Introduction

In their important work on the allocation of political attention, Jones and Baumgartner (Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005) explain that the political environment is especially information-rich and that political actors are faced with the challenge of issue prioritization. They say: “…prioritization somehow means winnowing – dropping from consideration for the time being problems that can wait” (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, 11). In a similar fashion, Kingdon described an “agenda” as the inventory of subjects and problems that receive serious attention from political actors (Reference Kingdon1984, 3; see also Cobb and Elder Reference Cobb and Elder1983). As a result of a “bottleneck of attention,” which implies that “only one or a very few things can be attended to simultaneously” (Simon Reference Simon1985), priorities need to be set.

Recent work has highlighted the importance of just such prioritization processes within political parties and bureaucracies (Gilad Reference Gilad2015; Öberg et al. Reference Öberg, Lundin and Thelander2015; Froio et al. Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2016; Baekgaard et al. Reference Baekgaard, Mortensen and Bech Seeberg2018; Bark and Bell Reference Bark and Bell2019). In this article, we provide an important contribution to this literature by examining this process of issue prioritization among a specific category of political organizations, namely, interest groups. Specifically, we ask what explains variation in the relative strength of different internal and external drivers as groups decide which set of policy issues to prioritise. As argued by Bauer in his study of agenda-setting in the USA. Senate: “the most important part of the legislative decision process was the decision about which decision to consider.” The representative’s major problem was “not how to vote, but what to do with his time, how to allocate his resources, and where to put his energy” (1963, 405; cited in Walker Reference Walker1977). Interest groups face a very similar challenge. We assume that set against all the possible issues a group might be considered to have a policy interest in, a group needs to settle on a sub-set of those matters to work on. By “policy work,” we do not refer narrowly to only active lobbying, but to the full range of policy preparation activities that groups engage in (see Jordan Reference Jordan, Flinders, Gamble, Hay and Kenny2009; Leech Reference Leech, Berry and Maisel2011).

While recognised as important, the process of issue prioritization within groups remains opaque. Previous work on this theme conceptualised and empirically assessed five possible drivers of issue prioritization: internal responsiveness, policy capacity, niche seeking, political opportunity structure (POS) and issue salience (Halpin et al. Reference Halpin, Fraussen and Nownes2018). The study indicated that most groups view each of these considerations as relevant to the prioritization process, hence the characterization of issue prioritization as a “balancing act.” What remains to be resolved, however, is what factors might explain variation in the relative importance of these distinct drivers at the individual group level. The previous study did not assess to what extent specific organizational features might affect the (relative) strength of a particular driver. For instance, to what extent are there systematic differences in the issue prioritization process between more generalist or specialist groups, and what are the possible implications of enjoying government access or facing strong competition for financial resources? While these key organizational features are often linked to lobbying strategies in the literature (e.g. Dur and Mateo Reference Dur and Mateo2013; Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2014), they have not yet been related to how groups might make trade-offs between different drivers of internal agenda setting. In this present article, we address some of these important questions and provide more insight into this balancing exercise, in particular focusing on why some groups put relatively more emphasis on particular internal or external drivers of issue prioritization. In this way, our work also speaks to the larger literature that argues a combination of internal (organizational) and external (environmental) factors shape the organization and behaviour of interest groups (Schmitter and Streeck Reference Schmitter and Streeck1999; Lowery Reference Lowery2007; Grote et al. Reference Grote, Lang and Schneider2008; Berkhout Reference Berkhout2013).

This article sets out to examine what considerations structure interest groups’ choices over what policy issues to work on. We integrate data from a survey of national interest groups in Australia with findings from a set of interviews with a cross section of 17 high-profile national interest groups. We define interest groups as formal organizations that are collective in nature (they have members/affiliates/a constituency) and are substantially engaged in public policy (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Halpin and Maloney2004). This means that we do not include institutions (such as companies or public entities) in our study. The next two sections clarify our theoretical framework and research design in more detail. In the analysis, we rely on our survey and interview data to explain possible variations in this process and to provide more specific insights into how groups approach issue prioritization. Our regression analysis indicates that differences related to the policy orientation and insider status of the group, its democratic character, and the extent to which it faces competition for membership contributions lead some groups to weigh particular considerations more heavily than others. While the literature often suggests that groups face difficult choices between internal responsiveness to members and capitalizing upon beneficial external political opportunities, both our interview and survey results suggest that groups consider these considerations largely compatible, even though they might put more emphasis on some considerations than others.

What considerations explain issue prioritization?

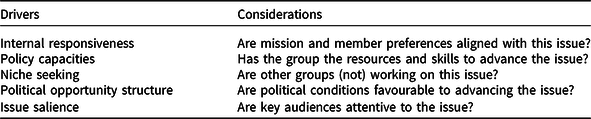

The “strategic concerns” that drive issue prioritization have not garnered sustained attention from interest group scholars (but see Hall Reference Hall2019 and Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007 for important exceptions). Recent research identified five considerations that shape the policy issue prioritization of interest groups: internal responsiveness, policy capacities, niche dynamics, political opportunity structures and issue salience (Halpin et al. Reference Halpin, Fraussen and Nownes2018; see Table 1 (adjusted) for a summary). Before formulating our main expectations, we briefly clarify these drivers.

Table 1. Summary of issue prioritization concept

Adapted from Halpin et al. (Reference Halpin, Fraussen and Nownes2018).

Several internal organizational considerations are likely to shape the issue priorities that groups establish. Internal responsiveness taps the notion that groups focus their attention on policy issues that align with the interests of their core constituency, or that are in line with their group’s mission (Truman Reference Truman1951; Minkoff and Powell Reference Minkoff, Powell, Powell and Steinberg2006; Halpin and Daugbjerg Reference Halpin and Daugbjerg2015). Given the variety in the internal organization and democratic nature of groups, this internal responsiveness can take different forms and relate to multiple and distinct internal stakeholders (such as members, supporters or donors). Policy capacity refers to the financial and human resources a group has at its disposal, including staff experience and expertise (Moe Reference Moe1980; Halpin and Binderkrantz Reference Halpin and Binderkrantz2011). If a group has previously worked on a given topic or has internal policy committees dedicated to this policy area, it is likely to pay continued attention to this matter (e.g. Hall Reference Hall2019, 339). This is so less for topics that are new to the organization, or on which there is limited in-house expertise. The niche-seeking dimension highlights how groups respond to other groups in their environment. On the one hand, they might seek out policy niches in which to specialise, to stress their unique nature, especially in a competitive environment (Browne Reference Browne1990; Gray and Lowery Reference Gray and Lowery1996; Heaney Reference Heaney2004). This applies to both more specialist and generalist groups. For instance, groups with a broad policy focus (for instance, environmental issues) will still aim to focus on a distinct sub-set of policy issues, to distinguish themselves from other groups that also have a more generalist orientation. On the other hand, groups might opt to join the bandwagon and focus their efforts on the issues that are already getting a lot of attention from other groups (Baumgartner and Leech Reference Baumgartner and Leech2001; see also Scott Reference Scott2013; Beyers and Braun Reference Beyers and Braun2014).

The external policy context characterizing a particular issue is also likely to play an important role. As underlined by Strolovitch, due to “reasonable desires for policy success” and “reputational advantages,” “organizations are likely to prefer high-profile, politically salient and winnable issues over more low-profile issues or issues that might not result in victories (Freeman Reference Freeman1975; McAdam Reference McAdam1982; Costain Reference Costain1992; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Tarrow Reference Tarrow, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996)” (2007, 21). As regards the political opportunity structure, both favourable and unfavourable conditions could be important triggers to take political action (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Austen-Smith and Wright Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994; Kollman Reference Kollman1998). While the likelihood of a policy win and the presence of government allies are likely to encourage lobbying activities (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009), a group might also need to counteract policy developments that go against their preferences. In that case, they may lobby for the status quo by engaging in “negative lobbying” through questioning the feasibility and the effectiveness of the formulated policy proposal (McKay Reference McKay2012; see also Varone et al. Reference Varone, Ingold and Jourdain2016). Finally, issue-specific features, salience in particular, are known to strongly shape lobbying behaviour (see Smith Reference Smith2000; Dur and De Bièvre Reference Dur and De Bièvre2007; Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014; Hanegraaff and Berkhout Reference Hanegraaff and Berkhout2018; Hall Reference Hall2019) and are, therefore, likely to co-determine prioritization processes. Attention from political or media elites (e.g. Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Larsen-Price, Leech and Rutledge2011; Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2014), recent (focusing) events (Cobb and Elder Reference Cobb and Elder1983; Birkland Reference Birkland1998) or popularity among the general public (e.g. Flöthe and Rasmussen Reference Flöthe and Rasmussen2019), can convince groups to push an issue up their agenda.

While previous research points to issue prioritization as a balancing exercise where all drivers are generally viewed as relevant considerations, there is some variation in the relative strength of these drivers for particular groups. We formulate four hypotheses related to several organizational features that have been demonstrated in the literature to shape other important group outcomes, such as lobbying strategies as well as variation in the level of access to policymakers that groups enjoy. Specifically, we formulate expectations related to the policy orientation of a group (its generalist or specialist nature), its access to policymakers, the extent to which it experiences competition for resources and the level of member involvement. In addition, our analyses will also include two standard control variables: resources and group type.

First, we expect generalist groups – that is, groups with relatively broad policy agendas that focus on multiple policy domains – to be more responsive to external factors (such as salience and POS), compared to specialist organizations that concentrate their policy engagement in one or two policy domains. We expect this because a generalist group by definition has a broad range of issues that it may choose to work on, and as such will probably choose issues where it has an advantage – issues, for example, on which it has allies in government or a high probability of winning (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Kimball and Leech2009; Halpin and Binderkrantz Reference Halpin and Binderkrantz2011; Lowery et al. Reference Lowery, Gray, Kirkland and Harden2012; LaPira et al. Reference LaPira, Thomas and Baumgartner2014). This aligns with observations from Lowery et al. who argue that, in dense interest group systems, “generalists will restrict their lobbying activities to those issues on which they have a comparative advantage – those addressing the broadest scope of interests to potential members” (Reference Lowery, Gray, Kirkland and Harden2012, 22). A specialist group typically focuses upon only one or a handful of issues and, thus, has less discretion in adjusting its policy agenda in response to changing external circumstances or particular societal events.

A similar logic could apply to the possible effects of enjoying access to policymakers, or in other words, being a “policy insider” (Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994; Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Beyers and Donas2015). Schmitter and Streeck famously argued that as groups engage more frequently with policymakers, they are likely to become more attentive to external factors like the government agenda, and at risk of being less sensitive to membership concerns (Reference Schmitter and Streeck1999). We assume that organizations will exploit whatever advantages they have in the policy process. If an organization has good access to, for example, a specific committee in the legislature, we expect the organization to be on the lookout for opportunities to exploit this access for its own gain and, therefore, focus on those issues that are high on the agenda of this particular committee, or topics that relate to the policy focus of this committee. To do this, however, the group must constantly monitor the political world to see precisely what its allies (and opponents) in government are doing (Gray et al. Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and Anderson2005; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Larsen-Price, Leech and Rutledge2011; see also Schrama Reference Schrama2019, 124). In addition, groups who enjoy access and have a strong public profile are keen to maintain this status and, therefore, face strong incentives to respond positively to demands from government for policy input on a variety of topics, or requests from journalist to provide their view on societal events (Fraussen Reference Fraussen2014, 415). Considerations about the political opportunity structure, and the salient nature of particular issues, are, therefore, expected to be weighted more strongly by groups who are policy insiders.

Third, we develop expectations about how funding may shape issue prioritization decisions. Much work has highlighted how (critical) resource dependencies such as different types of funding shape advocacy behaviour (e.g. Beyers and Kerremans Reference Beyers and Kerremans2007; Neumayr et al. Reference Neumayr, Schneider and Meyer2015; Chewinski and Corrigall–Brown Reference Chewinski and Corrigall–Brown2019; De Bruycker et al. Reference De Bruycker, Berkhout and Hanegraaff2019; see Braun Reference Braun, Lowery, Halpin and Gray2015 for a more detailed discussion). If we focus our attention on resource dependencies of a financial nature, it is reasonable to expect that a group facing strong competition from other like-groups for donors and members will be more sensitive to the wishes of its members and donors. We also expect that groups facing competition for government funding will be more attuned to what the government is doing (and the current political agenda) compared to groups that do not face such competition for government subsidies. More generally, we concur with Mosley who argues that groups will aim to “ensure alignment between the policy/funding environment and organizational priorities” (Reference Mosley2012). Specifically, she finds that as government funding increases, “organizations engage in policy advocacy primarily to promote and extend the existing policy priorities that their funding is based on” (Mosley Reference Mosley2012, 843). This dynamic might be reinforced by implicit or explicit grant conditions, as “governments may steer the focus of organised interests by granting funding tied to specific policy priorities” (Heylen and Willems Reference Heylen and Willems2018, 16). These expectations are likely to be highly nation-specific. An alternative expectation is that reliance on government funding, especially in regulatory regimes – like Australia – that preclude political comment when contracted by the government, will effectively silence groups from advocacy activities (see Maddison et al. Reference Maddison, Dennis and Hamilton2004). As only a small proportion of the groups included in our study relies on government funding – as we preclude groups for which service delivery is a primary function – our analysis will focus on the possible effects of competition for membership funding.

Our fourth expectation is that groups that offer high levels of member involvement will weigh the desires of their members more heavily, compared to groups that are characterised by a more passive membership, or dominated by professional staff (Jordan and Maloney Reference Jordan and Maloney1997; Skocpol Reference Skocpol2003; Albareda Reference Albareda2018; see also Binderkrantz Reference Binderkrantz2009 for a discussion). We would expect that the strength of the membership vis-à-vis the leadership of a group will matter for the policy agenda a group establishes. Thus, if a group has adopted mechanisms for member involvement such as regular meetings or policy committees, and outlets for member input into organizational decisions (such as periodic surveys, or the ability to vote on key decisions related to policy positions, or the structure and leadership of the organization), then that provides a key channel for members to communicate their preferences and hold the group leadership accountable (Halpin and Fraussen Reference Halpin and Fraussen2017). In such cases, we expect internal responsiveness to be a strong consideration. In contrast, if the involvement of members is limited, a group is likely to be less attentive to the concerns of its constituency (Kröger Reference Kröger2018, 9–10).

Below, we present an overview of our main hypotheses.

H1: More generalist groups attach more importance to external factors than more specialist groups.

H2: Groups with government access attach more importance to external factors than groups with no government access.

H3: Groups that face competition for financial contributions from members attach more importance to internal factors.

H4: Groups that offer high membership involvement attach more importance to internal factors.

Research design

The research team undertook an online survey of national interest groups in Australia during September–November 2015. The survey population was drawn from a list of national organizations compiled by the authors. The list started with the 2012 edition of Directory of Australian Associations; we limited our focus to national organizations and excluded associations that are not politically active or do not have members. Footnote 1 This process resulted in a population of 1,353 interest groups (for more details, see Fraussen and Halpin Reference Fraussen and Halpin2016). In total, 370 organizations (for a response rate of 27%) completed our survey. This is comparable to that of other national surveys of this type in recent years (Marchetti Reference Marchetti2015). The distribution of group types who responded to our survey is very similar to the organizational diversity in our population, giving us some confidence about generalizing to our broader population.

Dependent variables: five drivers of issue prioritization

To assess the importance of different considerations that could shape issue prioritization, we include a question consisting of a range of items that groups might consider relevant. Specifically, we asked groups to what extent they agreed (measured on a five-point scale) that each item was an important consideration when prioritizing a policy issue. To avoid order effects, the presentation of these items was randomised. The specific wording of the question was as follows: “Regardless of its general policy interests (e.g. the environment, health, trade and education), an organization must choose which specific set of issues to prioritise at any given time. For each factor listed below, please indicate your level of agreement.” An overview of the different items associated with each driver is presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Issue prioritization: dimensions and individual items

+ The term “government” refers to the executive, e.g. in the Australian case the Cabinet.

Note: The n varies between 350 and 356 for all items, except for questions “e” (institutional contributors; n = 173) and “f” (large donor contributors; n = 286), as groups were asked to skip these survey items if they were not applicable to them. Subsequent analysis in this article drops these two items.

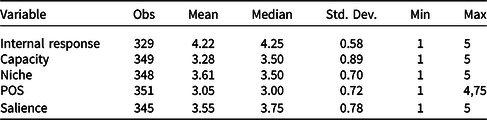

To operationalise the five drivers of issue prioritization, we constructed scales by calculating the mean scores across the survey items (measured on a five-point scale) that correspond to our five concepts. Consistent with the labelling in previous work, we call the scales: (1) Internal responsiveness; (2) POS; (3) Salience scale; (4) Niche and (5) Capacity. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to establish that the developed survey items form a set of latent variables that matched the hypothesised structure. That work established that the theoretically generated model of issue prioritization – constituting five distinctive drivers identified above – can be detected empirically (see Table A1 in Appendix for an overview of the scores on individual survey items and Figure A1 in Appendix for details on the CFA). Table 3 reports summary statistics for the constructed scales.

Table 3. Summary statistics: dependent variables

Independent and control variables

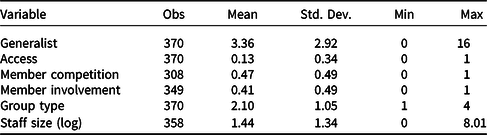

In the analyses that follow, we focus on the possible impact of four factors on the strength of each of the five drivers of issue prioritization: a group’s generalist or specialist policy orientation, its access to policymakers, competition for membership funding, and the involvement of members. Furthermore, we also control for group type and resources. We clarify our operationalization of the variables related to these factors in the following paragraphs and report summary statistics in Table 4 at the end of this section.

Table 4. Summary statistics: independent variables

Our first set of variables focuses on the policy activity of groups. Generalist captures the number of policy domains that a group reports to be active in, and as such indicates its “breadth of policy engagement” (Halpin and Binderkrantz Reference Halpin and Binderkrantz2011, 202). We asked groups the question “Please indicate the policy domain(s) in which your organization is active?” providing a list of 21 policy domains. In our analysis, we take the raw count of domains that each group indicated they were active in.

We also expect that groups who have more standing with policymakers will likewise vary in respect of weighing the different drivers of prioritization. To assess the possible effects of access to policymakers, the variable Access measures whether a group has been invited to give oral evidence to an Australian Senate committee during a 4.5-year period spanning 28 September 2010 to 10 March 2015. As a dummy, we distinguish groups with no access (i.e. no oral evidence; 0) from those enjoying at least occasional access to policymakers (i.e. one or more oral submissions; 1). Of the groups included in our sample, 13% (n = 48) can be considered policy insiders. We operationalise this as a dummy as we aim to assess the effects of a group having access or not, consistent with similar binary approaches in the literature (see Maloney et al. Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994; Binderkrantz et al. Reference Binderkrantz2006; Albareda and Braun Reference Albareda and Braun2019). Variation in funding is also likely to shape the role of different prioritization drivers. Here, we specifically focus on the extent to which groups experience competition for their different funding sources. We asked groups “Please indicate to what extent you face competition from other advocacy groups in gathering these resources,” providing categories for government, donor and members funding and with following response options: none, a little, moderate or a lot. Whereas 83% of the groups included in our survey rely on membership contributions, only 28% of the groups receive government funding, and 23% rely on donations. To assess the possible effects of competition for funding, we focus on the income source that is relevant to most of the groups, namely, competition for member funding. We have recoded this variable, considering groups who responded “moderate” or “a lot” as groups that experience meaningful competition.Footnote 2 The variable Members is a dummy to indicate competition over member funding (0 = no, 1 = yes).

To assess the participatory nature of the group, we generate the variable Member involvement, which is a self-reported measure of how active a group’s members are. Specifically, we use the responses to the survey question, “Organizations vary in the degree to which members or supporters are involved and active (i.e. express opinions, contact organizational leaders, attend organizational functions, etc.). How about your organization’s members or supporters?” The answer options included “not too involved,” “somewhat involved” and “very involved.” In our analysis, we focus on the distinction between groups with high and low level of member involvement. For this reason, we distinguish between groups who indicated that their members were “very involved” (=1), and those that reported their members were “somewhat” or “not too” involved.Footnote 3

Finally, there is a very strong research thread highlighting group type as a pivotal factor in many facets of group behaviour. Here, we distinguish among four types of groups and create four corresponding dummy variables called Citizen group, Business group, Professional group and Service group, the latter referring to interest groups that combine advocacy with the provision of services (e.g. social service providers who also lobby on behalf of “client” groups they serve). In the analysis, we present Business groups as the reference category. Overall resource levels are also likely to shape the importance of different issue prioritization drivers. We tap this by reference to the number of staff, which is frequently used in the literature as a proxy for financial resources. The variable Staff size is a self-reported measure of how large a group’s professional staff is. We take the natural log given the non-normal distribution of this variable.

The survey data enable a systematic assessment of our expectations. To provide a better insight into the possible relationships among the different drivers of issue prioritization, we undertook a set of qualitative interviews to illustrate these mechanisms from the perspective of those at the helm of groups. The data result from a set of semi-structured interviews with a cross section of 17 high profile national Australian interest groups, conducted between November 2016 and late 2017 (see Table A2 in Appendix for an overview). The research team identified all groups that were among the 100 most visible actors in the Australian group system (taking into account their presence in different political arenas, such as the parliament and the media). We then selected groups from each of the main group types (business groups, citizen groups, professional, and service groups) to ensure that we had sufficient variation. In total, 20 groups were contacted, of which 17 responded positively to our interview request. Each interview lasted around 1 hour and was conducted by one (or two) of the authors in person. One-third of the interview script covered the themes of issue prioritization and internal agenda setting.

Analysis

The literature is well versed in the notion that groups will apportion their finite attention in different ways (Baumgartner and Leech Reference Baumgartner and Leech1998; Halpin and Binderkrantz Reference Halpin and Binderkrantz2011). We know groups need to limit and prioritise their attention to a limited set of policy issues, but we have little insight into this particular process.

We can learn more about the nature of the issue prioritization process by examining the correlations between the five different drivers. As Table 5 shows, all drivers are positively correlated with one another, though the coefficients are generally low (all below the 0.3 level). Again, this supports the notion that there is no intrinsic incompatibility in groups weighing any one of these drivers alongside one another when prioritizing issues (and it re-confirms their distinct nature, as we do not find a high correlation between drivers that theoretically could be closely related, such as POS and Salience).

Table 5. Correlations between the different drivers of issue prioritization

Kendall’s Tau-b; *p < 0.05.

Subsequently, we assess our hypotheses to examine whether particular organizational features result in a (relatively) stronger prioritization of certain drivers, such as internal responsiveness or salience. We do this by estimating five equations to test a limited set of hypotheses. An ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation of these models may be problematic, given the already noted connected nature of our dependent variables. Moreover, our hypotheses are somewhat intertwined. Therefore, we estimate seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) models. As discussed by Zellner (Reference Zellner1962), this approach consists of a set of linear regression equations that contemporaneously deal with cross equation error correlation. The SUR technique addresses this cross correlation of errors. Table 5 demonstrated that our drivers are positively correlated, yet at relatively low levels. Nevertheless, the results of the Bruesch-Pagan test of independence lead us to reject the null hypothesis, concluding that these concepts are not independent. Footnote 4 Table 6 reports the results of our regression models. In what follows, we will discuss key findings related to the five distinct drivers following the order of the five models, which enables us to provide an in-depth discussion and facilitates the integration of our quantitative and qualitative empirical evidence.

Table 6. SUR with issue prioritization measures as dependent variables

Notes: Numbers are coefficient estimates, standard errors are in parentheses.

***p < 0.01 (two-tailed test), **p < 0.05 (two-tailed test), *p < 0.10 (one-tailed test).

Our first model sets out to explain variation in the role that internal responsiveness plays in issue prioritization processes. We hypothesised that groups with higher member involvement would attach relatively more emphasis on internal factors (H4). The results show that groups reporting high levels of member involvement (those who indicate their members are “very” involved) do consider internal responsiveness as more important in their prioritization processes compared to groups indicating that their members are “not too” or “somewhat” involved. It would appear that where groups commit to high levels of member involvement, they tend then to be more attentive than other groups in weighing membership wishes and their mission when deciding which issues to prioritise.

Furthermore, in addition to the significant positive effect of resources, we find that generalist groups are more likely to emphasise internal responsiveness as an important consideration. This finding was unexpected, as we anticipated that groups with a broader policy agenda would be more sensitive to external considerations. Yet, as we clarify below, more generalist groups do also appear more attentive to considerations related to salience. Hence, while they might opportunistically shift from one policy issue to another (as the political salience of an issue evolves), they do not appear to disregard the preferences of members and other internal stakeholders and, hence, somehow manage to balance these different internal and external considerations.

As clarified by one professional group with insider status:

Now from year to year, we will determine our priorities based on the aspirations of our executives and directors, but also we are necessarily a reactive organisation in a significant part, because a substantial amount of our work is driven by the Federal Parliamentary agenda, so when issues come up on the Federal Parliamentary agenda that enliven any concerns that align with our policy commitments, we will engage with those issues and promote the [Group name] interest. (ID6)

With the exception of staff, none of our variables appears to have a significant effect on the importance of the capacity driver (model 2). In contrast, several organizational features seem to explain variations in the role of niche seeking in issue prioritization. Our third model shows that group type is somewhat important with respect to explaining variations in the role of niche considerations. The results show that (in particular) professional groups and citizen groups are significantly more likely to agree that niche considerations matter in issue prioritization, as compared to our reference category (which is business groups). These findings are unexpected and suggest that these two group “families” are more attuned to the population dynamics within their fields when deciding what issues to dedicate their attention to, compared to other group types.

We also find a positive association between institutionalised access and agreement that niche considerations matter in issue prioritization decisions. Furthermore, as hypothesised, we find that competition for members is positively associated with weighing niche considerations (H3). One interpretation of these findings is that the behaviour of groups is at least partly determined by the strength of competition with other groups, which can involve competition for gaining access to policymakers (leading to either specialization in a unique policy niche, or joining policy bandwagons) and/or competition for membership subscriptions. This result is broadly consistent with the argument put forward in the well-developed population ecology literature, whereby partitioning of policy space – tapped by our niche driver – is shaped by considerations over support from a groups’ potential constituency (Gray and Lowery Reference Gray and Lowery1996; Halpin and Jordan Reference Halpin and Jordan2009). We hypothesised that insider groups would be more sensitive to external factors, such as the political opportunity structure and salience (H2), as their close ties with policymakers make them more attentive to the government agenda (compared to being responsive to membership demands) (Schmitter and Streeck Reference Schmitter and Streeck1999). Yet this expectation is only confirmed for the political opportunity structure (see model 4).

This sensitivity to both internal and external factors, in particular for groups that have a broad policy agenda (responsiveness and salience) or are policy insiders (niche and POS), resonates with our interview findings. Several of our interview respondents emphasised that the outcomes of issue prioritization are an interplay of multiple considerations. In addition to internal responsiveness, the decision to actually engage on a particular issue is also strongly shaped by how external events, such as the political opportunity structure, or the extent to which other groups are (not) working on this issue. The quote below from a generalist citizen group provides a clear illustration of this interplay:

The biggest one is breadth versus depth and that’s a constant struggle for us, because our mandate is so broad being an advocate for the interests for people on low incomes. It is everything from climate change to health policy to employment to housing to tax, obviously. We have tried to be a lot more disciplined in the last few years about intervening only where we can have a unique impact if there is an opportunity for impact or change, or there is no one else who is going to speak up on this issue in this way unless [GROUP NAME] does. (ID9)

Finally, the fifth model shows that policy generalists – groups that are active in multiple issue areas – are more likely to prioritise issues through weighing their salience. It is important to note that this driver incorporates various dimensions of salience (such as salience with government, public, and media agendas), which could be a reason that we observe no other significant effects (even though the salience of issues is generally considered an important predictor of lobbying behaviour). One possible explanation for the significant effect of being a generalist might be that these groups spend more time scanning the external environment for information about what issues to focus upon than do specialists. This makes sense in that narrow policy specialists may find that they are locked into responding to issues that fall into their narrow remit, while generalists have more room to “play in” or “winnow out” issues that are less likely to get political traction.Footnote 5 As stated by one of the generalist groups, we interviewed:

Now initially after [our annual] congress, it was clear that we were not going to get a lot of political support for that [issue]. And there was not a great deal of community interest in that. And then, the external environment started to change. So it went from being a lower priority to being a higher priority. So from our perspective there is … it is important to maintain some flexibility about what if you like… what is the priority of the day? Which is why we keep a very broad platform. (ID14)

A comparison across the five models reveals that different sets of variables explain variation in the emphasis placed on drivers of issue prioritization. The only variable that performs in a similar manner across more than two of our models is staff size (a proxy for a group’s financial resources), which has a positive significant effect on internal responsiveness, capacity, and salience. As this variable relates to both internal and external considerations, one interpretation is that the need to prioritise some policy issues over others might be less urgent for groups with a lot of financial resources (see also Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, McGee and Thomas2019, 7).

Conclusion and discussion

While there is a strong focus on the visible political activities of interest groups, such as media statements and testimony to legislative committees, these actions are the outcome of an intra-organizational process in which groups consider the issues they will prioritise in their political work. Building upon previous research highlighting that groups cannot attend to each issue in which they might conceivably have an interest (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Baumgartner and Leech Reference Baumgartner and Leech2001; Halpin Reference Halpin, Loomis and Nownes2015), we set out to explain the varied importance of different drivers for priority setting within groups, distinguishing internal responsiveness, policy capacities, niche seeking, political opportunity structure and salience.

Our interview findings suggest that it is not so much a matter of prioritizing one particular driver over another or making the trade-off between working on a key concern of the membership versus reacting to what is on the news or government agenda of the day. Rather, groups seem continuously focused on aligning (changes in) their external environment with internal priorities, the mission of the organization or its core policy expertise (even though they do not always succeed). The following quote captures this complexity well:

So, the primary four criteria that we pass any potential issue through are: Detriment; so is there evidence of harm? Sentiment; is there evidence that people care about it? Policy Opportunity; so can we actually make a difference over the next twelve months? And Organizational Opportunity; so is it aligned to other things that [GROUP Y] is doing given that policy and advocacy is not the only thing we do? And so, I guess what we look for, in a perfect world, is issues that tick all four of those boxes. Few do.

Usually, they might be compelling issues that tick two or three out of four, and then it becomes, I guess, a more qualitative trade-off. And look, in a sense the whole process is qualitative; you know there is no such thing as a mathematical formula to determine what you will advocate on, but at least it brings, I guess, a degree of rigour and hopefully some transparency to what we decide we are going to do. And then, all of that ultimately gets mapped against how many people we have got. So, sometimes something will drop off, even though it might have ticked a few boxes, just because we cannot do it. (ID3)

We also examined which organizational features might explain the varying importance of these different drivers of issue prioritization across groups. We find some evidence that elements related to the type of group, their policy orientation and the level of competition they experience for membership subscriptions and explain why some groups are more sensitive to particular internal or external drivers. Specifically, the policy orientation of the group, whether it is a policy insider or has a broad policy agenda, shapes issue prioritization processes, as does the level of member involvement and whether groups face a competitive funding environment. At the same time, these differences are not as clear-cut as the literature sometimes assumes. For instance, except for niche seeking, we find no systematic differences between different types of groups. Likewise, the financial resources of the group seem to positively affect several of these drivers, such as internal responsiveness, capacity, and salience.

These results have important implications for scholarly debates on how groups make strategic trade-offs and engage in policy processes. While the literature tends to anticipate intra-organizational decisionmaking to be complex and multi-dimensional, scholars often adopt convenient frames which juxtapose, for instance, political opportunity and salience with internal responsiveness. The results here suggest that there is nothing inherently incompatible with our five drivers of prioritization. All drivers that we measure are positively correlated with one another, suggesting group leaders are able to – or, at least attempt to – weigh them up together. Hence, our findings suggest it would seem unhelpful to consider groups as either intrinsically member orientated or externally focused on the political environment. This message fits well with research finding that groups will balance the imperatives of lobbying and policy influence with those of organizational maintenance and survival (Lowery Reference Lowery2007; Hanegraaff et al. Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016).

At the same time, the variables that do seem to explain the relative importance of each of our drivers are somewhat different, which means we cannot unequivocally say that each driver is operating entirely similarly. This leads us to conclude that while group leaders might have the abilities to balance different drivers, this does not imply that taking into account internal and external considerations is an easy task. In particular, it might be especially challenging for groups who are policy insiders and have a broad policy agenda.

It is important to keep in mind that we report a generalised orientation to issue prioritization at the group level. Whether groups find that they can balance all of these drivers for every issue, or whether they give precedence to one over the other on an issue-by-issue basis, is not something we can answer with the data we have assembled. Furthermore, our study relies on survey data from a representative set of national interest groups and interviews with 17 high-profile national groups. The reliance on self-reported items is a limitation of this article, yet one shared with similar approaches in other studies that survey groups on the use of particular lobbying strategies or their interactions with policymakers (see Binderkrantz Reference Binderkrantz2006; Dur and Matteo Reference Dur and Mateo2013; Weiler and Brandli Reference Weiler and Brändli2015; Hanegraaff et al. Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016).

Perhaps the most significant limitation is that our modelling strategy, unfortunately, ends up treating each priority separately. Yet the qualitative work we report shows that these considerations are not disconnected; in fact, quite the opposite. Future work might try to address this in a number of ways. Case studies that document and compare the specific policy agenda of a more limited number of (different types of) groups could further increase our understanding of these processes and enable the fine-tuning of the issue prioritization framework we have presented (see for instance Hall Reference Hall2019). Another promising avenue for future research involves more attention to how specific issue features might shape the prioritization process and the importance of different considerations. For instance, survey experiments could assess whether certain issue characteristics or external circumstances incentivise group leaders to give more weight to external factors rather than internal considerations and, in this way, provide more insight into the interconnected nature of these drivers and the trade-offs made by group leaders. We might imagine that some issues are so core to the mission or constituency of particular groups that they would have to prioritise them irrespective of prospects of success or favoutable external conditions.

Finally, our empirical analysis focuses on the single case of Australia. While we expect the specified drivers to be relevant for groups operating in a variety of democratic systems, there might be variation in their relative importance due to differences in group systems and political systems, in particular the openness of the political and media arena, as well as variation in group-party ties and alignment (see Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, McGee and Thomas2019). We hope this work provides a solid foundation for more research on the prioritization processes of interest groups and their policy agendas.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X2000015X

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ESBEU0

Acknowledgement

Halpin wishes to acknowledge support through an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (DP140104097: The organised interest system in Australian Public Policy). Earlier versions of this article were presented at the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference (2018), the American Politics Group seminar at the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill) and the Research Seminar of the Faculty of Governance & Global Affairs at Leiden University, and the authors are grateful for the many helpful comments made, some of which have been directly incorporated.