just hint at some form of connection, but conveyed that both parties agreed with each other as well.

Extract 6H:

Lines 1 through 11 show M and L3 bantering about L3's skill as a negotiator, with the other interlocutors laughing with them in the background (lines 4 and 11). M2 joined in the exchange in lines 12–18, praising L3's knack on the bargaining table. Even though M2 was commending L3, he was also good humouredly saying that L3's ability can actually be to management's advantage. Seeing the joke behind the comment, the rest of the negotiators responded with simultaneous laughter (lines 13, 15 and 18). Laughing together at L3's negotiating ability showed that both parties shared the joke.

The next two excerpts are instances where labour and management were actually haggling, expressing a critical bargaining position, yet the humour behind their jokes denoted a move towards solidarity from both parties.

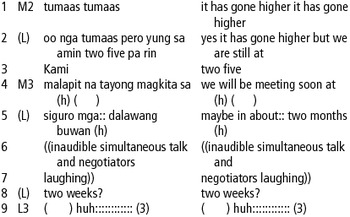

Extract 7F:

In lines 2 and 3, labour seemed to be expressing discontent with the turn of the bargaining process. M3's response was to reassure him that they were almost reaching an agreement with ‘malapit na tayong magkita’ (we will be meeting soon), in a deprecating manner, as shown by his short laugh at the end of his sentence. Labour's response was to jokingly suggest possible target dates (lines 5 and 8). Although there was a bit of seriousness there indicating that labour was not happy with the delays, the short laugh at the end of line 5 and the laughter from other interactants hinted at humour, willingness to cooperate from the labour's side, as well as understanding from the rest of the negotiators.

Extract 8D:

Lines 1 through 3 above showed management's way of communicating its bargaining position, stating it negatively to employ humour. The message was an action showing acceptance of labour's proposition. The simultaneous loud laughter, cheering and clapping in the next turn revealed that everyone was pleased with the end result of the negotiation.

Discussion

Findings show consistencies in the functions of humour in wage bargaining and in other power-differentiated interactions discussed in the review of literature. Humourous conversations were consciously or subconsciously used by labour and management to maintain solidarity. Humour was likewise employed by labour to subvert authority through exerting pressure on and expressing doubt and criticism of management, and by the management negotiators to control the dynamics of the negotiation by breaking free of an impasse and subduing labour. Through conversation analysis, the study was able to determine how humour was utilised by both parties to challenge or maintain power relations in a manner that does not undermine their shared goal of achieving a wage bargaining agreement.

Humour as Management's Means to Maintain Power

Because management exercises control over company resources, power in wage bargaining conversations is usually tipped to their side (Alavoine, Reference Alavoine2012). Research on humour in power-differentiated interactions suggests that in conversations between asymmetric groups, it is those who wield power who use humour to exert control over conversations. This is done to suppress the undesired behaviour of the less dominant (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Banas, Rodriguez, Liu and Abra2012) and manage interactions to break free of an impasse (Maemura & Horita, Reference Maemura and Horita2012). As a way of managing conversations, humour seems to enable management to put forth their competitive goals to gain more from the negotiation (Adair & Loewenstein, Reference Adair, Loewenstein, Olekalns and Adair2013) while pursuing the shared goal of arriving at an agreement.

Achieving competitive goals can be seen in conversations that show management as doing power and subduing labour. Management's direct criticism of labour's claim for a ‘high’ wage increase (e.g. Extract 6B) is an example of doing power. In this instance, management used joking as a way of standing firm on their bargaining position and attacking labour's position. The use of humour shifted and/or maintained the light atmosphere on the bargaining table as the conversation sequence concluded with simultaneous laughter.

On the other hand, efforts to suppress labour's undesired behaviours of engaging in protest action can be seen in Extract 2S, wherein labour's explicit warning to hold a picket was jokingly dealt with by a management negotiator. This was done by emphasising a mispronounced word (pikit instead of piket), which was similarly followed by simultaneous laughing of the bargaining parties.

As the high-power group, management negotiators are expected to behave competitively to enhance their gains (Olekalns & Adair, Reference Olekalns, Adair, Olekalns and Adair2013). Of all the possibilitites in the conversation extracts presented above, management could have used a more offensive and confrontational approach in criticising labour's claims for a bigger wage increase and threat of protest action. By using humour, management was still able to put forth its competitive goals while keeping the negotiation going. It is also through humour that management negotiators were able to break free of gridlocks (e.g., Extract 6C), which if not handled properly may at the extreme lead to a breakdown in negotiation (Edralin, Reference Edralin2003; del Rosario, Reference Del Rosario, Diamante and Ledesma-Tan2007).

Labour Expressing Its Voice and Challenging Hegemony Through Humour

Using humourous talk allowed labour to put forth its bargaining position and tilt power to their side, without putting the negotiation at the verge of a deadlock. As seen in literature, humour allows the less dominant group to challenge hegemony, resist authority and do power in a non-threatening way (Holmes, Reference Holmes2000; Holmes & Marra, Reference Holmes and Marra2002; Martin, Reference Martin2006).

Doing power through humour can be seen in labour's justification of their claim for a bigger wage increase (Extract 1F) and in their efforts to persuade management to present a better offer (Extracts 3A), through teasing and joking. Similarly, labour used humour to lightheartedly challenge management's claim of reaching their bargaining limit in Extract 6B. Doing so showed a successful move by labour to shift the power asymmetry. The preceding humourous talk shaped the succeeding utterance of the main management negotiator (M1), forcing him to take a softer stance in lines 36 and 37.

Humour also served as a useful way of expressing labour's voice to challenge management authority. This was seen in how labour articulated potentially offensive opinions of management, such as management's seeming disinterest to hasten the negotiation process (Extract 6K), the unacceptable wage offer (Extract 6E), and their doubts about management's sincerity (Extract 2C). Labour likewise conveyed through humour their readiness to engage in protest actions (Extracts 2D and 6A).

As seen in other power-differentiated interactions where humour was utilised by the less dominant group to effectively communicate criticism and dissatisfaction, contest the status of the more influential, and express defiance in a non-threatening way (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Banas, Rodriguez, Liu and Abra2012; Holmes & Marra, Reference Holmes and Marra2002; Martin, Reference Martin2006), labour was able to artfully use humour to put forth its bargaining position and defy management authority. In using humour rather than direct confrontation, labour was able to express bargaining positions and challenge management authority in a way that demonstrated its desire to keep the negotiation going. Similar to management, this reflects how labour put forth its competitive goals in a manner that conveyed its desire to eventually reach a wage bargaining agreement.

The issue of wage increase is described in literature as one of the most contested topics in labour-management negotiations (Edralin, Reference Edralin2003). Using more explicit means of doing power, controlling the bargaining conversations and subverting authority such as through impositions and offensive talk may push the bargaining parties to a more direct show of force. In the case of labour, this can be by engaging in protest actions to even out the positioning of both parties at the negotiation table. In the Philippines and in other Southeast/East Asian cultures, conversations that emphasise the less dominant position of labour or that explicitly challenge management authority may be perceived as going against the norms of saving face and maintaining harmony (Aslani et al, Reference Aslani, Ramirez-Marin, Semnani-Azad, Brett, Tinsley, Olekalns and Adair2013). While labour may perceive this as a blatant display of power, management may see it as disrespectful, and both may view it as lacking in value for a long-term relationship. In using humour, management and labour were still able to put forth their competitive goals through talk that preserved or defied asymmetry in power, while indirectly shaping the succeeding positive responses of the other party. This is because interactional norms dictate that humour in conversations is responded to in a humourous or agreeable way rather than in an antagonistic manner (Barnes, Palmary, & Durheim, Reference Barnes, Palmary and Durrheim2001).

The Importance of Maintaining Harmonious Intergroup Relationship

Utilising humour to pursue competitive goals and at the same time work towards signing a wage bargaining agreement may not have been possible if the negotiating parties did not have a historically agreeable relationship. This harmonious relationship is reflected in instances where labour and management negotiators engaged in humourous talk that brought to light what they share in common and how much they identify with each other. Instances where both parties shared private jokes, bantered and teased each other or one of the negotiators (Extracts 6L, 6H and 7F) highlighted commonality and harmony. As pointed out in the literature, humour shared by interacting parties conveys the message that they share something in common and engenders a ‘we-feeling’ among the negotiators (Lipovsky, Reference Lipovsky2012; Martin, Reference Martin2006). These feelings of affiliation (Lipovsky, Reference Lipovsky2012) reduce tension in potentially heated discussions (Martin, Reference Martin2006; Meyer, Reference Meyer2000) such as in wage bargaining.

The findings of the study point to the utility of humour in managing wage bargaining conversations that put forth the competitive goals of negotiating parties, while aiming to achieve a shared agreement. Humour in power-differentiated bargaining seems particularly useful in cultures that value face-saving and preserving harmony. Through humourous talk, efforts to maintain and challenge the power dynamics are achieved but are camouflaged in lighthearted conversations that make agreement constantly possible. Humour in a conversation sequence leads the other interlocutors to positively respond to utterances that if stated in another way might elicit antagonistic responses.

Implications for Practice

The findings are particularly useful for multinational corporations that operate or seek to operate in Southeast Asian countries with historically tumultuous labour relations, such as the Philippines. These results may be used to select management negotiators and to orient them on the utility of humour in effectively navigating through wage bargaining conversations. Findings also point to the importance of maintaining harmony inside and outside wage bargaining. Conversations characterised with humour seem possible if positive relationships are constantly nurtured. This implies that management must promote programs that will encourage constant dialogue and intergroup teambuilding that creates a ‘we-feeling’ among the management and labour negotiators.

The findings can also be useful for choosing and training labour negotiators in similar contexts. Insights from the study may guide labour in devising strategies to express their voice as the underdog in the negotiation and to challenge asymmetries in power without prejudicing the goal of achieving wage bargaining agreements.

Limitations and Implications for Research

The study examined the role of humour in power-differentiated wage bargaining conversations that successfully achieved a wage bargaining agreement. Due to the difficulty of acquiring audio-recorded data and the permission to use these from both labour and management groups, we utilised data from one organisation only. Although the current findings demonstrate the utility of humour in this kind of interaction, it may be interesting to compare the occurrence of humour in successful and unsuccessful wage negotiations longitudinally in one organisation or across organisations.

Also, because culture was found to influence the bargaining conversations through humourous talk, future research may take a cross-cultural perspective and explore if and how humour is utilised in bargaining among negotiators of varying national cultures.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted through a grant from the Ateneo de Manila University Loyola Schools Scholarly Work Faculty Grants.

Appendix

Selected Transcription Keys for Data Extracts

(adapted from Woofitt, Reference Wooffitt2005, and Wilkinson and Kitzinger, Reference Wilkinson, Kitzinger, Harré and Moghaddam2003)