It is our sad duty to report to the Paleontological Society on the loss of a dear friend and valued colleague. James Clinton Brower, paleontologist and Professor Emeritus of Earth Sciences at Syracuse University, passed away at his home on April 9th at the age of 83, with his wife and true soulmate, Karen, at his side. Jim was a towering figure in echinoderm paleobiology and in the numerical/statistical treatment of paleobiological data. He taught at SU for 33 years and remained an active member of the faculty following his retirement, regularly publishing papers, participating in seminars, and serving on thesis committees.

Jim earned his Bachelors and Masters degrees from American University following his service in the Korean War. He then moved to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he completed his PhD dissertation entitled “Evolution and classification of primitive actinocrinitids” (Brower, Reference Brower1964) under the mentorship of Lowell Laudon. After graduation, he moved with his first wife, June, to Syracuse where he enjoyed a long and successful career. He and June had two sons, Jeffrey and Richard, prior to June’s death in 1982. In 1989, he married Karen and they were together for 29 wonderful years until his passing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Jim and Karen Brower in 2010. Photo by Richard Ivany.

Jim is especially well known for his careful and detailed work on the taxonomy, functional morphology, ontogeny, and paleoecology of Paleozoic crinoids, and for his rigorous numerical treatment of data. For crinoid workers, Jim was, paradoxically, a link to the past and at the same time an innovator who helped point the way forward for paleobiological study of fossil crinoids and other groups. Jim’s dissertation advisor together with Raymond C. Moore developed our basic understanding of crinoids, as summarized in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (Moore and Teichert, Reference Moore and Teichert1978), so he was well-grounded in that classical work. At the same time, Jim provided the initial and essential push for the next generation of crinoid study, using modern numerical techniques and an appreciation of function and physiology to better constrain our understanding of the group moving forward. Whether it was ontogeny, phylogenetics, or niche modeling, and always with a welcoming smile, Jim was our example of best practices for interpretation of the crinoid fossil record.

Jim’s early work was on Mississippian crinoids, but much of his career was devoted to Ordovician crinoids. Crinoids became the dominant group of echinoderms during the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), and Jim’s careful study of these crinoids is an essential part of our current understanding of the taxonomy, phylogeny, diversification, and paleoecology of this dominant group of Paleozoic organisms. Among his many papers are comprehensive surveys of the echinoderm faunas of classic Ordovician assemblages, including most recently the Walcott-Rust Quarry in New York (Brower, Reference Brower2005, Reference Brower2008, Reference Brower2010, Reference Brower2011) and the Dunleith Formation in Iowa and Minnesota (Brower, Reference Brower2013). He was working with colleagues in Montreal to describe a spectacular assemblage from the Neuville Formation in Quebec when he passed (e.g., Brower et al., Reference Brower, Iellamo and Cournoyer2014), and one of us (WIA) will be taking up the mantle of that work to ensure it gets completed in his name. A beautiful example of this material is shown in the accompanying photo from Jim’s work (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 At least ten complete juvenile specimens of Ectenocrinus simplex (Hall, Reference Hall1847) attached to a hardground within the Upper Ordovician Neuville Formation near Quebéc City in Canada. Jim found that lengthening of the stem follows a logistic pattern, with relatively slow growth in the youngest crinoids, a “middle aged” growth spurt during which stem length increases extremely rapidly, then comparatively slow growth in the adult phase. This growth sequence offers a general model that can be extrapolated to other stalked crinoids in which complete specimens are known but growth sequences are not available. Reconstruction of stem lengths allows for study of how progressively larger and older individuals can position their calices further above the seafloor. This suggests partitioning of space and food resources, a finding augmented also by Jim’s work on food-groove widths and tube-foot spacing (e.g., Brower, Reference Brower2011) (photo by Jim Brower; text paraphrased from Jim’s contribution to the Dept. of Earth Sciences Alumni Newsletter from 2017).

Among his many notable contributions were his studies on ontogenetic allometry in Paleozoic crinoids. Already in his early work on the topic (as seen in Moore and Teichert, Reference Moore and Teichert1978), he focused on how morphology of crinoid feeding structures scaled with body size through ontogeny, hypothesizing that the relationship should be governed by an energy balance between nutrients captured and metabolic requirements. The general theme of ontogenetic scaling of crinoid feeding was to remain a focus throughout his career, and his approach continued to evolve, ultimately resulting in models that combined morphological and environmental parameters within the paradigm of filtration theory (Brower, Reference Brower2007). Characteristic of all these studies is the rich, exceptionally detailed morphometric data, the statistical rigor of analysis, and their grounding in sound biological and biomechanical principles (e.g., Brower, Reference Brower1987).

Jim’s studies of functional morphology through the application of biomechanics was not restricted to crinoids. Through quantitative modeling he provided compelling evidence for the respiratory function of pectinirhombs in pleurocystitids (Brower, Reference Brower1999), and he was one of the first to rigorously explore the aerodynamics of Mesozoic flying reptiles (Brower and Veinus, Reference Brower and Veinus1981; Brower, Reference Brower1983).

A strong advocate for the use of statistical and mathematical methods in the field of paleobiology, Jim also orchestrated a number of studies on the quantitative paleoecology of the local Middle Devonian Hamilton Group fauna (e.g., Brower et al., Reference Brower, Nye, Belak, Carey, Leetaru, Macadam, Millendorf, Salisbury, Thompson, Willette and Yamatoto1978; Brower and Nye, Reference Brower and Nye1991; Bonuso et al., Reference Bonuso, Newton, Brower and Ivany2002), assessing patterns of faunal association and change with a battery of numerical techniques. His statistical expertise and logical approach to problem solving is perhaps one of his greatest gifts to the many students that came through the program at Syracuse, be they his own graduate students or one of the many who benefited from his tutelage in classes, seminars, and committee meetings. At SU’s Commencement ceremony and departmental reception this year, faculty members honored Jim by wearing lapel pins featuring crinoids. (Yes, they are indeed available, and quite beautiful, although Jim would have cringed at the depiction of arm position!).

On one thing people who knew Jim will agree—he loved what he did. Even in ‘retirement,’ when he was in town he could usually be found in his office at SU. A walk past his open door would typically offer a glimpse of the high-resolution digital photos of crinoids he was working on, open on his computer screen while he attentively worked on figures. He would often stroll into my (LCI’s) office unannounced, his ever-present headband magnifier lenses perched on his head, and with a big grin plop into my extra chair and begin a conversation about whatever he was thinking about at the time. Some days it was food-groove widths, some days scaling of metabolic rate with body size, and sometimes it was the application of multivariate statistics to anything ranging from faunal turnover to water chemistry. And once he got talking it was hard to deter him, so clear was his enthusiasm for the science. One of my (LCI’s) most favorite memories is getting an email from TKB late one afternoon, pleading with me to go by Jim’s office and distract him so that Tom could gracefully extract himself from what had become a rather long phone conversation about food grooves and filtration theory. He had another meeting he needed to go to but didn’t have the heart to end the conversation himself! Jim loved what he did, he could talk about it for hours, and you couldn’t help but love him for it.

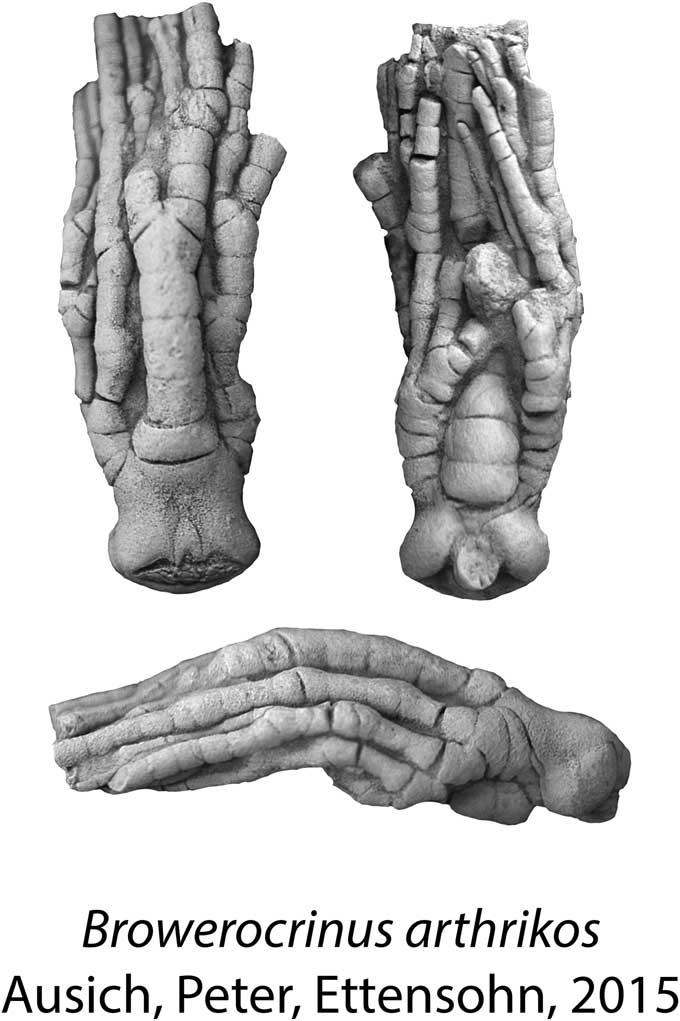

Jim’s substantial influence on the field is memorialized in the erection of a new genus, Browerocrinus Ausich, Peter, and Ettensohn, Reference Ausich, Peter and Ettensohn2015 (Fig. 3)—a lasting recognition of his contributions to paleontology and his long fascination with the Calceocrinidae.

Figure 3 Three views of the holotype specimen (USNM 594961—US National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC) of the calceocrinid Browerocrinus arthrikos Ausich, Peter, and Ettensohn, Reference Ausich, Peter and Ettensohn2015 from the Silurian of Kentucky, named in Jim’s honor.

James C. Brower was an outstanding scholar of the Crinoidea and a wonderful colleague. We will miss his easy smile, his faux-cantankerous but unfailingly upbeat nature, his passion for his science, and the open willingness to help that he always showed to students and colleagues alike. Paleontology has lost a good one, but his influence on the field will live on for generations to come.

In Jim’s memory, his family has asked people to consider donations to the Department of Earth Sciences at Syracuse University, 204 Heroy Geology Laboratory, Syracuse, NY 13244.