1. Introduction

The geometry of a stellarator's magnetic field needs to be designed to achieve good confinement, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) stability and other desirable properties. In recent stellarator experiments such as HSX and W7-X, this design was performed by optimizing an objective function computed from numerical MHD equilibrium solutions. This approach suffers from the fact that the optimization algorithm can get trapped in local minima of the objective function, and relatively little insight is gained into the space of solutions. To address these issues, we have recently developed a complementary approach based on a high-aspect-ratio approximation (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018; Landreman Reference Landreman2019; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Landreman, Sengupta & Plunk Reference Landreman, Sengupta and Plunk2019; Plunk, Landreman & Helander Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019; Jorge, Sengupta & Landreman Reference Jorge, Sengupta and Landreman2020a,Reference Jorge, Sengupta and Landremanb). In this complementary approach, the three-dimensional shape of magnetic surfaces are directly constructed to achieve a desired magnetic field strength in Boozer coordinates. This ‘near-axis construction’ method is based on an expansion devised by Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991a,Reference Garren and Boozerb). The reduced equations can be solved many orders of magnitude faster than the three-dimensional MHD equilibrium solution required at each iteration of traditional stellarator optimization.

Past work on the near-axis construction has focused on neoclassical confinement, through the properties of quasisymmetry and omnigenity (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Landreman et al. Reference Landreman, Sengupta and Plunk2019; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019). Recently it has been shown that within this approach, magnetic well and Mercier stability can be computed (Landreman & Jorge Reference Landreman and Jorge2020). One can also evaluate the geometric quantities entering the gyrokinetic equation for microinstabilities and turbulence (Jorge & Landreman Reference Jorge and Landreman2021). In the present paper, we show how a number of other useful quantities can be computed directly from a solution of the near-axis equations. In future work, these figures of merit could be targeted during optimization within the space of near-axis solutions. Such an optimization would have the advantage that the objective function could be evaluated orders of magnitude faster than in traditional stellarator optimization based on full three-dimensional equilibrium calculations. The figures of merit derived here could also be applied to high-resolution scans over parameter space, which are made possible by the speed of the near-axis approach. Specifically, during such a scan over near-axis configuration parameters, the figures of merit here could be used to identify regions of parameter space that are uninteresting due to the need for close electromagnetic coils, unreasonably high aspect ratio, or large errors in quasisymmetry. Attention could then be focused on the remaining regions of parameter space.

The first quantities we will evaluate, in § 3, are the tensors ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ along the magnetic axis, where

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ along the magnetic axis, where ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ is the magnetic field. These tensors are useful for two reasons. First, electromagnetic coils can be designed to produce a field matching these tensors, which (for vacuum fields) means they produce the desired stellarator configuration (Giuliani et al. Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020). Second, these tensors encode all the scale lengths in the magnetic field (up to the order of interest), reflecting how far away the coils may be from the axis. Configurations with short scale lengths in

$\boldsymbol {B}$ is the magnetic field. These tensors are useful for two reasons. First, electromagnetic coils can be designed to produce a field matching these tensors, which (for vacuum fields) means they produce the desired stellarator configuration (Giuliani et al. Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020). Second, these tensors encode all the scale lengths in the magnetic field (up to the order of interest), reflecting how far away the coils may be from the axis. Configurations with short scale lengths in ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ are likely to require very close coils, which is undesirable. Next, in § 4, we compute the maximum minor radius for which the constructed surface shapes are smooth and nested. This critical minor radius is equivalent to a minimum aspect ratio, beyond which the near-axis construction does not give physical surface shapes. Configurations for which this minimum aspect ratio is large can then be rejected. We also show in § 4.4 that this limit on the aspect ratio is related to an equilibrium limit on

$\boldsymbol {B}$ are likely to require very close coils, which is undesirable. Next, in § 4, we compute the maximum minor radius for which the constructed surface shapes are smooth and nested. This critical minor radius is equivalent to a minimum aspect ratio, beyond which the near-axis construction does not give physical surface shapes. Configurations for which this minimum aspect ratio is large can then be rejected. We also show in § 4.4 that this limit on the aspect ratio is related to an equilibrium limit on ![]() $\beta$, the ratio of plasma to magnetic pressure. Finally, in § 5, we consider the case in which the surface shapes are constructed to give some desired pattern of

$\beta$, the ratio of plasma to magnetic pressure. Finally, in § 5, we consider the case in which the surface shapes are constructed to give some desired pattern of ![]() $B$ in Boozer coordinates to first order (in inverse aspect ratio). The ‘error field’ associated with the

$B$ in Boozer coordinates to first order (in inverse aspect ratio). The ‘error field’ associated with the ![]() $B$ at next order is computed. This information could enable the parameters of the near-axis equations to be optimized so that this error field is small.

$B$ at next order is computed. This information could enable the parameters of the near-axis equations to be optimized so that this error field is small.

All numerical calculations shown in this paper were carried out using the code in Landreman (Reference Landreman2020a), with data available in Landreman (Reference Landreman2020b).

2. Notation

We employ the ‘inverse expansion’ of Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991a,Reference Garren and Boozerb), while using identical notation to Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019), hereafter denoted LS. Several key definitions are repeated here for convenience. In Boozer coordinates, the magnetic field has the forms

where ![]() $\theta$ and

$\theta$ and ![]() $\varphi$ are the poloidal and toroidal Boozer angles,

$\varphi$ are the poloidal and toroidal Boozer angles, ![]() $2{\rm \pi} \psi$ is the toroidal flux,

$2{\rm \pi} \psi$ is the toroidal flux, ![]() $I$ and

$I$ and ![]() $G$ are constant on

$G$ are constant on ![]() $\psi$ surfaces and

$\psi$ surfaces and ![]() $\iota (\psi )$ is the rotational transform. To facilitate calculations with quasihelical symmetry, it is convenient to introduce a helical angle

$\iota (\psi )$ is the rotational transform. To facilitate calculations with quasihelical symmetry, it is convenient to introduce a helical angle ![]() $\vartheta = \theta - N \varphi$, where

$\vartheta = \theta - N \varphi$, where ![]() $N$ is a constant integer that can be set to zero if not considering quasihelical symmetry. Then

$N$ is a constant integer that can be set to zero if not considering quasihelical symmetry. Then

where ![]() $\iota _N = \iota - N$.

$\iota _N = \iota - N$.

The position vector ![]() $\boldsymbol {r}$ at an arbitrary point can be written as

$\boldsymbol {r}$ at an arbitrary point can be written as

where ![]() $\boldsymbol {r}_0(\varphi )$ is the position vector along the magnetic axis. The Frenet–Serret unit vectors of the axis

$\boldsymbol {r}_0(\varphi )$ is the position vector along the magnetic axis. The Frenet–Serret unit vectors of the axis ![]() $(\boldsymbol {t},\boldsymbol {n},\boldsymbol {b})$ satisfy

$(\boldsymbol {t},\boldsymbol {n},\boldsymbol {b})$ satisfy

and ![]() $\boldsymbol {t}\times \boldsymbol {n}=\boldsymbol {b}$. Here,

$\boldsymbol {t}\times \boldsymbol {n}=\boldsymbol {b}$. Here, ![]() $\kappa (\varphi )$ is the axis curvature,

$\kappa (\varphi )$ is the axis curvature, ![]() $\tau (\varphi )$ is the axis torsion and

$\tau (\varphi )$ is the axis torsion and ![]() $\ell$ is the arclength along the axis.

$\ell$ is the arclength along the axis.

The expansion about the magnetic axis is developed by writing

where the effective minor radius coordinate ![]() $r$ is defined via

$r$ is defined via ![]() $2 {\rm \pi} \psi = {\rm \pi} r^2 \bar {B}$, and where the constant

$2 {\rm \pi} \psi = {\rm \pi} r^2 \bar {B}$, and where the constant ![]() $\bar {B}$ is a reference field strength. The quantities

$\bar {B}$ is a reference field strength. The quantities ![]() $Y$ and

$Y$ and ![]() $Z$ in (2.4) are expanded analogously. All scale lengths in the system except

$Z$ in (2.4) are expanded analogously. All scale lengths in the system except ![]() $r$ are ordered as comparable to a large length scale

$r$ are ordered as comparable to a large length scale ![]() $\mathcal {R}$, from which we define the expansion parameter

$\mathcal {R}$, from which we define the expansion parameter ![]() $\epsilon = r / \mathcal {R}$. Then (2.6) represents an expansion in

$\epsilon = r / \mathcal {R}$. Then (2.6) represents an expansion in ![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$. We expand

$\epsilon \ll 1$. We expand ![]() $B$ and

$B$ and ![]() $\beta$ in a similar way to (2.6) but with an

$\beta$ in a similar way to (2.6) but with an ![]() $O(\epsilon ^0)$ term as follows:

$O(\epsilon ^0)$ term as follows:

The radial profiles ![]() $G(r)$,

$G(r)$, ![]() $I(r)$,

$I(r)$, ![]() $p(r)$ and

$p(r)$ and ![]() $\iota _N(r)$ have expansions with only even powers of

$\iota _N(r)$ have expansions with only even powers of ![]() $r$, since they must be even in

$r$, since they must be even in ![]() $r$:

$r$:

In the analogous expansion of ![]() $I(r)$,

$I(r)$, ![]() $I_0 = 0$ since

$I_0 = 0$ since ![]() $I(r)$ is proportional to the toroidal current inside the surface

$I(r)$ is proportional to the toroidal current inside the surface ![]() $r$. Considering that physical quantities should be analytic at the magnetic axis, the expansion coefficients have the form

$r$. Considering that physical quantities should be analytic at the magnetic axis, the expansion coefficients have the form

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} X_1(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{1s}(\varphi) \sin(\vartheta) + X_{1c}(\varphi) \cos(\vartheta), \\ X_2(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{20}(\varphi) + X_{2s}(\varphi) \sin(2\vartheta) + X_{2c}(\varphi) \cos(2\vartheta), \\ X_3(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{3s3}(\varphi) \sin(3\vartheta) + X_{3s1}(\varphi) \sin(\vartheta)\\ & \quad + X_{3c3}(\varphi) \cos(3\vartheta) + X_{3c1}(\varphi) \cos(\vartheta). \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} X_1(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{1s}(\varphi) \sin(\vartheta) + X_{1c}(\varphi) \cos(\vartheta), \\ X_2(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{20}(\varphi) + X_{2s}(\varphi) \sin(2\vartheta) + X_{2c}(\varphi) \cos(2\vartheta), \\ X_3(\vartheta,\varphi) & = X_{3s3}(\varphi) \sin(3\vartheta) + X_{3s1}(\varphi) \sin(\vartheta)\\ & \quad + X_{3c3}(\varphi) \cos(3\vartheta) + X_{3c1}(\varphi) \cos(\vartheta). \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

(A detailed discussion is given in appendix A of Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018).) The quantities ![]() $Y$,

$Y$, ![]() $Z$,

$Z$, ![]() $B$ and

$B$ and ![]() $\beta$ have expansion coefficients of the same form as (2.9).

$\beta$ have expansion coefficients of the same form as (2.9).

Next, we apply the dual relations, ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla } r=(\partial \boldsymbol {r}/\partial \vartheta \times \partial \boldsymbol {r}/\partial \varphi )/\sqrt {g}$ and cyclic permutations, where

$\boldsymbol {\nabla } r=(\partial \boldsymbol {r}/\partial \vartheta \times \partial \boldsymbol {r}/\partial \varphi )/\sqrt {g}$ and cyclic permutations, where ![]() $\sqrt {g}=(\boldsymbol {\nabla } r\boldsymbol {\cdot \nabla }\vartheta \times \boldsymbol {\nabla }\varphi )^{-1}=(G+\iota I)r\bar {B}/B^2$ is the Jacobian of the

$\sqrt {g}=(\boldsymbol {\nabla } r\boldsymbol {\cdot \nabla }\vartheta \times \boldsymbol {\nabla }\varphi )^{-1}=(G+\iota I)r\bar {B}/B^2$ is the Jacobian of the ![]() $(r,\vartheta ,\varphi )$ coordinates. Derivatives of the position vector (2.4) are substituted into the dual relations to obtain the vectors

$(r,\vartheta ,\varphi )$ coordinates. Derivatives of the position vector (2.4) are substituted into the dual relations to obtain the vectors ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla } r$,

$\boldsymbol {\nabla } r$, ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\vartheta$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\vartheta$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\varphi$. These gradient vectors are then substituted into (2.2)

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\varphi$. These gradient vectors are then substituted into (2.2) ![]() $=$ (2.3) and

$=$ (2.3) and ![]() $(\boldsymbol {\nabla }\times \boldsymbol {B})\times \boldsymbol {B} = \mu _0 \boldsymbol {\nabla } p$. The condition

$(\boldsymbol {\nabla }\times \boldsymbol {B})\times \boldsymbol {B} = \mu _0 \boldsymbol {\nabla } p$. The condition ![]() $B(r,\vartheta ,\varphi )=B(r,\vartheta )$ can also be imposed if one desires quasisymmetry. Equations are thereby obtained at each order in

$B(r,\vartheta ,\varphi )=B(r,\vartheta )$ can also be imposed if one desires quasisymmetry. Equations are thereby obtained at each order in ![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$. These equations can be found in the appendix of Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991a) and appendix A of LS.

$\epsilon \ll 1$. These equations can be found in the appendix of Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991a) and appendix A of LS.

We note two signs that appear in the analysis: ![]() $s_G = \mathrm {sgn}(G) = \pm 1$ and

$s_G = \mathrm {sgn}(G) = \pm 1$ and ![]() $s_\psi = \mathrm {sgn}(\psi ) = \mathrm {sgn}(\bar {B}) = \pm 1$. As discussed in appendix A.1 of Landreman & Jorge (Reference Landreman and Jorge2020), these signs are associated with the choice of

$s_\psi = \mathrm {sgn}(\psi ) = \mathrm {sgn}(\bar {B}) = \pm 1$. As discussed in appendix A.1 of Landreman & Jorge (Reference Landreman and Jorge2020), these signs are associated with the choice of ![]() $\varphi$ and

$\varphi$ and ![]() $\theta$: each sign can be flipped by reversing the direction in which these angles increase. If one is considering quasisymmetry, the normalizing field can be taken to be

$\theta$: each sign can be flipped by reversing the direction in which these angles increase. If one is considering quasisymmetry, the normalizing field can be taken to be ![]() $\bar {B} = s_\psi B_0$.

$\bar {B} = s_\psi B_0$.

With the notation and expansion now defined, we proceed to derive the new figures of merit that can be computed from these expansion coefficients.

3. The  $\nabla B$ and

$\nabla B$ and  $\nabla \nabla B$ tensors

$\nabla \nabla B$ tensors

There are several reasons why it is valuable to evaluate the tensors ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ on the magnetic axis in terms of the near-axis expansion coefficients. First, consistency between these tensors and the magnetic field from the Biot–Savart formula can be achieved by numerical optimization, enabling direct optimization of coil shapes for quasisymmetry. Demonstrations of this method for

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ on the magnetic axis in terms of the near-axis expansion coefficients. First, consistency between these tensors and the magnetic field from the Biot–Savart formula can be achieved by numerical optimization, enabling direct optimization of coil shapes for quasisymmetry. Demonstrations of this method for ![]() $O(\epsilon )$ quasisymmetry are presented in Giuliani et al. (Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020), in which the formula for

$O(\epsilon )$ quasisymmetry are presented in Giuliani et al. (Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020), in which the formula for ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ derived here is used. It may be possible to optimize coils for

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ derived here is used. It may be possible to optimize coils for ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ quasisymmetry (requiring

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ quasisymmetry (requiring ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$) in future work.

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$) in future work.

Second, ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ provide information about how feasible it is to generate a given near-axis stellarator solution using distant magnets. This is because

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ provide information about how feasible it is to generate a given near-axis stellarator solution using distant magnets. This is because ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ encodes all the (inverse) scale lengths in the magnetic field that can be known from a

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ encodes all the (inverse) scale lengths in the magnetic field that can be known from a ![]() $O(\epsilon ^1)$ solution, and

$O(\epsilon ^1)$ solution, and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ encodes all the additional (inverse) scale lengths in the magnetic field that can be known from a

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ encodes all the additional (inverse) scale lengths in the magnetic field that can be known from a ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ solution. It is unlikely that magnets can be much farther from the axis than any of these scale lengths. This is because in magnetostatics the field from a small-scale current structure decays rapidly as one moves away from the current; for example in slab geometry a steady sheet current

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ solution. It is unlikely that magnets can be much farther from the axis than any of these scale lengths. This is because in magnetostatics the field from a small-scale current structure decays rapidly as one moves away from the current; for example in slab geometry a steady sheet current ![]() $\propto \sin kx$ with wavenumber

$\propto \sin kx$ with wavenumber ![]() $k$ on the

$k$ on the ![]() $z=0$ plane produces a vacuum field

$z=0$ plane produces a vacuum field ![]() $\propto \exp (-|kz|)$ that is exponentially small beyond distances

$\propto \exp (-|kz|)$ that is exponentially small beyond distances ![]() $|z| > 1/|k|$. Note that these scale lengths associated with

$|z| > 1/|k|$. Note that these scale lengths associated with ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ are not directly related to scale lengths in magnetic surface shapes: surface shapes near an X-point have a radius of curvature that shrinks to zero, but the scale lengths in

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ are not directly related to scale lengths in magnetic surface shapes: surface shapes near an X-point have a radius of curvature that shrinks to zero, but the scale lengths in ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ remain non-zero on a separatrix. We therefore expect scale lengths derived from

$\boldsymbol {B}$ remain non-zero on a separatrix. We therefore expect scale lengths derived from ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ to be better indicators of the distance to a coil than scale lengths in the surface shape. ‘Worst-case’ scale lengths can be constructed by summing the squares of the matrix elements in these tensors, as in

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ to be better indicators of the distance to a coil than scale lengths in the surface shape. ‘Worst-case’ scale lengths can be constructed by summing the squares of the matrix elements in these tensors, as in

for the (squared) Frobenius norm ![]() $||\boldsymbol {\nabla } \boldsymbol {B}||^2=\sum _{i,j=1}^3 (\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B})_{i,j}^2$ and

$||\boldsymbol {\nabla } \boldsymbol {B}||^2=\sum _{i,j=1}^3 (\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B})_{i,j}^2$ and ![]() $||\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}||^2 = \sum _{i,j,k=1}^3 (\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B})_{i,j,k}^2$. These expressions are motivated at the end of this section by considering an infinite straight wire, with

$||\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}||^2 = \sum _{i,j,k=1}^3 (\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B})_{i,j,k}^2$. These expressions are motivated at the end of this section by considering an infinite straight wire, with ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ both constructed to give the distance from the wire. Since it is important in stellarators to maximize the plasma-to-coil distance, we expect that configurations with small

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ both constructed to give the distance from the wire. Since it is important in stellarators to maximize the plasma-to-coil distance, we expect that configurations with small ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ or

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ or ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ can be excluded as impractical. Both this application and the application in Giuliani et al. (Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020) motivate a calculation of

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ can be excluded as impractical. Both this application and the application in Giuliani et al. (Reference Giuliani, Wechsung, Cerfon, Stadler and Landreman2020) motivate a calculation of ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ in terms of the Garren–Boozer expansion.

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ in terms of the Garren–Boozer expansion.

To proceed, we first evaluate the vector ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ near the axis. This can be done using (2.2) in the form

$\boldsymbol {B}$ near the axis. This can be done using (2.2) in the form

where

following notation from Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991b), with ![]() $\ell '=|\partial \boldsymbol {r}_0/\partial \varphi |$. Notice

$\ell '=|\partial \boldsymbol {r}_0/\partial \varphi |$. Notice ![]() $X \sim Y \sim \epsilon ^1$,

$X \sim Y \sim \epsilon ^1$, ![]() $Z \sim \epsilon ^2$,

$Z \sim \epsilon ^2$, ![]() $\varLambda \sim \epsilon ^0$ and

$\varLambda \sim \epsilon ^0$ and ![]() $\varXi \sim \varUpsilon \sim \epsilon ^1$. Writing

$\varXi \sim \varUpsilon \sim \epsilon ^1$. Writing ![]() $\boldsymbol {B} = \boldsymbol {B}_0 + r \boldsymbol {B}_1 + r^2 \boldsymbol {B}_2 + \cdots$, and noting

$\boldsymbol {B} = \boldsymbol {B}_0 + r \boldsymbol {B}_1 + r^2 \boldsymbol {B}_2 + \cdots$, and noting ![]() $\ell ' = |G_0| / B_0$, the leading term in (3.3) is

$\ell ' = |G_0| / B_0$, the leading term in (3.3) is

The terms of next order in (3.3) give

where ![]() $B_1 = \kappa B_0 X_1$ has been employed.

$B_1 = \kappa B_0 X_1$ has been employed.

We next use the dual relations to write

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &= (\boldsymbol{\nabla} r)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial r} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\vartheta)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\vartheta} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\varphi)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\varphi} \nonumber\\ &= \frac{B^2}{(G+\iota I)r\bar{B}} \left[ \left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \times \left( \varLambda\boldsymbol{t}+\varXi\boldsymbol{n}+\varUpsilon\boldsymbol{b}\right) \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial r}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( \varLambda\boldsymbol{t}+\varXi\boldsymbol{n}+\varUpsilon\boldsymbol{b}\right) \times \left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{t}\right)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\vartheta} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.{+}\left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \times\left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}+ \frac{\partial Y}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b}+\frac{\partial Z}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\varphi}\right]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &= (\boldsymbol{\nabla} r)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial r} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\vartheta)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\vartheta} + (\boldsymbol{\nabla}\varphi)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\varphi} \nonumber\\ &= \frac{B^2}{(G+\iota I)r\bar{B}} \left[ \left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \times \left( \varLambda\boldsymbol{t}+\varXi\boldsymbol{n}+\varUpsilon\boldsymbol{b}\right) \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial r}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( \varLambda\boldsymbol{t}+\varXi\boldsymbol{n}+\varUpsilon\boldsymbol{b}\right) \times \left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{t}\right)\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\vartheta} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.{+}\left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{n}+\frac{\partial Y}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{b}+ \frac{\partial Z}{\partial r}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \times\left( \frac{\partial X}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}+ \frac{\partial Y}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b}+\frac{\partial Z}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{t}\right) \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}}{\partial\varphi}\right]. \end{align}

The terms of ![]() $O(\epsilon ^0)$ are

$O(\epsilon ^0)$ are

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{G_0 \bar{B}} \left[\ell' \left(-\frac{\partial X_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b} + \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}\right) \boldsymbol{B}_1 + \ell' (X_1 \boldsymbol{b} - Y_1 \boldsymbol{n})\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}_1}{\partial\vartheta}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.+ \left( X_1 \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial \vartheta} - Y_1 \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial \vartheta}\right) \boldsymbol{t}\frac{\textrm{d} \boldsymbol{B}_0}{\textrm{d} \varphi}\right], \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{G_0 \bar{B}} \left[\ell' \left(-\frac{\partial X_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b} + \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}\right) \boldsymbol{B}_1 + \ell' (X_1 \boldsymbol{b} - Y_1 \boldsymbol{n})\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{B}_1}{\partial\vartheta}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.+ \left( X_1 \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial \vartheta} - Y_1 \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial \vartheta}\right) \boldsymbol{t}\frac{\textrm{d} \boldsymbol{B}_0}{\textrm{d} \varphi}\right], \end{align}

where in the last term, (3.5) gives ![]() $\textrm {d} \boldsymbol {B}_0/\textrm {d}\varphi = s_G B'_0 \boldsymbol {t} + s_G B_0 \ell ' \kappa \boldsymbol {n}$. We substitute in (3.6), noting that for any functions

$\textrm {d} \boldsymbol {B}_0/\textrm {d}\varphi = s_G B'_0 \boldsymbol {t} + s_G B_0 \ell ' \kappa \boldsymbol {n}$. We substitute in (3.6), noting that for any functions

we have

and ![]() $\partial ^2 P/\partial \vartheta ^2 = -P$. We also note (A21) in LS,

$\partial ^2 P/\partial \vartheta ^2 = -P$. We also note (A21) in LS, ![]() $X_{1c}Y_{1s}-X_{1s}Y_{1c}=s_G \bar {B}/B_0$ (the condition that the first-order flux surface enclose the proper toroidal flux at each

$X_{1c}Y_{1s}-X_{1s}Y_{1c}=s_G \bar {B}/B_0$ (the condition that the first-order flux surface enclose the proper toroidal flux at each ![]() $\varphi$). We thereby obtain the final result for a general configuration as follows:

$\varphi$). We thereby obtain the final result for a general configuration as follows:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{\bar{B} \ell'} \left[ \left( X'_{1c} Y_{1s} - X'_{1s} Y_{1c} + \iota_{N0} [X_{1s} Y_{1s} + X_{1c} Y_{1c}]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n}\vphantom{\frac{\bar{B}}{B_0}}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad + \left(X_{1c} X'_{1s} - X_{1s} X'_{1c} - \frac{s_G \bar{B} \ell' \tau}{B_0} - \iota_{N0} [X_{1s}^2+X_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{n} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( Y'_{1c}Y_{1s} - Y'_{1s}Y_{1c} + \frac{s_G \bar{B} \ell' \tau}{B_0} + \iota_{N0}[Y_{1s}^2 + Y_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{b} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left. \vphantom{\frac{\bar{B}}{B_0}} +\left(X_{1c} Y'_{1s} - X_{1s} Y'_{1c} - \iota_{N0} [X_{1s}Y_{1s}+X_{1c}Y_{1c}]\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{b} \right]\notag\\ &\quad + s_G B_0 \kappa (\boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{n} + \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{t}) + \frac{ s_G B'_0}{\ell'} \boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{t}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{\bar{B} \ell'} \left[ \left( X'_{1c} Y_{1s} - X'_{1s} Y_{1c} + \iota_{N0} [X_{1s} Y_{1s} + X_{1c} Y_{1c}]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n}\vphantom{\frac{\bar{B}}{B_0}}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad + \left(X_{1c} X'_{1s} - X_{1s} X'_{1c} - \frac{s_G \bar{B} \ell' \tau}{B_0} - \iota_{N0} [X_{1s}^2+X_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{n} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( Y'_{1c}Y_{1s} - Y'_{1s}Y_{1c} + \frac{s_G \bar{B} \ell' \tau}{B_0} + \iota_{N0}[Y_{1s}^2 + Y_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{b} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left. \vphantom{\frac{\bar{B}}{B_0}} +\left(X_{1c} Y'_{1s} - X_{1s} Y'_{1c} - \iota_{N0} [X_{1s}Y_{1s}+X_{1c}Y_{1c}]\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{b} \right]\notag\\ &\quad + s_G B_0 \kappa (\boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{n} + \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{t}) + \frac{ s_G B'_0}{\ell'} \boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{t}. \end{align}

Using (A23) in LS, (which expresses how on-axis rotational transform is driven by rotating elongation, axis torsion and toroidal current), it can be seen that the ![]() $\boldsymbol {n}\boldsymbol {b}$ component and the

$\boldsymbol {n}\boldsymbol {b}$ component and the ![]() $\boldsymbol {b}\boldsymbol {n}$ component become equal when

$\boldsymbol {b}\boldsymbol {n}$ component become equal when ![]() $I_2=0$, giving the expected symmetry of

$I_2=0$, giving the expected symmetry of ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ for a vacuum field.

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ for a vacuum field.

In the case of quasisymmetry, (3.11) simplifies due to ![]() $B'_0=0$ and

$B'_0=0$ and ![]() $X_{1s}=0$, and we also have

$X_{1s}=0$, and we also have ![]() $\bar {B}=s_\psi B_0$. Thus, the

$\bar {B}=s_\psi B_0$. Thus, the ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ tensor for quasisymmetry is

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ tensor for quasisymmetry is

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{s_\psi B_0}{ \ell'} \left[ \left( X'_{1c} Y_{1s} + \iota_{N0} X_{1c} Y_{1c}\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n} +\left( - s_G s_\psi \ell' \tau - \iota_{N0} X_{1c}^2\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{n}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( Y'_{1c}Y_{1s} - Y'_{1s}Y_{1c} + s_G s_\psi \ell' \tau + \iota_{N0}[Y_{1s}^2 + Y_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{b} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left. + \left(X_{1c} Y'_{1s} - \iota_{N0} X_{1c}Y_{1c}\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{b} \right] + s_G B_0 \kappa (\boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{n} + \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{t}). \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{s_\psi B_0}{ \ell'} \left[ \left( X'_{1c} Y_{1s} + \iota_{N0} X_{1c} Y_{1c}\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{n} +\left( - s_G s_\psi \ell' \tau - \iota_{N0} X_{1c}^2\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{n}\right. \nonumber\\ &\quad +\left( Y'_{1c}Y_{1s} - Y'_{1s}Y_{1c} + s_G s_\psi \ell' \tau + \iota_{N0}[Y_{1s}^2 + Y_{1c}^2]\right) \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{b} \nonumber\\ &\quad \left. + \left(X_{1c} Y'_{1s} - \iota_{N0} X_{1c}Y_{1c}\right) \boldsymbol{b}\boldsymbol{b} \right] + s_G B_0 \kappa (\boldsymbol{t}\boldsymbol{n} + \boldsymbol{n}\boldsymbol{t}). \end{align} Analogously to (3.7)–(3.8), we can evaluate the ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ tensor as well. To leading order,

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } \boldsymbol {B}$ tensor as well. To leading order,

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{G_0 \bar{B}} \left[\ell' \left(-\frac{\partial X_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b} + \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}\right) (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_1 + \ell' (X_1 \boldsymbol{b} - Y_1 \boldsymbol{n})\frac{\partial (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_1}{\partial\vartheta} \right. \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.+ \left( X_1 \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial \vartheta} - Y_1 \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial \vartheta}\right) \boldsymbol{t} \frac{\partial (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_0}{\partial \varphi}\right]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\nabla\nabla} \boldsymbol{B} &\approx \frac{B_0^2}{G_0 \bar{B}} \left[\ell' \left(-\frac{\partial X_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{b} + \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial\vartheta}\boldsymbol{n}\right) (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_1 + \ell' (X_1 \boldsymbol{b} - Y_1 \boldsymbol{n})\frac{\partial (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_1}{\partial\vartheta} \right. \nonumber\\ &\quad \left.+ \left( X_1 \frac{\partial Y_1}{\partial \vartheta} - Y_1 \frac{\partial X_1}{\partial \vartheta}\right) \boldsymbol{t} \frac{\partial (\boldsymbol{\nabla} \boldsymbol{B})_0}{\partial \varphi}\right]. \end{align}

The result is too lengthy to write here, but it can be found in a Mathematica notebook in Landreman (Reference Landreman2020a). The result depends on ![]() $X_2$,

$X_2$, ![]() $Y_2$ and

$Y_2$ and ![]() $Z_2$.

$Z_2$.

For reference, we note the values of ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and

$\boldsymbol {\nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ in the limit of an axisymmetric and purely toroidal vacuum field, which is the field of an infinite straight vertical wire at major radius

$\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla }\boldsymbol {B}$ in the limit of an axisymmetric and purely toroidal vacuum field, which is the field of an infinite straight vertical wire at major radius ![]() $R=0$. This limit can be used for verification and to derive figures of merit such as (3.1)–(3.2), the equivalent distance to a coil. The field is

$R=0$. This limit can be used for verification and to derive figures of merit such as (3.1)–(3.2), the equivalent distance to a coil. The field is ![]() $\boldsymbol {B} = s_G \mu _0 I \boldsymbol {t} / (2 {\rm \pi} R)$, where

$\boldsymbol {B} = s_G \mu _0 I \boldsymbol {t} / (2 {\rm \pi} R)$, where ![]() $I>0$ is the current in the wire,

$I>0$ is the current in the wire, ![]() $R$ is the distance from the wire and

$R$ is the distance from the wire and ![]() $\boldsymbol {t}=\boldsymbol {e}_\phi$ is the unit vector in the direction of the standard cylindrical angle

$\boldsymbol {t}=\boldsymbol {e}_\phi$ is the unit vector in the direction of the standard cylindrical angle ![]() $\phi$. Note also

$\phi$. Note also ![]() $\boldsymbol {n}=-\boldsymbol {e}_R$. Then

$\boldsymbol {n}=-\boldsymbol {e}_R$. Then

consistent with the appropriate limit of (3.12) (![]() $d/d\varphi =0$,

$d/d\varphi =0$, ![]() $\tau =0$,

$\tau =0$, ![]() $\iota _{N0}=0$). Forming the squared Frobenius norm of this expression and solving for

$\iota _{N0}=0$). Forming the squared Frobenius norm of this expression and solving for ![]() $R$ gives

$R$ gives ![]() $R = L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ where

$R = L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ where ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ is the figure of merit (3.1). Similarly,

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ is the figure of merit (3.1). Similarly,

Squaring and solving for ![]() $R$ gives

$R$ gives ![]() $R = L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ where

$R = L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ where ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ is the expression in (3.2).

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ is the expression in (3.2).

For this case of a purely toroidal ![]() $B\propto 1/R$ field, the same

$B\propto 1/R$ field, the same ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ can be produced in an axisymmetric toroidal domain by a poloidal sheet current on the domain boundary. Hence the currents can be moved closer to an evaluation point at some fixed

$\boldsymbol {B}$ can be produced in an axisymmetric toroidal domain by a poloidal sheet current on the domain boundary. Hence the currents can be moved closer to an evaluation point at some fixed ![]() $R>0$ without changing

$R>0$ without changing ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ or

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ or ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$. This example illustrates that for a given field, there is no unique distance to a coil. The best we can hope to compute from a given

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$. This example illustrates that for a given field, there is no unique distance to a coil. The best we can hope to compute from a given ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$ is a maximum distance to a current, reflecting the distance to a singularity in the exterior (Greene Reference Greene1965). In this axisymmetic example, where there must be current through the donut hole of the toroidal region where

$\boldsymbol {B}$ is a maximum distance to a current, reflecting the distance to a singularity in the exterior (Greene Reference Greene1965). In this axisymmetic example, where there must be current through the donut hole of the toroidal region where ![]() $B\propto 1/R$,

$B\propto 1/R$, ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ give the correct maximum possible distance to a current.

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ give the correct maximum possible distance to a current.

Figure 1 shows the scale lengths ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ for the five

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ for the five ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ quasisymmetric configurations discussed in LS.

Colours and legend text in the figure refer to section numbers in LS, each representing a different stellarator configuration. The scale lengths are normalized to the major radius to yield dimensionless figures of merit. By design, this normalized measure is 1 for a purely toroidal field, and small values are undesirable. The examples from sections 5.1–5.3 are quasi-axisymmetric, while the examples from sections 5.4 and 5.5 are quasihelically symmetric. The example of section 5.5 lacks stellarator symmetry, while the other examples are stellarator symmetric. Therefore the two curves for this example lack reflection symmetry about

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ quasisymmetric configurations discussed in LS.

Colours and legend text in the figure refer to section numbers in LS, each representing a different stellarator configuration. The scale lengths are normalized to the major radius to yield dimensionless figures of merit. By design, this normalized measure is 1 for a purely toroidal field, and small values are undesirable. The examples from sections 5.1–5.3 are quasi-axisymmetric, while the examples from sections 5.4 and 5.5 are quasihelically symmetric. The example of section 5.5 lacks stellarator symmetry, while the other examples are stellarator symmetric. Therefore the two curves for this example lack reflection symmetry about ![]() $n_{fp}\varphi ={\rm \pi}$, whereas the curves for the stellarator-symmetric examples do have this reflection symmetry. The example of section 5.5 has quite strong shaping, as is evident in figure 17 of LS. Therefore it is not surprising that this example has significantly smaller values for the normalized scale lengths compared with the other examples. This initial evidence is at least suggestive that

$n_{fp}\varphi ={\rm \pi}$, whereas the curves for the stellarator-symmetric examples do have this reflection symmetry. The example of section 5.5 has quite strong shaping, as is evident in figure 17 of LS. Therefore it is not surprising that this example has significantly smaller values for the normalized scale lengths compared with the other examples. This initial evidence is at least suggestive that ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ may be useful as proxies for the complexity of a magnetic configuration. Specifically, noting that

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ may be useful as proxies for the complexity of a magnetic configuration. Specifically, noting that ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ are somewhat independent, and that the shortest scale length dominates, we conjecture that small values of

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ are somewhat independent, and that the shortest scale length dominates, we conjecture that small values of ![]() $\min (L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B},\ L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B})$ are correlated with high coil complexity. Further study involving coil optimization is needed to verify this conjecture. Note that

$\min (L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B},\ L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B})$ are correlated with high coil complexity. Further study involving coil optimization is needed to verify this conjecture. Note that ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla } B}$ and ![]() $L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ can be evaluated in under 1 ms for reasonable resolutions, roughly four orders of magnitude faster than even the fastest calculations of coil shapes with current–potential methods like REGCOIL (Landreman Reference Landreman2017).

$L_{\boldsymbol {\nabla \nabla } B}$ can be evaluated in under 1 ms for reasonable resolutions, roughly four orders of magnitude faster than even the fastest calculations of coil shapes with current–potential methods like REGCOIL (Landreman Reference Landreman2017).

Figure 1. Scale lengths in the magnetic field, indicating measures of the effective distance to an electromagnetic coil, evaluated for the five examples in Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019). Section numbers in the legend refer to this earlier paper. Both of the scale lengths (3.1) and (3.2) are shown.

4. Minimum aspect ratio without intersecting surfaces

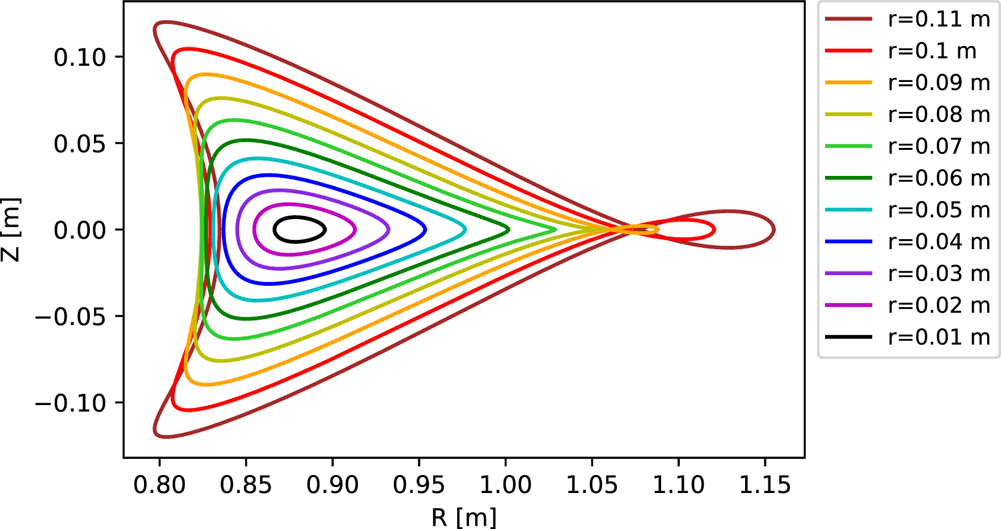

When a stellarator configuration is constructed to ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ using the near-axis expansion, a common problem is the following. The triangularity of the constructed boundary surface grows with

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ using the near-axis expansion, a common problem is the following. The triangularity of the constructed boundary surface grows with ![]() $r$, as does the shift of the surface centroid compared with the magnetic axis. For

$r$, as does the shift of the surface centroid compared with the magnetic axis. For ![]() $r$ beyond a critical value

$r$ beyond a critical value ![]() $r_c$, the surface can begin to self-intersect, or the surfaces may no longer be nested, as shown in figure 2. These intersections and overlaps of the surfaces are not physically realizable, but rather are an indication that the small-

$r_c$, the surface can begin to self-intersect, or the surfaces may no longer be nested, as shown in figure 2. These intersections and overlaps of the surfaces are not physically realizable, but rather are an indication that the small-![]() $r$ expansion has broken down. These problems with the surface geometry put a lower limit on the aspect ratio at which boundary surfaces can be constructed by the near-axis method. Therefore, it is useful to be able to calculate

$r$ expansion has broken down. These problems with the surface geometry put a lower limit on the aspect ratio at which boundary surfaces can be constructed by the near-axis method. Therefore, it is useful to be able to calculate ![]() $r_c$.

$r_c$.

Figure 2. Several unphysical behaviours can arise in the constructed flux surface shapes for sufficiently large minor radius ![]() $r$. In the example here, showing the

$r$. In the example here, showing the ![]() $\phi =0$ cross-section of the configuration of § 4.3, each surface intersects itself on the large-

$\phi =0$ cross-section of the configuration of § 4.3, each surface intersects itself on the large-![]() $R$ side when

$R$ side when ![]() $r>0.085$ m, and the surfaces are not properly nested on the small-

$r>0.085$ m, and the surfaces are not properly nested on the small-![]() $R$ side for

$R$ side for ![]() $r>0.077$ m.

$r>0.077$ m.

In effect, ![]() $r_c$ is a convenient summary of how rapidly the coefficients of the

$r_c$ is a convenient summary of how rapidly the coefficients of the ![]() $r$ expansion increase with the order in the expansion. The

$r$ expansion increase with the order in the expansion. The ![]() $(X_j, Y_j, Z_j)$ coefficients tend to increase with

$(X_j, Y_j, Z_j)$ coefficients tend to increase with ![]() $j$, since in the Garren–Boozer equations the order-

$j$, since in the Garren–Boozer equations the order-![]() $j$ terms depend on the

$j$ terms depend on the ![]() $d/d\varphi$ derivatives of the order-

$d/d\varphi$ derivatives of the order-![]() $(\,j-1)$ terms. This increase with

$(\,j-1)$ terms. This increase with ![]() $j$ limits the radius of convergence of the expansion in

$j$ limits the radius of convergence of the expansion in ![]() $r$. When

$r$. When ![]() $r_c$ is small, the coefficients increase rapidly with order so the expansion is accurate only for small

$r_c$ is small, the coefficients increase rapidly with order so the expansion is accurate only for small ![]() $r$. We wish to find solutions of the near-axis equations for which the coefficients do not increase rapidly with order, so the expansion is accurate for relatively large

$r$. We wish to find solutions of the near-axis equations for which the coefficients do not increase rapidly with order, so the expansion is accurate for relatively large ![]() $r$. Hence, we seek solutions with large

$r$. Hence, we seek solutions with large ![]() $r_c$.

$r_c$.

For quasisymmetric configurations, this critical value ![]() $r_c$ for singularity is also useful as a measure of the accuracy of quasisymmetry. This is because the construction achieves quasisymmetry through

$r_c$ for singularity is also useful as a measure of the accuracy of quasisymmetry. This is because the construction achieves quasisymmetry through ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ but not at

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ but not at ![]() $O(\epsilon ^3)$, so quasisymmetry is not accurately obtained at values of

$O(\epsilon ^3)$, so quasisymmetry is not accurately obtained at values of ![]() $r$ for which the

$r$ for which the ![]() $O(\epsilon ^3)$ terms matter. One can expect the quantities

$O(\epsilon ^3)$ terms matter. One can expect the quantities ![]() $\{B_j, X_j, Y_j, Z_j\}$ at each order

$\{B_j, X_j, Y_j, Z_j\}$ at each order ![]() $j$ to all be roughly comparable in magnitude since they are related by the equations at each order of the expansion, e.g. (A32)–(A48) of LS. The

$j$ to all be roughly comparable in magnitude since they are related by the equations at each order of the expansion, e.g. (A32)–(A48) of LS. The ![]() $O(\epsilon ^3)$ terms in the shape evidently matter when

$O(\epsilon ^3)$ terms in the shape evidently matter when ![]() $r \sim r_c$, for then the

$r \sim r_c$, for then the ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ shape is unphysical. Therefore, configurations with large

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ shape is unphysical. Therefore, configurations with large ![]() $r_c$ can be expected to have good quasisymmetry throughout a larger volume than configurations with small

$r_c$ can be expected to have good quasisymmetry throughout a larger volume than configurations with small ![]() $r_c$. Motivated by these reasons above, in this section we seek a method to calculate

$r_c$. Motivated by these reasons above, in this section we seek a method to calculate ![]() $r_c$.

$r_c$.

Considering the type of singularity on the large-![]() $R$ side of figure 2, the sharp edge in the surface shape is reminiscent of the X-point in a diverted tokamak. It may therefore be possible to take advantage of this kind of singularity to design a stellarator divertor. We will not attempt to pursue this possibility here.

$R$ side of figure 2, the sharp edge in the surface shape is reminiscent of the X-point in a diverted tokamak. It may therefore be possible to take advantage of this kind of singularity to design a stellarator divertor. We will not attempt to pursue this possibility here.

4.1. Problem formulation

The condition for self-intersection or overlap of the flux surfaces, i.e. constant-![]() $r$ surfaces, is

$r$ surfaces, is ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$, where

$\sqrt {g}=0$, where ![]() $\sqrt {g}$ is the Jacobian,

$\sqrt {g}$ is the Jacobian,

We define ![]() $r_c$ as the minimum positive value of

$r_c$ as the minimum positive value of ![]() $r$ such that

$r$ such that ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$. Since this definition has the form of a constrained optimization problem, we introduce a Lagrange multiplier

$\sqrt {g}=0$. Since this definition has the form of a constrained optimization problem, we introduce a Lagrange multiplier ![]() $\lambda$, and seek stationary points of the Lagrangian

$\lambda$, and seek stationary points of the Lagrangian ![]() $\mathcal {L}{(\lambda ,r,\vartheta ,\varphi )} = r + \lambda \sqrt {g}$. Variation with respect to

$\mathcal {L}{(\lambda ,r,\vartheta ,\varphi )} = r + \lambda \sqrt {g}$. Variation with respect to ![]() $\lambda$ recovers the constraint

$\lambda$ recovers the constraint ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$. Variation of

$\sqrt {g}=0$. Variation of ![]() $\mathcal {L}$ with respect to the spatial coordinates yields

$\mathcal {L}$ with respect to the spatial coordinates yields

Equation (4.2) effectively determines ![]() $\lambda$, and will not be needed. In practice, since the shape coefficients

$\lambda$, and will not be needed. In practice, since the shape coefficients ![]() $\{X,Y,Z\}$ are available on a grid in

$\{X,Y,Z\}$ are available on a grid in ![]() $\varphi$, it is convenient to replace (4.4) with minimization over the same

$\varphi$, it is convenient to replace (4.4) with minimization over the same ![]() $\varphi$ grid, as follows. We define

$\varphi$ grid, as follows. We define ![]() $\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$ as the solution of

$\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$ as the solution of ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ and (4.3) at given

$\sqrt {g}=0$ and (4.3) at given ![]() $\varphi$, we can evaluate

$\varphi$, we can evaluate ![]() $\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$ on the numerical grid in

$\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$ on the numerical grid in ![]() $\varphi$, and we then identify

$\varphi$, and we then identify ![]() $r_c = \min _\varphi \hat {r}_c(\varphi )$. The key task then is to compute

$r_c = \min _\varphi \hat {r}_c(\varphi )$. The key task then is to compute ![]() $\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$.

$\hat {r}_c(\varphi )$.

To this end, we substitute the position vector (2.4) and expansions (2.6) and (2.9) into (4.1), using (2.5a–d). If the expansion for ![]() $\{X,Y,Z\}$ is truncated after

$\{X,Y,Z\}$ is truncated after ![]() $\{X_1,Y_1,Z_1\}$, corresponding to the

$\{X_1,Y_1,Z_1\}$, corresponding to the ![]() $O(\epsilon )$ construction, then

$O(\epsilon )$ construction, then ![]() $\sqrt {g} = (1-r X_1 \kappa )r s_G \bar {B} \ell ' / B_0$, and the solution of

$\sqrt {g} = (1-r X_1 \kappa )r s_G \bar {B} \ell ' / B_0$, and the solution of ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ and

$\sqrt {g}=0$ and ![]() $\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0$ gives

$\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0$ gives ![]() $\hat {r}_c(\varphi ) = 1/(\kappa \sqrt {X_{1s}^2 + X_{1c}^2})$. For the rest of § 4 we will consider the more complicated problem of the

$\hat {r}_c(\varphi ) = 1/(\kappa \sqrt {X_{1s}^2 + X_{1c}^2})$. For the rest of § 4 we will consider the more complicated problem of the ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ construction, in which the expansion for

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ construction, in which the expansion for ![]() $\{X,Y,Z\}$ is truncated after

$\{X,Y,Z\}$ is truncated after ![]() $\{X_2,Y_2,Z_2\}$. In this case, the product in (4.1) involving three copies of the position vector includes terms scaling as

$\{X_2,Y_2,Z_2\}$. In this case, the product in (4.1) involving three copies of the position vector includes terms scaling as ![]() $r^1$ through

$r^1$ through ![]() $r^5$,

$r^5$,

\begin{equation} \sqrt{g}=r \sum_{j=0}^4 r^j g_j(\vartheta,\varphi) \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sqrt{g}=r \sum_{j=0}^4 r^j g_j(\vartheta,\varphi) \end{equation}

where ![]() $g_0=g_0(\varphi )$ is independent of

$g_0=g_0(\varphi )$ is independent of ![]() $\vartheta$,

$\vartheta$,

analogous to (2.6). We find ![]() $g_0=(X_{1c}Y_{1s} -X_{1s}Y_{1c})\ell '= s_G \bar {B} \ell ' / B_0$ and

$g_0=(X_{1c}Y_{1s} -X_{1s}Y_{1c})\ell '= s_G \bar {B} \ell ' / B_0$ and ![]() $g_{1s,c} = -2 s_G \bar {B}\ell ' B_{1s,c}/B_0^2$. These expressions can be derived using (A21) and (A32)–(A33) in LS, which express equality of the

$g_{1s,c} = -2 s_G \bar {B}\ell ' B_{1s,c}/B_0^2$. These expressions can be derived using (A21) and (A32)–(A33) in LS, which express equality of the ![]() $\boldsymbol {t}$ components of the covariant and contravariant representations of

$\boldsymbol {t}$ components of the covariant and contravariant representations of ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$. These results for

$\boldsymbol {B}$. These results for ![]() $g_0$ and

$g_0$ and ![]() $g_1$ can also be derived by expanding

$g_1$ can also be derived by expanding ![]() $(G+\iota I)r \bar {B}/ B^2$, which is equal to

$(G+\iota I)r \bar {B}/ B^2$, which is equal to ![]() $\sqrt {g}$ if all orders in the expansion are retained. However, since the expansion is truncated after

$\sqrt {g}$ if all orders in the expansion are retained. However, since the expansion is truncated after ![]() $\{X_2,Y_2,Z_2\}$,

$\{X_2,Y_2,Z_2\}$, ![]() $g_j$ does not equal the corresponding term in the expansion of

$g_j$ does not equal the corresponding term in the expansion of ![]() $(G+\iota I)r \bar {B}/ B^2$ for

$(G+\iota I)r \bar {B}/ B^2$ for ![]() $j \ge 2$. Explicit expressions for

$j \ge 2$. Explicit expressions for ![]() $g_2$ are given in appendix A.

$g_2$ are given in appendix A.

At each ![]() $\varphi$, the equations

$\varphi$, the equations ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ and

$\sqrt {g}=0$ and ![]() $\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta$ then give two equations for the two unknowns

$\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta$ then give two equations for the two unknowns ![]() $\vartheta$ and

$\vartheta$ and ![]() $r=\hat {r}_c$. In principle this nonlinear system could be solved numerically using Newton's method. As with any such nonlinear problem, it is hard to ensure that all possible solutions are found, since the numerical solution depends on an initial guess. However, we are primarily interested in the smallest positive solution for

$r=\hat {r}_c$. In principle this nonlinear system could be solved numerically using Newton's method. As with any such nonlinear problem, it is hard to ensure that all possible solutions are found, since the numerical solution depends on an initial guess. However, we are primarily interested in the smallest positive solution for ![]() $\hat {r}_c$, which is the root that sets the limit on minimum aspect ratio. In the next subsection we show how this smallest positive root can be found more robustly using an asymptotic approach. The approximate root location computed in the next subsection can serve as a good initial guess for Newton iteration if a more accurate value of

$\hat {r}_c$, which is the root that sets the limit on minimum aspect ratio. In the next subsection we show how this smallest positive root can be found more robustly using an asymptotic approach. The approximate root location computed in the next subsection can serve as a good initial guess for Newton iteration if a more accurate value of ![]() $r_c$ is desired.

$r_c$ is desired.

4.2. Robust solution

Since we seek solutions of ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ and

$\sqrt {g}=0$ and ![]() $\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0$ for small

$\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0$ for small ![]() $r$, we keep only the leading three orders in

$r$, we keep only the leading three orders in ![]() $\sqrt {g}$:

$\sqrt {g}$: ![]() $\sqrt {g} \approx r(g_0+r g_1 + r^2 g_2)$. Then (4.3) can be written as

$\sqrt {g} \approx r(g_0+r g_1 + r^2 g_2)$. Then (4.3) can be written as

Using this result to eliminate ![]() $r$ in

$r$ in ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$, we obtain

$\sqrt {g}=0$, we obtain

where

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} K_0 & = 2 g_{20}(g_{1c}^2+g_{1s}^2)+8 g_0(g_{2c}^2+g_{2s}^2)+ 3 g_{2c}(g_{1s}^2-g_{1c}^2) - 6 g_{1c} g_{1s} g_{2s}, \\ K_{2s} & = 2 g_{2s} (g_{1c}^2 + g_{1s}^2) -4 g_{1s} g_{1c} g_{20}, \\ K_{2c} & = 2 g_{20} (g_{1s}^2-g_{1c}^2) + 2 g_{2c} (g_{1s}^2+g_{1c}^2), \\ K_{4s} & = g_{2s}(g_{1c}^2-g_{1s}^2) + 2 g_{1c} g_{1s} g_{2c} - 16 g_0 g_{2c} g_{2s}, \\ K_{4c} & = g_{2c}(g_{1c}^2-g_{1s}^2) + 8 g_0 (g_{2s}^2-g_{2c}^2) -2 g_{1s}g_{1c}g_{2s}. \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} K_0 & = 2 g_{20}(g_{1c}^2+g_{1s}^2)+8 g_0(g_{2c}^2+g_{2s}^2)+ 3 g_{2c}(g_{1s}^2-g_{1c}^2) - 6 g_{1c} g_{1s} g_{2s}, \\ K_{2s} & = 2 g_{2s} (g_{1c}^2 + g_{1s}^2) -4 g_{1s} g_{1c} g_{20}, \\ K_{2c} & = 2 g_{20} (g_{1s}^2-g_{1c}^2) + 2 g_{2c} (g_{1s}^2+g_{1c}^2), \\ K_{4s} & = g_{2s}(g_{1c}^2-g_{1s}^2) + 2 g_{1c} g_{1s} g_{2c} - 16 g_0 g_{2c} g_{2s}, \\ K_{4c} & = g_{2c}(g_{1c}^2-g_{1s}^2) + 8 g_0 (g_{2s}^2-g_{2c}^2) -2 g_{1s}g_{1c}g_{2s}. \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

We now convert (4.9) to an equation for the roots of a polynomial, since all roots of such equations can be computed robustly using the companion matrix method described below. Introducing ![]() $w = \sin 2\vartheta$, then

$w = \sin 2\vartheta$, then ![]() $\cos 2\vartheta = \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ where

$\cos 2\vartheta = \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ where ![]() $\varpi = \pm 1$. Also,

$\varpi = \pm 1$. Also, ![]() $\sin 4\vartheta = 2 w \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ and

$\sin 4\vartheta = 2 w \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ and ![]() $\cos 4\vartheta = 1-2 w^2$. Using these results to eliminate the trigonometric functions, (4.9) can be written as

$\cos 4\vartheta = 1-2 w^2$. Using these results to eliminate the trigonometric functions, (4.9) can be written as

where

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} P_4 & = 4 K_{4c}^2 + 4 K_{4s}^2,\\ P_3 & = 4 K_{4s} K_{2c} - 4 K_{4c} K_{2s}, \\ P_2 & = K_{2s}^2+K_{2c}^2 - 4 K_0 K_{4c} - 4 K_{4c}^2 - 4 K_{4s}^2, \\ P_1 & = 2 K_0 K_{2s} +2 K_{4c} K_{2s} - 4 K_{4s} K_{2c}, \\ P_0 & = (K_0 + K_{4c})^2 - K_{2c}^2. \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left.\begin{aligned} P_4 & = 4 K_{4c}^2 + 4 K_{4s}^2,\\ P_3 & = 4 K_{4s} K_{2c} - 4 K_{4c} K_{2s}, \\ P_2 & = K_{2s}^2+K_{2c}^2 - 4 K_0 K_{4c} - 4 K_{4c}^2 - 4 K_{4s}^2, \\ P_1 & = 2 K_0 K_{2s} +2 K_{4c} K_{2s} - 4 K_{4s} K_{2c}, \\ P_0 & = (K_0 + K_{4c})^2 - K_{2c}^2. \end{aligned}\right\} \end{equation}

The solutions ![]() $w$ of (4.11) can be computed robustly by finding the eigenvalues of the companion matrix

$w$ of (4.11) can be computed robustly by finding the eigenvalues of the companion matrix

\begin{equation} M = \begin{pmatrix} -P_3/P_4 & -P_2/P_4 & -P_1/P_4 & -P_0/P_4 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} M = \begin{pmatrix} -P_3/P_4 & -P_2/P_4 & -P_1/P_4 & -P_0/P_4 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \end{equation}

a matrix constructed such that its characteristic polynomial ![]() $\det |M - wI|$ (for identity matrix

$\det |M - wI|$ (for identity matrix ![]() $I$) is proportional to the original polynomial (4.11).

$I$) is proportional to the original polynomial (4.11).

Then for each real solution ![]() $w$,

$w$, ![]() $\varpi$ can in principle be computed from (4.9) in the form

$\varpi$ can in principle be computed from (4.9) in the form

where the square of the right-hand side is 1 due to (4.11). Thus, precisely one of the two choices for ![]() $\varpi$ is consistent with each real root

$\varpi$ is consistent with each real root ![]() $w$. Due to possible precision loss in the expression (4.14) in finite-precision arithmetic, it is more convenient in practice to select

$w$. Due to possible precision loss in the expression (4.14) in finite-precision arithmetic, it is more convenient in practice to select ![]() $\varpi$ as the element of

$\varpi$ as the element of ![]() $\{-1,1\}$ that minimizes the residual in (4.9). With

$\{-1,1\}$ that minimizes the residual in (4.9). With ![]() $\cos 2\vartheta = \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ now known,

$\cos 2\vartheta = \varpi \sqrt {1-w^2}$ now known, ![]() $\cos \vartheta$ can be computed from

$\cos \vartheta$ can be computed from ![]() $\varsigma \sqrt {(1+\cos 2\vartheta )/2}$, with

$\varsigma \sqrt {(1+\cos 2\vartheta )/2}$, with ![]() $\varsigma =\pm 1$. Note that

$\varsigma =\pm 1$. Note that ![]() $\sin \vartheta$ can be computed from

$\sin \vartheta$ can be computed from ![]() $(\sin 2\vartheta )/(2 \cos \vartheta )$. The two choices of

$(\sin 2\vartheta )/(2 \cos \vartheta )$. The two choices of ![]() $\varsigma$ correspond to a pair of solutions of

$\varsigma$ correspond to a pair of solutions of ![]() $\{ \sqrt {g}=0,\ \partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0\}$ in which

$\{ \sqrt {g}=0,\ \partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0\}$ in which ![]() $r$ differs by a factor of

$r$ differs by a factor of ![]() $-1$, i.e. the two choices represent two representations

$-1$, i.e. the two choices represent two representations ![]() $(\vartheta _0,\ r_0)$ and

$(\vartheta _0,\ r_0)$ and ![]() $(\vartheta _0+{\rm \pi} ,\ -r_0)$ of the same physical point. It is no loss of generality to consider only the solution with positive

$(\vartheta _0+{\rm \pi} ,\ -r_0)$ of the same physical point. It is no loss of generality to consider only the solution with positive ![]() $r$. One can compute

$r$. One can compute ![]() $r$ from (4.8), or from

$r$ from (4.8), or from ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ if the denominator of (4.8) vanishes. The smallest positive solution for

$\sqrt {g}=0$ if the denominator of (4.8) vanishes. The smallest positive solution for ![]() $r$ derived from the various roots of (4.11) is then

$r$ derived from the various roots of (4.11) is then ![]() $\hat {r}_c$.

$\hat {r}_c$.

By this method, the nonlinear equations for ![]() $\hat {r}_c$ can be solved without any need for an initial guess. The resulting value of

$\hat {r}_c$ can be solved without any need for an initial guess. The resulting value of ![]() $\hat {r}_c$ can either be used directly as a good approximation for the exact solution (by which we mean a solution of

$\hat {r}_c$ can either be used directly as a good approximation for the exact solution (by which we mean a solution of ![]() $\{ \sqrt {g}=0,\ \partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0\}$ in which

$\{ \sqrt {g}=0,\ \partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta =0\}$ in which ![]() $g_4$ and

$g_4$ and ![]() $g_5$ are retained in

$g_5$ are retained in ![]() $\sqrt {g}$), or it can be used as an initial guess for Newton iteration to find the exact solution.

$\sqrt {g}$), or it can be used as an initial guess for Newton iteration to find the exact solution.

4.3. Example

Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate the methods of this section for an example quasi-axisymmetric configuration. The configuration is constructed using the ![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$ equations, with axis shape

$O(\epsilon ^2)$ equations, with axis shape ![]() $R [\mathrm {m}]= 1 - 0.12 \cos (2\phi )$ and

$R [\mathrm {m}]= 1 - 0.12 \cos (2\phi )$ and ![]() $Z [\mathrm {m}]= 0.12 \sin (2\phi )$. The other input parameters for the construction were

$Z [\mathrm {m}]= 0.12 \sin (2\phi )$. The other input parameters for the construction were ![]() $\bar {\eta } = -0.7$ m

$\bar {\eta } = -0.7$ m![]() $^{-1}$,

$^{-1}$, ![]() $\sigma (0)=0$,

$\sigma (0)=0$, ![]() $I_2=0$,

$I_2=0$, ![]() $p_2=0$,

$p_2=0$, ![]() $B_{2s}=0$ and

$B_{2s}=0$ and ![]() $B_{2c} = -0.5$ T

$B_{2c} = -0.5$ T![]() $/$m

$/$m![]() $^{2}$. This configuration was chosen since multiple types of singularities can be seen in the

$^{2}$. This configuration was chosen since multiple types of singularities can be seen in the ![]() $\phi =0$ cross-section, as shown in figure 2. On the large-

$\phi =0$ cross-section, as shown in figure 2. On the large-![]() $R$ side, each magnetic surface with sufficiently large

$R$ side, each magnetic surface with sufficiently large ![]() $r$ crosses through itself, and on the small-

$r$ crosses through itself, and on the small-![]() $R$ side, the surfaces are not simply nested beyond a critical

$R$ side, the surfaces are not simply nested beyond a critical ![]() $r$.

$r$.

Figure 3 shows the value of ![]() $\hat {r}_c$ computed using the method of § 4.2 for this example. The solution found is the one at the small-

$\hat {r}_c$ computed using the method of § 4.2 for this example. The solution found is the one at the small-![]() $R$ side, occurring at

$R$ side, occurring at ![]() $\hat {r}_c=0.0762$ m in the

$\hat {r}_c=0.0762$ m in the ![]() $\varphi =0$ plane, a slightly smaller value of

$\varphi =0$ plane, a slightly smaller value of ![]() $r$ than the singularity at the large-

$r$ than the singularity at the large-![]() $R$ side. At each grid point in

$R$ side. At each grid point in ![]() $\varphi$, this solution is used as an initial guess for a solution of the full problem from § 4.1 using Newton's method. Newton's method converges to machine precision at all grid points, and the solution is plotted on the same graph. In this case the Newton solution barely differs from the robust approximate solution, with a solution

$\varphi$, this solution is used as an initial guess for a solution of the full problem from § 4.1 using Newton's method. Newton's method converges to machine precision at all grid points, and the solution is plotted on the same graph. In this case the Newton solution barely differs from the robust approximate solution, with a solution ![]() $\hat {r}_c=0.0767$ m in the

$\hat {r}_c=0.0767$ m in the ![]() $\varphi =0$ plane. For other magnetic configurations in which the minimum aspect ratio is much lower, significant differences can arise between the robust and Newton solutions for

$\varphi =0$ plane. For other magnetic configurations in which the minimum aspect ratio is much lower, significant differences can arise between the robust and Newton solutions for ![]() $r_c$. Nevertheless, the robust method is found to be extremely accurate (as in the example shown) when the minimum aspect ratio is large, making it useful for screening out such configurations.

$r_c$. Nevertheless, the robust method is found to be extremely accurate (as in the example shown) when the minimum aspect ratio is large, making it useful for screening out such configurations.

4.4. Tokamak equilibrium limit

In both tokamaks and stellarators, an equilibrium beta limit exists associated with an X-point approaching and reaching the plasma boundary (Mukhovatov & Shafranov Reference Mukhovatov and Shafranov1971; Freidberg Reference Freidberg2014). As the method of §§ 4.1 and 4.2 finds singularities in the flux surface geometry, we might expect that this method can calculate this equilibrium beta limit. Here we show that this is indeed true for a high-aspect-ratio tokamak. This correspondence gives added meaning and value to the figure of merit ![]() $r_c$ in §§ 4.1 and 4.2.

$r_c$ in §§ 4.1 and 4.2.

For this calculation we use the ‘high-![]() $\beta$ tokamak’ ordering, (6.92) of Freidberg (Reference Freidberg2014):

$\beta$ tokamak’ ordering, (6.92) of Freidberg (Reference Freidberg2014): ![]() $\epsilon \ll 1$ where

$\epsilon \ll 1$ where ![]() $\epsilon = a/R$,

$\epsilon = a/R$, ![]() $\mu _0 p_0 / B_0^2 \sim \epsilon$ and

$\mu _0 p_0 / B_0^2 \sim \epsilon$ and ![]() $\iota \sim 1$. Since axisymmetry is considered here, the Garren–Boozer equations in this case are given in appendix B. We consider a pressure profile

$\iota \sim 1$. Since axisymmetry is considered here, the Garren–Boozer equations in this case are given in appendix B. We consider a pressure profile ![]() $p(r) = p_0 + r^2 p_2$ such that

$p(r) = p_0 + r^2 p_2$ such that ![]() $p(a)=0$ at the plasma boundary

$p(a)=0$ at the plasma boundary ![]() $r=a$, so

$r=a$, so ![]() $p_2 = -p_0 / a^2$. Then using (B 1), it follows that

$p_2 = -p_0 / a^2$. Then using (B 1), it follows that

We limit our attention to up–down symmetric geometry, so ![]() $\sigma =0$. The near-axis solutions have a degree of freedom

$\sigma =0$. The near-axis solutions have a degree of freedom ![]() $B_{2c}$ reflecting the freedom in triangularity, and for simplicity we will limit attention to the case of zero triangularity, which can be expressed as

$B_{2c}$ reflecting the freedom in triangularity, and for simplicity we will limit attention to the case of zero triangularity, which can be expressed as

for some flux functions ![]() ${\rm \Delta} (r)$,

${\rm \Delta} (r)$, ![]() $b(r)$ and

$b(r)$ and ![]() $c(r)$. This equation is independent of the near-axis expansion. To demand consistency between (4.16) and the near-axis equations, we take

$c(r)$. This equation is independent of the near-axis expansion. To demand consistency between (4.16) and the near-axis equations, we take ![]() ${\rm \Delta} (r)$,

${\rm \Delta} (r)$, ![]() $b(r)$ and

$b(r)$ and ![]() $c(r)$ to be polynomials and equate terms at each order. The

$c(r)$ to be polynomials and equate terms at each order. The ![]() $r^2 \cos ^2\vartheta$ terms give the leading (constant) term of

$r^2 \cos ^2\vartheta$ terms give the leading (constant) term of ![]() $b$ to be

$b$ to be ![]() $X_{1c}^2/Y_{1s}^2$. Then the

$X_{1c}^2/Y_{1s}^2$. Then the ![]() $r^3 \cos 3\vartheta$ terms give

$r^3 \cos 3\vartheta$ terms give

This result, with (B 11) and (B 6), determines ![]() $B_{2c}$.

$B_{2c}$.

Using these results and the equations of appendix B, and considering the major radius of the magnetic axis to be ![]() $R_0$, the first few terms in the expansion of

$R_0$, the first few terms in the expansion of ![]() $\sqrt {g}$ are

$\sqrt {g}$ are ![]() $g_0=s_G s_\psi R_0$,

$g_0=s_G s_\psi R_0$, ![]() $g_{1s}=0$,

$g_{1s}=0$, ![]() $g_{1c}=-2 s_G s_\psi \bar {\eta } R_0$,

$g_{1c}=-2 s_G s_\psi \bar {\eta } R_0$,

![]() $g_{2s}=0$ and

$g_{2s}=0$ and ![]() $g_{2c} \approx -2 g_{20}$, where (4.15) has been applied. The largest terms in (4.9) and (4.10) are then

$g_{2c} \approx -2 g_{20}$, where (4.15) has been applied. The largest terms in (4.9) and (4.10) are then ![]() $K_0 \approx 8 g_0 g_{2c}^2$ and

$K_0 \approx 8 g_0 g_{2c}^2$ and ![]() $K_{4c} \approx -K_0$, so

$K_{4c} \approx -K_0$, so ![]() $K_0 (1 - \cos 4\vartheta ) = 0$, implying

$K_0 (1 - \cos 4\vartheta ) = 0$, implying ![]() $\vartheta = j {\rm \pi} / 2$ for integers

$\vartheta = j {\rm \pi} / 2$ for integers ![]() $j$. The solutions for odd

$j$. The solutions for odd ![]() $j$ do not yield real solutions for

$j$ do not yield real solutions for ![]() $r$. For the even-

$r$. For the even-![]() $j$ solutions,

$j$ solutions, ![]() $\partial \sqrt {g}/ \partial \vartheta =0$ is satisfied automatically. The

$\partial \sqrt {g}/ \partial \vartheta =0$ is satisfied automatically. The ![]() $\vartheta ={\rm \pi}$ solution is just the

$\vartheta ={\rm \pi}$ solution is just the ![]() $\vartheta =0$ solution with

$\vartheta =0$ solution with ![]() $r_c \to -r_c$, so it is sufficient to consider

$r_c \to -r_c$, so it is sufficient to consider ![]() $\vartheta =0$. Solving

$\vartheta =0$. Solving ![]() $0=\sqrt {g}\propto g_0 + r_c g_{1c} + r_c^2(g_{20} + g_{2c})$ for

$0=\sqrt {g}\propto g_0 + r_c g_{1c} + r_c^2(g_{20} + g_{2c})$ for ![]() $r_c$ then gives the positive solution to be

$r_c$ then gives the positive solution to be

where the last equality follows from (B 1). If all terms through ![]() $g_4$ are retained in

$g_4$ are retained in ![]() $\sqrt {g}$ instead of just terms through

$\sqrt {g}$ instead of just terms through ![]() $g_2$, a root of

$g_2$, a root of ![]() $\sqrt {g}=0$ and

$\sqrt {g}=0$ and ![]() $\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta$ exists at

$\partial \sqrt {g}/\partial \vartheta$ exists at ![]() $\vartheta =0$ which is identical to (4.19) to leading order in

$\vartheta =0$ which is identical to (4.19) to leading order in ![]() $I_2^2 / |\mu _0 p_2| \ll 1$. Therefore the truncation at

$I_2^2 / |\mu _0 p_2| \ll 1$. Therefore the truncation at ![]() $g_2$ used for the robust solution is a good approximation.

$g_2$ used for the robust solution is a good approximation.

The plasma minor radius ![]() $a$ must be within the singularity:

$a$ must be within the singularity: ![]() $a < r_c$. This inequality can be written using (4.19) in the form of a

$a < r_c$. This inequality can be written using (4.19) in the form of a ![]() $\beta$-limit as follows:

$\beta$-limit as follows:

where ![]() $\bar {p} = (2/a^2) \int _0^a pr\,dr = p_0/2$ is an average pressure and

$\bar {p} = (2/a^2) \int _0^a pr\,dr = p_0/2$ is an average pressure and

is a coefficient of order unity that depends on the elongation ![]() $\kappa _e$. As discussed in appendix B,

$\kappa _e$. As discussed in appendix B, ![]() $\kappa _e= |Y_1(\vartheta ={\rm \pi} /2) / X_1(\vartheta =0)| = |Y_{1s}/X_{1c}| = 1/(\bar {\eta }^2 R_0^2)$. For surfaces with circular cross-section,

$\kappa _e= |Y_1(\vartheta ={\rm \pi} /2) / X_1(\vartheta =0)| = |Y_{1s}/X_{1c}| = 1/(\bar {\eta }^2 R_0^2)$. For surfaces with circular cross-section, ![]() $E\to 1$.

$E\to 1$.

For comparison, the tokamak equilibrium beta limit can be found in (236) of Mukhovatov & Shafranov (Reference Mukhovatov and Shafranov1971) or § 6.5 of Freidberg (Reference Freidberg2014). These previous results can be expressed as

where ![]() $\left \langle \right \rangle$ represents an average over the plasma and

$\left \langle \right \rangle$ represents an average over the plasma and ![]() $\iota$ is a characteristic rotational transform. The correspondence between (4.20) and (4.22) is apparent. An exact match of the coefficient (4.21) to earlier results like Freidberg (Reference Freidberg2014) is complicated because the earlier calculations include radially varying elongation and magnetic shear, which do not appear until higher orders in the Garren–Boozer expansion than the order we consider. The boundary separatrix in the earlier tokamak calculations cannot truly be represented by the shape (2.6) and (2.9) through

$\iota$ is a characteristic rotational transform. The correspondence between (4.20) and (4.22) is apparent. An exact match of the coefficient (4.21) to earlier results like Freidberg (Reference Freidberg2014) is complicated because the earlier calculations include radially varying elongation and magnetic shear, which do not appear until higher orders in the Garren–Boozer expansion than the order we consider. The boundary separatrix in the earlier tokamak calculations cannot truly be represented by the shape (2.6) and (2.9) through ![]() $O(r^2)$ used here, so we would not necessarily expect the numerical coefficient to match exactly. Nevertheless the basic scaling

$O(r^2)$ used here, so we would not necessarily expect the numerical coefficient to match exactly. Nevertheless the basic scaling ![]() $\beta \sim \iota ^2 a/R$ is in clear agreement.

$\beta \sim \iota ^2 a/R$ is in clear agreement.

Based on this successful comparison, the singularity calculation in §§ 4.1 and 4.2 could perhaps be used to find stellarator configurations with a suitably high equilibrium beta limit, as follows. Given a desired on-axis pressure ![]() $p_0$ and desired minor radius

$p_0$ and desired minor radius ![]() $a$,

$a$, ![]() $p_2$ could be set equal to

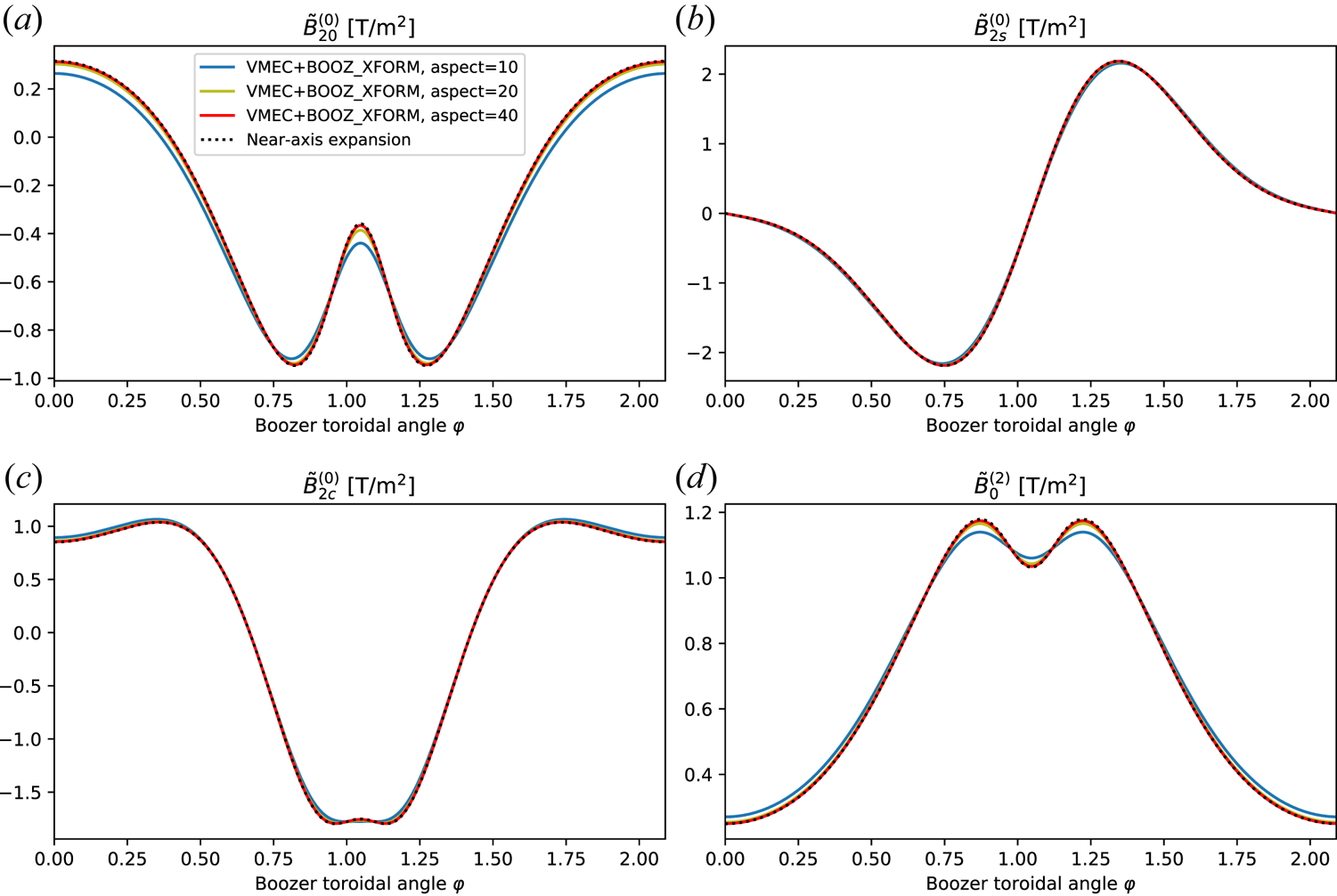

$p_2$ could be set equal to ![]() $-p_0/a^2$. Then other parameters of the Garren–Boozer model (axis shape,